This is an Alpa Alnea Model 7 made by Pignons S.A. of Switzerland starting in 1952. It was the 4th and most advanced model of the second generation of Alpa cameras. Featuring both a 45 degree angled reflex viewfinder and a coupled coincident image rangefinder with selectable 50, 90, and 135mm masks, it was truly both an SLR and a rangefinder in the same camera. Alpa cameras are highly sought after by collectors due to their unique design and extremely complex built quality. Like a Swiss watch, Alpas are often considered to be luxury, precision built instruments that were a step above everyone else.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Kern-Switar Apochromat coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Alpa Bayonet

Focus: Variable

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Fixed 45 Degree Pentaprism

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: P (Bulb), 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: FP and X Flash Sync at 1/50

Weight: 842 grams (w/ lens), 656 (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/alpa/alpa_reflex_7.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Alpa 7 was the most advanced of Pignon’s second generation of Alpa cameras. Released in 1952, it has both a rangefinder with an adjustable focal length, and a 45 degree angled pentaprism. It was a fully loaded and top of the line camera upon its release and one that is still quite valuable today. The Alpa 7, like all Alpas are hand built precision instruments using the latest technology and best features that were available at the time. The camera is loaded with quirks and is both fun and frustrating to use. The lenses I had access to in this review were excellent and produced razor sharp images, comparable to those of the best German and Japanese models. If you ever have an opportunity to handle one, I highly recommend it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall coolness, one of the most unique cameras I’ve ever handled | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

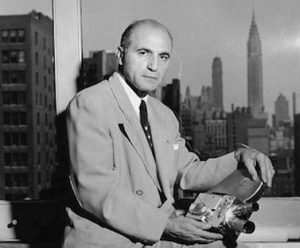

The history of the Alpa camera can be traced to a man named Yakov Bogopolsky, a Russian Jew born in Kiev in December 1895. Not much is known about Bogopolksy’s younger years, but we do know that he moved around a lot, and with each new location, he changed his name more than once.

At some point in his youth, he relocated to Switzerland and by 1914, had enrolled in college in Geneva to study medicine. Now known as Jacques Bolsky, he would eventually change his field of study to mechanical engineering and would show an interest in photography, namely motion picture cameras.

By 1923, Bolsky had designed his first 35mm cine camera, known as the “Bol Cinegraphe” which made its debut at the Swiss National Exhibition of Photography. The Bol Cinegraphe was unique in that it could be used both as a motion picture camera, but also a projector. The camera attracted enough attention that Bolsky had received financial backing from some bankers and a man named Charles Haccius, and formed his own company, simply known as Bol S.A.

Over the course of the next several years, Bolsky and Haccius would design a variety of cinema film cameras. Earlier models used 35mm film, but due to the rise in popularity of smaller film stocks, they would primarily create 16mm film cameras. One of the company’s first successes was the Bolex, a feature rich 16mm motion picture camera that had interchangeable lenses using the cine C-mount.

The Bolex was quite popular and sold well, and as a result would become the name of the company at some point in the 1920s. Bolex would design a variety of different 16mm and eventually 8mm variants of the Bolex, but would run into financial trouble around 1929. At this time, Bolsky would reach an agreement to merge with the Swiss company Ernest Paillard & Cie who made a variety of products like gramophones, typewriters, and music boxes. On September 30, 1930, Jacques Bolsky would sell a majority of his assets and patents to Paillard who would continue manufacturing Bolex cameras under the name Paillard-Bolex.

Bolsky would continue working as a chief designer for Paillard until around 1935 at which time he ventured out on his own. For a short while, he was employed by another Swiss watchmaker named Pignons S.A. and would once again design a new camera. This time, it would be a 35mm still picture camera which would eventually be known as the Alpa-Reflex.

The Alpa-Reflex was a precision all metal single lens reflex camera that was aimed at the high end of the market to compete with top tier German marques like Leica and Contax. Alpa-Reflex cameras were hand made by technicians which resulted in very low production numbers. Alpa-Reflex cameras were expensive and rare back in the 1940s, and even more so today. On the used market an original Alpa-Reflex camera in good condition can fetch prices over several thousands of dollars.

Bolsky did not stick around with Pignons long, and in 1939, perhaps to flee anti-Jewish sentiment from nearby Nazi controlled Germany, Bolsky would relocate to the United States and once again change his name to Jacques Bolsey where he would initially work for Graflex, but would later form his own company, eventually producing a line of Bolsey cameras. In his time working for Pignons, Bolsky only ever saw prototypes of the Alpa and never saw the finished product.

Initially, production of the prototype cameras was very slow. Not only was Pignons not a camera company, but Europe was at war, and it was difficult to acquire the resources to come up with an all new camera design. Despite these challenges, Pignons persisted and between 1939 to 1941, around 20 prototypes were created with names like Bolca Reflex, Teleflex, and Viteflex. Around 1942 a second batch of prototypes was created, this time with the name Alpa Reflex.

The new camera wouldn’t make its first public appearance until April 1944 at the Swiss Trade Fair in Basel, Switzerland. At this time, all Alpa cameras shared a similar body design, with only incremental updates being made along the way. Between the years 1944 and 45, less than 550 cameras were made. Each model had a waist lever viewfinder and a coupled rangefinder in the body. A few rangefinder only cameras were produced without the waist level finder.

Between 1946 and 1951, production increased somewhat with about 6350 being made in that five year period. This was a big number for a Swiss watch maker producing their first camera, but was very small compared to pretty much any other camera maker out there.

In 1949, a revised version of the original Alpa called the Alpa Prisma-Reflex was introduced which contained a 45 degree angled pentaprism viewfinder for eye level photography. This was a revolutionary feature in SLR design first seen on the Italian made Rectaflex and Zeiss-Ikon Contax S. The 45 degree angle was unique to Alpa and according to Pignons, was said to be more convenient to the photographer, but also due to the reduced angle of reflected light through the pentaprism, offered a brighter image.

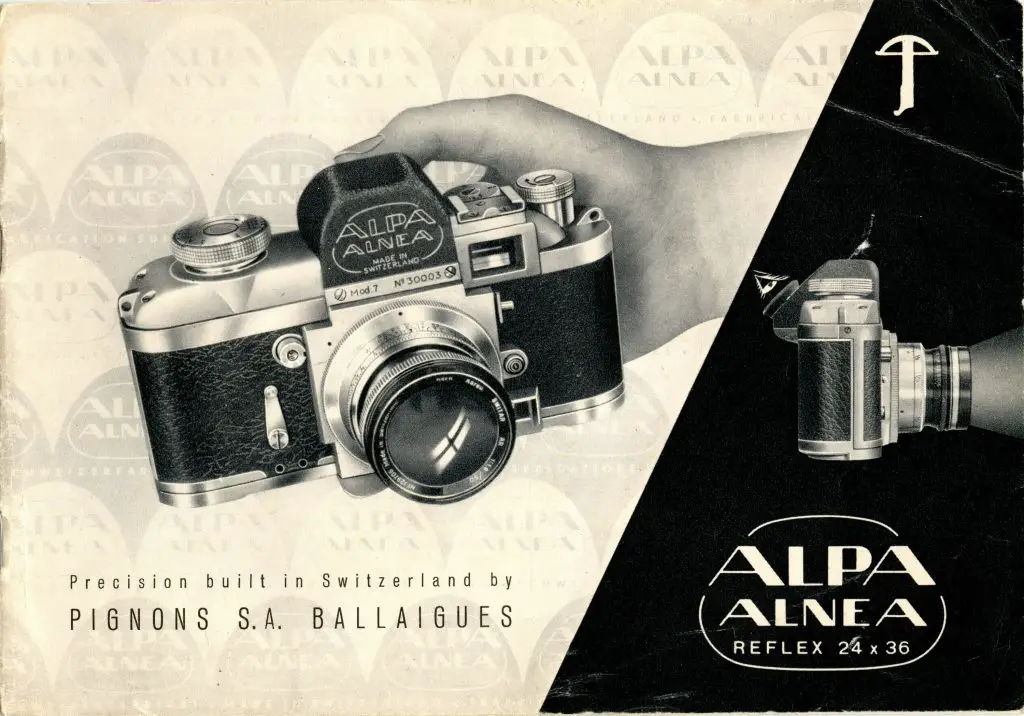

In 1952, Pignons would release an all new second generation Alpa camera with a significantly redesigned body, an all new and much larger bayonet lens mount, and one that used more machined parts. Early second generation Alpas were called Alpa Alneas which stands for “all near”, but the Alnea suffix would later be dropped, replaced with “Reflex”. Also with the second generation, Alpa began a model numbering sequence starting with the Model 4 that they would continue with throughout the rest of their time as a camera maker.

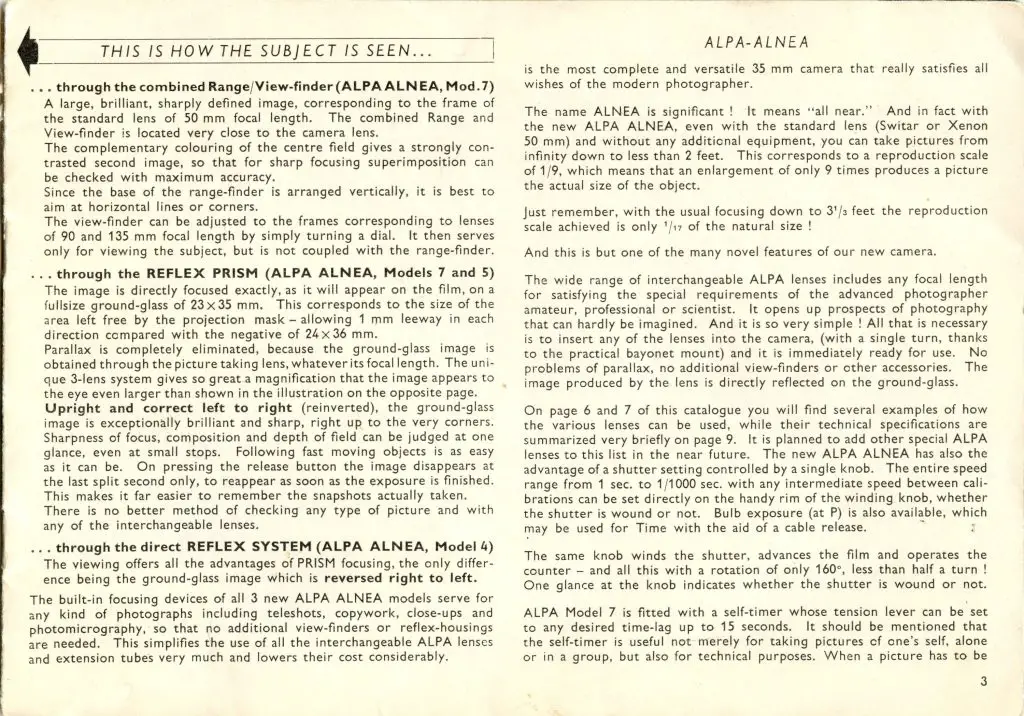

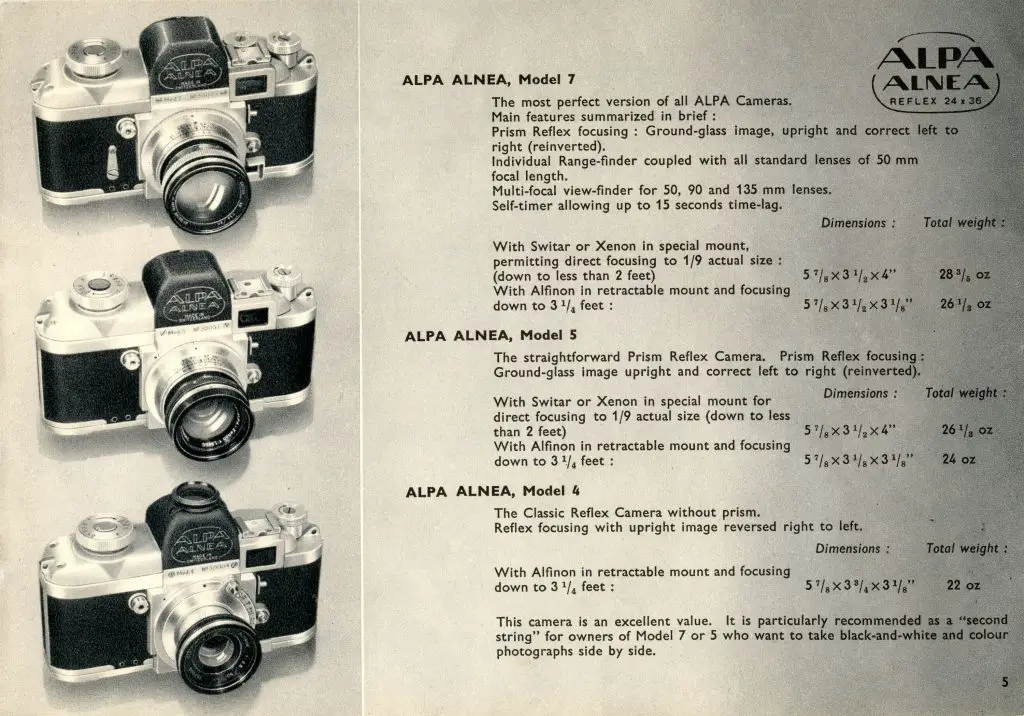

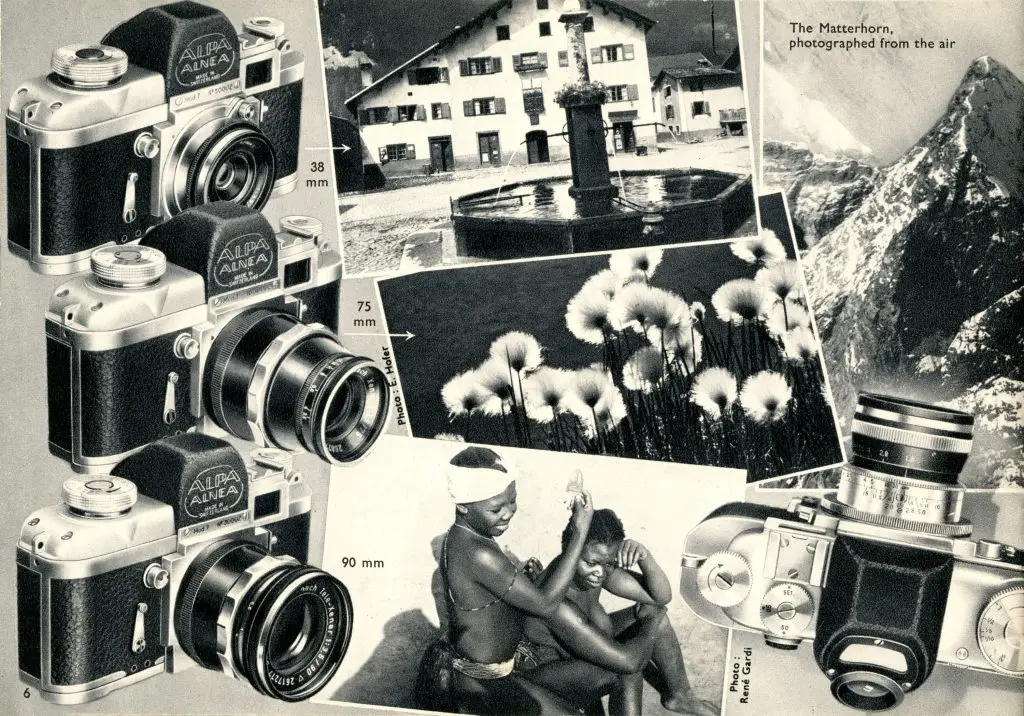

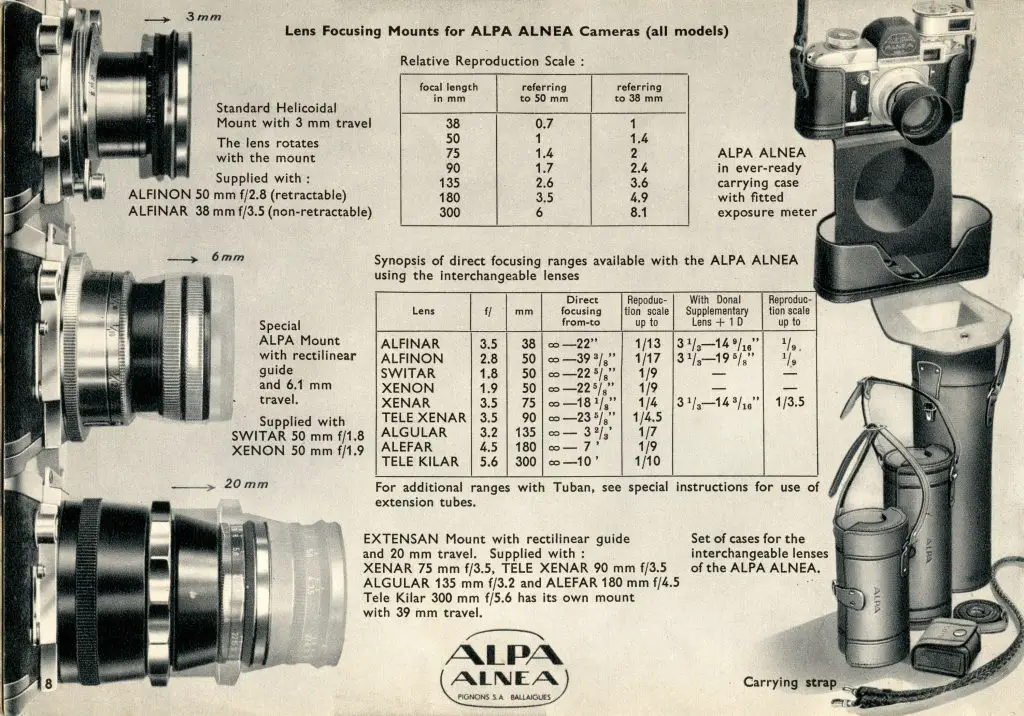

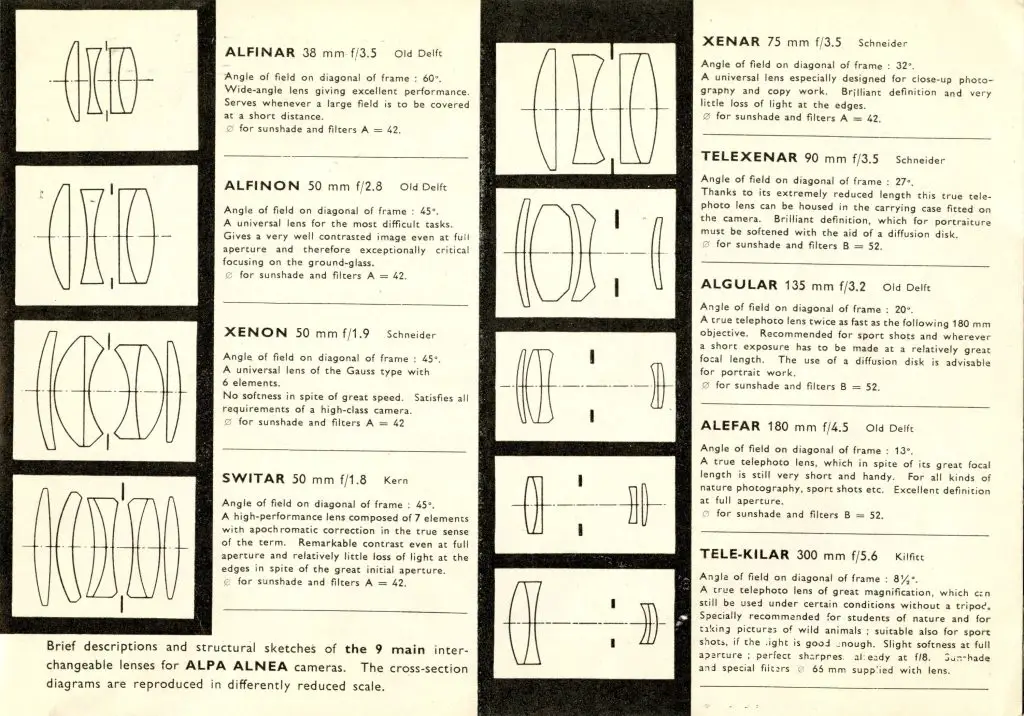

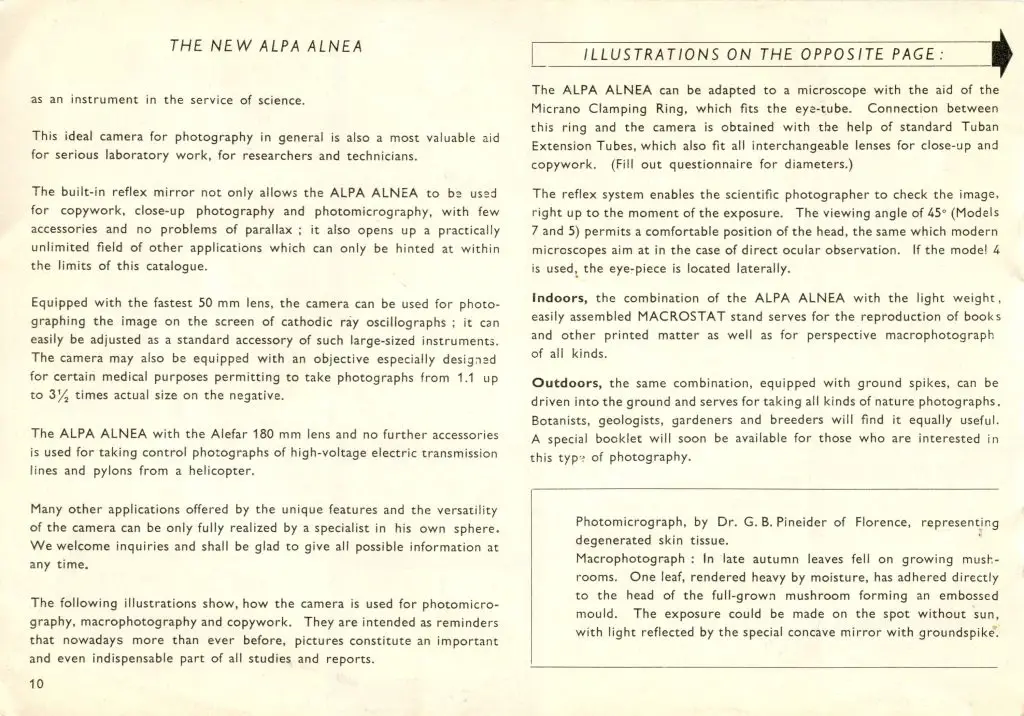

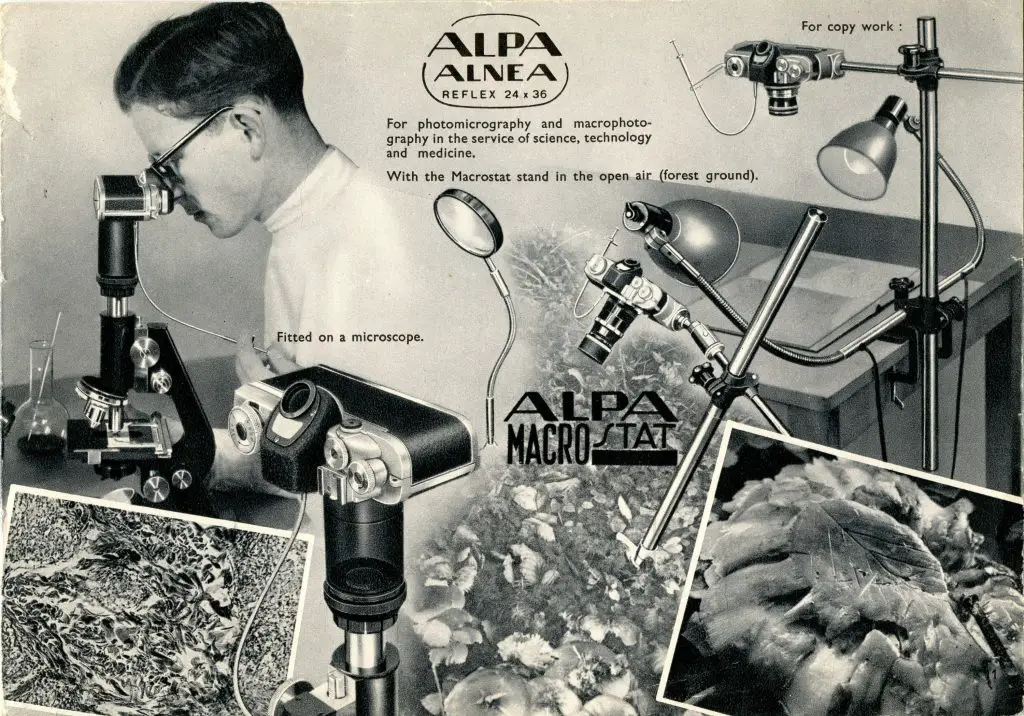

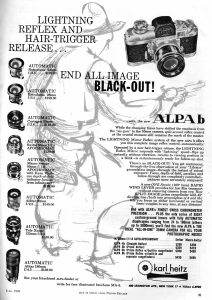

The following gallery is of a promotional pamphlet for the first three models of the Alpa’s second generation. It promotes the Alpas 4, 5, and 7 showing the differences between the two, along with a gallery of available lenses and other accessories that were available at the time.

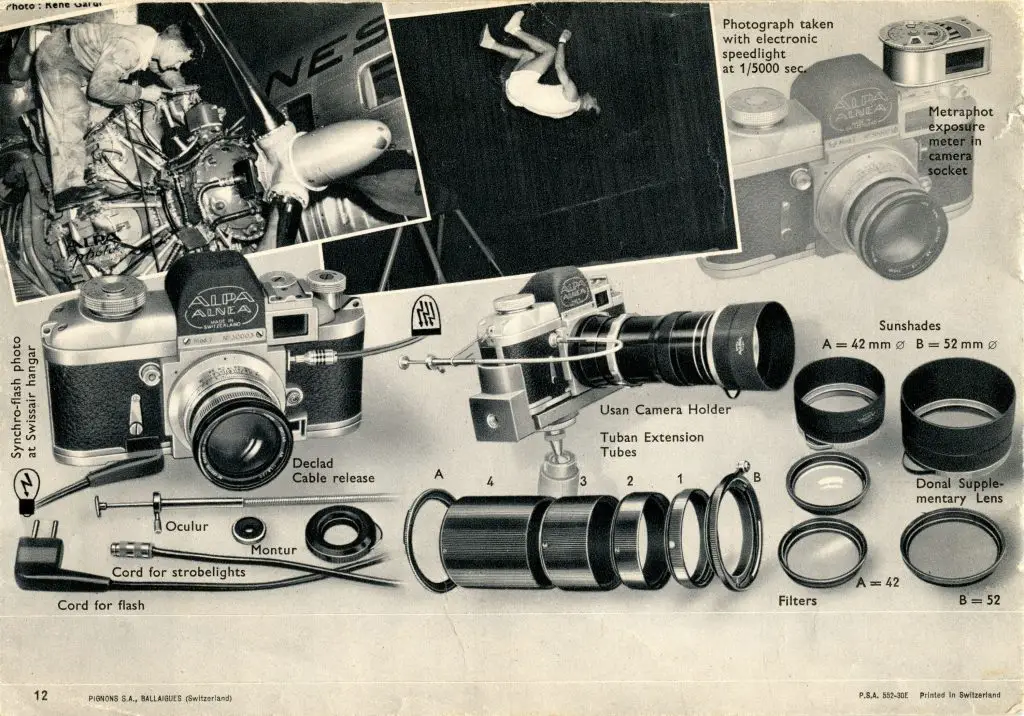

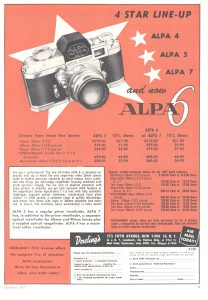

Three models would all debut in 1952, the Models 4, 5, and 7. Alpa Models 6 and 8 would follow shortly after adding a split image focus aide in the pentaprism. All five models of the second generation share a similar body, they mostly vary in their viewfinders. In 1959, all five Alpa models would receive an update to the reflex mirror called the “lightning reflex mirror” in which the mirror works on a hair trigger, instantly flipping up and back down only at the moment of exposure, reducing viewfinder black out. Non-b models still had a mirror that automatically returned, but it moved slowly while the shutter release was being pressed and remain there until pressure on the shutter release was removed. Each of these updated models would have a “b” following the model number.

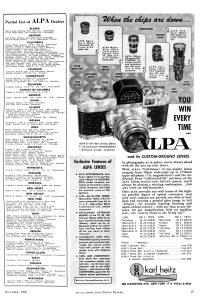

In the United States, Alpa cameras were exclusively imported and sold by Karl Heitz Inc. of New York City and prices ranged from $199 for an Alpa 4 with the base level Alorar 50mm f/3.5 collapsible lens, to $319 for the Alpa 7 with the same lens. The later Alpa 8 would sell for $349. The Alpa 7 reviewed here with the Kern-Switar 50/1.8 lens had a retail price of $469. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $1930, $3100, $3400, and $4550 today, respectively. Putting these prices into perspective, the average American annual salary in 1952 was $3500 a year, a new house was $9050, and a new car was $1700, it is hard to imagine that someone would pay this much for a camera.

A large variety of lenses were available in the Alpa’s bayonet mount from a 24mm wide angle retrofocus all the way up to monster 5000mm telephoto lenses. There were lenses like the Kilfitt-Makro-Kilar D 40mm f/2.8 that had a focus range from infinity all the way down to 2 inches. Some offered automatic diaphragms and others were preset.

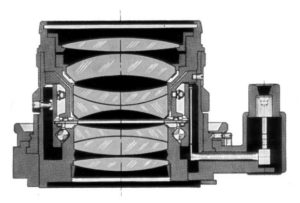

The 7-element Kern Switar 50mm f/1.8 lens was one of the first apochromatic lenses, which means it is color corrected for red, green, and blue for the most accurate color reproduction possible. Most other color corrected lenses of the time only corrected two of the three primary colors of light.

The base lens often seen on most Alpas was a collapsible Alorar 50mm f/3.5 lens which is unique because most SLR cameras do not work with collapsible lenses as the collapsed lens interferes with the reflex mirror. In the Alpa, the mirror is designed in such a way that when collapsing the lens, the mirror is folded out of the way. This feature was eliminated with the “b” models as the new instant return mirror could not be folded back up.

Here are a variety of advertisements by Karl Heitz Inc for Alpa models 4 through 8, that appeared in various magazines in the 1950s.

Although expensive, Pignons made every effort to make every part of the camera and its lenses to the highest quality possible. The camera body is made from a lightweight metal alloy and chromium plated to resist corrosion. The body covering is a durable synthetic leather that resists wear much better than real leather, but has a softer and more grippy feel than Vulcanite or other synthetics used on other cameras.

The cameras had many features that were missing from competitor’s models.

This review from the February 1958 issue of Modern Photography is for the Alpa Model 6 which differs from the 7 in that it includes a split image focus aide in the pentaprism viewfinder and lacks the in-body rangefinder. Otherwise the two models are the same, and many of the author’s observations apply to both models.

Each of the five models from the second generation were produced until 1960 with the release of the Alpa 6c. A third generation camera, the Alpa 6c had yet another new body that replaced the 45 degree pentaprism with a more common eye-level pentaprism, removed the rangefinder and optical viewfinders, and added a selenium exposure meter.

Feeling the pressure of increasingly mass produced cameras, by the mid 1970s, Pignons was struggling to stay profitable. In an attempt to diversify their product offerings, they would partner with the Japanese company Chinon and in 1976 release the Alpa Si series. First using the M42 screw mount and then eventually the Pentax K-mount, the Si-series was said to be built to a higher standard than the Chinon CE II and CE-4 cameras they were based off, but are otherwise unrelated (except by name) to earlier Alpas.

Despite making cameras that were extremely expensive and in very low numbers, Pignons continued releasing new Alpa models until the Alpa 11 series that was in production into the early 1980s. Eventually however, the company succumbed to the ever growing pressure of automation, and by 1990, had filed for bankruptcy.

The Alpa trademark lingered for a couple of years, and then in 1996 was acquired by Capaul & Weber of Zurich, and eventually a new type of premium format Alpa camera was released called the Alpa 12-series which is still made today.

Today, Alpa cameras are some of the most collectible of any ever made by any company. There are those who specifically collect Alpa cameras and no others. Their uniqueness, high quality, and low production numbers make them quite appealing to collectors who are tired of the same old Leicas and Nikons that are commonly sought after. Of course, their rarity also makes them expensive with the cheapest models in the range of several hundred dollars, to some fetching close to 5 figures. This was a brand of camera I never imagined I would get to see in person, let alone own, so having one is quite the honor.

My Thoughts

Back on September 27, 2018 (my birthday), I published Keppler’s Vault 21, which was a review of the Alpa Reflex 6c from the February/March 1962 issue of Camera 35 magazine. In that article, I stated that I’d likely never get a chance to shoot with one as Alpa cameras of any age generally sell at a price that are “unobtanium” to me.

Perhaps publishing that on my birthday caused a ripple in the universe as not even a month after that, while browsing through a local estate sale, I saw what looked to be an Alpa camera sitting on the bottom of a shelf in one of the images. After contacting the seller, I arranged to meet him to view the camera. To my surprise, not only was the camera in fact an Alpa, but it came with 3 lenses, a whole bunch of filters, the case, and some literature. And if that wasn’t enough, they also had a really nice Bolseyflex TLR there as well. Whoever these cameras belonged to, surely had a appreciation for Jacques Bolsey!

I made an offer to the seller to buy the whole lot of cameras at a price I was happy with and took it home. The camera’s shutter was inoperable as the second curtain would never close, but I was still happy. Here was a camera I never thought I would ever have a chance to hold, let alone own. I figured I would display it on a shelf for a while, maybe write about it in a Cameras of the Dead article, and possibly sell it off to another collector at some point in the future.

Then one day after playing with the camera, I noticed the shutter started becoming more and more responsive. I cycled it a number of times and soon that second curtain began closing at what seemed to be the correct speeds. Could it be the camera was working? It would seem that all this vintage mechanical wonder needed was some exercise as it had sat on a shelf for too long. As soon as I felt pretty good about its operating condition, I loaded in some film and took it out shooting!

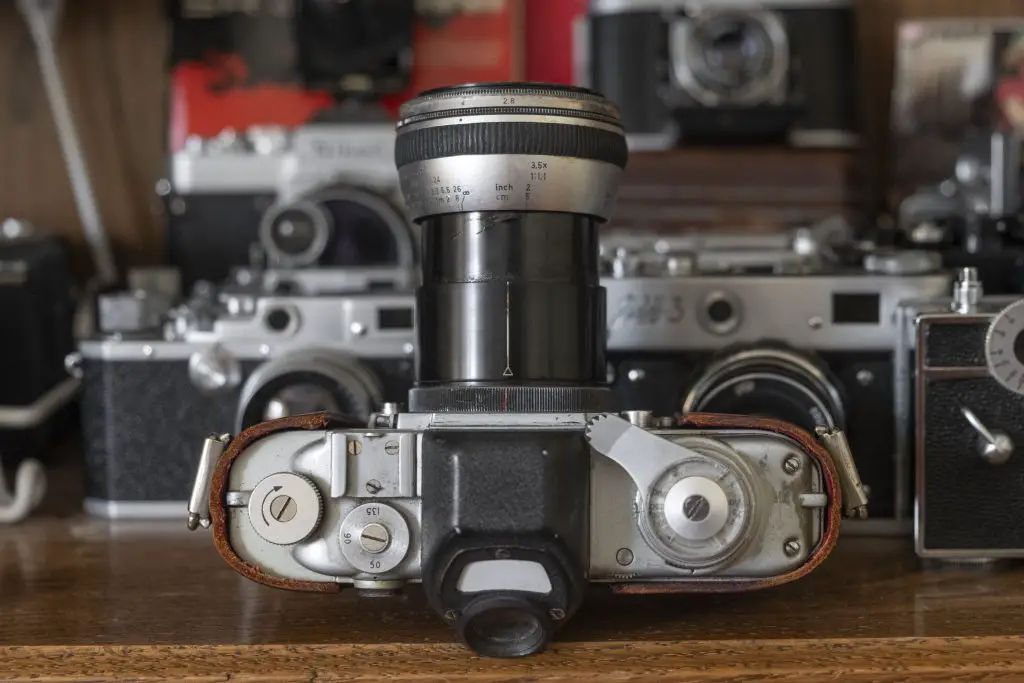

There is a lot going on with the top plate of the Alpa. From left to right is the rewind knob, accessory shoe, and focal distance switch for the rangefinder. The Alpa has a built in rotating prism within the rangefinder’s viewfinder that can be rotated to give a 50mm, 90mm, or 135mm view. When rotating this knob, the entire view through the rangefinder shows the correct focal length similar to many of Canon’s rangefinders. There are no projected frame lines like on other rangefinder cameras.

Next is the pentaprism, which I’ll talk about later, but next to that is the combined shutter speed and film advance knob. Film advance is accomplished with a relatively short 160 degree turn of the knob. This is much faster than other 35mm rangefinders or SLRs of the era that required significantly longer turns, or in some cases, a double turn.

Mounted on top of the film advance knob is an accessory lever which is designed to face forward like in the image to the right. This was a common accessory that I’ve seen on many Alpas, but was not a factory included option on the Alpa 7. Its forward facing orientation looks awkward but is actually quite comfortable to use with your right index finger.

The available shutter speeds are seen through a plastic window on the lever which on this example shows signs of aging making the numbers a bit difficult to read. I’ve thought on many occasions about removing this lever to see the numbers easier, but I haven’t done it yet.

To change shutter speeds, you must push down on the knurled outer ring and rotate it either left or right until the black notch lines up with whatever speed you desire. The shutter speed dial has indicated speeds from 1 – 1/1000 second plus Bulb, which is indicated by the letter “P”, but unmarked intermediate speeds such as 1/40 and 1/80 can be set as well. Beneath the shutter speed selector is the exposure counter which must be reset using the saw-tooth wheel next to it.

Caution: The shutter dial rotates back to its original position when firing the shutter. It is really important not to obstruct this motion when shooting the camera as it will not only slow down the shutter, throwing off your exposure, but it may also cause damage to the shutter!

The bottom of the camera has the rewind button, two raised feet on either side, and a centrally located door lock that when folded out and turned 45 degrees unlocks the back and bottom of the camera. In the center of the door lock is a 1/4″ standard tripod socket.

With the back of the camera off, there is a rather ordinary looking film compartment. For all of the uniqueness of the Alpa, this is one of the few areas of the camera where Pignons didn’t deviate from the status quo. Film loads from left to right onto a removable single slotted take up spool. The spool is removable to support the use of AGFA “Karat” cassettes which transport from cassette to cassette. To remove the spool, you must pull down on a metal tab which holds it into place from the bottom.

The Alpa’s second generation lens mount is a bayonet design unique to Alpa cameras starting with the Alpa 4, and is not compatible with first generation Alpa bodies. The release button is at the 3 o’clock position of the lens mount and must be pressed in while rotating the lens counterclockwise. Installation of a new lens is is the opposite. Some lenses, like the Kern-Switar 50/1.8 seen here support an automatic diaphragm which will stop down the iris to the chosen f/stop using an external coupling that rests in front of the shutter release button. This was a common feature on other early SLRs like the Ihagee Exakta, Miranda SLR, and KMZ Start.

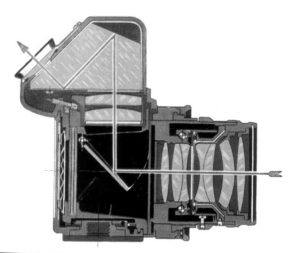

Moving onto what I think is the most peculiar feature of the Alpa 7, is the 45 degree angled pentaprism viewfinder. It works basically like any other pentaprism, except at a different angle. The Alpa’s manual claims that this position is more convenient, but they never say under which circumstances it becomes convenient as it feels a little strange holding the camera horizontally, but when turning the camera vertically to get portrait shots, is downright frustrating.

I found the whole design difficult to get used to as it is neither a waist level, or an eye level viewfinder. I referred to it once as a “neck level” viewfinder as that’s about where you’ll end up holding it most of the time. When holding the camera vertically, you have to position the camera at a 45 degree angle to the subject you are trying to shoot. More than a few times, I would instinctively put the camera up to my face like a normal SLR, only to be reminded to lower it. This slowed me down considerably while shooting, and while I think that after time, I might get more used to it, but clearly not everyone did as Pignons later abandoned this 45 degree design with the Alpa 6c.

Above the viewfinder is a white piece of plastic that is allows the photographer to write what type of film is in the camera. The user manual suggests using a ball point pen and wiping it off with your finger.

Looking through the viewfinder, the image is surprisingly bright for an early SLR. It doesn’t compare to laser cut Fresnel viewfinders of the 70s and 80s, but it worked quite well for me. The viewfinder screen is entirely made of ground glass and there are no focus aides like a split image rangefinder or microprism circle, but there is an engraved plus sign with a two notches sticking out of it. According to the Alpa’s manual, the size of the markings are supposed to help with the reproduction ratio of the exposed image, but I didn’t quite understand it. I don’t think it is necessary for normal use. The user manual also suggests that the image seen through the ground glass is a 23mm x 35mm image. This means the horizontal and vertical image is intentionally cut off by 1mm to account for the cut off from the mask on projection mounted transparencies.

But wait, there’s more! If for whatever reason, the through the lens reflex viewfinder is not enough for you, the Alpa 7 also has a rangefinder! But not just any rangefinder, you see, this one is a vertical viewfinder in which the coincident image moves up and down, rather than side to side. If you don’t like the vertical alignment, you can alternatively rotate the camera 90 degrees and use the rangefinder to achieve focus horizontally. In use, the rangefinder works the same as any other rangefinder, with the notable exception being that the lower window is in a position most everyone will always keep their right hand, blocking the window. In order to use the rangefinder effectively, special care must be taken to hold the camera in a way that doesn’t block this window.

In order to use the rangefinder, you must use a lens that is designed for it. The dial on the top plate of the camera adjusts the rangefinder to show only focal lengths 50mm, 90mm, and 135mm. If you use a lens with a focal length other than that, or one that’s not designed to couple with the camera’s rangefinder, the rangefinder patch will disappear entirely, giving you a straight through optical viewfinder. This is a nice touch that I haven’t seen on other rangefinder cameras.

The viewfinder window is very small, about the size of the earliest Kodak Retinas, and although I made an attempt to capture an image looking through it, I couldn’t get my camera close enough to get a good image so here’s an illustration from the Alpa’s manual to the right. At first glance, it looks like any normal coincident image rangefinder with a small square sized image through a second window projected in the center. Where the Alpa’s rangefinder differs is that instead of the image moving side to side, it moves up and down, due to the orientation of the rangefinder windows on the front of the camera.

For photographers wishing to use flashes, the Alpa supports both flashbulb sync at every shutter speed via a two pin “Kalart-Graflex” connector below the self-timer lever. Electronic (X-sync) is available using a second flash connector on the side of the mirror box, below the in-body rangefinder window at shutter speeds of 1/25 or 1/50.

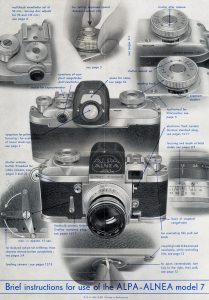

Pignons clearly made a great effort to make the Alpa to be as great of a camera as they could, but that greatness extends beyond the camera. Alpa cameras and their accessories all came in nicely designed red boxes as seen in several of the images above. Even the user’s manual was well thought out. I was fortunate to receive an original copy of the manual with this Alpa 7 and it is printed on high quality paper with a thick card stock cover to protect it. At the end of the manual is a four page fold out quick reference guide that I have scanned and included to the right. I found this guide to be immensely helpful in quickly learning the camera’s basic functions, and that it is physically part of the user manual means it won’t easily get lost like many single page cheat sheets.

Pignons clearly made a great effort to make the Alpa to be as great of a camera as they could, but that greatness extends beyond the camera. Alpa cameras and their accessories all came in nicely designed red boxes as seen in several of the images above. Even the user’s manual was well thought out. I was fortunate to receive an original copy of the manual with this Alpa 7 and it is printed on high quality paper with a thick card stock cover to protect it. At the end of the manual is a four page fold out quick reference guide that I have scanned and included to the right. I found this guide to be immensely helpful in quickly learning the camera’s basic functions, and that it is physically part of the user manual means it won’t easily get lost like many single page cheat sheets.

For a company like Pignons with no camera making experience, their ability to produce such a high quality and precise camera with so many state of the art features was quite an accomplishment. In addition, the camera is gorgeous. I love the crinkle paint finish of the pentaprism and lens shades, the soft curves of the top plate and other areas of the camera are a nice alternative to the angled styling tradition that would become a cornerstone of Japanese SLRs in the years to come.

While preparing for this review, I took many more photos of the camera than I can possibly discuss without repeating myself, so below is a gallery of all the extra images that I took for your viewing pleasure.

Overall, the Alpa 7 handles quite nice. The body is surprisingly lightweight at only 656 grams without a lens. Considering its age, and the heft of early SLR cameras, the Alpa would be much more comfortable if left hanging from a neck strap for longer periods of time.

The body of mine had a sort of yellowish brown patina to it that didn’t easily wipe off. When I first saw it, I thought it might be dried up gunk from years of use, but after seeing a few other Alpas with a similar yellowing, I’m starting to think that its some kind of clear coat that was originally applied on the body that’s wearing off. Whatever it is, it gives a nice “patina” to the camera so I left it alone.

Kamerabau-Anstalt-Vaduz Kilfitt-Makro Kilar D 4cm f/2.8

It is rare for me to ever have much of any significance to say about a specific lens as I really don’t have the knowledge, resources, or eyesight to give meaningful lens reviews.

With the Alpa 7 came three lenses, one of which was this lens with a mouthful of a name, the Kamerabau-Anstalt-Vaduz Kilfitt-Makro Kilar D 4cm f/2.8. There were two versions of this lens available, the D, and the E with the only difference being that the D version had a minimum focus of 2 inches (1:1.1 reproduction ratio), and the E was “only” 4 inches (1:2). Stop and think about that for a moment. A lens that can focus from infinity down to 2 inches, without any special attachments, close focusing filters, or extensions. On top of that, this was no gimmick lens as it was very high quality.

The Kilfitt-Makro-Kilar was designed by prolific camera and optical designer Heinz Kilfitt in München, Germany, but was built in the tiny country of Liechtenstein by Kamerabau-Anstalt-Vaduz. The lens is most often found with an Exakta mount, but also came with mounts for Alpa, Praktina, Mecaflex, Rectaflex, and Pentacon (M42).

Although a relatively simple 4-element compound triplet of Tessar design, it was built to a very high quality and produced excellent images. When it first made its debut in 1955, it had a maximum aperture of f/3.5, but in 1958 was revised to f/2.8. The 40mm focal length was likely chosen to keep the lens small, since the large helical would need a lot of space to accommodate the wide range of focus distances.

With the lens focused to infinity, the lens is relatively compact, looking much like any other prime lens you’ve ever seen, but turn the focus ring down to the minimum focus distance of 2 inches (5 cm), and things get rather “phallic”.

As impressive as this is for a vintage film lens, I was curious to see what it could do on my digital mirrorless, so I promptly ordered an Alpa -> Fuji X-mount adapter on Amazon and mounted it to my Fujifilm X-T20. The sharpness and ease of switching from infinity focus to extreme close-ups was a game changer for me. Especially when it came to shooting the “beauty pics” of the cameras for this site.

Ever since late 2015, I have been using some type of classic film lens for every picture of a camera I’ve reviewed. My thought on this was that although I was shooting digital images, there would be a bit of “street cred” by using a classic film lens. I bounced around between various Nikkor lenses and M42 screw mount lenses, before eventually settling on an Asahi Super-Takumar 55mm f/1.8 lens from my Pentax Sv. Not only is that an incredibly sharp lens, but I liked that it had an “Auto/Man” switch that allowed me to flick the lens between wide open for sharp focusing, but also to stop it down quickly for shots.

I used to shoot a Nikon D7000 DSLR which when using an M42 lens, loses infinity focus, but gives a slight macro effect. But sometimes I wanted to get closer, and for that, I’d have to keep switching M42 extension tubes. With the X-T20, I overcame this with an M42 Helicoid adapter that allowed me to get closeups without having to use extension tubes, but it wasn’t elegant as I’d have to switch between the lens’s focus ring and the helicoid’s ring.

With the Makro-Kilar, I found the perfect compromise as I could focus as close as I wanted with a single focusing ring. Not only that, but the slightly wider 40mm focal length improved depth of field compared to the 55mm length on the Takumar. Both my Nikon D7000 and Fujifilm X-T20 cameras use APS-C crop sensors which multiply the focal length by 1.5x, but still, a 60mm focal length is easier to work with than 82.5mm.

Upon seeing the first results from my Alpa to Fuji lens combination, I was immediately impressed and that lens has since become my go to lens for camera beauty shots. Any review that I’ve posted on this site where I took the pictures from roughly September 2018 or later have been shot with the Makro-Kilar. It is a perfect classic lens and camera combination and meets all of my needs. Here are a couple of sample shots done with this lens and camera combination, but if you want to see more, almost every review I’ve posted in the past 6+ months has images shot with this lens.

My Results

Although this camera started working in the winter of 2019, I wanted to wait until colors started to return in early spring, so I kept the camera sitting idle until it warmed up outside. Waiting was very difficult as every time I went into my camera room, I saw it sitting there on the shelf…looking back at me….taunting me….oh, the horror!

Painful as it was, the cold grip of winter eventually relented and I was able to load up the Alpa with some fresh Fuji 200 and took her out shooting. I would shoot most of the roll with the 50mm f/1.8 Kern-Switar lens, but for the closeups, I tried the 40mm f/2.8 Kilfitt-Makro Kilar lens for its minimum 2 inches focusing distance.

The Alpa and its lenses came with quite a positive reputation, so I had pretty high expectations for the images it might make. The biggest variable of course was how well the camera functioned. The shutter wasn’t working when I first acquired the camera, and I made no attempt at replacing light seals or anything to keep light leaks out.

I was pleased to see that the images from my first roll came out quite nice. Alpas have a reputation as one of the most desirable cameras to collect, but I have my doubts as to how many of these collectors actually use their cameras for their intended purpose, so to see properly exposed and sharp photos on my negatives as they were drying, I was doubly pleased.

What I am about to say next I may one day regret, but if you know one thing about me, it is that I get enjoyment from shooting any camera, from a lowly box camera, to an Argus C3, a Nikon SLR, to prestige cameras like this. The reality of the matter is, cameras like the Alpa 7 are a luxury item in the same vein as a Rolex watch, a Bentley automobile, or a set of Bang & Olufsen speakers. Yeah, each of those brands is well known for their quality, reliability, and prestige, but you’ll keep the same time with a Casio watch, or get groceries just as easily with a Chevy, or hear the latest Cradle of Filth record with a set of JBL speakers.

I really like the Alpa, and am absolutely thrilled to have it in my collection, but none of these images look any better than dozens of other, much less expensive cameras in my collection. Perhaps those collectors with the deep pockets that have shelf after shelf of Alpas but never use them are smarter than me. These are precision instruments, works of art even, and as cameras, they’re terrific, but who wants to get caught in a rain storm or shoot street photography on the south side of Chicago with a $2000 Alpa?

With that in mind, it is impressive to me at the level of innovation and attention to detail with this camera. I didn’t love the 45 degree angled viewfinder, but Pignons was doing something that not many other people were doing in 1949 when they put a similar prism on the Alpa Prisma-Reflex. This was uncharted territory, and the idea that you could have the benefits of both a rangefinder and an SLR in the same camera is pretty cool even today.

The Alpa is a great camera, perhaps one of the greatest cameras I’ve ever used, even. But a great camera is not always necessary to make great images. If you’re looking to add an Alpa (or any prestige camera for that matter) to your shelves, make sure you are honest with yourself about what you plan on doing with it as it seems that’s where most of these wind up. Interestingly, during my research for this review, I found very little information in the way of user reviews. It seems there aren’t too many people shooting these cameras anymore.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Alpa_Alnea_7

http://web.archive.org/web/20160807214509/http://www.alpareflex.com/Cameras/index.html (Archived)

https://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=160094

http://www.brennanprobst.com/2017/05/spotlight-alpa-alnea-model-5.html

Thank you for this story! Alpa is one of those marques we filmosaurs of limited means have dreamed of owning for decades, while realizing that there’ll never be sufficient funds in the GAS account to buy and CLA one. This article is the next best thing.

.

The Macro-Switar is well-known to Exakta users, considered likely the best macro lens ever made for that camera. And examples of this lens with the Exakta bayonet mount are affordable … sort of.

Thanks for the compliments, Roger. Despite my comments about the Alpa being a prestige camera, let me assure you, that Makro-Kilar is not. If you never become fortunate enough to find one for an affordable price, I will tell you the Makro-Kilar, in any mount is worth it. Alpa, Exakta, M42, or whatever mount you can find it in, buy it and then get whatever adapter you need to shoot it digitally.

I love shooting digital images with this lens, and have even gone back and reshot some “beauty” pics of cameras that I had previously shot with the Takumar.

Oh, am I jealous, Mike! A working body and three lenses, one of which is the Kern Macro Switar. I could afford an Alpa body at entry level, they’re cheaper than a lot of M Leicas, but then the cost rockets with the lenses, so just another dream.

By the way, when shooting macro, the actual focal length is less important in determining depth of field. The “law” applies if you shoot at the same distances with other lenses, but then the shorter focal length produces a smaller image. With macro shots, DoF is related to the reproduction ratio and provided the same aperture is used. So if we assume 1:4 the image will be the same size on the film/sensor irrespective of the focal length length of the lens used.

In practical use, then, if you shoot your camera collection with different focal length lenses, but you frame so the subject is the same size, there may be no advantage in using shorter focal lengths. In fact, you may well find perspective distortion rears its head.

Thanks for the clarification with depth of field on macro lenses. I’ll admit to not doing much with macro photography. Even when I use macro lenses, I typically don’t get in all that close, as I mainly use them for getting in that 12-15 inch range for product and camera photography.

I mentioned this to Roger that while the Alpa camera is really neat, that Makro-Kilar lens is awesome on digital. My advice is to find one on whatever mount you can and just get an appropriate adapter to use it. You won’t be disappointed!

On your head be it, Mike. I’ve just splashed out on a D f2.8 version in Exakta mount. I’ve got Fuji/Sony Exakta adapters for digital, so I’ll be up and running soon, depending upon how long it takes to arrive from Poland.

Nice article about my favorite camera, the Alpa Alnea 7. I purchased mine two years ago. Rarely do I use a digital camera now. I like the size and the slowness of using this camera. To get a good focus I first use the range finder then move to the ground glass (especially in dim lighting situations) . I take this camera to live music shows in Europe and Chicago. The 45 degree prism is a viewing aid. I can hold the camera upside down. By looking up into the prism I can see over the people in front of me. With the Nikon, 42mm and Exacta lens adapters I have a wide range of lenses to use with this camera. I started carrying the camera in my coat pocket. With the Old Delft 50mm f2.8 I am able to collapse the lens into the camera body and maintain the functionality of range finder focusing.

Thanks for the feedback! I am glad you enjoyed the article about your favorite camera. I was really in love with the Alpa and enjoyed using it, although the 45 degree viewfinder did take some getting used to. Sadly, it’s not a camera I’ve come back to since writing this article, but I’d be willing to bet that in time I could learn to appreciate it as much as you!

Finding a killer deal like yours is every gearhead/collector’s dream. I’m more than a little envious.

Alas, I’ll have to be content with reading your review and dreaming on. Thank you for all the hard work that is reflected on these articles.

Mike, hi from Australia.

Many thanks for your article on Alpas, specifically the Alnea 7 – well researched & written

I was lucky enough to pick up an Alnea 7 with Kern-Switar 50 & lens hood/case etc a couple of years ago on Gumtree here. Still in lovely condition & totally functional except for a few small bugs. I also managed to make contact with someone in Switzerland who has supplied me with new/OS filters plus he has access to the factory documentation for each individual camera made – he’ll send you a PDF (for a very small fee) of your camera’s details – when made, inspected & shipped to the relevant country etc.

Cheers & keep up the good work

Stephen

Thanks for the kind words Stephen! Someone else also alerted me to the gentleman who has all the Alpa records and I might have taken him up on getting the records for the Model 7 I reviewed, but since posting this review, I ended up selling the camera. As much as I like the look and feel of the camera, I did not enjoy shooting it enough that it was worth it to keep such a high value camera sitting on my shelf. I sold it and used the money to buy other cameras which I’ve written reviews for!

Awesome review and a cool camera!

Hey Mike, very nice review, I now have two Alpa 7’s plus the 40mm f/2.8 Kilfitt-Makro Kilar D and Switar lenses I try and use all my Alpa’s from time to time. I also have a 6b, 9d and 10d.

I won’t say that I prefer them over the Leica’s, but they are very solid and well built. I actually like the viewfinder and my images from the Kilfitt and Switar have that Je ne sais quoi

Thanks for all you do

Hi Mike. An interesting article, I must say. I am currently on my third Alpa-a 6b-having previously owned a 6c and a 9d and no, it doesn’t sit on a shelf being looked at, it gets used on a regular basis .By regularly, I mean pretty much weekly and using it as Pignons intended ,i.e to take pictures with. All of the second generation Alpas do seem to discolour but seemingly to random and unusual shades. Mine has gone almost a feint (and strangely pleasing) mint green. The Kern Switar is a special lens-damn sharp and renders beautifully on B&W. Not the easiest cameras to shoot with but so much more interesting than other high end cameras of its ilk. I got a little bored of being constantly stopped and asked whenever I’ve used a Leica M of some description. Nobody does that when I’m out with the Alpa. People just think it’s some weird old contraption in my hands, and leave me alone!

That’s good to know about the discoloration. I always assumed it was some type of clear coat, or shellac that they applied over the bodies to protect them. Over time, age, UV light, etc, it probably changes color. I have no proof of this, but that’s what I always guessed.

I have to laugh though that you got more attention with a Leica M than an Alpa. For me, it would be the opposite! 🙂

The main problem with the Alpa bodies is that it’s near impossible to find anyone to carry out servicing, never mind repairs. Alpa bodies were mainly serviced and repaired at the factory service department so technicians were not trained outside of this facility.

There is a very good reason why collectors don’t use the cameras: they are afraid of them breaking down. Then the value would doubtless plunge!

To use, for the sheer pleasure of using a top quality non-Japanese vintage camera, one simply cannot beat the first Leicaflex. Made 1964-68, every bit as quirky looking, the range of lenses far exceeds Alpa. Indeed, Schneider of Kreuchnach and Angenieux both made lenses for the two marques. The best known is the P.A. Curtagon 35mm f4 Perspective Control lens, made with different mounts including Alpa and Leicaflex.

I’ve used a very early (1964) Leicaflex with the Schneider Curtagon 35mm f4 lens for several years. Taken it with me time and again. Although the meter in my camera works, there is no coupling between the lens and body so I leave the battery out and use a trusty Gossen Lunalite.

This takes the readily sourced PP3 9v battery that’s even available in my rural village post office here in England. A considerable advantage of the Lunalite is the readout: three red LED’s. Unlike a needle pivoted between two points and easily dislodged by shock, the solid state readout is far more rugged and better for travel.

The quality of finish is amazing on the Leicaflex and the level of detail never ceases to impress me.

Perhaps the reviewer might like to seek out a combination like mine and give us his views. I’m sure he would not wish to part with this superb kit (meter).