This is a Canon Pellix QL, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made in Japan by Canon starting in 1966. It was an update to the original Pellix from 1965, adding Canon’s Quick Load film system and a sync port for an optional exposure booster. The Canon Pellix gets it’s name from a special type of semi transparent pellicle mirror that works like a normal SLR reflex mirror, but never has to flip up and down, allowing light to both reflect into the viewfinder and expose film at the same time. The distinct advantage of a pellicle mirror is that there is never any viewfinder blackout when the shutter is firing. This does come at the expense of viewfinder brightness however, so to combat that, Canon introduced with it a fast 58mm f/1.2 lens to maximize brightness. The Canon Pellix is historically significant, but wasn’t produced for long as further advancement of SLR viewfinders and shutters rendered the advantage of the pellicle mirror obsolete.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 38mm f/2.8 Canon FLP coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Canon FL Breech Lock Bayonet

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, X, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ Viewfinder Match Needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and FP and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Viewfinder Blind, Shutter Lock

Weight: 937 grams (with lens), 744 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.butkus.org/chinon/canon/canon_pellix/cannon_pellix.pdf

How these ratings work |

From the outside, the Canon Pellix looks like any ordinary 1960s Canon SLR, but the name hints at an innovative new feature that had never been used on an SLR before. A non moving semi-transparent pellicle mirror replaces the traditional moving mirror, allowing the shutter to fire without the mirror having to lift. This eliminates viewfinder blackout and is said to make the camera quieter. In use however, the Pellix doesn’t do much to differentiate it from other non-pellicle SLRs. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.8 | ||||||

History

Single lens reflex cameras existed for quite some time prior to the first 35mm SLRs from the 1930s. They served a special purpose type of photographer who needed precise composition through the taking lens without any guesswork or parallax error common with rangefinders and other non-through the lens cameras. Those early reflex cameras were very large though, so when Ihagee released the much smaller Exakta, the benefits of an SLR were now in a much smaller and portable package.

World War II disrupted the further advancement of the SLR, but by the late 1940s, with new models from KW and Zeiss-Ikon hitting the market, SLRs began a slow but steady rise to prominence. But it didn’t happen over night as those early cameras had quite a number of cons compared to other 35mm cameras. They were slow in operation, the reflex mirrors did not automatically return after each image, there was viewfinder black out at the moment of exposure, viewfinders were dark, the action of the mirror combined with the shutter was very loud, and with early waist level finders, the TTL image was reversed, further slowing down the photographer.

In the early to mid 1950s, improvements came at a steady pace with pentaprisms that corrected the image at eye level, Fresnel viewing screens that improved viewfinder brightness, auto and instant return mirrors that minimized viewfinder blackout, and lenses with automatic diaphragms that ensured the viewfinder always had the maximum amount of light without requiring the user to manually stop down the lens before each image.

With each new innovation, the SLR became more appealing to a greater number of people, and by the late 1950s, with new models from Asahi (Pentax), Pentacon (Praktica), Minolta, Miranda, and Topcon, the SLR started to take it’s place as the preferred style of 35mm camera.

Canon’s first attempt at a 35mm SLR was the Canonflex from 1959, which although it was a well built camera, the Canonflex missed it’s target audience and sold poorly. Realizing that they needed to rethink their approach to SLRs, in April 1964, Canon would release the Canon FX, and all new medium bodied mechanical SLR. Featuring a body mounted coupled CdS exposure meter and a revised FL lens mount which updated the original Canonflex R-mount with a new aperture linkage allowing for stop down exposure metering, the Canon FX was a moderate success.

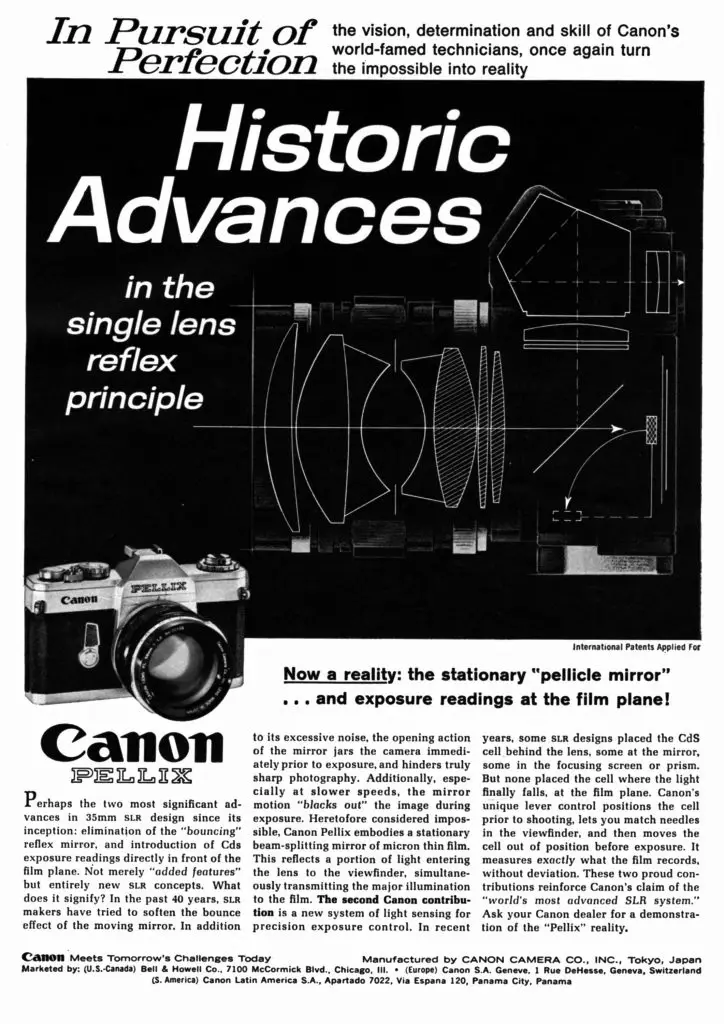

Less than a year later, in early 1965, Canon would release the Pellix, the third in Canon’s new lineup of FL-mount SLRs behind the FX and the Canon FP which had no meter at all, but Canon’s first 35mm SLR with through the lens (TTL) metering.

The Canon Pellix was released at the same time and competed against Nippon Kogaku’s Nikomat/Nikkormat FT which had a similar, but different approach to TTL metering. Unlike the Nikkormat, which placed the CdS exposure meter in the prism, the Pellix placed the meter on a hinged arm that when activated by pressing the self-timer lever towards the lens mount, flipped up and took a reading from directly in front of the film plane.

Placing the meter in front of the film plane and behind the reflex mirror was a challenge as the reflex mirror would block the light needed to take a reading. This was a problem that Tokyo Kogaku solved with their Topcon RE Super from 1963 which also had a meter behind the mirror, by cutting narrow slits into the reflective surface of the mirror, allowing 7% of the light to pass through to the meter.

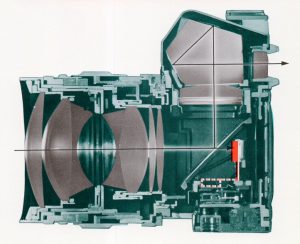

Canon’s approach was to use something called a pellicle mirror which was a 0.02mm thin Mylar plastic membrane coated with a semi reflective zinc sulfide layer that would allow light to both pass through and reflect off of it similar to a beamsplitter in a rangefinder camera. Pellicle mirrors had been used in photography since the late 1930s in color separation cameras such as the Devin Tricolor Camera which used two pellicle mirrors along with three color filters which would split the image into separate monochrome red, green, and blue exposures. These three exposures could later be combined back together to form a full color image.

The Pellix’s mirror does not evenly split the light 50/50 between the viewfinder and shutter as some sites online suggest. In reality, the split is 30/70 to the viewfinder and shutter. With only 70% of the light from the lens reaching the shutter, you effectively lose 2/3 of a stop of light, meaning that with an f/1.4 lens mounted, the same amount of light reaches the shutter as if you had an f/1.8 lens mounted. To the viewfinder, the loss is greater, resulting in an equivalent of having an f/2.2 lens with the f/1.4 mounted. This loss of light in the viewfinder is certainly noticeable, but not exactly a deal breaker, in fact, in bright light, the brightness of the viewfinder doesn’t look that much different from most other SLRs from the same era.

One additional challenge Canon faced with the Pellix, was that in a normal focal plane shutter SLR, the reflex mirror protects the shutter curtains from extra light, which if the lens is focused to infinity and the camera is exposed to direct sunlight, can burn holes into the curtain material. This was a challenge faced by rangefinder cameras who had no such protection from a mirror. With the Pellix, Canon solved this problem in the same way later rangefinders like the Nikon SP and Canon P did, by using titanium metal curtains which resisted holes from burning through the curtains.

With their new TTL meter that took a reading at the film plane, pellicle mirror, and metal shutter curtains, the Canon Pellix offered one additional benefit, which was that without the need for a moving mirror, it could support SLR lenses that would normally be obstructed by the mirror. SLR Lenses such as the 2.1cm f/4 Nikkor-O and 21mm f/4.5 Carl Zeiss Biogon both required the reflex mirror to be locked in the up position before being mounted and the use of an auxiliary viewfinder for composition. This allowed Canon to design two additional lenses for the Pellix, an ultrawide 19mm inverted telephoto f/3.5 and a “For Pellix Only” 38mm f/2.8 lens which not only wouldn’t interfere with the mirror, but could would not have required an auxiliary viewfinder.

The original Canon Pellix was only available for a year before it was replaced by a similar, but improved model called the Pellix QL which added Canon’s new Quick Load film system that had made it’s debut a year earlier in the Canonet rangefinder series. Canon’s QL system was quite good, and worked very well. To use it, you simply opened the film door, extended the leader to a red mark in the film compartment without having to attach anything to a take up spool, and then close the door. The QL model also added two additional features, the first was a lock on the self timer lever which kept the meter on and the lens stopped down without having to hold your finger on it, and the option for an accessory low light Canon Booster which connected to two holes in the battery compartment and allowed the camera (and Canon FT QL which it was compatible with) to meter in lower light down to -4.5EV.

With all the new technology in the Pellix, photography magazines like Modern and Popular Photography eagerly awaited their chance to get their hands on a copy to review. A large number of reviews were written shortly after it’s release including the four below.

The first one is from the August 1966 issue of Modern Photography and is a joint review of the later Canon Pellix QL and the non-pellicle FT QL. This review is the most interesting of the three as it gives a true A/B comparison between two very similar cameras, showing how the pellicle feature compares to one without it. As an aside, I found it interesting that at the top of the second page, the editors at Modern state that they heard no audible reduction in noise from the Pellix, despite the lack of a moving mirror. This is in contrast to the last review which states that the Pellix is significantly quieter as a result of the non moving mirror. As you’ll read later in this review, my experience has been that the Pellix is just as loud as a non-pellicle SLR.

The second and third articles below are from the time the original Pellix was released and are both from Modern Photography offering a preview of the new model along with the Nippon Kogaku Nikomat, and an early quick review, offering some technical explanation for those readers at the time who wouldn’t have ever heard of a pellicle mirror.

This final review claims to be from Popular Photography’s April 1968 issue, but is very clearly a Bell & Howell promotional pamphlet that seems to have a heavy bias in it’s favor, which could perhaps explain why this is the only reference to the Pellix being a quieter camera.

Edit 10/18/2022: After publishing this review, I stumbled upon an article in Jason Schneider’s Camera Collector column from the September 1980 issue of Modern Photography looking back at the Canon Pellix. As he usually does, Schneider gives a quick intro to the camera, offering up some specs, and his thoughts on it’s use and why someone might want to add it to their collection. Although not technically a contemporary review, this look back on the Pellix was written only 15 years after the camera’s release.

A price for the original Canon Pellix is not mentioned in any of the articles or ads I found, but it stands to reason it would have been pretty close to the Nikkormat FT’s $270 price. The later Pellix QL’s price is given as $299.95 with f/1.8 lens, $349.95 with f/1.4 lens, and $384.95 with Canon’s all new f/1.2 lens. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $2625, $3050, and $3365 today, making the Pellix a rather expensive option, only afforded by those who wanted to most cutting edge of technology in their cameras.

The Canon Pellix was an interesting and innovative SLR when it was first released, but compared to the very similar Canon FT QL which was available at the same time, it offered little to justify it’s higher price tag and it was discontinued after a short while. Canon and it’s competitors found that a more traditional approach of placing the meter in the prism worked well enough. For companies like Tokyo Kogaku and Olympus who placed swing up meters in the film plane, they found that the simpler method of making thin transparent strips in the reflective surface of a traditional mirror worked just as well, without having a noticeable impact on mirror brightness.

Canon would once again use a very similar pellicle mirror concept in a special high speed version of the Canon F-1 developed for the 1972 Montreal Olympics, which when combined with a specially made motor drive, could shoot at a speed of 9 frames per second, much faster than anything available at the time. In 1984, a second pellicle mirror equipped high speed version of the New F-1 achieved a blistering 14 frames per second making it one of the fastest 35mm cameras of all time. Both Canon and Nikon would experiment with the technology, releasing pellicle mirror equipped special editions of some cameras in their EOS and F2 lines.

In 2010, Sony would once again employ pellicle mirrors in a series of hybrid mirrorless/SLR digital cameras, which they referred to as SLT (Single Lens Translucent) cameras. The idea was to create a DSLR like camera that lacked an optical viewfinder, instead using an electronic only viewfinder that would reflect a portion of the light normally passing to the digital sensor to a phase detection autofocus sensor. This style of camera was said to offer faster and more accurate auto focus, along with the benefits of an EVF in a traditional DSLR style camera.

Although the history of the Canon Pellix stands out as an anomaly in the history of SLRs, to call it a failure isn’t fair. For starters, the pellicle mirror did it job exactly as designed. The loss of some light in the viewfinder was only an issue in dark spaces, the meter easily compensated for the 1/3rd stop of light, and compared to SLRs with traditional mirrors, the Pellix was capable of the same high quality images. Apart from the lack of viewfinder blackout, shooting a Pellix is indistinguishable from that of other SLRs of the same era.

Today, the Pellix is sought after by collectors who like things that were different. No one else made a mass produced pellicle mirror SLR like this, so whether you are a dedicated Canon collector, or just like unique cameras, the Pellix deserves a spot in any collection. Be forewarned though, that for reasons I’ve never been able to discover, used Pellixes tend to suffer from foam degradation in the prism at a rate worse than that of other SLRs of the era, so if you are considering buying one to use, be sure to check the prism first.

My Thoughts

For the longest time, I had no interest in reviewing the Pellix. Although the pellicle mirror concept is cool, the rest of the camera is just a standard Canon SLR to which there’s already quite a bit written online about.

It wasn’t until one day I was visiting Robert Rotoloni’s house and he had this nice Pellix sitting there with the incredibly rare 38mm FLP lens attached to it, that I picked one up and began to see the appeal. I asked Robert if I could borrow it and he said sure. He was trying to sell the camera, but said I could hold onto it until he found a buyer.

Externally, the Pellix is nearly indistinguishable from the later Canon FT QL, but the camera was actually built on the body of the earlier Canon FX. Whichever camera you have, the Pellix shares nearly all the same controls, dimensions, and weight with that era of Canon SLRs.

On the top plate, starting from the left is the folding rewind knob, with a viewfinder blind dial beneath it. This feature is unique to the Pellix as it is used to block light from entering the viewfinder eyepiece during long exposures. The reason this is necessary is that since the reflex mirror is transparent, light can enter the eyepiece, pass through the prism, and down into the mirror box, reaching the CdS meter, causing erroneous readings. During short exposures when the photographer’s face is up to the eyepiece, this is less likely to happen, but if the camera is on a tripod or if you are doing extended exposures, it is recommended to close this blind before making the exposure.

Above the prism is an accessory shoe for things like a flash, or the optional Canon Booster which is made for the Pellix and the FT QL.

Off to the right is the combined shutter speed and film speed dial. Changing shutter speeds is just a matter of rotating the entire dial, but changing film speeds requires you to lift up on the outer chrome ring and rotate just the outer part. You cannot go from B to the X setting, as there is a “wall” between those two settings.

Next is the cable threaded shutter release with a rotating shutter lock below it, the rapid film advance lever, and automatic resetting exposure counter.

Flip the camera over and the bottom has the rewind release button, centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, and the rotating key for releasing the film door as the Pellix predates the common use of lifting the rewind knob to unlock the door. Also note that this key is not like those on earlier cameras in which rotating the lock also opens and closes “Leica style” reloadable film cassettes. This lock just opens the door, and nothing else.

Around back, the Pellix has a black plastic frame around the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder which is grooved to support a couple of different viewfinder attachments.

On earlier Pellixes like the camera I have here, the back of the camera also has an engraving that says “Canon Camera Company, Made in Japan” along with the serial number and a round disc to the left of the viewfinder that does not do anything. Both this engraving and that disc disappear on later Pellixes. In my collection, I also have Pellix with a serial number 165051 which lacks both that small disc and the rear engraving. Instead, the serial number is engraved into the top plate to the right of the rewind knob.

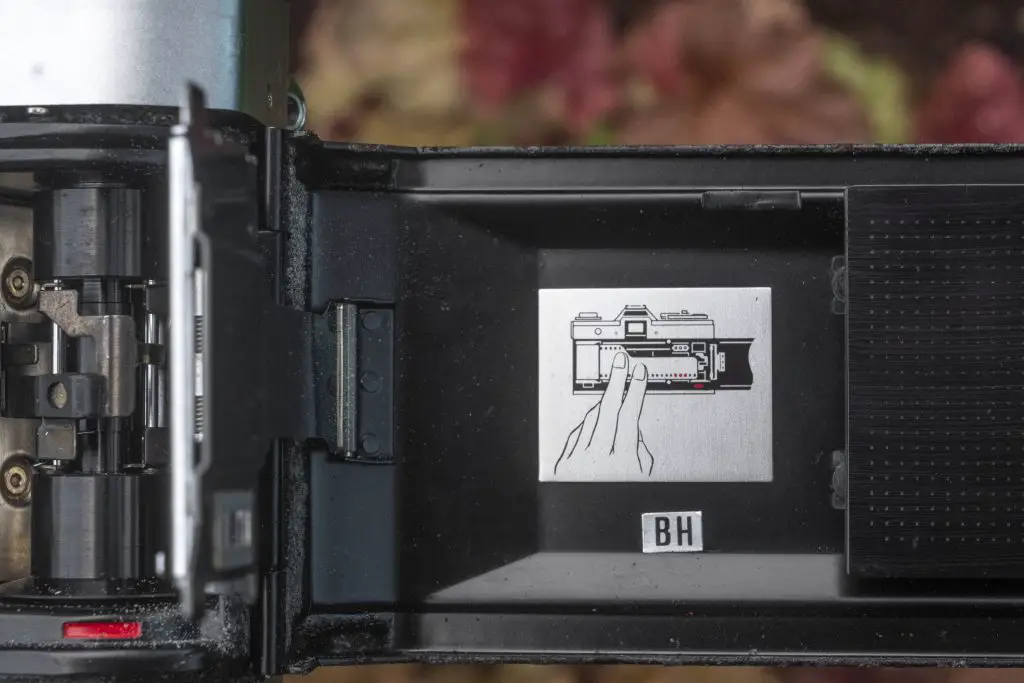

With the film door open, we see Canon’s excellent Quick Load system which was not present on the original non-QL Pellixes. Film transport is from left to right into the Quick Load system. Although entirely mechanical, it works similarly to automatic film load systems which would become common in the 1980s. When loading film, simply extend the leader to the red mark in the bottom right corner and close the door. The folding metal frame guides the film into a central shaft and upon winding the camera a couple of times, the film leader is automatically attached.

Canon’s implementation of this system works extremely well, and in my opinion is one of the single greatest innovations the company made during this era. While I woudln’t go as far as to say that I’d buy a camera based entirely off how easy it is to load film, no one else in this era had anything close. I’ve used Canon’s QL system on other cameras that offered it, including the Canon rangefinders, and it always worked on the first time, every time.

As for the rest of the film compartment, we see a dimpled and oversized film pressure plate which helps to reduce friction on film as it transports through the camera, and a sticker on the inside of the door to help remind you how the Quick Load system works.

On the camera’s right side, we see the opening for the PX625 battery, which normally wouldn’t be that interesting, except when you unscrew the cap and look inside, you’ll notice two little holes which are connection points for the optional Canon Booster which was available for the Pellix QL and FT QL. With the booster connected to these two holes, the camera and booster are powered by two PX625 cells in a secondary battery compartment on the booster itself, somehow altering the voltage of the camera’s meter, giving it five additional stops of metering down to -4.5EV.

Up front, the Pellix has what looks to be a rather large self timer lever. This style lever is also found on the Canon FT QL and the reason for it’s size is that it serves dual purpose as both the self timer, but also the stop down/meter activation switch. Pull the lever back for a mechanical 10 second delayed action timer, but press it towards the lens mount and the lens will stop down to your chosen f/stop and give you a meter reading. Canon SLRs would not support open aperture metering until the release of the FD mount with the Canon F-1 so the lens must be stopped down before an accurate meter reading can be taken.

The Pellix uses the Canon FL lens mount, which is physically similar to, but not identical to the earlier R mount used on the Canonflex and the FD mount.

All Canon R, FL, and FD mount lenses use a breech lock bayonet, in which each lens has a rotating collar that locks the lens to the body of the camera when mounted. Unlike a standard bayonet mount used by most other SLRs in which lenses are attached or removed by physically rotating the entire lens a certain degree from top dead center, with the Canon breech mount, the lens never physically moves, only the collar does. When this system was first created, the perceived benefit was that as you attach or detach a normal bayonet, the rotating motion of the lens against the camera body could eventually wear it down, altering the flange distance. With the breech lock, no part of the lens rubs against the camera body.

Whether or not over the course of a normal camera’s life, this ever made any difference is debatable, but that was the theory. Over the years, there have been many critics of Canon’s breech lock system (myself included) who point out that mounting the lens is slower, can result in stuck lens caps, and exposes the linkages of the lens, but the reality is, Canon’s lens mount isn’t worse, it’s just different, and I suspect that a large number of people who used these lenses over the years, never had a problem with them.

Lens mount aside, the most interesting thing about the lens mounted to this Pellix, is that it is the uncommon 38mm f/2.8 Canon FLP lens. This was one of only two FLP lenses that were marked “For Pellix Only” because the rear lens element protrudes into the mirror box, and on SLRs with a moving mirror, would hit the mirror as it moved. This lens could be used on a non-Pellix if it had a lock-up mirror feature, however you’d still need to use an auxiliary viewfinder as the locked up mirror would prevent use of the pentaprism which isn’t a problem on the Pellix.

The biggest oddity with the FLP lens however is that it doesn’t really offer much of a benefit other than being more compact than a typical ~35mm wide angle Canon FL mount lens. Combing the somewhat slow f/2.8 maximum aperture of the FLP lens with the Pellix’s dark viewfinder, composing with this lens attached is quite dark, especially indoors.

With all of the talk about the Pellix mirror only passing 30% of the light entering the lens into the viewfinder, it’s quite surprising to see how bright it is. The focusing screen is bright corner to corner with no obvious vignetting or distortion near the edges. In the center is a small microprism circle which works, but I would have preferred something more modern like a split image with microprism collar.

Finally, in the bottom right corner is the meter readout, which is nothing more than a moving needle and a permanent circle. With the meter on, the needle moves with available light and proper exposure is made when the needle goes through the circle. If it’s above the circle, you’ll overexpose your images, below and you’ll underexpose.

Beyond that, the only thing to see in the viewfinder images above is some deterioration of some foam around the pentaprism. This type of problem is sometimes called desilvering, but is the result of foam padding that was originally used inside of the camera to protect the prism, has eaten away at part of the reflective coating of the prism. This type of damage is not fixable, and is not unique to the Pellix as many other SLRs can have it, but for some reason, seems to be very common in Pellixes. I have personally handled about ten or so Pellixes over the years, and every single one of them had an issue with the prism.

The Canon Pellix is a solid camera, built to the same standards as other Canon SLRs of the era and supports the same system of excellent FL and FD mount lenses. I probably could have made this review a lot shorter by simply saying the Canon Pellix is just like every other mechanical SLR from the 1960s except it doesn’t have a moving mirror, and I wouldn’t be wrong. Of course there’s always more to using a camera than such a simplification, but what is it like using the camera?

My Results

The time with this Pellix was brief so my only chance to shoot it was with some Kodak Tmax 100 loaded in. As I have a ton of experience with this film, I was curious to see if the surface of the pellicle mirror would have a noticeable effect on the sharpness or contrast of the images the camera would make.

Looking past the obvious light leaks which is a result of this being a loaned cameras that I didn’t want to start working on, the images from the Canon Pellix are about what you’d expect from a 1960s mechanical Canon SLR…and that’s not a bad thing.

True to their reputation, the Canon FLP 38mm f/2.8 lens is optically excellent, but what surprises me is that in order for these images to look good, the light from the lens must pass through the pellicle mirror to the film plane, meaning that any debris, scratches, or other verdigris would negatively impact the image quality, much like shooting through a dirty window might.

The images in the gallery above look sharp corner to corner with no obvious vignetting or other optical anomalies. Staring at the images where the sky was present, I guess I could see a tiny loss of contrast, which could be a result of the mirror, but we’re nitpicking. Any flaws introduced in these images from the mirror are negligible and suggest that when this camera was new, likely would not have bothered anyone.

Although I have never been bothered much by the momentary viewfinder blackout of a moving mirror in a traditional SLR, you don’t realize how much you get used to seeing it until you use a camera that doesn’t do it. With the SLR, everything about the experience feels a little different when you fire the shutter, you hear the shutter, but the viewfinder stays bright throughout the whole process. I don’t know how much that would improve anyone’s photography, but it certainly is neat. I also enjoyed the compact size of the 38mm FLP lens as it made the camera feel lighter than it actually was, or would have been with the standard Canon f/1.2 or f/1.4 lens that was common at the time.

While I enjoyed my time with the Pellix, apart from having no viewfinder blackout and the minor benefit of metal shutter curtains, I can’t honestly come up with a compelling benefit to the Pellix’s design, at least not that the very similar Canon FT QL didn’t also have. Both have the same range of shutter speeds, both support the same lenses (sans the Pellix-only FLP), both have equally good metering systems, both support Canon’s excellent Quick Loading film system, both have support for the optional low-light Canon Booster, and both have very similar ergonomics. Apart from wow factor, the non moving pellicle mirror does not make the sound of the camera firing any quieter. In fact, side by side with a Canon EF (I did not have access to an FT QL at the time of this review), the sounds of the camera were equally loud.

Oddly, the single biggest benefit of other cameras with pellicle mirrors isn’t even available on the Pellix, which is the ability to fire the shutter at a higher frame rate using a motor drive. Canon and Nikon would both employ pellicle mirrors on special purpose cameras for the Olympics, something the Pellix cannot do.

That’s not to say the Pellix is a bad camera. As a model with a one off feature, it adds a bit of variety into Canon’s good but otherwise boring line up of 1960s mechanical SLRs. If I had the chance to own a brand new Canon Pellix or a Canon FT QL, even though the two cameras function and perform almost identically, I probably would still pick the Pellix, just because it’s neat, and I think you would too!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Canon_Pellix

https://global.canon/en/c-museum/product/film63.html

https://funwithcameras.blogspot.com/2022/01/borrowed-canon-pellix-interesting-detour.html

https://flynngraphics.ca/the-collection/the-cameras/f-series/canon-pellix/

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/index-frameset.html?CanonPellix.html~mainFrame

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=1415

Hi Mike:

You write this about the light loss caused by the pellicle mirror:

“In reality, the split is 30/70 to the viewfinder and shutter. With only 70% of the light from the lens reaching the shutter, you effectively lose 2/3 of a stop of light, meaning that with an f/1.4 lens mounted, the same amount of light reaches the shutter as if you had an f/1.8 lens mounted. To the viewfinder, the loss is greater, resulting in an equivalent of having an f/2.2 lens with the f/1.4 mounted.”

I think the second sentence is wrong.

If 70 percent of the light reaches the shutter, then, at the SHUTTER you lose 1/3 of a stop, not 2/3, and if you have a 1.4 lens mounted, the light reaching the shutter is equivalent to a 1.6 lens, not a 1.8. The same error appears in the Aug. 66 Modern Test at page 75 and the Modern preview at page 88. The statement is correct only as to the light loss in the VIEWFINDER.

I think confusions like this contributed to the camera’s lack of success, because “it loses light” is a very easy put down, like recording length in the old Betamax vs Sony debate, and if the AMOUNT of light lost is confusing too, that will make it even harder to sell.

Geert

No, the claim is correct; 2/3 of a stop, approximately, are lost at the film plane. One stop darker means 50% less light received; conversely, one stop brighter means twice as much light received. In reality, the light loss was closer probably to 3/5, but that gets confusing, so to make the marketing message simpler, Canon went with 2/3 of a stop. The Sony SLT cameras, which did exactly the same, have been tested as between 1/2 and 2/3 of a stop noisier than equivalent models without a pellicle mirror.