This is a Wrayflex Ia, a 35mm SLR camera made by Wray Optical Works Ltd. in Bromley, London, UK between the years 1953 and 1958. The Wrayflex Ia is an update to the original Wrayflex I whose only change was that it exposed 24mm x 36mm images instead of 24mm x 32mm in the original. Both the Wrayflex I and Ia models were produced concurrently, giving users a choice of film format. Both Wrayflex cameras are interchangeable lens SLR cameras which instead of using a pentaprism viewfinder, use a complex series of mirrors to provide through the lens viewing. Due to the arrangement of the mirrors in the camera, the image is upright, however it is reversed left to right. The Wrayflex series remains the only British made SLR, and did not sell well, with less than 1500 Wrayflex Ia models thought to have been made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 Wray Unilite coated 5-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Wrayflex Thread Mount (~42mm diameter)

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed Mirror Reflex

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and X Flash Sync (Marked as B and E)

Other Features: None

Weight: 776 grams, 644 grams (body only)

Manual (Wrayflex Guide): https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/wrayflex.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Wrayflex Ia is a very cool and historically significant camera that has the distinction of being the only 35mm SLR made in England. It is also based on a much earlier design that had it been built, would have been the most advanced SLR camera ever made. In this version, the camera works quite well, but as a result of the mirror viewfinder, the image is flipped horizontally, slowing down the act of shooting the camera. I didn’t have the best of luck with the image quality of this camera, but I do believe that when found in good condition, is capable of nice images. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance as the only British 35mm SLR | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.1 | ||||||

Prologue

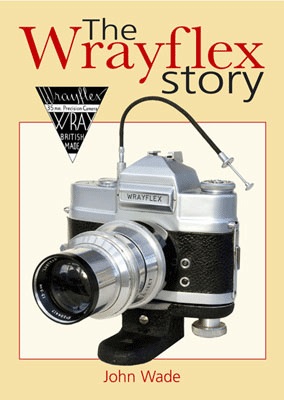

A large amount of the information obtained in the article below comes from a book called The Wrayflex Story, by John Wade. This is an excellent book with an accompanying website that tells the story of not only the Wrayflex camera, but also the Wray company themselves. The amount of information and research done by John Wade in this book is truly remarkable, and something I definitely recommend anyone interested in Wray cameras should obtain. John sells this book on his website for the very reasonable price of £9.95 with international shipping available.

A large amount of the information obtained in the article below comes from a book called The Wrayflex Story, by John Wade. This is an excellent book with an accompanying website that tells the story of not only the Wrayflex camera, but also the Wray company themselves. The amount of information and research done by John Wade in this book is truly remarkable, and something I definitely recommend anyone interested in Wray cameras should obtain. John sells this book on his website for the very reasonable price of £9.95 with international shipping available.

History

The British camera industry is filled with a variety of interesting companies and brands. Names like Ensign, Purma, Reid, and Ilford all produced cameras at one time of another with varying levels of success. Reid is known as the maker of a Leica copy that is highly sought after by collectors, Purma was best known for their inexpensive roll film camera whose shutter was controlled by gravity, and Ensign made cameras ranging from simple box cameras to fully featured medium format rangefinders.

Each of these companies were successful, at least in some way of measuring success, but of all the British camera makers, the one that was around the longest, and in my opinion, made the most interesting cameras was Wray Optical Works Ltd, or simply Wray for short.

The name “Wray” comes from a businessman named William Wray, born in Yorkshire, December 6, 1829 who had an interest in astronomy and in his free time constructed his own telescopes. At first Wray made a variety of telescopes for his friends and acquaintances, but as his reputation grew, his hobby turned into a full time business, and in 1850, William Wray turned a coach house into a workshop and created the W. Wray business.

One of Wray’s highlights from this era was in 1860 where he and another astronomer named James Buckingham who after witness a total solar eclipse on July 18, 1860 constructed a large equatorial refracting telescope of 21 inches aperture, the lens of which was made by Wray. The device, built by both men was put on display at the 1862 Exhibition in London.

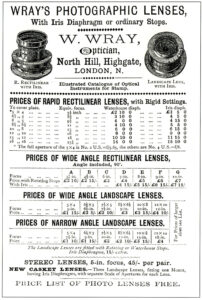

Over the next 30 years Wray’s business grew, producing a large number of astronomical devices and objectives. By the 1880s, amateur photography had grown to include a large number of camera and lens makers, and Wray, with a great deal of experience making lenses, started to create lenses for still photography. Early Wray lenses were variations of the Rapid Rectilinear lens for portraiture.

William Wray would pass away in 1885, but the company would continue on making optical products for astronomy and still photography. By 1895 Wray’s lenses started to appear in unbranded “white label” simple box and falling plate cameras. An unnamed 5½” Rapid Rectilinear Wray lens like the one seen to the left is a common lens produced by the company at this time.

The first fifty years of Wray’s business were quite successful. The company’s reputation in both the astronomy and photographic circles was very positive, but perhaps due to mismanagement by whoever ran the company after William Wray’s death, by the early 20th century, the company’s finances were in disarray. The company at this time was owned by William Wray’s granddaughters who showed little interest in the company and let control of the company fall to an employee who ran it into the ground.

In 1908, a former employee of the Ross Optical Company named Albert Smith partnered with a man named James Aitchison who had his own company that specialized in prism binoculars and was in need of someone to manage it. Smith, who was also in talks with William Wray’s granddaughters, offered to buy Wray and merge it with Aitchinson’s business. The combined company now operated under the name Wray Ltd continued to make both Aitchinson’s prism binoculars, astronomical telescopes, and photographic lenses.

The merger was successful and under Albert Smith’s leadership, in 1910 Wray expanded into a larger facility. With the breakout of World War I, in 1914 Wray was contracted by the Royal Flying Corps to make optical products for the British war effort and once again expanded into a new factory on Ashgrove Road in Bromley, Kent where the company would remain until it closed in the 1970s.

Although Wray’s business was steadily growing during the 1910s, by the early 1920s, the German camera and optics industry dominated the market and a imported photographic goods from Germany flooded the British market, making it very difficult for Wray to stand out. Between Wray and their domestic competition, the British camera market turned into a craft industry, rather than a commercial or scientific one. Small companies like Wray continued to produce photographic lenses and inexpensive goods, but nothing that could rival German companies like Leitz, Voigtländer, and Zeiss.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Albert Smith’s son, Arthur was in charge of factory operations and lens design and under his leadership, Wray produced a number of photographic lenses which were used by camera makers such as Kodak, Soho, Newman, and others. Although still a small company, Wray was going up against the sales of other highly respected British lens makers like Taylor Taylor Hobson and Cooke.

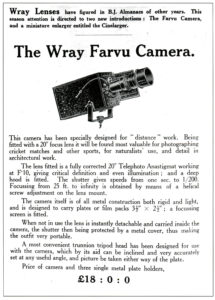

In 1930, Wray would officially get into the camera making business with their first branded camera called the Wray Farvu. The Farvu was an unusual camera built specifically for long distance photography as its only lens was a 20 inch anastigmat telephoto lens with a maximum aperture of f/10 mounted to a Compur leaf shutter. The camera was said to be designed for sport, wildlife, and architectural work so it had limited use for general photography.

By the end of the decade, war was once again in Europe and like the first time, Wray produced optical products for the British war effort. Now a bigger company, Wray’s military use products included binoculars, reflector gun sights, and aligning telescopes used with training aircraft gunners.

After the war ended, unlike after the first world war when the British optics industry dried up, now the opposite was true. With a complete absence of German products available anywhere in the world and no clear leader of the industry, demand for cameras and photographic lenses both in England and elsewhere was extremely high, giving Wray a unique opportunity to jump ahead in the market. A few other British camera makers like Purma and Ensign had been making inexpensive roll film cameras from before the war, but as of 1945, there were no 35mm models in the market.

Wray’s board of directors decided to enter the 35mm market by quickly piecing together a couple prototype options. One of those prototypes was a camera called the Owl, a name that existed before the war on a series of cheap folding cameras, but this Owl prototype had a rigid black body with a simple optical viewfinder and a 2 inch Wray Supar lens set in a removable screw mount. The shutter was of unknown construction but was said to have three speeds from 1/25 to 1/100 plus T for timed exposures. A total of six Owl prototypes were made, all slightly different from each other, but only three are known to exist today.

Upon inspection of the known prototypes, each of them were very crudely constructed with a simple shutter thought to have been sourced from a box camera. The camera itself was made of cast metal and was quite heavy. Although no evidence supports why the camera never made it beyond the prototype stage, a good guess was that even by early postwar standards, had it been released it would have been too crude a model to have been desirable by the public.

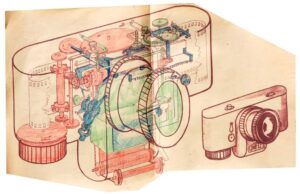

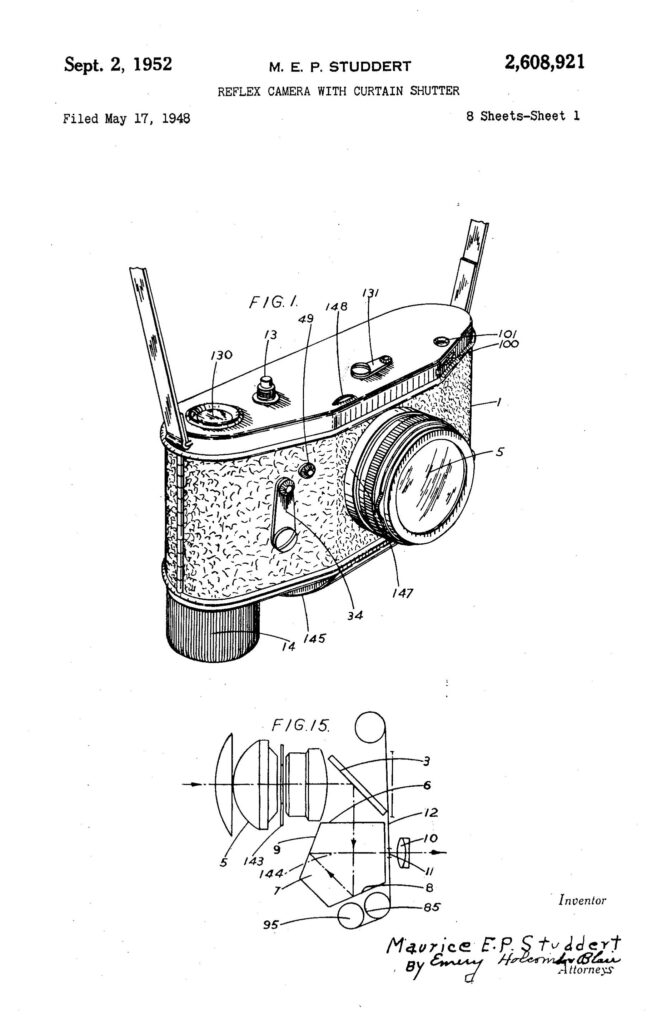

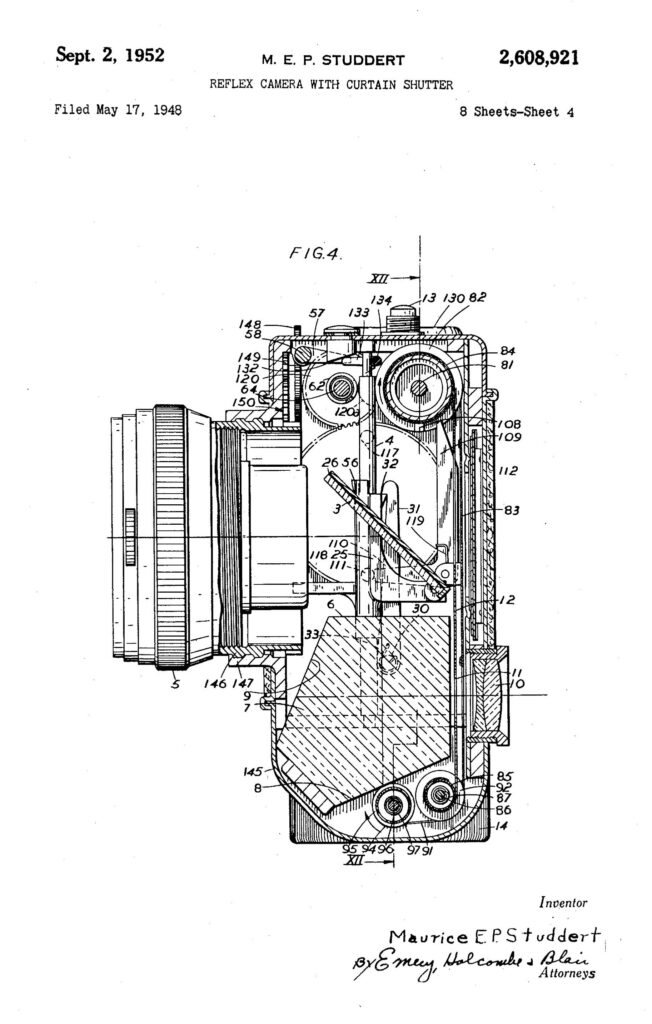

Another possible explanation for why the Owl never saw the light of day is perhaps that Wray had their sights set on something bigger and better. In 1947, Wray took out a patent on an all new 35mm SLR camera that would ultimately never be built, but had it been, it would have been one of the most advanced 35mm SLRs made anywhere in the world.

The story of this 1947 camera starts with a name named Maurice (Michael) Studdert who in 1940 was working as a Director in the Naval Ordnance Department in London. His responsibility was to oversee the development of highly secretive optical apparatus relating to military fire control and gunnery equipment. After the war, Studdert joined a team of 40 Americans who were sent to Germany to oversee the disarming of Germany and collecting technical information from German scientists. Studdert spoke fluent German and had a very high level of technical knowledge which earned him great respect among his peers and also helped in understanding the workings of Germany’s top scientists.

In 1947, Michael Studdert would leave Germany, and would travel back to England where he would join Wray along with two German technicians named Harry and Werner Goebbels who had a design for a new 35mm reflex camera. After arriving at Wray, the Goebbels would be assigned to Wray’s design department to help them develop this new camera which the Goebbels had been working on.

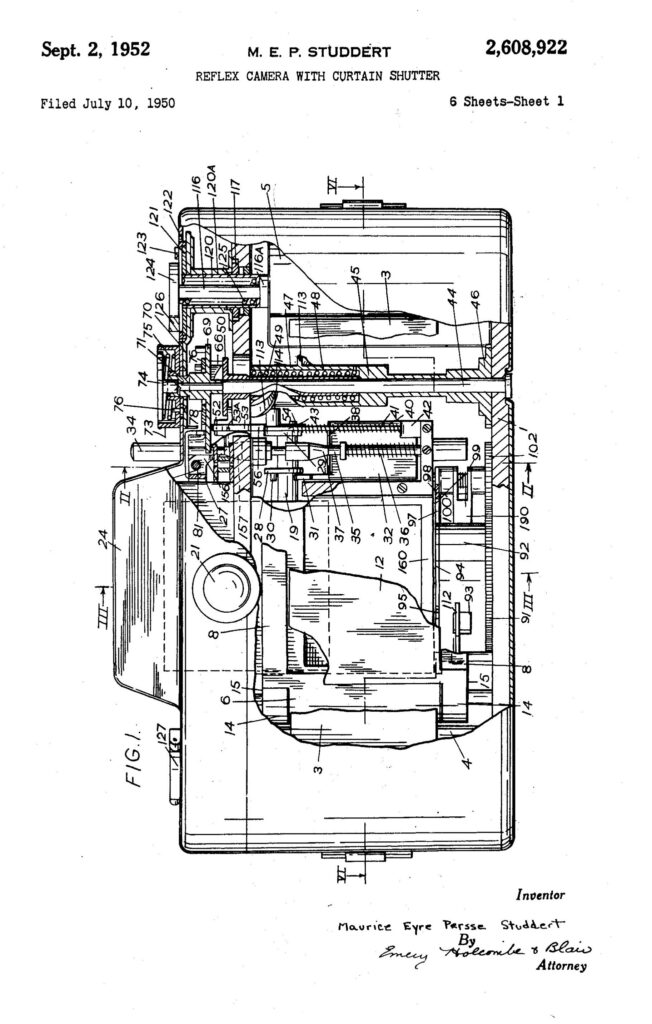

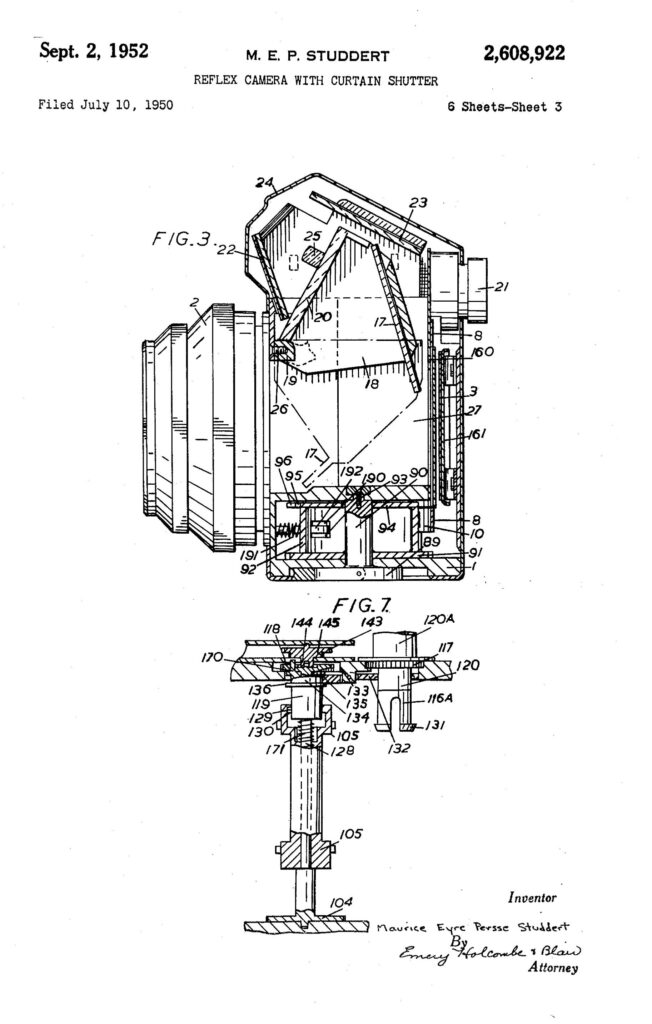

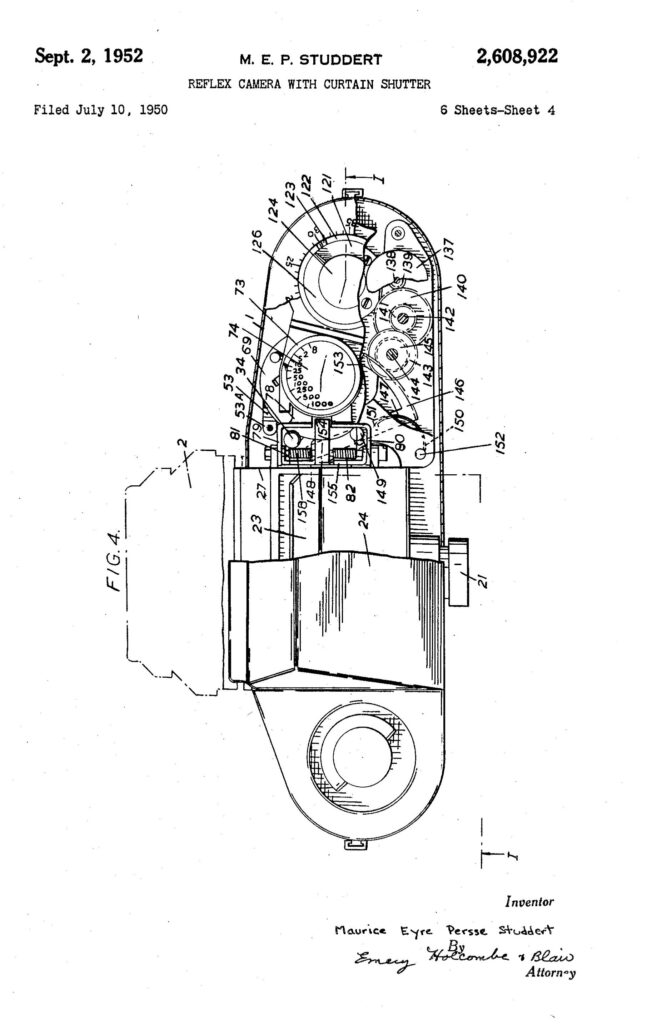

This as yet unnamed camera had four unique features that at the time were not on any other camera and a fifth not on any SLR. The first was a pentaprism viewfinder which would have allowed through the lens viewing while correcting the image on both the horizontal and vertical axis. Strangely, the pentaprism was mounted to the bottom of the camera, rather than the top, for reasons unknown. Another feature of the prism was that one surface was coated with an photo-electronic layer which powered a light meter, offering TTL metering in an SLR camera, a feature that wouldn’t be seen on another SLR until the early 1960s.

In addition, two other features of the Goebbel’s design were a spring wound film advance, which had been seen on the Berning Robot of the 1930s but never on an SLR, and the first appearance of an instant return mirror, a feature that would be released a year later on the Italian Gamma Duplex.

Finally, a feature that existed on the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and similar cameras but no other SLR was a vertically traveling focal plane shutter. Curtain rollers would have been above and below the film gate, giving the shutter curtains a shorter distance to travel over the 24mm height of the exposed image, which theoretically would have allowed for more reliable shutter operation and possibly a higher flash sync speed.

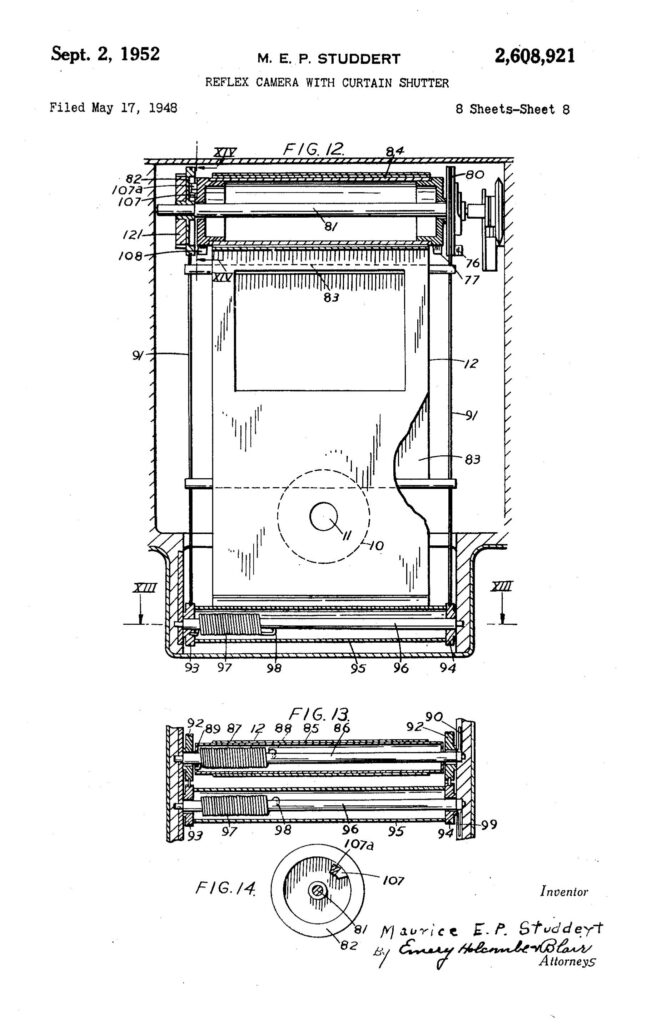

Shortly after Harry and Werner Goebbel’s arrival at Wray, in May 1947 a patent was taken out showing the design of this new camera. Two additional patents, one applied for in France in 1948 and another in the United States in 1952 show the same basic design, also listing Wray and Suddert as the inventors.

At this time, it is assumed that the Goebbels, along with Michael Studdert and possibly other engineers at Wray worked on finalizing the design of this revolutionary new camera and bringing it to production. The next clue as to what was going on happened in October 1949 when Wray registered the name for a separate company called Wray (Cameras) Ltd, a private company thought to be responsible for a new line of Wray cameras.

Unfortunately, what exactly happened between 1947 and 1949 is unclear as no evidence of a manufactured camera anywhere close to resembling the patent drawings was ever produced. Possibly adding another obstacle was that in 1950, Michael Studdert would fall ill and quickly pass away from complications of leukemia in March 1951.

Around this time, another prototype camera was revealed which was later given the name Wrayflex. This new prototype was very different from the 1947 patent SLR with none of its revolutionary features and a completely redesigned body. The camera had a manual film advance, no metering, and did not have an instant return mirror. Patent information for this camera credited a Katie Studdert and Helena Ruth for its design. It is believed that the two women had nothing to do with the camera, possibly due to Michael Studdert’s poor health, but that Harry and Werner Goebbels actually designed the camera. Reasons for the sudden switch from the original design to a much simpler one was that perhaps the complexity of the original camera was far beyond what Wray was capable of producing.

So, is the Wrayflex German or British? A few sites online, most notably a Shutterbug article written by John Wade himself call into question whether the Wrayflex is German or not. If you go entirely by patent records, credit for the design of the Wrayflex is given to Wray and Michael Studdert.

Of course, that’s not the whole story. We know that the two German technicians brought to Britain by Michael Studdert had an advanced camera already in mind before Wray submitted any paperwork. It is incredibly unlikely that these two German technicians would start working for Wray, and then instantly there be a British designed camera. So while it is entirely believable that the 1947 prototype was a German camera, patented by Wray, but what about the actual Wrayflex?

Although there is no authenticated evidence that the 1951 Wrayflex was designed by Harry and Werner Goebbels, there is still strong evidence they were heavily involved and that at least a few of the ideas from the 1947 prototype went into the 1951 Wrayflex. That neither Goebbels brothers were credited in patent documentation is likely due to not wanting to give Germans credit for a British camera, but to suggest they had nothing to do with it, seems implausible as well.

The new Wrayflex had a reflex viewfinder on the top plate, but rather than use a glass prism, used a series of mirrors that only corrected the image vertically, but not horizontally. Looking through the viewfinder, the image would be reversed left to right, the same as with a 6×6 Twin Lens Reflex. The camera exposed images that were 24mm x 32mm which is narrower than other many other 35mm cameras of the era which exposed images that were 36mm wide. This has the benefit of allowing extra exposures on a roll of film, so to accommodate this, the exposure counter on the first Wrayflex went up to 40 instead of 36.

The exact reason why the Wrayflex shot 32mm wide images is unclear, however this was something many Japanese cameras of the same era, like the original Nikon and Minolta rangefinders did. The reasons for the Japanese cameras to shoot 32mm wide images was both to account for an extremely high cost of film, but also that a 24×32 image has 3:4 aspect ratio, which the Japanese thought was a more pleasing shape.

It is unknown whether the original 1947 prototype had an interchangeable lens mount and if so, which kind, but the new Wrayflex would use a 42mm thread mount which was similar to the 42mm screw mount used by the original Contax and Praktica SLRs, but with a different pitch, making the lenses incompatible. The standard lens was a 2 inch (~51mm) f/2 Unilite lens. The lens was designed by Dr. Charles Wynne who previously worked for the renowned lensmaker Taylor Taylor Hobson. Upon its release, Wray claimed the lens had superior performance compared to any large aperture lens, even surpassing that of lenses made by Leitz and Zeiss. Also available were 50mm f/2.8, 35mm f/3.5, and a 90mm f/4 lenses. A 135mm f/4 Lustrar lens would come later in 1957 upping the total number of Wrayflex lenses to five.

Three handmade Wrayflex prototypes were unveiled in Toronto, Canada in 1950 and once again at the Festival of Britain on the River Thames in May 1951. At its launch, the Wrayflex was heralded as the most sensational 35mm camera of the past 25 years. Its unique design, innovative reflex viewfinder, and excellent 2 inch f/2 Unilite lens was the pride of Britain and was well received by the public. Although other SLRs were available at the time, these were all early designs that were quite expensive in Britain, and with a price of £95.40, it was within the reach of those who wished to have a state of the art SLR.

After its release, the British press was pleased with the performance of the Wrayflex, but sales were slow with about 850 thought to have been made. The biggest issue was with the camera’s 24mm x 32mm exposure sizes. In the early 1950s, Eastman Kodak had a strong presence in England having operated as Kodak Ltd on Headstone Drive in Harrow, North London since 1891 and with a rise in popularity with slide film, Kodak’s slide mounts were incompatible with the smaller exposed images.

The gallery above shows the original Wrayflex I with the updated Wrayflex Ia. Notice the changes to the size of the film gate, the exposure counter that goes to 40, and the differences on the bottom plate.

To overcome this problem, a Wray engineer who had joined the company in 1949 named Ron Bettell, was put in charge with making changes to the Wrayflex design. His first change was to revise the film transport and enlarge both the film gate and viewfinder so that the camera could make standard 24mm x 36mm exposures. In addition, changes to the exposure counter, the rewind switch on the base plate and a change to more standard coaxial flash sync ports were made.

The new camera was given the name Wrayflex Ia and it went on sale in 1953. Instead of coming standard with the f/2 Unilite lens, the Wrayflex was usually sold with a 50mm f/2.8 Unilux so that the camera could be sold with a price reduction of about £20. Both the new Wrayflex Ia and original Wrayflex I were sold concurrently, but other than the change in features, nowhere on the camera were the models I or Ia printed anywhere on the camera. In addition, looking at contemporary advertisements for the Wrayflex cameras, I never once saw them referred to as Wrayflex I and Wrayflex Ia, so I am not sure if this was ever an official designation, or something applied to the cameras by collectors years later.

The Wrayflex Ia certainly improved upon the original model but with only a total of around 1600 made, it still didn’t sell in the numbers Wray would have preferred. The last remaining obstacle was the mirror based reflex viewfinder with its horizontally reversed viewfinder. It was thought that the reason Wray did not initially include a pentaprism, was that at the time machining the glass to make a pentaprism would have added considerable cost to the camera and put it out of the price of most photographers. The 2 mirror system was much cheaper, but had they added a third mirror, the prism could have corrected the image horizontally.

Such a camera was developed with extra mirrors to correct the image horizontally and at least 2 prototypes, possibly a third were created. According to John Wade’s book, this prototype was called the Wrayflex Ib, but that is likely just a name given to coincide with the two other models. No dates are listed for when this prototype was made, but it is thought that it was made around the same time as the Wrayflex Ia as a proof of concept to see if such a camera could be made. That this model never went into widespread production was likely due to the fact that pentaprism SLRs were still not common in England, so it is possible Wray scrapped the idea thinking that it was unnecessary.

Eventually however, a pentaprism version of the Wrayflex, officially called the Wrayflex II was created, but not until 1959 which did have a standard pentaprism. Although it would seem that replacing the mirrors with a pentaprism would have been an easy task, due to the Wrayflex’s unique mirror box in which the reflex mirror flips up into the space between the mirrors, there was no room for a solid piece of glass. Short of completely rebuilding the entire reflex mirror box and linkage, the resulting Wrayflex II simply added the pentaprism above the mirror assembly, giving the camera an ungainly top heavy look. The pentaprism viewfinder sat above the mirror box, and the old swinging reflex design was retained.

In addition to the new pentaprism, other changes to the Wrayflex II were a switch to modern shutter speed timings. Gone were speeds like 1/5, 1/10, and 1/25, and instead were 1/4, 1/8, 1/15, and 1/30. One final change was that the rewind latch was replaced with a more traditional knob which made rewinding much easier.

Although the 1959 Wrayflex II proved to be an attractive and easy to use SLR with a small, but good selection of lenses, it paled in comparison to the onslaught of inexpensive and better supported Japanese SLRs entering the market. In addition, by the late 1950s, earlier import restrictions on German and other manufactured goods had been lifted making acquiring an imported camera much easier. Whatever advantage Wray and other British camera makers might have enjoyed immediately after World War II was gone, and with enormous competition, the Wrayflex II did little to excite customers. In total, less than 350 Wrayflex II cameras were made, making it the least common of the 3 models.

A grand total of around 2800 Wrayflexes were ever made, making the entire series of cameras quite uncommon and desirable by collectors. In retrospect, the failure of the Wrayflex had less to do with the camera’s design or the people who made it, but that it struggled to find a market. According to John Wade’s book, he mentions a camera dealer named John Lewis who worked for multiple photographic retailers and said that Wrayflexes were difficult to obtain. Distribution was poor, and in the rare case where a shop would have some stock, there would only ever be one or two at a time with orders taking up to 10 weeks to obtain. Add to that a general disinterest in SLRs from most amateur photographers throughout the first half of the 1950s, and you end up with a recipe for failure.

Wray would put their names on a few other cameras, like a 35mm stereo camera that was a rebadged Graflex model and a large format camera, but none with the prestige of the Wrayflex. Without a flagship camera or lineup of lenses, in 1962 Wray would merge with another British company called Hilger and Watts who in 1968 would be taken over by the Rank Organization who also owned one of Wray’s primary competitors, Taylor Taylor Hobson. By this point, with two companies producing similar products, Wray lost its identity and in 1971, the entire company was shut down, fully absorbed by other Rank Organization properties.

Today, British cameras occupy a pretty specific of the camera collector’s market. While never producing the number of cameras like Germany, Japan, or even the United States, there are a lot of interesting and quirky British cameras out there. The Ensign Selfix, Purma Special, Agilux 6×6, and Ilford Witnesses are all desirable, but with the Wrayflex being the only British made 35mm SLR, it stands alone in its own segment. With only around 2800 cameras ever made, they don’t show up for sale often, and when they do, prices are rightfully high, but to have the world’s only British SLR in your collection is a cool claim to be able to make, so if you ever get a chance to own one, or even play with one for a little while, I definitely recommend it.

My Thoughts

In the 20th century, there were a lot of cameras made. The sheer variety in brands, formats, shapes, and sizes of cameras from Germany, Japan, the United States, the Soviet Union and several other countries is breathtaking. If I were to come up with a generalization of cameras made by a particular country, you might say that the Germans were known for quality and complexity, the Japanese were known for precision and performance, the Americans knew how to make cheap but good cameras, and the Soviets were good at copying people.

For England however, I might have to say “taking the path less traveled”. When I think of some previous British cameras reviewed on this site, you have the Purma Special with its oddly shaped bakelite body and “gravity” shutter which changes speeds depending on how you hold the camera and there’s also the Corfield Periflex cameras which are like rangefinder cameras, but with a periscope that drops a reflex mirror in the film path for focus accuracy on a piece of ground glass like an SLR.

In both cases, the Purma and Periflex cameras featured an innovative design that no one before or after bothered to try, yet in both cases, the cameras work quite well. The simplicity of the Purma Special results in a camera that almost never fails and is amazingly accurate and flexible, and with the Periflex, you have a camera that is equal parts rangefinder and SLR, allowing you to use 39mm LTM lenses on a camera with TTL focusing.

Adding to that list is the Wrayflex. This unorthodox, yet handsome looking camera barely resembles an ordinary SLR with its very compact body and flat prism that barely extends above the top plate of the camera (the later Wrayflex II has a more normal looking prism). The designers of this camera made a SLR camera with an eye level viewfinder that works unlike any other mass produced camera before or after.

At first glance, holding the Wrayflex, you might not even realize it is an SLR. Sure, there’s a hump where you’d normally see one on a normal SLR, and if you unscrew the lens, you might see a reflex mirror, but to the unfamiliar British camera collector, the Wrayflex would be a mystery to most. For a camera made by a company without a long pedigree of making cameras, the build quality of the Wrayflex is quite good. The quality of the chrome plating, body covering, and machining of the top and bottom plates, along with the other metal bits is comparable to most German cameras of this era. With a weight of 776 grams with the f/2 Unilite lens, it is neither too heavy or too small.

Further confusing would be collectors of Wrayflex cameras, the control layout of these cameras is not typical. Looking at the top plate of the camera there is a rewind knob in the usual location, but it uses a half circle folding key that when folded down, sits flush with the top plate. While this works fine, it definitely slows you down from a normal knob as turning the key is difficult beyond a half turn. Having to rewind a 36 exposure roll of film, at only half a turn at a time is tedious and would most certainly tire out most people’s hands.

The top of the prism has an accessory shoe, and to the right is the shutter release button. Although the shutter release is in a logical location on the top plate, its location is extremely close to the side of the prism, meaning your finger will constantly come in contact with the prism each time you reach for it. Even stranger, the shutter release is externally threaded for a Leica style (but not the same) cable release which can’t be fully screwed on as it comes in contact with the side of the prism before it is fully seated. The top plate doesn’t offer a lot of space to relocate the button away from the prism, so I would have thought the front of the camera would have been a more ideal location for it.

Next to the shutter release is the shutter speed selector which has speeds from 1/2 to 1/1000 plus Bulb. Due to however the speed escapement works, there is a large gap between the 250 and 500 speeds and the Bulb position is right next to the 500 position. According to “The Wrayflex Story” by John Wade, the strange location of the B setting was due to the design of the shutter mechanism which used a shaft which when engaged would catch the second curtain, holding it open for as long as the shutter release was held down. The design of this shaft required enough room for the linkage to fit on the shutter speed selector and the only place it would fit was in this location.

Another unfortunate design flaw of this shutter speed dial is that you must lift and turn the outer ring of the selector to change speeds, however the grip around the perimeter of the dial is extremely thin, making it quite difficult to change. Its certainly not possible, but had Wray simply used a design similar to pretty much every other camera maker of the era, would have made it much easier to turn. On the plus side, both fast and slow speeds are on the same dial, and the dial does not rotate as you fire the shutter. Finally, to the right is the manually resetting exposure counter. The counter is additive, showing the number of exposures made on the current roll.

Wrayflex I vs Ia: Looking at the exposure counter is the easiest way to tell the difference between a Wrayflex I and Ia. This is a Ia model with a 36mm wide film gate which shows a maximum number of 36 exposures. The Wrayflex I has a 32mm wide film gate and has an exposure counter with a maximum number of 40 exposures.

The back of the camera has little to see other than the round eyepiece for the viewfinder. Like most SLRs, the eyepiece is centered inline with the prism. The film door is covered with the same black pebbled body covering as the rest of the camera and on this example is still in good condition, showing no signs of cracking or peeling.

The base of the camera has a rewind release button, 3/8″ tripod socket, and a very large film advance key with fold out handle. The wind knob is similar to the rewind knob with the same folding half circle handle, just larger. Like the rewind knob, turning the advance knob is difficult to turn more than half way in one single motion, but thankfully, that’s all it needs to fully advance the film and ready the shutter for the next exposure. Due to its larger size, advancing the film isn’t as tedious as rewinding film, I think that Wray’s commitment to this style of knob and half circle handle was a curious decision. The use of a 3/8″ tripod socket is not totally unexpected from a 1953 European camera, although by this time the switch to the more universal 1/4″ sockets would have already been underway. If you needed to mount the Wrayflex to a modern tripod, you’d need a 3/8″ to 1/4″ adapter.

The sides of the camera are almost mirror images of each other. The Wrayflex does not have a hinged back, instead the entire back comes off to get to the film compartment. Removing the door is done by sliding chrome latches located on both sides of the camera upward and then the back comes off. In addition to the chrome latches, two forward facing metal strap lugs are also present, allowing you to connect any type of neck strap you wish to use.

After removing the back, we see an ordinary, but crude looking film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a non removable metal take up spool. The spool has a single clip which holds the leader while loading film. You can turn the spool independently of the film transport for ease of loading. The spool rotates clockwise, which means film wraps around it in the opposite direction it is in the cassette. The inside of the film door has a smooth black metal film pressure plate without any divots or other features to reduce friction on film as it transports through the camera. The film rails and above and below the film gate are painted black, instead of bare metal like on many other 35mm cameras which suggests that Wray did not invest much thought into film transport when designing the Wrayflex. Inside the door channels and on the inside of both door latches are black fabric light seals which on this camera were all in good condition and did not require replacement.

Looking down upon the f/2 Unilite lens, closest to the body is the focus ring which has a knurled metal pattern for easy grip. The ring on my example is a bit stiff due to age, and has the side effect of unscrewing the lens if I try to force it too fast, but obviously this isn’t how the lens was designed. Focus distances are indicated from just under 3 feet to infinity. There are no markings in meters, which is curious considering where this camera was made. Closest to the front is the aperture ring with click stops for f/2 through f/22. There is no depth of field scale on the camera, nor any IR focus marks.

The Wrayflex uses a 42mm threaded lens mount, but the pitch of the threads is not the same as that of the “universal” M42 mount used by Contax and Praktica SLRs of the same era. Any attempt to mount an incompatible lens to the Wrayflex should be avoided as it would damage the threads, and almost certainly not focus to infinity. Aside from that, Wrayflex lenses go on and off the same as any other threaded mount lens, lefty loosey, righty tighty. No versions of the Wrayflex ever supported an automatic diaphragm, so none of the lenses have any type of pins or external linkages.

To the right of the mount are two coaxial flash sync ports, the top of which is engraved with a small E for “electronic”, and the lower engraved with a “B” for “bulb”. Although I could find no mention of the Wrayflex shutter’s X-sync speed, I would suspect it is probably 1/25 like other early cloth focal plane shutter cameras. The earlier Wrayflex I has both flash sync ports in the same location, but use an earlier prong type connector.

The Wrayflex’s reflex viewfinder is one of the most significant features of the camera as it offered through the lens composition at eye level, something that was still uncommon in the 35mm SLR world when the first Wrayflex first came out. This being the 1953 update which produces images that were 36mm wide, the viewfinder size is increased to accommodate the larger exposed image.

The center of the image has a round circle that magnifies the image to make focusing on objects easier, but only slightly. I found that in use this magnified part was inferior to a split image or microprism circle, and only marginally useful.

As covered multiple times in this review, the Wrayflex I and Ia models do not correct the image on the horizontal axis, resulting in images that are reversed, similar to cameras with a waist level finder. This means that when panning the camera to the left, the image moves to the right and vice versa. This is definitely something that takes some getting used to, but with practice, you can get used to doing it. People have shot waist level Rolleiflexes and Nikon Fs with horizontally reversed images for years and they got used to it.

One thing that you’ll never get used to is how dark the viewfinder is. Even with the fast f/2 Unilite lens wide open, the image is only marginally bright in the center with the sides and corners showing an extreme amount of vignetting. In anything but bright sunlight, seeing the edges of the viewing screen is extremely difficult. In my image of the viewfinder above, my smartphone did a better job of picking up the edges than it looks in person. Certainly, this is something that had the Wrayflex been more successful, could have been improved through the use of a Fresnel focus screen or other advancements that would be featured on later SLRs, but as it is now, the Wrayflex Ia viewfinder is one of the worst on any SLR I’ve ever used.

The Wrayflex is an interesting camera for a number of reasons. As the only British made 35mm SLR which features an attractive design, innovative mirror box and reflex viewfinder, and supporting lenses with excellent optical credentials, there is a lot to like about the Wrayflex. Unfortunately, as an early 1950s SLR, it came out at a time when how an SLR should look and work wasn’t yet decided upon, and some of the decisions made by the camera’s designers proved to be unpopular. The Wrayflex sold poorly for reasons which make them a difficult recommend today for someone wanting to shoot some film, but it is those same exact reasons that make them ideal for collectors. As a collector’s item, the Wrayflex has a lot to like, but if you are crazy enough to shoot one anyway, what is it like? Keep reading…

My Results

The Wrayflex is a camera that I never imagined I’d get a chance to shoot, so when I did, I was eager to test it out. Sadly, after an initial inspection, the shutter didn’t want to cooperate and would stick at all speeds. After playing with the camera and firing the shutter several dozen times, things seemed to loosen up and I started to see both the 1/25 and 1/50 speeds working. After a few more tries, I didn’t want to continue tempting fate, so I loaded up the camera with some expired Kodak TMax 100 and took it out shooting with the intent of only using those two speeds.

If you’ve been here a while and have read many of my reviews, you will know that I often stick to some of the same film emulsions. I’ve stated over and over how much I love Kodak’s Panatomic-X, but also that I often use TMax 100 as my go-to film for testing because of how predictable it is, that I like the results from it, and that I have a ton of it. An oddity of this film however, which I don’t understand is that there seems to be a difference between Kodak TMax 100 found in 100 foot bulk rolls, and the stuff that comes preloaded in commercial 36 exposure cassettes.

The results from this roll were not the best. Grain was rampant, I experienced bromide drag (when you can see faint stripes from the perforations across the image), and the contrast was quite low. Sure, there can be sample variations between how the film was stored and certainly, there’s room for error in developing, but considering I’ve gotten poor results from commercial cassettes before, I think there’s more to it. Unimpressive results aside, I still think I can make some general conclusions about shooting the Wrayflex from this single roll.

Although I could never find the exact make up of the lens design for the 5-element 50mm f/2 Wray Unilite lens, chances are, it compares favorably to other 5 and 6 element primes. If this lens had a mount that I could easily adapt to digital, I likely would have put it on my Nikon or Sony mirrorless and tried a few digital shots with it, but I just don’t like forking over the money for some kind of hand made Rare Adapter or asking someone to 3D print something for me.

Sharpness in the images I got was very good. Although the film strangely turned out dark with murky details, I could see enough to know that this lens probably is better than these images suggest. If you’re reading this wondering, “Gee Mike, for such a rare opportunity to shoot this historically significant camera, considering you got poor results on your first roll, why don’t you try again”, the answer to that question is that I just didn’t enjoy shooting the camera much.

The horizontally flipped viewfinder was more problematic than on other waist level TLR and SLR cameras that also have horizontally flipped viewfinders. A combination of a smaller image than you’d typically deal with on a 6×6 medium format camera, but also that the viewing screen was quite dark, made shooting a challenge. Combine that with a guy whose already visually impaired, a dark and difficult to use viewfinder really hampers me. Focusing the camera was difficult too. The dark viewfinder certainly didn’t help, but even with the lens properly focused, the ground glass just didn’t return a sharp and clear image. Combine that with a stiff focus ring on the lens, and I pretty much just kept the lens at infinity all the time.

The film advance key on the base of the camera was strange, but didn’t bother me too much, and the overall shape and size of the camera was pleasant, but I just didn’t love the little British SLR. The camera is attractive, but just isn’t a lot of fun to shoot, and then after seeing underwhelming results, any enthusiasm to shoot another roll was gone.

Maybe one day I’ll give the Wrayflex another chance, and if I do, I’ll certainly come back here and update this review. I do believe that under better circumstances, another photographer might have enjoyed shooting the Wrayflex more than I did, but I feel safe putting this out there with an underwhelming opinion, because frankly, there aren’t many people in the world shooting Wrayflexes! I’m not likely to update the Wrayflex fanboys!

All in all, this is a cool camera, and although I didn’t love shooting it, or the results I got, I am still glad I had the opportunity to shoot it and share with you my thoughts. If you get a chance to try one of these out, definitely go for it! It is a neat camera with an awesome history!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Wrayflex

https://www.shutterbug.com/content/wrayflex-english-slr-germany

Good Morning, MIke! Another great in depth article. I originally bought a Wrayflex 1a, but then replaced it by a Wrayflex 1, going for the original quirkiness of the “wrong” frame size. A slight correction – in the Wrayflex mirror box the mirror is rigidly linked to the ground glass screen and they both flip up. It is the focusing screen that goes up into the space between the viewing mirrors, making it impossible to fit a pentaprism in the normal place.

Another quirky British camera you may wish to look at (unless you already have done so) is the Corfield Periflex family with the unique focusing method consisting of lowering a small mirror into the light path, which moves out of the way to take the photograph.

Mikhail.

Wow — cloth focal plane shutter up to 1/1000 — that in and of itself is impressive for that era and a British, probably fairly hand-made camera. But it looks like it does not age well, and is non-standard enough to be a challenge. Still — fun to have access to such rare, vintage, working cameras.

There are a number of pre-war cameras with cloth shutter curtains with a top speed of 1/1000. In fact the second model of the beautiful Rectaflex, the 1300 has a top speed of 1/1300 and better kept example still work fine.

As to ageing of the Wrayflex, my Wrayflex 1 (and the Wrayflex1a I sold on) is in near mint condition. It all depends on how it had been used and stored.

Thank you for such an interesting read. I recently had the opportunity to try this quirky camera made in the uk a Zeus. Here is a link to my video of it – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_POuMSkdkqo

I could find only one advertisement for it on the web. Any thoughts?

Many thanks again

Andrew

Hi Mike! That was a good read, thank you!

And just a small thing – UK uses imperial measuring system, so units found on the lens doesn’t surprise me that much 🙂