There’s a saying from an old Chevrolet commercial that describes things “as American as baseball, hot dogs, and apple pie”.

Now, I like baseball, hot dogs, and apple pie, so maybe there’s something to that, but if you were to ask me, what is more American than those things, at least in the context of the mid 20th century United States. I would say…rockets. Big, tall, expensive, and extremely powerful rockets. Rockets like the Saturn V, the Atlas-Centaur, and the Titan IIIC were all big, and mighty things that used a lot of fuel, made lots of noise, and shot things way, way up into the sky!

In the 1950s and 60s, during the peak of the Space Race between the US and Soviet Union, various American companies were working out ways to make bigger, stronger, and safer rockets that could help us reach father beyond this world.

And while many of these rockets and the missions they would fly were top secret, the public was still enamored by these large phallic monstrosities, and in order to feed the appetite of the average American, someone had to take photographs of them to plaster all over the Sunday paper and in issues of LIFE magazine.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault is from the June 1961 issue of Modern Photography and details the dedicated lengths photographers had to go through to capture images of rockets during the formative years of the US and Soviet Space Race.

A full eight years before Apollo 11 landed the first men on the moon, the United States was falling behind the Soviet Union, and these images not only were useful to the US Air Force and NASA in analyzing the rockets during their ascents, but also proved to be valuable promotional tools in generating excitement for the space program.

The article starts out explaining that photography at Cape Canaveral, Florida, where a large number of rockets were launched, was big business. Consuming over half a million dollars worth of film annually ($4.56 million today) to cover hundreds of rocket tests. These photographs were extremely important, not just for publication in the New York Times, but also for scientific research purposes. Photographs during a launch test were invaluable to the engineers and scientists responsible for each launch if anything were to go wrong, so having a detailed record of each launch was critical.

As many as 372 cameras of all film formats, from 35mm still to motion picture cameras using over 2500 lenses was valued at over $4.5 million just for the equipment (over $41 million today).

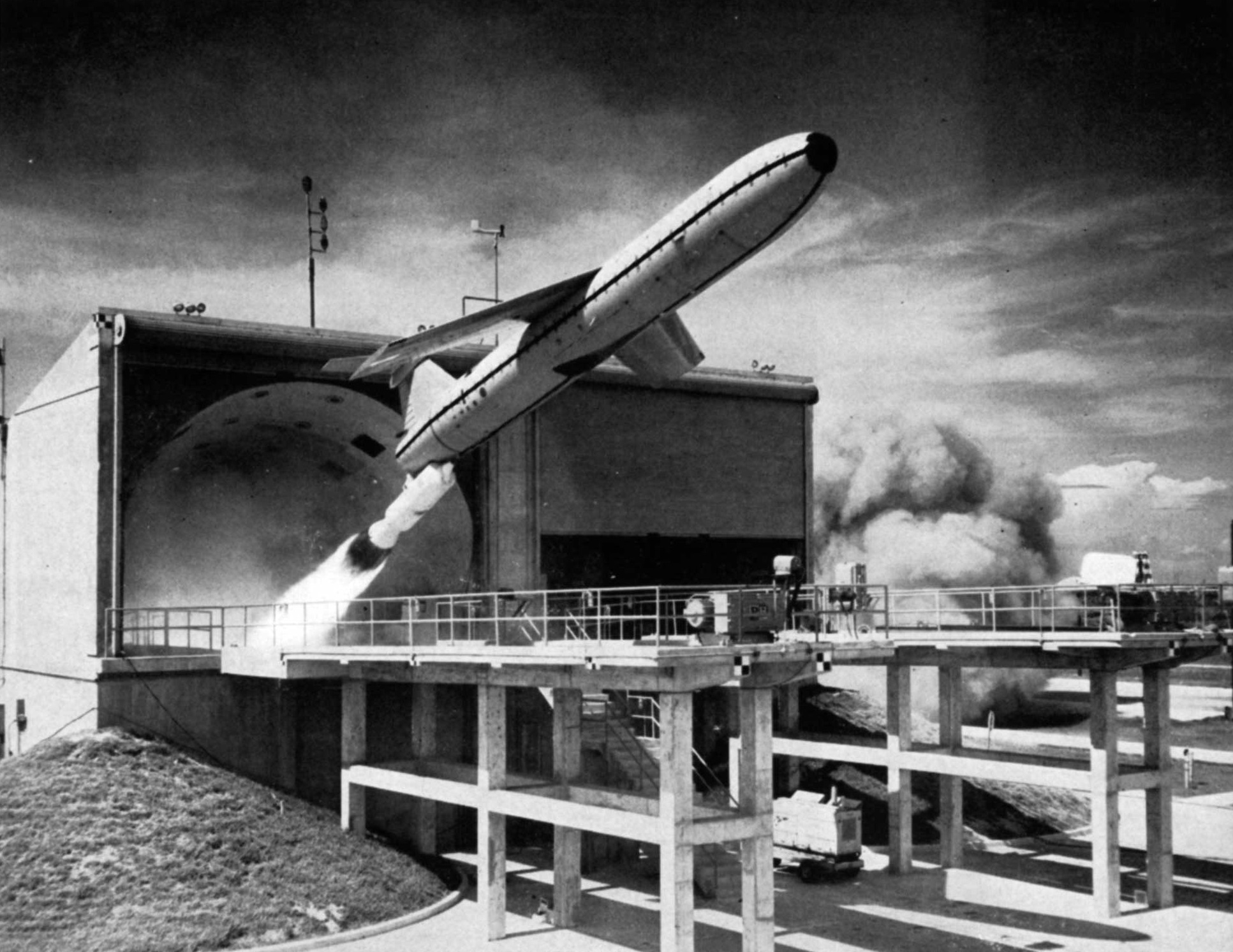

The article goes on to explain the importance of each photographers job, detailing what a typical day might be like for them. Images of construction of Saturn rocket towers, and test stages for ICBMs were just “a trip to the office” for many of these men and women. When shooting an actual rocket, the windows of opportunity to get the right shot were incredibly narrow. Not only that, but since rocket launches are inherently dangerous, a 1000 foot safety circle must be obeyed. In the case of horizontally launched rockets like the MGM-13 Mace, the photographer can’t even see the rocket until it is already in motion, so framing, focusing, and setting exposure must all be done in advance. Blink and you’ll miss it.

In the event something goes wrong, photographers have a split second to capture the unexpected, such as the image to the left from the July 16, 1959 explosion of a Juno II rocket which veered off course 100 yards away from spectators before blowing up completely.

According to the article, rocket photographers were paid well, but they hardly were household names. You don’t hear names like Ansel Adams, David Douglas Duncan, or Steve McCurry when talking about famous rocket photographers as the majority of work these people did, likely was never seen by the general public.

Their contributions to pop culture might have been small, but what they did was very important, and likely one of many key elements to the future success of the US Space Program.

I have nothing against an afternoon double-header at Yankee Stadium with a warm Nathan’s hot dog with grilled onions and yellow mustard, but I think there’s just nothing quite as American as rockets and photography!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.