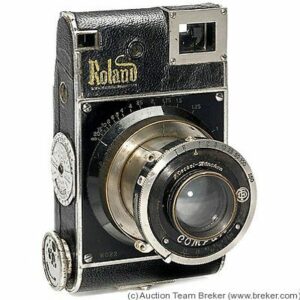

This is a Roland Kleinbild-Kamera, a solid bodied medium format rangefinder camera made by Plasmat GmbH in Berlin, Germany starting in 1934. The Roland shoots sixteen 4.5cm x 6cm images on 120 format roll film. It was a very ambitious, but low produced camera that has a number of features that were ahead of its time such as a combined image conicident image rangefinder in a single, a feature that would not be common for at least a decade after its release. It is also one of very few medium format cameras to have a six-element Plasmat lens, a type of lens more commonly found on large format cameras. In addition to the lens, the camera is said to have been designed by Dr. Paul Rudolph who was a pioneering lens designer who created lenses like the Carl Zeiss Planar and Tessar. As with all low produced and extremely rare cameras, much of the history of this camera is unknown, as some of the facts stated in this very paragraph are up for debate.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (sixteen 4.5cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 70mm f/2.7 Kleinbild Plasmat Dr. P. Rudolph uncoated 6-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Combined Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Compur Rapid Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/400 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Extinction Meter

Weight: 718 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Roland Kleinbild-Kamera was a camera designed around a specific lens, but has a very good build quality, unique features, an excellent shutter, and an attractive look. Even without the lens, it is a capable camera, but to have the complete package of an interesting prewar German camera with an unusual set of features, plus a lens not often found on any other camera, the Roland is truly a very special (and rare) camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 15.4 | ||||||

History

If you were to compile a list of people who have had the greatest impact on the history and future of photography, the list would be quite long. On that list would be names like Louis Daguerre, George Eastman, August Nagel, Oskar Barnack, Masahiko Fuketa, Edwin Land, and many, many others.

In 1890, the German physicist, Dr. Paul Rudolph created the first ever anastigmat lens while working for Carl Zeiss. Although an unnamed lens at the time, Rudolph’s new 4 element lens would later earn the name the Zeiss Protar. The term anastigmat refers to a lens that corrects for the three most common optical aberrations, spherical aberration, coma, and astigmatism. Anastigmat lenses would soon become the norm for photographic lens design and would be prominently featured in the name of lenses produced for more than half a century.

Beyond the Protar, Rudolph would gain even more fame when in 1895 he created both the six-element Planar and in 1902 the four-element Tessar while working for Carl Zeiss. In 1918 he created the Plasmat while working for Meyer-Optik-Görlitz. Each of these three lens designs have been tweaked and reproduced countless times by optics companies from Germany and countries all around the world with the Tessar credited as the most widely used lens ever.

Of Rudolph’s most famous lenses, the Plasmat is the most relevant to this review as a later variation of the 1918 Plasmat was used in the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera. Originally a medium speed six-element design, the Plasmat was ideal for large format photography. Where the Plasmat stood out from other lenses was in its flexibility. The formula could be adapted to a huge number of sizes and focal lengths. It was suitable for macro work and landscapes. Its formula could also be adapted to cover a wide range of cameras from cinema to large format.

The original 1918 Plasmat was a 6-element in 4-group design with a maximum aperture of around f/4. It was a much improved version of the Goerz Dagor double anastigmat, a very popular lens from the era. Improved from the Dagor, the Plasmat almost completely eliminated spherical aberration and had much improved color reproduction.

In 1922, Rudolph released a version of the Plasmat specifically for 35mm cinema cameras that improved light transmission allowing for a maximum aperture of f/2. In 1926 the formula was tweaked once again to f/1.5 making the Kino-Plasmat the fastest lens of any format, in the world.

By the late 1920s, with the increasing popularity of “miniature” cameras such as the Ernst Leitz Leica and other still photography cameras which used a film based on 35mm “kine” or cinema film, Dr. Rudolph once again sought to update the Plasmat to create a lens ideally suited for the emerging miniature camera market. In 1931, a new lens called the Kleinbild-Plasmat was created with a maximum aperture of f/2.7. The word “Kleinbild” literally translates to “small picture”, which loosely refers to this new segment of miniature film cameras.

Despite the name Kleinbild-Kamera which loosely translates to “miniature camera”, the Roland did not shoot 35mm “kine” film, like the Leica did. Rather, it shot 4.5cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. In the medium format world, this format camera was still considered small and likely deserving of the “miniature” name.

Like many low production cameras, very little is known about the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera, not even the name of the company who produced it. In my research for this article, I found the Roland Kleinbild-Camera credited to Plasmat GmbH, Kleinbild-Plasmat-Gesellschaft, and in 1936, to Rudolph & Co. Kamerabau Berlin. Whether any of all of these names were once used is not clear, further confusing the history of this camera.

Paul Rudolph was clearly a talented lens designer, but there is no evidence he had ever built a camera. According to Jim McKeown’s 2001-02 Guide, credit for the design of the camera goes to a Dr. Winkler in association with Dr. Rudolph, but I could not find any additional supporting evidence of who this Dr. Winkler was, or if he had previous camera design experience.

Whoever Dr. Winkler was, I believe that because the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is a fairly advanced model with features not commonly seen at the time suggests that someone with considerable skill produced it. Most likely this Dr. Winkler worked closely with Paul Rudolph for the specific purpose of getting Rudolph’s new Kleinbild-Plasmat lens into more photographer’s hands.

In addition to questions about its manufacturer, the dates in which it was made are up for debate as well. If you search online for information about this camera, some sites like camera-wiki state it went into production in 1931. Other sites like an archived page from ukcamera.com state it went into production in 1933, and Jim McKeown says 1934. We also do not know if the Kleinbild-Plasmat lens was developed specifically for the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera, or if the camera was produced as a later supplement to the lens to give people a better opportunity to use it, but if the latter is true, it suggests the camera came after the lens.

Normally when trying to track down production dates of common cameras, I search catalogs from the same era or advertisements showing when something might have been offered for sale, but that didn’t work with the Roland because of how uncommon it is.

In the case of the Roland, I agree that McKeown’s date of 1934 is the most accurate for two reasons. The first, is that all Rolands came with either a Compur or Compur-Rapid leaf shutter. Compur shutter serial numbers are well documented and can help in dating when the shutter was made. Since a shutter needs to already exist before it can be installed in a new camera, it stands to reason that a camera cannot be made before its shutter. Of course, sometimes cameras and shutters could be swapped while being serviced, so it is possible to encounter a camera today that has a shutter which is not original to the camera, but this should represent a small number of the total number of cameras out there. Combine that with a rare and low production camera, and it stands to reason that many of these cameras likely were never used to the point where their shutters needed to be replaced.

The example in my collection has a Compur Rapid shutter with a serial number in the 508xxxx range, which puts its production no earlier than 1935. A Google image search of other Roland cameras, many more versions had Compur Rapid shutters than the earlier non-Rapid Compurs. In my research for this article, I have not found any Roland cameras with shutters that have a serial number that would have suggested a date as early as 1931.

The second reason I am going with a 1934 date for the camera is that since I know for sure it was definitely being produced as late as 1935, and the 1931 date comes is when Dr. Paul Rudolph created the 70mm f/2.7 Kleinbild-Plasmat lens, I can conclude that 1934 is a reasonable assumption for when this camera might have first been produced as development of a purpose built camera to use a new lens would have taken additional time. Jim McKeown suggests that the camera remained in production as late as 1937, but it is possible actual production ended sooner and some unsold new stock was still on store shelves for a little bit longer.

If determining the correct name of the company and when exactly the Roland Kleinbild-Kameras were made was difficult, it doesn’t get any easier identifying the actual models as there were several variations of the camera, along with a confusing serial numbering system.

Known variations of the camera exist with either a Compur or Compur-Rapid shutter, some have a flat but wide film advance knob, some with a tall but thin knob, some have an automatic exposure counter, some can only be advanced using red windows, some have an extinction meter in the body, some don’t, and some have silvery-white paint in the “Roland” logo and some don’t (although it is possible all were painted but some had it rubbed off). Serial numbers are either 3 or 4 digits ranging from about 300 to 1900, most starting with the letter “S”, but some with the letter “W”. In addition, minor cosmetic variances exist such as some models have a metal cover over the two exposure windows on the back, and the design of the cover varies slightly.

In his guide, Jim McKeown suggests that there was a Roland Kleinbild-Kamera Model 1 with extinction meter and no automatic exposure counter, and a Model 2 with exposure counter, but no meter. As camera-wiki points out, this is much too simple of a classification as the variety of features is far more complex.

While researching this article, I looked at a large number of photos of the Roland camera using Google Image Search, current and sold eBay auctions, and several other auction sites like Westlicht and Live Auctioneers and found a total of 29 Rolands. I am sure more will come up once this article goes live, so if any new conclusions can be formed from those examples, I will update this article. From what I did find however, I struggled to find any conclusive pattern. Here are some of my observations:

- The lowest serial number I found was W022 and it had a Compur shutter, extinction meter, flat advance knob, white logo, and no automatic exposure counter.

The earliest Roland serial number I found was W022, notice the black shutter plate which appears to be original. Image courtesy, Collectiblend. - The two earliest serial numbers I found, W022 and W141 have no bezel around the rangefinder window, and have some cosmetic differences. W022 has a black shutter plate instead of bare nickel like all others, and does not look repainted in my opinion. W141 has a black painted bezel around the viewfinder window, which does not match any other camera I’ve seen. These paint variations and differences in the rangefinder window bezel suggest early examples.

- I found four other W serial numbers, W328, W402, and W429 all of which were equipped the same as W022 and W141, just with no blank paint and a bezel around the rangefinder window. This suggests that most early models had the same features.

- A sixth W serial number which did not match any of the others was W799 which has a Compur-Rapid shutter, no extinction meter, flat advance knob, black logo, and no automatic exposure counter.

- Models with S serial numbers appear between W429 and W799, suggesting that you cannot assume the all W serials came before the S serials.

- The highest serial number I found was S1870 which had a Compur-Rapid shutter, extinction meter, flat advance knob, white logo, and no automatic exposure counter so it is not correct assume that all later models were equipped differently.

- The Kleinbild-Plasmat lenses have their own serial numbers as well, ranging from a low of 1148 to 2092. In my list of 29 Rolands I found online, I was only able to read the lens serial number on 17 of them. Although lens serial numbers tend to climb as the body serial numbers do, they are not linear. Some higher numbered body serial numbers have lower numbered lens serial numbers and vice versa, suggesting the lenses and bodies were built at different times and assembled later. This means that lens serial numbers are no more an accurate way than body serial numbers to date the camera.

A small number of Rolands have an automatic exposure counter feature on the side. These models are never equipped with the extinction meter. - Models with the extinction meter have an exposure calculator in the same location as the automatic exposure counter, so it would have been impossible to equip the same camera with both features at the same time.

- Of the 29 Rolands I inspected, only 5 had the automatic exposure counter suggesting it was a far less common feature. The serial numbers of these models all began with S and range from S491 to S1857 with no discernable pattern.

- With the exception of W799, all other W serial numbers had the extinction meter, but only 10 out of 23 S serial numbers had it.

- Of the 12 S serial numbers without an extinction meter, 7 S had neither the extinction meter or the exposure counter, the other 5 had the exposure counter.

- The lowest serial number cameras do have Compur shutters, but starting in 1935, Compur shutter and Compur Rapid shutter versions of the camera seem to be produced concurrently. It is not true to assume that just because you have a Compur shutter model, that you automatically have an earlier camera as I’ve seen Compur Rapids as early as S482 and Compurs as late as S1404.

Some Rolands came with a non-Rapid Compur shutter with top 1/250 speed. - Some Rolands have what I believe to be aftermarket modifications, such as S1690 which had a Zeiss Tessar lens in a Compur shutter mounted, and S1361 which has a third, but yellow, exposure window in the door. The opening of this third window is different than the other two, suggesting this was added later, however the reason is not clear as this position would be for reading the 6cm x 6cm exposure numbers on 120 film, something the Roland cannot do.

It is clear to me that you cannot simply break down the Roland into simple “Model 1” and “Model 2” buckets as McKeown suggests. If anything, there should be a third model, for those with neither an exposure counter or extinction meter. In his defense though, the resources I used to come to my conclusions likely weren’t available to him when he wrote his guides.

With what we know now, I feel as though I can come to a couple general conclusions. The first is that the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera was likely produced from about 1934 to 1936, and a total of between 1500-2000 were made. I tend to favor a lower number as there are many examples of old cameras in which serial numbers do not match production numbers as there are almost certainly gaps.

The Roland Kleinbild-Kamera would have been seen as a premium German camera with a state of the art and very high quality lens, excellent build quality, and included several innovative features such as a combined image coupled rangefinder, extinction meter, and automatic exposure counter. In his 2001-02 guide, Jim McKeown suggests the camera originally sold for between $93 and $143. While I found no evidence the Roland was exported to the US, if these prices are correct, it would have put the Roland in the same price range as Voigtländer Prominent 6×9 and Rolleiflex cameras being sold in the 1935 Central Camera catalog.

One final conclusion which I’ve come to is that due to the pure randomness in combinations of shutters, extinction meters, and automatic exposure counter suggests perhaps that the camera was made to order. There is no evidence the camera was sold outside of Germany, so it is possible that orders for the camera went straight to the factory and each model was built to order with whatever features the customer wanted (and could afford). If the camera’s features could be ordered a la carte, the automatic exposure counter feature was likely the most expensive as it is also the least common. For these reasons, I respectfully disagree with McKeown’s “Model 1” and “Model 2” designation, as it was likely formed based off incomplete information.

Dr. Paul Rudolph would pass away in March 1935 at the age of 76. His death would have occured only slightly after the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera went on sale, but with enough time for him to see his Plasmat lens be successful.

After his death and after the end of production for the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera, no new cameras were credited to Plasmat GmbH or either of the two other names the camera was credited to. It is possible that the intent of the company was solely to produce a camera that featured Rudolph’s Plasmat lens, or poor timing with the looming second world war put an end to any future development.

Although seen as a successful lens formula, the era of the Plasmat was short lived, at least compared to other Rudolph designs like the Tessar and Planar, variations of which are still produced today. As best as I can tell, Meyer-Optik-Görlitz did not continue to produce any variation of the Plasmat after the war, however variations of the lens were picked up by other German and Japanese lens makers. A huge number of lenses that came later would follow the Plasmat’s basic 6-element, double anastigmat formula, so you could say that it inspired future development of cinema, miniature, and large format lenses.

Today, Plasmat lenses enjoy a popular choice for large format enthusiasts who like to use classic early 20th century lenses. The Plasmat’s good, but not perfect performance is ideal for people looking to achieve a vintage look in their photography, something which more technically perfect lenses cannot do.

The Roland Kleinbild-Kamera however, is a mystery to all but the most deep pocketed collectors as a combination of the camera’s rarity and history make for quite a high price tag on the used market. They are not the rarest camera, as at any given time, a few are always for sale on eBay and other online marketplaces, but finding one in any condition for under $1000 is difficult, with mint condition examples having prices three to four times higher. This is a shame though, as the camera’s good looks, unique feature set, excellent lens, and historical significance make it something that should be enjoyed by as many people as possible.

My Thoughts

The Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is sort of two different cameras at once. On one hand, it is a pre-war German roll film rangefinder with a good lens and shutter. There are other cameras with a similar spec sheet. But beyond the basic list of features, the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is unlike any other. For starters, it is the only camera ever made purpose built for Dr. Paul Rudolph’s Plasmat lens. In fact, in my entire collection, this is the only Plasmat I own. In addition to its unique lens, the camera has a unique appearance. Resembling one of those vertically traveling half-frame cameras like the Yashica Rapide or Taron Chic, except larger and using roll film, the camera is unlike any other. Finally, with a very unique combined image rangefinder in which the beamsplitter sorta “floats” in the middle of the viewable image on top of a post, it works like no other camera I’ve used.

At its simplest, the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is a prewar German camera with typically high German prewar build quality and a German prewar nickel and leather appearance. The camera is very attractive with its large swaths of nickel plating, gothic script logo, and pronounced metal bezels and bits all over the body. Weighing just over 700 grams, the camera isn’t exceedingly heavy, but for a compact body, the camera feels dense. The Compur-Rapid shutter and Plasmat lens are collapsible, and when extending the lens, the barrel moves with a firm but smooth motion, and firmly locks into place with a quick twist of the wrist offering confidence that the lens won’t automatically retract while shooting. There might be some ambiguity as to who actually built the non-lens parts of the camera, but whoever did it, did a terrific job, easily on par with the best that Zeiss-Ikon or Voigtländer were doing at the same time.

Holding the camera upright to where the viewfinder window is up, the top of the camera has little going on. Apart from two metal strap loops on either side of the camera, there is nothing to see. Even looking down upon the shutter from this angle and you see no markings for focus, shutter speeds, or f/stops. The only thing present is the self-timer catch for the shutter, which requires you to push toward the body of the camera while cocking the shutter.

Opposite the top (I hesitate to call any side of this camera the bottom), and you’ll see a sliding door latch for opening the film compartment. A stylized arrow indicates the direction you must slide a button in order to open the door. Once again there’s nothing to see on the shutter other than the bottom part of the aperture selector.

Of the two sides of the camera, one is completely empty and the other has the film advance knob, a 3/8″ tripod socket and the rather confusing calculator for the extinction meter that some Rolands came with. The extinction meter is not working on this camera, so I made no attempt to figure out how to use this calculator, but even if I had, it is written entirely in German, so that wouldn’t have helped either. Some versions of the Roland have an automatic exposure counter which would be in the same location as the exposure calculator. Since mine doesn’t have it, I can’t speak to how it works.

Around back, once again with the viewfinder up, there is the viewfinder window in the upper left corner. Compared to other 1930s rangefinder cameras, the eyepiece is impressively large, much larger than that of cameras like the Kodak Retina or even the Zeiss-Ikon Super Ikonta. Next to the eyepiece is the opening for the extinction meter which on mine doesn’t work. Peering through the round hole is complete darkness.

Lower down the body, on the film door are two red windows for viewing the exposure numbers printed on backing paper for 120 film. Since 120 film did not commonly have printed numbers for 4.5cm x 6cm images, the 6cm x 9cm images must be used twice. Each of the 8 exposure numbers must be used twice, once in each window. The first exposure is made with the number 1 in the first window. Then after making your exposure, wind the film until the number 1 is in the second window and then make your second exposure. Advance the film so the number 2 is in the first window and make your third exposure, advance again until the number 2 is in the second window for your fourth, and so on. Continue doing this until the number 8 is in the second window, at which point you’ve made your 16th exposure. Some later versions of the Roland have a sliding door to protect the red windows from extra light, but this copy did not have that feature.

When opening the film door, the hinge is located just below the viewfinder and extinction meter openings, so the back swings open from that point. If you are holding the camera in shooting orientation, the door swings up, so it is easier to load the camera with it facing a table or laying on its side. The film compartment is a rather ordinary looking 120 roll film compartment with room for two film spools. The take up side is the one below the film advance knob, and the supply side is the other. When loading film, there are no indexes for the START mark, simply attach enough of the paper leader to the take up spool so that it is secure and close the door. After closing the door, look through the two red windows, and wind the film advance knob until you see the number ‘1’ in the red window nearest the door hinge, at which point you are ready to shoot.

Up front the Roland has a rim set Compur-Rapid shutter. the shutter is collapsible and must be extended before shooting otherwise you’ll have grotesquely out of focus images. There is no interlock to prevent you from firing the shutter unless it is extended. To extend it, simply pull the entire shutter and lens from the body. On one part of the metal barrel is a line with an arrow. This line and arrow indicate how far to pull it out and in what direction to twist it so that it will lock into position. You should know that the shutter can be locked into position in multiple orientations. The standard “up” orientation should have the arrow facing the side of the camera with the viewfinder, but it can be done with it facing other directions. None of these other directions are wrong, it just makes it harder to read the settings.

Shutter speeds from 1 second to 1/500 plus T and B are selected by the metal ring around the perimeter. A cocking lever near the “D” in “Deckel” cocks the shutter for all of the instantaneous speeds. Like early Compur Rapid shutters, both T and B can be fired without first cocking the shutter. In fact, if the shutter is cocked, you cannot change the speed ring to either the T or B settings, the shutter must be uncocked to select those speeds. The shutter release sticks out just like the cocking lever, but is near the bottom left corner of the shutter. The shutter has an unlabeled self timer which is a round button near the very top of the shutter. The way it works is that when cocking the shutter, if you first push this button in the direction of the back of the shutter while moving the cocking lever, the lever will travel farther, into a self timer position. When firing the shutter release, a mechanical governor will delay the release of the shutter by about 8-10 seconds. Like any leaf shutter, it is advised you do not try to use the self-timer unless you are sure it is in proper working order as it can jam the entire shutter.

A socket for a shutter release cable is on the side in between the cocking and shutter release levers, and on the bottom of the shutter is a little arm for controlling the diaphragm. F/stops from f/2.7 to f/18 can be chosen. Finally, the entire shutter is mounted to a focusing helix in the main body of the camera. Focus distances are engraved from just under 1 meter to infinity. There is no depth of field scale on the camera.

The viewfinder on the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is large and bright, especially for a camera from the mid 1930s. It is truly unique on the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera. Inside is a combined image coupled rangefinder, but it is not of the coincident image type where in you can see through the rangefinder patch to line up two images at the same time. The Roland uses a solid mirror rather than a beamsplitter which is mounted to a metal pole sticking up from the bottom of the viewfinder. Strangely, the location of the rangefinder and its pole is off center a bit. The pole and a frame around the rangefinder do block a small bit of the light coming through the viewfinder, so when lining up the image from the rangefinder with the main viewfinder window, there is some light blockage, but in my example, it was still easy enough to get properly in focus images.

The style of rangefinder in this camera is a bit rudimentary, it is important to remember that in 1934 when this camera first went on sale, most rangefinders were of the split image type, like an Argus C or AGFA Karat. One added bonus to the system on the Roland is that because a beamsplitter is not in use, both the main part of the viewfinder and the rangefinder mirror are very bright, and have none of the haze or dimness often associated with beamsplitters.

Earlier in this review, I mentioned that the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera was unlike any other camera, and that is true. No one else designed a camera like the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera because very quickly after it was made, people found better ways to build cameras. That’s not necessarily a bad thing though. The Roland is a very attractive, oddly shaped, and strange working camera with some features not found anywhere else. As an excuse to build a camera around the Plasmat lens, it succeeded, but as a camera you’re likely going to take with you on a family trip to the zoo, not so much.

Still, when collecting and shooting old cameras, no one gets too excited about another run of the mill German folding camera or a mid 1950s Japanese rangefinder, it is the odd ducks like the Roland that turn heads, and boy does this camera turn heads. It is one thing to play with the camera while sitting at a desk and pretending to use it, but it is another to load in some film and take it out, so that’s what I did!

My Results

The great thing about leaf shutters, especially Compur leaf shutters, is that it is usually pretty obvious when they’re working and when they aren’t. In the case of the Roland, a quick hearing test of each of the shutter’s 9 speeds produced audibly different sounds. Sure, my ears don’t have the precision to hear whether 1/400 is really 1/400 and not 1/340, or 1/100 isn’t 1/78, but it was close enough that I felt confident enough for a first test with a film that I don’t have a lot of. Back in 2022, I came across a lot of expired film and in it was a bunch of 10 year expired Arista.Edu 400 roll film. Having a surplus of a low value film, I figured would be a good first test. If the shutter died or if the camera was riddled with light leaks, it wouldn’t be a huge loss, but if it performed well, the Arista.Edu film should produce good enough images.

Normally I start this section with my comments on the lens, but for the Roland, I’ll start with the rangefinder. As one of the first combined image rangefinder viewfinders, the Roland isn’t like most other cameras. Instead of using a split image or some kind of beamsplitter, the rangefinder is an optical block of glass sitting atop a pole, right smack in the middle of the viewfinder. While it works like most rangefinders, it is unique in that there is an opaque border around the reflected image that separates it from the main viewfinder image. For the unfamiliar, this is a little distracting as there is a break before the two images, and unlike coincident images where part of the light reflects off and passes through the beamsplitter, you cannot see the two images at once.

Despite these differences, the rangefinder on this 90 year old camera was calibrated perfectly. The entire roll of images in the gallery above was in focus, even the mirror selfie in which I focused on the Roland logo, and not the lens. Of all the prewar cameras that I have ever shot, not only is this the earliest rangefinder, but it is the first where I nailed focus on every image, the first time I ever shot it!

Then of course the lens. The Roland in some ways, is like cameras such as the Hasselblad SWC and the Zeiss-Ikon Hologon Ultrawide in which the camera was built specifically around a single lens. Unlike those other two cameras in which the lenses are unique ultra wide angles, the 70mm f/2.7 Kleinbild Plasmat is of a normal focal length. On paper, there really isn’t anything special about this lens, other than it was originally developed for purposes other than medium format roll film. We have the benefit of hindsight today to know that the Plasmat lineage wouldn’t last much longer than this camera, but for Dr. Rudolph, and Hugo Meyer whom he worked for, this was a lens to be proud of, and worthy of having a camera built around it.

And they had every right to be proud. The image quality in the gallery above is outstanding. I’d say as good as any Schneider Xenon, Voigtländer Ultron, or Zeiss Sonnar I’ve shot. Sharpness and contrast are excellent corner to corner. I did notice a bit of vignetting in the extreme corners in some images, but apart from that, the lenses had no obvious optical anomalies associated with lesser lenses. I’ve heard some comments online that the reason the Plasmat was not more successful was that it was known to be soft and have poor bokeh. That may be true in a lab or for people who look for those things, but as a general purpose lens, I was very impressed with the image quality in my test photos.

If you’re one of those people who look at every lens and wonder what it would look like when shot digitally, you’re in luck as while researching this article, I found a blog from an ambitious Japanese enthusiast who removed this lens and and mounted it to a Sony a7RII, and also a Leica M240. I suspect whoever did the modification used some type of bellows system or an external helix as many of the images are much closer than the lens normally goes, but the image quality is outstanding.

Despite not being made by a top tier German camera maker, the Roland Kleinbild-Kamera has excellent build quality, a large viewfinder, and good ergonomics. I appreciated the vertically traveling film direction, which allowed me to use the viewfinder in a landscape orientation as opposed to many other “Semi” or “Duo” 4.5cm x 6cm cameras in which the default orientation is portrait.

In fact, the camera works so well in landscape orientation, that it is actually inconvenient to use when turned sideways. The location the shutter mounted shutter release becomes awkward to reach, and the viewfinder, instead of being in the upper left corner, goes to the bottom left corner when rotated 90 degrees. I didn’t shoot too many portrait orientation images for this reason.

The extinction meter on this example didn’t work, so I didn’t get a chance to use it, and of course this one lacks the automatic frame counter, so I just relied on the two red windows and Sunny 16, and as you can see, the expired 400 speed film returned a roll of excellent exposures.

The only real con to the camera was that due to its odd shape and front heavy lens and shutter, it would have benefitted from a kickstand or some kind of foot so that you could set it flat on a table. Even when laid on its side, the camera always wants to tilt forward on its lens. This makes shooting long exposures on a flat surface difficult as does your ability to display it on a shelf.

The Roland Kleinbild-Kamera is an extremely uncommon camera and one in which very few have probably been used in the last several decades. This is certainly not a camera your average collector has access to, and if they do, likely never gets used. I was very pleased at not only the condition and operation, but also the ergonomics and performance of the lens. This was a very fun camera to shoot and one I’ll likely take out again.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Roland

https://kirksuniverse.com/2016/11/06/fun-with-an-80-year-old-camera/

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C216.html#C216

https://flashbackcamera.jp/brand/other/body/021032-other-roland-kleinbild-plasmat-70mm-f27/?sl=en

https://web.archive.org/web/20160312054631/http://www.hayatacamera.co.jp/article/photo200412.html (archived)

https://web.archive.org/web/20160414173046/http://www.ukcamera.com/classic_cameras/plasmat1.htm (archived)

Have you seen this one, from a German ad page? No idea how this adds up in your research about the model.

Steep price indeed, but pretty complete kit. https://www.kleinanzeigen.de/s-anzeige/roland-plasmat-mittelformat-film-kamera-compur-2-7-70-1930er-/2631783652-245-617

“the Plasmat lineage wouldn’t last much longer than this camera”

While this may be true for lenses called “Plasmat”, it certainly was not the end of this kind of lens. All high quality large format standard lenses beside the Tessar are based off the Plasmat lens formula – Symmar, Sironar and so on, they’re all plasmats, and I think some of the 8 element large format wide angles may also be derived from that design.

Intensive investigation!

You can be glad that the rangefinder works correctly: it’s annoying to fix in position the mirror. On the one hand there is a complex opposite differential thread, on the other hand there is no fine adjustment of the mirror!?

The numbers of my Roland are as follows:

Body: W429

Compur: 3048012

Lens: 1393

Mike, for a guy who claims not to know much about lenses and their history, this is a fine and detailed article about … LENSES! Thank you.