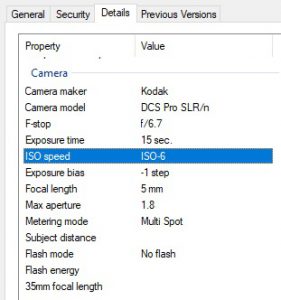

This is a Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n, a digital SLR camera produced in cooperation with Nikon and Kodak starting in 2004. This camera was part of Kodak’s Professional lineup of DSLRs and is notable as being Nikon and Kodak’s first digital camera with a “full frame” 24mm x 36mm sensor. Using Nikon’s F-mount means that the DCS Pro SLR/n could accept nearly the entire lineup of Nikon F-mount lenses, including AF, AF-S, and G lenses at their intended focal lengths without any crop factor. The camera’s 13.5 megapixel CMOS sensor lacks an anti-aliasing filter which improves edge sharpness at the expense of displaying moiré artifacts. Another feature of this camera that sets it apart from DSLRs produced today, is that it supports exposures with an ASA speed of down to 6 for extremely low noise images that were ideal for product photography. A very similar camera called the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/c also existed, but it was built on a Sigma SLR chassis with a Canon EOS lens mount.

Sensor Type: 13.5 Megapixels Full Frame 24mm x 36mm CMOS

Sensor Type: 13.5 Megapixels Full Frame 24mm x 36mm CMOS

Storage: 1x Type II CF+ compatible CF card, 1x SD/MMC card

File System: DCR (RAW), JPG, DCR + JPG

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 AF Nikkor coated 6-elements + others

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet

Focus: In-Body Focus Motor Supports Nikkor AF and AF-S lenses

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with electronic 5-point focus detect, and full information LED display

Shutter: Electronically controlled, vertically traveling focal plane shutter

Speeds (Normal): B, 2 – 1/4000 seconds, step less in AE modes

Speeds (Long Exposure Mode): 2 – 60 seconds with ISO 6 – 50

Exposure Meter: TTL 3D Matrix, Center-Weighted, Spot, with Programmed, Av, Sv, and Manual modes

Sensitivity: ISO 160 – 800, 1600 boosted, ISO 6 – 50 (long exposure mode only)

Battery: Kodak Professional DCS Pro Rechargeable Lithium Battery Pack

Flash Mount: Nikon Speedlite Hot Shoe, 1/125 second X-sync

Weight: 1203 grams (w/ battery and lens), 1039 grams (battery only), 924 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/KodakDCSProNManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n was both Kodak’s last attempt at a professional digital camera and the first ever full frame digital sensor to appear in a Nikon body. The camera has most of the modern conveniences of DSLRs today and generally good ergonomics, but it is large and heavy. The full frame sensor can produce excellent images if you use it to it’s strengths which is well lit outdoor scenes or studio photography. Slow operation, unfamiliar menus, a limited ISO range and the fact that this is a 16 year old digital cameras with 16 year old batteries makes this a camera that’s not very dependable for every day use as there are far more better examples that are faster, make higher quality images, and more dependable batteries. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance and exceptional photo quality both then and now | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.0 | ||||||

History

In various articles covering the history and eventual demise of the Eastman Kodak Company, it is easy to think of them as a film only company who ignored the age of the digital camera until it was too late. Sure, there were a great number of inexpensive Kodak point and shoot digital cameras in the 2000s, but they never sold in the same numbers as those by Nikon, Canon, Sony, or Fuji.

And while it’s true that Kodak did not properly embrace digital photography the same way these other companies did, it is incorrect to say that Kodak simply ignored it. In fact, in December 1975, at the age of 24 and while working for Kodak, a man named Steve Sasson created the world’s first digital camera.

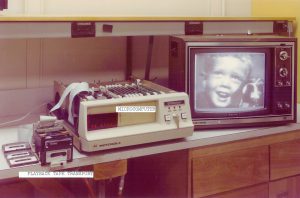

Like many pioneering designs, the first digital camera barely resembles anything of what we would today call a camera, but all of the necessary parts were there. It has a lens from some random Super 8mm camera, a parts-bin CCD image sensor, a digital to analog converter from a digital voltmeter, rechargeable nickel cadmium batteries for a power source, and an audio cassette recorder for storage.

Cobbled together in a basement lab using various circuit boards designed for other applications and a custom built aluminum chassis, Steve Sasson’s contraption captured a 0.01 megapixel black and white image, and wrote it to a run of the mill audio cassette tape. The entire image was captured in 50 milliseconds, but it would take 23 seconds for the image to be recorded to the tape. In order for it to be played back, it had to be read by a specially designed Motorola microcomputer and displayed on a television screen.

Steve Sasson would take his device and demo it multiple times to various executives at Kodak. After showing it off in one board room, he would be asked to show it off again to more executives, working his way up the chain to the highest ranking people working for Kodak at the time.

Both to Kodak’s credit and detriment, Kodak realized the potential of such a device. Here was something that could electronically capture images and play them back using no consumables, no film and no paper. The possibilities would be endless, so Kodak did the the most logical thing they could do with such a device…and hid it from the world to see.

Realizing that a digital camera system could spell the end for the film industry, Kodak knew that if the digital camera were to be mass produced, it would cannibalize the very market that Kodak depended on. The photography industry never made huge profits from the sales of cameras, the biggest profits were from the recurring sale of film and photographic paper. This new device would change all of that.

Over the course of the next 15 or so years, there were a few advancements in the world of digital photography, but most of them like the Sony Mavica used video based recording systems that would capture and digitize a single still image using NTSC or PAL video. Other companies like Canon, Toshiba, and even Nikon would dabble into the still video camera business, but none were considered true digital cameras as they used freeze frames of existing video standards as their method for capturing data. It wouldn’t be until the late 1980s before any new advancements would come that could actually be considered true digital photography, and once again, it would be Kodak who led the charge.

In 1987, Kodak would create the first solid state digital SLR camera that could capture megapixel images in a digital format. The Kodak Electro-Optic Digital Camera was designed in cooperation with the US Government as a way to capture digital images directly onto a magnetic storage medium. This camera used the body of a Canon New F1 film SLR and had a custom back with a 1.4 megapixel sensor, capable of 1340 x 1037 pixel images. The camera stored it’s images on a proprietary magnetic tape drive which was connected to the back of the camera using a ribbon cable. This camera was never sold the public and was created as a one off device. According to Jim McGarvey who was the lead designer of the Electro-Optic Digital Camera, only one was made and after delivering it, it was never seen again. Whether this camera still exists today in some closet of a secret government facility is anyone’s guess.

In 1989, it would be Steve Sasson again who would build the world’s first DSLR using a modern SLR body that wrote digitally compressed images to on board memory storage. The Kodak Ecam used a 1.2 megapixel sensor and was built into an entirely portable body that did not require a large storage device to be connected to the camera for it to work. Once again, Steve Sasson would demonstrate his new camera to the executives at Kodak, and once again, their reception was lukewarm.

Kodak would actually own patents for the name “digicam” and many of the technologies used in these early digital cameras. They would receive royalties by other companies for each new model made, and throughout the 1990s, would work in cooperation with other companies like Nikon and Canon building professional level digital SLRs, yet despite having a leg up on the entire world in the digital camera industry, Kodak failed to really embrace the technology, perhaps out of fear of cannibalizing the film market. A mistake that would ultimately lead to the company’s demise.

Throughout the 1990s, Kodak would release many commercially available digital cameras based off SLR bodies made by Nikon and Canon. The first was the DCS-100 from 1991 which used a heavily modified Nikon F3, and sold for the price of $30,000. It required the use of a shoulder mounted Data Storage Unit that contained a 200 MB hard drive and the power supply for the camera. While large and extremely expensive, the DCS-100 was a moderate success, selling nearly 1000 units, primarily to photojournalists who prioritized speed over quality. For the first time ever, an image could be captured in a remote location and electronically transferred back to the studio within minutes.

The Kodak DCS-200 followed in 1992 and was based off the Nikon N8080 film camera with digital electronics fitted to the back. Although it only offered a modest upgrade to a 1.5 megapixel sensor, it’s biggest advantage was that the body of the camera contained an 80 MB hard drive for local storage without the use of an external data storage unit. Although the capacity was less, it allowed for more freedom to use the camera without lugging around the storage unit.

As the 90s continued, new models would be released regularly with new advancements in speed and quality. Kodak was not only the market leader, but they had a near monopoly on the market as they owned the rights to many of the technologies in these cameras. Any attempts to compete in this market would produce profits for Kodak.

Most of Kodak’s digital cameras in the 1990s and early 2000s were part of their Kodak Professional DCS series. As the name implies, these cameras were marketed towards professional photographers who could shoot film on location and depending on the technology used, electronically transmit their images back to their home location without having to wait for film to be developed.

By 2002, digital photography was no longer a fringe technology and had been embraced by professionals for nearly a decade. New models were being created by every major camera manufacturer and semi-professional photographers all over the world were hanging up their 35mm and medium format film cameras for a new digital model. The end was near for Kodak’s Professional DCS series as the lineup had yet to turn a profit, but they had one more trick up their sleeve.

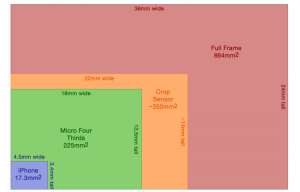

Until this point, all digital cameras, whether an SLR style or point and shoot used some type of CCD or CMOS sensor that was physically smaller than that of a normal 24mm x 36mm film exposure. This means that while many of these cameras used bodies with lens mounts that were compatible with lenses built for their film counter parts, using them on the digital variants meant that the focal length of the lens would change due to something called the crop factor.

In simple terms, imagine taking an image shot on a normal 35mm film camera, and then scan that image into your PC, and using software, crop out the edges, only saving the middle part of the image, then upscale that image back to the same dimensions as the original image. The physical number of pixels in your digital image is the same, but you have a “cropped” version of the original image. This is essentially the same thing that happens when you attach a lens like a 50mm Nikkor from a Nikon F3 onto a crop sensor digital camera with a Nikon F-mount.

As digital sensor technology improved, the idea of using a sensor that was the same size of a “full frame” 35mm negative became popular. The first full frame DSLR was released in early 2002 as the Contax N Digital, featuring a six megapixel 24mm x 36mm sensor produced by Philips. The camera was not successful as the sensor produced noisy images that were of lower quality compared to other DSLRs of the time, and the camera’s N-mount had only a small handful of lenses available for it.

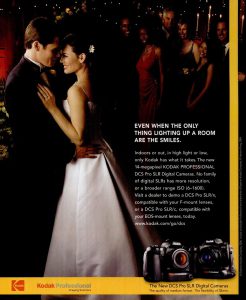

Later that year, Canon made a bigger step with the release of the Canon EOS-1Ds, a full frame 11.1 megapixel camera supporting Canon’s already well established EOS lineup of lenses. The EOS-1Ds not only had a higher resolution sensor, but it’s performance was excellent. In their review of the camera, dpreview.com gave the camera a Highly Recommended rating, saying that the image quality was best in class, and the best they’ve ever seen. The only caveat, was that the camera was very expensive, selling for $7999 body only, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $11,400 today making it entirely out of reach from all but professional photographers with deep pockets.

Canon’s limelight would only last a couple of months as on September 24, 2002 at Photokina, Kodak and Nikon together stole the show with the announcement of the Kodak Professional DCS Pro 14n, Kodak’s first full frame digital camera, and the first in a Nikon body. The DCS Pro 14n would not only top the Canon EOS-1Ds pixel count with a 13.5 megapixel sensor, but would also cost substantially less, with a retail price of $4995.

The DCS Pro 14n would go on sale in March 2003, and with a price more in line with what a professional photographer might pay for a crop sensor DSLR, they could now have one of the highest resolution digital cameras available, and with full support for Nikon’s entire lens library, at a price nearly half that of Canon’s model from the year before.

Although the DCS Pro 14n saw some success, it had disappointing low light performance, with noticeable digital noise at ISOs above 160. Digital noise wasn’t unusual for early digital cameras, but for a prestige camera like this, people expected more. Thankfully, Kodak quickly resolved the problem with an updated camera called the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n with an improved X14 imaging chip that improved noise while retaining all of the same features of the 14n. They even offered an upgrade path for existing users who wanted to get the new imager installed into their 14n.

Although the DCS Pro 14n saw some success, it had disappointing low light performance, with noticeable digital noise at ISOs above 160. Digital noise wasn’t unusual for early digital cameras, but for a prestige camera like this, people expected more. Thankfully, Kodak quickly resolved the problem with an updated camera called the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n with an improved X14 imaging chip that improved noise while retaining all of the same features of the 14n. They even offered an upgrade path for existing users who wanted to get the new imager installed into their 14n.

The DCS Pro SLR/n sold for the same $4995 price as the 14n which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $6750 today. In what was likely an attempt to further steal Canon’s thunder, Kodak would release a variant of this camera with all the same features, but built using a Sigma body with a Canon EOS lens mount as the Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/c. Sadly, despite a positive reception by professional photographers, Kodak’s DSLR business had never turned a profit and in 2005, would exit the digital SLR business, making the DCS Pro SLR/n and SLR/c their last digital SLRs.

Today, Nikon is still a leader in the professional and amateur digital camera markets with their DSLR and digital mirrorless models. Although Kodak would bow out of the DSLR market, Nikon would continue to improve their own designs all the way up to current models. Exactly how much of Kodak’s influence helped Nikon develop so many different successful models is not clear, but it had to have helped.

It might seem strange to some, but there is a collector’s market for early digital cameras, especially full frame models like the DCS Pro SLR/n. A combination of historical significance and the challenge of using outdated technology is appealing to some. The biggest issue however, is that unlike mechanical film cameras of the last century that usually still work, the electronics in early digital cameras is prone to failure, plus there’s the challenge of finding good working batteries, many of which have been discontinued.

My Thoughts

My first “vintage” digital camera review on this site was for the Fujifilm Finepix S1 Pro from 2000. When that camera was first released, it was considered to have cutting edge technology and features that cost quite a lot of money. In that review, I was surprised at the quality of images I got from it. Sure, the camera’s sensor was only 3 megapixels, but considering how often digital images today are scaled down and shared on social media or viewed on tiny smartphone screens, a 3 megapixel image can still look quite good.

My first “vintage” digital camera review on this site was for the Fujifilm Finepix S1 Pro from 2000. When that camera was first released, it was considered to have cutting edge technology and features that cost quite a lot of money. In that review, I was surprised at the quality of images I got from it. Sure, the camera’s sensor was only 3 megapixels, but considering how often digital images today are scaled down and shared on social media or viewed on tiny smartphone screens, a 3 megapixel image can still look quite good.

That camera was like many DSLRs of the day in which a film camera is hacked apart and put back together with with digital parts. In this case, a Nikon N60 provided the basic chassis of the camera, shutter, and top plate controls. Fuji handled the digital sensor, back, bottom, and power supply for the digital parts of the camera. It required seven (7!) different batteries to work, two 3V CR123A Silver-Oxide cells in the hand grip to power the Nikon part of the camera, four 1.5v AA alkaline or NiMH batteries to power the Fujifilm digital parts, and a CR2025 button cell to maintain the camera’s memory. There were three LCD screens, one on the top plate that shows basic camera controls, a 2.0″ color LCD screen used to review images stored on the camera’s memory card and control some of the digital sensor’s settings, and a monochrome LCD panel with an orange back light that shows information like how many exposures are left on the memory card, your selected ISO setting, and other things.

It was clear that this camera was equal parts film and digital camera, and that in order for Fujifilm to make this camera, certain compromises had to be made to graft it’s parts onto the back of a Nikon film camera. These compromises are clunky and definitely require a bit of familiarizing yourself with before using the camera, but otherwise don’t affect the process of making photographs, at least not until you put the camera up to your eye.

The Nikon N60 which this camera is based on has a viewfinder that is designed to frame a normal 24mm x 36mm film image. The mirror, pentaprism, and viewfinder are all designed with this size in mind, except the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro does not have a digital sensor that can capture a 24mm x 36mm image. The sensor is physically smaller and is what we would call today a “crop sensor” because the captured image is smaller than that of a full frame film image.

Although the camera supported Nikon’s F-mount and all the same lenses the N60 would have, mounting one of those lenses to the camera would produce image that look zoomed in, or cropped from what you would have seen on a film camera. This issue with smaller digital sensors would later require new lenses to be build for digital SLRs that correctly frame the image into the smaller sensor. In Nikon-speak, crop sensor lenses are called “DX” lenses. You could still use a non-DX lens, but the captured image would be cropped at an approximate 1.5:1 ratio, meaning a 50mm lens would produce a 75mm image.

In a normal purpose built crop sensor DSLR, the viewfinder would be adapted to correctly display the already cropped image in the same space that a full frame image would have otherwise occupied. But not the Fujifilm FinePix S1 Pro as Nikon took a simpler approach and added a matte over the 24mm x 36mm image to show the cropped image. This results in a smaller viewfinder in which only the cropped center is shown. It’s certainly not a deal breaker, but was something that surprised me the first time I shot with the camera as I was used to seeing a much larger image from my DSLRs.

In these early days, DSLRs were very expensive and the only people buying them were early adopters who understood the idea of a crop sensor, and could shoot photography with lenses that would produce a different focal length than on a film camera, and with viewfinders that were smaller than they were used to. Early adopters are typically more forgiving than the general consumer and it was clear that if DSLRs were to reach wide spread acceptance, these compromises had to be eliminated.

At first, purpose built crop sensor cameras started to hit the market in which the viewfinder correctly showed a “full” cropped image without a matte. Nikon, Canon, and other companies worked quickly to release crop sensor lenses which could be used on these cameras at their correct focal lengths, but in 2002 the idea that simply making a full frame digital sensor was a better alternative to the crop problem. Not only would a full frame digital sensor solve the crop problem, but the increase in physical size of the sensor would mean that it could have more pixels and therefore make higher resolution images.

Without getting into a pointless debate about which is better between full frame and crop sensor digital cameras, my opinion is that image quality is not enough of a deciding factor to make up for the price difference. This is why when it came time to replace my aging Nikon D7000, I went with the Fujifilm X-T20 mirrorless. With a mirrorless system, I could adapt nearly every vintage lens ever made onto the camera using an adapter, something that wasn’t as easy to do with the D7000.

Still, having to deal with the crop factor in my current camera made me really excited to try out this Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n. Sure, it was 16 years old and finding a good battery for it likely would be a challenge, and who knows what kinds of compatibility problems I’d run reading the memory cards from it on my Windows 10 PC, and there’s always that risk of electronic cameras not aging as well as mechanical cameras, and well, I guess I almost talked myself out of picking one, but thankfully I didn’t.

The DCS Pro SLR/n is based off the Nikon N80 which I’ve reviewed before, but make no mistake, this is a big camera. The larger battery compartment grafted on the bottom is like a permanently attached accessory motor drive. There is even an auxiliary shutter release on the bottom corner for use when holding the camera vertically.

With the camera’s large size comes a lot of weight. In a shooting configuration with the Nikkor AF 50mm f/1.8 lens mounted and a battery in the camera, the total package weighs 1203 grams or 2.65 lbs making it the heaviest 35mm “style” camera I own. Considering the N80 this camera was built off already had a lot of plastic in it, I can’t imagine if a camera like this was built in the era of all metal cameras.

Helping somewhat to offset the camera’s heft is a generously sized right hand grip which is as deep as the original found on the N80, but longer to match the increased height of the camera. Also included on mine is a large, padded wrist strap that comfortably wraps around your right wrist allowing you to securely hold the camera one handed. This of course negates the secondary shutter release as you’d have to slip your hand out in order to use it, but with a secure grip on the camera, rotating it 90 degrees while still using the top plate shutter release is no problem.

The experience of using the camera is surprisingly modern. Other than the increased size, I felt right at home compared to my old D7000.

All of the controls were exactly where you’d expect them to be on a Nikon DSLR. The shutter release and power switch are in a comfortable position above the right hand grip. There are both front and rear control dials for controlling various functions of the camera. Beneath the shutter release are dedicated buttons for +/- EV compensation and flash compensation.

On the left side of the top plate is a PSAM mode selector with a dedicated mode for setting ISO. Beneath it is the drive mode selector for single or continuous shots plus a self-timer. Although not often found on professional level cameras, since the DCS Pro SLR/n is based off a consumer N80, there is a pop up flash plus a standard Nikon hotshoe which is compatible with a wide range of Nikon Speedlights that were available at the time.

The back of the camera has a variety of physical buttons for controlling the various modes of the 2.0″ LCD screen, plus delete and microphone buttons for video recording. There is an up/down/left/right directional pad with a lock around it to prevent accidental usage. To the left of the eye piece are buttons for bracketing and flash control. The viewfinder has an adjustable diopter that helps people with poor vision see through the viewfinder easier. Lastly, there is a control button and switch which allows you to set the AE or AF lock.

Beneath the up/down/left/right directional pad on the back of the camera is a hinged door for both the CompactFlash and combined SD/MMC memory card slots. I only had access to a CF card, but I believe you can use both at the same time as the menu seems to suggest the SD/MMC slot can be designated for backup storage.

The camera’s left side has a compartment for the CR2032 battery which is used to retain the camera’s memory settings. Beneath it are rubber doors covering a serial port which is strangely labeled “Test” that the manual says can be used with an optional GPS system, an analog video out port, and the IEEE 1394 serial port. Sadly the DCS Pro SLR/n does not have a USB port as those wouldn’t have been used commonly on professional cameras at the time. IEEE 1394 ports were used for faster file transfers, but is a technology not often found on modern day computers. Without a standard USB port, I was unable to connect this camera to my PC, instead having to rely on an external CompactFlash card reader.

Beneath all of this is the opening for the proprietary lithium ion battery pack. For those who wanted to use the DCS Pro SLR/n strictly as a studio camera, there was an optional adapter that took the place of the battery pack which allowed you to power the camera using an AC outlet.

The bottom of the camera has a large sticker common on modern consumer electronics with various logos and disclaimers, and centrally located beneath the lens mount is a standard 1/4″ tripod socket. Although not in the exact center of the bottom of the camera, the tripod’s socket is located in the center of the camera’s weight for excellent balance when mounted to a tripod.

Kodak had a long history of developing digital cameras around Nikon film SLRs and this proved to be a wise decision as it allowed them to focus entirely on the digital parts of the camera without having to design their own lens mount and lens system. By partnering with Nikon, their cameras had a Nikon F-mount which is still one of the most widely supported lens mounts with lenses available in nearly every focal length imaginable. Like any Nikon SLR, swapping lenses is as simple as pressing a button near the 3 o’clock position around the lens and twisting. The DCS Pro SLR/n has an in body focus motor which means it is fully compatible with all AF and AF-S lenses. Near the 4 o’clock position around the lens mount is a focus mode switch which allows you to select between Continuous, Single, and Manual focus modes.

A side benefit to using a full frame digital sensor was there was no issue with a cropped viewfinder like on the Fujifilm Finepix S1 Pro. The viewfinder is large and bright and has a green LED display with all of the standard information that would have been there in the Nikon N80 and any other 2000s Nikon film or digital SLR.

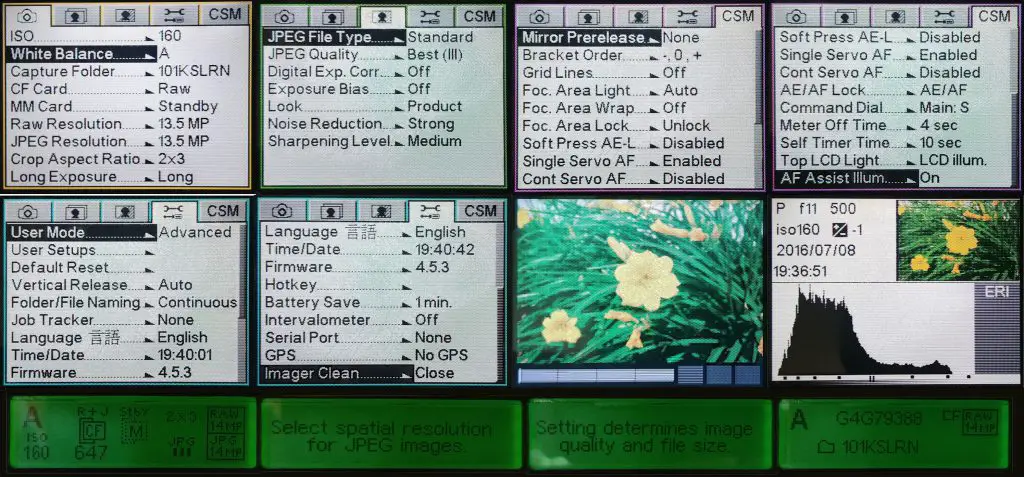

Like the Fuji however, there are still three LCD screens, one on top for basic exposure information, a 2.0″ color LCD screen for reviewing shots and viewing the menu system for controlling most of the digital camera’s settings, and a monochrome LCD display for showing information on the status of the camera.

I don’t want to go into the menus or the various modes as the camera’s several hundred page user manual covers them all. I will say that for basic functions like changing ISO and image resolution, the menu system is pretty straightforward. The software was entirely built by Kodak, so it won’t be familiar to any Nikon users, but in practice, you shouldn’t struggle too much with basic functions.

I mentioned earlier that the DCS Pro SLR/n’s only means of connecting directly to a PC is through it’s IEEE 1394 port which I did not have so file transfers were done with an external CF card reader. Although swapping cards added an extra step in transferring images, it eliminated any software issues that sometimes plague early digital cameras with modern PCs. Once I had the card connected to my Windows 10 computer, it showed up as a removable drive and I could simply copy and paste the images to my hard drive. Both the camera’s JPG and DCR (RAW) images were compatible with Lightroom CC and Photoshop CC without any additional software. In 2004, you would have had to use a Kodak program called Photo Desk to edit them, but I was able to open them in Camera Raw and edit them like I would any RAW image so software compatibility should not be a problem for anyone using this camera today.

My Results

Reviewing a digital camera is both easier and more of a challenge than a film camera in that I don’t ever need to worry about film, just needing to be sure the battery is charged and I can take it with me. The challenge though is that with the expectation of a modern DSLR to deliver digital-quality shots it can be difficult to find the right types of shots that accurately show off what the camera could do.

One challenge that I did encounter with this camera is that due to it’s age, the battery life is very short. Thankfully after purchasing the camera, I was able to locate a seller that had three of them. Each of the three would charge and could power the camera on, but as you might expect from any 15+ year old rechargeable battery, their lifespan isn’t what it was, and according to period reviews of this camera when it was new, even fresh batteries didn’t last long.

Every time I would take out the camera, I was sure to have at least two of them freshly charged and only in one instance did I ever run them low enough to where the camera wouldn’t shoot any more. Depending on my usage of the LCD, I found that I could safely get about 50 shots from a battery before the low power indicator turned on.

I decided to create two different galleries of my shots with the DCS Pro SLR/n, the first is me just using it as I would any normal DSLR. I mainly stuck to outdoor shots with the ISO set to 160. The second, which I’ll show below demonstrates the camera’s low ISO capabilities. Since shooting at any ISO lower than 160 requires extremely long shutter speeds, I had to mount the camera to a tripod, limiting my flexibility.

For the first gallery, I shot about half of the images using an AF Nikkor 24-120mm f/3.5-5.6D zoom, and the other half with an AF Nkkor 50mm f/1.8 prime. Although both lenses predate the DCS Pro SLR/n, they are both listed as compatible lenses in the ‘Lens Compatibility’ section of the camera’s user manual and likely popular choices for those who purchased this camera new in 2004.

Both lenses performed well optically, but auto focus speed on the 24-120mm zoom was much slower, which is behavior I’ve seen with that lens mounted to other AF Nikon SLRs so it has nothing to do with the DCS Pro SLR/n.

Sharpness and detail in the images is impressive, especially so considering this is a 16 year old digital camera. When images are viewed full size on a 24″ computer monitor, I cannot see any difference in detail or sharpness compared to my Fujifilm X-T20 digital mirrorless camera. It’s not until you start ‘pixel peeping’ do you really see differences, but even then, they’re negligible. Many digital cameras had something called an anti-aliasing filter which removes an optical artifact called moiré, which shows up in fine vertical lines at the expense of some sharpness. Cameras without these anti-aliasing filters are said to produce sharper images which combined with the 13.5 megapixel full frame sensor, results in some really nice looking images.

Another observation that I’ve noticed is a slight pinkish discoloration on the left side of some images. It is most obvious in the bowling alley shot but I’ve seen it on others too. Each of the images that show the discoloration were some of the more recent shots I’ve made which suggest that perhaps the sensor is failing as it did not appear in the outdoor fall foliage pictures which I took late last year when I first got the camera.

In his 2005 review of the earlier Kodak Professional DCS Pro 14n, Ken Rockwell criticizes the 14n as being built on the platform of the plastic “consumer” N80, suggesting the camera and it’s shutter wouldn’t be up to the task for professional photographers. To his credit, the N80 was a consumer camera and didn’t have the types of upgrades that the F5 or F6 would have at the time, but now in 2020 we have the benefit of hindsight to see that of all the criticisms of the DCS Pro 14n and DCS Pro SLR/n, reliability was not one of them. Many professional photographers used these cameras successfully without worrying about how well they were built.

Some of the more accurate criticisms are in how long it takes for the camera to power on. Once again, he refers to the earlier 14n, but I’ve noticed the same behavior on the SLR/n as the camera will not respond for the first 10 to 15 seconds after turning it on. The monochrome LCD screen on the back of the camera shows a boot logo and eventually “Recalibrating” and the red card access LED blinks suggesting there is some sort of firmware boot happening. A similar delay occurs when turning the camera off where the monochrome LCD stays illuminated for a good 10 seconds suggesting that the Nikon power switch does not directly control power to the Kodak parts, merely acting as some sort of shutdown trigger.

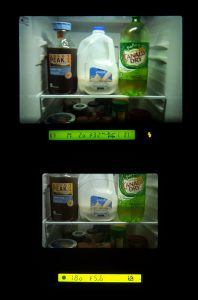

Another major criticism of the DCS Pro 14n and DCS Pro SLR/n by other reviewers is in high ISO image noise. This was the main issue that Kodak addressed with the later SLR/n so there is some improvement here, and compared to what we expect from cameras today, even with these improvements, the DCS Pro SLR/n would be dreadful, but for my eyes, it’s really not that bad. Looking at the images above, digital noise is hardly present, even in the indoor scenes. It is only when you crank up the ISO to 320 and beyond does it start to show, and once again, compared to a modern digital camera today, it’s worse, but for a 2004 camera, I’d consider this to be very acceptable.

I shot the two sequences above with the AF Nkkor 50mm f/1.8 and the camera on a tripod in Programmed AE mode. The shots of the flowers were taken during sunset when there was still a decent amount of ambient light and the shots of the school were taken over and hour after sunset with the sky nearly black. With the camera stabilized on a tripod, it could use as slow of a shutter speed as it needed since the point of this test is to show the effects of noise at the indicated ISO.

For this experiment, I used RAW images imported into Adobe Camera Raw with the only tweak being the color temp set to Auto. I added the yellow ISO label and then saved the images to JPG with no other processing. I performed a shot at every single ISO the camera was capable of, including some in between settings like 500, 640, and 1000, but I am limiting the gallery to 160, 320, 800, and 1600 as there wasn’t significant differences between every setting.

In the flower shots, the noise is visible as the ISO is increased, but I don’t consider it that terrible, especially at 1600. The noise is much more visible in the school pics where a slower shutter speed was used. In hindsight, I should not have used full Programmed AE mode as the low light images, the camera chose an aperture of f/2 which increased softness and some haloing around the light sources. Since I was using a tripod, I should have set it to Aperture Priority with a fixed f/5.6 or f/8 aperture.

It’s interesting that despite making every attempt at keeping the shots consistent, with the only change being the ISO, the exposure is slightly darker in the ISO 160 shots than the others, and the color balance is a little more bluish in the ISO 1600 shots, suggesting there was more going on in the camera’s electronic brain at these settings.

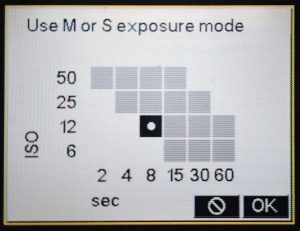

This next gallery is using the same setup, but this time using the four Low ISO settings, ISO 50 @ 2 seconds, ISO 25 @ 4 seconds, ISO 12 @ 8 seconds, and ISO 6 @ 15 seconds. In order to enable these slower speeds, you must navigate through the camera’s menu and select them on a grid, only allowing four different selections of shutter speeds at each ISO. In the image to the right, you can see all possible combinations of shutter speed and ISO. It is not possible to select an ISO 6 using a fast shutter speed. You must also have the camera set in either Shutter Priority or full Manual exposure modes.

Any concerns about noisy images are completely gone at these slower speeds as all of them, even the ISO 50 shot look great. Sharpness is also improved as the camera chose an aperture of f/22 for each shot of the flower and between f/5.6 and f/8 for the school pictures.

Although I was generally pleased with some of the “normal” shots in the first gallery, it is these low ISO shots that are the DCS SLR/n’s strengths. This clearly is a studio camera that benefits from stabilization and slower speeds.

On a large computer monitor with the images scaled to fit the screen, the differences between the different speeds are hard to spot. At first, I couldn’t even differentiate between the ISO 6 – 50 shots. It wasn’t until I did some pixel peeping of the framework of the school building could I really tell a difference.

The four Low ISO shots look significantly better than the four fastest ones. ISO 50 has a pleasing grain, almost like a film emulation mode that you might see on a modern digital camera. ISOs 12 and 25 are extremely smooth with only a the subtlest hints of grain, and ISO 6 is so smooth, it almost looks like a 3D generated model. The surfaces are so smooth, when I saved these files as JPGs, even though I chose high quality in Photoshop, it compressed the hell out of the file because there was almost no difference between pixels of similar surfaces.

Once again, I shot the 160 – 1600 shots with the camera in full Programmed AE mode which turned out to be a mistake because it chose an f/stop of f/2 for them all, which reduced sharpness. ISO 160 is the only one where I can say the grain is pleasing. Even as early as 320 do we start to see some color artifacts in the detail areas. At 800, color splotches are all over the place, and at 1600, the image looks like some kind of child’s water color painting.

The Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n is an interesting camera that’s historically significant as being the first Nikon based full frame DSLR. I definitely appreciated using my Nikkor AF lenses on a digital camera without a crop factor. The camera’s full frame 13.5 megapixel sensor with RAW image support meant that many of the images I got from it were excellent, and easily on par with that of my Nikon D7000.

The problem was with consistency. Although I mentioned that ISO noise wasn’t as big of a deal as Ken Rockwell suggested, it is still there, and the D7000 which came out only 6 years after this camera was significantly better. I also noted that the Kodak sensor clearly has a different color balance than I am used to. Looking at images shot in ideal lighting with low noise, skin tones appeared to be a little “off” which is odd considering this camera likely would have been used in a studio for portraits. Perhaps it just requires better calibration or some tweaks buried somewhere in the camera’s manual but again, it’s something to consider.

I generally had no issues with the camera’s ergonomics as it worked similarly enough to other Nikon DSLRs I’ve used that it didn’t take much reading to maneuver through the camera’s basic controls. Having the hand strap was a huge plus to accommodate the camera’s weight that might have been more of an issue if I just used a simple neck strap.

One thing Ken Rockwell said in his review of the DCS Pro 14n is that Kodak had “too many engineers and not enough photographers”, and I think this is a fair statement because no matter how technically impressive this camera is, it is still very much a Nikon film SLR with a digital camera made by someone else grafted onto the back. The slow power on and off times are obvious signs that the two electrical systems weren’t as integrated as either company likely wanted you to think. Having three LCD screens might have been acceptable in the 1990s or very early 2000s when the first hybrid DSLRs were being produced, but by 2004, I think photographers should have expected more.

The Kodak Professional DCS Pro SLR/n shines as a studio camera. The low ISO settings are very cool and something I wish more modern digital cameras supported. I would have liked to have been able to use those speeds at faster shutter speeds, but since ISO 100 seems to be the basement for even the most advanced digital mirrorless today, I won’t fault it much.

I enjoyed my time with this camera, but sadly, it’s one that I likely won’t come back to again. A combination of all the issues I described above with the deteriorating usability of the 15+ year old batteries, plus that pink discoloration in some of my more recent images suggest that this camera is already past it’s “Use By” date and likely will be permanently designated a shelf queen very soon. If you are interested in acquiring a DCS Pro SLR/n for yourself, I advise you to do it quickly as with each passing year, finding a working one will likely get more and more difficult.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kodak_DCS_Pro_SLR/n

https://www.dpreview.com/articles/4126164623/kodakdcsproslrn

https://www.cnet.com/reviews/kodak-dcs-pro-slr-n-review/

https://www.imaging-resource.com/PRODS/SLRN/SLRNA.HTM

https://luminous-landscape.com/kodak-dcs-pron/

http://www.robgalbraith.com/content_page3f6c-2.html?cid=7-6452-6696

https://www.shutterbug.com/content/kodaks-pro-slrnbrkodak-roars-back-revised-digital-slr

Well, if I could get one for $35 and have it sit on the shelf so that one day, just one person, says, “Huh? When did Kodak make that?” — hah hah! Thanks Mike!

The pjotographers are the weakest links here – this camera still has no equals in today’s world in terms of colour and things achievable in slow ISO mode. The austhor just did not bnother to learn how to get the best of it deep enough. And there is plenty of resources on a web including custom post-Kodak firmwares and way better profiles for Adobe ACR/Lightroom than are out there. Start with DPReview forum for Kodak DSLR – you can easily see there what that camera is capable of as well as get the firmware information and other references including how to deal with uneven sensor colour (so called italian flag problem)

Hi Mike, I enjoyed reading the information in your post, it brought back a lot of memories. In particular the information about the Kodak DCS cameras. In 2005 I was tempted to purchase a new one but thought about it for a long time during which Kodak had pulled the plug on digital SLR’s by the time I decided to give it a try. I eventually tracked one of the last available SLR/c’s down at Adorama in New York and purchased it. At the time I thought the images at low ISO’s (160) very good.

I still have the camera which works perfectly after only about 2000 shutter actuations and complete with about 10 batteries which I bought after the camera had become obsolete. 8 of the batteries have never been used and kept in a fridge stored flat as I read how that is how they shout be stored. The last time I tried the camera with the two batteries kept in the camera case which had not been used for 4 years, I just plugged the battery in and the camera powered up with the uncharged battery. The key to using the camera was charge the battery and keep it out of the camera until to be used, a newly charged battery left in a switched off camera would flatten the battery within 24 hours. When in use turn camera off if not immediately required for another shot. I agree with you the extended low ISO mode produced incredible results for the time. I still have all the original packaging, box and literature for the camera perhaps the only missing thing may be the remote control. I have tried in vane to find out what the production run for the SLR/c was because I purchased one of the very few left available, Adorama only had 2, even so the serial number of mine I think is 1420 so not many were made, I still have quite a few very good images from this camera. Happy memories huh. Thanks for the post.

Wow! Very cool! I wonder if the batteries for the SLR/c work on the SLR/n. If mine ever stop holding a charge, I know who I’ll be contacting to buy one! I definitely like these cameras and you’re right, at ISO 160, the images look great. Being able to shoot down to the lower ISOs is very cool too, even if it means you have to use a tripod. I sure with Kodak had stuck with DSLRs longer as it would have been interesting to see what they could have come up with in the next decade! Thanks for coming here and sharing your story!

Hi Mike, Thank you for your reply. The batteries for the SLR/c and SLR/n are the same. If you want a couple I will send them to you free if you pay the postage and the carrier will accept them (You have my email address, email if you are interested or want Photodesk installation files). The stand out feature of the Kodak SLR’s was colour quality, quite close to Kodachrome 25 and 64 depending how much saturation and contrast was applied but only when processed on Photodesk with Kodak’s ICC profiles. Of all the cameras I have owned (you obviously have owned more) nothing else quite matches the colour quality. You say you have problems with colour cast, using non Kodak ICC profiles can screw up the colour quality, subtly or severely when using other editors, look at this link for a severe case, I have had similar using other profiles on non Kodak editors (http://www.nikonweb.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=858&sid=fc76d7c69cb07f6012e960574ae990bd). A few years ago I changed my computer and was gutted to find Photodesk did not work with Windows 8 or 8.1, until I read a post on Old Nikonians saying that one of the DLL files needed to be changed, then success. Yesterday I installed Photodesk on Windows 10 and it runs perfectly, I still have all the install files.

There is a section on Old Nikonians dedicated to the early Kodak digital but a lot is about the pre DCS SLR’s, according to some posts the early stuff is starting to fetch good money now, I’m not sure how true it is.

Re Photo Desk, there is a Windows 8 and up (tested on Windows 11 too) compatible kodakcms.dll file (v. 5.4.0.2) available on this website, which is also part of QuarkXPress software installation:

https://www.exefiles.com/en/dll/kodakcms-dll/

Simply replace the old kodakcms.dll (v.5.1.001) with this updated version in the installation directory, and Photo Desk works fine.

I still rock “that” Kodak like it’s my everyday shooter! Always have it with me and try to squeeze in a couple of shots. Has something ‘magical’ about it the way it renders light. Also is very pleasant in skin tones and can produce a crazy amount of detail and sharpness. I LOVE THIS CAMERA! If I were to give up every cam I own this one is the last one to go. I have used it in every occasion, from studio to sports and I work with the camera rather than having it working for me… if that makes any sense.

Batteries is indeed an issue and they drain very quickly, couple of years ago I was lucky enough to find a few aftermarket batteries but the miss the door and locking mechanism so I only use them indoors afraid to get moisture inside.

Anyway fun reading your thorough review.

Cheers!