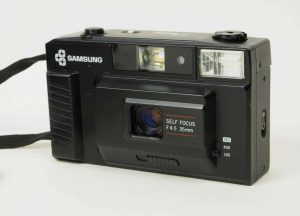

This is a Samsung SR4000, a 35mm single lens reflex camera made by Samsung in South Korea from 1997 to 2001. The SR4000 is the North American name of the Korea only Samsung Kenox GX-1. It was Samsung’s first and only 35mm SLR, which they produced during the short period of time the company owned the German optics firm, Schneider-Kreuznach. The SR4000 is unique in that it has every single automatic feature of an advanced consumer SLR of the era, except auto focus. The camera is totally manual focus, featuring both a split image and microprism collar focusing aides in the viewing screen. It uses a unique Samsung only bayonet lens mount to which only four lenses were ever made, three zooms and a 50mm f/1.4 prime which was branded as a Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 28-70mm f/3.5-4.5 Samsung coated unknown (probably 10-11) elements

Lens Mount: Samsung Bayonet

Focus: 1.5 feet to Infinity

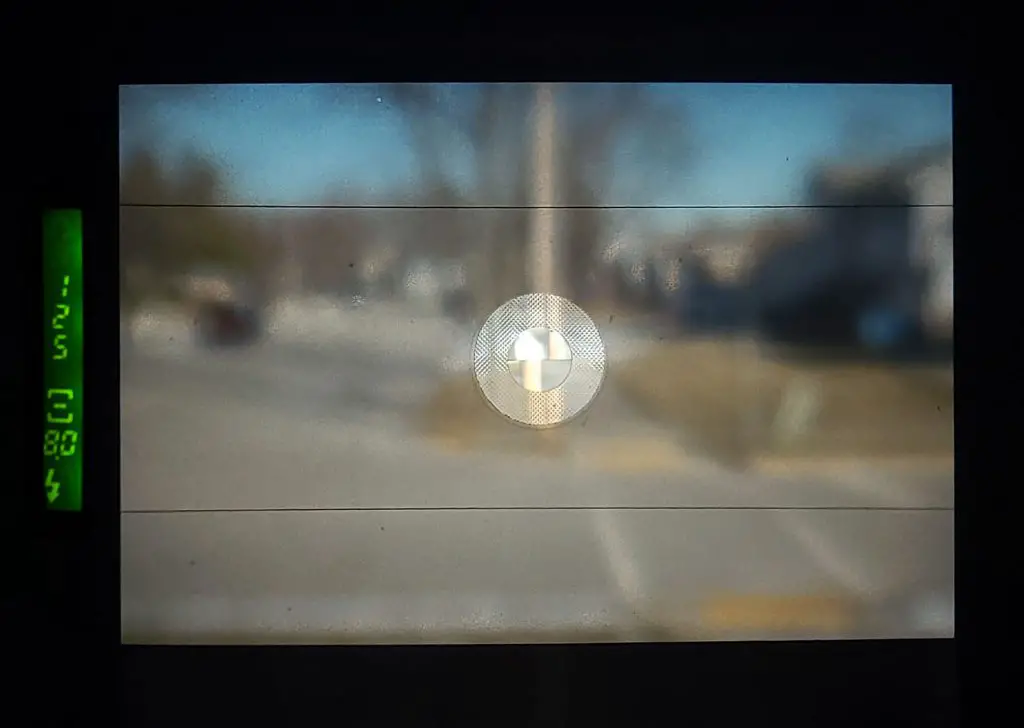

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with full information LCD Read Out

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 30 – 1/4000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Silicon Photo Diode meter with Fully Programmed AE

Battery: (2x) 3v CR2 Lithium Battery

Flash Mount: Hot Shoe, 1/125 flash sync speed

Weight: 824 grams (w/ lens), 446 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SamsungKenoxGX1Manual.pdf (in Korean)

How these ratings work |

The Samsung SR4000 was the first, and only 35mm SLR camera produced by Samsung. It was very unique not only because of who made it, but it also had all of the features of a modern SLR except auto focus. The SR4000 had a unique bayonet lens mount which only ever had three lenses made for it. The camera is typical of a consumer quality SLR from the era, but has several shortcomings which make it less than ideal to use. It sold poorly when it was first released and was discontinued quickly. Although Samsung would go onto greater success in other areas of electronics, 35mm film SLRs was not one of them. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 6.0 | ||||||

History

This article tells the tale of two Samsungs, one you probably already know and another you might not. As I write this in early 2021, the Samsung you know is one of the largest global electronics companies in the world. Samsung smartphones and televisions are leaders in their respective industries, but the company is involved in the manufacture of far more than just consumer electronics.

The other Samsung, is a company that twenty years ago was a relative newcomer to most of the non-Korean world. There was once a time when the thought of buying anything from a small South Korean company was considered a risk, and one that many people (myself included) would have never considered.

For frequent readers of this site who have learned about the early days of the Japanese camera industry, the history of Samsung is quite similar as it involves a modest company formed by an unknown businessmen who through hard work and dedication, built a global empire.

In March 1938, a South Korean businessman named Lee Byung-chul formed Samsung Sanghoe, or Samsung Trading Company in Taegu, Korea. The word “samsung” means “three stars” which loosely translates to something that is big, powerful, and everlasting.

Samsung was a trading company that dealt with groceries such as fish, noodles, and other locally grown foods, exporting them to China and it’s provinces. The company grew rapidly, and in 1947 moved it’s headquarters to Seoul, the nation’s capital. By the end of the Korean War, Samsung had expanded into textiles, eventually building the largest woolen mill in South Korea.

Lee Byung-chul had a goal of rapid industrialization and to help rebuild Korea after the war. He gained support from the South Korean government who put into place a system of protectionist policies that provided Samsung easy financing and shielded them from competition in their respective markets.

Over the next several decades, with support from the government and very little competition, Samsung prospered, expanding into a large variety of industries such as insurance, securities, retail operations, and even heavy industries such as ship building.

In 1969, Samsung entered the electronics industry with several new companies that would focus on different areas, such as telecommunications, semi conductors, and consumer electronics. The consumer electronics division was called Samsung-Sanyo Electronics and in 1970 released it’s first product, a simple black and white television called the Sanyo P-3202.

Samsung TVs were predominantly made for the Korean domestic market with some exports made for markets such as Panama, but they were still unknown to western countries like the United States.

Over the next decade, Samsung Electronics would release a huge variety of products such as VCRs, air conditioners, calculators, and household appliances such as refrigerators, microwave ovens, and washing machines. The company would open it’s first office in the United States in 1978 although it is not clear if any of their products were sold here.

The 1980s saw continued expansion of Samsung’s products into semiconductor and computer industries. Lee Byung-chul would pass away in 1987 and his role as company chairman would pass onto his son, Lee Kun-hee who took on the task of restructuring and consolidating the company’s many divisions. Lee Kun-hee had ambitious goals for his father’s company and set a goal to make Samsung one of the world’s top 5 electronics companies, aiming to compete with Japanese powerhouses such as Sony and Panasonic.

At the same time Samsung was setting a goal of consumer electronics dominance, another of Samsung’s subsidiaries called Samsung Precision in 1979 produced the company’s first closed circuit television camera. Samsung Precision was largely invested in aerospace technologies, and in 1987 changed it’s name to Samsung Aerospace Industries. It is not clear what role photographic cameras played in the company’s portfolio at the time as it seems they were mostly involved in commercial aviation constructing jet engines and helicopters.

In 1995, Samsung Aerospace Industries would acquire the German optics firm, Rollei Fototechnic GmbH & Co. from a Polish entrepreneur named Heinrich Manderman who throughout the later part of the 20th century, bought many different German optics firms such as Rollei, Schneider-Kreuznach, B+W, ORWO, and Pentacon.

In 1995, Samsung Aerospace Industries would acquire the German optics firm, Rollei Fototechnic GmbH & Co. from a Polish entrepreneur named Heinrich Manderman who throughout the later part of the 20th century, bought many different German optics firms such as Rollei, Schneider-Kreuznach, B+W, ORWO, and Pentacon.

It is not exactly clear what Samsung’s interest was in Rollei, who was once one of Germany’s premiere camera making companies but it was likely to secure a licensing deal with another of Manderman’s companies, Schneider.

Prior to Samsung’s acquisition of Rollei, their earliest consumer cameras were inexpensive models like the Samsung Winky from 1986 which was a rudimentary focus free 35mm point and shoot model. Now with a licensing agreement with Schneider, Samsung could improve their reputation in the camera industry with Schneider’s lens technology and reputation.

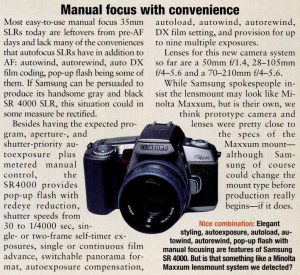

In early 1996, Samsung announced that they were preparing to enter the single lens reflex market, with an upcoming new model called the SR4000. The SR4000 would differentiate itself from other currently available SLRs by lacking auto focus, while featuring state of the art technologies not often found in legacy manual focus SLRs of the time. The short blurb to the left from the May 1996 issue of Popular Photography reveals a two-tone black and gray model with an unbranded 50mm f/1.4 lens, and a list of features that include a top 1/4000 shutter speed, four P, S, A, and M metering modes, a pop-up flash with redeye reduction, a panorama mode, and that at least three lenses would be available upon launch..

Neither a price, nor any reference to Schneider branded lenses was mentioned in the preview, but the article suggests that the Samsung’s lens mount strongly resembled Minolta’s Maxxum mount, a rumor that would persist for years after the camera’s release, later clarifying that the mount was unique to Samsung

When it was released in 1997, the camera was sold in South Korea as the Samsung Kenox GX-1, but elsewhere as the Samsung SR4000. The price in September 1999 for the SR4000 with the Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon 50mm f/1.4 lens was $499.99 which when adjusted for inflation compares to almost $800 today, quite a high price for a manual focus SLR from a company not known in the SLR market. It’s likely the camera was immediately sold with deep discounts, as I found magazine ads from places like New York’s Cambridge Camera Exchange who had it advertised for $389.

Upon it’s release, only three lenses were available, the Schneider branded 50mm f/1.4, and two zooms, a 28-70mm f/3.5-4.5 and 70-210mm f/4-5.6. Both zoom lenses were branded as Samsung lenses, but this site suggests that all three were developed by or with cooperation from Schneider. Page 56 of the Korean language user manual for the Kenox GX-1 suggests a fourth lens, a 28-105 f/3.5-4.5 zoom, but I couldn’t find any evidence that it was actually made.

Samsung gave the camera it’s own unique lens mount, but a persistent rumor which started with the May 1996 prototype article shown above suggests that the Samsung SR4000 used the same, or a modified version of the Minolta Maxxum mount. Although the two mounts do share some similarities including size, location of the lens mount release pin, the screw holes, red dot, some of the electrical contacts, and very similar locations for the three bayonets, the lens mounts are definitely different. You cannot mount a Maxxum lens to the SR4000 or vice versa.

The animation to the left shows a loop of the Samsung’s mount with that of a Minolta Maxxum superimposed over it. As you can see, similar yes, the same, no.

Neither the domestic Kenox GX-1 or export SR4000 sold well in Korea or anywhere else. It took me years to find this example, and as I write this article, there are none for sale on the US or International versions of eBay.

While researching this article, I made contact with a Korean photographer named Yong-Hoon Kim who has owned a Kenox GX-1 since 2001 and in February 2005 was interviewed in this Korean language newspaper article. I spoke to him separately and he confirmed to me that the camera sold poorly due to being only partially developed. By the time of it’s release, Korean photographers demanded auto focus, and the lack of enough modern conveniences made it unappealing. He goes on to say that by the time he bought his in 2001, production of the camera had already stopped and that remaining inventory could still be bought at a huge discount.

In my research for this article, I found no advertisements or hands-on reviews about this model in any of my usual sources. The only time I could find references to the camera in US publications were in back of magazine ads around 2001 for shops like B&H Photo selling the camera with lens for as little as $169. In my conversation with Yong-Hoon above, I asked if it was advertised in South Korea and he said Samsung did not promote this camera, theorizing that perhaps they knew early on they would not be able to continue to develop the camera system.

Whether it was a direct result of the failure of the Kenox GX-1 or a symptom of bigger problems within the company, Samsung would sell back it’s ownership of Rollei to Heinrich Manderman in 1999, ending it’s use of the Schneider brand name. Development of any other lenses or other 35mm SLRs was halted as the only photographic cameras bearing the Samsung name would be simpler point and shoot models.

Shortly after the start of the new century, Samsung would begin focusing on digital cameras and smartphone products, both market segments the company would soon dominate. By the summer of 2013, Samsung’s line of Galaxy smartphones would become the best selling line in the world, beating out all competition, a lead they still maintain to this day.

Today, Samsung’s early days as a maker of 35mm film cameras is largely forgotten with only a spattering of compact point and shoot models popping up in collections from time to time. The existence of a 35mm SLR is likely news to someone reading this article, so you’d be forgiven if you had never heard of it, but with a mostly forgettable design, poor selection of lenses, and a feature set that appealed to very few people, it is a model that has stayed forgotten through the years.

My Thoughts

When it comes to selecting cameras to review, I tend to shy away from 1990s and 2000s fully automatic autofocus cameras because I find that it’s difficult to come up with enough to say about them. These cameras are still new enough that most people remember them today, and in the case of film SLRs like the Nikon F5 and F6 or comparable models by Canon and Pentax, they’re the basis of what modern day DSLRs are still like.

On occasion though, I’ll consider a model from this era if there’s something different or special about them, and in the case of the Samsung SR4000, this was a camera that was both different and special. It is different as it was one of the only fully automatic and modern film SLRS to be manual focus only, and it is special because it was the first, and only Samsung film SLR, and a camera that hinted at that company’s later dominance in the consumer electronics market.

I can’t remember the first time I learned of the Samsung SR4000, but when I did, I began a search to find one, only to discover that it would be a very elusive camera to find. Typically, when there is a camera I am interested in, I will set up search alerts in eBay so that any time something is posted that matches my search, I’d get an alert. For over two years, I found only one SR4000 posted online and it didn’t come with a lens and also looked to be broken. There was a Korean Kenox GX-1 once too, but the price for it and shipping made it prohibitively expensive.

I figured that maybe one day one would come along at the right price, and as I talked about in my GAS Attack! Buying Cameras on Ebay article, one of the key requirements to building a collection of cameras cheaply is to have patience. My patience eventually paid off, as this very nice and fully functioning Samsung SR4000 (with lens) was soon in my hands.

The build quality of the SR4000 is on par with that of other consumer grade SLRs of the late 1990s and early 2000s, but it wont impress you in the same way a Nikon F2 might. When you first pick up the SR4000, it’s 824 gram weight suggests a sturdy camera, but when you realize that 378 of those grams are from the 28-70mm f/3.5-4.5 Samsung zoom lens, you realize that the camera itself is quite cheap feeling. Even though this was Samsung’s first film SLR, they were no stranger to cameras or electronics in general as they had over a decade of experience making cameras and several decades worth of making pretty much everything else, so the lightweight cheapness of the SR4000 is a bit disappointing.

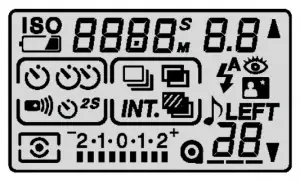

The top plate looks much like most SLRs of the day, dominated by a large multi-function LCD screen on the right which shows most of the camera’s settings. A round mode knob on the left has all the familiar settings for P, S, A, and M exposure modes, a few icon-based shooting modes intended to simplify complicated features for novices, plus settings to manually set ISO and turn off the camera’s beeps. A button in the center of the dial with the letter M on it is a lock that prevents the dial from accidentally being changed.

Above and to the right of this dial is a self-timer and remote release button. Above the pentaprism is the pop-up flash and flash hot-shoe connector. This camera still came with the little plastic thingy in the flash shoe that protects it when it was new, suggesting it was not frequently, or perhaps not ever used.

The large rectangular LCD screen shows many of the same features as other SLRs of the day, including exposure information, shooting mode, exposures made, EV compensation, focus mode, flash mode, and several others.

In front of the LCD is the shutter release button surrounded by a selection wheel which is used to cycle through things like shutter speeds, ISO speeds, and exposure compensation. A separate, smaller wheel right behind the LCD screen is used to change aperture. Both of these dials were a bit rough to turn on this example, but that could be the result of over 2 decades of age, or perhaps the plastic used on them just didn’t hold up well.

To the right of the LCD is a drive mode button and the camera’s main power switch. The power switch is strangely recessed into the body, and due to it’s narrow width, was difficult to use, often requiring me to shove a fingernail to catch one of the bumps to turn the camera on and off.

The camera’s bottom is where you’ll find a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, door for the 2x CR2 battery compartment, a small recessed button for manually rewinding the film, and a slider switch to activate the camera’s cropped panoramic mode. Panorama modes were popular briefly in the late 1990s and early 2000s by adding a mask both in the film compartment and viewfinder cropping the full frame 24×36 exposure to a panoramic 18×36 image.

The camera’s left side is where you’ll find the film door release latch, an exposure compensation button, flash mode button, and a side view of the front lens release button. This side also gives a good look at the depth of the 28-70 Samsung zoom lens.

The film compartment is modern, with standard left to right film transport onto a thick rubber take up spool. Loading film into the SR4000 is very simple as all you do is extend the leader to the very edge of the spool, close the door, and let the camera do the rest. The SR4000 has a sprocketless design, instead using a small rectangular optical sensor for sensing film transport.

Other things here are the contacts for DX film detection, an oversized and dimpled film pressure plate with two openings for the date back, a battery compartment inside the door for the date back, a small release near the door hinge for removing the door, and the opening for the small window allowing you to see the film cassette with the door shut.

The back door of the camera has the LCD screen and control buttons for the date back. Unlike some other cameras in which the date back is an option, this was a standard feature on the SR4000. The door is removable though, and looking at the pictures in the Korean language manual for the Kenox GX-1, I do not see any options for any other kind of back, so perhaps one was planned but never developed.

The viewfinder is a mixture of good and bad. Starting with the good, the focusing screen is consistently bright across the entire image, even in the corners which makes composing in less than ideal light easy. This is impressive considering this example has the Samsung 28-70 zoom lens with a maximum aperture of only f/3.5. I imagine that if I had the 50mm f/1.4 Schneider Xenon, it would have been much better. It was also welcoming to see a familiar split image focus aide surrounded by a microprism collar which are missing on nearly every consumer grade SLR made after the start of the autofocus age. There is also a backlit green LCD display on the left that shows most of the useful shooting information for most situations. Finally, two permanent horizontal lines help frame your image when shooting the camera in panorama mode.

Now for the bad. I did not care for the location of the green LCD on the left side. Although the sides were commonly used in the 1960s and 70s for match needle or analog shutter speed displays found on early metered cameras, there is a reason that nearly every film and digital SLR made in the last 30 years has it on the bottom. As a wearer of prescription glasses, I found it difficult to see the screen without having to shift the position of my eye to the side. This might be less of an issue for people without glasses, but for me it was a constant source of annoyment.

A side effect of the split image focus aide while using a slower f/3.5 lens means that you must take care to look at it perfectly straight on. If your eye moves the tiniest amount, half of the split image will darken. This is normal behavior on any camera that has this feature when using a slower lens, but I imagine that the zoom lenses are the ones most commonly found on this camera and it somewhat tarnishes the appeal of manual focus. I found that while shooting, especially in low light, the split image would regularly disappear, causing me to miss focus on a few shots.

These usability issues aside, the Samsung SR4000 has an interesting combination of features, good ergonomics, and a set of lenses that at least on paper, should be capable of great images. I’ve reviewed many one-off first cameras by companies who either never made another, or eventually would go onto greatness, so a few misses are certainly understandable, but it’s rare to see a product like this from such a big company who would abandon it so quickly after it was released. How bad could it be?

My Results

For this review, I shot two rolls of film in the Samsung SR4000, a bulk roll of Kodak TMax 100 and later a fresh roll of Fuji 200. In both instances, I tried to use the camera in ways in which the original owners might have, with a trip to the zoo and walking around my neighborhood. The SR4000 being a manual focus camera would put my manual focus abilities to the test as I wouldn’t have the luxury of sitting there with a fixed object, trying to achieve razor sharp focus.

The images in the gallery above are some of the better ones I got from those first two rolls. It would seem that my decision to test out a manual focus SLR while shooting moving children was not the smartest decision as about a quarter of the images were out of focus. Although featuring a modern viewfinder, the zoom lens’s maximum f/3.5-4.5 variable aperture was quite limiting as it darkened the viewfinder and also made using the split image focusing aide difficult, especially when zoomed in when the lens only opens to f/4.5. I believe that with the Schneider-Kreuznach Xenon 50mm f/1.4 lens, the camera would have been much easier to use, due to the increased amount of light that would have entered the viewfinder.

Of the three lenses available for the SR4000, neither of the two zooms were branded with the Schneider name despite possibly being built by them, which likely was a smart decision as I found the images to be soft and lacking in character, much like a typical consumer kit lens would. These were some of the most indistinct and overall “blah” images I’ve gotten with an SLR in quite some time.

Lens sharpness was just OK with out of focus details fuzzy and not defined. Vignetting was visible in some of the shots, most noticeably using the color film, which I cannot explain, but at the least no other serious optical anomalies were present. Overall, the images aren’t bad and likely would have satisfied any amateur photographer wanting a family camera to make 4×6 or 5×7 prints from. I did not bother trying the camera’s panorama mode as all it would do is mask the top and bottom 3mm of these exposures, so if you could just imagine black bars covering each of the images above, you can get an idea of what it would have looked like.

One nice thing I can say about focusing the SR4000 with this 28-70mm lens is that it is clear the lens was specifically designed for manual focus, as opposed to other autofocus zoom lenses that offer manual focus as an afterthought. The focusing ring is at the very front of the barrel with a thick rubber grip and has an overall width as wide as the zoom ring. Focusing motion is smooth and nicely dampened, making pleasant movements from the unmarked macro setting (probably 18 inches) to infinity.

The SR4000’s ergonomics are decent with most of the camera’s controls in the locations where you’d expect to find them on any other late 1990s SLR. The right handed grip is sufficiently deep so that holding the camera for long periods of time should not strain the muscles in your hand. The shutter release and mode selection wheel are comfortably located for your right index finger, but I found the movement of the wheel to be unrefined and cheap feeling. It is plausible that over the 20+ years this camera has existed, the wheel has worn down, but the overall good condition of this particular camera suggests it’s only seen light use in it’s life, so I doubt it.

In addition to the darkness in the viewfinder caused by the slow kit lens, I did not care for the location of the viewfinder LCD on the left side of the frame. While wearing prescription glasses, I found it harder to read the camera’s settings, compared to the more standard location near the bottom. This is probably just a personal choice for me, but there has to be a reason that by the time the SR4000 was released, nearly every other maker of SLR cameras had chosen the bottom of the viewfinder for their LCD.

Overall, the SR4000 walks that line of a forgettable consumer level SLR while not being terrible. Although I have quite a few criticisms of it, it never crosses that line into being unusable. Lens performance is on par with other kit zooms of the era, ergonomics are good, the viewfinder is OK in good lighting, and the camera has pretty much every feature (except auto focus) that someone could want, yet, I can’t shake the feeling that Samsung really missed the mark with this camera.

The market for a manual focus SLR in the late 1990s was likely very small. By then, you could probably group most people looking to buy a 35mm SLR into one of two categories, professional and amateur photographers. Professional photographers are not known to take risks on cameras made by a company without a lot of experience and a limited selection of lenses, and they certainly would have wanted a camera with a much better build quality than the SR4000’s mostly plastic and light weight body. Amateur photographers on the other hand would have definitely preferred auto focus and likely wouldn’t have invested hundreds of dollars into a new SLR system that was manual focus only.

I think that from a company with an already established SLR system with multiple models, a modern manual focus SLR might have had a chance. Had Nikon or Canon released a similar model in 1997, it would have still had a narrow market share, but might have appealed to someone who was interested in macro photography where manual focus is essential or as a backup to people who have already invested heavily into each company’s respective system.

But that’s not what happened. Samsung, a company not known at the time for quality 35mm cameras, took a swing on creating an all new 35mm SLR system, and missed. The camera was produced for a very short time, and even in South Korea where it was built, it sold poorly, eventually being discontinued and sold at close out prices on the back pages of camera magazines all over the world.

As a collector, I often enjoy shooting odd-ball “one-off” cameras with strange combinations of features. When I first read about the existence of the Samsung SR4000, I really wanted to love a modern manual focus SLR with the same kind of split image focusing aide of older cameras, but after spending some time with it, it’s cheapness, dark viewfinder, slow operation, and lackluster image quality give me clarity as to why it was so hard for me to find in the first place. The Samsung SR4000 is an obscure camera that was quickly forgotten shortly after it’s release, and it deserves to stay forgotten.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Samsung_SR4000

https://skpfoto.wordpress.com/2013/03/14/film-photography-part-1-samsung-sr-4000/

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/samsung-sr-4000-w-schnieder-lenses.48836/

https://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard_eng.php?id_appareil=6710#

https://tokinon5014.blogspot.com/2020/12/schneider-kreuznach-xenon-50mm1141649.html

http://blog.daum.net/pentax/15213293

https://www.yongbaksa.com/34 (in Korean)

https://m.post.naver.com/viewer/postView.nhn?volumeNo=23592529 (in Korean)

I very much appreciate this article:)

I’ve owned a Samsung SR4000 since 1999 and shot a few dozen rolls with it back then. Your article inspired me to dust it off and fire it up again. It still seems to work just fine!

My parents bought this for me as a graduation present and I’m pretty sure they’d have bought it at a massive discount like you mention in your article, as money “didn’t grow on trees” for our family in those days.

The camera came with both a zoom lens (70-200mm, if I’m not mistaken) and the Schneider Kreuznach branded 50mm 1.4. The zoom lens felt cheap, cheaper than the camera and quite literally fell a apart at some point. The 50mm still feels pretty solid. I’ll shoot a test roll with it this winter and report back to you regarding the image quality.

I am glad I inspired you to give the ole gal another go! Be careful of that LCD as when I got mine, it wasn’t bleeding, but after using it a couple times it is starting to bleed. It doesn’t affect the performance of the camera, just annoying. And I am definitely interested to hear more about the Schneider lens. I really wanted to try one for this review but could not find any for sale. If you ever want to sell or trade it, please let me know!

Perhaps Samsung tried to appeal to those purists who liked to know what the camera was focused on and what the depth of field looked like? Does it have a D of F preview?

I just checked and no, there is no depth of field preview button or lever. It is possible the camera was targeted at the purists, but my theory is that Samsung had never made an SLR camera before and wanted to test the waters with a simple and inexpensive model before jumping in too deep. Remember that by then, digital cameras were already started to gain some popularity, so it is plausible they never intended on going too deep with film and wanted this as a test for future digital cameras too.

Even Canon tried releasing the manual-only EOS-M about the same time and it fell on its face, too. I bought one cheaply purely to salvage the split-image screen from it, to fit into my 5DmkII, but am reluctant to disable a perfectly fine working camera until I’ve had some use out of it.

Many people have taken apart the EOS-Ms to get at the focus screen. On one hand, its a camera that’s so basic, I don’t know how many people would really want to shoot one, but on the other, I agree, it sucks to tear apart a perfectly working camera! I am glad that is a decision I don’t have to make! 🙂

Samsung had licensed to make minolta slrs, and they have ‘korean assembled’ x-300, x 700 erc. In 70 to 80s, japanese conpanies were impossible to directly sell their productsby the high tariff , and have to patner with korean companies. For example, daewoo with yashica, anam with nikon , goldstar(now lg) woth canon, dongwon with pentax, and hyundai with oylmpus. First company to make their own flim camera was dai-han optics, but defeated by janpanese-korean licensed cameras. Samsung was longest in the game, and started to develop their own cameras in 1980s. Their first own samsung-branded camera was sf-a, which minolta designed specifically for samsung. Winky is their second, and first own developed one. Their first high range camera was af-slim in 1989, and sold ‘prego af’ by rollei. Samsung had produced various cameras for other companies, slim zoom 1150 for huji super 115, fino 115 for minolta riva zoom 105 etc. ecx-1(fx-1) was samsung’s experiment in high point& shoot camera, and was quite a success at least in korean market. Samsung also had ‘ samsung watch company’ competed with “korean orient” and dolphin (handok) . They licensed seiko, seiko dolce, and longines in korean market. Samsung’s plan was to acquire rollei and luxurize whole samsung range of watches and cameras. Samsung’s own high end camera project to compete with highend market like contax t3, nikon 28ti was stamped and sold in the name of rollei qz35, one of the luxurious product samsung even made. Samsung had plans to release own rollei branded high end watches, but had brand infingment with rolex and sold only for korean market. Korea got in serious ecomomic trouble in 1997 request bailout from IMF. Daewoo-ssangyong bankrupt, kia was acquired by hyundai and lg was forced to close their semiconductor business. Samsung, had newly started own car business, acquired several companies including AST, was in serious trouble. Samsung span off watch division , sold rollei, sold union optics, sold car division, and many others. This may lead to sr4000’s half baked performance. Also from 90s, japanese companies refused korean companies to license their autofocus system. This led korean company’s licensed japanese slr to the end. Samsung had plan to put autofocus feture in sr4000, but was dropped within development process. Also minolta was in troubled with honneywell with autofoucus oatebt, so minolta was hard to help samsung if they wanted to. Sr4000 even had space to put af built in, and it is sad to use mf body in 1997. Developer said they tried their best to make camera light as possible, they even inject molded the and hard-chromium plate the prism, making sr4000 a lightweight but also caused somewhat dark finder. As sr 4000 and qz35 was initailly developed as samsung’s challenge in entering premium market, sr 4000 did their best to make company’s first flim slr, but because of harsh korean economy and their own problems (deceloper insisted about somewhat not premium paint and rubber coating) , sr 4000 was failed. However gx-1 sold a quite in korean market, and had dump in early 2000s, seconhand prices in korea is somewhat cheap. Just a great history piece of korean industry..

Wow, this is some great information! Thank you for sharing it!