This is a Miranda A, a 35mm single lens reflex camera made by the Miranda Camera Company in Japan starting in 1958. The Miranda A was the first Miranda camera to have a film advance lever, instead of a knob, but still shared many characteristics of their earlier models such as a shutter speed dial with two rings for fast and slow speeds, no internal support for an automatic diaphragm, and the company’s earlier logo. All Mirandas of this era came standard with chrome bodied Soligor lenses that produced high quality and sharp images. The Miranda A has a much better build quality than later cameras, and can often still be found in good working condition, making this an excellent example of a 1950s Japanese SLR.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.9 Soligor Miranda coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Miranda Bayonet and 44mm Screw Mount

Focus: 18 inches to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism, 96% Field of View

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/30 X-Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 937 grams, 649 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/miranda_pdf/miranda.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Miranda A is the first of the second generation Mirandas with a new body, lever wind, and is often found with externally coupled Soligor lenses that have excellent optics. Unlike later models with questionable build quality, the earlier models are just as nice as anything out there, and when found in good shape, are excellent shooters. They lack many of the modern features from SLRs of the next couple of decades, but it’s that old school charm, combined with great looks and an excellent lens that make them very appealing. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.4 | ||||||

History

The Miranda Camera Corporation was founded in 1946 as Orion Seiki Sangyō Y.K. In English, this translates to Orion Precision Products Industries Co., Ltd. Orion didn’t start out making cameras directly, rather their first products were camera related items such as couplers which allowed Contax/Nikon lenses to be used on Leica screw mount cameras. They also released a number of other camera related products such as bellows and Mirax reflex housings.

Orion’s first attempt at making it’s own camera was the Phoenix SLR prototype from 1954. This prototype was developed over the period of several years and was only shown to the press as a promotional product designed to gain funding for future camera products.

By 1955, Orion was ready to release a production version of the Phoenix, but due to a trademark dispute they had to come up with a different name. They decided to call their new SLR camera the Orion Miranda T. The Miranda T is notable as being the first Japanese SLR with a pentaprism finder. The first SLR with a pentaprism was the Italian built Rectaflex. Prior to this, all SLR cameras had a waist level viewfinder in which the photographer would flip open a lid on top of the camera and peer down into the body to compose their image.

In an effort to avoid confusion between Orion’s previous camera related products and their new Miranda T SLR, the company completely renamed itself Miranda Camera K.K. in 1957, a name which they kept throughout the remainder of the company’s existence.

In the late 1950s Miranda formed a very strong relationship with an American import company called Allied Impex Corporation (AIC). For a reason that I was never able to discover online, in the summer of 1959 Miranda stopped all Japanese domestic sales and all sales were export only to Europe and the United States. Miranda returned to the Japanese market in the fall of 1964 but continued to be heavily influenced by AIC, eventually being acquired by AIC by the end of the decade.

While researching my review for the Miranda D back in 2016, I discovered an interesting letter on an archived Geocities website called “Bill’s Miranda Camera Page”. The letter is from a man named Lee Mannheimer who worked for AIC from 1969 – 1976. In the letter, Mr. Mannheimer recalls his time there and offers his version of the history which partially explains why the company failed.

The letter was likely written in the late 1990s or early 2000s, and Mr. Mannheimer acknowledges that his memory was a bit fuzzy, but he goes on to explain his version of the company’s history while he worked there.

At one point in the letter, he says:

WHEN THE COMPANY WENT PUBLIC THEY (AIC) HAD THE MONEY TO ACQUIRE THE OWNERSHIP OF THE MIRANDA CAMERA FACTORY IN JAPAN. SHORTLY THEREAFTER THE JAPANESE GOVERNMENT PASSED A LAW OUTLAWING ALL FOREIGN OWNERSHIP OF JAPANESE COMPANIES. RALPH (Ralph Lowenstein, a German Jew who was one of the founders of AIC) MOVED TO JAPAN TO MANAGE THE FACTORY. THIS WAS THE BEGINNING OF THE END FOR MIRANDA AS RALPH DID NOT UNDERSTAND THE JAPANESE CULTURE AND BROUGHT WITH HIM THE GERMAN ATTITUDE THAT HE WAS THE BOSS AND THEY WERE THE WORKERS.

In Mr. Mannheimer’s letter, he doesn’t go over specific dates of when these things happened as they all seemed to occur prior to him working there in 1969. Some other websites state that AIC didn’t officially take over Miranda until later in the 1960s which would not explain why they stopped selling cameras in Japan around 1959. But his comment above about AIC buying the rights to Miranda, and that Japanese law forbade foreign ownership of Japanese companies, perhaps explains why Miranda cameras were built for export only and not sold domestically. Perhaps there was some loophole in the law that said that a foreign company could own a Japanese company, but it’s products could not be sold there.

He then goes on to say that one of AIC’s owners, Ralph Lowenstein, moved to Japan to run the company which could possibly explain how Miranda would have once again begun to sell it’s products in Japan.

Of course, this explanation could just be me reading between lines and interpreting a story that’s not even true. In either case, it is unlikely anyone will ever come up with a better explanation as the history of the entire Miranda camera is quite scarce already.

After the release of the first model, Miranda cameras would receive incremental updates with regularity, sometimes receiving new model designations, but on occasion there would be mid cycle updates that did not receive a new name. The first few knob wind models would be differentiated by different cosmetics, different standard lenses, and eventually a redesigned shutter with a top 1/1000 speed.

In 1958, the Miranda would receive it’s first major update, in what seemed to be a new line of “alphabet” cameras that had a new body, a new film advance lever with integrated exposure counter, and a new series of lenses. The Miranda A would be followed up with models B, C, D, F, and G (strangely there was no Miranda E).

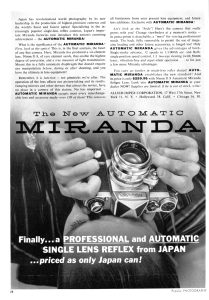

In the advertisement to the left from July 1958, the Miranda A (then referred to as the Automatic Miranda) sold with the 6-element Soligor 50mm f/1.9 lens for $259.95 which when adjusted for inflation, compares to just under $2500 today, making it quite the investment for what was not only a relatively new camera brand, but also that in 1958, the SLR design was still not the preferred choice for pros.

Later models in the alphabet series were the Miranda B which added an instant return mirror, the Miranda C which revised the prism and changed the standard lens, and the Miranda D which came in a new body, but also lost the top 1/1000 shutter speed.

Despite having what was a pretty competitive feature set, Miranda never competed directly with top of the line Japanese or German cameras like Canon, Nikon, or Leica. Instead, they offered competitively featured models at prices a bit lower than other brands.

Further differentiating themselves from their competition is their frequent use of scantily clad women in their advertisements. Readers of magazines like Popular and Modern Photography in the 1950s and 60s likely remember many of the company’s advertisements with photos shot by photographer Hal Reiff. His Miranda articles was the focus of an article I previously wrote a couple of years back with some behind the scenes info about how the photos were shot and who was in them.

Interestingly, in early 2021, I was contacted by a woman from New York named Maureen who told me that the women identified as “Nancy” was her aunt and was still alive, living in New Jersey. Nancy was her aunt’s real name and although she said her aunt spoke fondly of those days as a model taking those pics, it wasn’t something she was interested in speaking to me about.

Miranda would remain profitable through most of the 1960s. Their reputation as an innovative company with features only available on more expensive cameras made them appealing to advanced amateur photographers. After 1967 however, their quality control started to suffer which caused their reputation to nose dive. The company would limp into the 1970s and would struggle to compete with their competitors who were releasing smaller, and more intelligent cameras capable of auto exposure and had other advanced features. By 1975, the company would be completely bankrupt.

After Miranda went bankrupt, the “Miranda” name was reused in the late 80s by a completely unrelated company who made a cheap line of point and shoot cameras. Another model called the Miranda MS-1 was sold in the UK by the Dixon’s department store. It was made by Cosina in Japan and was a rebadged Cosina CT-1 and used the Pentax K-mount. It’s also worth mentioning that there was also an unrelated Japanese company also called Orion Seiki who made a line of folding cameras in the 1950s that predates the Orion/Miranda company. The presence of this company could have also contributed to why the Orion Camera Company changed it’s name to Miranda but I never found any conclusive evidence during my research.

Today, Miranda SLRs have a questionable reputation. For those who remember them when they were new, the later models were unreliable and had a poor reputation. Adding on decades of dust, grime, and disuse hasn’t helped things either as many Miranda cameras are found non working today.

If you are patient though, and are willing to go back to the earlier models like the Miranda A, you’ll find the build quality to be much better, and with the excellent optics provided by the Soligor lenses, can still be very good shooters today. The early Mirandas are very attractive cameras with a pretty advanced feature set, and under the right circumstances, can make an excellent addition to any collection.

My Thoughts

It has been a while since I’ve done a Miranda review. Back when I first started this site, I became attracted to the design and relative obscurity of this Japanese brand, buying several Miranda cameras, all of which had problem after problem. In my 2016 review for the Miranda D, I recanted what I called the “Miranda Curse” in which no matter what I did, there always seemed to be a problem that ruined all of, or significant parts of rolls.

In that review, I thought I had discovered the secret to shooting Miranda’s with a minimum of challenges, which was that the older the model, the more likely it was to work. It made sense, as Miranda suffered through some distribution problems and a lack of brand awareness throughout the 1960s, it was only a matter of time before quality control began to suffer. So having had luck shooting an older Miranda D, I wondered how an even older model would fare. It would take a couple of years, but I would finally get my answer when I picked up a really nice looking Miranda A at a camera show for the princely sum of only $25.

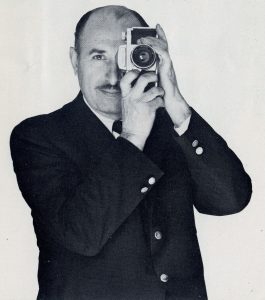

The Miranda A dates back to 1958, making it the oldest Miranda in my collection and shows excellent build quality. Although this model has taken a couple dings in it’s past, it is still in wonderful condition. The chrome plating is very well applied and still feels smooth to the touch. As you might expect from any 1950s SLR, the camera is heavy, especially with the automatic f/1.9 Soligor lens attached. At 937 grams, it is similar in weight to a Nikon F with the standard prism and f/2 lens. Also, like other Mirandas of the era, it also has the original stylized Miranda logo, which I prefer over the company’s later version.

From the first Orion SLR from 1955, the top plates of early Miranda SLRs varied quite a bit from model to model. With the release of the Miranda A in 1958, a more consistent design began to appear. The Miranda A was the first model with a lever wind, which for the time would have been a very nice addition.

On the left is the combined rewind knob with fold out crank, and a film reminder dial beneath it. The Miranda A has no meter, but the design of this reminder in which you can both set speeds from ASA 5 to 1000 plus film type using a separate inner ring, was nicely done.

Above and to the right is the prism release button. A notable feature of almost every Miranda camera was it’s interchangeable viewfinders, which would become a standard feature on professional level SLRs. With the prism removed, the camera could be used at waist level, allowing for lower and higher angle compositions. Optional hoods and precision viewfinders were also available, further adding to the flexibility of the system.

Removing the prism is easy, simply slide the release in the direction of the rewind knob, and slide the entire viewfinder towards the back of the camera along a track. I find this method superior to other cameras with a similar feature like the Exakta and Nikon F, in which the viewfinder lifts up as there’s almost no chance the viewfinder could slip out and fall to the floor.

To the right of the viewfinder is the shutter speed dial which uses a two step design. The top section is painted black and has speeds from 1/30 to 1/1000 plus B and and X. The user manual does not specify what the X-sync speed is, but it’s location halfway between 30 and 60 suggests it’s probably 1/40. In the center of the fast speed dial is a chrome shaft with a red arrow on it. This red arrow is what’s used to select the fast speeds. Selecting a speed can be done with or without the shutter cocked. With the shutter uncocked, the arrow points up and to the left, and with it cocked, it points down and to the left.

Around the perimeter of the black shutter speed dial are two chrome “ears” that are used to set the slow speeds from 1 to 1/15 second. Unlike most other cameras which have a separate ring for slow speeds, there is no point on the high speed dial that must be set to activate the slow speeds. Choosing any slow speed overrides the fast speeds, regardless of the position of the black dial.

Warning: This is critically important, as an accidental bump of the slow speed dial will enable the slow speed governor, potentially giving you a drastically slower speed than you had expected. It is very important to make sure the black arrow on the slow speed ear points to a red arrow on the top plate which is the position where no slow speed is selected.

Warning 2: Since I’m sounding the alarm, another thing to be aware of, is that like many SLR and rangefinder cameras from this era, the entire shutter speed dial spins as the shutter fires, so you must take care not to have it come in contact with anything while firing the shutter, as even the slightest amount of drag on this dial will cause the shutter to not fire correctly.

To the right of the shutter speed dial is the combined film advance lever and exposure counter. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made, and must always be manually reset after loading in a new roll of film.

The bottom of the camera is much less exciting, featuring only a rewind release button and centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket. The location of the tripod socket in the center of the camera’s mass means it will have balance when mounted on a tripod. This is especially useful for SLRs which can have heavier lenses mounted. Also notice a small metal foot exists below the mirror box, to help the camera sit level on a flat surface without falling forward.

Around back, there’s nothing to see other than an engraved “Miranda A” and the camera’s serial number. The rear eyepiece for the viewfinder is internally threaded to accept some viewfinder accessories like a right angle viewer, rubber cup and some others.

The Miranda A is a full bodied and heavy camera, and with the all chrome Soligor f/1.9 lens mounted, is quite a bit chunky. From the side, you get a real sense of the camera’s dimensions as the tallish top place and pronounced edges of the lens give it an intimidating profile. On the camera’s left side is a sliding latch for the film compartment and on both sides of the camera, are front angled strap lugs.

The right hinged film compartment is surprisingly modern considering the age of this camera. Film transports from left to right onto a dual slotted and fixed take up spool. Film winds on the spool clockwise, which is the opposite of how it is in the cassette, which people claim helps lay the film flatter as it transports through the camera. The film pressure plate is standard size, but has divots all over it, helping to reduce friction on the film. Lastly, a small chrome spring puts tension on the cassette, preventing it from wiggling around inside of the film compartment.

One final feature that’s not readily apparent until you accidentally discover it, is that the door is removable. Unlike most other 35mm SLRs with removable doors that have a little latch on the hinge to release it, on the Miranda, you simply lift up on the door with it open and it slips off two pins holding it into place. I mention about discovering this accidentally, which is how I did it, because if the door moves up even a small mount, it won’t close properly, so if you ever have trouble trying to close the door on a Miranda A, make sure it is properly seated.

Throughout the roughly twenty years that Miranda SLRs were produced, they had one of the coolest lens mounts, a dual screw and bayonet lens mount. The Miranda’s external four lug bayonet allowed for quick and easy changes of lenses, like pretty much every other camera with a bayonet lens mount, but internally, there was a 44mm screw mount which was designed to be used with a series of professional accessories like lens tubes and Focabell bellows attachments, but also a series of lens adapters for all of the popular camera systems of the day.

The designers of the Miranda were aware that it might be a struggle to market an all new Japanese SLR to photographers who might have already had their own system of lenses. In 1955 when the first Orion made it’s debut, many western photographers were still apprehensive about Japanese cameras, and combined with having to invest in new lenses might have kept people away, so the Miranda mount was designed with a short enough flange distance and large enough throat to support Exakta and M42 (then called the Praktica mount) adapters. A later adapter for the Nikon F mount was also made available. In addition to SLR adapters, Miranda also had adapters for Leica Thread Mount and Contax/Nikon lenses as well, meaning that Leica owners could sample the world of SLRs while using their existing lenses.

Another forward thinking feature of the Miranda is that all early Miranda cameras had a front shutter release button, which only helps for stabilization of the camera while pressing the shutter release, but also allows for the use of lenses with fully and semi-automatic diaphragms without any coupling into the camera.

Lenses like the Soligor Miranda 50mm f/1.9 had an external shutter release, that when mounted to the camera, covers up the body’s shutter release. When you press the shutter release on the lens, the lens automatically stops down to your chosen f/stop before pressing the actual shutter release on the body. While not quite as elegant as internal couplings that would become common in the next decade, this was how it was done back then. Ihagee Exaktas with externally coupled lenses worked the same way, except unlike the Exakta whose shutter release was used by the photographer’s left hand, the Miranda was right handed.

The Soligor lens mounted on this example has a fully automatic diaphragm, which means it stops down with pressure on the shutter release and automatically re-opens after. This is different from semi-automatic lenses like those from Carl Zeiss, Asahi Optical, and Yashica which had a spring loaded lever on the lens which must be pressed to open the lens before each shot to achieve open aperture composition.

One modern feature the Miranda A lacks is an instant return mirror, which means the viewfinder blacks out after each time the shutter is fired. It will not lower until you wind on the camera. The first Miranda with an instant return mirror was the Model B, released a year later. Assuming you didn’t need to take shots in quick succession, this wouldn’t have been a problem.

The viewfinder itself is as simple as it gets. No information about exposure or shutter speeds is present, nor is there any focus aides like a split image or microprism circle. A large ground glass rectangle is all you see whether you use the pentaprism or waist level finder. Miranda did not make different focusing screens for this model, but later versions of the camera added focus aides, so it may be possible to swap them, I’ve never tried it. The lack of any Fresnel pattern results in corners that show heavy vignetting. This isn’t a huge problem outdoors, but does make composing your image indoors more difficult.

Still, without the focus aides, the viewfinder is reasonably bright, at least good enough where all outdoor photography should be easy to see. In heavy shade or indoors, things can get quite dark, especially in the corners, but still not as bad as some early SLR and TLR viewfinders I’ve used.

The Miranda A is a perfect mix of old and new. None of the camera’s controls are strange enough to be unfamiliar to anyone whose never shot one before, but the presence of “old school” features like a non-instant return mirror, external lens coupling, and separate controls for fast and slow shutter speeds make shooting the camera more interesting than “just another SLR”. I have been enamored with the history and looks of Miranda cameras ever since I started collecting them, and of the models in my collection, the Miranda A might just be my favorite, especially with the gorgeous all chrome Soligor 50mm f/1.9 lens attached.

Of course, a camera can be as interesting or as boring as you like, but it’s not worth much if it can’t make good images, so how does the Miranda A perform there?

My Results

I had originally slated the Miranda A for a couple rolls last winter, but things got in the way and I never shot anything in it, so this this summer I prioritized shooting the camera. It came to the top of the queue shortly after receiving a 100′ bulk roll of EFKE KB25 from my friend Paul Rybolt, who got it from our mutual friend Dan Arnold who passed away late last year. So, in a way, this roll through the Miranda was my homage to Dan, shooting his film that made a pit stop in Yellow Springs, Ohio on it’s way to me.

The images in the gallery above are about as good as any I’ve seen from any other mid century Japanese SLR. In their early years, Miranda was a maker of fine cameras, and Soligor makers of even finer lenses.

Looking through the entire roll of images, not a single one was out of focus or had uneven exposure. Sharpness is excellent across the frame with no noticeable vignetting or optical degradation near the corners. I am not normally a bokeh person, nor do I usually take too many close focus narrow depth of field shots, but in the ones in the gallery above, I found the out of focus details nice and creamy, lacking in any distracting types of “soap bubble” bokeh that some people like.

Overall, the images from this camera and lens combination were excellent. Despite my well documented bad luck shooting Mirandas, I have always held the opinion that the company started out as a quality camera maker and that the older cameras hold up better than the later ones do. The Miranda A from 1958 is not only the oldest Miranda in my collection and the oldest I’ve ever shot, but is one of two that went through an entire roll without giving me a problem, the other being the Miranda D from 1960.

There is a lot to like about the Miranda in addition to it’s good looks and excellent lenses. The Miranda A has excellent feel, weight and balance, no different from other quality SLRs from 1958. It is made entirely of metal covered in shiny chrome and a synthetic body covering, both of which have stood the test of time. It feels pretty similar in size and weight to a Nikon F with the standard prism. I generally prefer SLRs with front shutter releases like the Miranda as the action of pressing the shutter release is towards your face, helping to stabilize the camera in ways pressing down on a top shutter release can’t. The lack of metering was not an issue at all with this camera as I didn’t feel like it was lacking without it.

The only major flaw with this camera is in how the slow speed dial works. On most cameras with a separate slow speed dial, you need to set the fast speed dial to it’s slowest setting, usually marked “1-25” or “1-30” to engage the slow speeds. On the Miranda A, selecting any of the speeds on the slow speed dial will override the fast speeds, making it very easy to accidentally select a slow speed unintentionally. To avoid this, you must make sure both the triangles on the fast and slow speed dials are always pointed toward another. This is a very poor design, especially with how easily it is to accidentally turn the slow speed dial away from the triangle.

My only other complaint about the camera falls into the nitpick category, which is that I would have preferred a brighter viewfinder with some type of focus aide. While I prefer split image focus aides, even a microprism circle is better than nothing. The Miranda’s viewfinder is just a flat piece of ground glass with nothing else.

There’s not much I can really say about the Miranda A that I haven’t said already in this article, and in every other review of a Miranda SLR I’ve written. I am a big fan of Miranda cameras despite the sad fact that they don’t feel the same way about me. I like their looks, I like their feel, and I like their history. There’s something of an underdog story of the Japanese camera maker who was one of the first to make an SLR, frequently employed half-naked women in their advertising, embraced lens adapters, and offered pro-level features like interchangeable viewfinders at prices regular people could afford. If you can find a Miranda A with a chrome Soligor lens mounted for a reasonable price, I definitely recommend adding it to your collection.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Miranda_A

http://www.pentax-slr.com/71760578

https://mirandageek.eu/about-miranda

http://web.archive.org/web/20181028062856/http://www.mirandacamera.com/_modelinfo/modelinfo.htm

Another great review. I bought a Miranda DR at a flea market, basically because it looks cool and I like front shutter releases. It cleaned up well and everything works except the slow speeds. The DR has the advantage of a microprism in the viewfinder screen, which helps focusing, and a cool red leather dot in the counter dial. I wish I had one of the early lenses with the pressure-actuated diaphragm coupling to the shutter release, but the DR came with a later Auto-Miranda lens which is designed for the coupling on the Sensorex models. So I recently purchased a Miranda RE Sensomat so I could get auto stop down. The neat feature on this model is that it has both front and top shutter releases. The top one can be unscrewed to reveal a cable release socket. Following your hypothesis about Miranda problems and model age, on this one every 4 or 5 shots the mirror will stick in the up position. I have to remove the lens, jiggle the mirror, and advance the film for it to come back down. I think it’s a simple lubrication problem with a sliding lever accessible from the bottom. I can confirm the prism on the RE is the same as the early models. The RE came with an M42 to Miranda adapter so I can use my extension tubes, Takumar and Helios lenses with the Mirandas now. I’d like to find a waist-level finder now.

How did AIC spin off the Soligor line? Those lenses were on the market well into the 1970s as I recall.

The complete story of AiC and what they did in their time selling Miranda is largely a mystery. Soligor was linked to Miranda from the very beginning and had a thriving third party lens business. You could find Soligor lenses in any mount. What became of the company after Miranda’s demise however, I have no idea!

I paid my way in college with a Miranda G i bought in 1969. Still have it, although its totally worn out! Never had a single problem with it! For nostalgia sake, I wish I hadnt sold the two Tamron adaptall lenses I had for it! I enjoy your blog, keep up the great work!