This is an Icarette 500/15 folding camera made by Zeiss-Ikon in Dresden, Germany around 1930. It takes 116 roll film and shoots negatives that are 6.5cm x 11cm in size making it one of the largest roll film cameras. This camera was most likely one of the higher end Icarette models as it has a high quality Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar lens with a maximum aperture of f/4.5 and a Compur shutter capable of speeds as fast as 1/250 seconds. The camera sports a leather covered aluminum body, dual viewfinders, rack and pinion focus, and a rising front standard for perspective corrected shots.

Film Type: 116 Roll Film (eight 6.5cm x 11cm exposures per roll)

Lens: Carl Zeiss Jena 11.5 cm f/4.5 uncoated Anastigmat 4 elements

Focus: 6′ to Infinity

Type: Scale Focus

Shutter: Compur Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual (similar): http://www.cameramanuals.org/zeiss_ikon/zeiss_ikon_icarette_551_2.pdf

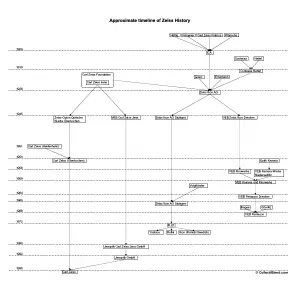

History

The name “Zeiss” has a long and storied history in the optics industry. It is a name that still exists today as a brand of high quality lenses used by many companies. The Carl Zeiss Foundation still operates as a maker of a wide variety of products in addition to lenses. As recently as 2014, the Carl Zeiss Foundation employed nearly 25,000 workers with annual sales of over 4.5 billion Euro.

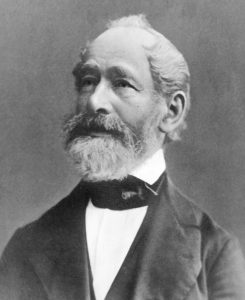

Originally founded in 1846 by physicist and mathematician Carl Zeiss as Carl Zeiss Jena. It’s first products were microscopes and other scientific instruments. The name “Jena” refers to the town the company was founded in, Jena, Germany. In 1872, Carl Zeiss would hire physicist Ernst Abbe who would develop something called the Abbe Sine Condition which improved our understanding of how light passes through glass. It was this discovery that led to the creation of Zeiss’s finest lenses. Upon Carl Zeiss’ death in 1888, the company would change it’s name to Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung (Carl Zeiss Foundation in English) and the company would continue on as a leader in the photographic lens industry.

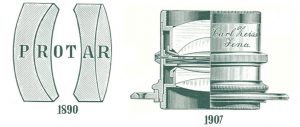

Zeiss’ first photographic lenses were designed by scientist and optician, Paul Rudolph and were called the Zeiss Anastigmat. These first anastigmat lenses had 4 elements and were released in 1889 and eventually were given the name Zeiss Protar. Over the course of the next 2 decades, Rudolph would continue to improve upon his optical formulas and would revolutionize the lens industry releasing pioneer designs like the 6-element Planar and what would become the company’s signature lens, the Tessar in 1902.

An interesting bit of history behind Zeiss lenses is that although the Carl Zeiss Foundation did make their own Zeiss branded lenses, the company would also license the optical formulas to other lens makers such as Bausch & Lomb in New York, E. Kruass in Paris, and Ross in London. This helped the company gain worldwide notoriety by quickly spreading it’s name and designs to manufacturers all around the world without having to physically expand into these markets. It was a risky move as Zeiss had to depend on these other companies to physically make their lenses true to the original designs, but it ended up working as Zeiss quickly became one the most highly regarded optical companies of the 20th century.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the German camera industry was highly successful. There were dozens of pioneering companies making all forms of innovative cameras, lenses, and other optical equipment. Aside from the George Eastman company out of Rochester, NY, the majority of the world’s photographic industry was in Germany. In 1926, four different companies (Contessa-Nettel, Ernemann, Goerz, and Ica) would all merge together with financial backing from the Carl Zeiss Foundation, and form Zeiss-Ikon. While I could not find any evidence of this in my research, my guess is these 4 smaller companies felt they could be more competitive by joining forces in the increasingly competitive photographic industry.

Although the Carl Zeiss Foundation would maintain it’s presence in Jena, the newly formed Zeiss-Ikon would dominate what would become the East German camera industry in Dresden. A large percentage of Zeiss-Ikon cameras would come with Zeiss brand lenses. It would sign contractual agreements to use Compur shutters in a majority of its mid to high spec cameras. Only the more basic cameras would be allowed to use “lesser” shutters or non Zeiss lenses.

Many of Zeiss-Ikon’s first cameras after their 1926 merger were models that were originally made by one of the companies they merged with. One of the more common models was the Ica Icarette series which had been in production since at least 1912, possibly sooner.

The Icarette was the name given to a huge variety of aluminum bodied, non-self erecting, folding bed cameras by Ica. Most used roll film, but a few were designed for plates as well. Icarettes came in a variety of sizes, shooting 116, 117, 118, 120, or 127 film. Most folded open vertically, but there were a few that folded open horizontally.

It’s worth noting that the traditional way of writing the letter “I” in the early 20th century was to write it like a capital letter “J”. As a result, many Icarettes are commonly mislabeled as “Jcarettes”.

All Ica cameras were given a model number that would usually indicate the size of the camera and what kind of film it took. The version being reviewed here is called the 500/15 which does not appear to be an original Ica model. In the 1922 and 1925 catalogs, there was something called the Icarette III Model 501 that shot 116 film, but it doesn’t look like the model I have. There were also Icarette IIs called the Model 500, but they were all 120 format cameras.

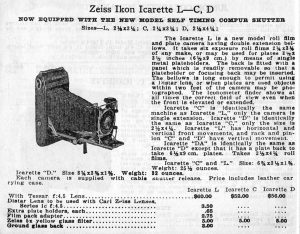

According to the information on camera-wiki.org, the Zeiss-Ikon Icarette 500/15 was part of the Icarette III series and was not made until 1930. This is supported by page 17 of the 1932 catalog for Central Camera in Chicago, IL which lists an Icarette D that shoots 116 film and came with a Compur shutter and Zeiss Tessar lens for $56. The features and dates of the Icarette D match up with what the camera-wiki article states for the 500/15. Its possible that the name “Icarette D” was given to American import versions.

In either case, the model 500/15 was likely made between 1930 – 34 and came with a huge variety of lenses and shutters. My example has a Compur shutter with serial number 1244721, a number that confirms it was made in 1930. Strangely, the Zeiss Tessar f/4.5 11.5cm lens has serial number 1928541 which suggests it was made in 1936. I cannot find any information stating that an 11.5cm lens was available on the Icarette 500/15, which suggests that this lens is not original to this camera.

As best as I can tell, after 1934 Zeiss-Ikon would discontinue most of it’s pre-merger designs like the Icarette and concentrate on their Ikonta and Nettar folding cameras, and Contax 35mm series of cameras.

After World War II, Zeiss-Ikon would be split into separate West German and East German divisions. The East German version of the company would remain in Dresden and would become a state owned corporation and it’s name would be changed to VEB Zeiss Ikon Dresden. The name would be changed once again to VEB Kinowerke Dresden in 1958 and then VEB Pentacon Dresden a year later.

The West German version of the company would continue to use the Zeiss-Ikon name as Zeiss-Ikon AG Stuttgart, but would struggle due to the weak post-war German economy and in 1965 would merge with Voigtländer, another highly regarded camera manufacturer. The West Germany Zeiss-Ikon would continue to sell cameras under it’s own name until around 1972 when the company would cease operations altogether. What remained of the old Zeiss-Ikon company would be purchased by Rollei where the “Contax” brand was revived and licensed to Japanese camera maker, Yashica.

In the decades after the war, despite the confusing state of both Zeiss brands, they would maintain their reputation as a world class camera maker, but it would be their lenses that would continue to be the “banner” product in their portfolio. Zeiss would continue to refine and improve their optics. The Tessar design would be the most copied lens design in history as manufacturers from the United States, Soviet Union, Japan, France and Italy would all have “Tessar style” lenses.

During my research for this article, I found the entire history of the Zeiss brand to be pretty confusing, especially from the 1970s – 90s, but it seems that the Carl Zeiss Foundation still existed and after the reunification of Germany in 1989, would attempt to revive the Zeiss-Ikon brand. In 2005, an all new rangefinder known as the Zeiss-Ikon ZM would be released. Built by Cosina in Japan, it would use the Leica M-mount and would be seen as a successor to the Leica M7. It would be built alongside the Cosina made Voigtländer Bessas and would use the same lenses. Although this camera is no longer made, Zeiss still has a full product page for it on it’s website.

Today, the Zeiss brand is still highly regarded and as such most of their products are appealing to collectors, so it doesn’t really matter which model you are looking at, if it has that Zeiss-Ikon logo, chances are, some collector will want it. I was very fortunate to find this camera in such wonderful condition for the price I paid for it. I’d like to think my luck was just that, luck. To find another Icarette like this in the condition mine came in would be difficult at bargain prices.

My Thoughts

I received this camera at the same time as the Voigtländer Rollfilm which I have recently reviewed. Both cameras came to me via eBay and both were in exceptional condition when I received them. Unlike that Voigtländer however, upon receiving the Icarette, I quickly noticed that something was different about it. It was MUCH larger than the Rollfilm suggesting that it was not designed for 120 rollfilm as I had hoped. Upon opening the camera, my suspicion was confirmed that this was a larger 6.5cm x 11cm rollfilm camera designed for extinct 116 format film.

Ironically, this was the second 116 format folding camera in my collection, the other being the very first antique camera I ever bought, the Kodak No. 1A Pocket Kodak. That camera came to me in August of 2014 and at that time, 116 film was just as foreign to me as 120 was. I made makeshift adapters using metal washers purchased from the hardware store, and a cut up and glued together plastic spool from one of those plastic “cakes” that 50 count blank CDs came in.

That Kodak was my first attempt at shooting any kind of vintage film camera, and my first ever experience with rollfilm. Using 120 film in a 116 camera means that the original 11cm width is retained, but the edges of the image are cut off due to the film not being as wide. This yields six 6cm x 11cm images that are slightly panoramic. The results I got from that camera were pretty good, and it encouraged me to continue exploring this hobby. As I gained proper 120 format cameras, that original Kodak got relegated to display duty and hasn’t been shot since 2014.

Upon realizing I had myself another 116 camera, I was determined not to let this Zeiss have the same fate. I was going to use it. I had a roll of Verichrome 616 film gifted to me by another collector, and I wanted to use that film in this camera. 616 is to 116 film just like 620 is to 120. The film itself is exactly the same, the difference is in the spool. 6xx film comes on spindles that are both narrower and have thinner spindles. Even though 6xx spools are smaller than 1xx spools, you cannot simply put the smaller spool into the larger camera, as the little “key” that’s in the end of the spool is also smaller. This means there would be no way for the wind knob on the camera to turn the spool while it’s in the camera. The only way to make 6xx film work in a 1xx camera is to respool it.

I talk about respooling 120 film onto 620 spools in my review for the Kodak Medalist, and that review links to an excellent YouTube video which explains the process in greater detail. Both my explanation and the YouTube video cover respooling 120 onto 620 spools, but the process to respool 616 to a 116 spool, or vice versa, is exactly the same. As long as you have matching spools, it works.

It took me almost half a year to find the time to both respool that 616 film onto a 116 spool, and also have a good opportunity to shoot the camera. So in September 2016, I took the Zeiss along with 11 others, including the previously mentioned Voigtländer Rollfilm, to Parke County, Indiana, near Turkey Run State Park to shoot some covered bridges.

The night before I left, I thought I should vet both cameras, so I went through my normal process of checking focus accuracy and confirming the shutter and glass elements were working as intended and clean. Thankfully, the shutter worked perfectly on the Zeiss at all speeds, and unlike the Voigtländer which had some internal haze, the glass elements of the Zeiss were crystal clear. This camera has been well taken care of throughout it’s life and it’s physical condition really proved that.

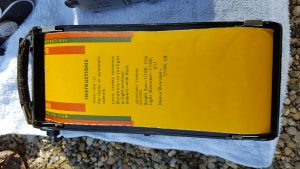

All was not well however. To my surprise, I detected some major focus issues when attempting to collimate the camera. The image to the right shows my method for checking focus using a homemade piece of ground glass, my Nikon D7000 DSLR, a long telephoto lens, and a flashlight. I won’t go into the specifics of how to collimate a camera, or why it works, as I already covered it in my article Breathing New Life into Old Cameras. Follow the link for more info, but in a nutshell, by placing a clear piece of ground glass with an X on it in place of the focal plane of the camera, and then using another camera with known good focus, you can confirm that the focus of the folding camera is accurate by pointing both cameras at one another at infinity and opening both shutters at the same time. Look at the image on the LCD screen of the DSLR to the right. If infinity is correct on the folding camera, those black marks will be very sharp. If the focus is off, the X will be blurry.

Unlike the Voigtländer which had perfect focus at infinity, the Zeiss was off by quite a bit. I found that by adjusting the camera’s focus scale to just under 30 feet (maybe 20 feet), the image was correctly focused at infinity. Even more odd, is that the focus scale had a red dot right at the 30 foot mark. Prior to this discovery, I didn’t put much thought into why that red dot might be there, but perhaps it was done by some previous owner to indicate where proper infinity focus should be?

Edit: It turns out this red dot is there as a zone focus aide in which the camera can be shot without regard to focus of objects maximizing the depth of field. There is a matching red dot on the aperture scale.

Some folding bed cameras have an infinity adjustment somewhere on the camera, but I could find no such adjustment on the Icarette. It appeared that no matter what I did, there was no way to get the camera to focus at infinity when the scale was set to infinity.

Then it hit me. When I first received this camera, I had attempted to do some research into how old this camera might be and I noticed something odd about the lens. The lens on this camera is a Carl Zeiss Jena 11.5 cm f/4.5 uncoated Anastigmat lens. Certainly a nice lens, but the thing is, I have never been able to find any information suggesting this lens was ever offered on the Icarette 500/15. Confirming this, it seems that the 500/15 was only in production from 1930 to around 1934, and the serial number of the lens dates it to late 1936. It seems that the standard lens available on this camera should have been the Carl Zeiss Jena 10.5 cm f/4.5.

Upon searching for a 11.5cm Zeiss lens, the only time I ever find anyone mention it, is when discussing large format plate cameras like the Graflex Crown or Speed Graphics. It seemed more and more evident that the lens on this camera was swapped at one point in the past for a large format lens, in lieu of whatever it would have come with originally. The discrepancy between this and the original lens could help explain why infinity focus is not obtained at infinity.

Whether that is true or not, there wasn’t much I could do about it as finding an original lens for this camera was not an option, and I saw no other way to adjust the camera, so I decided to just make a mental note to keep the camera at infinity at just under the 30 foot mark as I had detected. Since infinity was off, every other distance would be too, so I made the decision to exclusively use this camera for landscapes and not risk it with anything closer.

With my recently respooled 616 Verichrome on a 116 spool, I packaged the camera up for my adventure and went shooting.

Apart from the larger size required of 116 film, using the Icarette is pretty much like any other 1920s – 30s German folding camera. As was the case with any Zeiss camera, the build quality is superb. The aluminum body helps keep the weight reasonable, considering the camera’s size. The bellows are made of thick and supple leather. It amazes me that animal skin can retain it’s flexibility after so much time. It is always wise to check for light leaks before using any folding camera, and thankfully I detected none on the Icarette.

The back of the camera has a metal sliding door over the rear red window to seal off stray light from exposing the film. When opened, the entire rear door comes off the camera for ease of loading.

Loading film into the camera is both simpler and trickier than other folding cameras as both the takeup and supply spools have these hinged arms that extend out of the camera for easier loading. There is a metal hinge that when swung open, allows either spool to be pressed into place with ease. When everything is installed and folded back into the camera, the metal linkage holds everything tight in place. This system was clearly designed to help make the process of loading and unloading film easier, and I don’t know if somehow over time, this example loosened up a bit, but I found that in use, the hinged arms flopped around when they were extended out of the camera, negating any possible advantage to the design. Perhaps with practice, I would have gotten used to it, but it just seemed clumsy to me. Still, I give Zeiss credit for coming up with their own unique film loading method, I just don’t know that it actually helps any.

The shutter works like any other Compur shutter out there. The speeds are selected with a dial around the perimeter of the shutter. There are arms for cocking the shutter, and firing it. Aperture is changed via a sliding lever on the bottom of the shutter.

This particular design of Compur shutter has a self-timer which isn’t very obvious if you don’t know it’s there. On top center of the shutter is a little round protrusion that engages the self timer when pressed with your finger while simultaneously cocking the shutter. In the image to the left, the protrusion is visible right above the number ’50’. It is a bit difficult to explain in words, but if you just cock the shutter using the arm and not touching this protrusion, the self-timer is not engaged. When the self timer is engaged, the shutter will fire about 8-10 seconds after releasing the shutter. The shutter also has a threaded hole for a shutter release cable.

Composing an image can be done via the fold out wire frame finder, or using the brilliant reflex finder. Unlike many folding cameras, the mirror glass in this particular Icarette showed no signs of desilvering and was very bright and useful.

I generally enjoyed my time shooting with the Icarette, and it’s large size was not any more of an issue than had I been using a 120 folding camera. You always want to take special care to not bump the lens standard when shooting the camera, and also care must be taken to protect the bellows when it is extended. The Icarette has two threaded sockets for shooting with a tripod. The image to the right shows the Icarette mounted in landscape orientation on the shore of Sugar Creek, inside of Turkey Run State Park.

My Results

If you’ve skipped the top parts of this review and just want to see some results, there are a few things you should know about what you’re about to see.

- I used a roll of Kodak Verichrome Pan that had expired sometime in 1977.

- The film was in 616 format which this camera was not designed for. 616 has a different spool which would have not worked in the Icarette, but the film itself was the same size, so I had to respool the film from a 616 spool to a 116 spool.

- This was my first time ever shooting with this camera, and although I was reasonably certain the shutter was working, the lens on this camera is not original, and that caused some issues with the focus collimation. I had to remember that infinity was just under the 30 foot mark on the focus scale.

- The film was developed by hand by my friend Adam.

- Adam’s only means of scanning film is on an Epson V550 flatbed scanner. Epson does not make film holders for 116 format film, so Adam had to make his own custom film holders using black card stock.

So, that’s 5 pretty significant hoops that needed to be jumped through before any of these images could ever see the light of day. Now that they have, how do they look?

I shot these images in September, 2016, and first saw them in January, 2017. This is 40 year old film in an 87 year old camera, yet the level of detail and sharpness in them is breathtaking. I do see some softening near the edges, but nothing that would be uncharacteristic of the era. The center and off center sharpness is as good as any lens likely could have produced when this camera was made. I encourage you to view these images in a web browser and open them full screen to see all 5329 x 3033 pixels.

Some of the images show some uneven areas of exposure, most likely due to the age of the film. Most notable are the streaks in the covered bridge photo. I also overexposed the fourth image in the ravine. The suspension bridge photo is especially nice considering that bridge was swaying in the wind as I took that image. I was worried that the image would show some motion blur, but I don’t see any.

I should mention that I didn’t crop any of these images. What you see here is exactly how they came out of the scanner. The rough looking edges are due to the custom card stock film holder for 116 that Adam made. Although the look was unintentional, I think it gives it that “old timey” look like a dated photo from the turn of the last century might. The subject matter, combined with the excellent contrast of Verichrome, and that faux-framing really make you feel like you’ve gone back in time. Each of the images above could have been taken 87 years ago or 4 months ago, and they likely would have looked the same.

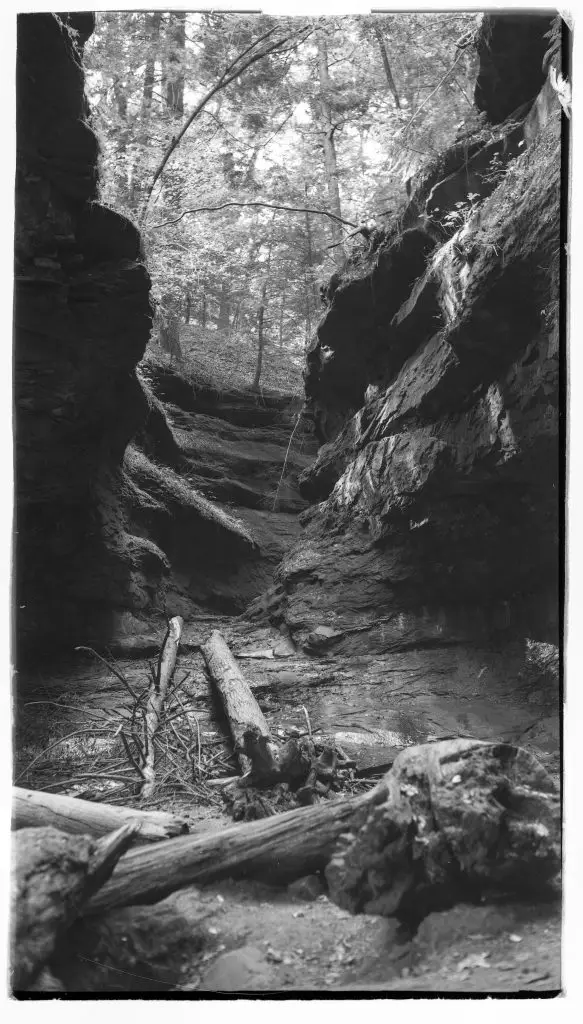

Each roll of 116/616 film should have given me 8 images, but I double exposed one, and rolled past a second frame, so I only had 6 usable images. Above are 4 of those 6, but there was one that was very blurry due to me not stabilizing the camera properly, so that leaves one more photo. I am separating this one as it’s my favorite of them all.

This image is at one of the coolest parts of Trail 3 at Turkey Run State Park in Parke County, Indiana.

This image is at one of the coolest parts of Trail 3 at Turkey Run State Park in Parke County, Indiana.

What you are looking at here is the actual trail, running water and all. You have to climb up those rocks and navigate through a very narrow crevice to continue on your path. The trail guide calls this a Very Rugged trail, and it’s not for the faint of heart, or those with weak ankles. Water resistant hiking boots with good ankle support is a requirement.

I took this shot with the camera on a tripod and I used a shutter release cable to make the exposure at approximately 3-4 seconds. I don’t know why I chose that length of an exposure, other than it just seemed right. I regret not being more scientific, but apparently I didn’t need to as the image came out perfectly exposed. Shadow detail is massive, yet what little light you can see coming through the trees doesn’t overpower the image. The image to the right was taken in the exact spot where the camera was as it captured this image.

I took this shot with the camera on a tripod and I used a shutter release cable to make the exposure at approximately 3-4 seconds. I don’t know why I chose that length of an exposure, other than it just seemed right. I regret not being more scientific, but apparently I didn’t need to as the image came out perfectly exposed. Shadow detail is massive, yet what little light you can see coming through the trees doesn’t overpower the image. The image to the right was taken in the exact spot where the camera was as it captured this image.

For comparison, I also took the same shot using my Samsung Galaxy S6 to compare. The Icarette is mounted in a portrait orientation, and the digital image was taken in a landscape orientation. I cropped the digital image to approximate the same framing as was captured on film.

For comparison, I also took the same shot using my Samsung Galaxy S6 to compare. The Icarette is mounted in a portrait orientation, and the digital image was taken in a landscape orientation. I cropped the digital image to approximate the same framing as was captured on film.

I encourage you to click on each of these images and view them full screen in a web browser. Make sure to zoom in so you can see the whole image. While the color digital image certainly looks nice, It has no personality. It just looks like any old nature pic. The black and white Verichrome however adds a whole dimension of mystique to it. What am I looking at? Where was this captured? When was it captured? Obviously reading this review you already know the answers to those questions, but they’re still worth mulling about in your head.

I am completely thrilled at how these images came out. This camera took me quite a while to get cleaned up and ready to go, then I had to jump through many hoops to get the images developed and scanned, and while I only ended up with 5 good images, I have enjoyed looking at these 5 quite a bit more than 50 that I might have taken with a digital camera.

All film has a look that separates it from digital, but when you get into these older film stocks like Verichrome, you get a look that you just can’t duplicate any more. There is no digital filter, or preset that can be applied to any digital image to recreate what we have here. These images are timeless, and absolutely worth the wait!

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Icarette 500/15 is a very nice camera made with the highest quality standards. It has a leather covered aluminum body, an excellent shutter, one of the best lenses of the day, and it came with features that were modern for the time, like dual viewfinders, a self-timer, and a unique film loading mechanism. This particular camera was in excellent condition when I acquired it, and other than an odd focus issue, has been in perfect working order for the past 87 years. The biggest shame about this camera is that it was designed for larger 116 film which is very hard to shoot these days. Had this been a 120 format camera, I could see myself using it regularly, but as it is, I will only take it out on special occasions. But that’s not because of anything wrong with the camera. This is one of the best folding cameras I’ve ever used. While I doubt these will come up for sale often, if one ever comes your way in anywhere near good condition, I would absolutely recommend picking one up! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.2 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Icarette

http://licm.org.uk/livingImage/Zeiss_Icarette.html

https://johns-old-cameras.blogspot.com/2011/09/zeiss-ikon-icarette.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-5718-Zeiss%20Ikon_Icarette.html

Even after seeing the great results of this excellent review pan out, I’m still pretty stunned at how “magical” of a result the Zeiss was able to create given the circumstances of the long-expired film. Here you took a camera with some documented focusing issues and film that expired in the original Charlie’s Angels era, and you get something amazing as a result! Here’s to another roll through this amazing camera!