This is a Noblex 135 S, a 35mm swing lens panoramic camera made by Kamera Werk Dresden, in Dresden, Germany starting in 1992. The Noblex was designed by John Noble whose father owned KW Dresden prior to World War II. After the fall of East Germany, Noble returned and reacquired the rights to his father’s company and released a series of 35mm and medium format panoramic cameras. All Noblex cameras have a unique electronically controlled rotating slit shutter that spins a complete 360º for each exposure. The camera is very nicely built and with an optional Panolux adapter, is capable of automatic exposure. The camera features a fixed focus 29mm f/4.5 lens that when stopped down, has enough depth of field to allow images from 1 meter to infinity to be in focus.

Film Type: 135 (35mm) (24mm x 66mm panoramic images)

Lens: 29mm f/4.5 Noblar T (Docter-Wetzlar) coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: Fixed, 1 meter to Infinity @ f/16

Viewfinder: 136º Field of View Optical Viewfinder with Bubble Level

Shutter: Rotating Fixed 1.4mm Slit, Electronically Controlled

Speeds: 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter (Only with Panolux Adapter): Coupled Silicon Photocell, Aperture Priority Auto Exposure

Battery: (4x) 1.5v AAA Alkaline or Lithium Battery

Battery (Panolux Adapter): (2x) 1.5v N Alkaline or Lithium Battery

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Double Exposures

Weight: 880 grams(with batteries), 964 grams (with batteries and Panolux adapter)

Manual: https://cameramanuals.org/prof_pdf/noblex_135n_135s_135u-e-g.pdf

Manual (Panolux Adapter): https://mikeeckman.com/media/Panolux135Manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Noblex 135 S is an interesting camera, both in historical significance and function. Made by a man who was incarcerated in a Soviet Gulag, who broke free and petitioned his father’s company after the collapse of the Berlin wall is a great story, but as an electronically controlled swing lens panoramic camera from the 1990s, there simply is no other. The camera is very easy to use, has a wide range of features, including auto exposure, and produces extremely good images, however reliability is in question. The design of the slow speed mechanism is prone to failure and with few options for repair, getting one of these in operating condition is a challenge. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance and no other camera like it | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

The Noblex 135 S was part of a series of 35mm and 120 roll film panoramic cameras which were produced by Kamera Werk Dresden. Technically, you could say that the Noblexes were the only cameras ever made by this company, and while you wouldn’t be wrong, the history of the company that would become Kamera Werk Dresden goes back a lot farther.

The Noblex 135 S was part of a series of 35mm and 120 roll film panoramic cameras which were produced by Kamera Werk Dresden. Technically, you could say that the Noblexes were the only cameras ever made by this company, and while you wouldn’t be wrong, the history of the company that would become Kamera Werk Dresden goes back a lot farther.

KW was founded in Dresden, Germany in 1919 by Paul Guthe and a Swiss businessman named Benno Thorsch as Kamera-Werkstätten Guthe & Thorsch. Guthe had previous experience in camera manufacturing, owning another camera factory in the Dresden area that he founded a few years earlier in 1915.

KW’s first product was a folding camera called the Patent Etui. It had an extremely slim and compact body that was quite a bit smaller than comparable cameras of the time. The word “etui” in German translates to “case” in English. There were versions made for 6.5cm x 9cm sheet film and some that used 9cm x 12cm film. The Patent Etui had an innovative and unique design that was unlike any other camera made at the time, or even in the years that would follow. This innovation would become a hallmark of KW’s legacy, setting a standard for new and unique designs and features in many of their models to come.

The Patent Etui was in production throughout the 1920s at a time when the German economy was very weak due to the outcome of World War I. Many German companies would either collapse or merge with other companies during the 1920s. In 1926, four Dresden area companies would all merge together to form one single company that would be called Zeiss-Ikon. But not KW, they were one of the few Dresden optics companies that saw great success. So much so that in 1928, KW moved from it’s original location in Niedersedlitz to a larger facility in Dresden, right down the street from Zeiss-Ikon’s factory. KW employed at least 150 employees and the company’s output at this time was around 100 cameras a day.

In 1931, KW released another innovative camera with an all new design called the Pilot Reflex. This new camera was a folding Twin Lens Reflex design that took 3cm x 4cm images on “Vest Pocket” 127 roll film. The Pilot Reflex combined the best features of a TLR like the Rolleiflex and a folding camera that when collapsed was much smaller and portable. A few years later, KW would release two more Pilot models known as the Pilot 6 and Pilot Super, both were medium format Single Lens Reflex cameras that used 120 format roll film.

Note: A large amount of the information from the next few paragraphs comes from an excellent essay on KW’s history written by T. Rand Collins MD on his blog, “Through a Vintage Lens”. I will do my best to paraphrase the relevant facts here in my own way without plagiarizing the original author’s work, while still giving him full credit for the research.

At the time of KW’s greatest success, Paul Guthe and Benno Thorsch who were both Jewish, started to feel the pressure of anti-Jewish treatment in Germany and in 1938, would flee the country. Guthe was the first to leave, selling his shares in the company to Thorsch. Very little is known about what happened to Paul Guthe after he left Germany, but Benno Thorsch’s story on the other hand, is quite fascinating.

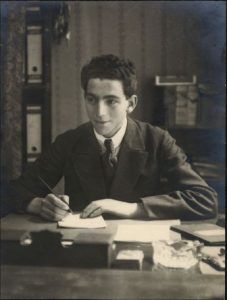

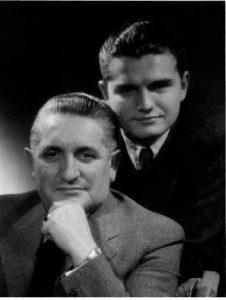

Before leaving Germany, Benno Thorsch befriended a German born American businessman named Charles A. Noble (born Karl Adolf Spanknöbel) who owned a failing photo-finishing company in Detroit where his wife worked. Thorsch would negotiate a mutually agreeable trade of KW for Noble’s failing company back in the United States. Benno Thorsch quickly left for America to run his new business while Charles Noble’s family moved to Germany to take over KW. Together with his son John, in 1939 Charles would rename the company to Kamera-Werkstätten Charles A. Noble.

Benno Thorsch would revive the Noble’s struggling film finishing business in Detroit, but would ultimately relocate out west and in 1944 would open the Studio City Camera Exchange on Ventura Boulevard in North Hollywood, CA. Benno would run the business with his son Bennie, and eventual grandson Ronald for 62 years until it closed in 2006. Benno Thorsch would live a long life, eventually passing away in a retirement home in 2003 at the age of 105.

The Noble’s story however, went in a different direction. Upon resuming business operations in 1939, Charles Noble felt that 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras were the way of the future and would hire German engineer Alois Hoheisel to help design KW’s first 35mm SLR camera, which would eventually become the Praktiflex. The Praktiflex made it’s debut at the 1939 Leipzig Fair and would generate excitement almost immediately. Demand for the new Praktiflex was so great, that the company had to quickly relocate into a former candy factory in Niedersedlitz to meet demand.

War would break out shortly after the release of the Praktiflex and the Nobles would attempt to return to America, but would be denied exit and required to return back to Dresden where they would resume operations at KW. Unlike many other manufacturing companies in Germany during World War II, it appears that KW was allowed to continue making cameras throughout the war as there exist cameras made between 1940 and February 1945. In fact, at least one variant of the original Praktiflex was made for the German military. Military issue Praktiflexes were engraved with “M 309” on the bodies and all lenses associated with it. Whether KW also produced other, non-optics products for the German war effort is unknown.

In four separate bombing raids on February 13th, 14th, and 15th, 1945, Allied bombers unleashed an unprecedented attack on Dresden, likely because of it’s manufacturing and transportation capacity. 722 bombers from the British Royal Air Force and 527 from the United States Army Air Forces dropped a combined 3900 tons of bombs and incendiary devices on the city. The “shock and awe” firestorm resulted in the complete destruction of over 6.5 square kilometers of the city’s center and a widely disputed number of deaths. Some German sources at the time claimed that between 200,000 and 500,000 people died in the attacks, but a 2010 study by Matthias Neutzner suggested a number closer to 25,000 was more accurate. Whichever number is correct, the bombing of Dresden has become a point of contention and controversy that continues to this day due to the apparent overkill of the mission.

The KW factory was spared total destruction, likely because of it’s location in nearby Niedersedlitz, as opposed to the city center like most other optics companies of the time. Praktiflex production would resume after the Dresden bombings for at least another year.

Dresden is located in what would become Soviet controlled East Germany. Upon occupation of Soviet forces in Dresden, KW would become a state owned entity known as VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz. The abbreviation VEB stands for Volkseigener Betrieb which translates to ‘Publicly Owned Operation’ in English and was the main legal form of industrial enterprise in East Germany from the late 1940s until the early 1960s.

KW had been successful at making all of their own camera bodies, but they never made any of their own lenses. The lenses were all sourced from Carl Zeiss Stuttgart and Schneider-Kreuznach, both companies who were located in the western part of Germany, which after the war would become Allied controlled West Germany. As a result of the new alignment of the two separate countries, KW needed to re-negotiate a deal with Zeiss in order to buy lenses for future KW cameras. In 1946, after considerable negotiations with the Soviet government, Charles and John Noble were granted permission to travel to West Germany to formulate an agreement for them to continue purchasing Zeiss lenses.

Upon their return to Dresden however, both Charles and John Noble were arrested under unfounded suspicions of espionage and sent to prison camps in the Soviet Gulag system. The conditions in the forced labor camps were abysmal. Starvation and executions were common practice, and both Nobles relied on their religious background to stay alive. Charles and John were kept together in the same prison camp until 1950 when John Noble, who was 26 at the time, was given a 15 year sentence and sent to a variety of different Soviet prison camps, one of which was the Soviet Special Camp No. 2 which was formerly the Nazi Buchenwald concentration camp. Noble would eventually wind up in town called Vorkuta in northern Siberia where he mined coal with over 100,000 other prisoners.

In 1952, Charles Noble would be released from prison, never to return to KW or Dresden again. He would at first live with relatives in West Germany, but eventually make his way back to the United States where he worked as an adviser to the photography department of General Motors. He would die in May, 1983 at the age of 90.

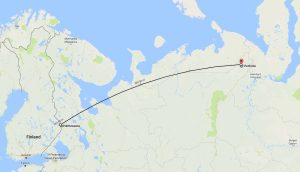

John’s situation however, was much worse. Conditions in the Gulag camps were beyond bad. The town of Vorkuta where Noble worked is located within the arctic circle and average winter temps don’t get any higher than -20°C, with occasional drops to as cold as -52°C. Death among the prisoners from starvation and freezing were common. To cope, prisoners would huddle together at the bottom of coal pits in an effort to salvage any body heat they had. Years later, John Noble would say that during his stay in Vorkuta, he weighed less than 100 lbs as he was kept on a starvation diet for months at a time.

In the early 1950s, John’s whereabouts were unknown to his family and multiple requests to the state department yielded no answers. Then in July 1953, shortly after Stalin’s death, in a twist that seems like it should have come straight from a Hollywood action movie, John Noble took part in an uprising among prisoners from multiple Gulag labor camps.

Somewhere around 400 prisoners would take over four different camps staging an escape, and then embarking on a nearly 1000 mile walk towards Finland. A month after their escape, the prisoners would be caught, and for their crimes, most would be executed. Somehow, John Noble would be spared execution and sent back to prison.

A year later, Noble would manage to sneak a postcard addressed to his family by gluing it to the back of some other mail that was being sent out. The postcard would manage to make it’s way to some of Noble’s family living in West Germany who then notified the U.S. Government of his location. Since John Noble was born in Detroit, MI before his family purchased the KW factory from Benno Thorsch, he was an American citizen and this prompted the Eisenhower administration to contact the Soviet government and demand his immediate release.

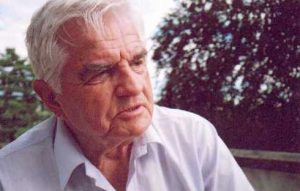

In January 1955, along with several other American POWs, John Noble would be released after nearly 10 years in prison for a crime he never committed.

After his release, John Noble would first give several press conferences in West Berlin, detailing his experiences and the horrific treatment he and other prisoners suffered at the hands of the Soviet Gulag system. Three days after his conference, in an attempt to discredit Noble and his family, the East German government would issue a statement in their national newspaper making the absurd accusation that John’s father Charles helped coordinate the Allied attacks on Dresden in February 1945.

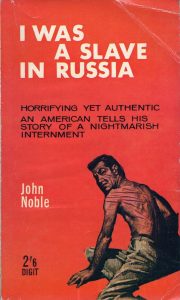

Shortly after, Noble would return to the United States, giving multiple lectures about his time in prison. He felt he had a duty to tell his story about the consequences of dictatorship and the contempt for humanity which he suffered. In 1958, he would publish a book called “I Was a Slave in Russia” which was a best seller at the time, selling nearly 1.6 million copies upon it’s release.

John Noble would spend the next several years as a speech writer and political consultant in the United States. He became a beacon of hope for human rights, and helped to raise awareness of other prisoners in Soviet camps. In 1979, he was knighted for his persistent and tireless efforts towards the benefit of humanity by the French Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem.

A short YouTube documentary below summarizes John Noble’s story as a prisoner and gives a preview to both a film and a book written by Noble in 2005, called Verbannt und Verleugnet (Banished and Vanished).

Warning, this video has some pretty gruesome images in it.

After the reunification of Germany in 1990, Sir John Noble would return to Dresden and attempt to reclaim the rights to his father’s old company. Although unsuccessful at attaining KWs patents or the Pentacon name, he would be awarded the property of one of KW’s factories in Dresden where he would relaunch KW as Kamera Werk Dresden.

Now in charge of his father’s company for the first time in nearly half a century, work began on a new series of panoramic cameras which would eventually bear John Noble’s name. Unlike other swing lens or fixed lens panoramic cameras that had been created in the years prior, the Noblex would be the first to use an electronically controlled drum, that rather than rotate one direction and then return to it’s original position in the opposite direction, the new camera’s drum would rotate in a full 360º back to it’s starting position.

The work on the actual shutter was done by Hans-Jörg Schönherr and Hans Zimmet. German patents, and eventual US patents bear both men’s names as inventors. It is not clear what role John Noble actually had in the creation of the camera, but at the age of nearly 70, it is possible he only offered consulting opinions.

Noble’s new camera, the Noblex, would support different film formats, and using modern technology could make exposures in extremely low light and with an optional exposure meter, could expose the image at variable speeds in different areas of the image.

Swing lens cameras usually operate on the basis of some type of spring loaded design in which the lens “sweeps” across a curved plane with only a small slit of light passing through to make an image. Shutter speeds on swing lens cameras are notoriously misleading as speeds are given in “equivalent” speeds compared to a standard camera, when in reality total exposures are much longer. A 1 second exposure on Noble’s new camera would take a total of 128 seconds to complete.

Great care was put into making the Noblex the best camera it could be, but it’s design had a critical flaw. Although the movement of the shutter was controlled by an electronic motor, the coupling between the output shaft of the motor to the actual drum was via a large plastic wheel with a wax-like substance on it’s outer edge. This “friction wheel” design eliminates lash between the teeth of a geared wheel, allowing for smoother movement of the drum as the exposure is made. Although the concept likely made sense during the development stage, problems with the friction material began to appear almost immediately.

As early as 1994, some cameras started to show failure of the friction material as when the camera sat idle, the output shaft of the electronic motor made constant contact with the soft waxy substance, creating divots in it. As the years went by, the friction material would degrade and eventually fail. In the years since Noblex cameras were released, most have since failed and without many people willing to work on then, getting a Noblex repaired is extremely difficult to do. If you do manage to find someone who can repair one, replacing the original friction material with something more durable, such as silicone O-ring would likely prolong the life of the camera much longer than the original material did.

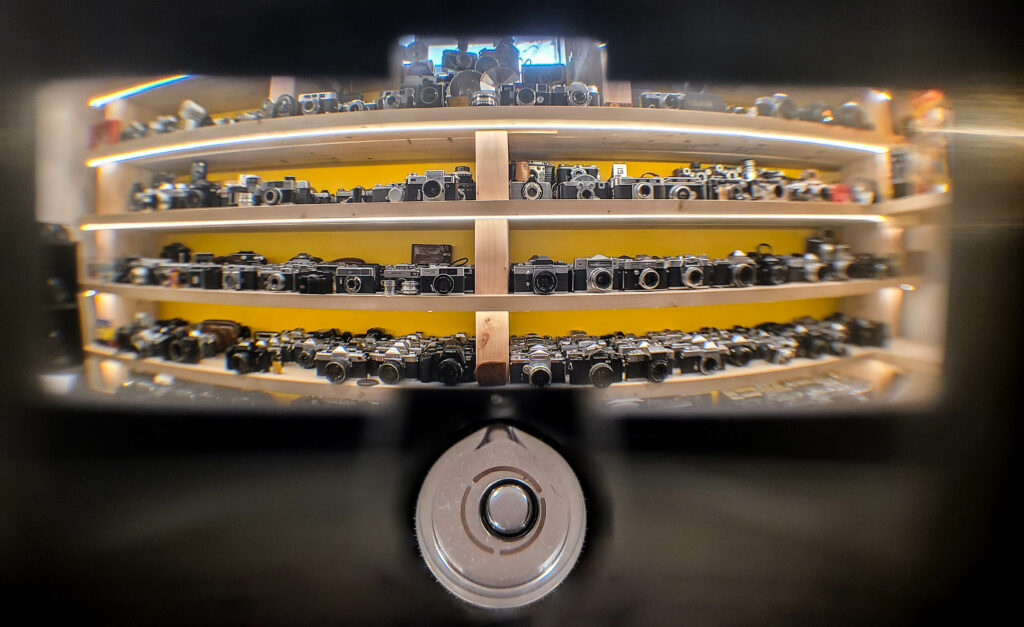

In the image to the right, the friction material on the outer edge of the flywheel is completely falling apart. The metal output shaft of the electronic motor can be seen in the foreground.

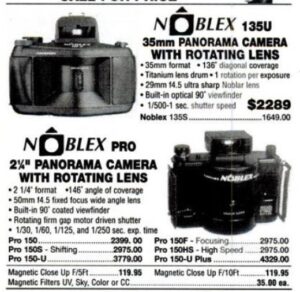

When it was released, the medium format Noblex 150 models came first with the 35mm versions later. A total of four different versions of the 35mm Noblex 135 were released, all featuring the same electronically controlled swing lens, 29mm f/4.5 lens, and 24mm x 66cm exposure size, but with different features. In order from most to least advanced, they were:

- Noblex 135 U – Top of the line model with shutter speeds 1 – 1/500, lens shift feature, multi-exposure mode, bubble level in viewfinder, and support for Panolux exposure meter

- Noblex 135 S – Same as above, except only shutter speeds 1/30 – 1/500

- Noblex 135 N – Same as above, but omits lens shift feature and support for Panolux exposure meter

- Noblex ProSport – Simplest model, also lacks multi-exposure mode and bubble level

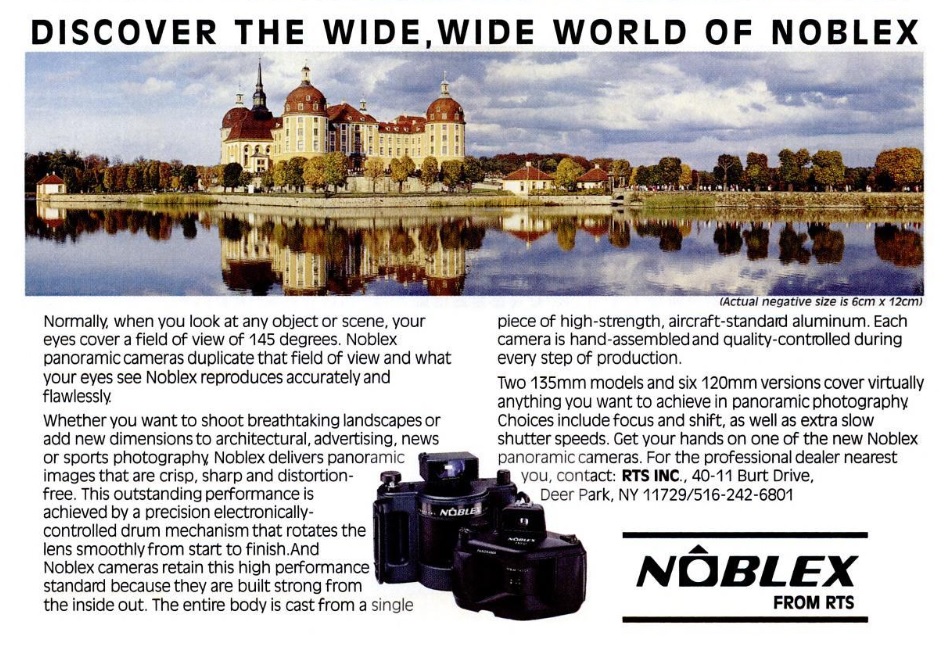

When new, the Noblex models carried a hefty price tag. Panoramic cameras of all kinds were largely used by professional photographers, so the high price was to be expected, but for the unprepared, sticker shock was quite high.

In an ad for B&H Photo from the May 1996 issue of Popular Photography, the medium format Noblexes range in price from $2399 to $4329 and the Noblex 135 S and U models were $1649 and $2289 respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these four prices are $4580, $8270, $3150, and $4370 respectively.

Although not shown in this ad, the later Noblex ProSport would be released later with a retail price of $995, making it the most affordable option.

The Noblex panoramic cameras were produced for quite a long time as they were the only commercially available swing lens cameras anywhere in the world. Although I could not find an end production date, camera-wiki suggests they were still being produced as recently as 2012. The same article goes onto say that a 4×5 large format prototype called the Prestoflex 4×5 was sold in June 2017 at Westlicht. The camera was listed as being incomplete, so whether or not this was an actual prototype intended to be produced, or if it was a custom made one-off, combining a monorail with a Noblex style swing lens, is not clear.

Although the Noblex would outlive it’s creator, Sir John Noble would continue to give lectures on talk shows, schools, and at other public speaking events up until his death on November 10, 2007. He was survived by his wife, 5 children and 9 grandchildren. His body was buried at the Waldfriedhof Weisser Hirsch cemetery on the edge of a large forestry area near Dresden.

Today, there is a limited but enthusiastic level of interest for panoramic cameras. Models like the Hasselblad XPan, Fujifilm G617, and Kodak No.1 Panorams routinely go for very high prices as people yearn for cameras that can deliver results no other camera can.

When it comes to swing lens cameras, the discussion is almost always one of many Soviet Horizont models produced over the years, but the Noblex isn’t discussed quite as often. Although they’re a much newer model, their extremely high prices and how quickly 1990s film cameras were over shadowed by the rise of the digital camera, the Noblex seems to be somewhat of a forgotten model, which is a shame as they’re well built and interesting cameras with features not found on any other camera. I’ll warn you however, that a lack of interest does not mean low price. When Noblexes do show up for sale, especially the higher end models, prices can get extremely high!

My Thoughts

Who doesn’t love a panoramic camera? The appeal of an image that can capture a wider than 100 degree field of view is immensely exciting. In my time shooting cameras, I’ve had the pleasure of trying everything from a No.1 Panoram-Kodak to a Hasselblad XPan to a KMZ Horizont. I’ve shot American panoramics, Japanese panoramics, and Soviet panoramics. So I guess it was about time I try one from a German company. But how many German companies made panoramic cameras?

I’ll answer that one for you, one. And the company that did it might surprise you. KW, not the KW that made the Praktina SLR or the Pilot TLR, but the KW that was resurrected in the 1990s after the Berlin Wall fell, and the son of the original owner, John Noble, petitioned to get his factory and trademarks back.

After a long hiatus that saw him go from camera innovator to Gulag prisoner, when John Noble decided to make cameras again, he chose swing lens panoramic cameras. I had an opportunity to test one of these on loan from my friend, and frequent enabler, Kurt Ingham who literally sent this to me without telling me what was in the box. So when I opened it up, I was excited to give it a go.

The Noblex 135 S is a modern camera, made in the 1990s and it is covered in black plastic, much as you’d expect a camera from the 1990s to be made out of. What isn’t expected however, is the heft of this camera. Weighing in at 964 grams or just over 2 pounds when equipped with the Panolux exposure meter and batteries, the Noblex is unexpectedly heavy. This gives the camera a reassuring heft, suggesting this is a precision instrument, rather than a gimmicky toy like some panoramic cameras like the Holga 120 Pan. The camera is understandably tall, considering it makes images nearly twice as wide as that of a normal 35mm camera, and with the large built in viewfinder, is quite tall.

Up top, the camera takes on a triangular shape, not unlike an Exakta in which the middle of the camera sticks out farther than the edges. Unlike the Exakta however, the right side has a prominent hand grip which makes holding the camera easy. Starting on the left is the manual rewind knob with fold out handle. Like many 35mm cameras from years before it, lifting up on the rewind knob also opens the film compartment and lifts the cassette fork out of the way for film loading.

In the middle of the camera is what looks like a hot shoe, but actually isn’t as the Noblex does not have any type of flash synchronization. Instead, in the center of the shoe is a small glass circle that covers a bubble spirit level which is visible from within the viewfinder which helps the user ensure the camera is level. Also inside of the shoe are two electrical contacts which are used for the optional Panolux exposure meter which slides in this shoe.

To the right of the viewfinder hump is a sliding multi-exposure button for intentional double exposures, an LED power button which glows green when the camera is on, a digital exposure counter with a reset button next to it, a large film advance knob, and finally the combined shutter speed dial and cable threaded shutter release button. The exposure counter goes upward from 0 to 19 which is the maximum number of exposures you can fit on a 36 exposure roll of film and must be manually reset after loading in film. The shutter speed dial on the Noblex 135 S has speeds from 1/30 to 1/500, plus a green A setting which is used with the Panolux exposure adapter. You may set the camera to A mode without the adapter, but the camera will not exposure your images correctly. If you have the Noblex 135 U model, you have additional slow speeds down to 1 second.

If you’ve never used a swing lens panoramic camera before, it is very important to understand that the shutter speeds are “equivalent” shutter speeds at the point where the film is being exposure, but since the entire 66mm exposure isn’t be exposed at the same time, it takes additional time for the lens to stop swinging. As a result, shutter speeds require extra stabilization to prevent distorted images. At the 1/30 setting, a full 4 seconds are required to make the whole image, at 1/60, it takes 2 seconds, at 1/125 it takes 1 second, and so on. If you have the Noblex 135 U with the additional slow speeds, a 1 second exposure requires a total of 128 seconds to complete!

I made a short video which shows the continuous 360º rotation of the drum with the multi-exposure mode activated. In this video, I show the shutter firing at three speeds, 1/500, 1/125, and 1/60. Notice that at a still pretty fast 1/60 equivalent shutter speed, the drum still takes a full 2 seconds to complete it’s motion.

The bottom of the camera has a sliding power switch for tuning the camera on and off, a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, and the rewind release button. The tripod socket is part of a larger metal plate which feels very sturdy and most likely is connected to some inner part of the body, offering good stabilization.

The right side of the camera gives you a look at the solid rubber hand grip and the battery compartment. Below the battery compartment is a small loop with a wrist strap, which I find a little odd as the camera is quite heavy, and likely would feel uncomfortable hanging from your wrist for more than a few minutes. Had John Noble consulted me when designing this camera, I would have definitely recommended normal strap lugs on both sides of the camera. A round knob with a slot in the center for a coin, unscrews to reveal where the four AAA batteries go. For my test, I used regular alkaline AAA batteries, although I am sure modern lithium batteries would likely work well too. The camera’s user manual strongly suggests in bold letters not to use rechargeable batteries or to mix batteries of different types.

Around back, there’s little to see other than the large rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder and a plaque identifying the camera as being made by “Kamerawerke Noble GmbH Dresden”. The right side of the door and edge of the camera has an ergonomic hump that adds comfort to your right hand as it grips the camera.

There are a lot of oddities about the Noblex that differ from just any old 35mm camera, but one thing it shares in common is opening the film door. Lifting up on the rewind knob and giving it a firm tug releases the door latch. The right hinged film door swings open to reveal the large film compartment. Like all swing lens panoramic cameras, the film plane in the Noblex is curved, so that the distance from the lens to the light sensitive film is constant as the image is exposed.

Also like other swing lens panoramic cameras, the path the film takes requires a little bit of understanding before you load your first roll. You cannot simply load in a new cassette, stretch it across the compartment and attach the leader to a take up spool.

Film transports from left to right, and although loading in a new cassette is no different from other 35mm cameras, you must pass the leader behind the sprocket shaft to the right of the film gate. In the image to the left, you can see the shaft to the left and behind the take up spool. The only way to make the gears turn is by advancing the film knob. By doing this, it will pull the film behind the shaft and transport it behind the sprocket and it wrap it around behind the take up spool. Once you’ve advanced enough film, you should be able to take the leader and attach it to the take up spool from the right. The fixed take up spool has a total of four slits, one of which you must insert the tip of the leader in to attach it. With the leader attached to the spool, manually rotate the spool clockwise using your fingers until enough of the film has wrapped around itself to be secure.

Like all cameras, fire off a blank exposure to make sure the film is properly attached before closing the film door. On the inside of the door, a raised bar presses down on the film around where it comes out of the film cassette, forcing it to take shape around the curved film plane. The door itself will hold the film taught across the film plane, so there is no need for a regular film pressure plate. Although the Noblex is generally well built, the entire film compartment and door are made of plastic, so special care should be taken not to put stress on the door hinge as it is open as I could see it possibly cracking if mishandled.

By itself, the Noblex 135 S is a manual exposure camera. Automatic exposure can be achieved with the Panolux adapter, but more on that later. Without it, the shutter speed dial offers five speeds from 1/30 to 1/500. Up front, the front of the curved lens barrel has a sliding dial which controls a traditional diaphragm on the lens. Aperture sizes from f/4.5 to f/16 are selectable. In addition to the available f/stops, you’ll notice marks with the letters “S” and “O” on the same dial. These are settings for lens shift which allow for a higher viewpoint without having to tilt the camera. The Noblex manual does not specify what the letters “S” and “O” mean, other than to state “O” is the normal position and “S” is the shifted position.

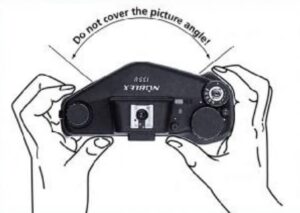

Also on the front of the camera are rubber grips for positioning your fingers while holding the camera. The Noblex exposes an image with a very wide 136º Field of View which is much wider than that of the Hasselblad Xpan, which using the widest lens available for that camera, is only 94º, and wider than that of the KMZ Horizont swing lens camera which is 120º. As a result, it is very easy to accidentally include your fingers in the exposed image, so special care must be taken to ensure your fingers are in the correct location to prevent this from happening.

The viewfinder is large and bright and shows an approximate of the entire field of view of the camera. Since the viewfinder is just a simple optical design, it does not perfectly reflect what will be captured on film. Looking at the extreme sides of the viewfinder, there is considerable distortion as a result of it’s simple optical design. This distortion will not appear in the final image. Also, you cannot see obstructions to the lens, such as your fingers as this is not a Through the Lens viewfinder.

Conveniently located at the bottom of the viewfinder is the reflected bubble level located in the center of the accessory shoe, mounted on top of the camera. Unlike regular cameras, using the bubble level is critical in getting good panoramic shots, especially those where the horizon is visible. It can be a challenge getting the framing you want, plus the bubble level perfectly centered, but with practice, it does get easier. In use, it is very easy to compose your image through the viewfinder while also seeing the bubble level, without having to reposition your eye.

The Noblex 135 S is a unique camera. If you’ve used a swing lens camera before, there should be a lot of familiarity here. Making sure to hold the camera correctly so as not to expose your fingers, getting the camera perfectly level, and understanding that a 1/30 shutter speed requires a much longer total exposure are all things you probably already know if you’ve shot a KMZ Horizont or some other similar camera.

If however, this is your first experience, it is going to take some time. John Noble and his team did a remarkable job of making a modern swing lens camera with 1990s conveniences, but no matter how much they might have tried, this camera does not shoot like other cameras, especially not like fixed lens panoramics like the Hasselblad Xpan. You’ll definitely need to read the manual and probably even sacrifice a few test rolls before you get the hang of it. But once you do, boy, what a camera!

The Panolux Adapter

An accessory that was available for the Noblex was the Panolux adapter. Noblex made a variety of Panolux adapters for various Noblex cameras, and I’ve read that most work on most models, but I cannot guarantee compatibility as I only have one, which is the Panolux 135. A very similar model called the Panolux 150 looks very similar, and may or may not work. The Panolux 135 I have here has two light meters, a front facing cell that measures light on the subject the meter is pointed at, and a top mounted meter under a frosted dome for incident light. Various modes of the Panolux use one or both meters. The Panolux is also capable of variable speeds in which the drum rotates faster or slower during different parts of the exposure. Reading the instruction manual caused my head to spin. I really struggled to understand the different models, as it sometimes sounded like the Panolux does this variable exposure speed automatically, but in others, you need to manually set it to do it.

Each Panolux adapter requires it’s own power source, which for this model is two Type N (LR1) Lithium batteries. Type N batteries became popular as “camera batteries” in the 90s before dedicated rechargeable batteries took over, and although are still made today, are quite expensive, so before considering getting one of these, make sure you have two on hand.

At first glance, using the Panolux seems easy enough. A short guide to using the adapter is listed above walking you through everything you need to know. In an effort to not repeat everything here, some key takeaways are that you must first attach the Panolux adapter to the camera to the shoe with the camera off. Once it is connected, turn on the adapter and calibrated it to whatever film is loaded in the camera and whichever f/stop you intend to use. Once this is done, turn on the camera and set the shutter speed dial to the green “A” setting.

The Panolux works in two modes, reflected and incident light modes. These two modes are selected via the red power switch near the bottom center of the adapter. With the red switch in the center position, the Panolux is powered down, but sliding the switch to the left puts it into reflected mode, and to the right into incident mode. With the adapter in either position for 5 minutes without any activity, the Panolux will automatically power down. To wake it up, you must move the red switch to Off and back to your chosen mode again.

The next set is to calibrate the adapter to the speed of film loaded into the camera. To do this, press and hold the ISO button until one of the LEDs on the grid blinks red/green. Once this happens, press either of the up or down arrow buttons to select your ISO film speed from 25 to 6400. Once you’ve selected the correct film speed, wait 3 seconds for the LED to stop blinking and the film speed is set.

The Panolux is not coupled to the diaphragm of the lens, so you must tell the Panolux which f/stop you have selected on the lens and make sure it matches. On the Panolux, a lower case letter ‘k’ is used to mean f/stop. Set your chosen f/stop similar to how you set the film speed by first press and holding the ‘k’ button until one of the LEDs starts to blink red/green, then by using the up or down arrow buttons, select an f/stop between f/4 and f/16. Although an option for f/22 exists on the Panolux, the Noblex 135 S does not offer this setting. Once you have made your selection, wait 3 seconds for the LEDs to stop blinking and the aperture is set.

While testing this camera, I put in a type “N” battery into the Panolux and it lit up. I clipped it onto the camera and set it into Auto mode and, pressed the shutter release, and it fired, but I had no idea if it was working properly. I removed the Panolux, but left the camera into Auto mode and fired the shutter, and once again, it fired at what looked to be the same speed. I put it back on and tried the camera both in bright light and indoors, hoping to see some sort of difference in the speed at which the shutter fired, and I couldn’t tell a difference.

Either I was doing something wrong, or the meter wasn’t working. I read through the PDF manual once again, and it seemed that each time I read it, I got more confused. Discouraged, I disconnected the Panolux, took out the battery, and put it back in the box, and continued to use the Noblex in manual exposure mode. While the promise of an automatic exposure swing lens panoramic camera is enticing, it gave me a headache thinking about it, so I didn’t use it any further. If you have one of these adapters, and you’ve had good results with it, please share in the comments.

My Results

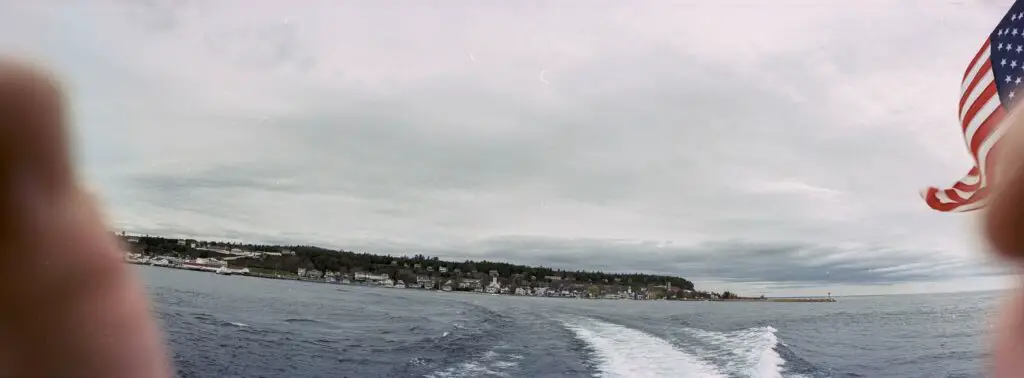

Shortly after the Noblex arrived, we had a family trip planned to northern Michigan and expecting to see the Mackinac Bridge and parts of the Great Lakes, I figured a panoramic camera would be ideal. I quickly loaded in a roll of Kodak Ektar 100 and threw it in the bag. Sadly…in my rush to get using the camera, I didn’t spend as much time as I should have with the user manual and didn’t completely understand how the shutter speeds worked, or that you actually needed to use the Panolux adapter for the camera to work in Auto mode. Despite my best efforts to ruin the entire roll, I still managed some shots, which I’ve shared below, but knowing that I needed to actually RTFM and not rush such a unique camera, I set it aside, waiting for another opportunity to devote the necessary time the camera requires.

To be fair, the Noblex isn’t a difficult camera to use, you just need to familiarize yourself with it’s controls, how to properly hold the body so as not to expose your fingers, and you need to somewhat program your brain to “see” in panoramas. I failed to understand getting the right exposure in a number of shots like the school bus and cabin pictures, I didn’t use the bubble level correctly in a few images, and of course, my fingers are visible in nearly every image. I likely could have cropped out my fingers in most and still had a decent panorama, but if I have a camera with a 136º field of view, I want to use all 136º.

Simply using the Noblex as if it were a point and shoot camera with a very wide angle lens, you’ll miss the point, ruining what could be beautiful compositions with uninspired bland photos. I knew I had to do better, so for my second roll, I loaded in some fresh Fuji 200 and took it out with me in early spring 2023.

After looking at both galleries of images, a few things are evident. For starters, it is VERY easy to expose your fingers while using this camera, so it is absolutely critical that you pay attention to how you hold it while shooting. This requires gripping the camera with your fingertips in a way that is less secure than with your whole hand. Even though I was aware of this, I still managed to expose my fingers on the second roll.

While I never once dropped the camera, I would definitely recommend having the wrist strap wrapped around your wrist to avoid any unfortunate falls. I am certain that with time, holding the camera properly becomes second nature, but to those new to this camera or who only shoot it sporadically, it is something that you really need to be mindful of.

A second thing that’s evident is that this camera makes very good images. I do not have a very thorough understanding of optics and how a lens relates to sharpness. Generally, most lenses are sharpest in the center, and depending on their complexity, can get softer near the edges. With a swing lens camera, the lens only exposes a small slit of film at any one time. As the lens swings across it’s entire motion, it exposes the film sort of how a windshield wiper wipes away rain. In my mind, I believe that since only the center part of the lens is what makes the entire exposure, you get the benefit of a sharp image all the way across the image. This not only improves sharpness across a very large image, but it almost completely eliminates softness and vignetting in the corners, as is common on panoramic cameras that rely on ultra wide angle lenses like the Hasselblad XPan.

A final consideration when shooting a swing lens camera, is that composition matters. With the extreme width of the 136º Field of View and the distortion of the curved field, simply pointing the camera at random subjects and pressing the shutter release will not always produce a pleasing image. An understanding of swing lens panoramic photography is necessary to reprogram your brain to see your compositions before you make them.

Oh, and one more thing, vertical panoramas are very difficult to make look good.

Noblar or Docter? Everything I’ve read online about the Noblex 135 S, including a PDF owners manual credited to Kamera Werk Dresden describe the camera’s lens as a Noblar T 4,5/29, however looking at the physical lens itself, the name “Docter-Wetzlar-Germany” is printed around it. Are the names Noblar and Docter the same thing? Was there some kind of mid-model change from one lens to another? Do I have some kind of super rare variant with a different lens? I don’t know! If you know more about this name confusion than I do, please let me know in the comments!

On paper, the 4-element Docter-Wetzlar lens might not sound terribly exciting, but the images it makes are outstanding. Sharpness is excellent in every image. While I expected to see some softness near the top and bottom, it is not obvious. Colors and contrast were both excellent, and there were none of the typical optical anomalies associated with lesser lenses.

Beyond the need to hold the camera and get the exposure correct, using the Noblex is pretty straightforward, and makes getting panoramas very easy. That it used an electronically timed shutter definitely helps as the spring controlled designs of swing lens cameras from decades prior were notoriously inconsistent. I noticed no banding or uneven exposures in any of the images I shot.

One feature of the camera that I didn’t spend much time with was the multiple exposure feature, in which you can hold down the shutter release and the lens will continue to swing in a 360 degree circle, exposing the film over and over for as long as you hold it down. This can be used as a substitute for exposures slower than 1/30 on the Noblex 135 S which doesn’t natively support it. Another very interesting use for this feature is explored by Marko Kroeger of zeissikonveb.de in his review of the Noblex in which he would re-expose the same frame over and over again in scenes where there were people walking or cars driving by, waiting for the scene to clear before making another exposure. This in effect, can erase moving objects from an exposure as each exposure is made only when the scene was clear. Be sure to check out his review for some sample images where he put this feature to good use.

Without a doubt, the worst part of this camera is that finding them today in good working order is not easy, and will only get worse as time goes by. As I mentioned in the history section above, a fatal flaw of the design of the camera is that there is a friction wheel with a wax-like substance on it that degrades over time and when it does, it will cause uneven exposure or complete failure of the system. Around the start of the 20th century, very few technicians would take on these cameras and that number has to be very small today. As I write this, I only know of Precision Camera Works in Lakeway, TX who specifically state they can repair Noblexes. If you have one that is in need of repair, you might want to check with them.

It is clear that the Noblex 135 S, and likely all of the Noblexes, are outstanding cameras that in the 1990s when they first debuted, re-introduced the world to swing lens photography. Whether you should buy one today is a tricky question. Reliability concerns aside, before plunking down what will likely be a huge sum for any panoramic camera, you really need to understand the differences between swing lens cameras and those with ultra wide angle lenses as each has significant advantages and disadvantages. For those in the market for a Hasselblad XPan, but cannot afford one, or anyone who wants the unique look of a moving lens the Noblex is a great option, but only if you can confirm it works.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Noblex

https://zeissikonveb.de/start/kameras/noblex.html (in German)

https://luminous-landscape.com/noblex-135u/

http://jameslwatt.com/blog/2019/8/27/noblex-135-and-brunswick-festival

Thank you, Mike, for a review that shines a light on John Noble, a humanitarian as well as a talented engineer.

Great review, as always. The multiple exposure capability surely opens new ‘vistas’ of low light photography

Yeah, being able to keep rotating the barrel around and around to accomplish the equivalent of slow shutter speeds, means you can shoot this camera in very low light and still get properly exposed images. I haven’t tried this yet though.

Excellent article Mike. Having owned/used/repaired many panoramic cameras over the last 35 years you’ve summed up the Noblex well. An excellent and capable camera (and the easiest to load) with a fascinating history

Glad you enjoyed it! I definitely will shoot this camera again.

Great, entertaining review about a cool camera and a fascinating man. The construction of the camera does make it seem like an expensive, ticking time bomb. I recently got a Bronica ETRS with a 135W panoramic back, and it’s a breeze to use, without having to worry about the issues of a rotating lens/shutter. I’ll stick with that.

Interesting, in-depth review of a camera that I’ve been using for over 20 years!

Back in 2002 I wanted to get a panoramic camera and was debating between an XPan, Mamiya 7II with adapter, Noblex or one of the other mechanical swing-lens cameras…and I went with the Noblex. I bought it new, and still use it and love it. I’ve made so many great photos with this camera over the years.

Mine started to show evidence of this known drive-wheel issue quite early – I sent it back to Kamera West Dresden two times in a row in 2006. They claimed to have fixed it, but it was still sometimes temperamental, especially at the slowest 1/30 shutter speed. In 2020, the camera seemed to go really haywire, and I thought I’d finally have to send it to Precision Camera Works for an expensive repair. First though I decided to open it up and take a look myself. I finally understood what the whole problem was, and I felt like I could give a repair a go myself. I bought some silicone O-rings online for a few pounds and after fitting them, the camera has never been working better – such a delightful, satisfying experience.

I have to mention one thing which you’ve missed in your history of this company and camera – the chief designer was not John Noble at all, but a man called Kornelius Schorle. There’s a video on YouTube – reference gVKXcFK8iFo – where he talks about designing the camera over a period of 20 years.

You missed mentioning a few Noblex 135 models… around 2004 KWD introduced the 135C and 135UC – these were really just minor upgrades to existing models. If I remember correctly, the main changes were simply that the power switch was moved from the baseplate to the top of the camera, and also there was some kind of auto shut-off after a period of inactivity, to avoid unnecessarily draining the batteries – similar to how the Panolux works. If interested, you should be able to find all this info by visiting the original KWD website <www.kamera-werk-dresden.de> through the Internet Archive.

Speaking of the Panolux, I have this accessory and it works brilliantly – though, I will admit, it’s really quite unnecessary. I managed for years without it – metering separately, which is no big deal. You say you didn’t notice any difference in the duration of the drum rotation whether you used the Panolux or not. Well, I can say that there is something very wrong going on then. If you set the camera to ‘A’ and the Panolux is not mounted at all, the drum rotation is super quick – quicker even I think than when 1/500 is manually selected. So with the Panolux mounted and let’s say you’re shooting in duller conditions – the drum should rotate noticeably slower. If it rotates at high speed, something is not working right.

You wrote, “At the 1/30 setting, a full 4 seconds are required to make the whole image, at 1/60, it takes 2 seconds, at 1/125 it takes 1 second, and so on.” Yes, the exposures take some time, but I don’t think it’s quite as slow as you claim. In your own video, when you select the 1/60 shutter speed, you make 3 exposures in quick succession, taking about 4 seconds total.

I agree that the camera lacks a second strap lug. I use one of OP/TECH USA’s “SLR wrist straps” – I don’t leave the camera dangling from my wrist though, but if I’m ever taking a photo from a height, then the strap just provides a little reassurance with regard to avoiding dropping the camera! I took a photo from the top of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris and had one of those shuddery moments where I imagined the horror of the camera slipping from my hands onto the ground below (and possibly killing someone!)

Your sample photos make me cringe 🙂 with your fingers appearing in almost every photo. There is a nice slot for your right middle finger – don’t deviate from this slot 🙂 As for your left hand – don’t hold the left side of the camera at all – just support the camera underneath with your left hand – it helps to extend just your left thumb and left index finger. I have a lovely shot of the Statue of Liberty taken from a helicopter above…but the camera was quite new to me at the time and the photo is spoiled by my finger appearing in the frame similar to yours.

You write, “Around back, there’s little to see other than the large rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder and a plaque identifying the camera as being made by “Kamerawerke Noble GmbH Dresden”.” It sounds like you got an early model. Later models had that little plaque updated to show a handy little depth-of-field chart for the various aperture settings (as well as the later company name – Kamera Werk Dresden).

“The Noblex manual does not specify what the letters “S” and “O” mean, other than to state “O” is the normal position and “S” is the shifted position.” Even though they’ve printed an “O” on the camera, the manual actually has 0 (zero) printed in it. So I think the “S” means Shifted and the “O” should actually be interpreted as a zero. (Little aside – 10 Downing Street famously has a “one” and the letter “O” instead of a “zero” on the door.)

About the lens… I’ve also seen different examples with different lens labelling. I think it was changed throughout the camera’s production run. I’m not sure what the exact explanation is here, but it’s worth keeping in mind that with the division of Germany, also came the division of the Carl Zeiss company – there was Carl Zeiss Jena (in East Germany) and Carl Zeiss Oberkochen (in West Germany). I believe that, after the reunification of Germany, the optical company “Docter Optic” acquired one of Carl Zeiss Jena’s plants, where they made Tessar lenses, which were supplied to KWD for Noblex cameras. It’s possible that, as intellectual property laws were ironed out after the reunification of Germany, that Docter Optic had to give up using the trademarked “Tessar” name. I’ve seen Noblex cameras with the lens labelled “Tessar”, cameras with the lens labelled “Noblar”, and I think also ones labelled simply “T”. I don’t believe the lens design/formula itself was changed.

One final point – not on the camera at all, but an editorial comment… I know it’s minor, but I found it very distracting that you keep writing “it’s” when it should be “its”. Otherwise an excellent article.

Thank you for your thorough comments, which make a good addendum to Mike’s original article.

I’m curious to know why you chose a panorama-format camera that shoots on relatively small 35mm film and relies on complex mechanics to function … when the Fujifilm G617 is an available alternative.

Obvious: cost and size. I wanted a travel camera, and my Noblex has been around the world with me. 617 cameras are enormous, heavy and slow. Tripod essential, and probably a dedicated suitcase too. I did consider an XPan, which is a bit like a smaller format 617 camera – I put a roll of film through one, but I just didn’t like it – despite the perennial hype. The Noblex has been wonderful – I love its perspective and the results I get. (I’m not a fan of wonky horizons though – but the bubble level is there in the viewfinder to handle that.)

Thank you Mike for a wonderful article which ha sbeen been most interesting! Thank you also Colin, also for your excellent information on the Noblex 135 models! I am in the UK and wondering if you would not mind please mentioning the size of the silicone “O” ring that you used for your repair of your Noblex? For example diameter and thickness please, or otherwise where I could order the correct size from?

Hi James. I went through a little bit of trial-and-error to get the right size, so let me try to save you some hassle/time. I bought the O-rings from RS Components – a very good supplier, though I think they’ve increased their delivery charges since I bought from them.

When I opened up the camera, I could see the rubber substance around the drive wheel had cracked and crumbled away in places. I carefully scraped away what was left, and fitted not one but three O-rings in its place. I found that to work best.

O-rings are identified by their inside diameter (ID) and outside diameter (OD) and consequently their thickness. I needed two different sizes:

ID 35mm / OD 39mm / 2mm

and

ID 37mm / OD 39mm / 1mm

I installed two of the thinner O-rings first, then one of the thicker O-rings sitting on top of the first two.

Take care opening the Noblex – the film rewind button is not attached and can end up bouncing around your floor. A retaining ring and washer need to be removed to free the drive wheel, and then reinstalled afterwards. After putting everything back together, my Noblex has been given a new lease of life. I couldn’t have been happier with the inexpensive DIY job.

It should be understood that I have a Noblex 135S. I don’t know if the drive wheel is bigger on the medium format models.

Great post, thanks for it. I am a bit late to the party, my Noblex 135U is actually out for repair (there are other things that need to be fixed, too). In Europe there is another repair shop available in the Czech Republic: https://www.photohelp.cz/

While he replies to emails in czech, usage of DeepL helps translating.

One minor thing: Noblex annouced this camera with 146° angle of view, you write 136°. To my knowledge it is the 135mm panorama camera with the widest angle of view.