This is an AGFA Selectaflex, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera, produced by AGFA-Gevaert between the years 1963 and 1967. The Selectaflex was an evolution of the earlier AGFAFlex, and was a premium interchangeable lens SLR featuring a lineup of good to excellent AGFA lenses using the camera’s own bayonet lens mount and supported shutter priority automatic exposure via it’s large coupled selenium exposure meter. The Selectaflex uses a Prontor Reflex-P leaf shutter and a proprietary bayonet lens mount. Including the standard 50mm AGFA Color-Solinar lens, only six lenses were ever made for it.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 AGFA Color-Solinar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: AGFA Selectaflex Bayonet

Focus: 2.6 feet / 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism w/ AE Aperture Display

Shutter: Prontor Reflex-P Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ Shutter Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: PC Port with M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 1074 grams, 868 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/agfa_ansco/agfa_selectraflex.pdf

How these ratings work |

The AGFA Selectaflex was the pinnacle of AGFA’s SLRs, offering a selection of excellent interchangeable lenses, shutter priority automatic exposure, and full manual operation. These cameras are big and heavy and have a few less than ideal ergonomics, but overall are excellent shooters, that for the minor nitpicks I had about the camera’s design, was worth it due to the excellent images it made. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for over the top build quality, great looks, and excellent performance | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

With the soaring success of the Leitz Leica and post war Zeiss-Ikon Contax, the West German camera industry after World War II was heavily rooted in rangefinder cameras. In the 1950s when the rest of the world started to take notice of single lens reflex cameras, with the exception of the Wirgin Edixa, West Germany was lacking options in this segment.

With the soaring success of the Leitz Leica and post war Zeiss-Ikon Contax, the West German camera industry after World War II was heavily rooted in rangefinder cameras. In the 1950s when the rest of the world started to take notice of single lens reflex cameras, with the exception of the Wirgin Edixa, West Germany was lacking options in this segment.

By the time West German SLRs did start to hit the market in the early 1960s, nearly all of them used leaf shutters. AGFA, Kodak AG, Voigtländer, and Zeiss-Ikon all released their own lineup of single lens reflex cameras with Compur or Prontor leaf shutters.

Besides the Wirgin, the only other West German 35mm SLR available in 1960 was the extremely expensive Zeiss-Ikon Contarex. Where were the lower cost alternatives like the Praktica, Pentax, or the Zenit?

I attempted to find an answer to this question by asking several other camera historians that I trust. From Jim Lager, Wes Loder, and Cheyenne Morrison, the most common theme in their responses was that the Germans were stubborn and resisted change.

Some additional factors were that both Leitz and Zeiss were leaders of the industry and both were heavily invested in their rangefinders. Leitz owned the patents on their own focal plane shutter and probably didn’t want to license it to other companies. Although the Zeiss-Ikon Contax had a focal plane shutter too, it was a proprietary design from before the war that would not have worked in an SLR.

For the Contarex, Zeiss created an all new shutter that was overly complex and was not something they wanted to license out to other companies or build themselves in a lower cost model. Leitz would eventually release the Leicaflex SLR in 1964 with a focal plane shutter, but development on this camera was slow as the company wasn’t in a hurry to compete with it’s own rangefinder sales.

In regards to why so many eventual West German SLRs had leaf shutters, a contributing factor likely was that Zeiss owned a controlling interest in both Deckel and Gauthier who produced the Compur and Prontor shutters and it was simply more cost effective to use them, rather than build an all new focal plane shutter from scratch. Zeiss had been profiting on the sale of all folding and solid bodied leaf shutter cameras and likely didn’t want the money train to end by encouraging further development of new focal plane shutters.

Is there another, more specific reason for why West German optics companies showed so little interest in SLRs? Perhaps, but a combination of the factors above, along with the general opinion of stubbornness likely explains it.

As for AGFA, like most other West German camera makers, they had a long and successful line of Compur and Prontor leaf shutter scale focus and rangefinder cameras. From the original Karats to their highly successful Optima series, I am not aware of any focal plane AGFA cameras produced in the 1950s or earlier, so when it came time to develop the company’s first SLR, they went with a leaf shutter design like almost everyone else.

AGFA’s new SLR made it’s debut in 1960 and was called the Ambiflex and was sold under a confusing number of names and model numbers depending on where it was sold and what features it had. Generally speaking, models sold in the United States were called the AGFAFlex, and those sold elsewhere were called the Ambiflex.

The earliest models had a fixed lens and interchangeable viewfinders. If equipped with a waist level finder, the cameras were called the AGFAFlex I and Colorflex I. When equipped with a pentaprism, they were called the AGFAFlex II and Colorflex II. When equipped with an interchangeable bayonet lens mount and waist level finder, it was called the AGFAFlex III in the US, but the Ambiflex I elsewhere. Versions with an interchangeable lens mount and pentaprism were called the AGFAFlex IV and Ambiflex II.

All four versions of the Ambi/AGFA/Colorflex series came standard with a 50mm f/2.8 Color-Solinar lens, but one final model came equipped with a faster 55mm f/2 Color-Solagon lens and was called the AGFAFlex V in the US and Ambiflex III elsewhere.

Beyond the lens, mount, and viewfinder, all models in the series used a body that strongly resembled their Optima rangefinder and likely was chosen to keep a similar look among the company’s family of cameras. All models had a coupled selenium exposure meter with top plate match needle, but no automatic operation. The cameras were made entirely of brass and were very heavy, with top models weighing more than 1000 grams when mounted with a lens.

The Ambiflex series appears to have been produced until the mid 1960s, but I was unable to find a conclusive end date to the series. Although very nicely built cameras with excellent lenses, were technologically behind the times by the early 1960s a huge number of “electric eye” cameras with automatic exposure were hitting the market, so not wanting to be left behind, in 1963, AGFA would release an auto exposure SLR called the Selectaflex.

The Selectaflex is not considered to be part of the Ambiflex series, but does share a number of similar design characteristics to where someone not familiar with the cameras at a quick glance might confuse them with each other. The Selectaflex still used a Prontor leaf shutter with a top 1/300 speed and a modified version of the Ambiflex’s interchangeable lens mount. Physically, the mounts are the same, except Selctaflex lenses have an additional linkage which was necessary for the automatic exposure feature to work. As a result, it is possible to mount Selectaflex lenses on an Ambiflex, but not vice versa.

The image to the right is courtesy of CJ’s Classic Cameras and shows both the lens flange and body mount of both Selectaflex and Ambiflex cameras. You can see the three claw bayonets look the same, but a curved linkage near the top is different.

Other changes to the camera is the removal of the interchangeable viewfinder. The Selectaflex has only a fixed pentaprism and no option for a waist level finder. I have to imagine this was a result of incorporating the read out for the auto exposure system necessitated a fixed prism, or perhaps there just wasn’t enough demand for a waist level finder anymore.

Two versions of the Selectaflex were made, called the Selectaflex I and Selectaflex II, but the only difference was the included lens. If the camera came with a 50mm f/2.8 Color-Solinar, it was a Selctaflex I, but if it came with a 55mm f/2 Color-Solagon, it was a Selctaflex II. Throughout the life of the camera, the size of the Selectaflex logo on the front face of the selenium meter changed with some having a much larger logo than others, but this has nothing to do with the two models. It is not true to say that if you have a larger model you have one model as opposed to ones with the smaller logo. Aside from some coming with two different standard lenses and there being two different sizes for the Selectaflex logo, the smaller of which can also be spelled “Selecta-Flex”, there are no other changes to the model.

Where the Ambi/AGFA/Colorflex models seem to have had some success and were distributed in the United States, I found very little info about sales of the Selectaflex. I scoured through every issue I had from the 1963 through 1966 issues of Popular and Modern Photography magazines and found no mention of the camera. Even in Modern’s annual year end wrap-ups of currently available camera models, only the AGFAFlex and Colorflex models showed up, suggesting that perhaps the Selectaflex was a Europe only model. Furthermore, no photo dealer catalogs from that era mention the camera, nor does any of the dealer guides shared in Pacific Rim’s Reference Library.

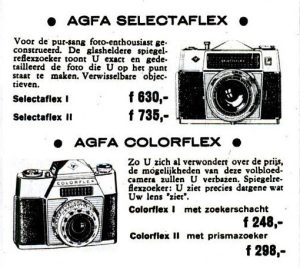

The only material I found for the camera were in German and French language catalogs. The ad to the right was posted in the June 1964 issue of Kampioen magzine which is in Google’s archive. In that article, the prices are listed as f 630 for the Selectaflex I and f 735 for the Selectaflex II, suggesting a 17% premium for the better lens. Even more interesting is that the simpler Colorflex I and II sold for f 248 and f 298 respectively, suggesting an almost 200% increase in price from AGFAs least to most expensive SLRs.

Beyond these short ads, I found no other reference material for the camera, no reviews, no dealer catalogs, or proper full page advertisements. I have to imagine that the very high price, extreme complexity, and relative newness of an auto exposure camera led to very low sales. Another mystery is in how long the camera was produced. Most sites online suggest the camera entered production in 1963, but when it ended ranges from 1966 to 1969. I would guess the 1966 number is more accurate, but even that’s hard to believe as it’s clear the camera was a slow seller, and it wouldn’t have made sense to keep offering such a slow selling model for so long.

Whatever the true dates are that the camera were made, it is very clear that not many were made. As I write this, eBay shows a total of five cameras available for sale worldwide. This is in comparison to over 40 combined sales for the Ambiflex, AGFAFlex, and Colorflex.

After the Selectaflex, AGFA would continue to make cameras, but would mostly exit the SLR business. The company’s Optima and Selectronic lines would continue with mostly rangefinder and scale focus models throughout the 1960s, 70s, and early 80s. In 1980, the company would release three Selectronic SLRs, models 1, 2, and 3. Although featuring the AGFA name and the company’s trademark large orange shutter release, the Selectronic SLRs were built in Japan by Chinon.

Today, cameras like the Selectaflex are collectible for a variety of reasons. Rarity, an interesting design, excellent lenses, and the fact that it’s a German made leaf SLR from the peak of Germany’s reputation as a place where great cameras came from make it appealing. By far, the thing working against it is the poor reputation of leaf shutter SLRs in general as this was a format that was notorious both for being unreliable and that very few people will work on them usually mean that when they are found, they rarely work. Whether you like the camera for it’s design, history, or if you’re extremely lucky enough to find one working, I would say that if given a chance to pick one up, it would give you many compelling reasons to do so.

My Thoughts

I haven’t had the best of luck when it comes to AGFA’s mid century cameras. In my years writing reviews, I’ve come across a huge number of AGFA cameras. My favorites by far, are the folding Karats. I wrote about the Karat way back in November 2015, and that camera remains one of my favorite rangefinder cameras due to it’s excellent viewfinder. In November 2020, I wrote about the AGFA Flexilette, which is a strange 35mm TLR and although that camera did work, the focus ring was so stiff, it was difficult to use. The AGFA Selectronic 3 isn’t technically a mid century camera, but it remains the only AGFA SLR I’ve reviewed, and they didn’t even make it.

What you haven’t seen however, are all the failures of cameras I’ve started to work on, but could never finish. I have a pile of inoperable Colorflex and AGFAFlex SLRs, I have many non-working examples from the Optima series, including the very first model from 1958, an absolutely gorgeous AGFA Selectronic S that looks mint, but has serious film transport issues, and an equally nice AGFA Optima Flash with a lens so hazed up, it looks like I’m shooting through a steamed up shower door. So when I had a chance to check out this nice looking AGFA Selectaflex, I didn’t hold my breath.

To my surprise, when the Selectaflex showed up at my doorstep, it was not only in great physical condition, but everything seemed to work. The meter did respond to light, but didn’t seem accurate, but more importantly, the shutter and film transport worked, the lens was clear, and everything else appeared to be in good working order.

In the limited number of reviews out there mentioning this camera, one thing that is mentioned in every single one of them is how heavy this camera is. Now, I’ve handled a good share of heavy SLRs, and at 1074 grams with the f/2.8 Color-Solinar lens mounted, it definitely has some heft, but it’s not to the level of the KMZ Start at 1300 grams or even the original Leicaflex at 1144 grams. Compared to those two cameras however, the AGFA is a bit smaller, both in width and depth. The Leicaflex and Start are both heavy and massive, whereas the Selectaflex is a bit more condensed, which I think gives the illusion of a heavier camera. Whatever the case, this is still an impressively large piece of brass and glass that I wouldn’t want to drop on my bare foot!

As is typical of most AGFA cameras, the top plate of the Selectaflex is pretty bare, with the rewind knob with fold out handle and flash sync port on the left…

…and the cable threaded shutter release and ASA/DIN film speed selector on the right. A knurled ring around the shutter release is confusingly used for the self-timer. In order to use it, you must select a “V” position using a small switch on the left side of the mirror box, then while pressing down on the shutter release, you must also twist it in the direction of the arrow for it to work. As is normal practice, I never use mechanical self-timers on old cameras, so I never tested this to see how it worked.

There’s little else to see other than the pentaprism hump, which unlike the previous Ambi/AGFA/Colorflex SLRs is not removable. In my opinion, this isn’t much of a loss as even when I use a pro level SLR with this feature, I rarely use it. I find that waist level photography is most effective using cameras designed for it, whereas mid level cameras like this that are designed to do both usually have some sort of compromise. If the necessity for the auto exposure feature meant that the prism needed to be fixed, I think that was a good decision.

Flip the camera over and the base plate has a nice piece of body covering the break up what little there is to see. A 1/4″ tripod socket is off to one side, which on a camera with a substantial weight like this is unfortunate. On the other side is a recessed rewind release button, and on each side are two small screws that are flush mounted to the body covering, so they do not offer any protection like feet would.

Around back is the rectangular opening for the viewfinder, the film advance handle, and beneath the film door, the subtractive exposure counter which shows the number of exposures remaining on a roll of film. Unlike other cameras with subtractive counters like the Kodak Retina, the shutter release does not lock when the counter reaches ‘1’. Resetting the exposure counter must be manually done by turning it with your finger to whatever number of exposures are on each new film cassette loaded into the camera. To the left of the eyepiece is some sort of adjustment port which serves no purpose to the photographer.

The camera’s right side has the sliding latch for the film door. On the front corner of the body covering on each corner of the camera are two strap lugs which are specially designed for this camera. With the correct strap, the Selectaflex can comfortably hang from a neck strap, but without it today, you’re not likely to find something that will work with it. Also note on this side of the mirror box is a switch for setting X flash synchronization or V for the self-timer.

The left hinged film door reveals an otherwise ordinary film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a multi slotted and fixed take up spool. Visible through the film gate is the back of the Prontor Reflex-P shutter which lacks an instant return mirror. In the image to the right, the shutter is not cocked, which means the shutter is closed and the mirror is in the up position, meaning that the viewfinder is dark. You’d need to wind the film advance lever to raise the mirror and open the shutter, and to avoid exposing the film with the shutter open, a capping plate drops down protecting the film gate from light.

The inside of the film door has a metal roller and two posts which helps stabilize the film cassette and maintain pressure on the film as it travels over the sprockets. The pressure plate is large and covered with dimples which also helps to reduce friction as film passes over it. Yarn light seals exist in the door channels and a strip of fabric near the door hinge are there to prevent light leaks and on this camera were still in good shape, not needing replacement.

Looking down upon the top of the lens and shutter, we see the shutter speed ring closes to the body of the camera. Speeds from 1/300 down to 1 second plus Bulb are changed by rotating a metal ring with “ears” near the sides of the shutter. The inclusion of these ears make gripping the ring much easier.

Next is a small rectangular window which shows manually selected f/stops from f/22 down to f/2. With the f/2.8 Color-Solinar lens mounted, you cannot open it up all the way to f/2, but you can with the lens removed, or with the f/2 Solagon lens mounted. Beyond the setting for f/22 is a white on red letter “A” which is to be used in shutter priority auto exposure mode. With this ring in the “A” position, the camera will pick an appropriate f/stop for the shutter speed you’ve selected and amount of light.

Note: The Auto Exposure system on the Selectaflex only works with shutter speeds from 1/30 to 1/300. When manually selecting a shutter speed of 1/15 or slower, a red flag will be visible in the viewfinder indicating the AE system is deactivated. Furthermore, if proper exposure is not possible using a speed between 1/30 and 1/300, the red flag will also be present. Any time the red flag is present with the shutter in “A” mode, the shutter release is locked.

The Selectaflex uses it’s own bayonet lens mount which is not used by any other camera. In the History section above, I mention that the three claw bayonet is the same as the one used on the earlier AGFA Ambiflex series, but internal linkages needed for the AE feature on the Selectaflex mean that the Selectaflex cannot use the earlier lenses. It is possible however, to mount a Selectaflex lens onto an earlier Ambiflex series body.

A small black tab near the 3 o’clock position around the shutter releases the lens. Press this tab towards the body while rotating the lens counterclockwise and it will come off. Reinstalling is the opposite. I did notice on my example, it took an extra mount of effort after reinstalling the lens to make the release tab click into place. Without doing this, the lens can easily fall off, so be careful. The only other things to see on the front of the camera is the large rectangular window for the selenium meter, and a small window to the right of the meter for letting light in to see the meter readout within the viewfinder.

The Selectaflex viewfinder can best be described as simple, yet effective. Featuring a reasonably bright focus screen that shows even brightness with only a small amount of vignetting in the corners, it should be usable in all but the darkest shooting conditions. Unlike other leaf shutter SLRs of the era like some versions of the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex in which only the center of the image can be used for precise focus, the entire Selectaflex viewfinder can be used for both focus and composition.

In the center is a large split image focus aide. There is no microprism circle, but between the two, I prefer the split image like this. Unlike later SLRs of the 70s and 80s which reduce the size of the split image, the one here is about the same size as both the split image and microprism would be combined on a later Nikon SLR like the FM.

Finally, off to the right is the meter readout of f/stops and the red flag which is used to determine if the camera’s auto exposure system can make a properly exposed image. According to the manual, even with the camera in manual mode, the meter will still make recommendations for aperture which you can choose to ignore or not. Sadly, the selenium meter on this example was no longer working, so the meter readout was always in the red, showing the smallest possible f/stop, no matter what light I pointed it at. Thankfully, the Selectaflex doesn’t require it’s AE system to work, and can be used entirely manually, which is how I intended to use it.

Overall, the viewfinder on the Selectaflex is very good for it’s era. At a time where many Japanese SLRs still offered only a ground glass circle, and many German SLRs had viewfinder screens that could only be focused in the center, the one found here has the best of both worlds. I would have liked some kind of shutter speed readout, which would have been useful while shooting the camera manually, but that’s only a minor omission from an otherwise fantastic camera.

AGFA may have been a film first company that wasn’t a leader in the SLR market, and the Selectaflex might not have been exported to the United States, but nevertheless, this is a well designed and easy to use camera that also looks great and has an awesome lens. I wish I had access to more than just the standard Color-Solinar, but apart from buying another camera with a different lens attached, finding the auxiliary lenses for these is extremely difficult because very few were made. Complicating it further, very few people know what they are just by looking at the mount so I am sure that many times when these lenses have come up for sale, they were likely mislabeled, making searching for them very difficult.

The more I handled the camera, the more excited I was to shoot it. It’s look, heft, and handling were better than other AGFA SLRs I have come across, and with this one appearing to be in good working order, I was eager to put some film into it. Keep reading to learn how those rolls turned out…

My Results

Satisfied that the Selectaflex was in good enough operational condition to potentially break my mid century AGFA curse, I loaded it up with a roll of bulk Kodak TMax 100 on a late winter day to shoot some old cars in a parking lot I often pass on my way home from work. I know TMax 100 to be a fine grained film that if the camera worked properly, would show off the sharpness of the Color-Solinar lens. After the first roll, I took the camera out again in the summer of 2022 with a roll of fresh Fuji 200 for some color shots.

When I am writing reviews for this site, I jump around between drafts of upcoming reviews. I will sometimes do the same sections of multiple reviews at the same time as I develop or scan in mulitple batches of film. When I was working on the one for the AGFA Selectaflex, I happened to also be writing my review for the Zeiss-Ikon Contax I, and in that review, I comment at how great the images I got from it’s 4-element f/2.8 Tessar lens saying that you don’t always need a higher spec lens to get great images, and I feel like I am repeating myself here, even though you will see these reviews weeks apart.

So even though it feels like I just said it, I’ll say it again that you don’t always need 6+ elements on a ~50mm prime lens to get great images as evidenced by the 4-element Color-Solinar on the Selectaflex. Images in the gallery above are extremely sharp in the center with only the slightest hint of softness in the corners. Vignetting was not visible even in scenes where the sky was present, the black and white images showed excellent contrast, and the color images showed great color accuracy. Although I do not have access to one, knowing that this camera also came with a 6-element f/2 Color-Solagon, I feel as though differentiating between images shot with either lens would be very difficult. If I ever do come across a Solagon and can shoot it, I will be sure to update this review.

The camera performed admirably through both films, but unfortunately, the idiot that was using it opened the back of the camera with the color roll of film still loaded in it, completely ruining a third of the roll and adding light leaks to a few other shots. The two of the yellow flowers show the leaks, which are entirely my fault and not of the camera’s.

I was not able to test the auto exposure system as the meter wasn’t responding to light, but that the camera offered full manual control was a huge plus. I do not know that even if the metering system was working, that I likely would have depended on it as I’m more of a “Sunny 16” guy, but having that feature available in the early 1960s on a high quality German SLR would have been a nice to thing to have.

Using the Selectaflex wasn’t quite as nice as the images as I found the tall top plate and even taller shutter release to be a bit of a stretch for my average sized hands. It didn’t reach a level I would call uncomfortable, but I think someone with smaller hands would have struggled. Many of AGFA’s earlier cameras in the Optima series had front body shutter releases, which is something I think would have benefitted the Selectaflex.

The Color-Solinar’s focus ring is nearest the front of the lens and is easy enough to locate, although the thin metal grip ring was a little tight, certainly something that could be remedied by a CLA. As is the case with most leaf shutter SLRs, the shutter speed and aperture rings are squished together nearest the body of the camera. The Selectaflex isn’t any better or worse than other similar cameras, but if you’re used to the control layouts of Japanese focal plane shutter cameras, it can take a bit of getting used to. Any time I wanted to change exposure settings, I could never do it reliably with the camera to my eye. Lowering the camera to your chest to look down upon the two rings is a must. Again, not a deal breaker, but not as nice as other designs.

I did enjoy the viewfinder though. Unlike other leaf shutter SLRs like the Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex Super, the entire viewing screen can be used for focus. The inclusion of a large split image focus aide is very welcome, unlike many Japanese SLRs from the 1960s. Also, being able to view the meter’s detected aperture (even though it didn’t work on this one) within the viewfinder is a nice feature as well.

Overall, I enjoyed shooting the Selectaflex. It was different enough from just another 1960s SLR to be fun and interesting, without being so quirky as to frustrate me while shooting. The few ergonomic misses that the camera had were not enough to ruin my enjoyment of the camera, and any mild complaints I did have, were immediately put to rest when I saw the high quality images the camera made.

It’s tough to give a fair judgement of a camera like this. On one hand, it is an impressive hulking piece of metal that exudes style and quality, yet it came out at a time when it’s feature set was a bit dated, compared to it’s competition. I suspect that many who bought the Selectaflex would not have considered anything made in Japan at the time, or maybe didn’t even have an option to do so, and for those, they likely were very happy with this camera. If however, there was a 1960s version of Amazon where one could order a camera from anywhere in the world, I would guess that most people would have purchased something different.

Therein lies the best feature of the Selectaflex, it’s different. It’s easy enough to shoot, makes great images, looks awesome on a shelf, and not many people have one. It is for those reasons I would have no problem recommending a good working example to anyone considering picking one up.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Selectaflex

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/non-karat.html#selectaflex

https://www.flickr.com/photos/dutchdennis/6172020352

http://photographytoday.net/forums/viewtopic.php?f=8&t=1479

http://forum.mflenses.com/agfa-selectaflex-t45584.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/agfa-selectaflex.5507991/

https://www.kamera-museum-scholz.de/agfa-kamera/spiegelreflexkamera/selectaflex/ (in German)

http://www.tugboatlars.se/AgfaSelectaFlex.htm (in Swedish)

Congratulations (on a working Agfa SLR) Worth the wait. I’d put this towards the top of my ‘user’ list

I enyoyed your review of the Selectaflex – I’ve never seen one. I do have an Agfaflex IV, which I had overhauled by Chris Sherlock, and I enjoy using that.

Thanks for the compliment! Glad to hear you got one serviced by Chris, especially since he’s not doing it anymore. I’d gladly take your serviced Agfaflex IV over my Selectaflex! 🙂