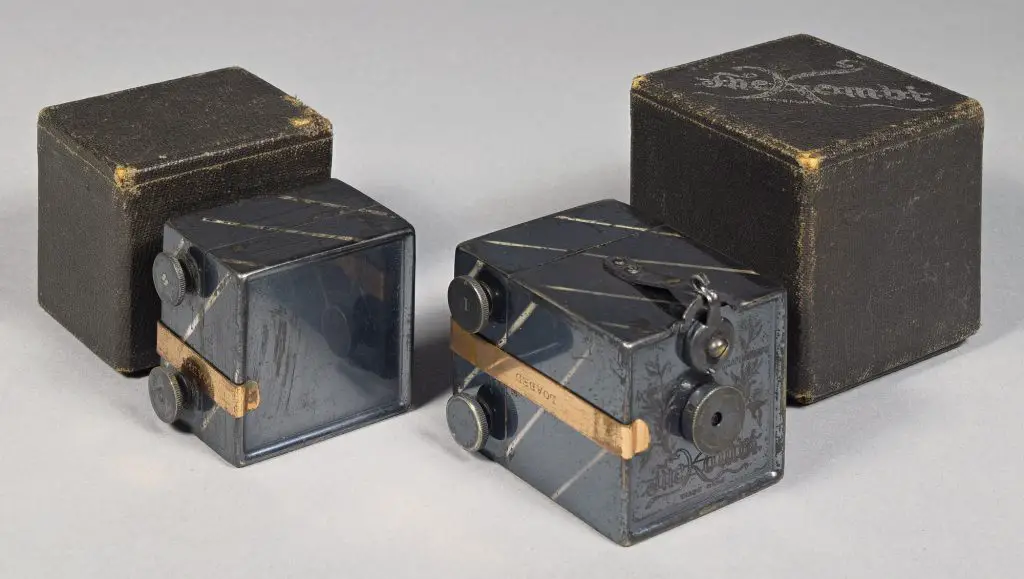

This is a Kemper Kombi, an early miniature roll film box camera and graphoscope produced by the Alfred C. Kemper Company of Chicago, Illinois, USA starting in 1893. The Kombi used a proprietary paper backed roll film developed specifically for it by the Eastman Kodak company and shot up to 25 exposures on a single roll of film. After developing film from the camera, the Kombi could also be used as a graphoscope, which was an early form of a slide viewer, in which you remove a round window on the back of the camera and look through the lens to view developed positive images. The Kemper had a variety of accessories made for it including both square and circular masks resulting of exposures in those shapes. The Kombi is considered an early pioneer in a variety of areas, including the first miniature roll film camera, first amateur snapshot camera, and first camera with interchangeable backs which could be bought separately from the camera.

This is a Kemper Kombi, an early miniature roll film box camera and graphoscope produced by the Alfred C. Kemper Company of Chicago, Illinois, USA starting in 1893. The Kombi used a proprietary paper backed roll film developed specifically for it by the Eastman Kodak company and shot up to 25 exposures on a single roll of film. After developing film from the camera, the Kombi could also be used as a graphoscope, which was an early form of a slide viewer, in which you remove a round window on the back of the camera and look through the lens to view developed positive images. The Kemper had a variety of accessories made for it including both square and circular masks resulting of exposures in those shapes. The Kombi is considered an early pioneer in a variety of areas, including the first miniature roll film camera, first amateur snapshot camera, and first camera with interchangeable backs which could be bought separately from the camera.

Film Type: Kombi Paper Backed Unperforated Roll Film (~32mm wide), 25 1⅛ inch round or square exposures per roll

Lens: unknown focal length (~28-35mm) uncoated single element meniscus

Focus: Fixed Focus (~6 feet to infinity)

Viewfinder: None

Shutter: Spring Tensioned Rotary

Speeds: Timed (Bulb) and Instant (~1/30 second)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 140 grams

Manual: https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/rl/01476/01476.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kemper Kombi is one of the earliest miniature cameras that was meant to be used by the novice photographer and be capable of good images. The camera is very small and has ornate engravings making for an excellent display piece. In use, the camera is very easy to use and produces 28mm wide round images with good sharpness. Loading the camera is very difficult however, as the camera uses a proprietary size film which has no modern equivalent. Even if you attempt to cut down larger film to fit the Kombi, loading it is not easy. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 50% | |

| Bonus | +1 for innovative design, compact size, and cool factor | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.5 | ||||||

History

Photography defined as the ability to permanently capture light on some form of light sensitive surface to be viewed at a later time has been around for nearly 200 years. Ever since the earliest forms of photography were developed in the 1830s, photographers have been finding new and innovative ways of furthering their craft.

For those who witnessed those early days, they likely saw it as a form of magic, freezing time in glass and metal plates. As the 1800s progressed, photography evolved from mysterious alchemy to a valid art form. Photographers opened studios everywhere, sometimes even in hotels. For those who wanted a photographic portrait, you merely needed to find the closest studio, put on your best clothes (or in some cases, die), stand still for a couple of minutes, and pay the man or woman to take your photo.

By the end of the 19th century, photography got easier and smaller. No longer was a chemistry background and impossibly large and heavy equipment a necessity to make a photo, as simpler dry plate and roll film cameras started to make photography more accessible.

The camera that is generally accepted as the first “consumer” camera was George Eastman’s original Kodak camera from 1888. The Kodak was a simple box camera with a rotating shutter design that was cocked by pulling a string wound on a coiled spring, and was factory loaded with enough photographic film to capture up to 100 circular images per roll. If you were so inclined, the user could open the camera and develop the images his or herself, but for most people, after finishing a roll you sent the entire camera back to Eastman and they would develop and print your images for you, reload the camera with a new roll, and ship it back to you, all for $10.

Other than the Kodak’s clever barrel shutter, there really wasn’t anything innovative about the camera as it used technology that other camera makers had prior to it’s release. By far, the Kodak’s best attribute was how simple everything worked together. Using the slogan, “You Press the Button, We Do the Rest”, George Eastman connected with the average person who had no interest in learning photography, but wanted to make their own photographs. The Kodak was a tremendous success and launched a whole industry of simple and easy to use box and folding cameras that would usher in a new century.

A couple years after the original Kodak was released, a man by the name of William Vivian Esmond patented a new type of simple box camera which US Patent documentation referred to as a Combined Camera and Photograph Exhibitor. Esmond’s camera was given patent number US488,331 and was issued on December 20, 1892. On the second page of the patent documentation, it lists that one half of the patent be assigned to Alfred C. Kemper, “of same place”.

Although the camera illustrated in this patent documentation resembles what would become the Kombi, the hand drawn illustration looks like a bit different. Imprinted onto the back door of the camera is a reference to a patent date of Dec 20, 92 which matches that of US488,311, but doesn’t list an actual patent number.

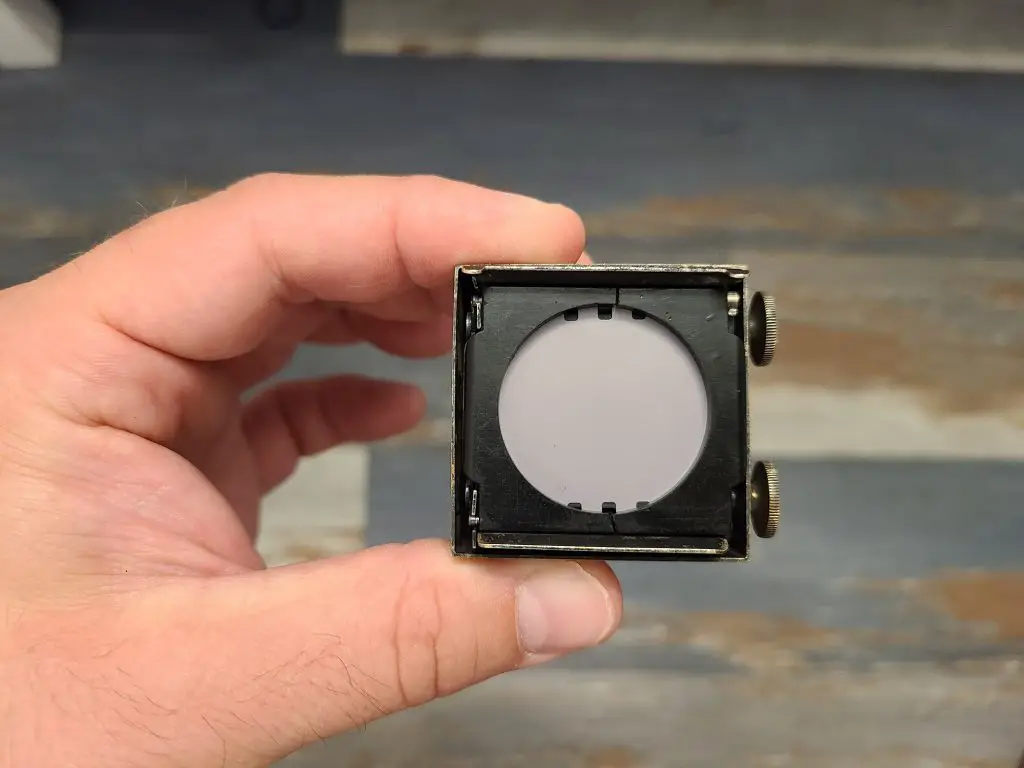

Most sources agree that within a year of this patent date, the Kombi Combined Camera and Graphoscope would go on sale for the cost of $3.50 and each roll of film, good for 25 exposures was 20 cents. For $3.00, an owner could buy a complete Kombi developing kit, containing all chemicals and tools needed to develop film themselves, or if you so chose, could send the camera back and have the film developed for you at a cost of 15 cents for developing and 1 cent each for a print of a developed image. A clever feature of the Kombi was that additional backs could be ordered with a cover to have fresh rolls of film ready to be swapped out after 25 exposures were made, without having to first develop and reload the camera. Each additional back could be ordered with a fresh roll of film, plus a cover for it, for an additional $1.50.

When adjusted for inflation, $3.50 for the camera, $1.50 for a new back, and 20 cents for each roll of film compare to $103.85, $44.50, and $5.93 today making the Kombi one of the most affordable photographic options available at the time. Compared to Eastman’s Kodak camera which sold for $25 for the camera and $10 to have each roll of film developed and reloaded, the Kombi was a bargain.

Despite competing with Eastman’s Kodak camera, it was Kodak themselves who produced the proprietary film for the Kombi. Contrary to some information found on the Internet today, the Kombi does not use 35mm film, rather a slightly narrower film stock that I estimate to be about 32mm wide. Considering the metric system was not widely used in the 1890s, a conversion of 1.25 inches equals 31.75mm which likely was the actual size, but I found no official reference to the Kombi’s film, other than it exposes images of 1.125 inches wide.

How and why Eastman became the sole producer of the Kombi’s film is not clear, but a theory I have is that Eastman wanted to test the waters for such a simple and small camera like the Kombi before producing a similar model themselves. Two years after the Kombi’s release came the Pocket Kodak which although not quite as small as the Kombi, produced 1.5″ by 2″ images on 102 format roll film.

In my research for this article, every single search I did for the names Alfred C. Kemper or William V. Esmond came back to the Kombi camera, but strangely, I found no other information about what else either man did. I found street addresses for Kemper’s company at both 132-134 Lake Street, Chicago, and also 208 and 210 Lake Street Chicago, suggesting that the company changed addresses at least once. Other references to offices in both London and Berlin suggest the company had expanded internationally, but strangely, I found absolutely no reference to anything else Kemper did. William V. Esmond’s name appeared on a couple other camera related patents after the original US488,331 patent, but it’s not clear if any of his inventions were ever produced. It is also not clear what else Alfred C. Kemper did before and after the sale of the Kombi.

“All About the Kombi” scan above courtesy, Pacific Rim Camera.

The Kemper Kombi seems to have been moderately successful as they are not hard to find today, but in my research for this article I stopped seeing references to it after 1896 which suggests a short life span. In some advertisements for the camera from the mid 1890s, Kemper claimed that more than 50,000 were produced in a single year which if true, combined with a 4 year production run, suggests that as many as 200,000 could have been made. The number is probably somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000, but it’s not likely we’ll ever know the true number.

I also do not know for how long the film continued to be produced. Many times, an extinct film for a camera that is no longer being made, will continue to be produced for purchase by existing customers, so it’s likely you could still buy Kodak’s film for at least a few years after the camera ended production.

Today, the Kemper Kombi is a very collectible camera for many reasons. For starters, it’s all metal and solid construction means that many have survived much better than other wood and paper cameras that were common in the era. Adding to that the camera’s compact size, good looks, curious operation, and historical significance only adds to the camera’s appeal. As I write this, five examples of the camera are available on eBay, which doesn’t seem like a large number, but for a 130 year old camera, the fact that at any given time, at least one is always for sale, I’d consider that “easy enough” to find.

My Thoughts

With the number of reviews of cameras on this site approaching 300 (I honestly haven’t counted), The oldest working camera I’ve managed to shoot is the Kodak No.1 Autographic Special, Model A from 1916. I did post a Camera of the Dead review of the Kodak No. 3A Folding Brownie from 1909, but without any film to shoot with it, I never made any exposures. So when I had an opportunity to not only review, but also shoot my first 19th century camera, I was definitely excited to give it a shot.

This Kemper Kombi belongs to my friend and fellow blogger, Mark Faulkner who had never gotten around to trying it out so he gladly packaged it up and sent it to me earlier this year. I knew the Kombi was small, but I was not prepared for exactly how small it was. Measuring barely over an inch tall and wide, and about 2 inches deep, the Kombi is not only the oldest, but is also the smallest camera I’ve ever used.

The body is almost entirely made of metal with the only exceptions being the single element glass lens, and both a film platen and mask which are made out of some sort of composite material that resembles Bakelite but can’t be as Bakelite had not yet been invented when the Kombi was produced. The total weight of the camera is 140 grams which is very light, but considering the incredibly small size of the whole package, gives the Kombi a reassuring feeling of density.

Edit 7/20/21: After posting this article, Reddit user u/absolutenobody keenly pointed out that the material is most likely Ebonite, which is a type of hard rubber commonly used at the time. Originally developed by Goodyear, Ebonite was used in a huge number of things from slide holders to bowling balls, until it was eventually replaced by other synthetic plastics in the early 20th century.

In use, the Kombi works much like any number of early 20th century box cameras in which there is a single shutter speed that can be shot in Instantaneous and Timed modes. Focus is fixed, as anything from about 6 feet to infinity will be within the meniscus lens’s depth of field.

The Kombi lacks a viewfinder, which might seem odd, but was actually pretty normal for the era as the original Kodak Brownie didn’t have a viewfinder either. While shooting, simply point the camera in the general direction of your subject and press the shutter release. I’ve never found any specifics about the focal length of the meniscus lens, but it’s definitely wider than 50mm, meaning that there is great depth of field and coverage so getting what you want in the image isn’t that difficult.

Another thing missing from the Kombi is an exposure counter. With film loaded into the camera, a small little finger on one of the film spools makes a clicking noise as it passes a metal spring in the film compartment. I’ll cover how this works more in the section below (including a video where you can hear it) about loading film into the camera, but with film loaded, turn one of the advance knobs until you hear three clicks and you are ready for the next exposure.

Two knobs on the camera’s right side are numbered I and II and both can be used for film transport. The Kombi’s instructions say to load a fresh roll of film on the I spool, and advance it to the II spool, but looking at how everything works, I don’t see any reason you couldn’t load it the other way. Whichever way you choose, you must remember to be consistent throughout the duration of the roll.

When it’s time to fire the shutter, you must move the spring loaded metal arm across a curved plate with two indentations in them. The middle spot is used for long or Timed exposures, so should only be used in very low light. If you want to shoot the camera using the single Instant speed, you need to move the arm all the way to the opposite indentation and fire it by pressing down on the arm to allow it to spring back to it’s original position. Although I could find no information about the speed of the Instant setting, I estimate it to be around 1/30 based on the exposures I got later in this review.

Warning: Both cocking and firing the shutter are done in the same motion, so as you cock the shutter, you are also opening it, exposing the film inside to light. It is very important to cover the lens when cocking the shutter, or else you’ll ruin your exposure. Only after moving the curved arm all the way to the opposite side will the shutter be ready to fire. Pressing down on the arm will fire it as it moves past the middle position. If this doesn’t make sense, look through the lens as you cock it, and you’ll see the shutter is always open when the arm is in the middle position.

The Kombi has a single speed shutter and no provision for adjusting aperture, but if you wanted to reduce light entering the lens, an original accessory that slipped over the lens with a smaller hole would effectively “stop down” the lens. In the image to the left, this cover is over the lens. When not needed, you just pull the cover off and be sure not to lose it!

Although most people see the Kombi only as a camera, it also doubles as a Graphoscope, which is another name for a slide viewer. Of course, in order for a slide viewer to work, you need slides, and the proprietary film Kodak made for the Kombi was a negative film, so in order to use this feature, after developing your negatives, you’d need to contact print them onto a transparent film to make a positive. According to the Kombi’s user manual, you could also order premade transparencies of “celebrities, statuary, paintings, views, etc.” for an additional 60 cents.

To use the camera as a Graphoscope, you must first load the developed images into the camera and onto the spools in the same manner as you would load the film. For obvious reasons, you would not include the film platen or the original backing paper that would have come with fresh undeveloped film as you need to physically see through the developed film.

After loading the camera, a round window on the back of the camera must be removed by rotating it counterclockwise and lifting off. With the back open, you would then set the shutter to Timed mode to allow light to pass through the lens, and then put your eye up to the lens and look through the camera with a light source entering the back of the camera to illuminate the transparent image. With either of the Kombi’s two wind knobs, you can go forward and backward on the roll of transparency film to re-view images you’ve already looked at.

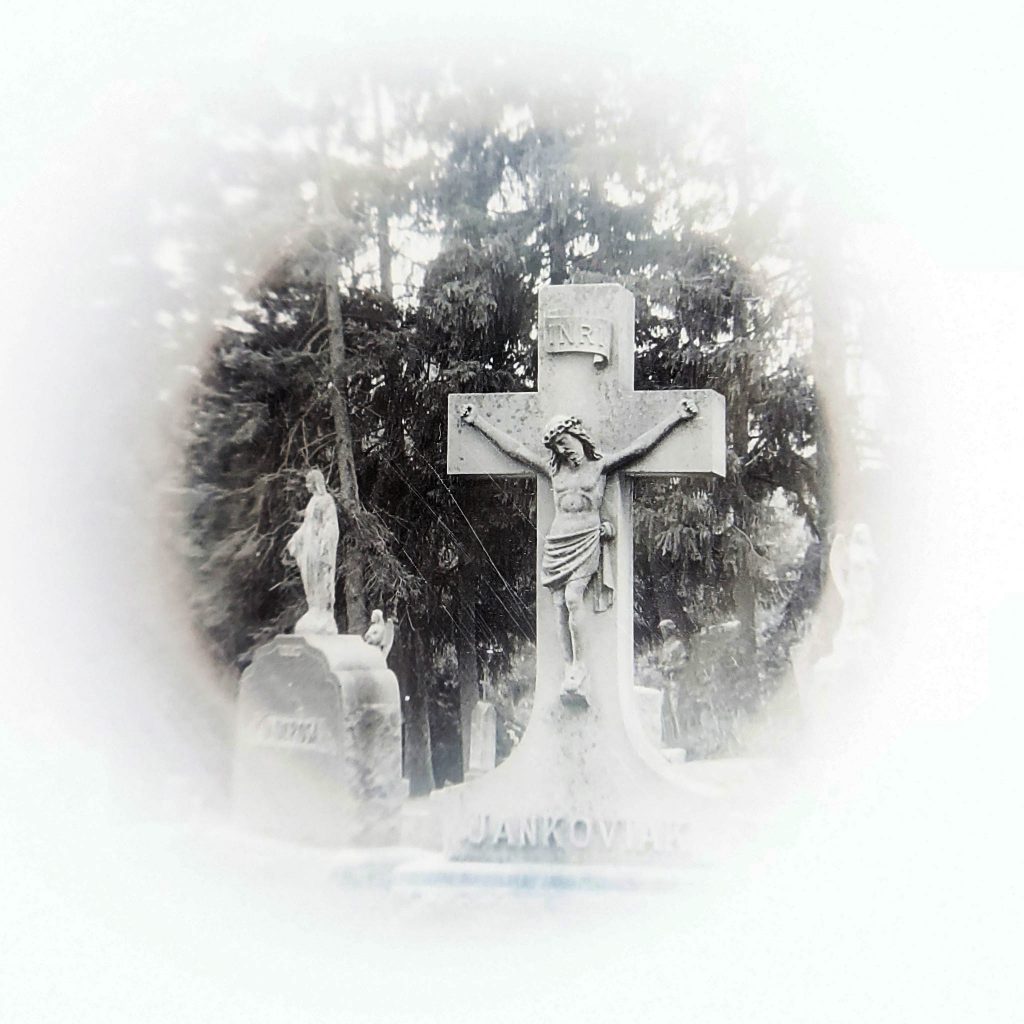

Without having access to real Kombi transparencies, I cheated a bit by taking a black and white 35mm negative and cutting it to a square and inserting it into the film plane of the Kombi, opening it up and shooting through the lens with my cell phone. I didn’t have any slide film for this experiment, so I inverted the image in Photoshop to give you an idea of what it might have looked like. The performance of the Kombi’s meniscus lens as a Graphoscope is more than adequate as center sharpness is excellent to the naked eye, although there is quite a bit of softness near the edges.

Loading Film

The Kombi is a pretty simple and straightforward camera to use. At it’s low cost and simple operation, I can see how it would have appealed to those without any previous experience with photography as it breaks everything down to the basics.

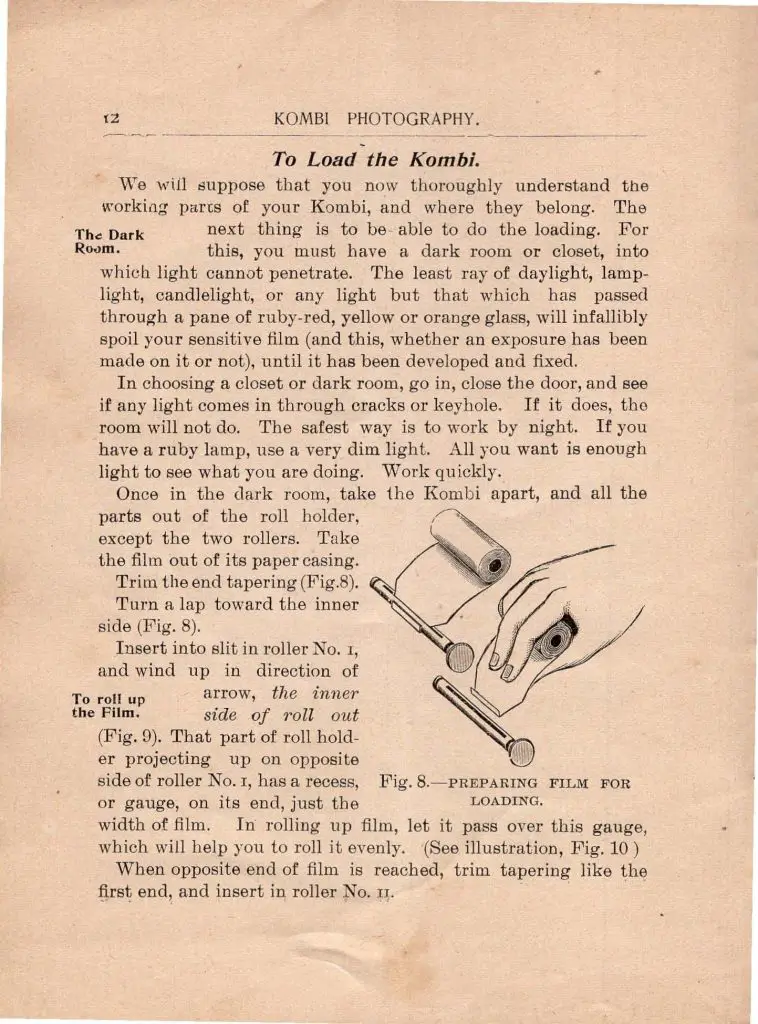

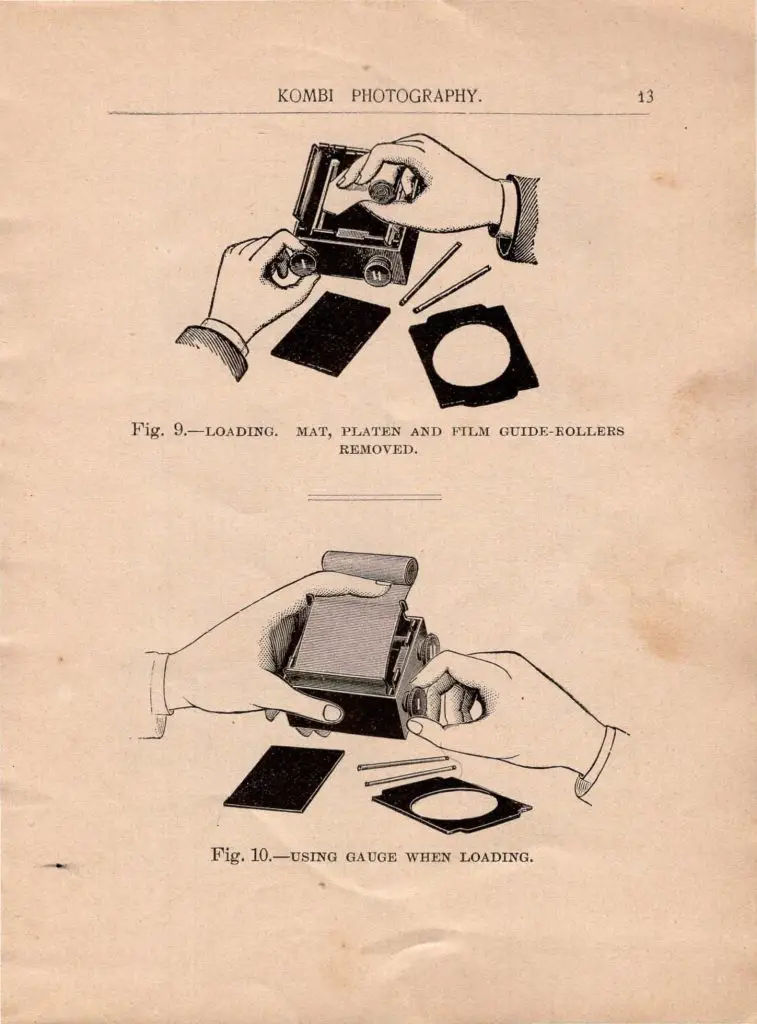

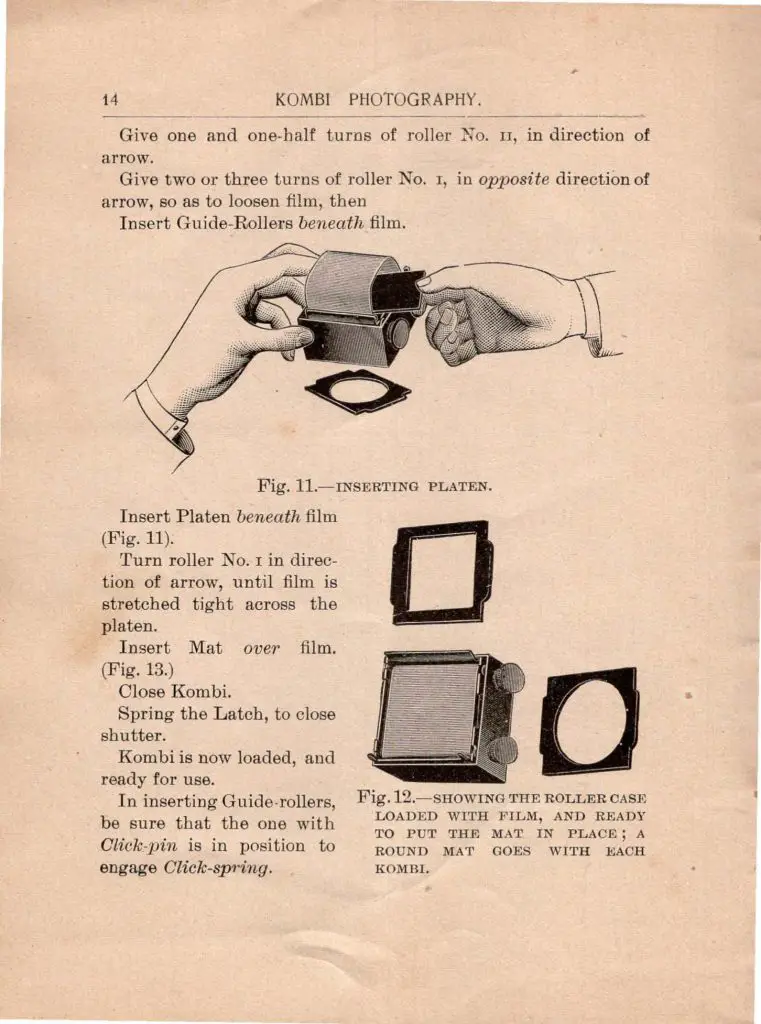

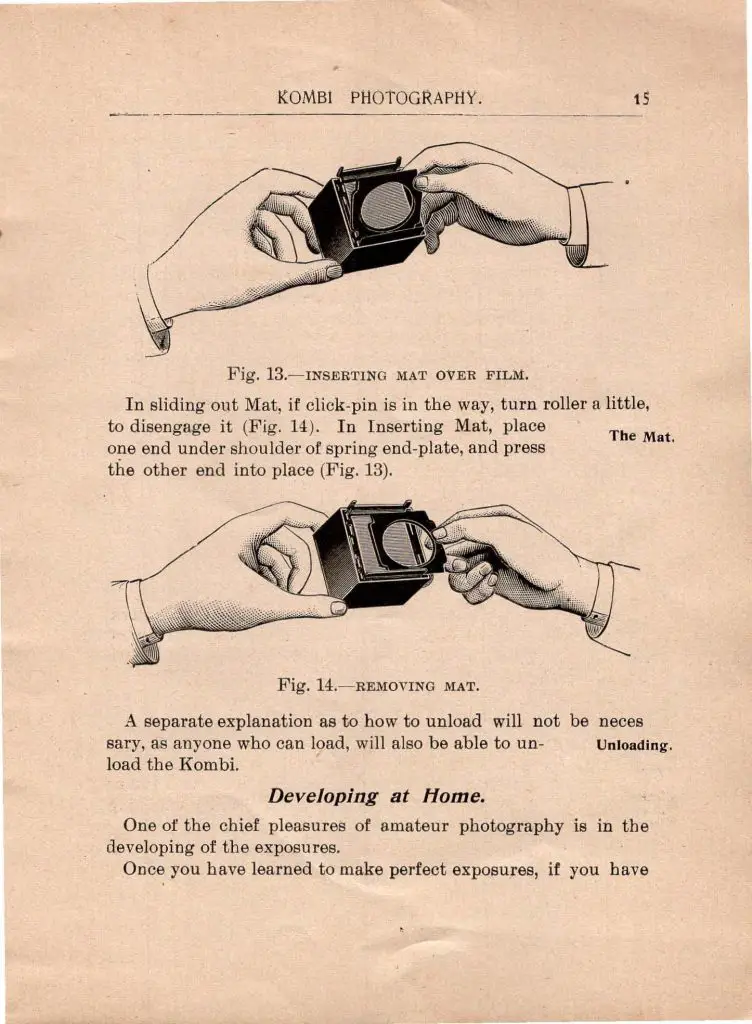

When it comes to loading film in the Kombi however, some extra patience is definitely required as the process is not easy. The Kombi’s original manual dedicates almost four complete pages, along with seven illustrations to explain the process which must be done entirely in the dark. Adding to the difficulty, doing this without access to genuine Kombi film makes it even harder as the original film would have had a protective backing paper which would have made attaching it to the spools a little easier.

A Word About Kombi Film: There are many articles that group the Kombi into a vague category of early miniature cameras, and it’s not always clear exactly what kind of film the camera used. In my research for this article, I found no mention anywhere of the exact width of the film Kodak made for the camera. Some sites refer to it as 1.5″ film, which is incorrect. Others suggest that perhaps the Kombi can use unperforated 35mm film, and that is not correct either.

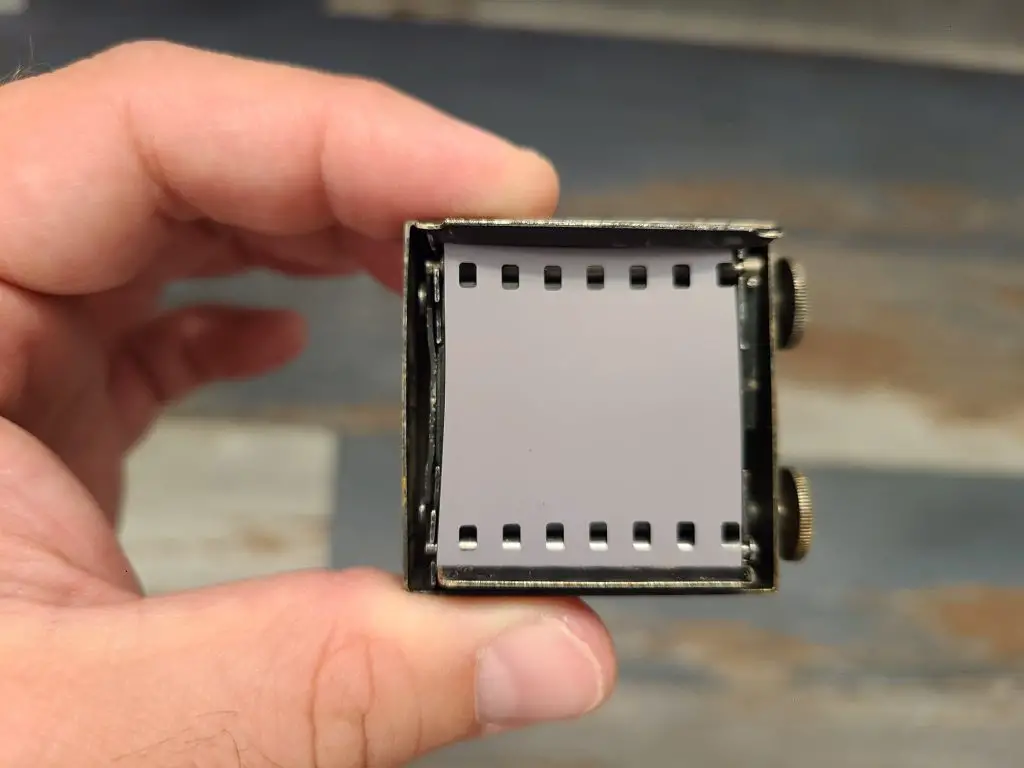

I initially attempted to hand roll some bulk 35mm film and it definitely does not fit. 35mm film is about 1mm too wide on each side, suggesting the exact width of the film gate is about 33mm. To allow for a tiny bit of tolerance so the film doesn’t constantly rub against the edges of the camera while transporting, I feel safe in saying that 32mm film is required to transport through the camera. The Kombi shoots one and one eighth inch images, which converts to 28.5mm, meaning that with 32mm wide film, you should have slightly less than 2 mm of extra space on each side.

The gallery above shows the four pages from the Kombi’s manual (courtesy Pacific Rim Camera) and it does a really good job of explaining the process, but in practice, it’s quite difficult to do as it all needs to be done in complete darkness and you must attach the film to both spools as leaving it loose on one spool will just cause the film to freely flop around in the camera and not lay flat. If this was something you wanted to do yourself, I would definitely recommend using an orthochromatic film so that you can do this with a safe light on which will help as fumbling around with the various small pieces in complete darkness is really difficult.

In my own attempts to shoot this camera, I grew increasingly frustrated at my inability to get the film attached to both spools, inserting two rollers in the correct orientation (remember one of them has a little finger that makes a clicking noise as you advance the film), the two halves of the circular mask (which was broken before I got it), and the platen, all without anything falling out. The few times I did manage to get things together, I found that before I could close the camera up, the film leader had come out of the little slit in the spool meaning that the spool would just rotate freely without spinning the film so I had to keep starting over. I finally had some luck after deciding to just tape the film directly to each spool instead of threading it through the slit.

Although the instructions from the original manual are quite detailed, they require original Kombi film with the original paper backing which is very difficult to find today. I ended up having to custom cut some 120 roll film down to ~32mm and use that without any backing paper. After a lot of trial and error, I finally got it and thought it would be more helpful if I made a video to show you the process. Check out the video below, not only to see how to load film into the camera, but I also show how to count exposures, and what it looks like to see film transporting through the camera.

If the instruction and the video above seem like more than you’re willing to attempt, there is a simpler way to shoot film in the Kombi, but at the expense of only being able to shoot one single exposure at a time.

Rather than load in a roll of film and attach it to the spools, you can simply cut a square of 35mm film and lay it flat on top of the rollers, under the mask, and then reassemble the camera. I found it was easier to place the film sideways in the camera, but depending on how you cut it, it can fit both ways. Unperforated 35mm would be better as the sprocket holes will get in the way somewhat, but it does work. Just be sure to remember to set the film with the emulsion side facing up.

The images below show two squares of film in the camera. Of course, you need to do this with the lights off, as I sacrificed this one square of film with the lights on so I could take these pictures.

This second method is definitely easier, and with practice, I can cut a square of film, load it into the camera, and close it back up again in less than 2 minutes. Whichever method you choose, at least know that what you’re doing is something that very few people within the last century have attempted.

My Results

Not having access to real Kombi film, I had to get creative by loading in single exposures of film as described in the section above, but knowing that there likely hasn’t been a Kemper Kombi in active use in quite some time, I figured it was worth the extra hassle. Truth be told, after doing it several times, I was able to complete the entire loading process in less than 2 minutes per exposure. The biggest hassle was taking the camera some place interesting to make an exposure, and then knowing I had to take it back home again to reload it. This resulted in a lot of extra time needed to get multiple exposures for this review.

My choice of film was bulk Kodak Plus-X 125. I chose this film as I was afraid that with the Kombi’s single shutter speed and very small aperture, slower films would not expose correctly, and knowing that there would be a learning curve to getting images from this camera, I didn’t want to waste any of my better film stocks. With a huge supply of Plus-X, I thought it had the right balance of speed and grain that would give me the best chances at getting usable images from.

It would actually take me three different cycles of shooting and developing before I got usable images from these first single exposure experiments. I’ll save you the details, but I could have saved myself a lot of time if I had RTFM. In total, the above two images were the only worth sharing. The one of me is a bit soft as I am a little bit too close to the camera, but at least proves I really did use the camera, and the one of the Pioneer receiver is the only one I attempted in Bulb mode, holding open the shutter for about 3 seconds.

After having some limited success with my single exposure method, I really wanted to use this camera with roll film, like it was intended. I reached out to my good friend and vintage film hacker, Adam Paul and asked if it would be possible for him to custom cut me some 32mm wide film that was narrow enough to fit on the Kombi’s spools, but wide enough to capture a 28mm circular image.

With this challenge in front of him, Adam got to work, and cut down some ORWO UN54 film into 12 inch strips exactly 32mm wide. Knowing that the Kombi has a single shutter speed and no iris, he picked UN54 as it’s ASA100 speed rating and incredible latitude meant it should expose correctly in the camera.

The images above are what I think are the first to be shot in a Kemper Kombi in decades, perhaps even half a century or more. In my research for this article, I found absolutely no evidence of new images being shot in any contemporary review, or even those in published magazines in the second half of the 20th century. The few references to the camera I did find which showed sample images, always featured images shot when the camera was current, and later rescanned.

A combination of the camera using a type and size of film that no other camera has ever used and hasn’t been made in over a century, plus, an extremely difficult loading process likely turned off anyone wanting to give it a try. If you have, or know of someone who has shot recent images in a Kombi besides mine, please let me know.

Image quality is, well, the best you’ll ever see from an almost 130 year old palm sized all metal box camera with no viewfinder. Like all cameras with single element meniscus lenses, center sharpness is quite good with a significant drop off in sharpness near the edges. When the Kombi was sold new, you had the option of circular and square masks, and looking at the circular fall off with these images, I cannot imagine anyone would want to use the square mask as the corners would have been worse.

There’s artifacts all over the images including scratches, orbs, finger prints, and in some cases where my images went off the edge of the hand cut film I was using, but none of these are complaints, in fact, I would say they add to the appeal of the images. If you were to close your eyes and imagine what you would think circular images from an 1890s box camera might look like, these are it!

Using the Kombi is a lot of fun, especially with roll film in it because I didn’t have to keep taking it back home into a dark room to extract the single images. Having to listen for three clicks in between each image worked surprisingly well. I did have a small amount of overlap between some images but that was likely user error as most of the time there was sufficient frame spacing.

In using the camera, it seems the minimum focus is about 6 feet, judging by the mirror selfie which is a tad soft and I am about 4 feet from my reflection. I initially pegged the shutter speed at 1/50 like most Kodak box cameras, but each of the ORWO exposures came out a bit overexposed, so I would estimate the shutter is slower than that, probably closer to 1/30. The lens is also clearly on the wide side. Once again using the mirror selfie as reference as I shoot myself in that same mirror with many cameras, I know that with a 50mm lens on 35mm, at the distance I am standing, I cannot see both edges of the mirror. My best estimate is the lens produces images somewhere between 28-35mm on 35mm film.

I genuinely liked using the Kombi and loved the aesthetic of the images it made, but not having access to the proper film makes repeated use prohibitive. Although this camera is a loaner, I doubt that even if it were in my permanent collection, that I would ever shoot it again beyond this review. It simply requires too much effort to cut the film, load it, shoot it, then develop it (32mm film does not fit properly on a Paterson tank reel), and finally scan it (it also doesn’t fit on normal 35mm film holders).

Still, what an experience. Considering how much more difficult photography was in 1893 when this camera was first invented, the challenges I encountered were likely child’s play back then. Although I do not know how many of these cameras were ever made, the fact that many are in collector’s hands today suggest a decent number were made, and if so, people obviously bought them. For the time they were made, they were the cheapest camera you could buy and one that likely started many people into the world of photography.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.vintagephoto.tv/kombi.shtml

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=15296

http://www.submin.com/large/collection/kombi/introduction.htm

https://thegashaus.com/2020/10/06/a-c-kemper-kombi/

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/18983-the-kombi

WOW! Amazing persistence on your part, and fine images that look decidedly 1900-ish. Eastman may have “offered” to produce the Kombi film as a way of controlling their competition. Eastman bought out Rochester Optical (Poco cameras) and American Camera, thus effectively capturing the best ideas from his rivals. Ol’ George was a good design engineer, but more importantly a brilliant marketer.

That is my guess too. Eastman was a shrewd businessman, like you said, and with the release of Kodak’s own Pocket camera only 2 years later, suggests they saw enough demand for roll film cameras of this size to do it themselves.

Insanely awesome! Some pretty impressive results- I love the one of the Elzinga Farm Market

Thanks Kurt! That one of the farm market was done out the window of my car as I sat at a red light. That market is on US Route 30 by my house and I pass it multiple times a week. Sometimes the most random shots turn out to be the coolest!

Great article! I didn’t see where you mention the “loaded” clip. It’s a nice little feature to remind you there’s film inside!

I’ve seen the “loaded” clips online, but oddly, the one I have the clip doesnt say that. I do refer to it in the film loading video strongly recommending you put it on to help keep the camera closed, but yeah, that is an extra measure of safety.

Thanks for a fascinating review, Mike! So of course, immediately after reading it I checked eBay for any Kombis for sale. I figured my experiences with loading and shooting a Soviet KGB F-21 Ajax would help prepare me for a Kombi. But after checking the prices, I decided to wait until after I win the lottery.

Yeah, I saw that too. I don’t think there will be any type of “Mike Eckman effect” as the prices on these were already high! 🙂

Brilliant, well done Mike.