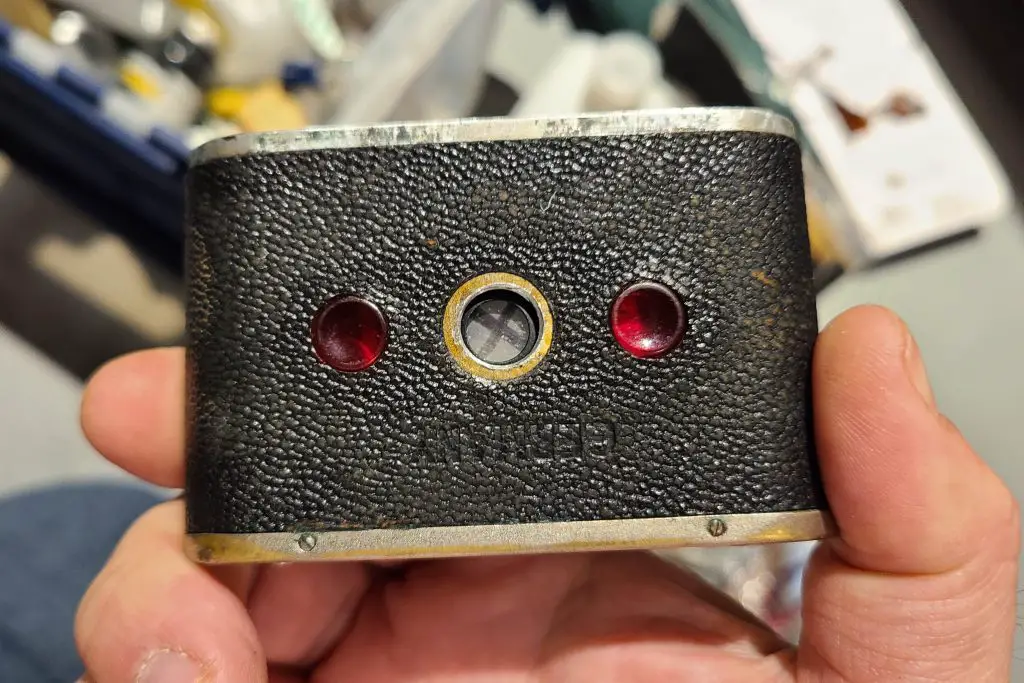

This is a Wirgin Gewirette, a compact camera produced by Wirgin in Wiesbaden, Germany starting in 1932. The Gewirette was one of the company’s earlier models and shot 3cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. Although lacking an interchangeable lens mount, the Gewirette was fitted with a large number of shutter and lens combinations from simple triplets, to top of the line 6-element Schneider Xenons. The Gewirette was a popular camera that was produced until about 1938 when after the company’s founders Heinrich and Josef Wirgin fled Germany to escape persecution, was relaunched by a state run company called Adox as the Adoxette. Two versions of the Gewirette were created, this the second version, had a solid optical viewfinder with an accessory shoe for use with a rangefinder or meter, and the original with no shoe and a flip up viewfinder.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (sixteen 3cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 5cm f/2.9 Steinheil München Cassar uncoated 3-elements

Focus: < 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Prontor II Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/175 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 307 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Wirgin Gewirette is a very compact and well built pre-war camera that shoots 3cm x 4cm images on 127 format roll film making it one of the smallest medium format cameras ever made. With it’s lens collapsed, the camera fits neatly into a medium pocket or small handbag. Shooting the camera is a slow process as it lacks any modern conveniences, but when used with patience, will reward you with sharp and very distinct looking images. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.2 | ||||||

History

Wirgin could very well be the most important camera company that western photographers have never heard of. While a great number of companies have come and gone from various countries, none had the history or the relevance of Wirgin.

Originally formed in 1920 by brothers Heinrich, Max and Josef Wirgin, like most early camera companies, Wirgin’s first products were accessories and other photographic goods used by amateur and professional photographers of the time. It is not clear if Wirgin sold these products under their own brand, or under a white label. My best guess would be that of a white label as I’ve never found any photographs of anything with a Wirgin name from the 1920s.

When exactly Wirgin produced their first camera is unclear. According to a German language site listing all of Wirgin models, in 1926 the first folding plate cameras were released. Most other sources online suggest Wirgin’s first cameras were simple box and rollfilm cameras from around 1930. Regardless of whichever is correct, we know that by the early 1930s, the Wirgin brothers were churning out a variety of inexpensive cameras, competing in an increasingly competitive German camera market.

Around 1932, the company would release a compact roll film camera called the Gewirette which used what was then referred to as “Vest Pocket” film, named after the Kodak Vest Pocket which was the first camera to use it. Vest Pocket film would later be known as type 127 film, but was one of the smallest roll film formats, with an overall width of just 46mm.

Cameras that used Vest Pocket film were usually very small, often employing some kind of folding or collapsible lens design. The Gewirette went with a solid body and collapsible lens design. When closed, the camera could easily fit into a small hand bag or medium coat pocket. It would end up being one of the smallest roll film cameras ever made, yet for it’s size made remarkably large 3cm x 4cm images that still captured a lot more detail than “kine” 35mm cameras like the Leitz Leica could.

Like most cameras of the day, the Gewirette was made available with a wide range of shutter and lens combinations. Less expensive models had simple Prontor shutters with Wirgin Gewir lenses, while others had higher end Meyer and Schneider lenses with Compur shutters.

Two distinct versions of the Gewirette were made, neither of which received an official model designation by Wirgin, but are referred to as v.1 and v.2 by collectors today. The two versions are easy to tell apart as the original has the viewfinder located in the center of the top plate, no accessory shoe, and no doors covering the rear red windows. The second version added the accessory shoe and red window doors, and switched moved the viewfinder off to the side to make room for the accessory shoe.

The 1930s German camera industry was very crowded with many models struggling to compete with so many similar models made by other companies, but one of Wirgin’s biggest strengths were their relationships with international distributors. Wirgin cameras were sold in the United States and United Kingdom. Name variants of the Gewirette exist such as the Wirgin Reporter and the Miniature Marvel.

When exported to the United States, the prices were typically modest with the lower end models more commonly found. The ad to the right from Central Camera’s 1938 catalog lists the Gewirette as selling for between $9.95 with a 2 inch f/4.5 anastigmat (probably a Wollensak) lens and $24.75 with a Meyer (probably Trioplan) f/2.9 lens and Compur shutter. These prices, when adjusted for inflation, compare to $195 and $480 today.

Wirgin produced the Gewirette up until 1938, when company founders Josef, Max, and Heinrich were forced to flee Germany to the United States to avoid anti-Jewish political turmoil occurring in Germany at the time.

Information online is not totally clear on what Wirgin’s exit plan was. Some say that Wirgin handed over their factory and patents over to another German firm called Fotowerke Dr. C. Schleussner GmbH, other stories cite that Wirgin was abandoned, and Schleussner simply took it over.

Whichever story is true, many of Wirgn’s cameras like the Gewirette and their 35mm Edinex continued production under the name brand Adox. Some Gewirette cameras were branded as the Adox Adoxette, but many weren’t labeled at all, sold with no names. The Adox produced versions were produced until 1939 or possibly early 1940, but did not continue past the war.

At a glance, it is not always easy to tell the difference between a Wirgin Gewirette and Adox Adoxette as not only do they look very similar, but white label versions of both cameras were made. Some Adox cameras will have the name “Adox” embossed into the rear leather, but not all of them do.

As best as I can tell, the distinct feature of the Adox cameras is that the two knobs on the camera’s top plate are identical, compared to the Wirgin’s where they differ. Wirgin cameras will have the letter “Z” engraved inside of the right knob, whereas Adox cameras have two Z’s engraved on the top plate.

By 1940, production of the Adoxette had stopped, and was not continued after the war. Around 1945, both Heinrich and Josef Wirgin, who were now using the names Henry and Joseph, returned to Germany to take back their company. Max Wirgin stayed in the United States where he founded the Camera Specialty Company, or Caspeco for short where he would import Wirgin and other German cameras like the Exakta.

In Germany, Wirgin would thrive, resuming it’s prewar Edinex cameras, and with the help of a German precision mechanic and camera designer named Heinz Waaske, would eventually release a successful line of Edixa 35mm SLRs.

Wirgin would remain successful through the 1950s and into the 1960s, eventually becoming Edixa GmbH in 1968, a name it would use for four more years before going out of business in 1972. Although neither the company, nor any of it’s products would reach the level of reverence as other German makers like Leitz, Zeiss, or Rollei, it hung in there for almost as long as those other companies, producing quality SLR, rangefinder, and motion picture cameras that are still desirable by collectors.

Today, many collectors have a soft spot for Wirgin cameras. Whether it is their 35mm Edixa SLRs or their less expensive models like the Gewirette. These were well built and compact cameras that are special because of

My Thoughts

One of the earliest cameras I ever reviewed was the Wirgin Edinex II which I wrote about in July 2015. Back then, I knew very little of the Wirgin company, or the vast number of cameras that had come out of Germany at that time. While researching that camera, I learned of an earlier, and smaller camera called the Gewirette. Enamored with the camera’s good looks and small size, I sought out to acquire one.

I wouldn’t know it then, but it would take over 5 years before one would show up in the collection. When it arrived, I expected it to be small as I had seen a number of images of ones before, but I was not prepared for how compact the camera was. Easily fitting into the palm of my average sized hands, the Gewirette is perhaps one of the smallest medium format cameras ever made. Despite making images that are physically larger than the 35mm Edinex, the Gewirette is quite a bit smaller than it’s sister camera.

The top plate is a bit misleading as it has two round knobs that suggest one is an advance and the other is rewind, but like most other roll film cameras, the film transports only in one direction via the knob on the left, marked with the letter “F”. Turn this knob in the direction of the arrow to advance the film.

The knob on the right with the letter “Z” however, is the film compartment release. When the letter Z on the knob is lined up with the Z on the top plate, the top plate is locked into position. Rotate the knob in the opposite direction of the arrow and the lock is released and you can lift up on the entire top plate to access the film compartment.

The only other things on the camera’s top plate are the viewfinder and accessory shoe which could be used for a clip on rangefinder or exposure meter.

With the top plate removed, the film compartment resembles other bottom loading cameras like the Kodak Vest Pocket in which you must pull out the take up spool and load a new roll of film outside of the camera, and then drop both into the camera, ensuring that the backing paper slides between the film gate and pressure plate. Unlike bottom loading 35mm cameras, there is no need to trim anything, but you must make sure the paper leader is securely attached to the take up spool and that nothing gets jammed while loading. It’s not difficult to do, but is definitely something you don’t want to rush either.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 3/8″ tripod socket and two small feet which really serve no purpose since I could never find a way to set the camera down on a flat surface without it tipping forward. The larger diameter tripod socket means you would not be able to mount this camera to a modern tripod without an adapter.

I am uncertain why Wirgin went with a top loading design, other than perhaps they found it easier to mount the locking knob on top, rather than the bottom.

The Gewirette has a collapsible lens, and lacks any safety device to prevent you from firing the shutter with the lens retracted, so be sure to use the two grips near the 3 and 9 o’clock positions around the lens to extend the lens before making any exposures, or else you’ll have a roll full of badly out of focus images.

When pulling the lens and shutter out, you’ll notice that the two grips are at a slight angle, but when the lens is fully extended, a slight counterclockwise twist will not only straighten them out, but also locks the shutter and lens into position, so that it cannot be accidentally closed while shooting.

The top of the shutter has a slider for selecting f/stops from f/2.9 to f/16, the cocking lever, and the shutter release. Next to the shutter release is a threaded hole for using a cable release. Focusing the lens is done by rotating the front lens group to align the engraved markings from just under 4 feet to infinity with the red painted tab. The minimum focus distance is not indicated as it goes quite a bit lower than 4 feet.

The back of the camera has two red windows, covered by a double hinged metal plate that protects light from entering either window. To see through the windows, you can either pull back on either side to reveal the window beneath, or rotate the entire thing out of the way to see both windows at once.

The Gewirette shoots “half frame” 3cm x 4cm images on 127 film which did not come with exposure numbers for this format. This means you need to use each exposure number on the film’s backing paper twice. With a fresh roll of film loaded, the first exposure is made when the number 1 shows in the right window. After exposing your image, advance the film until the number 1 shows in the left window and make another. Your third exposure is made with the number 2 in the right window, and your fourth with the number 2 in the left window. Keep doing until until you make sixteen exposures, at which time the number 8 will be in the left window. The Gewirette lacks any sort of double exposure prevention, so be sure to properly advance the film prior to making each new exposure.

The viewfinder is very simple with just two pieces of glass to approximate a 3×4 image. When looking through the window, part of the shutter is visible, blocking the bottom right corner of your image. Although it is small, I had no problem seeing through it, even while wearing prescription glasses. As was the case of all viewfinders like this, there is no information about exposure to be seen through the viewfinder, nor any attempt made to account for parallax.

The Gewirette is an immensely appealing camera even without using it. It’s pre-war nickel and leather German design is gorgeous, it’s compact size gives it a look that few other roll film cameras had, and with it’s larger than 35mm image size and good combinations of lenses and shutters, should be capable of quality images. But how is it to shoot?

Repairs

This Gewirette came to me in a lot of other cameras and had a stuck shutter that wouldn’t fire. Cleaning the shutter with generous amounts of naphtha is all that it needed, but upon reassembling the camera, I ran into a problem, as gaining access to the shutter requires removing the front lens grouping, and putting it back together requires me to confirm focus. I’m no stranger to collimating a lens as I’ve done it a number of times, but this requires gaining access to the film compartment to insert a piece of ground glass that I can focus on. Since the Gewirette is a top loader and does not allow you to see the film compartment from behind, I didn’t think I’d be able to do it, until I realized that I could simply unscrew the metal door that protects the red windows on the back of the camera and that would give me a nice round hole that would allow me to see straight through the camera.

In the gallery below, I show what I needed to do to adjust focus. With the top plate off, you can slide in your ground glass into the film plane, then with the rear door off, you can see right through to the film compartment. Pointing a digital camera with a relatively long lens directly at the Gewirette’s lens with both lenses set to infinity and the shutter open in Bulb mode, you should be able to see the markings on the ground glass perfectly in focus. If the image on the digital camera’s LCD screen is blurry, you need to rotate the Gewirette’s lens until the image is sharp, at which point, it is set to infinity.

With the shutter firing at all speeds, and the focus properly adjusted, it was time to use the camera.

My Results

For the first roll in the Gewirette in likely has been more than half a century, I chose film that was created half century before.

Back in 2019, I came across a lot of a 127 film called Supre-Tone which comes in an orange wrapper with the words “Made in Germany” in it, and nothing else. There is very little information online about this film, but to the best of what I could find, it was an ASA 50 speed panchromatic film made in the 1960s. I’ve shot this film a number of times in other 127 cameras and know that it is what I call a “time machine film” in that it doesn’t seem to age. The film shoots at box speed, shows no excessive signs of grain and without any interaction or bleed from the backing paper. It truly is a marvelous film and I will be very sad when I shoot my last roll of it. But for now, I use it sparingly on cameras like the Wirgin Gewirette to get an idea of what it might have been like to shoot when it was new.

As mentioned earlier, the Supre-Tone film shoots at ASA 50 which was it’s box speed. Although lacking a mater, I metered using Sunny 16 on an overcast day at Brookfield Zoo near Chicago, and upon taking the film out of the development tank, I was elated to see a whole roll of properly exposed images.

The uncoated Steinheil München Cassar triplet produced wonderfully distinct images with very strong vignetting near the corners. Looking at the gallery above, I had to pause and wonder if perhaps I didn’t use the camera correctly. It almost looks like there was a hood on the lens which blocked light from the corners, but I made no such mistake.

I actually like the look of the darkened corners as it gives the Gewirette some character you won’t get with many other cameras, but I can’t help but wonder if perhaps this lens simply lacks the coverage needed for a 3cm x 4cm image. Perhaps this lens would be better suited for 35mm.

Coverage aside, the results were very good with excellent sharpness in the center and only moderate softness creeping into the corners. I did not shoot any color film in the Gewirette, but I have to image the Steinheil lens would have performed similarly with other uncoated pre-war lenses with a slight reduction in contrast and slightly muted colors.

Since the biggest appeal of using the Gewirette is it’s size and portability, I found the balance of the camera’s size with distinctly looking images to be a huge asset. Shooting the camera is a slow process as everything must be done methodically, to ensure you have the right exposure, focus, that you remembered to advance the film properly and cock the shutter. Skip even one of these steps and you’ll either lose or double expose an image, or have some other problem.

Although I did shoot this camera at the zoo, I would hesitate to call it a “zoo camera” which is a term I often use to refer to cameras that are quick and easy to shoot with the family on a trip to a tourist destination. The Gewirette is more of a “solo nature walk” kind of camera, that when used to it’s strengths will give you rewarding results.

With stocks of 127 either expensive or difficult to find, this isn’t a camera I’ll likely use often, but nonetheless will remain a highlight of my collection. If you are lucky enough to find a cosmetically good looking example that works properly, I definitely recommend picking one up as this is a camera that should appeal to collectors and users alike!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Gewirette

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/wirgin/wirgin.html

http://www.schaum-holzappel.de/wirgin/gewir.html (in German)

http://aya3photo.sakura.ne.jp/aya-2/wirgin-gewirette_ca.html (in Japanese)

Cool post, Mike! The USA Wirgin enterprise produced many variations of a few basic models at many market price points – niching, sort of like Jardine did with Canon RFs in the postwar years. It’s been said that you can make a career out of collecting every single variant of the Edixaflex, there are that many of ’em.

Hi Mike! What’s your recipe for developing the Supre-Tone? When in doubt I tend to stand develop, but I’d love to hear the recipe you used for this shots. They look fantastic!

I use Kodak HC-110 at a 50:1 concentration. The development water I use is “tap cold”, so roughly 50-55 degrees for 30 minutes, with one agitation at 15 minutes. I have also done it following HC-110b standard timings and got good results from that too. The cold stand option though does a better job at reducing fog though!