This is a Canonet 19, a 35mm rangefinder camera built by Canon of Japan starting in January 1961 and sold in the United States by Bell & Howell. When sold with the Bell & Howell name, it was known as the Canonet 19, but when sold by Canon, it was simply the Canonet. The Canonet was the first in a long running series of intermediate fixed lens 35mm rangefinders that would take the place of Canon’s interchangeable lens rangefinders. The Canonet features shutter priority automatic exposure via it’s coupled selenium meter around the 45mm f/1.9 Canon SE lens. It has a coupled coincident image rangefinder with meter readout in the display, and has a bottom trigger film advance lever. Despite being sold as a lower cost option to Canon’s earlier cameras, the Canonet series would prove to be very popular and well regarded cameras, leading the industry in the fixed lens rangefinder segment.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/1.9 Canon SE coated 5-elements in 4-groups

Focus: 2.6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder, 0.67x Magnification

Shutter: Copal SV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ viewfinder exposure display and Shutter Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold Shoe with PC socket M/X Flash Sync

Other Features: Bottom Trigger Film Advance, Self-Timer

Weight: 746 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/canon_pdf/canonet.pdf

How these ratings work |

Canon nailed it on their first attempt at a fixed lens rangefinder. The original Canonet 19 had an excellent lens, large and bright viewfinder, shutter priority auto exposure, a fast bottom trigger film advance, and very good build quality. Later Canonets seems to be more desirable by collectors because of their smaller size, but they also increase the use of plastic and electronics that can fail. Even with a dead meter, the Canonet still works 100% mechanically, making it an excellent option today for the collector and shooter. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for the complete package, an excellent camera with an excellent lens and nothing to dislike | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

History

In the early 1960s, Canon was at the top of the Japanese Camera Industry, which between the years 1950 to 1956 saw annual sales nearly quadruple from $2.3 million to $7.1 million, and in the four years after that, nearly double again. Canon went from a small shop opened by three men in the mid 1930s to a curious maker of Leica copies, to a company whose interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder cameras rivaled, or in some instances, exceeded those made by reputable German camera makers. The Canon P from 1959 sold almost 88,000 copies, topping all other Japanese Leica Thread Mount cameras by a wide margin. Canon’s next model, the Canon 7 would top even that, selling 137,250 units between June 1962 and November 1964.

Canon’s ability to take a camera that was similar to those sold by countless other Japanese and German companies, improve upon the formula, adding new features, world class lenses, all while keeping prices affordable meant that if you were in the market for an interchangeable lens rangefinder at this time, you at least strongly considered a Canon.

Canon’s ability to take a camera that was similar to those sold by countless other Japanese and German companies, improve upon the formula, adding new features, world class lenses, all while keeping prices affordable meant that if you were in the market for an interchangeable lens rangefinder at this time, you at least strongly considered a Canon.

If there was one downside to Canon’s dominance in this market, is that by the early 60s, the buying preferences of it’s customers were slowly moving away from interchangeable lens rangefinders. The dawn of the Single Lens Reflex had already arrived, as did that of simple “electric eye” cameras which automated exposure, making photography easier and more accessible to novice photographers than ever before. Sure Canon’s cameras were great, but more and more people found that you didn’t need a great camera to make great images.

Things were not all perfect at Canon however. The 1959 release of the Canonflex SLR was the company’s first misstep and would set the trajectory of the company for the next couple of decades. The Canonflex was designed to compete in the same market as Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon Reflex, however Canon miscalculated what photographers wanted in a top tier SLR and the camera sold poorly.

Soon after it’s release, simplified versions of the Canonflex called the RP and RM were released, which both had fixed prisms, and in the case of the RM also removed the bottom trigger film advance, but added a coupled exposure meter to the top plate.

Perhaps realizing that simpler cameras with more and more automation was where the industry was headed, along with simpler SLRs, Canon also looked to simplify it’s 35mm rangefinder lineup with an all new series of fixed lens rangefinders which they would call the Canonet. The first Canonet would make it’s debut in 1961 with the company’s first ever implementation of auto exposure via a coupled selenium exposure meter.

Although lacking an interchangeable lens, the lens it did have was an excellent 5-element 45mm f/1.9 design new to this camera. The build quality of the Canonet was superb, and Canon’s execution of shutter priority automatic exposure was well implemented. The camera was up to Canon’s usual quality standards and featured the company’s preference for bottom trigger film advances.

The camera was heavily hyped prior to it’s release, namely due to Canon’s promise that the camera would debut for under ¥20,000, a price point that was unheard of for such an advanced camera. Many assumed Canon would not stick to this promise as there would be no way for the company to profit from it, but they did, and when the camera first went on sale in January 1961, the camera sold extremely well. A story I found online says that at Mitsukoshi’s Nihonbashi department store in central Tokyo, the Canonet sold out in two hours.

Sales were strong throughout the rest of the year as by November 1961, more than 210,000 units had been produced, and the one million mark was reached in July 1963. This further proved to Canon that competing at the top of the market wasn’t a necessity for success as people were willing to spend good money on easy to use, but high quality cameras.

A short test of the Canonet in the May 1961 issue of Modern Photography claimed it to be the first auto exposure camera tested by the magazine that allowed for a full range of shutter speeds, giving proper exposure at 1 second or 1/500. The review praised the streamlined no nonsense design, saying the camera had no added gimmicks. Minor complaints about a lack of contrast from the rangefinder patch in the viewfinder and aperture and focus rings that were too close together were the only cons of the camera. Image quality was praised, as was the camera’s $119.50 retail price, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to just under $1200 today.

In the 1950, like all Japanese optics companies, Canon struggled to get their products in American stores. Distribution agreements with local distributors like C.R. Skinner in San Francisco and Scopus Inc, in New York opened the door on the coasts, but sales of Canon products in the Midwest were almost non existent.

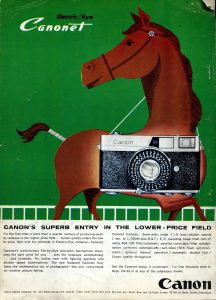

In 1961, to help boost the brands awareness all over the country, Canon would reach an agreement with Chicago based Bell & Howell to distribute cameras in American photo stores. The first camera distributed under this agreement was the Canonet, which when sold under the Bell & Howell name, was known as the Canonet 19, rather than just the Canonet.

This arrangement would be beneficial to both companies as it opened the door to many more retailers than Canon previously had access to, but for Bell & Howell, who did not have much of a presence in the 35mm market, offered them the opportunity to sell more products in this segment.

A complete understanding of the agreement between Canon and Bell & Howell is not clear, as it appears that Canon was still able to use other distributors on the east and west coast. It is plausible that Bell & Howell only distributed in the Midwest and left the coasts to other distributors, but that is only a guess.

What is clear is that some of Canon’s products such as the Canonet, Canon 7, Canonflex RM, Canon FD, Dial 35, and a few others were co-branded Bell & Howell / Canon, and a couple models like the Bell & Howell Auto 35 Reflex and Bell & Howell Autoload 342 were Bell & Howell only. The presence of the Bell & Howell name was purely cosmetic as no functional changes were ever made to any of the models.

The arrangement between Canon and Bell & Howell would last through 1976, at which time Canon was a big enough name in the US marketplace, that piggybacking on someone else’s reputation was likely no longer needed.

As for the Canonet, a less expensive alternative to more professional interchangeable lens rangefinders and SLRs was hugely popular and spawned a whole series of Canonet rangefinders that would be produced until 1978. The first new model in the Canonet series was the Junior from 1963. A simplified model only offering full automatic control, scale focus, and a more compact body, the Canonet Junior was the company’s least expensive camera at the time. An updated model called the Canonet S replaced the selenium meter of the original model with a CdS meter that was more reliable and had a wider sensitivity range.

Other highlights of the series were the Canonet QL19 and QL17 from 1965 which debuted the company’s new “Quick Load” film system in which loading a new roll of film only required extending the leader to a point above the take up spool, and a small metal door would trap the leader upon closing the main film door, securing it to the spool, and the Canonet G-III QL17 from 1972 which came in a much more compact body, with advanced electronics, while still retaining full manual control.

Canon would continue to success well past the last Canonet rangefinders. With models like the Canon F-1, AE-1, and eventually the EOS series, the company would go on to become a technology powerhouse, not only in the optics, but also photocopier, and computer industries. Canon still exists today as one of the biggest camera brands in the world.

Today, it would be hard to find a collector without some Canon cameras in their collection. Whether it’s the original Hansa Canons from the 1930s, to one of their many excellent Leica Thread Mount rangefinders, to their huge catalog of manual and auto focus SLRs, there’s something for everyone. In addition to making great cameras, Canon’s lenses were some of the best as well, as even the company’s modest point and shoot cameras were capable of excellent images, so whatever your reason for seeking out a camera, either to collect, or shoot, there are a huge number of models to choose from.

My Thoughts

Of all the cameras I’ve reviewed, how I come across them usually falls into one of three categories, cameras I wanted and bought, cameras that were loaned to me, and cameras that fell into my lap. In the case of the Canonet 19, this one was in the bottom of a box of cameras I had purchased from KEH a couple of years ago and I didn’t even know it was there. It was one of those “untested” lots that KEH used to sell where they would show 3-4 group shots of a bunch of stuff with no descriptions, and it was up to you to make heads or tails of what it was. This particular lot had a couple interesting cameras that I could see which I wanted, but there were a few things either in cases or not clear enough in the pic to know what it was, but the risk was worth it, so I bought it.

When I finally freed the Canonet from it’s leather and velvet lined prison that it had likely spent the better part of half a century in, I saw a camera that looked barely used. There were no scratches, dings, dust, or anything on the camera, in the lens or the viewfinder. In fact, there’s a chance this camera was never used…which for cameras is actually a bad thing as unused cameras tend to seize up, but after a couple of test shots, everything seemed to be working, even the meter!

If you’ve only ever handled a later Canonet rangefinder such as the superb Canonet G-III QL17, the earlier Canonet 19 is much larger in every dimension and quite a bit heavier. Tipping the scales at 746 grams, the Canonet 19 is 142 grams heavier than the QL17 and 222 grams heavier than the similarly sized Canonet 28. Side by side the later Canonets look like toys in comparison.

The top plate of the Canonet 19 is very clean with an attractive and very stylized “Canonet 19” logo. This typeface is interesting as it was short lived by Canon, only used on the early Canonet models. Interestingly, a Soviet camera called the LOMO Selena Automat was produced around the same time as the Canonet and used the exact same typeface for it’s logo, although the two cameras are unrelated.

In the center is an accessory shoe, most likely for connecting a flash, and to it’s right a large and cable threaded shutter release with collar for timed exposures around it, and the automatic resetting exposure counter.

The bottom of the camera is a bit more interesting featuring the rewind knob with fold out handle, trigger film advance lever, rewind release lever, a 1/4″ tripod socket on a raised foot to help balance the camera when set on a flat surface, and around the tripod socket a small button with lever which is used to unlock and open the film compartment. During the era in which the Canonet 19 was made, Canon was very fond of bottom trigger film advances, using them on many different models such as the VT Deluxe rangefinder and the Canonflex SLR.

Unlike other bottom trigger film advances such as the one used on the Leicavit accessory which are linear, Canon chose an axial system where the motion of moving the lever rotates a shaft, advancing the film. This motion gives the lever somewhat of a curved arc that feels more natural than a lever moving in a straight line. According to Canon, this meant that with practice, speeds of up to 2 exposures per second could be achieved.

In the image to the left, I am holding the Canonet with my right hand, which is opposite of how I would hold it when shooting. I did this to show the open handed position of my fingers as I grip the lever. For anyone whose never held a bottom trigger film advance camera, it is quite natural and comfortable to use. I definitely see the appeal why so many companies invested in this design before battery powered motor drives became standard.

The ergonomics of the trigger also put your right index finger right in front of the focus tab which in the image to the left is directly below the lens. In normal operation, with your left hand on the trigger, it is very easy to focus the lens using your left index finger without having to change the position of your hand, all while still stabilizing the camera.

Around back, there’s little to see. A large rectangular opening for the viewfinder is in the upper left corner, next to an engraving with the camera’s serial number. No other controls are present on the rear of the camera.

Using the lock on the bottom of the camera pops open the right hinged door, revealing the film compartment. Unlike many cameras of it’s era, film transports from right to left onto a fixed and double slotted take up spool. The reason for the reversed film transport is likely due to the mechanics of the film advance being on the bottom, rather the top of the camera.

Otherwise, everything else is as expected. There are twin rails above and below the film gate, the inside of the door has a large painted film pressure plate with divots that help reduce friction as film passes over it, and both a roller and springs to help maintain film flatness. Like most cameras of it’s era, the Canonet uses foam light seal material on the door hinge and in the film channels which is crumbling away and should be replaced before attempting to shoot film in the camera.

Exposure controls for the Canonet are around the shutter, like on most leaf shutter cameras. Closest to the body is the large focus wheel, which as mentioned earlier has a tab that sticks out near the bottom of the camera, in easy reach of the photographer’s left hand while holding the film advance lever. An index mark exists on the front face of the camera which points to the selected distance. A full motion from minimum to infinity focus is very short, only requiring a flick of the finger, however this makes precise focus difficult.

Next, is the aperture control with options from f/1.9 to f/16 plus a red AUTO to put the camera into shutter priority auto exposure. Closes to the front of the lens is the shutter speed control with options from 1/500 to 1 second plus Bulb. It is not possible to put the shutter in Bulb mode with the aperture ring set to AUTO. You must first manually select an f/stop before choosing Bulb.

As seen in the earlier image of the bottom of the camera, a lever on the bottom of the shutter selects the film speed which can be seen through a square window on the side of the shutter. A second lever, the one with a red tip, activates the self timer. As with most half century old leaf shutter cameras, unless your camera has recently been serviced, you should not try to use the self timer as they can easily become stuck, preventing the shutter from working.

The Canonet has a large and bright viewfinder which can easily been used while wearing prescription glasses. Projected frame lines automatically correct for parallax and a large contrasty rectangular rangefinder patch in the middle makes focusing the camera very easy. Along the bottom edge of the viewfinder is a read out for the electric eye light meter showing f/stop values from 16 to 1.9 with red arrows on each side.

With the camera in AUTO mode, the shutter will fire at whatever f/stop the needle points to. If either too much or too little light is detected for the given scene, shutter and film speed, the needle will point to one of the two red arrows, at which point the shutter release cannot be pressed. Turn the shutter speed ring around the shutter in the direction of the arrow to get the arrow off the red arrow, and the shutter release will become unlocked. If no changes to the shutter speed can get the needle away from one of the red arrows, then you’ll either need to move into different light, or perhaps consider using a flash.

In 1961 when the Canonet was first released, “electric eye” auto exposure cameras were still very new. Only a couple years prior, the only AE cameras available were very simple, usually offering a single shutter speed, fixed focus, and very little manual control. Canon would never release an interchangeable lens rangefinder with AE and AE SLRs were still a ways off, so upon it’s release, the Canonet would have been Canon’s most advanced camera.

Despite losing the interchangeable lens mount, this is not a discount camera. The build quality is excellent, with nary a sign of cost cutting, an excellent viewfinder, an excellent lens, and excellent ergonomics. As we have the benefit of hindsight to know, the era of fully functional AE rangefinders would be short lived, however that this model exists with such good build quality and the option for full manual control makes it as excellent as a choice for photographers today, as it did 61 years ago!

My Results

The Canonet would get it’s first call to action during a winter trip to northern Michigan around Christmas of 2021. For the occasion, I loaded in a bulk roll of Kodak TMax 100, which I’ve found to be the perfect film for those cold winter Michigan days with largely overcast skies. I had intended to shoot a roll of color film later that spring, but a shortage of color film and an influx of many other cameras that I needed to shoot prevented me from putting a second roll of film through the camera.

The entire time I had this camera, up until I started working on this review, I had assumed the f/1.9 Canon SE lens would have been some type of 6-element design, much like most f/2 and under lenses, but upon looking through the Canonet’s user manual, I was surprised to see that this was a 5-element Gauss design. Canon was no stranger to 5-element lenses, as they used them in everything from the motor drive half frame Canon Dial 35-2 to the “Pocket Instamatic” Canon 110ED to the Canon A35 F.

Regardless of number of elements, the Canon SE lens is a winner. Images were sharp corner to corner. The high resolution of the TMax film and it’s “T-Grain technology” combined with the stark contrast of the winter scenes I shot it in, produced extremely detailed images without any signs of optical anomalies often associated with lesser lenses.

The mirror selfie was shot with the lens wide open in full manual mode, relying on the exposure recommendations of the DOOMO Meter S I had clipped to the top. Throughout the rest of the roll, I relied on the Canonet’s internal meter, keeping it in AUTO the entire time, with the DOOMO only there to confirm exposure. It is rare when writing reviews on this site for me to rely on a camera’s built in meter for an entire roll, but with the confidence of readings that agreed with an external meter, I felt comfortable doing it. This is one of the very few selenium cell AE cameras I’ve ever relied on the meter with, and was impressed with it’s accuracy.

Beyond the meter and the lens, the Canonet performed remarkably well. Two things I regularly talk about with old cameras that often ruin otherwise excellent images are poor ergonomics and viewfinder. Strange ergonomics with difficult controls and a tiny viewfinder can be deal breakers for me, but none of that applies here. The Canonet is a well executed camera that upon it’s release would have opened the eyes to fully functional quality cameras with automatic exposure. Although we know today that bottom trigger wind cameras would quickly fall out of favor, Canon had the best implementation of it.

The best part about the Canonet is how well everything works together. With the camera to your eye and your left hand on the film advance, you can advance film, focus the lens and change shutter speeds all without relocating your hands. When shooting many images in similar lighting, set the shutter speed to a medium speed like 1/125 and the meter should be able to compensate for subtle variations in lighting without you ever having to change speeds.

There is very little to dislike about the camera. Maybe it’s a bit chunky, weighing as much as some SLRs, and I guess for left eye shooters such as my self, the location of the eyepiece in the extreme upper left corner of the back squishes your nose smack dab in the center of the back, but any complaints I could possibly come up with are well into the category of nitpicks.

This is an excellent camera from the peak of Canon’s innovation and quality era. I often hear people new to film asking for recommendations for rangefinder cameras, and although some Canonets from later in the series like the Canonet G-III QL17 are highly recommended, those models reliance on their electronics make them less reliable than these older mechanical models. Plus, with the larger and heavier all metal body, you get a sense of quality that the more compact plastic cameras lack. The original Canonet definitely belongs in the company of the most recommended cameras of the second half of the 20th century, and the best part of all, is that they still fetch pretty low prices on the used market, so whether you are new to film, or just want another quality camera with great ergonomics and an excellent lens, go buy one for yourself today!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Canon_Canonet

https://global.canon/en/c-museum/product/film41.html

https://mattsclassiccameras.com/rangefinders-compacts/canon-canonet-ql19/

https://austerityphoto.co.uk/canon-canonet-review-the-birth-of-the-prosumer-camera/

An excellent review of the Bell & Howell/Canon Canonet 19 Mike. I’ve done a little research into the original Canonet and have found over the production run there were minor improvements/upgrades to the Canonet. On version 1 the ASA range only went to 200, on version II the ASA range stayed the same but Canon added sunny & cloudy settings to make setting the shutter speed simpler but the ASA range still only went to 200. Version 3 had the ASA range extended to 400. Over the years some other minor improvements were also made. The known serial number range is 100001 to 1599999 with an estimated total of 1.5 million Canonets & Bell & Howell/Canonet 19 models produced. To date all Bell & Howell versions fall between s/n 600xxx to 1333xxx and are all I believe based on the ver. 3, but are mixed with Canon versions,the number of Bell & Howell examples produced is unknown but my personal estimate is 15-20%(225,000 – 300,000) of the total production. A couple of variations produced over the years for collectors are those engraved sold in US Military Post Exchange Stores, can be engraved in either RED or BLACK. Some late production Canonet’s have a date code in the film chamber, the earliest example I’ve identified with a date code is 1438322 with an E10 code(October 1964).

I hope these observations are of some interest.

Regards Richard

Wow! This is great info! I wish I would have known you had so much information before publishing the review, I could have included some of your info. It is cool to know that the Bell & Howell branded ones represent only about a fifth of the total production! I just checked mine and I don’t see a date code in the film compartment though, but I think you’re right, it’s probably a later production example.

The bit about Bell&Howell being a distribution partner for Canon got my curiosity concerning distributors. Topcon had a distributor. Pentax had a distributor. Mamiya had a distributor. Miranda had one. However, Minolta and Nikon did not from what I see. Now you got me looking around for why that was if there is even any info out there about why.

From the 1950s until 1981, Ehrenreich Photo-Optical Industries, Inc. (EPOI) was the official USA distributor for Nikon products.

http://183.181.162.36/about/info/history/chronology/index.htm

As Kodachromeguy mentioned, Nikon was primarily distributed by Joseph Ehrenreich who did more than just get Nikon cameras here, he was actually responsible for steering Nippon Kogaku away from rangefinders towards the Nikon F and building up their reputation here. Nippon Kogaku succeeded on the east and west coasts, but struggled in the Midwest, often relying on distribution through much smaller channels. As for Minolta, it is less clear who they used, but from what I can tell, it seems Chiyoda Kogaku opened their own US based Minolta distributor in New York, handling their own distribution themselves. I’ve seen a few other period ads mentioning someone called the FR Corporation, but I can’t find any info about them. Whatever the case, Minolta did not partner with other established firms like Bell & Howell or Honeywell like some other Japanese camera makers did.

Your review made me buy it! I’m liking it! My only pet peeve is the shutter button has quite a long and sluggish action , makes it a bit tricky to keep the camera steady when taking a shot. I’m wondering maybe if I could get some lubricant in there to make it a bit easier to take the shot