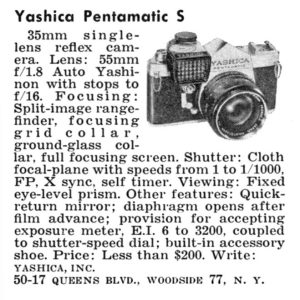

This is a Yashica Pentamatic S, a 35mm SLR camera made by Yashica Co., Ltd. starting in May 1961 through the end of 1962. The Pentamatic S was the third and final model in Yashica’s unsuccessful Pentamatic series. It featured a unique bayonet lens mount shared by no other camera, and supported features like an instant return mirror, semi automatic diaphragm, self-timer, and supported an optional clip-on coupled light meter. Upon the original model’s release in early 1960, it was a compelling mid range option for people who wanted a step up from an entry level camera, without having to spend the money for a professional model. Although built to high quality standards, poor lens availability, and reaching the market about a year too late doomed the series.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5.5cm f/1.8 Yashica Auto Yashinon coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Pentamatic Bayonet

Focus: 1.75 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Clip on Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and FP and X Flash Sync

Weight: 692 grams (body only), 1008 grams (w/ lens), 1096 (w/ lens and meter)

Manual (similar model): http://www.cameramanuals.org/yashica_pdf/yashica_pentamatic.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Yashica Pentamatic S was part of an early SLR line made by the combined efforts of Yashica and Nicca, whom they had acquired 2 years prior to it’s release. Although not indicated as such, the Pentamatic benefited from Nicca’s expertise with focal plane 35mm cameras, and had a proprietary bayonet mount, not used on any other camera. It was a well designed mid range camera that had a lot of things going for it, at least on paper. In reality, it’s arrival in early 1960 was just a little too late as nearly every other Japanese camera maker had a competing model already, and its feature set offered nothing to make it stand out. The Pentamatic series was in production for a very short time, and quickly gave way to Yashica’s lineup of M42 screw mount SLRs. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.6 | ||||||

Disclaimer: Each and every time I write a camera review, I do my absolute best to research and compile a comprehensive and accurate summary of each model’s history. I find the stories behind the various cameras and manufacturers to be fascinating glimpses of the past and one of my favorite parts about collecting.

The bulk of the information I share in each article is compiled and aggregated from a variety of sources online, from other blogs, professional reviews, books, magazine articles, and random other sites on the Internet. I make it a priority not to plagiarize any information from any other site and cite whatever references I find.

In the case of the Yashica Pentamatic, there were two sources that had already done an excellent and very comprehensive job of detailing the history of the camera and how it came to be. Each of those two sites were Chris and Carol Whelan’s Yashica Pentamatic Fanatic site, and Paul Sokk’s excellent Yashica TLR site.

What follows is my interpretation of the basic facts regarding how this camera came to be, but if you’d like to know more, please visit both Chris and Carol, and Paul’s sites as there is a lot more to read.

History

During the final months of World War II, a new Japanese company named Yashima Seiki Seisakusho, or Yashima Precision Works in English was created that made a variety of goods for the Japanese war effort. This new company’s role during World War II was nearly insignificant as the war ended shortly after it’s creation, but with the help of American aide in the years after the war, would reform as a sub-contractor of clock and other electronic parts.

Yashima’s role in the rebirth of Japanese industrialization was small, but by the end of the 1940s would expand it’s product portfolio to include optical parts used by a variety of other companies. In 1953, Yashima would partner with a Japanese distributor named Endō Shashin Yōhin K.K., or Endō Photographic Supplies and would release it’s first camera, a 6cm x 6cm Twin Lens Reflex camera called the Pigeonflex.

The Pigeonflex was heavily inspired by Franke & Heidecke’s Rolleicord, which was a popular lower cost alternative to the same company’s Rolleiflex TLR. The Twin Lens Reflex design was hugely popular in Japan at the time and a dizzying array of Rolleiflex and Rolleicord copies were made by dozens of Japanese companies, including Yashima.

In the mid 1950s, of all the Japanese companies making TLRs, Yashima had a lot of success and developed a reputation as a quality optics company. Despite their success as a TLR maker, sometime in early 1957, Yashima’s president, Yoshimasa Ushiyama saw a dramatic shift in the photographic landscape with the increased popularity of 35mm cameras, namely Single Lens Reflex cameras. Although successful at making TLRs, Yashima had no experience with the smaller designs of 35mm cameras, or the focal plane shutters that they often came equipped with. Ushiyama was concerned that if Yashima didn’t act quickly, they would quickly be passed up by other Japanese companies like Asahi (Pentax), Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta), and Miranda.

Conveniently around this time, another Japanese camera maker called the Nicca Camera Co. who had been making quality 35mm rangefinder copies of the Leica III since the late 1940s was having financial problems and was on the verge of bankruptcy. Sensing a quick and easy solution to their lack of experience with 35mm cameras and focal plane shutters, Yoshimasa Ushiyama put together a deal to bail out Nicca and combine the assets of the two companies together into a new company which would be called Yashica Co., Ltd. The new Yashica company would acquire the rights, designs, and technology of Nicca’s 35mm rangefinders, and what remained of Nicca’s lens operation would be a subsidiary company of Yashica called Taihō Kōgaku K.K.

The new Yashica company would quickly release two 35mm rangefinders in early 1959 called the Yashica YE and YF which were both based off previous Nicca designs. The Yashica YE would look nearly identical to the Nicca 3-F/Type 33 and the YF as the Nicca III-L. The Yashica YE was branded entirely as a Yashica, but the YF would have both Yashica and Nicca markings on it at the same time.

While all of this was going on with the acquisition of Nicca and release of YE and YF rangefinders, somewhere within the company, work was being done on an all new 35mm SLR camera which would later become the Pentamatic. Strangely, very little definitive information exists on the exact release date of this new camera, or who was responsible for building it. Even Paul Sokk’s incredibly detailed history section on the Pentamatic describes opinions as ‘contentious’. Apparently, there are those who believe it was released in late 1959 and others as early 1960. The only definitive dates found in regards to the Pentamatic are trademark filing dates of September 18, 1959 in Japan and February 12, 1960 in the United States. Logic would dictate that the camera was available in both countries shortly after those dates.

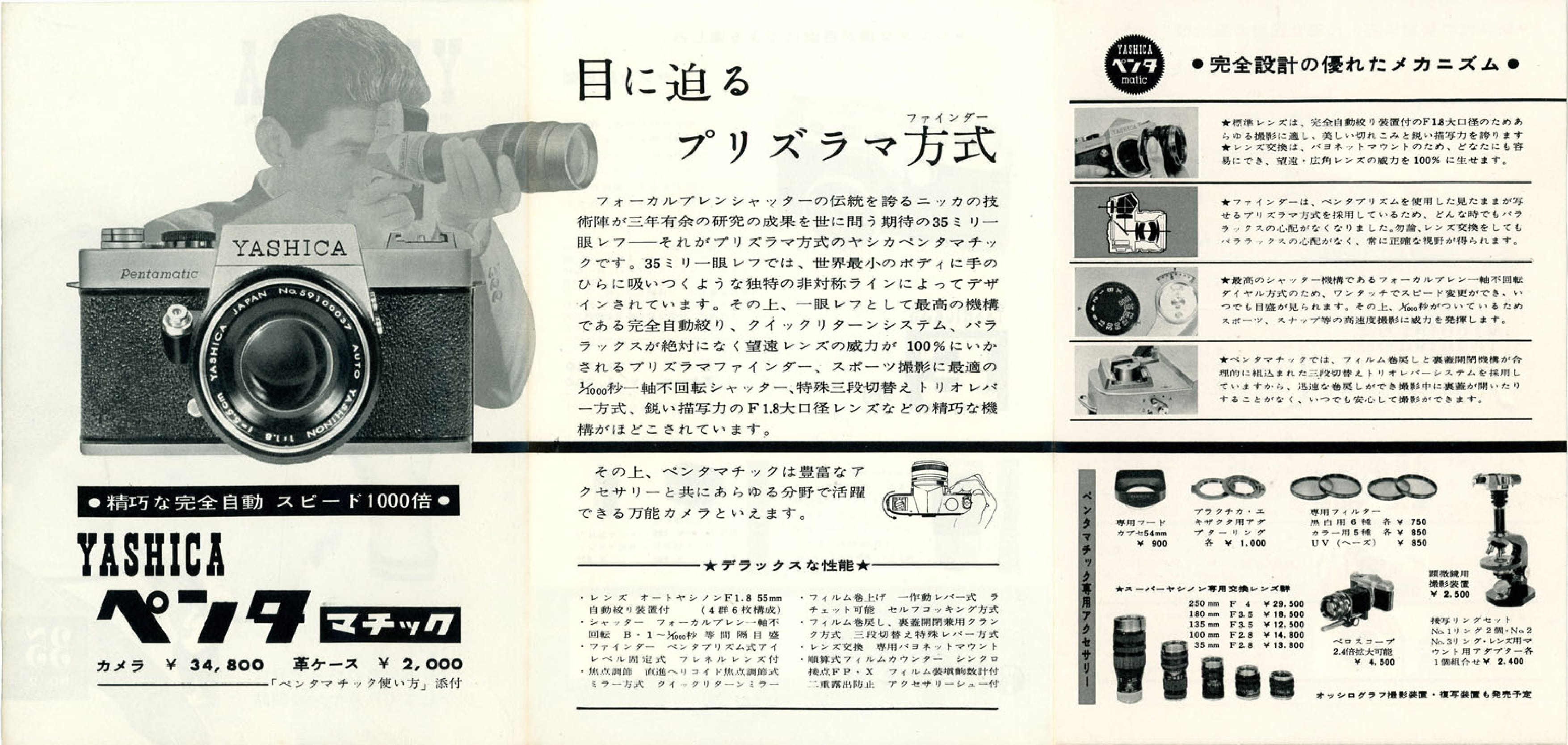

Regardless of when the camera actually became available for sale, the bigger mystery was who built it? The Yashica Pentamatic was an all new design not based on any previous camera, and as such nearly every aspect from the camera had to be designed from the ground up. It’s plausible that the cloth focal plane shutter was of Nicca design since they had experience with them, but the rest of the camera was all new. Looking at the timelines for other new SLRs like Nikon’s F, Minolta’s SR-2, and the Canon Canonflex, it generally took between 2-3 years to create an all new SLR and put it into production. If the Pentamatic was completed by the end of 1959 or early 1960 and the merger between Yashima and Nicca was less than 2 years before that, then logically, some aspects of the camera had to have predated the merger. But who started it? Had Nicca been working on a new SLR prior to it’s collapse, or was Yashima trying to put something together before they realized they needed help from another company? The only tangible clue comes from the following Japanese language brochure from 1960.

Yashica guru, Paul Sokk from yashicatlr.com had the above brochure translated into English, and it definitively says that Nicca and Yashica worked on this camera together, and that the entire development time was 3 years, which pretty much erases all doubt that work had started on elements of this camera prior to Yashima’s 1958 acquisition of Nicca.

Yashica guru, Paul Sokk from yashicatlr.com had the above brochure translated into English, and it definitively says that Nicca and Yashica worked on this camera together, and that the entire development time was 3 years, which pretty much erases all doubt that work had started on elements of this camera prior to Yashima’s 1958 acquisition of Nicca.

Now that we have conclusive evidence regarding the “who” of this camera, I feel I should at least acknowledge a very common rumor that is mentioned on several sites online that another company had some hand in designing this camera, which was the Zunow Optical Industry Co., Ltd. Zunow was a very small Japanese company who would release their own SLR in 1958 which it had been working on since 1956.

Zunow’s 35mm SLR was a very ambitious camera with features like an interchangeable viewfinder and instant return mirror that not many companies offered upon it’s release. The design and manufacturing of the camera was difficult for such a small company, so many of it’s parts were produced by various subcontractors, which caused quality control to suffer. It is estimated that less than 500 Zunow SLRs were ever built, but how does this play into the Yashica Pentamatic?

While the two cameras shared a passing resemblance to each other such as the front mounted shutter release and shape of the pentaprism, there were certainly other companies with front mounted shutter releases and similarly styled pentaprisms, so it’s possible any similarities are just coincidences. It’s plausible that one of the subcontractors that helped build the Zunow camera was either Nicca or Yashima or both. Perhaps with their increased capacity, Yashica arranged to produce some of the parts for Zunow in exchange for using the same design in their own camera? Maybe upon the release of the Zunow SLR in 1958, workers from Zunow were hired on by Yashica to help them finish their camera?

The truth is, no one knows what really happened. Zunow may have played a huge roll or none at all in the development of the Pentamatic but since it’s such a prevalent rumor, I wanted to mention it here.

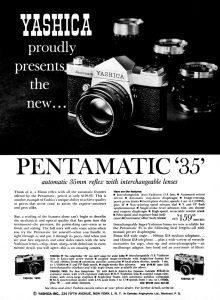

Upon it’s release, the Yashica Pentamatic was a compelling option for consumers. It was neither an entry level, nor high end camera. It lacked “pro” features like a motor drive connection and interchangeable viewfinders, but had an instant return mirror, supported lenses with a semi-automatic diaphragm, a large bayonet mount, and an integrated accessory shoe, all features that were not common in entry level cameras. The price of the Pentamatic in the US with Auto-Yashinon 5.5cm f/1.8 lens was $159.95, a price that when adjusted for inflation is comparable to about $1360 today.

Upon it’s release, the Yashica Pentamatic was a compelling option for consumers. It was neither an entry level, nor high end camera. It lacked “pro” features like a motor drive connection and interchangeable viewfinders, but had an instant return mirror, supported lenses with a semi-automatic diaphragm, a large bayonet mount, and an integrated accessory shoe, all features that were not common in entry level cameras. The price of the Pentamatic in the US with Auto-Yashinon 5.5cm f/1.8 lens was $159.95, a price that when adjusted for inflation is comparable to about $1360 today.

The biggest challenge for the new camera was one that faced nearly every maker of a new SLR with a unique mount, which was availability of lenses. Upon it’s release, in addition to the 5.5cm/1.8 kit lens, there were 35/2.8 wide angle, 100/2.8, and 135/2.8 telephoto lenses. The catch though is that each of the three accessory lenses were “pre-set” lenses which did not support the automatic diaphragm feature. Only the 5.5cm lens had it, and even still, it wasn’t “fully” automatic as the diaphragm would immediately stop down prior to firing the shutter like every other automatic lens, but it would not reopen again until the photographer wound the camera for the next exposure. Further complicating matters, Yashica did not build any of their own lenses at the time, instead relying on third party suppliers like Tomioka so the development of new lenses was much slower than other companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon) and Canon who built their own lenses.

Later Japanese language brochures suggest that two additional lenses, a 180mm f/3.5 and a 250mm f/4 were available. The issue with preset vs fully automatic diaphragms was likely due to Tomioka’s inexperience building SLR lenses as prior to the Pentamatic, their only experience was with rangefinder lenses which never needed automatic diaphragms.

In September 1960, Yashica would release a Japanese market only update to the Pentamatic, simply called the Pentamatic II which upgraded the camera to support a fully automatic diaphragm. With this new camera, a new 5.8cm f/1.7 lens became available, but the fully automatic diaphragm worked on the original 5.5cm f/1.8 lens as well.

Production of the Pentamatic II was short lived and along with the original Pentamatic was discontinued in 1961 and replaced by an updated model, officially called the Pentamatic S. The Pentamatic S retained the original semi-automatic diaphragm feature of the original model, but added a self-timer, a split image focus aide within the viewfinder, and mount for an optional clip on accessory light meter which was simultaneously released with the M42 screw mount Penta J.

The Pentamatic S and Penta J were sold concurrently with the J being offered as a lower cost option with a top shutter speed of 1/500, and compete lack of automatic diaphragm, but full support of nearly every M42 screw mount lens available at the time. All evidence of the Pentamatic S suggests this was a US-only model and never offered in Japan. Prices from advertisements suggest an MSRP of under $200 (so probably $199.95) which represented a $40 premium over the original model.

The Pentamatic S, like the entire series, did not sell well and disappeared from the company’s marketing materials by mid 1962. The M42 screw mount Penta J sold better and eventually evolved into a whole Yashica J-series of SLRs which later evolved into their TL series that remained in production well into the 1970s.

It would seem that Yoshimasa Ushiyama’s realization in early 1957 that the age of the 35mm SLR camera was upon us, but it seemed to have come a little too late. In the 4 years that followed the acquisition of Nicca, the Japanese SLR market went from a handful of models, to a plethora with nearly every Japanese company offering one or more models covering the whole spectrum of entry level to advanced professional models. On paper, the Pentamatic seemed like it should have been a compelling option, but a lack of lens selection, and coming to market a year too late doomed the series. Although Yashica would have successful M42 screw mount SLRs for well over a decade later, it would never attain a position as a leader in the industry.

Today, the Pentamatic series has a small number of very loyal fans, but is largely unknown by many collectors. I didn’t even become aware that the model existed or that Yashica had at one time designed it’s own lens mount until about a year ago, well after I started this site. My guess is that had these models been produced for a bit longer, they may have developed a more recognized reputation.

My Thoughts

The Pentamatic is quite a stunning camera and one that hints back to a very short period of time when Yashica took making a 35mm SLR seriously. The build quality of this camera is excellent and easily on par with other high quality SLRs of the era.

The sharp pentaprism hints at the standard prism of the Nikon F, but isn’t removable. The clever location of the rewind crank inside of the accessory shoe improves on the designs by professional cameras like the Nikon and Topcon RE-series that require a separate flash shoe be added on top of the wind lever.

It is a well made camera and on paper, everything was there that should have allowed it to succeed, but of course we know it didn’t.

Looking down at the top plate, we see the popup rewind knob and accessory shoe on the left. To get the rewind knob to pop up, there is a little lever beneath it on the rear of the camera which you will see later. To the right of the large pentaprism is the shutter speed selector, which on this camera is covered up by the large clip-on selenium exposure meter. This meter was designed for both the Pentamatic S and the Penta J and is interchangeable between the two models. Partially hidden by the meter is the film advance lever and non-automatic resetting exposure counter. Contrary to being an attempt at a modern camera, the Pentamatic S still requires the user to manually reset the exposure counter after loading in a new roll of film. This is done by the small saw-tooth wheel to the side of the film advance lever.

The bottom of the camera is pretty uneventful, featuring only the rewind activation button, 1/4″ standard tripod socket, and the words “Made in Japan”.

On the back of the camera, immediately behind the combined rewind knob and accessory shoe is a small lever with three positions, marked A, R, and O.

- “A” is for “Advance” and is the setting for normal operation of the camera with film in it. This setting keeps the rewind knob in the lowest position.

- “R” is for “Rewind” and pops the rewind knob into the extended position. Note that you must still press the rewind button on the bottom of the camera to allow the film transport to travel backwards.

- “O” is for opening the film compartment. With the lever in this position, you can pull upwards on the rewind knob which will release the lock on the door.

Other than this lever, the only other things on the back of the camera are the viewfinder opening, and a film speed reminder dial.

The film compartment has everything you’d expect from a modern SLR, including a left to right film transport, polished film rails, double sprocketed feeler shaft, and a slotted and fixed take up spool. The door features a metal film pressure plate with small divots for decreased resistance, and an additional door roller to aide in proper film transport.

The optional clip on meter seen here was unique to both the Pentamatic S and M42 screw mount Penta J cameras and can be interchanged between the two. By clipping it to the mount on the front of the camera, the meter entirely covers the camera’s shutter speed dial. Turning the meter’s shutter speed dial not only controls the actual dial beneath it, but also rotates the exposure calculator disc. By setting the black arrow to the appropriate ASA film speed in green, a red needle will automatically point to an appropriate f/stop which you must set on the lens for proper exposure. Although not as convenient as later cameras with automatic exposure or fully-coupled match needle systems, this was a pretty common practice when this camera was on the market.

Up to this point in the review, very little of what I’ve said about the Pentamatic S is much different from later Yashica SLRs as they all used the M42 screw mount. Of course, this isn’t those cameras, and for a brief moment in history, Yashica used their own mount. The Pentamatic mount (since it was never formally given a cool sounding name) looks like any bayonet mount you’ve seen before. Like most bayonets, there is a red dot on the lens mount at the 12 o’clock position of the flange. Line up the dots and give the lens a little twist and it locks into position. Except on mine, the lens never actually locks. There is a release button on the body near the 8 o’clock position, but I can attach and reattach the lens without pressing this button. I have to imagine that this isn’t how it was designed, and this behavior is a result of age. Then again, perhaps Yashica just did a poor job designing this mount. We never really got a chance to find out as they gave up on it less than 3 years after it’s release. At the time of it’s release, Yashica made available a M42 and Exakta mount adapter for the Pentamatic so that a photographer could easily adapt those lenses to his or her camera if they wished.

The side profile of the Pentamatic is rather busy, especially with the optional meter attached. On the very side of the top plate, we see the toothed wheel for manually resetting the exposure counter, but on the side of the meter itself, we see a chrome release button which allows you to remove the meter. This side of the camera also shows the front mounted shutter release button and self timer. Like other cameras with front mounted shutter releases like most Miranda and Topcon RE cameras, this style of shutter release is extremely comfortable for me. For one, it would be nearly impossible to reach a top plate shutter release with the meter installed, but also, it’s location allows for a much more gentle squeezing motion internal to the body that at very slow shutter speeds reduces downward pressure on the camera, which should, at least in theory, reduce motion blur. Whether there’s a practical benefit, or just imaginary, I like cameras with these front shutter release buttons.

The viewfinder of the Pentamatic is as large and bright as you’d expect from an early 1960s SLR. The mirror instantly returns, so you can compose your images before or after cocking the shutter, but one of the cost cutting measures of the camera is that the lens diaphragm remains stopped down and does not automatically re-open after the previous shot. This means that depending on what f/stop the lens was previously set to, the viewfinder can be quite dark until you re-open the iris. This isn’t a major deal, but a curious omission to the Pentamatic’s feature set.

The viewing screen has a Fresnel pattern to increase brightness and a large split image focus aide with a microprism collar to assist with focus. The Pentamatic has no internal meter, so there’s no indication of exposure within the viewfinder, nor is there any information about selected shutter speed or aperture f/stops. While the viewfinder was bright enough, and the large split image circle was useful, the thick ribs of the Fresnel screen, lack of a fully automatic diaphragm, and the complete lack of any other information really made the camera feel dated.

The Pentamatic is a strange camera. It feels well built, has a capable bayonet mount with a capable “kit” 5.5cm f/1.8 Yashinon lens, a smooth front mounted shutter release, and looks very sleek and modern. Yet it lacks what should have been “no brainer” features like a fully automatic diaphragm and an automatic resetting exposure counter. As a result, it sold poorly and was quickly replaced by Yashica’s M42 screw mount series. I wish this line of cameras had been more successful, but it wasn’t. Nevertheless, I have one in my hands, and some film, so how does it actually perform?

My Results

Reviewing cameras year round means that I have to consider when I’ll be shooting a camera when I select which film I shoot in it. For the Pentamatic, I had recently picked up some hand rolled Kodak Tri-X (type 5233) that had expired in May 1965. I figured this being a 1960s camera, I might as well use some film that might actually have once been shot in it.

If it seems like a huge risk shooting 50+ year old film in a 50+ year old camera, you’re right. The good news is this stock came from my friend Adam Paul who has a variety of very old films for sale on eBay. He had shot this Tri-X before and developed it in ice cold water using a process he calls “Cold Stand” and got some terrific results. So in an effort to recreate his results, I shot a roll of it in the cold final days of February.

It probably comes as a surprise to many people that film can still be shot half a century beyond it’s expiration date, and frankly, I am surprised every time I do it. Yet it does work.

Of course, there’s always caveats. The first is that depending on how it was stored, it may have degraded into an unusable vinegar-y mess, but even if that doesn’t happen, it definitely will have lost some sensitivity to light, but how much is anyone’s guess.

But that’s where guys like Adam Paul come in handy. Adam loves to seek out old cans of expired film sat, untouched for decades, in an attempt to shoot emulsions that aren’t being made anymore. The first thing Adam does when he gets a new “old” roll of film is take a snippet if it and load it into a modern SLR camera with an accurate meter so he can do some precise speed tests on it. He’ll shoot a sequence of 8-10 images of a well lit subject, each one at a slower and slower speed. Once he develops the film, he looks at which exposure looks most correct, and looks up what shutter speed accomplished that image, and knowing both the shutter speed and f/stop he used, he can get an idea of the current speed of the film.

The Tri-X film he sent me originally had an ASA speed of 320 when it was new, but over 50 years has since passed, and the film has lost many stops worth of light sensitivity. In his tests, he calculated that the film currently acts as an ASA 8 speed film which requires a lot more light than it would have originally.

Having this knowledge before loading it into the camera meant that I was free to shoot it without any trial and error, so I shot the film outdoors using as slow of a shutter speed as I could while still hand holding the camera, and using the lens nearly wide open. For developing, I followed Adam’s guidelines and developed it using a 1:64 dilution of HC-110 in ice cold water for 30 minutes with one agitation at 15 minutes. While the film was in the tank, I put it outside on my porch at night, where the outdoor temps were 27 degrees F.

Looking at the images, I’m very impressed both with the performance of the camera and the film. Yashinon lenses are very well regarded lenses, so I really had no doubt that the Pentamatic would produce excellent images. The additional challenge of using such old film made the whole process more fun. I could have simply loaded in some Fuji 200 and shot a whole roll of images like I often do, and they likely would have looked no different than any other images shot in a Yashica SLR, regardless if it had a bayonet or screw mount. There were a couple of light leaks in a few images, most notably the one of the old house and the tin can. Admittedly, I made no effort to shore up the rear film door, but in hind sight I should have. Of course, I don’t blame the camera for that.

Using the camera was a joy. As I’ve said a number of times, I am a fan of front mounted shutter release buttons, and with the solid weight of the camera, I always felt confident with the camera to my eye. While I would have appreciated some indicator of exposure or settings in the viewfinder, it’s not a deal breaker. I can wholeheartedly say that both the camera and it’s lens were up to the challenge. Images were sharp and contrasty, with little in the way of obvious vignetting or other optical anomalies. Of course this being black and white film, I cannot comment on any chromatic or other color-related aberrations, but frankly, I wouldn’t expect there to be any.

I wish the Pentamatic series was more successful. Yashica would continue to have success throughout the 1960s with the release of the Electro rangefinder series, and their later TL-series SLRs like the TL-Super and TL-Electro X were quite well made cameras that I can’t help but wonder what the company could have offered had they had a more unique mount and selection of bodies. Of course, they didn’t, and while these cameras occupy a very short flicker in the history of the 35mm SLR, I am glad I got to experience one.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://yashicasailorboy.com/category/yashica-pentamatic/

http://www.yashicatlr.com/Pentamatic.html

Very well done, Mike! You’ve compiled a ton of info into a very readable post. Thanks for giving the little known Pentamatic family some additional “press”. BTW, in all my years of looking at Pentamatic ads I thought I’d seen them all – the “just don’t ask it to swim” ad is a first for me!

Thanks for the kind words! My goal is always to help spread correct information about cameras online, and having both your’s and Paul’s sites made my research for this model much easier than it could have been. I’m also glad that I was able to dig up an ad you hadn’t seen before!

Very interesting review … From 1963 thru 1965 I was my high school’s “official” photographer and the proud owner of a Penta J with that clip-on meter. This was the first SLR I owned; it followed a Bolsey B2. My J outfit featured the standard preset 50mm f2 Auto-Yashinon lens, plus a 135mm f2.8 preset telephoto purchased for $29.95 from Spiratone. I covered all the usual events a school newspaper and yearbook require, and rode with both the football and basketball teams to all their away games. That Penta J also traveled to the nearby state parks, and on family vacations to Florida and the Jersey shore. It survived nearly three full years of heavy use, and then the film advance failed. A teardown revealed that the gear train was soft brass, and stripped. I had managed to save up enough money during my senior HS year to move up to a Pentax H3V badged for Honeywell. A recent examination of some Plus-X and Tri-X negatives made with the Penta J and its f2 prime reveal very good sharpness and uniform illumination corner-to-corner.

Thanks for the feedback, Roger! I actually do have a Penta J too, but something is wrong with the door release latch as I can’t get the film back open. I don’t think its as easy as the foam degrading and making the door sticky. I’ve tried quite a bit of strength to get it open and it won’t budge. For the time being, its a shelf queen. It’s certainly no surprise though that your recent review of the old Yashica negatives was positive, as Yashinon lenses have never been slouches!

As you probably already saw, I do have a review for the Bolsey B2 here, and that’s another really fascinating camera.

As always, an excellent review! I think a very fair and comprehensive look at the Pentamatic and it is always nice to see one being used rather than just being talked about. My interpretation of a couple of the historical points may be a little different but overall, in my view, a pretty accurate summation of the times. Most importantly Mike, a very enjoyable read!

As always, thanks Paul! Using the Pentamatic was a very pleasant experience, and further cements my disappointment that Yashica couldn’t have been more successful with this line.

Fantastic article about this Yashica camera. I would love to see a history of the Electro 35. My first intro to Yashica was with the TLR D and 635 series, I still own and use them from time to time. “Quality Cameras, Lens and Collectable Systems”

The Yashica Electro 35 was one of my very first articles on this site. I didn’t spend as much time on history back then, but perhaps it’s worth a read. I really should revisit that review someday and either update it, or just redo the whole thing. Hmmm… 🙂

A great in depth blog on an interesting camera, that is becoming decidedly scarce. This is one post that I shall return to time and again as it is packed with information.

Most enjoyable read. Thank you.