I don’t know what it is about horror movies and sequels, but people don’t ever seem to get enough of them. Classic horror franchises like ‘A Nightmare on Elm Street’ and ‘Friday the 13th’ have a ridiculous amount of sequels, but perhaps even more ridiculous is how often these franchises claim to be over, with “The Final Chapter” or some subtitle suggesting that there won’t be any more movies.

But like Kiss farewell tours, they keep coming back for more. In fact, in the Friday the 13th franchise, there were two separate movies which both claimed to be the last (the second one being Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday), only to have the franchise keep chugging along.

In regards to cameras of the dead, since the first time I had the idea to do one of these articles with three dead cameras and very loosely tie them to some kind of horror theme, usually around Halloween or “Halfway to Halloween”, I think the joke has run it’s course. If I’m being honest, I probably should have stopped with last Halloween’s Cameras of the Dead 9: The Worst Ever, as I think I did a pretty good job of putting together not only three dead cameras, but three truly terrible ones, deserving of a farewell.

But who can resist the 10th in a series? I mean, it’s almost like a requirement that if you do 9 of something, you have to do 10, and if you’re doing to do 10, then you gotta use the Roman numeral X for it, because, it’s like a rule or something.

So for this Halloween, I bring to you three cameras that were dead as a door nail the moment they hit my door step. None of these ever had any hope of working, and I am OK with that. I don’t have any sample images from each, but considering the reputation of each of the three companies that made them, I am certain the images probably would have looked pretty good. I likely would have had something positive to say about each, with a couple nitpicks here and there. If you’re a long time reader of this site, you know how it goes.

Does this mean I won’t ever review dead cameras any more? Of course not, because I still have a ton of them, but for future cameras of the dead, I’ll likely just stick with one offs, here and there.

But like we’ve seen with any good franchise, the second anyone claims something to be the last, pretty much guarantees it won’t, so I guess only time will tell whenever an 11th edition is posted!

Minolta V2 (1958)

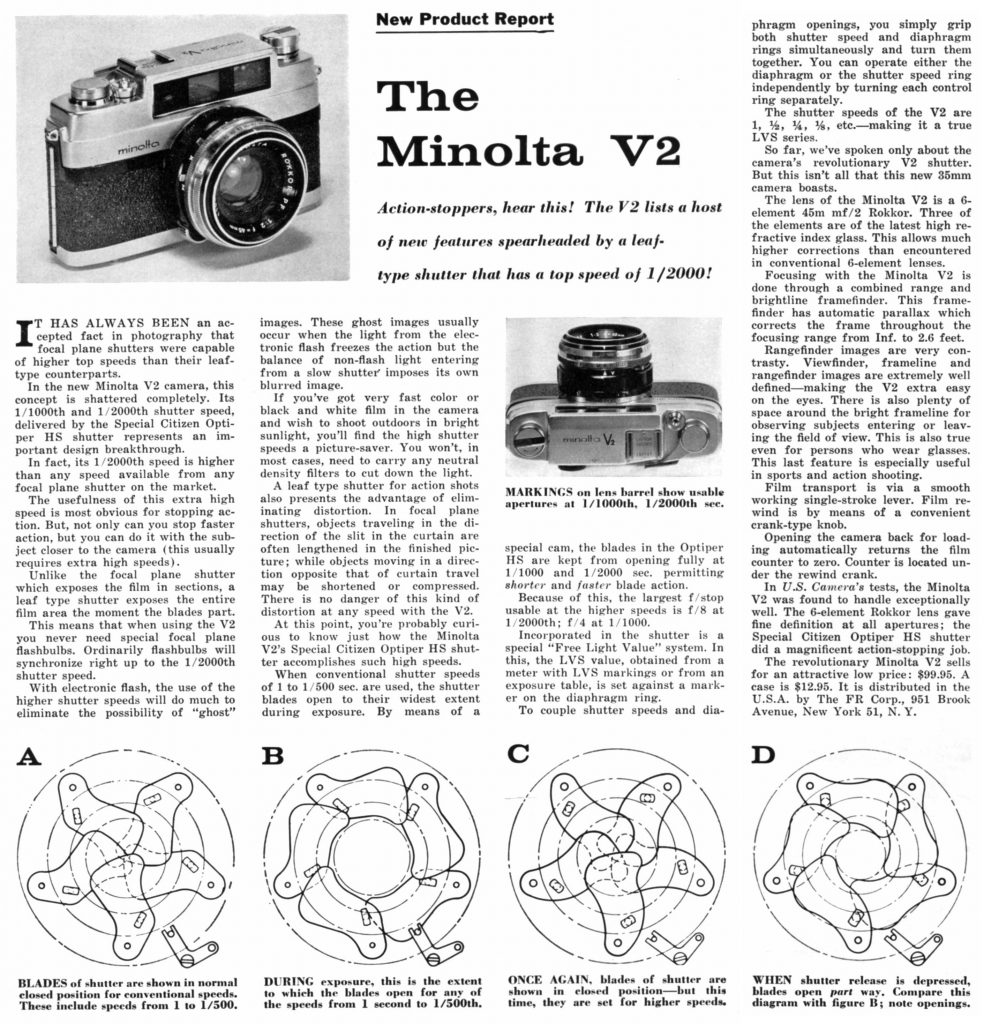

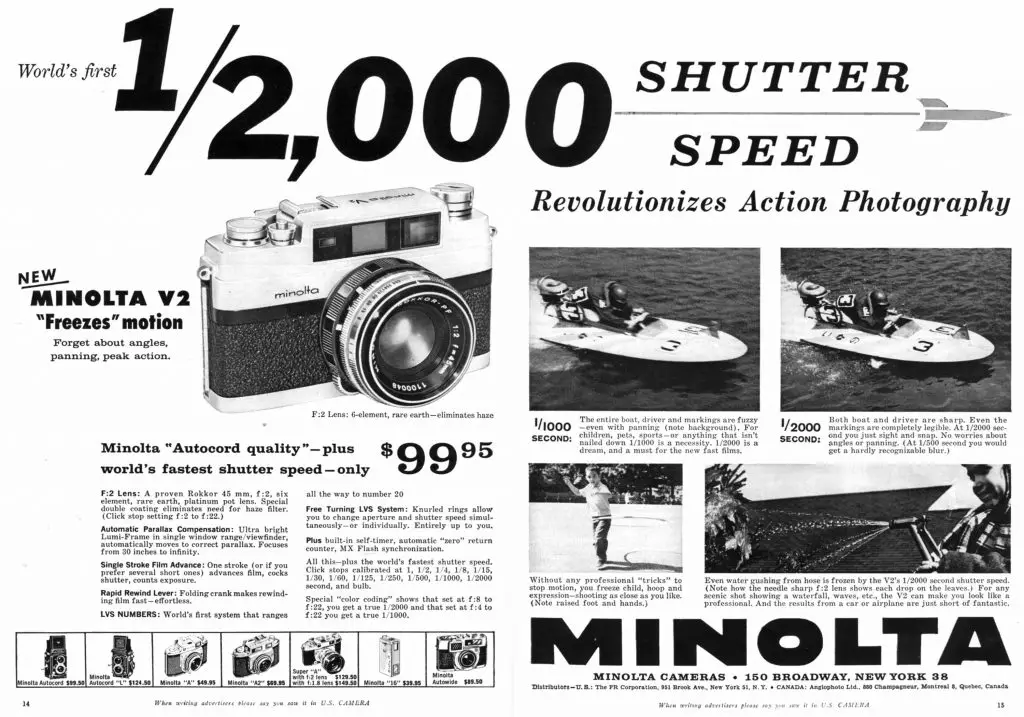

This is a Minolta V2, a 35mm rangefinder camera, produced by Chiyoda Kogaku KK starting in 1958. The V2 and the later V3 were high spec rangefinder cameras with a clever shutter design which allowed them to reach previously unreachable speeds of 1/2000 and 1/3000 seconds. Where most leaf shutter cameras are limited to a top speed of 1/500, Chiyoda found a way to angle the shutter blades at the higher speeds, limiting how far they could open to only the smallest apertures while allowing for faster speeds. Other than faster speeds, the V2 and V3 were pretty run of the mill mechanical rangefinder cameras.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2 Minolta Rokkor-PF coated 6-elements in 5-groups

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Combined Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Citizen Optiper HS

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/2000

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold Shoe with MX Flash Sync

Weight: 784 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_v2.pdf

Hey look, another Japanese leaf shutter rangefinder….yawn!

I have to imagine that was the consensus of many people by the late 1950s as hundreds of different models from dozens of Japanese camera makers filled the shelves of the local camera shops. That’s not to say these were yawn inducing cameras as most models from that era were pretty good. Canon, Olympus, Minolta, Konica, Riken, Petri, Fuji, Kowa, Mamiya, Taron, and Yashica all produced quality cameras with great lenses and some kind of Seiko, Citizen, or Copal leaf shutter, usually covering speeds 1 second to 1/500.

Although focal plane shutter cameras of the era regularly hit 1/1000 with some knocking on the door of 1/2000, it was rare to see a leaf shutter go beyond 1/500, but that was OK because as a consolation, they were flash synchronized at all speeds.

Minolta, actually Chiyoda Kogaku then, was one of the first camera makers to really push the boundaries of the 1/500 leaf shutter limit when they used a high speed shutter developed by Citizen that went not just one, but two stops faster than the 1/500 limit. In order to make a leaf shutter go faster, you either need to make the blades go faster or you need to get creative by not opening it all the way.

The latter is the method used by Citizen in the Optiper HS shutter. Normally, leaf shutters have to completely open before they can begin closing, which is why they are always flash synced at all speeds since there is always a moment when all the light can pass through the lens. But with the Optiper HS, a clever design element caused them to pivot on their axis, which when they would fire, would cause more overlap, reducing the amount of time the shutter let light through. The shutter still technically opens all the way, but the amount of overlap limits the maximum aperture of the lens, meaning you cannot shoot the camera with the lens wide open. You can either have a 1/2000 shutter speed, or you can have a shutter that allows you to shoot wide open, but not both.

When it went on sale in 1958, the Minolta V2 generated quite a bit of buzz as it was the first 35mm camera of any kind, leaf or focal plane shutter, to have a 1/2000 top speed, beating Konica with the F and Canon with the Canonflex R2000 by over a year. Each of the two previews from both Popular and Modern Photography cover the fast shutter, with the Modern article showing an illustration of how the blades work to achieve the highest speeds.

When it went on sale, the Minolta V2 carried a retail price of $99.95 which was quite a bargain considering features like a high quality 6-element Rokkor f/2 lens, automatic parallax correction, rapid film advance, and what Minolta claimed to be the first camera with an LVS that goes to 20. This price when adjusted for inflation compares to around $940 today.

Putting aside the shutter, the Minolta V2 worked and functioned like most other Japanese rangefinders of the day. The top plate had a familiar rewind knob with folding crank, there was a hot shot, a film advance lever, and cable threaded shutter release.

Around back was a film reminder dial and the opening for the viewfinder, and on the bottom was a 1/4″ tripod socket and rewind release button.

Loading film is also just like most other cameras. Lift up on the door release on the camera’s left side, and the right hinged door swings open. Film transport is from left to right onto a single slotted take up spool. The metal film pressure plate has large dimples to help reduce friction as film passes over it.

The controls for the Minolta V2 are much like that of many other leaf shutter cameras. The focus ring is nearest the body with an aperture and shutter speed ring sandwiching a rectangular window showing EV numbers. Like many cameras of the era turning one ring moves the other to maintain an appropriate exposure value, but unlike other cameras in which selecting a different combination requires contorting your fingers to release some kind of lock, on the V2, its easy to override by simply holding one ring from moving while turning the other.

By far, the most interesting thing of the shutter’s controls are the short blue, and even shorter red lines next to the EV numbers. These lines indicate the range of f/stops that can be used with the shutter’s 1/1000 and 1/2000 speeds. The blue line corresponds with 1/1000 and allows you to choose f/4 through f/22, and the red line corresponds to 1/2000 and allows you to choose f/8 through f/22. This is a side effect of how Citizen was able to achieve such high speeds, as by not requiring the blades to fully open to f/2, they can begin closing faster than otherwise possible.

The Minolta V2 has a good, but ordinary viewfinder featuring projected frame lines with automatic parallax correction and a rectangular rangefinder patch. On this example, the rangefinder patch was very difficult to see, which is likely a result of age. Most likely when this camera was new, it would have had much more contrast.

Unfortunately, I did not get a chance to shoot the Minolta V2. Actually, I have two of them and neither work. I’ve been sitting on these cameras both since 2018 hoping that one day a working example would come my way, and that hasn’t happened yet. That’s not to say I couldn’t just go on eBay and buy a third one and hope for the best, I just never did it.

The good news is I’ve shot enough 1950s Minolta cameras to know that the results likely would have been very good. The 6-element 45mm f/2 Minolta Rokkor-PF lens looks to be the same one as on the Minolta AL which I did shoot and the images turned out great.

There is no doubt in my mind that anyone willing to plunk down a C-note for one of these cameras back in 1958 would have been thrilled with it’s excellent lens, fast shutter, and ergonomics. I can’t say with any level of certainty that just because I am 0 for 2 with the Minolta V2, that it is more or less reliable than other cameras of it’s era.

I am certain that at least a few people who will eventually read this review will have a working one in their collection and tell me it is a good camera worth seeking out, and I am sure I would be saying the same thing if I had a working one.

But I don’t. Instead, I have two dead Minolta V2s and it’s time for me to move on.

If you want to read a review for the Minolta V2 by someone whose actually shot one, check out this excellent write-up by James Tocchio at casualphotophile.

Petri Flex 7 (1964)

This is a Petri Flex 7, a 35mm SLR camera produced by Petri Camera K.K. starting in 1964. The Petri Flex 7 was Petri’s top of the line camera at the time featuring a large round CdS exposure meter prominently located on the front surface of the pentaprism. The camera offered match needle exposure, a full range of shutter speeds, a good selection of lenses, and other modern features like automatic diaphragms, automatic film counter reset, and a self timer. Like other Petri cameras, the Petri Flex 7 was an economic choice that offered similar features, but for less. Sadly, a poor reputation of the company and cameras that often broken down, the camera did not sell in large numbers and is difficult to find in working condition today.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/1.8 Petri CC Auto Coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Petri Breech Lock Bayonet

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism w/ Viewfinder Match Needle

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell

Battery: 1.35v Mercury PX625

Flash Mount: Cold Shoe w/ FP, X Sync Port

Weight: 955 grams (w/ lens), 739 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/petri_pdf/petri_flex_7.pdf

I haven’t had the best luck with Petri cameras. Don’t get me wrong, I like them, and I want to use them, but it seems of any Japanese camera maker Petri has the poorest track record of cameras that can be used today. While judging a company on their inability to make products that survive over half a century probably isn’t fair, there’s quite a number of stories of Petri cameras failing back when these were sold new.

When they were called Kuribayashi prior to 1962, many of the company’s cameras were quite good. Early Petri rangefinders along with folding Kuribayashi branded cameras like the Karoron were comparable to the best Japanese camera makers but at one point, their quality control started to suffer.

While some Petri rangefinders like the Color Corrected Super are quite good and suffer the rigors of time equally to other Japanese rangefinders, it seems Petri’s SLRs don’t hold up quite as well. Starting with the company’s first attempt, the 1959 Petri Penta is also hard to find working today. The one example I have reviewed would fire it’s shutter but only after having to double wind the film advance, which is not supposed to happen since it’s a single wind camera. Even after firing the shutter, the speeds were all over the place and the curtains weren’t traveling at the right speed to get evenly exposed images.

No matter, I mounted the excellent Petri Orikkor lens to a different M42 screw mount camera and took some test shots. After switching to Petri’s own breech lock bayonet lens mount with the next model, quality control didn’t seem to improve as I’ve had trouble with every other Petri SLR I’ve handled, including the Petri Flex V which stopped working three quarters of the way through my one and only roll. I’ve come across many other Petri SLRs over the years, all of which had some sort of problem preventing it’s use. When I had the chance to pick up a nice looking Petri Flex 7, I was prepared for trouble, well, that’s what I got.

The Petri Flex 7 made it’s debut in 1964, and despite the number 7 in the name, was Petri’s 5th SLR overall. Most likely, the number 7 was chosen to coincide with Petri’s then current Petri 7 rangefinder. When it went on sale, it carried a retail price of $189.50 with a Petri 55mm f/1.8 lens. When adjusted for inflation, this price compares to about $1670 today.

The Petri Flex 7 was the company’s first SLR with an in-body exposure meter. Other cameras in the Petri Penta series had an available clip on accessory meter, but nothing built in. There are two name variants of the Petri Flex 7, with most of them having “Petri” and “Flex” as two separate words, but there were a small number called the “Petriflex 7”.

When it was sold, it carried a retail price of $189.50, which compares to around $1660 today. In the ad to the right, we see the camera with a black bezel around the lens mount and meter, which to my knowledge was never built, suggesting early prototypes might have looked different.

By far, the most striking feature of the Petri Flex 7 is the large CdS exposure meter on the front face of the pentaprism, right above the lens. I am unsure if this was intentional, but this look is very similar to the large round meter in the same location of the Zeiss-Ikon Contarex. The Contarex was an extremely expensive and high quality camera that first hit the market in 1960, so it stands to reason that Petri intentionally mimicked the look to suggest a sense of luxury for their model, or perhaps it was just a coincidence.

Beyond the meter, the Petri Flex 7 is a large and hefty camera. Weighing 955 grams with the included 50mm f/1.8 lens or 739 grams without, the Petri Flex 7 body is on par with a Nikon F2 with the DE-1 “standard” prism.

The tall and flat top of the meter and the broad shoulders of the rest of the top plate give the camera an oversized look, which until you get into your hands, isn’t as bad as it shows in pictures.

Most of the Petri Flex 7’s controls are in the same locations you’d expect to see them on other SLRs. The rapid rewind knob is on the left, next to the top plate match needle (which on my example was missing a top cosmetic piece). The large pentaprism has an accessory shoe on top, and to it’s right is a large shutter speed dial, rapid film advance lever, and finally the automatic resetting exposure counter.

There’s not much to see on the back or the bottom other than the opening for the viewfinder, rewind release button, and centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket.

As with every Petri SLR made between the original Penta and the FTX, the Petri Flex 7 uses the Petri breech lock bayonet lens mount. If you’ve ever used a manual focus Canon SLR with the FL/FD mount, the one here works the same way. Align a red dot on the lens with one on the mount and turn the metal collar attached to the camera and that’s all. It’s quite quick once you get used to it, but not having to rotate the lens while mounting and dismounting is a little strange for someone not used to it.

While Petri’s quality control of their cameras may be in doubt, their lenses are quite good. Images shot with Petri lenses on working cameras consistently come out as sharp and well defined as those from any number of other makers.

Loading film into the camera is a normal affair. Release the door lock using the latch on the camera’s left side, and the right hinged door swings open. Film transport is from left to right onto a single slotted, fixed take up spool. The metal film pressure plate is large and covered in dimples to help reduce friction as film passes over it.

While most of the Petri Flex 7 works like many other 1960s SLRs, it is not without it’s oddities. The most glaring is that due to the location and large size of the CdS meter, it’s location completely block the aperture ring on the lens when looked down at from above. You have to tilt the camera almost up to the sky to see which f/stop you’ve selected.

Realizing this ergonomic snafu, Petri added a second “F-window” above and to the right of the lens mount showing a duplicate of what aperture is selected. In the gallery above you can see the camera is set to f/5.6.

The Petri Flex 7 supports open aperture metering which requires the camera body to know both what the maximum aperture of the lens is, along with whatever you have selected and in order to do that, it uses an external coupling via a pin on the lens itself, which slides into an aperture arm on the camera’s body. Other camera makers like Miranda used a similar external coupling and they all work reasonably well, in that on the Petri, the pin is spring loaded which allows it to pop in and out of the arm as you mount it.

Also like other camera makers, Petri went with an angled shutter release on the front plate of the camera. I find that these types of front releases are very comfortable and somewhat improve stability when firing the shutter as inward pressure is directed towards your face, which when the camera is already up against your face, resists body shake like a top plate shutter release sometimes might have.

Up front, we also see the 10 second mechanical self timer, a flash sync port, and the round opening for the mercury battery that powers the meter.

The Petri Flex 7 had a reasonably bright viewfinder which used a Fresnel pattern to even out the light across the frame. Shooting outdoors with the f/1.8 lens and there is little to no vignetting and I had no problem achieving sharp focus while using prescription glasses.

A large microprism circle is in the center for sharp focus, along with a lighter color ring to indicate the metered area. A match needle display in the bottom right corner is used for proper exposure.

The Petri Flex 7 had a competitive feature set compared to other mid level SLRs of the era like the Minolta SR-7 and Yashica J7 which now that I write that, could be another reason Petri called it the ‘7’ to compete with other similarly featured models. Whatever the case, the camera itself should be a fine photographic tool, that when combined with Petri’s excellent lenses would produce excellent images.

Except that this being a Cameras of the Dead article, we’re talking about a non working camera. I tried everything I could, from opening the bottom plate and trying to liberally lube everything to trying “percussive persuasion” on the camera’s various parts to no avail. The camera was dead, and from talking to other collectors, it seems like more Petri Flex 7s are dead than working, so I didn’t even bother trying to find another.

The Petri Flex 7 had a good feature set for it’s time, had a good selection of lenses, and a distinct look, but for this one, looking at it is about all that it’s good for as this one’s a goner.

Yashica Sequelle (1962)

This is a Yashica Sequelle, a motorized half frame camera that had a unique looking body similar to that of a motion picture camera. The camera was capable of continuous exposures via it’s electronically driven motorized film transport. The camera used three AA “pen light” batteries to power the film transport, making it one of the first cameras to use a battery powered electric motor. It featured an uncoupled selenium exposure meter which required the user to set the exposure based off EV numbers on the meter. The camera was designed to be simple and did not have a focus scale, instead used zone focus icons that would appeal to the novice photographer. The Sequelle was a short lived model which is very difficult to find today, and even more difficult to find in working condition.

Film Type: Half-Frame 135 (35mm)

Lens: 2.8cm f/2.8 Yashinon Coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 2.5 feet to Infinity, Numbers unmarked, Zone Focus Icons Only

Viewfinder: Flip-Up Scale Focus

Shutter: Seikosha-L Leaf Shutter

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/250 Seconds

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Meter

Battery: (3) 1.5v AA Batteries

Flash: PC Sync Port, 1/30 Flash Sync

Weight: 744 grams (w/ batteries)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/YashicaSequelleManual.pdf

Now here’s a weird one. Back in September 2019 when I did the review of the Taron Chic, I was already aware of the similarly styled, vertical half-frame Yashica Rapide. In fact, the Rapide had been on my want list before I even knew the Chic existed, but as fate would have it, the Chic would arrive at Mike Eckman dot Com headquarters first and would receive a full review. It was a fun little camera, and I thought that if I ever could find a Rapide, I could do some kind of head to head competition between the two.

It is now October 2021, and I still don’t have a Rapide, but I do have Yashica’s other vertical half frame Sequelle. As best as I can tell, the Sequelle is less common than the Rapide, at least based on the number of them that appear for sale on eBay, but sometimes this is how things turn out.

The Sequelle is one of the more odd cameras I’ve ever come across as it has a unique combination of features. For starters, the overall look of the camera was meant to resemble motion picture cameras that were common of the time. When it was new, the Sequelle would have come with a handle that when attached to the bottom of the camera, allowed it to be used one handed. Most examples of this camera, including mine, no longer have the handle. but with it, the camera was likely easier to use single handed as in the Japanese ad to the right.

The film transported vertically, exposing “half frame” 18mm x 24mm images. In other cameras like the Olympus Pen which shoot half frame images in a standard left to right transport, the images have a natural portrait orientation, and you must rotate those cameras 90 degrees to get a familiar landscape orientation. With vertically traveling cameras like the Sequelle, and previously mentioned Rapide and Taron Chic, the film is already turned 90 degrees, which means that under normal use, your images are already in a landscape orientation.

When it went on sale in 1962, the Sequelle joined the Iloca Electric (rebadged as the Graflex Graphic 35 Electric in the US) and KW Prakti as the only still cameras using an electric motor powered by AA batteries. It sold in the United States for “under $80” which probably means $79.50 which when adjusted for inflation compares to around $715 which would have likely been a pretty big stretch for the family snap shooter looking for a simple to use, but high quality camera.

The Sequelle is a unique looking camera that on paper probably seemed very cool, but in use, likely didn’t appeal to many. The camera does not appear to be produced for long as I found no references in magazines or in any advertisements after 1962. In addition, finding copies for sale online is very difficult. As I write this in August 2021, there are only 3 for sale on eBay, with asking prices ranging from $98 to $569.99.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the Sequelle was it’s electrically powered motorized film transport. Motorized cameras had been around for quite some time before the Sequelle, but most of them used some type of clockwork spring that needed to be wound up and then when the shutter was activated, the mechanism would unwind enough to fire the shutter, advance the film, and cock the shutter for the next shot. The Sequelle took it one step further, allowing for continuous shooting at a rate of two frames per second by simply holding down the shutter release. Unlike a clockwork motor that would eventually need to be wound up again, the battery power meant that you could go through an entire roll of film in one continuous shot if you so chose.

Targeting the novice photographer who likely already knew how to use an 8mm or 16mm motion picture camera, the Sequelle included an uncoupled selenium exposure meter with a LV scale allowing for easy calculation of exposure. Although featuring a full focus lens, focus distances were not marked on the lens, rather three zones which represented close-ups, groups, and scenic shots. The large depth of field afforded by the wide angle Yashinon 2.8cm lens meant that in most situations, focusing the camera would not be a challenge. Continuing with a simple theme, Yashica wisely went with a flip up optical viewfinder, which has the advantage of keeping costs low, while offering a large and bright viewfinder experience. Had the camera came with some kind of through the body viewfinder, it likely would have increased cost and complexity.

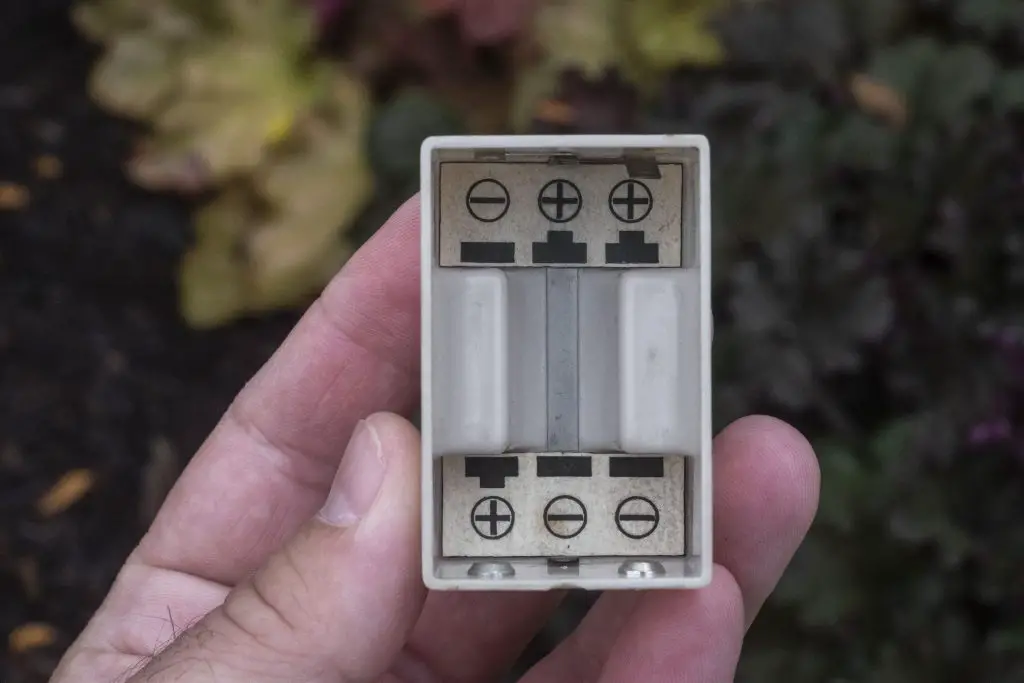

On the back of the camera is a large door where you’d likely expect the film compartment to be, but is actually an opening for the battery pack. Inside is a plastic box with a lid that when removed has room for three AA batteries. In the era this camera was built, AA “pen-light” batteries were zinc-carbon dry cells, which didn’t last very long, so owners of these cameras likely had to replace them often. When alkaline batteries became more common in the late 1960s, the life span would have been dramatically increased.

With the battery compartment taking up a large amount of space, film is loaded through the side of the camera. By flipping a metal lever on the camera’s left side and twisting it to release a lock, the entire left side of the camera comes off to reveal the film compartment. A standard 35mm cassette drops in on one side and a special Sequelle take up spool on the other. In order to load film, you needed to thread the film leader onto the take up spool with it out of the camera, and then drop in both the supply cassette and spool at the same time, similar to how it’s done on a bottom loading Leica.

The next step in loading the film is to reset the subtractive exposure counter which counts backwards, showing how many exposures remain on the roll. Since this is a half frame camera, you’ll get roughly double the number of exposures of whatever length of film you installed. Strangely, the counter stops at 68, not 72, which suggests that perhaps the camera uses more of the leader than usual.

When the exposure counter reaches zero, the word STOP appears and the motorized drive is deactivated. This is a safety measure likely to help prevent the motor from continuing to run at the end of a roll, possibly tearing the film out of the cassette or burning out the motor.

The motorized film transport only goes in one direction, which means at the end of a roll, you must disengage the coupling by pressing a chrome button on the camera’s right side, and manually rotating the rewind knob with flip out handle until the film is completely wound back into the cassette.

Of the three cameras in this, the 10th edition of the Cameras of the Dead, the Sequelle is the one I wanted to use the most. Sure, Minolta V2’s top 1/2000 shutter speed, and the Contarex style of the Petri Flex 7 are worthy of a roll of film or two, but the battery powered vertically transporting half frame motion picture style Sequelle is the one that checked off the most “quirky camera” boxes for me.

The seller I bought it from clearly stated it didn’t work, but I still had hope that perhaps they just didn’t know how to use it, or maybe the battery contacts had corroded, or there was some obvious loose wire that I could solder and make it work. But sadly, nothing I did made any difference. I used a Fluke multimeter and confirmed proper voltage at the battery connections with three fresh batteries, I scoured the Sequelle’s user manual hoping I’d find some hidden kill switch that would magically make it work, but sadly, nothing I did made any difference.

Like so many that have come before it, the Yashica Sequelle is the not only the third dead camera in this article, it represents number 30 in the series, a number that may or may not increase…

Conclusion

This concludes the 10th Cameras of the Dead post which means I have brought to you 30 dead cameras that I otherwise wouldn’t have reviewed because they didn’t work.

In a sort of “reverse Murphy’s Law”, each time I have included a camera in this series, my chances of coming up with a working one seems to have increased. After writing about dead copies of the Canon AL-1, Kodak Retina Reflex III, and Kowa SE-T, I managed to come across perfectly working examples of those cameras which I was able to give a full review for. In fact, I also have come across a working Kodak Signet 80 and Kiev 5 which I’ve already shot, but haven’t gotten around to reviewing yet.

When I first had the idea of a Cameras of the Dead post in August 2016, I never intended it to be a series. I didn’t even coincide that post with Halloween or “Halfway to Halloween” like all subsequent posts as I was just a way to quickly get through three cameras in a single article that I couldn’t use.

Fun Fact: In the 7th Cameras of the Dead post where the featured image is a screenshot from a Dario Argento movie, this ended up getting that post flagged by Google for having “shocking content” that restricted that post from appearing in search results or generating any ad revenue. I only make pennies off revenue on these old posts, so I never bothered to change it, but I found it amusing to see my camera review site being flagged for shocking content!

As much as I have enjoyed all of the tongue in cheek horror film references I think I’ll end this series with ten. Don’t get me wrong, I still have a LOT more dead cameras in my ‘camera graveyard of doom’ and I’ll still want to write about some of them, I’ll likely just keep it to one off posts here and there.

So, here’s to the “Final Chapter” of the Cameras of the Dead series. Will this truly be the end to my corny humor, or will Jason, err, I mean Buzzsaw be back for another round?!

Mike, What, not eve a mention of the Yashica Samurai in this note on the Sequelle and Taron Chic? How about an update on the Yashica Z2? Regards/73 –Terry

Here you go! 🙂

https://mikeeckman.com/2019/04/yashica-samurai-x30-1988/

I guess I didn’t mention it as I see that as a completely different camera. Sure, its vertically traveling, but it’s half frame, an SLR, fully automatic, and was made much later.

Cameras of the dead… the resurrection then next year eh Mike? 🙂

I have a working V2 which I am at the point of selling if you want to try it out for a while. I is pretty excellent in my opinion (there’s a short review on 35mmc).

That’s very nice of you to offer, but I think I’ll pass. Not that I wouldn’t be interested in seeing what it could do, but I have so many Minolta rangefinders, that other than the top 1/2000 speed, there’s really not much more I could say that I didn’t already say in the “dead” review. If you ever shoot some sample photos and want to send them to me as samples shot from a working V2, I’d be happy to include them and credit you though. Just let me know.

In the late 1960’s, I sought to have X synchronization added to Ye Olde Leica IIIa, since it was rhe only 35mm camera that (sorta) couldn’t be “used after sundown.” This led me to an independent camera repairman who had very strong opinions on certain camera brands. He warned me away from Petri 35m SLRs, declaring that their mechanical innards were better suited to a Lionel model train than a camera!

He also had a low opinion of Miranda 35mm SLRs, preferring to use his time to work on the likes of Leitz, Zeiss or Rollei 120 cameras.

I did come across a Petriflex 35mm SLR which worked fine, aside from occasional hangups with certain shutter speeds. I did take off the bottom cover to see what kind of gear train this camera used and found an interesting set of rods and lever assemblies unlike “the usual suspects.” (Canon/Minolta/Nikon) Keep the “Cameras of the Dead” entries going; it might save some naive camera user/collector from buying a doorstop/”cabinet/mantle queen”!;)

That’s great info! I’ve heard similar stories like yours of camera techs back then not wanting to touch Petri (and Miranda) SLRs for that very reason. It’s amazing that some work today at all!

In terms of the Cameras of the Dead series, I still still definitely write about the occasional dead camera, I just think I’ll take a break from the themed “three-fers”. 🙂

I liked your story. But dead camera’s from the sixties do not exist. They all can be repaired and woken up from the grave… euh display.. and taken out. Thats the fun of mechanics instead of electronics. All the best from Holland! Jeroen