This is a Kodak Chevron, a medium format rangefinder camera buit by the Eastman Kodak Company between the years of 1953 and 1956. The Chevron, like all medium format Kodak cameras from the era, used Kodak’s proprietary 620 format of film, which was nearly identical to competing 120 film, but with smaller spools. The Chevron was the replacement for the popular, but very expensive Kodak Medalist that was built during WWII and sold to civilians after. It is a large and heavy camera that shoots twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll. Like the Medalist, it has an interchangeable back allowing use of sheet film, and there was even an 828 film adapter that could be used with it.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 78mm f/3.5 Kodak Ektar coated 4-elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Adjustable 620/828 Scale Focus Viewfinder with separate Split Image Rangefinder

Shutter: Kodak Synchro-Rapid 800 Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/800 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Auxiliary Kodak Ektalux or BC Flash Holder with adjustable M, F, and X Flash Sync

Weight: 1162 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_chevron.pdf

How these ratings work |

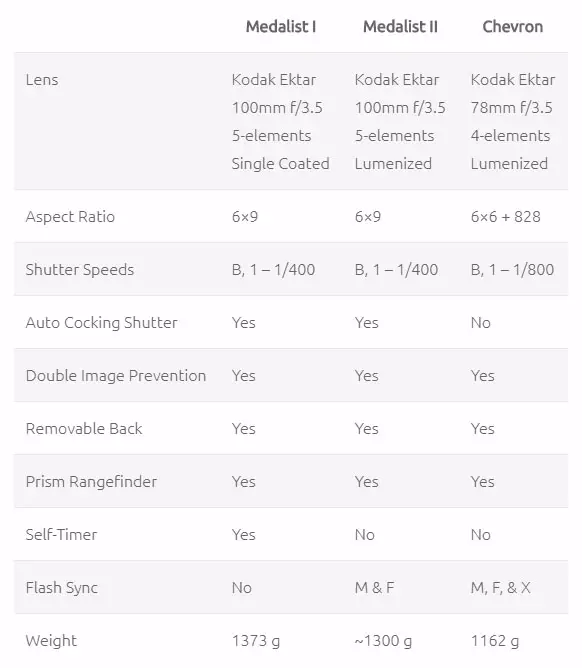

The Kodak Chevron was the successor to the Kodak Medalist, changing the format if images to 6×6 vs 6×9, upgrading the shutter with a higher top speed and electronic X-sync, but also removing some features such as the automatic cocking of the shutter. It is a large and bulbous camera that is a bit counter-intuitive for the first (or second, or third) time user. Once you get past the camera’s many eccentricities and large size, the 4-element Kodak Ektar delivers excellent results with outstanding sharpness and coverage across the entire frame. The Chevron has a steep learning curve to use, but once you get past that, it is a wonderful camera that offers a truly unique shooting experience. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for indescribable cool factor | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.4 | ||||||

History

The Kodak Chevron isn’t simply a 6×6 version of the Kodak Medalist. Sure, the two cameras share some design and functional similarities such as the combined viewfinder and rangefinder setup, the externally visible helix, and the double hinged film back, but there is a lot more that’s different than the same.

The Kodak Medalist was designed before the United States’s entry into WWII with an eye for military use. In fact, the original Medalist I was never sold directly to the public and was made for the US military, specifically the Navy. The camera was large, heavy, and over engineered. When it was slightly modified for civilian use as the Medalist II, it was also very expensive. Selling for $312.50 in 1947 which when adjusted for inflation is like $3400 today, the Medalist was out of the reach of all but the most well-off photographers.

By the early 1950s, demand for an extremely expensive and heavy camera like the Medalist was waning, so Kodak looked for a replacement model that would take the Medalist’s place as Kodak’s top of the line medium format camera. That new model would debut in 1953 as the Kodak Chevron.

Kodak knew that in order to get people to buy the Chevron, they had to make some cuts to lower the price. The most obvious was a reduction in size from 6×9 to 6×6, the Chevron is physically smaller and weighs about 150 grams less than the Medalist II. Gone was the excellent 5-element Ektar 100mm f/3.5 lens and in it’s replace was a still very good 4-element 78mm Ektar. The top plate shutter release with auto cocking shutter was also replaced with a simpler lens mounted shutter release and manual cocking lever similar to the also new Kodak Signet 35 which was released at the same time as the Chevron.

Kodak knew that in order to get people to buy the Chevron, they had to make some cuts to lower the price. The most obvious was a reduction in size from 6×9 to 6×6, the Chevron is physically smaller and weighs about 150 grams less than the Medalist II. Gone was the excellent 5-element Ektar 100mm f/3.5 lens and in it’s replace was a still very good 4-element 78mm Ektar. The top plate shutter release with auto cocking shutter was also replaced with a simpler lens mounted shutter release and manual cocking lever similar to the also new Kodak Signet 35 which was released at the same time as the Chevron.

The focusing system was also simplified in the Chevron. Instead of a brass double helix from the Medalist, the Chevron had a simplified single helix with unit mount focusing. Whether or not this had any effect on focus accuracy is probably negligible. On the upside, the focus wheel used ball-bearings to improve focus smoothness, something which is evident when comparing the Chevron to the Medalist.

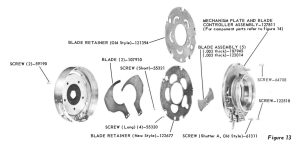

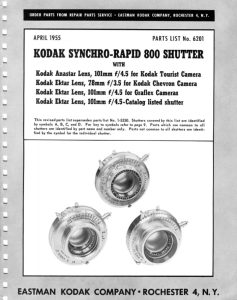

Perhaps the biggest upgrade to the Chevron was Kodak’s new Synchro-Rapid 800 shutter which at the time was billed as the “world’s fastest between the lens shutter” offering flash sync at all speeds, even the top 1/800 speed – something that no focal plane shutter can do, even today. To accomplish the feat of a 1/800 shutter speed, the Synchro-Rapid 800 employs two sets of shutter blades. The first is a rotating 5-blade shutter whose blades rotate clockwise when cocked, and rotate back counter-clockwise to make the exposure. While cocking the shutter, the unique shape of the main shutter completely opens, allowing light to pass through, so a second 2-blade shutter acts as a blackout curtain behind the primary shutter and only closes during the process of the front shutter being cocked. Here is a short video of the shutter as it is being cocked. Notice the 5 blades rotate away, exposing the two blade shutter behind it, and then reappear 180 degrees from how they were at the begining. When the shutter is fired, the blades rotate back 180 degrees counter-clockwise, exposing the film.

In the image to the right from the Kodak Synchro-Rapid 800 Shutter service manual, the 5 main shutter blades are second from the right. The larger 2 blackout blades are the larger hooked shaped pieces.

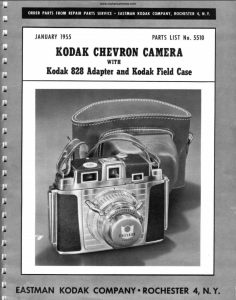

A new feature was added to the Chevron giving it native compatibility with Kodak’s smaller 828 format film through the use of an optional 828 adapter kit that Kodak charged an extra $4.25 for. The kit installed inside of the film compartment and allowed you to expose 28mm x 40mm images on 828 film. There was a mask in the viewfinder that could be positioned to change the viewfinder to show the smaller 828 frame. With the mask in place, the Chevron’s 78mm lens behaved like a 117mm telephoto lens which the Chevron’s user manual suggests is good for portraits.

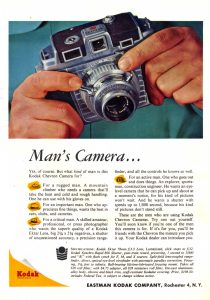

Despite these changes, the Chevron was still not cheap. Originally selling in 1953 for $215, the ad to the right from September 1954 suggests the price had dropped to $198.50 which is comparable to about $1850 today, about half the inflation adjusted price of the Medalist. In it’s marketing, Kodak hoped to capture some of that post war bravado that they used to sell the Medalist, calling it a “Man’s Camera” for big tough men, with big rugged hands. If you liked to climb mountains, or were an explorer or even a construction engineer, this camera was for you!

In all seriousness, the Chevron was big and rugged. It was Kodak’s top of the line camera during the years it was made, and the 4-element Ektar lens rendered supremely sharp 6cm x 6cm images on Kodak’s own 620 film. It was a good camera, just not one that many people were willing to spend big bucks on and as a result sold poorly. In my research for this article, I could not find any info about production numbers, but my guess is they were low. The camera was sold new until 1956, but all references to it seemed to have disappeared from photo magazines by 1955.

The Kodak Chevron would not only be the last solid bodied medium format Kodak would ever make, it would be the last precision camera of any kind marketed towards professional photographers. By 1956, the Germans had recovered from their WWII loss and the Japanese camera industry’s dominance was already in full swing, making little room for Kodak’s quirky cameras.

Today, the Kodak Chevron is a desirable, if uncommon camera for collectors. A quick eBay search for sold Kodak Chevrons returned 5 results, 4 of which were in the $200 – $300 range.

Repairs

I did not make any repairs on the Chevron as I was able to get it in working order without having to open it up. Since it was a loaner, I wouldn’t have wanted to risk taking apart a complicated camera that did not belong to me.

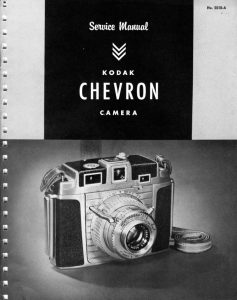

I was able to locate a service and parts manual for the Chevron, along with a service manual for the Synchro-Rapid 800 shutter courtesy of Mike Butkus from www.butkus.org that I wanted to share. These are his scans, but they are shared here for anyone who might need them. Click the thumbnail for the full PDF file.

My Thoughts

I am a huge fan of the Kodak Medalist. When I originally reviewed the original Medalist back in December 2015, I gave it the highest marks of any camera I had reviewed up until that point. It has since been superseded but remains one of my all time favorite cameras in my collection.

Knowing the close similarities between it and the Chevron, I knew I had to try one out and see how it compared. The Chevron is not only a highly regarded camera, it’s also less common than the Medalist and as a result are harder to come by, especially at the bargain prices I am used to paying. It took me a while before I found someone who trusted me enough to loan me theirs. Fellow collector and professional animator, Rudi Berden was gracious enough to send me his Chevron in early spring 2018.

Rudi admitted to have never shot the Chevron and knew it wasn’t in the best of shape when he acquired it. The camera was dirty, but cleaned up well, but more significantly, was missing the little door on the back of the camera that covers the red window when advancing the film. This caused there to be a light leak shining into the film compartment that I had to seal up with some gaffer’s tape.

Upon playing with it, I also discovered that the automatic exposure counter wasn’t working properly either. I could get it to reset to ‘1’ and sometimes it would jiggle as I advanced a test roll through it, but it didn’t stop at the correct location for the next shot. According to other owners of the Chevron, this is a common problem, and one that’s not easily fixed.

Considering this was a loaner and I didn’t want to fiddle around inside of the camera, I made the decision to use the red window on the back of the camera for every shot. Since I also had no door to cover it up with, I also covered the door with tape that I would peel back and peer under each time I needed to advance the film. Certainly not as glamorous as a properly working Chevron, but I’ve jumped through smaller hoops to get other cameras working so I didn’t mind.

The Kodak Chevron is an imposing camera for anyone whose never held one before. It might have a reputation as a “downsized” Medalist, but it’s still quite a large camera. Thankfully, the bulk of the camera is made from aluminum, so it’s not as heavy as it could have been, but this is certainly not a pocketable camera, nor one I’d want hanging from my neck for prolonged periods of time.

The top of the camera has two large strap lugs on opposite ends, with the exposure counter, an elegant Kodak Chevron logo in the middle and a selector for a viewfinder mask that is needed when shooting 828 film in the camera. To change the mask, you use a coin to turn a little dial from 620 to 828. I suspect that an overwhelming majority of Chevrons never shot 828 film making this feature unecessary, but it’s there if you need it.

The back of the camera has the central red window surrounded by a film reminder dial that shows various Kodak films of the era. Normally, there should be a horizontal metal lever protruding out of the smaller hole to the right of the red window, but for some reason, it is missing from this camera. I cannot think of any reason anyone would remove it as that hole goes straight into the film compartment letting light leak in. You can clearly see the residue of old tape that someone had used in the past to cover up the back of this camera, something I would need to do also if I were to shoot it.

Like the Medalist, the Chevron is hinged on both the left and right sides of the camera which means you can swing the camera open in either direction, or completely remove the back altogether. Unlike the Medalist however, the Chevron has different hinges that resemble other Kodak cameras of the 1950s like the Signets 35 and 40 in which you press in a little release button and slide the entire hinge up to release it. Not that you would want to do this anyway, but this means the back from a Medalist would not be interchangeable with the Chevron even though they look similar.

With the back of the camera off you see the film compartment. Had this been a 120 roll film camera, I would say it loads like any other roll film camera, but since it’s a 620 camera and a Kodak, I’ll say the loading process is…complicated, but not as complicated as the Medalist.

Kodak designed the 620 film format using 120 film stock, but on smaller and thinner spools. Knowing that some people might try to use thicker 120 film in a 620 camera, they designed the film compartment on the Chevron to be very tight and cramped. Many articles online suggest that you can simply file or shave the plastic flange off a 120 spool to make it fit into a 620 camera, and that might work on some cheap Brownie box or folding cameras, but its a really bad idea on the Chevron. I strongly advise not trying to modify a 120 spool to use it in this camera. The first thing you’ll need to do is respool some 120 yourself onto 620 spools or buy some film from a place like the Film Photography Project who has already done this for you.

If you’ve never respooled film before, it is not hard to do. I’ve talked about it in other articles before, so I won’t repeat myself too much other than to share with the video I recommend that shows the exact method I use. You’ll need two spare 620 spools, one for the supply and one for the takeup side, so if you have a Chevron, hopefully it came with at least one in the film compartment. You’ll also need some place dark to do this in. It doesn’t have to be a proper photography dark room, a dark basement or bedroom works fine, as does a film changing bag. Ive even done it in my living room while watching TV with the lights off, by using a black backpack.

Once you have your roll of film rolled into a 620 spool, it is time to insert it into the camera, which mostly works like other roll film cameras other than the Chevron’s film compartment is very tight. You absolutely must press both sides of each spool into it’s chamber with even pressure. You cannot insert the spool at any kind of angle. The Kodak Chevron’s manual suggests not attempting to thread the paper leader onto the take up spool until the supply spool is fully inserted.

With the camera loaded and ready to go, it is time to shoot some film. Using the Chevron is simpler than the Medalist, but can still be a complex affair for a novice.

From the front of the camera, Shutter speeds and aperture settings are changed via rings around the front of the camera. The Chevron has no self timer, instead there is a slider for flash sync delay which you can ignore unless you are attempting to use flashes with your Chevron. The shutter release is a long metal bar near the front right edge of the shutter. Unlike the Medalist, the Chevron does not have an auto-cocking shutter. This must be done manually after advancing the film and before firing the shutter. In the image to the right, the cocking lever is directly above the 100 shutter speed setting.

In the image to the right, we can see that the front lens element of the Ektar 78mm lens shows a yellowish tint, which suggests the use of radioactive Thorium Oxide coatings. Kodak used this coating on many lenses from the late 1940s through the 1960s. Although scary sounding, the amount of radiation these lenses give off is very low. Sources online suggest that the measured amount of 10 mR/hr is less than what a dental x-ray emits.

Assuming the exposure counter on your Chevron is working, winding the camera requires you to first press and hold the “film-advance release lever” on the front of the camera, beneath the right rangefinder window, while simultaneously pushing a lever on the cameras left side several times until it stops moving which indicates the camera is ready for the next exposure. This lever replaces the traditional knob wind of the Medalist as a sort of early “rapid wind” feature. Kodak used a similar wind lever on their high end Kodak Ektra 35mm camera.

If your camera has an inoperable exposure counter like this one, you still use the same winding lever and release lever, but it will never stop at the next frame. Instead, you’ll need to use the standard red window on the back of the camera to keep an eye on the 12 exposure numbers on the backing paper of the film. In my case, I had a piece of black tape covering the red window since someone had previously removed the door that normally covers the window, so I had the additional step of also having to peel back the tape to see the numbers on the red window. As with any old camera with a red window, make sure that you do this in subdued light. Advancing film in subdued light was common practice back when these cameras were new, but consider that today you are likely using film that is significantly faster and much more sensitive to light than the films that were available when these cameras were new so extra caution to protect the red window from excessive light is important. In 1953 when this camera was made, Kodak Ektachrome Daylight film had an ASA film speed of 8, which is more than 4 stops faster than Kodak Portra 160 is today. Kodak Verichrome Pan film was ASA 64 which is 3 stops faster than Ilford Delta 400.

The differences from other 1950s rangefinders continues with the viewfinder. Typical of other cameras of the day, the Chevron does not have a combined viewfinder and rangefinder where you can see both at once. Unlike other cameras like the Barnack Leica or Argus C3 in which the viewfinder and rangefinder are contained in two separate windows, Kodak conveniently puts the rangefinder within the same eye piece, immediately below the main viewfinder. If you position your eye just right, you can actually see both at the same time.

The viewfinder correctly shows the full 6cm x 6cm frame (or a smaller 828 view if you turn the little dial on top of the camera), but the rangefinder window is a magnified portion of the center of the frame. The magnification allows for precise focus in the center portion of the window, but you cannot see the entire exposed image while using the rangefinder. For some people it can be a little distracting trying to find the exact center of whatever it is you are trying to photograph when using the rangefinder. Kodak believed that this style of magnified, but separate rangefinder was superior to the dim combined rangefinders that were becoming popular with other manufacturers. This is the same exact system that Kodak used on the Kodak Medalist, so anyone familiar with that camera should adapt quickly to the Chevron, but if you’ve never used either camera, it does take some getting used to.

The image to the left is my best attempt to capture both the main viewfinder and rangefinder in the same shot. It was incredibly hard to get this and you cant really see the split line in the rangefinder. I assure you though, it looks better in person.

Thankfully, the view through both of the viewfinder and rangefinder windows is generally clear and bright. Unlike later cameras that would use mirrors and beamsplitters to create a split image, the Chevron uses glass prisms in the rangefinder which has the benefit of not suffering from “desilvering” like many period beamsplitters do. If you are adventurous enough, the prisms can be easily cleaned with simple glass cleaner if you remove the top plate, giving a view that is likely exactly how it was when the camera was first built.

The Kodak Chevron is definitely not a camera you can just pick up and go. Whether it’s your first, second, or even 100th time shooting this camera, care should be taken to familiarize yourself with the controls so as to avoid any hiccups while out shooting. As complicated as everything probably sounds reading this article, once you get used to the camera, it is really not that bad to use. Having shot a Medalist a number of times, I felt right at home with this Chevron and I think anyone who spends enough time with one, will too.

My Results

I had a trip planned downtown Chicago to visit Central Camera and then take my family to Lincoln Park zoo in May 2018, so what better chance to showcase the sharpness that I had hoped the Chevron would be capable of, than a trip in the city. The night before our trip, I respooled a fresh roll of Porta 160 film into a 620 spool and loaded it into the camera.

As with the Kodak Medalist, the Chevron requires a very specific film loading process to get the exposure counter to work correctly. As it would turn out, the exposure counter on this Chevron was not functioning correctly, and knowing that the flap that covers the red window on the back of the camera was missing, I made the decision to cover the back of the camera with black electrical tape and peek under it when advancing the film so I could use the exposure numbers on the film’s backing paper. This was certainly not as elegant than had the exposure counter been working, but it was an acceptable compromise for me.

Having shot my Kodak Medalist a number of times, I was prepared for some nice images, but I wondered if I’d notice the change to a 4-element design, and the addition of the Lumenized coating that my original Medalist lacked. I thought that perhaps colors would be more vibrant, with a hint of softness near the edges.

It turns out, I was right on one, not so much on the other. The colors were certainly vibrant, especially considering I had used Kodak Portra 160, a film noted for muted colors, but I was wrong in being able to detect any hint of softness near the edges. The exposures from the 4-element Ektar look just as sharp and well defined as those from the 5-element version. Perhaps the slightly wider 78mm lens construction negated any possible ill effect from the simpler lens formula, or possibly that both lenses are so well designed that it really didn’t matter.

It’s a shame really, that Kodak never could quite get the hang of making cameras that could compete with the Germans. There was no Kodak version of the Leica or the Rolleiflex, but had there been, I think their Ektar lenses would have been every bit as good as the Zeiss Sonnars and Tessars, Voigtländer Heliar and Skopars, or any other number of quality German lenses. I would be shocked if any meaningful difference could be detected between an image shot on the Chevron with the Ektar lens compared to a 6×6 German camera of the era.

The Chevron certainly isn’t for everyone. It’s not a simple camera for a beginner (or even intermediate amateur) to pick up. It’s big, heavy, the controls are awkward, and there are a lot of extra steps required to shoot it. But therein lies it’s charm. I said the same thing about the Medalist in that this thing is a very unique piece of camera history and no one else made cameras like these. Shooting a Chevron requires patience and concentration, but if you’re willing to put in the necessary energy, you will be rewarded with not only an experience unlike that of any other camera, but also some really fantastic photographs!

I’ll still say I prefer the Medalist over the Chevron, but only slightly. The need to manually cock the shutter after winding the film is an unnecessary requirement for a camera that cost as much as this did, and although I appreciate the economy of 12 exposures per roll versus 8, I feel as though the smaller size of 6×6 is better suited to small folding cameras or Twin Lens Reflex cameras, than a large solid bodied rangefinder like this. They’re not very common, and not very cheap, but if you have a chance to pick one up, I absolutely recommend it.

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Chevron

https://sites.google.com/site/harrissonphotographica/home/kodak-chevron

http://www.bnphoto.org/bnphoto/KodakChevron2.htm

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-1724-Kodak_Chevron.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/kodak-chevron-camera.295450/

That is one stylish camera. Am excellent comprehensive review as usual Mike. When I asked a trusted repairer about these years ago he commented that he had never seen one working, and wouldn’t care to fix one, so I let the matter drop. I was able to get a Medalist ii repaired easily, and have grown to love it.

The image quality on these shots is amazing. Kodak had a lot of low end cameras they made but the lenses were very respectable. Love your posts. Always required reading. Keep up the good work.

One major problem with the Chevron is the unreliability of the shutter. Like the early Contax cameras the concept was great but the execution left a lot to be desired.

Nice comprehensive write up on the Chevron! I picked up one a while back online and I love it! I love the older Kodaks and their uncommon handling. The Chevron is a great mixture of both function and art. Mine has a slight issue with the feature of the advance lever that is supposed to lock once you wind to the next frame. When I push in on that little tab on the front after snapping a picture, I have to carefully watch until the tab pops back out fully and advances to the next frame on the counter. Otherwise, it is easy to just keep winding on and messing up your spacing on the film. It’s only a minor inconvenience really. The camera’s Synchro-800 shutter works great, even at the slow speeds, which I have heard is rare for the Chevrons, but for a camera that has not (to my knowledge) been serviced, what more can you ask for? It’s one of the earlier serial numbers, so I am guessing from 1953. It’s such a robust camera and handsome if I do say so myself. Kodak produced some great cameras around this time (Medalist, Chevron, Signet), much better looking is form and function in my opinion than the foreign competition.

Regarding your comment “There was no Kodak version of the Leica or the Rolleiflex..,” there was the Kodak Reflex camera (I and II) that were very competent TLR cameras. That 80mm Anastar lens on the Reflex II is tack sharp and it was, I believe, the first camera to use a Fresnel lens. It has a very bright viewfinder. Many of the foreign cameras used the Fresnel lens later on. It also had a great frame counter, very robust. But I agree with you, had Kodak released more cameras with the Ektar lenses, they would be just as good, if not better, than the sonnars and tessars.

I truly believe that the Ektar lenses on the Medalist and Chevron cameras are just as good as what is available in new systems today. Kodak knew what they were doing!

Hi Mike I really like your reports

Thanks for your thoughts

They are very well written and you have done a fantastic research

Since I read the items I have taken out my Chevron and sadly found that the shutter was not working the second blade did nit open

I said the cameras to Chicago Cañera (I saw it in your article) and they are fixing fir me and the price they quoted me it was just ok

But I bought 2 more on E bat on perfect condition and yesterday bought another one

I am using the 620 adaptor and using black and whit I am developing in between office work

The pictures are perfect

I also have used 620 film and I have adapted a cold shoe using an square finder from China high makes the cameras great

I have several Medalist and I negelected the Chevron for years but thanks to you brought them back ti life

Alejando

Thanks for the response Alejandro. Unfortunately, you are not alone with your dead Chevron. The Kodak 800 shutter was very complicated, using two different sets of shutter blades to accomplish the higher speeds, and are more prone to fail than other leaf shutters, including the one on your Medalist. I also reviewed the Kodak Tourist a while back and the highest spec version of that camera has the same shutter as the Chevron, and the example I had was dead too.

The Kodak Chevron was notably used as a prop in the MAS*H TV show. Both Hawkeye and Frank Burns can be seen using one in several episodes.