In last week’s Keppler’s Vault, we talked about the concept of a Beam Splitter Reflex in which an SLR viewfinder is designed to use an optical device called a beam splitter that would both pass light through to the film plane and up into the viewfinder without any moving parts. The concept had some definite pros, but also some difficult to overcome cons that clearly couldn’t be overcome as the main prototype discussed in the article was never produced.

This week, we’ll talk about a no less technically difficult design of camera that actually was produced, and for a brief while, was actually pretty popular, the Leaf Shutter Reflex.

Before I go any farther, it is important to understand what the difference is between a Leaf Shutter Reflex and a normal Reflex camera with a focal plane shutter. In it’s simplest form, a Leaf Shutter Reflex is an SLR with the same kind of shutter that you would often find in most earlier folding and rangefinder cameras. Leaf shutters usually have 5 blades and open from the center out, almost like a flower petal. The German Compur and Prontor shutters were two of the most popular types of leaf shutters of the 20th century and had designs that were often copied and sold under names like Vebur, Cludor, Seiko, and Citizen.

Before I go any farther, it is important to understand what the difference is between a Leaf Shutter Reflex and a normal Reflex camera with a focal plane shutter. In it’s simplest form, a Leaf Shutter Reflex is an SLR with the same kind of shutter that you would often find in most earlier folding and rangefinder cameras. Leaf shutters usually have 5 blades and open from the center out, almost like a flower petal. The German Compur and Prontor shutters were two of the most popular types of leaf shutters of the 20th century and had designs that were often copied and sold under names like Vebur, Cludor, Seiko, and Citizen.

Here is a video showing the shutter firing on a variety of Leaf Shutter Reflex cameras, some of which are quite uncommon!

A focal plane shutter is one that is typically made of cloth or metal blades that either travels horizontally or vertically. As their name implies focal plane shutters exist right in front of the focal plane where the camera’s lens focuses the image on the film (or digital sensor).

Ever since the first models made by Ihagee, KW, and Pentacon, SLRs typically had focal plane shutters as they allowed for a faster shutter speed of 1/1000. Eventually, 1/2000, 1/4000, and even 1/8000 shutter speeds were available whereas the average leaf shutter topped out at 1/500, sometimes even less.

In a rangefinder or folding camera, the position of the shutter is not all that important. Although focal plane shutters are in front of the focal plane, it doesn’t need to be there, but in an SLR, with the reflex mirror, the position of a focal plane shutter behind the mirror allows the shutter to always stay closed while the mirror is in the down position, reflecting light up into the viewfinder.

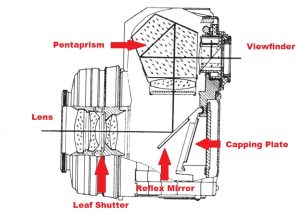

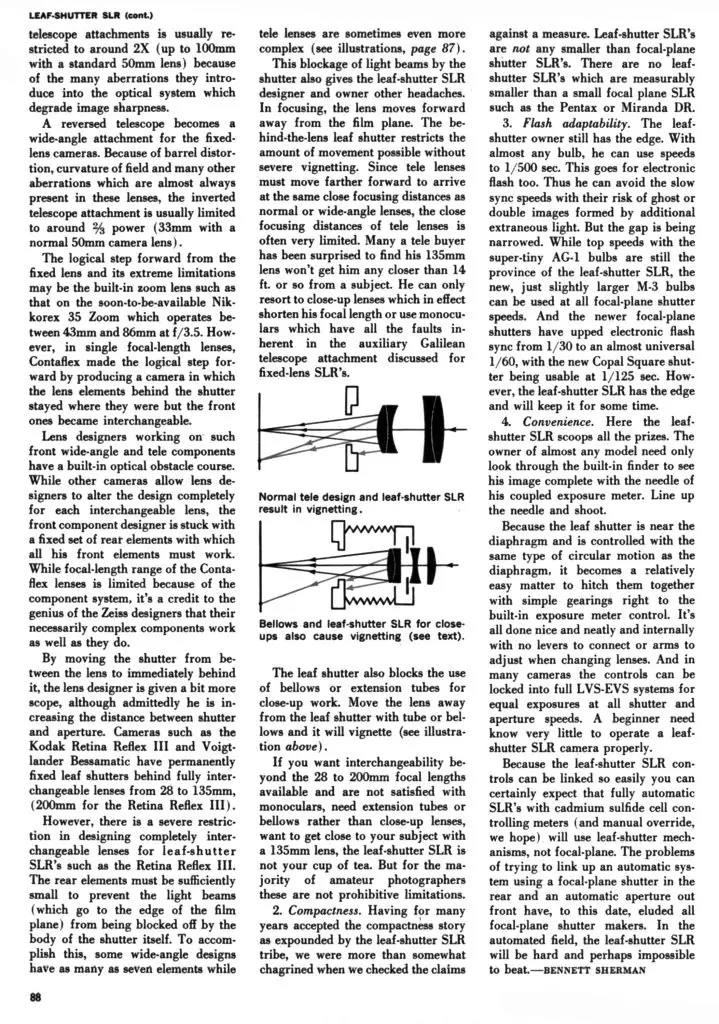

With leaf shutters, their thickness and complexity required them to be in front of the mirror. This poses a huge problem as in order for a reflex viewfinder to work, light must be able to pass through the lens, reflect off the mirror, and up into the viewfinder. But if the shutter is open, then you need some other device to prevent light from going around the mirror, and exposing the film. To prevent this, leaf shutter SLRs have an additional plate, usually called a capping plate that exists behind the mirror that will close when the mirror is in the down position and the shutter is open.

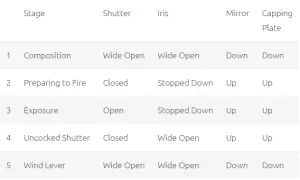

While a photographer is composing his or her image, the shutter is open, mirror is down, and capping plate is down. When the photographer wishes to make an exposure, the shutter needs to close and both the mirror and capping plate need to flip up (or down) out of the way to allow light to pass through to the film plane, thus exposing the image. After the image is exposed, the shutter closes again, capping plate and mirror drop back down, and then the shutter re-opens in order to allow light to enter the viewfinder again.

While a photographer is composing his or her image, the shutter is open, mirror is down, and capping plate is down. When the photographer wishes to make an exposure, the shutter needs to close and both the mirror and capping plate need to flip up (or down) out of the way to allow light to pass through to the film plane, thus exposing the image. After the image is exposed, the shutter closes again, capping plate and mirror drop back down, and then the shutter re-opens in order to allow light to enter the viewfinder again.

This multi-step dance requires a lot of moving parts that all need to work together in order to function reliably. The shutter is essentially firing twice for every exposure, doubling it’s wear and tear. That’s not to say that a focal plane shutter doesn’t also have moving parts that need to work correctly, but the whole process is just simpler.

So if a leaf shutter SLR is so complex, why do it at all? There have to be some advantages, right?

There are two primary benefits to leaf shutter SLRs, the first is flash sync speed. Because a leaf shutter must always open up all the way before it can begin to close again, a leaf shutter supports both flashbulb and electronic strobe flash sync at all speeds, up to 1/500.

In a focal plane shutter, faster speeds require the second curtain to close before the first one finishes opening. In order to properly expose an image with flash, the maximum flash sync speed is limited to only those speeds in which both the first and second curtains are completely open, which on earlier horizontally traveling focal plane shutters, is between 1/25 and 1/60. With the advent of vertically traveling focal plane shutters such as the Copal Square shutter, flash sync speed increased to 1/125. Even today, the professional level Nikon D5 DSLR has a maximum flash sync speed of only 1/250. If you want the fastest possible flash sync speeds, you need a leaf shutter.

Another problem with most focal plane shutters, is that at their fastest speeds, they can introduce a rolling effect in which the subject being photographed moves in the short period of time when the shutter first begins to open and when it completely closes. Without getting too technical, here is an article that explains it better than I could. With a leaf shutter, the image is exposed from the center out, eliminating this effect.

Of course, each of these benefits to a leaf shutter SLR is only evident if you have a need for very fast flash sync or capturing very fast things which is something the average casual photographer is unlikely to demand from their camera.

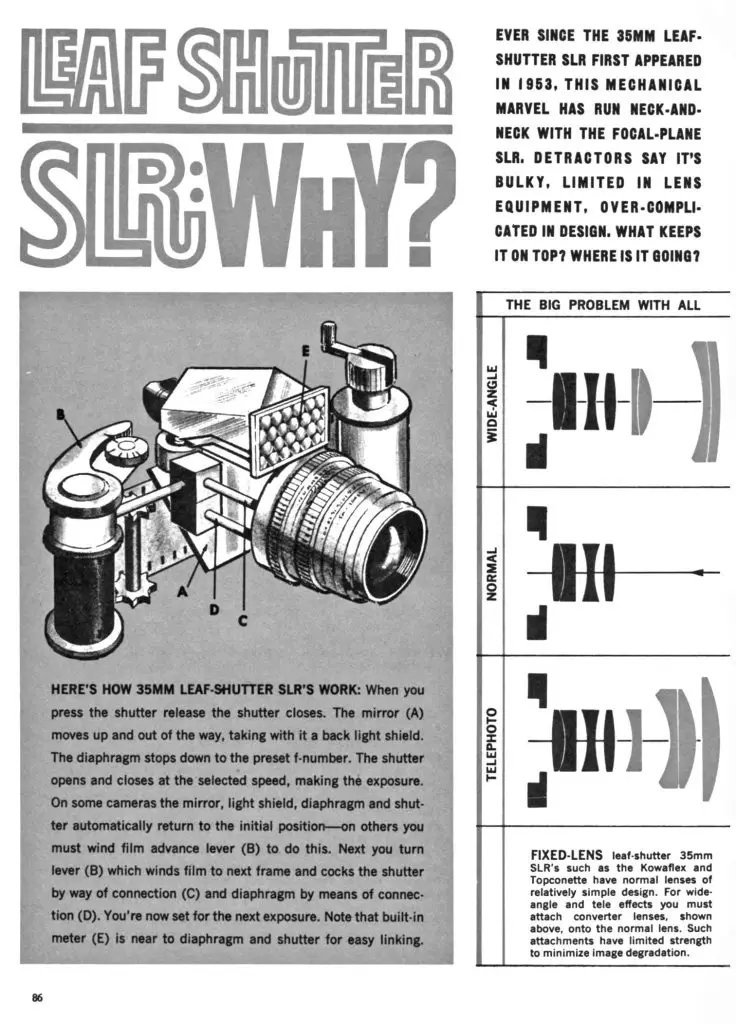

In January 1969, Popular Photography ran an article about Leaf Shutter Reflexes (LSRs) promoting the virtues of the leaf shutter including most of what I’ve already discussed above. Current models at the time of this article were the Kodak Retina Reflex S, III, and IV, Kodak Instamatic Reflex, the Topcon Auto 100, and the Voigtländer Bessamatic and Ultramatic but models by Kowa and Zeiss-Ikon are mentioned as well.

The article covers a couple other problems with LSRs such as their inability to closely focus, especially with telephoto lenses. The Kodak Retina Reflex’s Schneider Tele-Xenar 135mm lens has a close focus of 13 feet! Things aren’t quite so bad with other systems, as Topcon and Kowa 135mm lenses go down to about 6 feet.

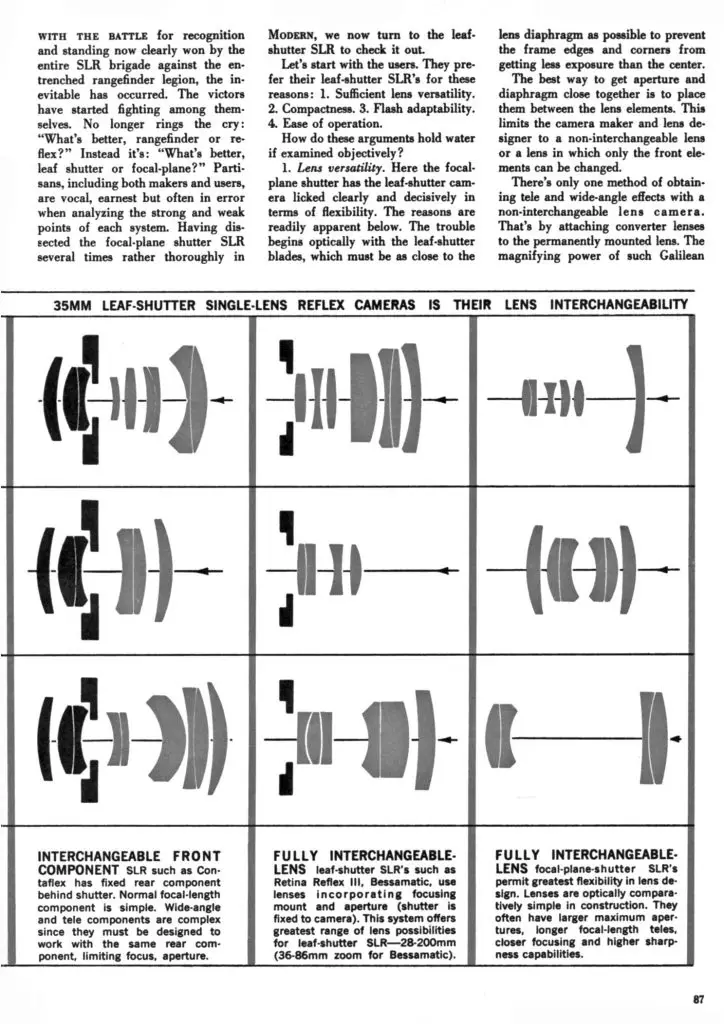

A bonus article from September 1962 further talks about the different styles of interchangeable lenses available on LSRs and what their limitations are. LSR cameras were physically limited to apertures no larger than f/1.8 and lenses no wider than 35mm due to the small maximum opening of the shutter itself.

The longer article from the January 1969 issue below in PDF format. As with all recent Keppler’s Vault articles, you may download this original PDF using the buttons at the bottom of the preview below.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2019.

Interesting summary of the pros and cons of the two basic SLR designs, Mike. I have a Fujicarex II which is closest to the SET-R in design: It includes a (sort of) instant return mirror in its operation sequence. The cacaphony of clanks and bangs it makes when fired is something to hear … not a street-shooter’s camera, that’s for sure! … You mention the “rolling effect” produced by focal plane shutters when either the camera or the subject is moving fast, transverse to the film plane. Have a look at some of the race car and horse images made during the 1930s and ’40s with Speed Graphics to see this effect. If I am not mistaken, DSLRs suffer a similar rolling problem at high shutter speeds, which is typically noticed in videos of aircraft propellers. The fast-spinning blades either appear to be curved, or to be completely detached from the propeller hub.

The Fujicarex II is a very neat camera and one that I not only have in the queue, but have recently shot and plan on getting a review of early next year!

Mike, I’ve long had a fondness for leaf shutter slr’s since acquiring my first, the original Kodak, cheaply from a local camera store and came “as is”. It worked fine for a while but then the mirror locked up. In those days I was more than happy to mess with cameras, but with this one I got hold of a copy of the service/repair manual and proceeded to strip it down. This really showed how complicated the workings were. I did manage to get it going but I suppose lacking the proper tools I was doing as much damage as I was correcting for and it got to the point of being a nice paperweight!

Undeterred, later I started to acquire some nice, late model, Contaflexes and a few Pro-Tessars. I have four now. All these still work well, the only failing is that on only one does the meter still function. I suspect that Zeiss thought of these as kid brother to Contarex in that they produced interchangeable film backs for them. How cool is that?

Later acquisitions are the Voigtlander Bessamatic II, aka de luxe (and which is my personal favourite by far) with Septon, Skoparex, Skopar-X and Dynarex, all in virtually mint condition, a Retina Reflex III + three lenses, an Agfa Colorflex, Rollei SL26, and the latest buy, a Topcon Wink Mirror S.

Agfa go to the expense of interchangeable v/f’s but then equip it with the three element Apotar. For such an otherwise excellent and well built camera, a Solinar at the very least would have been warranted. The little Rollei is quite a cutey with its chunky build and a bit of an eye opener with its large square v/f image. The difference in build quality of the Topcon is very noticeable and simply doesn’t compare with the German models. However, it came in very cheaply with a nice 35mm lens and duff meter. Otherwise, it is quite usable.

I never really started out specifically looking to collect leaf shutter SLRs, but a combination of them often having designs that are a lot more distinct than the hordes of generic Japanese focal plane shutter SLRs that were made over the years, plus the addicting sounds they make when the shutter fires (and works), they just seemed to flock to me. It sounds like you have had the same experience. I have many of the same models you do, including the Topcon Wink Mirror S, plus a few other interesting ones like the DeJur SR, Pentacon Pentina, and Nikkorex Auto 35 (none of these three work). I ALMOST had a chance to pick up a Royer Savoyflex but things didn’t work out. I still find them interesting, but my success rate with them is very low so I try not to seek them out anymore.

“Another benefit to leaf shutters, is that at their fastest speeds, they can introduce a rolling effect…” This is by no means a benefit, nor is it a property of leaf shutters, so this should really read, “Another detriment of focal plane shutters, is that at their fastest speeds, they can introduce a rolling effect in which the subject being photographed moves in the short period of time when the shutter first begins to open and when it completely closes… With a leaf shutter, the image is exposed from the center out, eliminating this effect.”

Also, the reason the last sentence is true is because a leaf shutter is not in the focal plane, so it acts as a second aperture, which can be a little odd when approaching the top shutter speed of a given camera (or lens in the case of lenses that contain the leaf shutter, as occurs in medium format cameras), because it will effectively pass through several different apertures as it opens and closes. This is explained well by the answers given by Olin Lathrop and also Roger Kreuger on the Photography StackExchange: https://photo.stackexchange.com/questions/84964/leaf-vs-focal-plane-shutter-is-there-is-difference-in-image-captured.