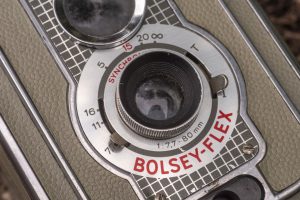

This is a Bolsey-Flex, a twin lens box camera produced by Ising of West Germany for the Bolsey Corp. of America around 1954. A couple of different cameras were produced for Bolsey, all with the same Bolseyflex name, but they were often made by different companies. This particular model is a name variant of the Ising Pucky II. It shoots 6cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. The Bolsey-Flex is an ornate, but simple camera that is often referred to as a “pseudo-TLR” as it resembles a regular TLR with a large waist level finder, but has the features of a box camera.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 80mm f/7.7 uncoated unknown elements (probably a doublet as the images are much sharper than a meniscus)

Focus: 5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Brilliant Waist Level Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: Timed and Instant (~1/50)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Flashbulb Sync

Weight: 695 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Bolsey-Flex is a nice looking, but simple twin lens box camera that is identical in function to the Ising Pucky II and Tower 120 Flash. It uses a bright and easy to use brilliant viewfinder and a focusing lens with adjustable f/stops which make it more capable than a simple box camera. With the right film and in the right light, the camera can make pretty nice shots that show strong vignetting giving the images a very vintage look. There is nothing special about this camera that would make me recommend it over similar cameras made by Argus or Kodak, but it is pretty. If you get a chance to shoot one, I recommend it, but I also wouldn’t seek one out either unless you just really like it’s design. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.8 | ||||||

History

The history of Bolsey cameras can be traced to a man named Yakov Bogopolsky, a Russian Jew born in Kiev in December 1895. Not much is known about Bogopolksy’s younger years, but we do know that he moved around a lot, and with each new location, he changed his name more than once.

The history of Bolsey cameras can be traced to a man named Yakov Bogopolsky, a Russian Jew born in Kiev in December 1895. Not much is known about Bogopolksy’s younger years, but we do know that he moved around a lot, and with each new location, he changed his name more than once.

At some point in his youth, he relocated to Switzerland and by 1914, had enrolled in college in Geneva to study medicine. Now known as Jacques Bolsky, he would eventually change his field of study to mechanical engineering and would show an interest in photography, namely motion picture cameras.

By 1923, Bolsky had designed his first 35mm cine camera, known as the Bol Cinegraphe which made it’s debut at the Swiss National Exhibition of Photography. The Bol Cinegraphe was unique in that it could be used both as a motion picture camera, but also a projector. The camera attracted enough attention that Bolsky had received financial backing from some bankers and a man named Charles Haccius, and formed his own company, simply known as Bol S.A.

Over the course of the next several years, Bolsky and Haccius would design a variety of cinema film cameras. Earlier models used 35mm film, but due to the rise in popularity of smaller film stocks, they would primarily create 16mm film cameras. One of the company’s first successes was the Bolex, a feature rich 16mm motion picture camera that had interchangeable lenses using the cine C-mount.

The Bolex was quite popular and sold well, and as a result would become the name of the company at some point in the 1920s. Bolex would design a variety of different 16mm and eventually 8mm variants of the Bolex, but would run into financial trouble around 1929. At this time, Bolsky would reach an agreement to merge with the Swiss company Ernest Paillard & Cie who made a variety of products like gramophones, typewriters, and music boxes. On September 30, 1930, Jacques Bolsky would sell a majority of his assets and patents to Paillard who would continue manufacturing Bolex cameras under the name Paillard-Bolex.

Bolsky would continue working as a chief designer for Paillard until around 1935 at which time he ventured out on his own. For a short while, he was employed by another Swiss watchmaker named Pignons S.A. and would once again design a new camera. This time, it would be a 35mm still picture camera which would eventually be known as the Alpa-Reflex.

The Alpa-Reflex was a hand made all metal single lens reflex camera that was aimed at the high end of the market to compete with top tier German marques like Leica and Contax. Alpa-Reflex cameras were hand made by technicians which resulted in very low production numbers. Alpa-Reflex cameras were expensive and rare back in the 1940s, and even more so today. On the used market an original Alpa-Reflex camera in good condition can fetch prices over several thousands of dollars.

Bolsky did not stick around with Pignons long, and in 1939, perhaps to flee anti-Jewish sentiment from nearby Nazi controlled Germany, Bolsky would relocate to the United States and once again change his name to Jacques Bolsey.

In 1941, Bolsey would form his first American company, Bolsey Laboratories, Inc. and would export Alpa models designed during his time working for Pignons, but would also design some of his own 16mm and 8mm motion picture cameras. Bolsey would primarily work in cooperation with the US military, designing a variety of fixed lens rangefinder cameras and motion picture cameras both for civilian and military use.

In 1947, Bolsey Laboratories, Inc. would reorganize and become the Bolsey Corporation of America. The first new model released under the new Bolsey name was called the Bolsey B. It was a metal bodied compact 35mm rangefinder camera that used a Wollensak Alphax shutter and a 44mm f/3.2 lens.

The Bolsey B would be the foundation for an entire B-series of cameras. The next model, and most successful, would be released in 1949 and would be known as the B2. The B2 is very easy to differentiate from the original B because it literally says “Bolsey B2” stamped in the metal fascia on the front of the camera.

The B2 would become the company’s best selling and most successful model, staying in production until 1956. Originally selling with a list price of $73.50, it was advertised as having the most features of any compact 35mm camera. Bolsey made every attempt to pack useful features like flash synchronization, double exposure prevention, a split image rangefinder, and a quality f/3.2 coated lens into a compact and light weight body.

Although primarily a 35mm only company, Bolsey did release a pair of “pseudo TLR” twin lens box cameras called the Bolsey-Flex and Bolseyflex. The first version with the hyphenated name was a rebadged Ising Pucky II, a camera from an obscure German company known more for making tripods. Although both cameras had nearly identical features and shared the same greenish-tan body covering, they had completely different designs. I am unsure of the non-hyphened Bolseyflex was also an Ising design, or built for Bolsey by someone else.

The Bolsey-Flex sold new in a kit with a flash, bulbs, batteries, and a leather-like vinyl case for $29.95 in the 1957 advertisement to the left from Rohde-Spencer Company in Chicago, IL. This price, when adjusted for inflation compares to about $280 today, making it an affordable kit for the amateur.

There is no way to know how successful of a camera either version of the Bolsey-Flex was. On one hand, this style of twin lens box camera was very prevalent in the 1950s with similar designs by Kodak, Argus, and a number of other companies available, on the other, the fact that there were two of them suggest it sold well enough to keep being produced.

In 1956, the Bolsey company’s assets and patents would be sold to (you guessed it) another watchmaker named Wittnauer. After being sold by Wittnauer, the B2 would continue to be made except it would be rebranded as the Bolsey Jubilee. The Jubilee would replace the Wollensak lens and shutter with ones made by Steinheil and Gauthier respectively. The shutter release would also be moved to the top plate of the camera.

I could not find a whole lot of information about what Jacques Bolsey did after the sale of his company to Wittnauer in 1956, or even why he did it, but it seems that he was still involved in cinema camera design as recently as 1960 although I don’t believe he had his own company anymore. Maybe he worked as a freelance designer for other companies. The only conclusive information I can find about him is that he would pass away in December 1961, at the age of 66.

Today, the Bolsey B2 is still pretty easy to find on the used market, but the rest of their models like the Bolsey-Flex aren’t. The B2 has a unique look and design, so they are still pretty popular with collectors. While I don’t think there are many people who will pay a high sum for one, in my time talking to other collectors, it seems that everyone has or has had at least one in their collection at some point.

My Thoughts

I picked up this Bolsey-Flex in the same lot where I got my Alpa Alnea 7 which is fitting because despite both models being on complete opposite ends of the camera price scale, both were also products of Jacques Bolsey. It would seem that the original owner of both cameras really liked this man’s products.

The Bolsey-Flex is a very simple camera that shares a lot in common with other twin lens box cameras like the Vogitländer Brillant and the Argus Seventy-Five. Although it looks like a standard TLR camera, it actually shares more in common with a simple box camera like a Kodak Brownie as the viewfinder is just a simple lens that is not coupled to the taking lens. That means that the view through the viewfinder is only an approximation of what you will see and will not reflect the set focus distance.

The camera is made mostly of metal, rather than plastic like some less expensive models, giving it a bit of heft. Weighing in at 695 grams (1.53 lbs) the camera is not lightweight, and likely would cause some strain if left hanging from a neck strap for extended periods of time. The body covering is an interesting color that seems to vary depending on how the camera was stored. My example has a beige color, almost like khaki pants, but I’ve seen many examples of this camera where it seems to take on a lime green color, almost like mint ice cream. I think the beige color is correct, but a combination of staining from UV light and possibly the type of lighting in which the camera is photographed in, can affect the tint.

The shutter on the Bolsey-Flex is very simple with only two settings, Timed (which is more like Bulb) and Instant, which I estimate to be around 1/50 of a second. There is no iris for stopping down the lens, but there is an adjustable plate with three different sized holes which act as f/stops f/7.7 through f/16. Unlike the most basic box cameras however, the Bolsey-Flex can be focused from 5 meters to infinity, giving it a step up from the simplest of cameras.

The Bolsey-Flex is a rebadged Ising Pucky II which is only different from the Pucky I in that it has a cover over the domed “brilliant” viewfinder on the top of the camera, which the Bolsey-Flex has. A simple flip of the lid reveals a large and very bright viewfinder that allows you to get an approximation of what will be captured on film. Since it is not coupled to the taking lens, everything you see looks to be in focus, but that is not what will be captured on film.

To the right of the viewfinder hood is the cable threaded shutter release which is conveniently located where your thumb would be whole holding the camera at waist level. The Bolsey-Flex does have a double exposure prevention feature which locks the shutter release until you advance the film again.

The back of the camera has a simple red window with a sliding door to protect it from excess light. Whatever red material the see through window is made of, seems to have done a good job of retaining a dark red hue which gives me confidence that it should not allow light leaks in, which is common in older cameras where the red window can lighten or yellow over time. I still would caution against extra sensitive films however unless you plan on shielding the red window from excess light while advancing the film.

Opening the back of the camera requires a twist of a locking knob on the camera’s left side. Turning this knob clockwise allows the entire back and most of the sides to swing down revealing the film compartment.

The film compartment of the Bolsey-Flex looks familiar to anyone who has used a Twin Lens Reflex camera in that the supply spool goes on the bottom, across the film plane and two sets of rollers, and then onto a take up spool on the top. Most of the time, cameras like this are found with an empty spool in the supply side, so you’ll need to move that to the take up side first, before you can spool a new roll of film.

One nice thing about the design of the rear film door is that the seams wrap around to the sides, which offer additional protection from light leaks than some other cameras of this style where the door seams are near the very edge of the film plane. After looking at my first roll from the Bolsey-Flex, I had no issues with light leaks because of this.

The bottom of the camera has a slightly elevated 1/4″ tripod socket and two small feet near the back corners to allow for the camera to sit level on a flat surface, without interfering with the bottom film hinge.

The view through the viewfinder is bright and easy to see, but it must be kept at waist level. Trying to bring it closer to your eye reduces the image to a small circle which does not accurately reflect the image that will be captured on film. This could be an issue for people with poor vision as there’s no magnifying glass like that of regular TLRs.

The Bolsey-Flex is a solidly built, all metal twin lens box camera with a basic feature set, but just enough features to make it a little more capable than a simple Kodak Brownie. With a full focus capability and features such as an adjustable aperture, cable threaded shutter release, flash synchronization and double exposure prevention, the camera was a capable camera for the amateur.

But how capable, exactly?

My Results

When cameras like the Bolsey-Flex were first sold, they were designed for slower speed films like Kodachrome and AGFA Pan 25, so when shooting them today, it’s important to keep that in mind when selecting a film to load into them.

I didn’t do that, and instead loaded in a fresh roll of Kodak Portra 160 which although a faster film than would have ever been shot in this camera in the 1950s, has proven itself to have an incredible amount of latitude, so I figured what the heck! The Bolsey-Flex has a single shutter speed of around 1/50 but three aperture settings, so as long as I stayed out of direct sunlight and used the smaller openings, I figured I’d be fine.

Despite being a rather simple camera, I expected to see some pretty decent images from it. I’ve been impressed with other “twin lens box cameras” like this before so I had hoped to see sharp images with good but not great corner to corner sharpness and faithful colors.

Upon scanning in the negatives, I saw most everything I expected to see with the exception of some really strong vignetting near the corners on some of the images. The amount of vignetting varied a bit depending on how closely I focused. The one of the little boy and the white and yellow flowers was by far the worst and these were both close focus shots. These images look almost as if they were shot using a crop sensor lens on a full frame SLR. I wonder if the act of moving the lens farther away from the film plane increases the vignetting.

To be honest, I kind of liked the effect as it gave the images from the Bolsey-Flex a look that you can’t easily achieve on other medium format cameras, but I have to wonder what other people using this camera as their primary photographic tool might have thought. While this camera is over 65 years old, it seemed to be in good operating condition, so I can’t see any issues that would have caused this, so I can only assume this is just how this camera is.

Overall though, the images were predictably sharp in the center, and despite the simple lens recreated the slightly pastel palette I usually see with Portra 160 color film. It’s also good to see that the relatively fast speed of Portra 160 was good match for the single shutter speed. I wonder though how slower film would have fared. Would it have shown such strong vignetting?

I only shot a single roll of film through the camera, and while I was happy with the images I got from it, there was nothing about them or the experience of using the Bolsey-Flex that I haven’t seen or experienced with much more common cameras like the Argus Seventy Five, or some of Kodak’s many simple twin lens Brownies.

The Bolsey-Flex has an attractive appearance which may appeal to some collectors, but as a shooter, I feel as though there’s better options that are also much easier to find.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Bolsey-Flex

https://www.photothinking.com/2021-02-19-bolseyflex-not-much-flex/

http://westfordcomp.com/classics/bolseyflex/index.htm

http://www.tlr66.com/abcde/bolseyflex.php (in Japanese)

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-4984-Bolsey_Bolsey-Flex.html

Mike, a very pretty camera in this trim, and IMO better looking than the later Mk.II. With the optical quality at hand, and being it’s an f7.7 I believe we can be very confident in saying the lens is an achromat. This is surely borne out by your images, particularly the main one extreme bottom left and which viewed at 3000×3000 is pretty damn good.

That would be my guess too. I was surprised that I could not find any reference anywhere to the make up of this lens. Even on the most basic of cameras, you can usually find some info about the lens. Names like “Doublar” or curved film planes usually offer you some clue to the lens design, but with the Bolsey-Flex and the original Ising, there just is no info and I didn’t want to take it apart to find out!

Destroy that lovely camera? Definitely not! I suspect many German optics companies provided “un-named” lenses for many cameras in the lower price bracket, given the number of camera manufacturers who clearly would not be making their own lenses. Some “branded” ones do exist, such as the Goerz “Frontar” used on some Zeiss Tengors, for example.

I have a Tengor 56/2 with the Frontar and which I’ve still to put a test film through. It’s 21/4 x 31/4 inches, so could be fun!