This is a Revere Eye-Matic EE 127, a fully automatic rangefinder camera that shoots square 4cm x 4cm images on 127 roll film. It was built by the Revere Camera Company of Chicago, IL, USA starting in 1958. This camera was one of the very first fully automatic “electric eye” cameras produced in 1958 which was the year that a huge number of other cameras with a similar feature set would make their debut. Unlike most other automatic cameras from 1958, the Revere also had a rangefinder for accurate focus. Over the years, the camera has developed a bit of a notorious reputation due to it’s very large and unique white body. Most collectors either love these cameras for it’s distinctiveness, or hate it due to it’s comically large size.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (twelve 4cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (twelve 4cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 58mm f/2.8 Wollensak Raptar coated 4-elements

Focus: Variable if SLR, 2.6 feet to Infinity with Click Stops for Portrait, Group, and Scenery

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Wollensak Leaf

Speeds: Single Speed, 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ viewfinder aperture readout and Programmed AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe with M-Sync and ASA port for X-Sync

Weight: 984 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/revere_eye-matic.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Revere Eye-Matic 127 is one of the strangest cameras ever made. It came in a large and heavy all white body and was made by a company that didn’t have a lot of experience making still cameras, yet it boasted a rather innovative feature set, combining automatic exposure, a coupled coincident image rangefinder, automatic film transport, and a quality 4-element Wollensak lens. The quality of images from this camera is superb, and with it’s large and bright viewfinder is very easy to use, but you can forget about being discreet with this camera as it’s big, bright, and loud! I love it! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for cool factor, one of the most distinct looking cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.1 | ||||||

History

The Revere Camera Company was originally founded in 1920 by a Russian immigrant named Samuel Briskin as the Excel Auto Radiator Company. Briskin was born in 1891 as Shulem Boriskin. A Russian Jew, Boriskin fled his home country due to anti-Semitic hostilities and wound up in Chicago in the early 20th century. Having little more than a 6th grade education by the age of 20, Boriskin was a hard working and determined man who learned a trade as a metal worker, and by the age of 30, he left his job at a Cedar Rapids based factory to start manufacturing automobile radiators back in Chicago.

He formed the Excel Auto Radiator Company in a small office at 1827 S. Michigan Avenue and through a combination of skill in metal fabricating and savvy salesmanship, he inked contracts with companies as big as Sears Roebuck & Co., Montgomery Ward, and Western Auto.

By 1930, Excel had expanded it’s operations to include plants in Oakland, Philadelphia, Dallas, and Kansas City. The Excel Auto Radiator Company continued to thrive throughout the Great Depression and by 1933, Sam Briskin was a self-made millionaire.

It is not completely clear what caused Briskin to take up camera manufacturing, but it is believed that due to his ties to Chicago businesses, he likely came across another Chicago based company, Bell & Howell, who was a very successful manufacturer of motion picture cameras and projectors. Bell & Howell’s most successful camera, the Model 2709 was very popular in Hollywood and it’s products were the standard to which other motion picture cameras were built. They were very good, but also very expensive, and it is thought that perhaps Briskin became interested in Bell & Howell’s business and thought he could “one up” them with a competing model, but at a lower cost.

Whatever the reason, Briskin saw enough promise making motion picture cameras, that in 1939, he completely reorganized his company as the Revere Camera Company. The company still manufactured automobile radiators, but it’s primary business was cameras.

The name Revere was chosen as an homage to the Excel Auto Radiator Company’s largest supplier of copper, which is an essential element in making radiators, the Revere Copper Company. Founded in 1801 by American patriot and silversmith, Paul Revere, the Revere Copper Company was the first successful copper rolling company in the United States. It mined copper and rolled it into thin sheets that were used in the construction of naval ships and other industrial applications.

In the early 20th century, the Revere Copper Company was a supplier to many manufacturing companies like the Excel Auto Radiator Company who needed copper. Being Excel’s biggest supplier, it is thought that Sam Briskin might have felt loyal to Revere, thus using their name for his new company.

Sam Briskin handed over the reigns of the newly created Revere Camera Company to his three sons, Phil, Ted, and Jack and with a only a 5% stake in the company, Sam Briskin functioned as company chairman.

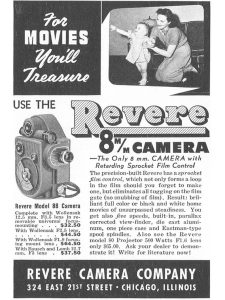

Less than a year into it’s operation, in 1940, Revere launched it’s first motion picture camera, the Revere 88. The new camera was a “double 8mm” design, similar to Bell & Howell’s Filmo Companion model. It was a compact, pocket sized camera that would shoot about 2 minutes worth of footage on half of a roll of 16mm film, at which time, you would open the camera, reverse the spools, and then shoot another 2 minutes on the other half.

The Revere 88 was feature for feature, almost identical to the Filmo Companion, and built to a similar high quality, but sold for $30, compared to the Bell & Howell which was priced at $50. Revere’s goal across the board was to compete with Bell & Howell in quality but at a lower cost.

Their plan worked, and Revere cameras quickly gained a reputation as a lower cost alternative to more expensive Bell & Howell and European cameras, and opened up the door to home videos for those who might not have been able to afford their own motion picture camera.

In 1942, shortly after the United State’s entry into World War II, Revere, like many American manufacturing companies, transitioned it’s production towards the war effort. Making military use cameras and other products, the company built up it’s work force and prepared for the day where it would resume producing consumer products. That day would come in 1948, when the US military would release Revere from it’s obligations, and Sam Briskin would immediately bring a lawsuit against Eastman Kodak, accusing them of monopolizing the 8mm film market, a case that would eventually be settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of money.

Strangely, in 1947, Sam Briskin’s middle son Teddy, became embroiled in the Hollywood lifestyle to which Revere often sold it’s products to, and he got engaged to singer and actress, Betty Hutton. Hutton not being of Jewish faith, caused a rift in the Briskin family, and shortly after their marriage in 1947, Teddy Briskin left Revere, and with his new bride by his side, decided to compete against Revere, opening his own motion picture camera company, called the Briskin Camera Company.

Briskin would launch a compact 8mm camera called the Briskin 8, that had an easy load magazine that initially saw moderate success, but by the early 1950s, failed to compete in the market both with Revere and Bell & Howell. A few short years later, the company went out of business and Briskin and Hutton’s marriage ended in divorce, causing Teddy Briskin to move back to Chicago, asking for his old job back.

It would seem that Teddy Briskin couldn’t shake the Hollywood lifestyle as in 1952 and in 1955 would marry, and divorce two more Hollywood actresses, Joan Dixon, and Colleen Miller. Teddy would be given a low level management job at Revere, reporting to his two other brothers, Phil and Jack.

By the early 1950s, Revere had a full lineup of motion picture cameras and projectors, all of which were lower cost alternatives to more expensive Bell & Howell products, but perhaps growing tired of having it’s products undercut by Revere, Bell & Howell eventually launched it’s own lower cost lineup of 8mm and 16mm cameras and projectors. Combining that with the fact that 8mm cameras were starting to fall out of favor with the public, by 1953 Revere made one last bold move to attempt to reignite their business, which was to buy the Wollensak Optical Company of Rochester, New York.

Wollensak was founded in 1899 by Andrew Wollensak, first making camera shutters, but then entire cameras and lenses. Wollensak lenses were used by a huge number of American camera companies, from Argus, Kodak, Detrola, Clarus, Ciro, and Revere. Using Wollensak’s positive reputation in the market place, in 1953, Revere would launch a new line up of premium motion picture cameras under the Wollensak name.

Despite premium packaging and some enhanced cosmetics, Revere’s Wollensak products were nearly identical to the company’s less expensive Revere branded products. This creative use of brand engineering was a mixed bag for Revere. Sales initially improved for the company, and it allowed Revere to experiment with new products.

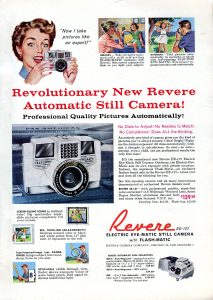

In 1958, Bell & Howell would release an all new “electric eye” still photo camera that used 127 format roll film, called the Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127. The new camera was released at a time when automatic exposure was an exciting new feature to be implemented into cameras as competing models from AGFA, Braun, and Kodak all entered the marketplace with this same feature. Perhaps wanting to stay on their competitor’s heels, Revere released their own “electric eye” 127 camera called the Revere Eye-Matic EE 127.

A very large and strange looking camera, the Eye-Matic 127 had a white painted die-cast metal body, and came with a 4-element Wollensak Raptar lens. Due to the rudimentary technology behind early auto exposure cameras, the shutter only offered a single speed and very little manual control. One way in which Revere’s new camera was superior to the Bell & Howell is that it had a coupled rangefinder in the viewfinder for precise focus.

Unlike Revere’s previous effort to undercut Bell & Howell’s prices, at $139.50 the Eye-Matic 127 was quite a bit more expensive than Bell & Howell model, which sold for only $75. At a price that when adjusted for inflation compares to $1225 today, the Revere Eye-Matic was quite an expensive camera, especially one made by an unproven still camera company with a state of the art new feature that likely wouldn’t have appealed to many people willing to spend over $1200 on a new camera.

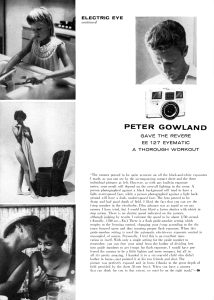

In the review to the right from the November 1959 issue of Popular Photography magazine, photographer Peter Gowland was impressed with how well the camera worked and it’s ease of use, saying that he handed the camera to a 6 year old child who didn’t even bother to focus, he simply pointed it at two of his friends and snapped away. When the photos were developed, the child’s photos all came out properly exposed and in focus. If that’s not a validation of the technology, I don’t know what is!

Despite positive reviews for the accuracy of it’s exposure meter and the quality of it’s Wollensak lens, the Revere Eye-Matic didn’t sell well. It is unknown how many were made, but I can’t imagine it was a lot.

By the early 1960s, the writing was on the wall for Revere. A combination of slowing sales and a terminal diagnosis of cancer, Sam Briskin sold the business to the 3M company, primarily so they could acquire the rights to a line up of magnetic tape recorders that Revere also produced.

Today, the Revere Eye-Matic 127 is pretty well known by collectors, mostly because of it’s extremely unique appearance. Some have even nicknamed it the “Storm Trooper” camera for it’s passing resemblance to the white shell of a Storm Trooper costume. It’s a cool camera for sure, but not worth very much. You can usually find these around the $25 price range online.

Repairs

The camera being reviewed in this article is the second Eye-Matic I’ve had. The first one not only had a dead meter, but I couldn’t get the shutter to consistently fire. No matter how much naphtha I poured in there, the shutter would only intermittently work.

Then one day, fellow collector Randy Reames contacted me and asked if I was interested in one and I took him on his offer. Originally the camera was a loaner, but after seeing the good results I got from it, Randy just said to keep it.

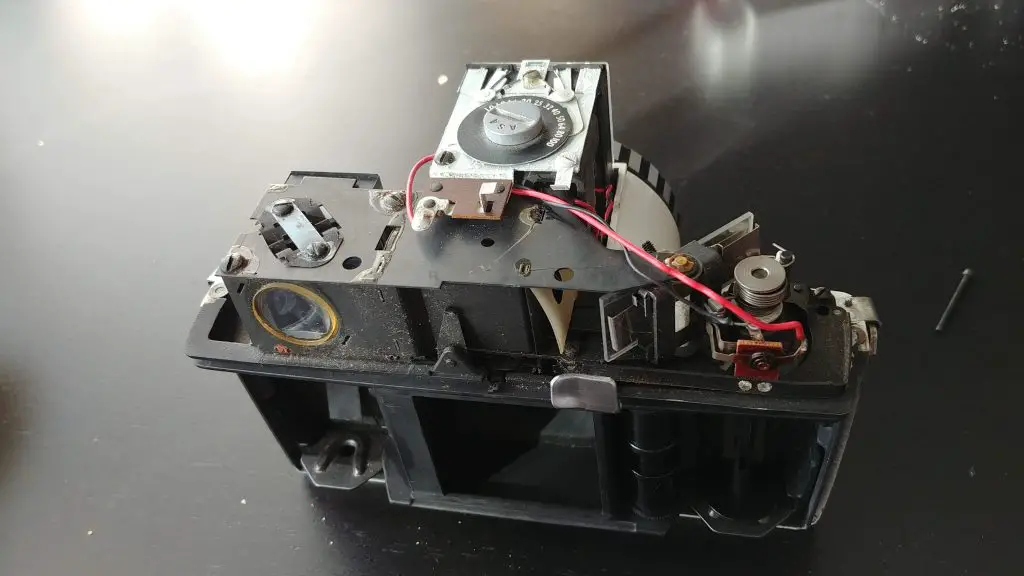

Randy’s camera had a working meter and shutter, but a dirty viewfinder and I wanted to open it up to clean it. Most cameras from the 1950s and 60s are pretty easy to open. Remove the wind lever and knobs, along with any screws you see on the top or side of the top plate and it comes off. Not with the Revere. At first, I couldn’t see any way to get it off as there’s no exterior screws anywhere. Then I took a look in the film compartment and saw two screws (indicated by yellow arrows) on each side of the compartment, pointing upward. Could these be it?

Yep. Remove these two long screws and the entire top plate lifts off. Despite the large size, there’s not much to this camera. Clean everything you see with some Q-tips and glass cleaner, and be sure to stay away from the beamsplitter and you’re good to go. The rangefinder on this example was correctly aligned, so I did not need to adjust it.

The innards of the Revere seem a bit haphazard, suggesting it was put together by people who likely didn’t have a lot of experience building still cameras. Notice the red wires for the meter loosely running around. Just be careful in here when cleaning and put it back together in the opposite of how you took it apart and you should be good to go.

My Thoughts

Picture a 1950s or 1960s Japanese rangefinder in your mind and I bet I can guess what it looks like. It’s got a chrome or silver body with black body covering. There’s probably a mostly flat top plate and rectangular body, right? The film advance lever, shutter release, and rewind knob are all in the same locations on them all. If it has a meter, its probably a small CdS sensor or selenium exposure meter either on the body, or around the lens.

Is what you’re picturing something like the image to the right? Me too!

The Japanese were adept at designing quality cameras, but they weren’t always the most creative when it came to the design of their cameras, so that’s why when you first see an American made 127 rangefinder camera like the Revere Eye-Matic 127, you’re a little shocked at it’s appearance. Is that even a camera you may ask?

Well, yes it is, and what a camera! Behind it’s ungainly appearance lies a pretty capable and surprisingly complex device. For starters, the camera has a combined image coupled rangefinder that when viewed through the camera’s HUGE viewfinder makes focus incredibly easy and predictable. The camera’s most notable feature though is the inclusion of fully automatic exposure, which in 1958 was big news.

The Revere Eye-Matic 127 was one of 6 auto exposure cameras released in 1958, and only one of two that used 127 format film. The camera had some other cool features too, such as an automatic film transport that didn’t require peep holes. Just load in a fresh roll of film and advance the film lever until it stops and you’re ready for your first picture, just like a Rolleiflex! The camera also supported full M and X flash synchronization through it’s “Flash-Matic” system, which although not a new feature in 1958, was still pretty modern to have.

The top plate of the camera is rather uneventful other than the ASA film speed indicator and what looks like one of those battery compartment covers that you use a coin to open. Except it’s not a battery compartment, it’s the dial for changing the ASA film speed setting for the meter. Possible ASA film speed settings are in the range from 10 – 100.

Below the ASA speed dial is flash connection for a proprietary M-class Revere flashgun that was available for the camera. Apparently when this camera was new, there was originally a cover on top of this connection point, which on this camera (and most I’ve seen) is missing. Had the cover been there, it was removed with a coin.

If there’s one angle that the Revere really shows how large it is, it’s from the side profile. It’s dimensions front to back are almost the same as it’s height, giving a nearly square profile. This is a large camera!

On the camera’s left side is an angled shutter release button that manages to be in a very natural and comfortable location. The shutter release has no provision for a shutter release cable, which isn’t needed since the camera lacks a Bulb mode or any slow shutter speeds. On the right is a second flash connection point for electronic X-sync flashes. Both sides the camera have permanently mounted neck strap loops for attaching the camera to a strap.

The bottom of the camera has the 1/4″ tripod socket and features an elegant brushed steel looking trim piece running the entire length of the camera. Although purely cosmetic, it breaks up the “sea of white” paint across the entire body of the camera, a nice touch that I wish was duplicated on the top.

At the base of the lens, visible from the bottom of the camera is a chrome lever which controls the iris. With it in the position next to a red dot, as seen in the image to the right, the camera is in full auto mode. The camera will choose an appropriate f/stop depending on light and whatever ASA film speed you have set. By moving the lever away from the red dot, you can manually select the f/stop. Strangely, your chosen f/stops is not displayed anywhere on the outside of the camera. The only place you can see what you’ve selected is from within the viewfinder.

The back of the camera has the large viewfinder opening, along with a small window for the automatic frame counter, and the film advance lever, all on an attractive, semi reflective trim piece, featuring the “Revere” name.

In the center of the rear film door is a circular lock that secures the door to the camera body. To open the film compartment, simply rotate this lock counterclockwise to unlock it, and clockwise when reinstalling it.

The rear film door is not hinged, and is completely removable. The bottom of the camera is not connected to the door, which means the camera can still sit upright on a table with the door off.

Unlike many other 127 roll film cameras film transport is from left to right. You’ll notice a thick spool to the right of the film gate with serrated teeth along it’s top and bottom edges. This spool is the “feeler” for the film transport and not only operates the automatic exposure counter, but also activates the automatic film transport stop that locks the film advance lever once you’ve reached the next exposure.

The film transport in the Revere is good enough to detect the movement of the film, but it cannot detect the starting position of the film like many 120 “Automat” cameras like the Rolleiflex can. In order to properly load film into the camera, you must first line up two arrows, or in the case of some ANSCO film, two fingers, with a yellow dot above the take up spool before closing the camera. A yellow and black sticker on the bottom of the film compartment reminds you to do this. Once the film is lined up, reattach the door and continue to advance the film until it reaches the number ‘1’ in the exposure counter.

Fun Fact: For those of you who like to cut down 120 roll film to “make” 127 films, you already know that the length of the cut down 120 film is longer than a 127 roll should be. The Revere’s film transport works great with longer rolls of 127, giving you more than 12 exposures per roll. The exposure counter will stop at 12, but you’ll be able to get at least another 4 extra images on a single roll!

The viewfinder, as you can clearly tell, is very large and very bright with a very contrasty and easy to see circular rangefinder patch. I have poor vision and use prescription glasses, so large and bright viewfinders are often a huge plus for me, so there’s a lot to like about the one on the Revere.

The main part of the viewfinder has non-parallax corrected projected frame lines indicating the 58mm frame, and a projected indicator of the camera’s selected aperture. It will display the selected aperture f/stop whether you are shooting the camera in Auto mode, or manually. In the image to the right, you can see it is set to f/5.6. In automatic mode, three lines will show up if the meter has determined there isn’t enough light to make an exposure.

The Revere Eye-Matic 127 is an interesting camera for sure. Crazy ergonomics, even crazier design, big viewfinder, and a rather sophisticated feature set abound, but what kinds of images does it make?

My Results

This being the second Revere 127 camera to come my way, I was a bit skeptical as to it’s working condition. It seemed to do everything it should, but having a limited supply of good 127 film, I didn’t want to waste a good roll, so for it’s first roll, I loaded in a heavily expired roll of Kodacolor II 127 into the Revere and took it out shooting.

Upon developing that roll, I was pleased to see some sharply composed images, but the film did not hold up well at all. I’ve actually had pretty decent luck with old Kodacolor II, having shot it in my Kodak Medalist, and Kodak Duo Six-20, but these images were underexposed and heavily degraded. In fact, after scanning them in, the color images were so bad, you couldn’t make much of the image out, so I decided to gray scale them in Photoshop and boost the contrast and clarity settings. Doing so returned some semblance of a usable image, at least good enough to confirm the camera was working.

Knowing that the camera was worthy of some better film, I loaded in a fresh roll of Kodak Ektar 100 that had been cut down to 127 size. I chose Ektar as it would be a pretty close match for the Revere’s single 1/100 shutter speed. Ektar 100 didn’t exist when 127 film was discontinued in 1995, so this would be an interesting combination of a film and camera that was never meant to be.

I don’t know why I’m always surprised every time I see results from a camera with a Wollensak lens. I’ve shot them in the Argoflex EF, Ciro-Flex Model D, ANSCO Automatic Reflex, Bolsey B2 and many others and the results are always good.

Revere’s acquisition of Wollensak in 1953 clearly paid off as they had access to quality optics like the Raptar here. The camera’s single 1/100 shutter speed and coated optics are a perfect match for Kodak Ektar 100, even though the the film didn’t exist prior to 2008, 50 years after the camera was made.

Center sharpness is superb, as is color transmission, but I did notice some strong vignetting on brightly lit outdoor scenes. You can see it in the image of the baseball field and storage locker shots in the gallery above. I find this a bit curious as most Raptars are 4-element lenses that should deliver pretty good coverage to the edges. It’s plausible that the Revere’s strangely shaped iris is the culprit here, but I lack the necessary optical knowledge to know for sure.

Getting a bokeh shot on an automatic camera with limited manual functionality is not easy so I don’t have much to say about out of focus details, but in the closeup examples of the flowers, backgrounds seemed to be soft without any distracting “soap bubbles” or other strong artifacts.

If you’re curious what a lens like this would look like on digital, I found a Flickr gallery by Matt’s Crazy Lens Adventures which shows this lens hacked off the Revere and attached to a Sony digital mirrorless camera. The sample pictures are quite stunning!

The Revere Eye-Matic 127 is a very difficult camera to rate. For one, it was very innovative when it was first released, it has a large and easy to use viewfinder and rangefinder, it has automatic film transport which was something that very few 127 cameras had, and it came with a highly capable lens. But boy is it heavy, and loud! You certainly wouldn’t want this hanging from your neck for any extended period of time, and the shutter is one of the loudest leaf shutters I’ve ever heard. Some leaf shutters are so quiet, it’s difficult to even know they fired. Not here. Each press of the shutter release makes me think that a cigar cutter is in there, ready to chop through the end of a stogie. I think if this camera had interchangeable lenses, I might have actually tried it with a cigar.

But therein lies the best part of the Revere. It’s not a camera that can easily be categorized. Even after using it, I have to keep asking myself “did I like this camera”? That’s not something I can say about a large number of anonymous Japanese rangefinders or early electronic SLRs from the 70s or 80s. The experience of using the Revere Eye-Matic EE 127 sticks with you for a while. So when it comes to a memorable camera that’s fun to use and makes great pics, the Revere Eye-Matic 127 is a winner in my book and I think it would be for you too!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://camerapedia.fandom.com/wiki/Revere_Eye-Matic_EE_127

http://quirkyguywithacamera.blogspot.com/2016/06/boxy-beasts-of-127-bell-and-howell.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20160316211654/http://www.junkstorecameras.com/revereeyematic.htm

https://basepath.com/ClassicCameras/grid.php?id=18000587&key=z4MLcd

Briskin was of major importance to the survuval and success of Nippon Kogaku. Liholm convinced him to test, then import the 13mm f1.9 Cine Nikkor. Revere sold 1000s of those little lenses and gave NK badly needed cash flow at a critical time in the company’s existance.

Wow! I would have never guessed that there was a Briskin/Nippon Kogaku connection! Very cool information, thanks for sharing, Wes!

That’s fascinating! What you wrote definitely piques my interest in this camera. I’ve added a link to this page to the list of 127-format cameras at 127film.blogspot.com – if you’d prefer that the link not be included, just let me know and I’ll take it down promptly.

127 Day (12/7 – please see https://127film.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_18.html) is coming up in a little over a month – that would be a fun occasion to play with this camera!

JM, feel free to link to my site all you want. In my early days of research, I used your site while researching several different 127 models! I’d consider it an honor!

I just came a across one in a box of auction cameras. Thanks. I had no idea about any of this. I’ll have to get some film.

Mike,

Awesome article. Just scored a couple of the Revere 127 EE’s and strarted cleaning. I believe that the beamsplitter you mentioned was something I messed with because the rangefinder became completely usless. I finally got the glass back seated well enough to have a decent working rangefinder but is still off a tad vertically. I have no clue how to adjust so it’s back together and ready for its first roll. Fingers crossed!

Cheers,

brad

Thanks for the feedback! The Revere’s are excellent shooters. Too bad about the rangefinders, those beamsplitters can be really fragile. Some can handle a cleaning, some (especially Yashica rangefinders) cannot. Good luck with yours, hope you get some good results!

Very informative article. I have a Revere Eye Matic EE 127 with an erratic film advance and it will not show frame numbers. Do you know of anyone who works on this camera?

Thanks for the comments. The Revere is a pretty simple camera and I doubt there’s any technicians that specialize in it, but that said, you could reach out to Frank Marshman and me might be able to take a look at it. Before you do that though, perhaps you already know this, but just in case you don’t, the frame counter will not work without film in it. Have you confirmed the numbers don’t change, even after loading in a roll of 127 film?