This is a Minolta V3, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. starting in September 1960. The Minolta V3 was the follow up to the earlier Minolta V2 from 1958, expanding the top shutter speed to a record high 1/3000 with the clever use of its Optiper-Citizen-HS leaf shutter. Like the V2, speeds above 1/1000 start to limit the maximum aperture of the lens, favoring smaller f/stops when selecting the fastest speeds. When shooting at the top 1/3000 speed, the largest aperture that can be used is f/8. In addition to its noteworthy shutter, the V3 comes with a 6-element Rokkor-PF 45mm f/1.8 lens, a combined incident coupled rangefinder, and an uncoupled selenium exposure meter. The Minolta V3 is also unique in that it uses a ‘two stroke’ film advance, a feature not found on any other Minolta camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/1.8 Minolta Rokkor-PF coated 6-elements in 5-groups

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ Automatic Parallax Correction

Shutter: Optiper-Citizen-HS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/3000 seconds, at 1/2000 only f/4 to f/22, at 1/3000 only f/8 to f/22

Exposure Meter: Uncoupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate display

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Weight: 824 grams

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_v2.pdf

The late 1950s and early 1960s was a period of great change in the camera industry. With Japan now as a recognized maker of quality photographic equipment, new and innovative models were being released on an almost continual basis as each company strove to “one-up” each other. Advancements in the design and usability of SLRs resulted in almost continual new models hitting the market, the world of auto exposure cameras exploded in 1958 with the release of an onslaught of “electric eye” cameras, and in the world of shutter design, everyone was trying to be the fastest. Prior to the late 1950s, the fastest leaf shutters topped out at 1/500 and the fastest focal plane shutters were at 1/2000 (notable exceptions are the Zeiss-Ikon Contax II and III at 1/1250 and Univex Mercury CC-1500 at 1/1500).

In 1958, Chiyoda Kogaku was the first to market with the first mass produced camera with a 1/2000 top shutter speed in the Minolta V2. Using a special high speed Optiper-Citizen shutter, the Minolta V2 stood alone as the only consumer camera with a shutter capable of such a high speed. In 1960, Canon and Konica both matched it with the Canonflex R2000 and Konica F, both with focal plane shutters hitting 1/2000. Not to be outdone, in September 1960, Chiyoda Kogaku released the Minolta V3 a blistering fast 1/3000 top shutter speed. Combining a minimum f/22 aperture with the 1/3000 top shutter speed, the V3 could handle an EV number of 20.5. This was very useful for users of fast film in bright conditions.

If you’re wondering how Minolta was able to hit speeds of 1/2000 and 1/3000 with their leaf shutters and no one else seemed to come close, you should know that these incredibly fast speeds came with a catch.

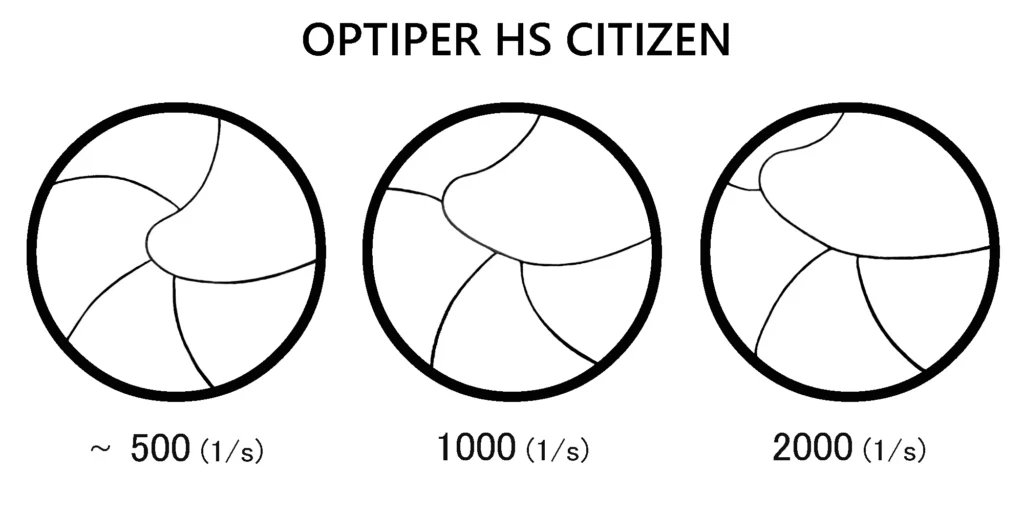

Using a clever design in the Optiper-Citizen shutters in which the shutter blades “pre-pivot” they are unable to open the maximum aperture of the lens at the fastest speeds. In the illustration below, we see the orientation of the shutter blades at 1/500, 1/1000, and 1/2000 in which the shutter blades move before firing. At these higher speeds, the shutter blades don’t actually move any faster. The blades move at the same speed at 1/500 as they do at 1/3000/. By pre-pivoting the blades, they are already partway through their motion before the shutter opens. This means that when the shutter actually does fire, the blades have a shorter distance to travel, meaning they are open a shorter amount of time. The less time the blades allow light to pass through them, the faster the shutter speed.

For the Minolta V3, this limits you to a shutter speed of 1/1000 wide open at the maximum f/1.8 aperture. In order to select 1/2000, you must close the lens down to at least f/4, and for 1/3000, it must be f/8 or smaller. While hardly a dealbreaker for someone wanting the fastest possible shutter speeds, it likely added to confusion and complexity of the design, resulting in very few other leaf shutter cameras exceeding 1/500.

With the release of the Minolta V3 in 1960, Chiyoda Kogaku didn’t just upgrade the shutter. The new camera had several other changes, the most notable being the inclusion of an uncoupled selenium exposure meter. The uncoupled meter was borrowed almost exactly from the Minolta Auto-Wide using a clever Light Value (LV) system which relied on a rotating barrel which displayed different LV numbers depending on the position of an ASA film speed dial. Simply set your chosen film speed with the knob on the back of the camera and point it at your light source. Whichever LV number the needle pointed to, you simply needed to transfer to the LV scale on the lens and proper exposure could be achieved.

In addition to the meter, another change to the camera was in the 6-element 45mm Rokkor-PF lens, who saw its maximum aperture increase from f/2 to f/1.8. This subtle increase was accomplished by improving the lens coating, which allowed for the lens diaphragm to open up just a tad larger, allowing in a bit more light wide open.

One final subtle, but significant change was for the first (and only) time ever, a Minolta camera had a double stroke film advance. In the case of the Minolta V2 and most other Minolta rangefinders whose film advance lever swung out to 220 degrees for a single motion, the Minolta V3’s was reduced to 130 degrees but required two motions to fully advance the film and cock the shutter. This was done to reduce stress on the delicate internal components which had to operate at peak efficiency for the top 1/3000 shutter speed.

Otherwise, with subtle cosmetic changes, the Minolta V3 shared the V2’s coupled coincident image rangefinder with automatic parallax correction, film compartment, focus control, and a similar overall body design.

I previously reviewed a non-working Minolta V2 as part of my Cameras of the Dead series back in October 2021, and in that review, I found several US advertisements for the camera long with retail prices of $99.95. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said about the later Minolta V3 which I cannot find mentioned in any US publications. Whether or not the Minolta V3 was sold in the US is unclear, but if it was, it most likely sold in very low numbers, as by 1960s the majority of the market was either interested in SLRs or less complicated rangefinders.

Low production numbers and a possible lack of sales worldwide have resulted in the Minolta V3 being a very uncommon camera to find today. While the Minolta V2 is not easy to find either, a quick eBay search as I write this returns eight V2s for sale and only one V3.

When handling the V3, its build quality is on par with other Minolta rangefinder and SLR cameras of the era, which is to say, very good. Japanese camera makers consistently made high quality and durable cameras in this era, before the era of cost cutting and using light weight plastics in camera construction. This is a solid feeling mechanical camera. With a weight of 824 grams, it compares to a 1980s SLR with kit lens and is something you’d definitely notice hanging from a neck strap after a long day of shooting.

Ergonomically, all of the camera’s controls are right where you expect them to be, including the film advance lever on the back surface of the camera. Even if you didn’t know it, the first time you advance the film, it is quite obvious this is a double stroke camera as the lever doesn’t go as far as most other cameras of this era. Double strokes may put less stress on the shutter, but they do slow you down while shooting. The camera has other nice features such as an automatic resetting exposure counter, and an ordinary left to right film compartment.

Loading film into the camera is uneventful. A synthetic light seal lines the door hinge and in both door channels, which although distressed on this example, still looked like they were doing their job. I would advise inspecting these on another example of the V3, if you were to try shooting one.

I generally do not like cameras with LV systems, but the one here works pretty well. Both the shutter speed and aperture rings can be turned independently of each other to find a LV number that matches the meter readout. There is no internal or external coupling like on other cameras. Using the meter is pretty simple. First, rotate a knob on the back of the camera to change the set of LV numbers which are indicated by an ASA film speed from 10 – 1600. On the slowest speed, the lowest LV number is 3, and on the fastest, it is 21. With the film speed set, simply point the camera at your light source and take note of which LV number the red needle points to. Then transfer that number to the LV scale on the lens and any combination of shutter speed and aperture that has that same LV number, will result in proper exposure.

Having a 1/3000 shutter speed is useful with slow speed films as you can still afford to open up the lens in daylight conditions to give some separation between your subject and the background or you can also use this to freeze motion when shooting fast moving objects such as race cars or athletes running. Another useful purpose would be if you loaded in a fast 800 speed film intending to shoot indoors, but needed a couple outside shots, a 1/3000 shutter speed at f/8 in direct sunlight would still be possible without exceeding the mechanical limits of the camera, like those with slower top shutter speeds would.

As this is the only Minolta V3 I’ve ever handled, I did notice that the shutter speed dial is quite a bit more stiff than the aperture ring. Most likely, dried lubricants have tightened it up in the 65 years since this camera was made, but I suspect that even when new, the additional complexity of the shutter resulted in slightly more resistance when changing shutter speeds.

Minolta’s fixed lens rangefinders from this era all had large and bright viewfinders, and the Minolta V3 is no exception. Projected frame lines automatically correct for parallax and along with a large rectangular rangefinder patch have good contrast from the green tinted viewfinder, making focus easy, even in less than ideal light. No other information is visible in the viewfinder, which would have been nice, but not completely necessary.

My first opportunity to shoot the Minolta V3 came during an especially dreary stretch of winter, and while my trusty Kodak TMax 100 probably would have been fine, I wanted a bit more speed, so I loaded in some cold stored, but expired Kodak BW400CN film. This is a chromogenic film, which means it is a monochrome color film that is designed to be developed using the C41 process. This type of film became popular during the minilab era for people who still wanted to shoot black and white, but wanted the convenience of dropping off their film at the local One Hour Photo stop who could only process color. While chromogenic films are designed to be processed in C41 chemicals, they can also be processed in regular black and white chemicals, which is what I did here when I developed this roll using HC-110b.

As you might expect, images from the 6-element Rokkor-PF 45mm f/1.8 lens were outstanding. Throughout the 20th century, Rokkor lenses have remained at or near the very top of the best lenses available. Sharpness and contrast are excellent corner to corner, without any of the optical anomalies associated with lesser lenses. Although I did not shoot any color film through this camera, I am certain based on past reputation from Minolta rangefinder lenses and their quality lens coatings, that image quality would be superb.

The Minolta V3 advertises the lens with a maximum aperture of f/1.8 compared to f/2 for the Minolta V2, which I believe is mostly marketing hype. While I’m not suggesting Minolta is falsely advertising the maximum aperture of the lens, looking at the element layout of the two lenses, I cannot see a difference. My guess is the lens from the V2 was just tweaked to get just a tiny bit more light beyond the diaphragm to increase it to f/1.8, which by the 1960s had become the norm for fixed lens rangefinders.

Minolta made a lot of terrific rangefinders in the era which the V3 was made, so any of them are going to be useful photographic tools, but by far, the biggest appeal of the V3 is its top 1/3000 shutter speed, which to be honest, is not something that I found to be particularly useful. I find that “bokeh” photography is not something to do very often and when I do it, I prefer using an SLR with an 85-135mm medium telephoto lens. I also tend to prefer film in the ASA 50-200 range. I’m not likely going to be shooting 800 or 1600 speed film outdoors where a lightning fast shutter would help me. That’s not to say I couldn’t have found an opportunity to use it, but its not something that’s going to make the Minolta V3 jump off the shelf over any other camera.

For me, my measurement of this camera was in general purpose photography, which I am happy to say it does very well. If you were to consider the 1/3000 shutter speed to be a gimmick, the rest of the camera is not. As a regular fixed lens rangefinder, it does everything it should well. I found the camera to be a tad on the heavy side and I didn’t love the double stroke film advance as I find it slowed me down, but beyond that, the ergonomics of the camera were excellent, the viewfinder with its large opening and good contrast frame lines with automatic parallax correction are as good as any out there, and the location of the shutter and aperture controls were in natural locations, requiring very little practice time before shooting the first roll.

Even the uncoupled meter with its LV system, something I often hate on other cameras, works wonderfully well. Set your film speed, look at the needle, and change the rings on the lens to match whatever number the meter says, and you’re good. For those who don’t want to use the meter, or have a camera with a dead meter, the camera is not hindered when shooting full manual. This is in contrast to cameras like some Kodak Retinas and the Voigtländer Vitessa which physically couple the shutter speed and aperture rings together. With the Minolta V3, just pick whatever you want and the camera doesn’t get in your way.

There’s everything to like, and almost nothing not to like. That said, the Minolta V3 was produced in very low numbers and is difficult to find today, especially at a reasonable price. For all of the compliments I can give this camera, what you’re likely to pay for one won’t mean it is a better camera than a Minolta Uniomat, Minolta A5, or Minolta AL-F. Heck, even the interchangeable lens Minolta Super A is easier and cheaper to find than these.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_V3

https://autowide12.com/column/minolta-v2-v3/ (in Japanese)

So did the 1/3000 speed work on your example? And if so, did it appear to be accurate (based on negative density)?