This is a Miranda Automex a 35mm SLR camera made by Miranda Camera K.K. in Japan between the years 1960 and 1962. The Automex was Miranda’s first metered cameras and also the first in what was then a new body design which had a single shutter speed dial for fast and slow speeds and used different prisms compared to earlier models. The Miranda Automex used a large selenium meter in the front of the prism to control a match needle in the viewfinder. The use of the prefix “auto” in the name refers to the camera’s support for a new type of external lens coupling allowing open aperture metering. This style of lens coupling would continue into the company’s Sensorex range. The Automex was a moderate success for Miranda, spawning two follow up models, the Automex II and III in 1962 and 1964 respectively.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/1.9 Miranda coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Miranda Bayonet w/ External Aperture Coupling

Focus: 17 inches / 0.45 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ viewfinder match needle

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Clip On Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 960 grams, 766 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/miranda_pdf/miranda_automex.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Miranda Automex was an innovative and well featured SLR in the era which it came out. Although not a pioneer of any new technologies, it did combine a good amount of modern capabilities into an affordable camera. Early Mirandas like this have a much better build quality than later ones, and with the excellent Miranda lenses available at the time, this is a very capable camera that makes it a capable shooter today. The biggest con about this camera however is its dark viewfinder and that despite a good feature set, still isn’t much better than other options of the same era. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | None | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.6 | ||||||

History

Miranda cameras are one of the most interesting brands for me. This Japanese company made some of the most attractive and capable cameras of the era. Where most Japanese companies created cameras in which function took precedence over form, Miranda leaned towards a more German style in which the looks of the camera were as good as their operation.

Although lenses could be adapted from one system to another since the very first screw mount rangefinders were made, Miranda was the first company who took a serious approach to adapting lenses with their dual lens mount in which an external claw bayonet mount surrounded an internal 44mm screw mount. This, in addition to having the shortest flange focal distance of any currently available 35mm SLR camera, meant that lenses from every other SLR made at the time could easily be adapted, while preserving infinity focus.

The company who made the Miranda SLR was originally called Orion Seiki Sangyō Y.K. or Orion Precision Products Industries Co., Ltd. in English, and got started as a maker of photographic accessories. Some of the company’s most successful products were a series of reflex finders and bellows attachments for the Leica screw mount. With a background in making accessories, Orion was well suited to producing a huge variety of accessories and adapters for their new SLR.

Orion’s first prototype SLR was announced in 1954, which had it gone on sale at that time, would have made it only the second Japanese SLR. Realizing that not only were the Germans still “kings” of the camera making world, and that the Single Lens Reflex design was still a niche product, Orion correctly assumed that someone would be more willing to consider a little known Japanese model, if it meant that all their existing lenses could be used with it. As a result, every single Miranda SLR ever since that original Orion prototype, all the way to the company’s last camera, the Miranda dx-3 from 1974, shared this same mount.

Miranda cameras also had another trick up their sleeve, which was their value. All Mirandas were sold at a price undercutting the competition, yet the cameras were well equipped. Every model except for the very last one had a removable viewfinder which meant that both prism and waist level finders could be used. As Orion was not a lens maker, rather than attempt (and possibly fail) at coming up with their own designs, they smartly tapped companies like Zunow and Soligor to make lenses in their mounts. The optical quality of these early lenses were easily on par with the best Japanese lens makers of the 1950s.

Unlike other companies who would release a whole new model every couple of years, Miranda cameras were constantly evolving with new models being released, sometimes multiple times a year, with new features. The first Miranda camera went on sale in 1955, and by 1959 the company had ten different models, the most recent ones supporting features like an instant return mirror, lever film advance, and split image focus aides.

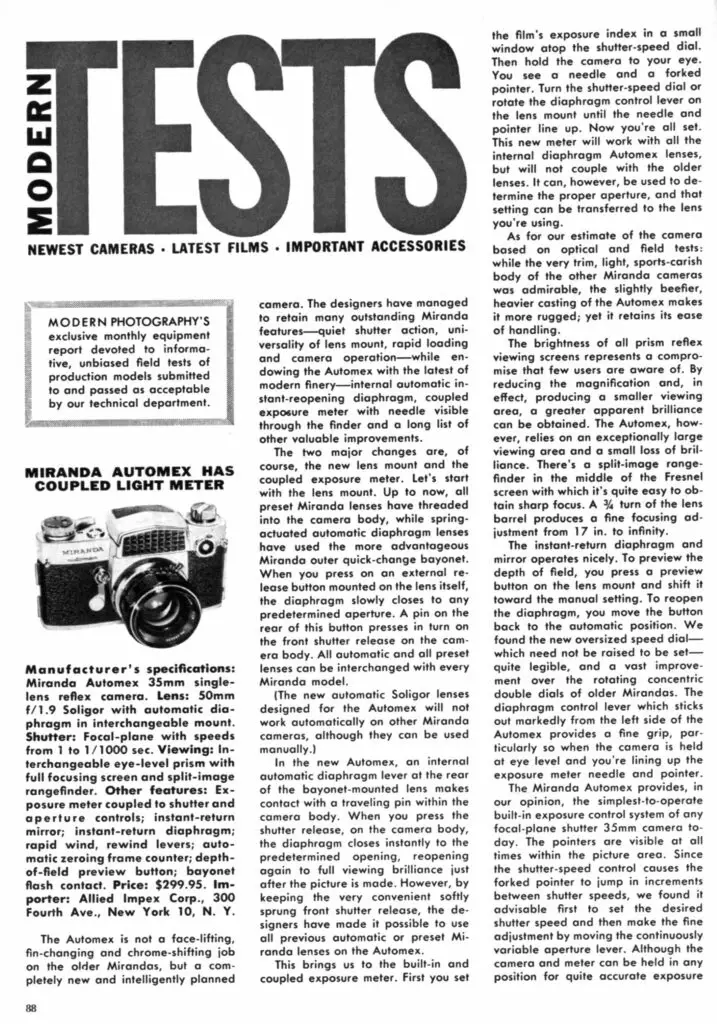

In 1960, Miranda would debut a new series of camera called the Automex with a huge number of new features. The Automex body was completely redesigned from earlier models with a more modern shape and softer curves. It was the first Miranda camera with a self-timer, automatic resetting exposure counter, a shutter ready indicator, and a single piece non-rotating shutter speed dial where all speeds are together. The shutter was designed to be quieter, with built in dampeners to reduce the sound of it firing. The camera also had a motor drive coupling for a motor drive which was never made. While each of these features went a long way towards modernizing the Miranda, the most significant new feature was the coupled selenium exposure meter mounted in front of the pentaprism which gave the camera open aperture match needle metering.

Any time you add open aperture metering to an interchangeable lens SLR, there needs to be a connection between the lens and camera body so that the meter knows what f/stop the lens will be stopped down to at the moment of exposure. In order to accomplish this, Miranda took an approach similar to that of Nippon Kogaku with the Nikon Photomic cameras and they added an external coupling to the lenses, making a physical link back to the body. While adding an external protrusion to the lenses to make this feature work may not have been ideal, it meant that the company didn’t have to come up with a new mount and all previous lenses would still work on the camera with stop down metering. Six new lenses were released with this external coupling, ranging in length from 28mm to 135mm. All other Miranda lenses would still work, just without the meter coupling.

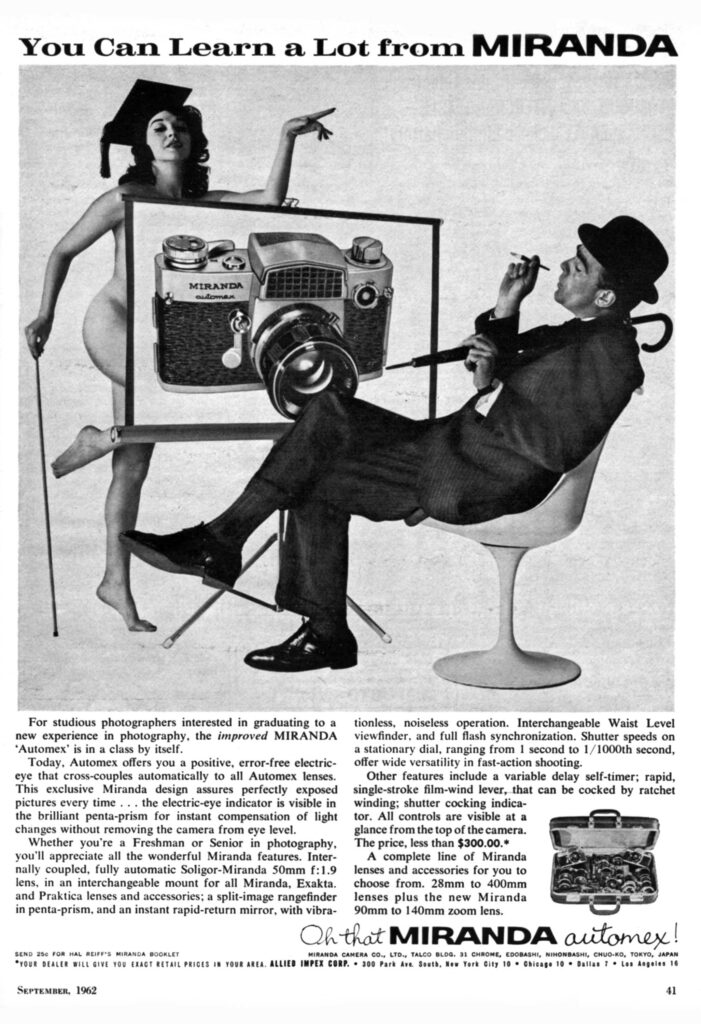

Since you can’t have a Miranda camera without Miranda ads, the Miranda Automex was often paired with the Miranda D which also came out the same year, in ads with risque photos of “Nancy”, a scantily clad model featured in most of the company’s marketing material at the time.

The Miranda Automex carried a retail price of $299.95 with a Soligor 50mm f/1.9 lens. Comparatively, the non metered Miranda D came with a Soligor 50mm f/2.8 or 50mm f/1.9 lens for a much lower price of $119.95 and $159.95 respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to around $3100, $1250, and $1650 today, quite a hefty price to pay, but still cheaper than the competition!

The Miranda Automex was given a short review in the July 1961 issue of Modern Photography where they commended the camera’s long feature set and excellent selection of lenses. It says the Miranda Soligor lenses represent one of the best lens series available for any 35mm camera. Other positive comments are given to the camera’s handling and rugged design, and long list of accessories. The article mentions that a 58mm f/1.5 lens was planned, but I have never seen one, so I am uncertain if it was ever developed. Strangely, this article makes no mention of the motor drive coupling.

In 1963, the Automex was updated with a new model called the Automex II. The two cameras are very similar, with the only changes being that the new model expanded the available film speeds to ASA 10 to 1600, instead of the original model’s rather limited range of ASA 6 to 400. Another change was made to the flash mount, which on the original model had some kind of proprietary bayonet mount with a PC Flash adapter. The original bayonet mount was removed and the PC Flash port was the only option. A mid model change to the Automex was a redesign of the screen in front of the meter from one with a bubbled texture to a flat texture was standard on the Automex II. The only other difference is the removal of the motor drive coupling on the bottom of the camera, which was never used.

In 1963, the Automex was updated with a new model called the Automex II. The two cameras are very similar, with the only changes being that the new model expanded the available film speeds to ASA 10 to 1600, instead of the original model’s rather limited range of ASA 6 to 400. Another change was made to the flash mount, which on the original model had some kind of proprietary bayonet mount with a PC Flash adapter. The original bayonet mount was removed and the PC Flash port was the only option. A mid model change to the Automex was a redesign of the screen in front of the meter from one with a bubbled texture to a flat texture was standard on the Automex II. The only other difference is the removal of the motor drive coupling on the bottom of the camera, which was never used.

A third and final Automex, simply called the Automex III would be released in 1965 which replaced the large selenium meter with a round CdS meter which is located where the flash sync port was on the previous models. A smaller PC port was moved above and to the right of the CdS meter and a battery compartment for the meter was added to the rear of the camera. In place of the selenium meter on the front of the prism was a decorative plate with the letters CdS stamped into it. The film speed dial was changed once again. The fastest speed was still ASA 1600, but the minimum speed was increased to ASA 25.

The Automex III would only be produced for a short period of time as the Miranda Sensorex would be released the following year, replacing the Automex series with the most significant new feature being through the lens metering.

Miranda would enjoy good success throughout the 1960s as a value added alternative to other Japanese brands. For just a few dollars less, you could buy a Miranda camera with the same, or sometimes more features than competing models by other companies. This approach, combined with distribution to western countries like the United States kept the company afloat for a lot longer than many smaller Japanese camera makers. Unfortunately, mismanagement both by Miranda and its primary distributor, Allied Impex Corporation caused quality control to suffer and Miranda’s reputation in the marketplace to plummet. By the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s, Miranda cameras were no longer seen as viable options for serious photographers and were relegated to discount camera status. Poor quality control and the company’s inability to adapt to the increasing using of electronics in cameras led to the company’s demise and by 1975, Miranda would go out of business.

Today, Miranda cameras are generally pretty sought after by collectors. The earlier models like the Automex were well built and quite attractive. With a feature set not common among mid level camera makers, when found in working condition, Miranda SLRs are still capable shooters. That the company used its own lens mount not used by anyone else, Miranda lenses can be picked up for very little money on the used market and adapted to digital cameras with good results. Whether you are looking for a well made full sized Japanese SLR to shoot, or just display on a shelf, these cameras are worth adding to your collection.

My Thoughts

It would not be unreasonable for someone to judge a Miranda camera solely on its reputation. Whether you remember Miranda back when these cameras were originally being sold, of ir you’ve only learned about them once they became collector’s items, you’ve almost certainly heard something negative about their reputation.

Certainly, there are good reasons to think that Miranda cameras were less than say, Nikon, Canon, or most other Japanese and German cameras. There is a reason the company went out of business after all. Plus, long time readers of this very site will remember my early attempts at shooting Miranda cameras consistently didn’t go to plan.

But to judge an entire brand of camera based on a few bad apples would be like judging the Ford Motor Company based on the Edsel or Apple on the Newton. The reality is, many Miranda cameras, especially the early ones are quite capable cameras with competitive features, good build quality, and capable lenses. I don’t have any definitive proof of this, but based on my limited observations, it seems as though Miranda’s quality control really started to nose dive around 1966, so models built before that generally age well, and ones after that don’t. The Miranda Automex is much earlier than that, and should be in the range of “the good ones”.

Whether this is your first Miranda or your 10th, the Miranda Automex feels like a robust full bodied Japanese camera. Its weight is comparable to that of an Nikon F or early Minolta SR-series SLR. The chrome plating is well done, body covering is not peeling, fit and finish is a good as anything else out there, and all the various knobs and dials move as expected without excessive tightness or feeling loose.

The Miranda Automex was the first model in Miranda’s new design, with a new prism, single shutter speed dial with both high and slow speeds, automatic frame counter and redesigned film advance lever. On the left is the rewind knob with fold out handle, and beneath it is a flash sync dial which allows you to choose between FP and X.

Dominating the center of the top plate is the large removable prism. Miranda was the first Japanese camera maker to release an SLR with interchangeable viewfinders, a feature followed by Nippon Kogaku, Tokyo Kogaku, Canon, and others. The Miranda’s viewfinder uses a rear sliding mount in which a button on the back of the camera is pressed and the prism slides backwards along a groove. I prefer this design much more than cameras like the Nikon F-series in which the prism lifts straight up. In addition to the standard pentaprism, a waist level finder and two different precision magnifying viewfinders were also made for the camera. Although the Automex’s viewfinders are replaceable, the focus screens are not.

To the right of the prism is the automatic resetting exposure counter, a small shutter ready indicator, and the combined film advance lever, film speed, and shutter speed dial. For the first time ever on a Miranda SLR, all shutter speeds from 1 – 1/1000 seconds plus Bulb are on a single, non-rotating dial. Each shutter speed is marked with a strong click stop preventing accidental speed changes. The shutter speed dial cannot be rotated between the B and 1000 setting, you must go the complete opposite direction. To change film speeds for the exposure meter, lift up on the speed dial and rotating it, while looking at the small window where ASA speed numbers from 6 to 400 are displayed. The film advance lever has a tight spring and a high gearing which requires a shorter than usual motion to fully advance the film. The entire movement is less than 180 degrees and must be completed in a single motion.

The base of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, rewind release button and what looks like a motor drive coupling. The presence of this coupling is interesting because as far as I know, no such motor drive was ever made. It is not mentioned in the Automex’s user manual, nor any of the advertising for the camera, and the feature was removed on both the Automex II and III models that followed it. That this coupling exists on the original Automex suggests that Miranda had even more ambitious plans for the camera that were never realized.

Both sides of the camera have forward angled metal strap lugs which help balance the camera with a heavy lens mounted. The left side has a sliding door latch for opening the rear film compartment. From this side you can also see the coupled meter and aperture arm which I’ll explain later.

Around back there is the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, which is internally threaded for a variety of viewfinder accessories such as eyecups, diopters, and right angle viewfinders. To the left of the eyepiece is the release button for removing the prism. Push this button to the left while pulling back on the prism and it will slide off. To the right of the eyepiece is the camera’s serial number and MIRANDA CAMERA, Japan.

The right hinged film door swings open to reveal a pretty standard film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a non-removable metal take up spool. A single slit in the spool is where you attach the leader to. The film spool rotates clockwise which is opposite of how the film is wound inside the cassette. Having the film wind on the spool in this direction was done as it was thought to improve film flatness. Polished rails above and below the film gate and a dimpled texture on the metal pressure plate help reduce friction as film transports through the camera. The Automex uses a velvet door hinge seal and fabric seals in the door channels, which on this example were not degraded and did not need to be replaced.

Looking down upon the Miranda 50mm f/1.9 lens made for the Automex, the aperture ring is closest to the body and is partially obscured by the selenium meter on the front of the prism. Choosing f/stops is done by moving the coupling arm which is located near the bottom of the lens by your left hand. The aperture ring moves freely without click stops allowing for infinite variability of the match needle. Alternatively, a second aperture scale is on the Automex body next to the aperture coupling arm. A thick metal focus ring takes up most of the lens barrel and has distance markings from 17 inches or 0.45 meters to infinity engraved. A depth of field scale is in between the focus and aperture rings and has a red R index for infrared film.

Up front, the Miranda Sensorex has the familiar Miranda dual mount. All Miranda cameras have both a unique 4 claw bayonet mount with an internal 44mm screw mount. The screw mount was used for some early Miranda lenses, but usually adapters which allowed the Miranda to mount lenses for other systems. A tab on the left side of the lens must be pressed to release the bayonet mount. An annoying design quirk of all Miranda bayonet mount lenses is that the 4 claws of the bayonet are evenly spaced, which means that it is possible to mount the lens upside down or 90 degrees off. For this reason, it is critical to line up the orange arrow on the body with an orange dot on the lens before mounting the lens. If you do it incorrectly, the lens will not be lined up on the body correctly.

To the left of the lens mount is the mechanical self-timer lever which adds an approximate 8 second delay before firing the shutter. Above the lever is the threaded shutter release button. The front location of the Miranda’s shutter release is one of my favorite features of this camera as it allows you to hold the camera more securely while pressing the shutter release. When pressing a front shutter release, the motion is inward toward your face, rather than downward like with a top plate shutter release.

Above and to the right of the lens mount is the flash sync port. On the original Automex, a bayonet flash port is built into the body, which was never used on any flashes made for the camera. Instead, a regular PC flash sync adapter is attached. Like the motor drive coupling on the bottom of the camera, this was likely designed for a future flash accessory which was never built.

Whether you have the pentaprism viewfinder or the waist level finder attached, the viewing screen is the same. The Automex has a split image focus aide in the center with a ground glass collar round it. Beyond the ground glass collar is a Fresnel pattern which improves brightness across the focus screen, but doesn’t completely eliminate vignetting in the corners. While I wouldn’t describe the Miranda’s viewfinder as dim, it is certainly not as bright as other SLR viewfinders over the years. It is acceptable for a camera from 1960, but you’ll still struggle a bit in dim light, even with the lens diaphragm wide open.

The Miranda Automex has an automatic diaphragm meaning the lens is always wide open until the moment of exposure, or by pressing a depth of field preview button on the lens itself. The external coupling arm that was added for the Automex series is coupled to the diaphragm and the match needle visible in the viewfinder. A needle on the right side of the screen is coupled to the film and shutter speed dial and moves freely depending on how much light is hitting the selenium meter. A needle with a C-shaped tip is connected to the aperture arm, and must be moved so that the meter needle is in between the C needle. With the needle in the middle of the C needle, proper exposure is obtained. You can move the C needle with both the aperture lever and shutter speed dial, however since shutter speeds have full stops, the C needle moves in large jumps. For this reason, the best way to meter the camera is to first set a shutter speed that gets the match needles close, but then make fine adjustments to the aperture. This style of match needle works similarly to those found on other cameras, but is just a different design. In use, I find the system on the Automex to be just as simple to use as stationary ones found on other cameras like the Nikon F Photomic.

It doesn’t take long after handling the Automex to see that this was a well thought out camera with a large number of improvements over earlier models. In fact, I would argue, that for a very brief time, the Miranda Automex was the most advanced 35mm SLR available. With a selenium meter, accurate match needle metering, interchangeable viewfinders, a dual lens mount, support for advanced flashes and a motor drive (both of which were never developed), and a good range of lenses, the Miranda Automex gave you a lot of camera for the money.

Certainly, the Automex looks pretty good on paper, but what is it like to shoot? Keep reading…

My Results

When I first started reviewing cameras on this site, a recurring theme I had whenever I tried to shoot a Miranda camera was how often I had problems with them. Failure after failure after failure resulted in completely unusable rolls with out of focus or grotesquely underexposed images. I even dropped one camera in the toilet! As the years went by, my luck changed, and I started to have better luck with models like the Miranda A, D, and the Sensorex.

So while I felt the curse was over, when I had the chance to shoot this Miranda Automex, I wanted to give someone else a try who had never so much as seen a Miranda in his life. Enter Anthony Rue, owner of Volta Coffee in Gainesville, Florida and one of my co-hosts on the Camerosity Podcast. I sent off the Automex to him and he agreed to put in a few rolls of film and see what he got.

In total, Anthony shot four different rolls of fim, totaling over 100 images. The gallery below shows a sampling of some of his shots. The color film is Fuji Superia 400, and the black and white is Kosmo Mono 100.

Although I did shoot a roll of film through the Automex, Anthony’s results are leaps and bounds better than the results I got, so I’m only sharing his. This also brings into question my own abilities as a photographer. Maybe I should focus just on the usability and history sections of future reviews and trust the actual use of these cameras to people who are far more talented than I!

Looking at the results, I can see that the Miranda branded lens on the Automex is on par with equally excellent images I’ve gotten on other Soligor branded lenses shot on other Mirandas. In fact, I am pretty certain that this lens is an actual Soligor design, simply branded as a Miranda as I don’t believe Miranda ever made their own lenses. The 5cm f/1.9 lens does an excellent job of delivering predictably sharp results when stopped down, but wide open, has a soft glow to them, adding a wonderful vintage look. I have noticed softness wide open on other Miranda/Soligor lenses before, and really love the look.

I don’t know what apertures Anthony used in his outdoor shots, but I suspect they were in the f/8 to f/16 range which is what I would have used, and I found that sharpness and contrast was excellent corner to corner with only the slightest hint of vignetting on some shots where the sky was visible. The image of the roses has as good of contrast as any image I’ve seen taken on a Miranda camera. Taking into account that Miranda SLRs were always seen as economic alternative to more expensive Japanese and German SLRs, I would be shocked if anyone who bought these cameras new, were disappointed at the image quality the lenses delivered. The vibrant blue lens coating on the front of the lens handles colors extremely well and reduce flare as good as any I’ve seen.

When I shot my test roll on the Automex, I never considered relying on the selenium exposure meter as the overwhelming majority of the time, I find original selenium meters to be way off, but I was shocked when Anthony told me he metered using the Automex’s match needle. It is clear that on this example, the meter is still working well both outdoors and indoors. The black and white images of the coffee barista were shot handheld wide open, using the meter and they are quite stunning!

I asked Anthony to type up a couple thoughts he had while using the Miranda Automex and this is what he said:

Miranda was a brand I was unaware of until I got into collecting cameras. No one I ever knew growing up ever had one, so when I learned of this lesser known Japanese company, I was eager to give one a try. When Mike sent me this Automex, my initial reaction when it arrived was how heavy and solid it felt. The camera’s heft and build quality suggested that of a premium camera from the era in which it was made.

I found the ergonomics very comfortable, and really enjoyed the front shutter release. The viewfinder was a tad darker than I was used to, but it was not anything that negatively impacted my use of the camera. I found the shooting experience to be quite good, and I quickly went through a couple rolls of film with ease. This isn’t something that I could have done with a problematic camera that wasn’t enjoyable to shoot. Within a very short time, I felt comfortable shooting the camera in difficult lighting situations or of closeups of my dog.

When I saw the results from those rolls, I was impressed with what I saw. Images looked as vibrant and clear as I pictured them in my mind while shooting. I saw nothing that suggested that a photographer from the 1960s wouldn’t have been just as happy with as any other German or Japanese camera. I also was impressed that the selenium meter was still accurate as I based my exposures on what the needle recommended and everything seemed to be properly exposed.

I came away impressed with the Miranda Automex. Although the build quality felt very good to me, I got the feeling that maybe this was a step down from a Nikon F or a Voigtländer Bessamatic in terms of quality, but not enough to dissuade me from using it. As a more economic alternative to top of the line professional cameras, the Miranda was a winner for me, and has opened my eyes to other cameras by this company.

I’ve shot many Miranda cameras before so I had an idea of what to expect, but otherwise, my thoughts echoed Anthony’s. I have always preferred cameras with front body shutter releases. Whether they’re flat like the Miranda or Topcon SLRs or angled like Prakticas, I find the action of pressing into the body much more comfortable than pressing down on the top plate. I wish more cameras had this feature.

The Miranda Automex is a full bodied and heavy camera. The body’s softly angled sides do a great job of making the camera feel less substantial than it really is. Comparing this body to that of the more squared off corners of a Minolta SRT-101, the Miranda feels more comfortable, and I suspect would cause less hand fatigue during an extended shooting session.

My biggest “con” to using the camera is the rather dim viewfinder. The brightness is reasonable considering its age, but it still causes indoor shooting to be problematic. I was very happy to see that a split image focus aide is present, as many cameras of this era did not have them. In my opinion, the split image can help offset a dimmer viewfinder. Neither I nor Anthony tried to shoot the camera with the viewfinder at waist level, but I have done it on other Mirandas, and other than giving you a different perspective, I don’t think it adds or subtracts anything to the shooting experience.

The Miranda Automex was definitely a huge upgrade for the company, revising the body, and adding a large number of new features not previously available on earlier models. That the same basic design was used throughout the rest of the decade into the Sensorex models shows that this was the first of many great cameras to come. It really is a shame how the company’s fortunes would change and quality control would soon suffer. That cameras like the Automex and other “alphabet” Mirandas were as good as they are, makes me wonder what might have happened had the company had better management and more success into the electronic era. Who knows, maybe today some of us would be shooting Miranda digital mirrorlesses!

Whether or not you’ve shot many Mirandas before like me, or if this is your first experience to the brand like Anthony, I think you’ll find a lot to like with the Automex. I don’t know if it is the best Miranda or even the best camera of its era, but it certainly was a good one, and definitely is not deserving of the negative reputation of the company’s later models.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Miranda_Automex,_Automex_II

https://photothinking.com/2023-01-17-miranda-automex-iii-auto-grille/

I really enjoyed the Miranda story as I bought a brand new Sensorex in 1969 and loved shooting it until it was edged out by the more compact Olympus OM-1 in 1978. Since the 1980s, it has been a shelf queen but I did test it in 2021 and it was still working well. I linked my Miranda folder, if anyone is interested.

Thanks for a great story and great work by Anthony.