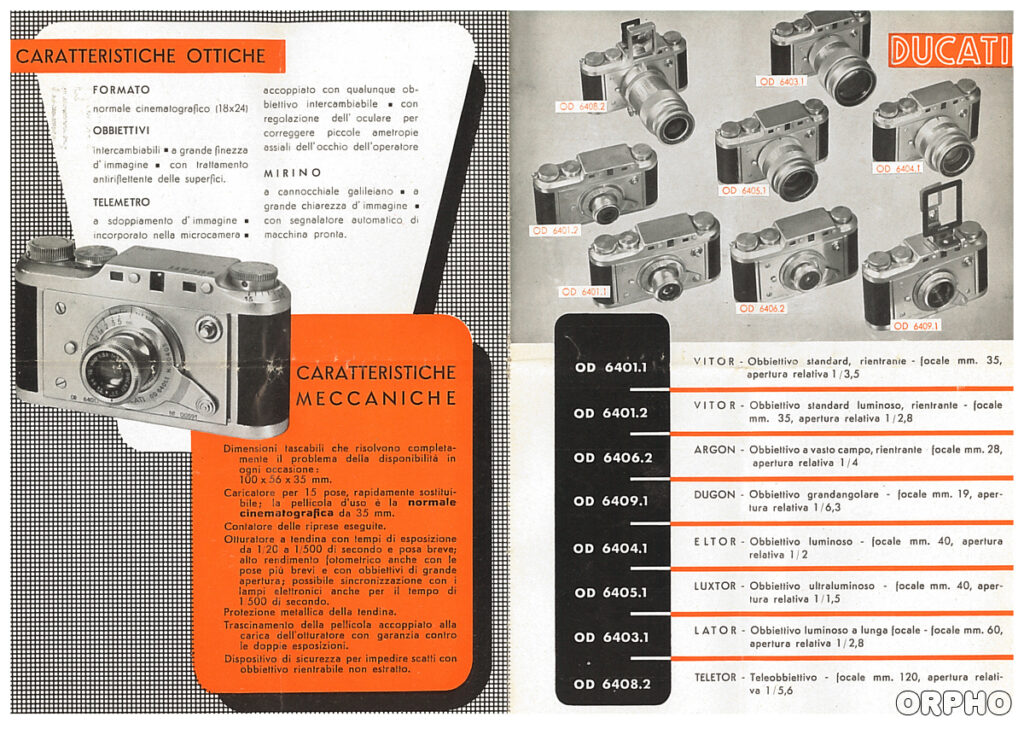

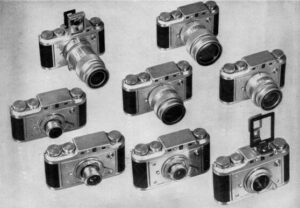

This is a Ducati Sogno, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by S.S.R. Ducati in Milan, Italy between the years 1947 and 1952. The word “Sogno” translates to “dream” and was a very tiny interchangeable lens rangefinder camera which shoots 18mm x 24mm “half frame” images on regular 35mm film loaded in special Ducati cassettes. Although the Ducati Sogno matches the German Leica in features and quality, the two cameras are very different, most notably that the Ducati is significantly smaller. Most Sognos have a model number OR 6401.1 imprinted on the body, but a very small number with PC Flash Sync were imprinted as OR 6401.11. A similar model was sold as the Ducati Simplex and shares a similar body, film cassettes, and shutter, but lacks the rangefinder.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), (15 exposures in special Ducati cassettes), Half Frame

Lens: 35mm f/2.8 Ducati Vitor coated 3-elements

Lens Mount: Ducati Bayonet

Focus: 0.8 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Viewfinder and Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/20 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 366 grams, 302 grams (body only)

Manual (pages missing): https://mikeeckman.com/media/DucatiSognoManual-1.pdf

Manual (alternate version): https://mikeeckman.com/media/DucatiSognoManual-2.pdf

If you were to mention the name Ducati to a large number of people, I suspect every one of them would recognize the name of a high regarded Italian motorcycle company. Ducati’s high performance motorcycles are known for their large-capacity four-stroke, 90° V-twin engines and exotic designs. The company regularly competes in the MotoGP World Championship having won it in 2007, 2022, and 2023. The company’s other accolades include 16 Superbike World Championships, six FIM Superstock 1000 Cups, twelve British Superbike Championships, and many others.

If you were to mention the name Ducati to a large number of people, I suspect every one of them would recognize the name of a high regarded Italian motorcycle company. Ducati’s high performance motorcycles are known for their large-capacity four-stroke, 90° V-twin engines and exotic designs. The company regularly competes in the MotoGP World Championship having won it in 2007, 2022, and 2023. The company’s other accolades include 16 Superbike World Championships, six FIM Superstock 1000 Cups, twelve British Superbike Championships, and many others.

Since this is not a motorcycle review website, clearly the company has produced things other than motorcycles. In fact, when the company was founded in 1926 by a man named Antonio Cavalieri Ducati and his three sons, Adriano, Marcello, and Bruno, the company primarily produced electronic components for radios such a capacitors and vacuum tubes.

In 1944, the company’s factories in Bologna were destroyed by Allied bombing raids, but when the company rebuilt after the war, they expanded their product offerings to include mechanical motors, bicycles, and cameras. While I could find no explanation for what their interest was in cameras, a logical explanation would be similar to other factories in European countries which was that with a lack of product coming from Germany, there was a great demand for photographic equipment and with the opportunity to produce something that could bring in money, it probably made sense to produce a camera that would be highly desired by Italian photographers.

Contrary to a lot of information online, including Ducati’s own corporate website, the company did not start making cameras in 1938. It is plausible that perhaps the idea of making a camera might have been floated around that time or a very early preliminary work, but all evidence agrees with Ducati researchers stating that the camera was first debuted at the 1946 Milan Fair and went into production in 1947. Even without that evidence, 1947 is simply more believable as that is inline with a huge number of other Italian cameras being produced at that time. Had the Sogno been created in 1938, it would have predated most other Italian cameras by nearly a decade.

According to the history section as masterpiececamera.com, the Ducati Sogno (translates to ‘dream’ in English) was announced in Ducati’s company newsletter in April 1947 and went into production in November of that same year. The camera was a very compact coupled rangefinder that shot 18mm x 24mm exposures on 35mm film loaded into special cassettes.

Ducati had ambitious plans for the Sogno, claiming to produce 1000 cameras per month and sell it for 35,000 Lire, but in reality, nowhere near that number were ever built and when the camera actually did show up in camera stores, it sold for significantly more, at 85,000 Lire. This price put it out of reach from all but the most wealthy photographers. I could not find any way to translate late 1940s Italian currency to current day US Dollars, but if I had to guess, the price likely was higher than that of even a Leica which in 1948, a Leica IIIc with f/3.5 Elmar sold at Peerless Camera for $332.50. When adjusted for inflation, this compares to $4300 today!

Even if my estimates of what the camera’s price might have translated to is off, it is still clear that the cost was very high, and that impacted sales. Still, people did buy them, just nowhere near what the company probably hoped for.

Early versions of the Ducati Sogno came equipped with a standard 35mm f/3.5 Ducati Vitor triplet, but around 1949, versions with a faster f/2.8 Vitor with coated glass was offered. The Sogno saw several minor cosmetic changes along its production including the inclusion of a post for a wrist strap, the addition of a rangefinder diopter, and cosmetic changes to the film pressure plate, the eyepiece crown, and ring snap button. A variety of lenses were planned with focal ranges from a 19mm Dugon to a 120mm Teletor. A complete list of all lenses, both released and planned is available here.

Near the end of camera production, several changes were planned to the Sogno including a model called the 6401.11 whcih would have had built in PC flash synchronization, and a model called the 6402.1 which added slow shutter speeds down to 1 second. An unseen variant called the Ducati Sport was also claimed to have been made which had a unique shutter capable of speeds only from 1/100 to 1/3000. Exactly how the camera would achieve such fast speeds at this time is unknown.

Sadly, with the promise of new and updated Ducati models, the company would cease camera production in 1952, likely due to high prices and poor sales, but also that it was increasingly difficult to source film preloaded in the Ducati’s special cassettes and that owners of the camera were not keen to manually reload them. By then, Ducati was already producing their first motorcycle called the Cucciolo, which proved to be a better market for them.

I had seen Ducati Sognos online before and was intrigued of a camera made by an Italian motorcycle company, but I didn’t get a chance to see one in person until I visited the Voncabbage collection back in 2021. The Ducati was a camera I had actually photographed and planned on writing a short article about, but I never got around to it. My second chance to handle one was in 2023 when I picked one up from an estate in California. Now with the possibility to run a roll of film through one, I was glad I waited! There was only one problem…

The Ducati I picked up was missing its proprietary cassette. Unlike other cameras that use 35mm, if either a supply cassette or take up spool is missing, where you can often reuse the core of a regular 35mm cassette, the Ducati is far too small to repurpose any inventory I already had. If I was ever going to shoot this camera, I’d need to find a real Ducati cassette. I asked around any collectors I knew with one to see if they had an extra cassette or if I could borrow one from theirs and I was surprised that every person I reached out to responded that theirs was missing the cassette too! Sadly, this means I would have to resort to buying one on eBay.

I’ll cut to the chase and say it took over six months of having some saved searches in my wishlist before one showed up from a seller in Italy for anything remotely close to a reasonable price. It took two weeks and $52 for the very tiny package to arrive from DHL, but after it arrived, I finally had a complete camera that could shoot. I don’t know how many people have ever spent that much on a single cassette, but even after factoring that cost into what I have in the entire camera, I came out ok.

Even though I had handled a Ducati Sogno before, each time I pick this camera up, I am taken aback at how tiny it is. In the image below, I show one next to a Rollei 35, and a Leica III. Many sites online suggest the Ducati is a Leica copy or like a half frame Leica, and apart from using 35mm film and having a lens and a rangefinder, the two cameras share nearly nothing in common. The Ducati is no more a Leica copy than an Argus C3 is.

One area that the two cameras do compare is in build quality. The feel of the camera is very good. Combined with its small size, the all metal body feels very dense and does not creak or twist in your hands. The chrome finish on this example is very deep and shows no signs of oxidation or peeling. The body covering is entirely in tact and still provides a good grip in your hands. This is especially useful considering the tiny size of the camera. With a slippery body, the Ducati would be a huge drop risk and that wouldn’t be good.

The camera’s controls aren’t at all Leica like, almost all of which are in different locations, but none I’d describe as difficult to use. The most drastic change is the location of the front shutter release on the left side of the camera. Two knobs on the top of the camera are for film advance and rewind. The advance knob on the left has the exposure counter built in. Ducati cassettes are only designed to hold 15 exposures each, so the counter doesn’t go any higher than that. If you use a thin base film, you can fit a bit more than 15 exposures worth of the film in there, but its not worth it to jam too much in there and risk getting it stuck.

Shutter speeds are changed by lifting up and rotating a shutter speed dial through a range of speeds from 1/20 to 1/500. The Ducati doesn’t have slow speeds, although had this camera continued production, the company was working on a model with speeds going down to 1 second. The film advance knob rotates counterclockwise and automatically stops when you’ve reached the next exposure.

Around back, there isn’t much to see other than he two viewfinder windows which have about a half inch gap between them, which isn’t far, but considering the small size of the camera, seem like they could be closer together. Notice the Ducati name embossed into the body covering.

A neat feature of the viewfinder window is that there is a red mask that partially obstructs the eyepiece when the shutter is not cocked. This is a reminder to do that before attempting to make a photo. For such a tiny camera, this is an unexpected camera and something perhaps the Leica could have benefitted from. The rangefinder is of the split image type rather than coincident image, which I actually prefer because that means there is no beamsplitter to darken the image. One hundred percent of light that enters both rangefinder windows makes it to your eye, which makes getting focus right in low light, very easy to do. In the composite image to the left, I show the viewfinder with the red mask in place indicating the shutter is not ready. Notice the increased magnification of the rangefinder, which makes achieving accurate focus, much easier.

Loading film into the Ducati is straightforward, but not as elegant as I would have hoped. For starters, the film door lock is a chintzy little lever on the bottom of the camera, that once you get it open, doesn’t look like it offers much light protection from your film. While I didn’t have any problems with light leaks on my test roll, I just don’t get the best feeling about how secure the latch is. I would be willing to bet at least some users of this camera have had issues with the back accidentally coming open.

Once the compartment is open, loading in a new cassette is pretty straight forward. Film transports from right to left using the special reloadable Ducati cassettes. Reloading the cassette is like other metal cassettes, lift the top off, slide out an inner spool, attach a strip of film using the clip on the spool and slide it back in. Pay attention to slide the spool back into the cassette in the same direction it came out because you can do it backwards. The metal take up spool is not removable, so stretch the leader across the film gate and attach it to a metal clip on the spool and give it a couple turns to make sure it is attached. Even though the Ducati uses regular 35mm film, there are no sprockets or anything to line up. With film properly loaded, slide the door back on, making sure that the front lip of the back slides into the channels on opposite sides of the lens board up front. I found this frustrating to do, as each time I tried to slide the door back on, it would never slide on correctly the first time. Perhaps with repeated use, I’d get better at this, but I found the process of attaching the back to be slow.

Up front, a button near the 9 o’clock position around the lens is the bayonet lens mount release. Press this in while rotating the lens counterclockwise removes the lens. Reattaching is the opposite, but gives a satisfying click when it locks into place. Two similar looking posts to the right of each of the two rangefinder widows are posts for auxiliary viewfinders which you would attach to the camera when using lenses of differing focal lengths. Above the camera’s model number “OR 6401.1” is a flash sync post which may or may not be original on this camera. Everything I’ve learned about these cameras is that only the very latest cameras should have a flash sync port here and this one looks different than others I’ve seen so I am not sure.

The shutter release button is externally threaded for some kind of cable release, but is too small for the types used on Leica cameras. I assume that these types of cable releases are specific to the Ducati cameras. The shutter release has a safety override feature in which you cannot accidentally fire the shutter if the lens is not retracted. Make sure you extend the lens all the way before attempting to press the shutter release.

I didn’t need to spend more than a minute or two familiarizing myself with the Ducati Sogno’s controls before I felt ready to shoot it. The camera is well designed and despite a very small size, did not cramp my hands while handling it. For my first roll, I cut a short strip of Kodak TMax 100 and loaded the $52 spool I ha bought on eBay and took it out shooting.

The Ducato Sogno may be mini, but this was a premium camera that had Leica in the eyes of its designer, so I went into this camera with high expectations, hoping for images at least as good as what I might get out of a collapsible 5cm f/3.5 Elmar, and I’d have to say, the little Ducati Vitor triplet delivered. Taking into account the half size images, I found there to be a lot of detail in the images I scanned. Contrast was a tad low, but that likely had more to do with the mid-winter scenes in which I shot the camera. Sharpness was great corner to corner without any vignetting and noticeable softness in the corners. Although a half frame camera, I wonder if the Vitor could cover a full frame camera.

I never ended up shooting color, but considering the deep blue coating on the front element, I suspect images would have come out with accurate colors and good clarity. A premium lens this was!

Any time you shrink something down, you risk compromising usability, and I was happy to see that the Ducati mostly avoided any ergonomic snafus. The location of the shutter release on the front of the camera was a wise move as putting it on the small top plate would have required a strange contortion of my index finger. That its location is on the left side of the camera was hardly an issue as I am equally adept at pushing a button with my left index finger compared to a right. In fact, in the time after shooting this camera and writing this review, I had forgotten that this was a left handed camera. The long focusing arm on the lens made quick focusing a snap, although with the lens set to anything less than 5 meters and the focus arm extends below the bottom plate of the camera meaning that you cannot put it on a flat surface like this. The arm points straight down at the 1.2 meter setting.

The viewfinder was tiny. but I did like the little red warning flag in the viewfinder which indicates that the shutter is not set. For how small of a camera this was, I was surprised at how far apart the viewfinder and rangefinder windows were. I would have preferred if they were closer together like on the Leica IIIb and above.

Beyond these minor nitpicks, I found nothing to dislike about the camera. In fact, unlike other tiny cameras like the Concava Tessina, Goerz Minicord, and Bolta Photavit which put compactness over usability, I found that shooting the Ducati Sogno was surprisingly “full size like”.

If there’s one drawback to this camera, it is its exclusive price. This is a highly desirable and rare camera. Considering the difficulty I had in finding a cassette, I suspect that many of those that do exist in private collections are not in a usable state. For as great of a camera this is, it is not something I can easily recommend to someone wanting to shoot a half frame camera. The price is prohibitive with current eBay auctions all greatly exceeding $1000, this is simply not a camera many people will get a chance to shoot. If, by some grace of luck you do get a chance though, spend the $52 on a cassette like I did as it is worth it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Sogno

http://www.masterpiececamera.com/ducati-sogno-history.html

https://bencinistory.altervista.org/002A%20fotocamere%2046-64/01F%20DUCATI%20sogno.html (in Italian)

http://www.submin.com/35mm/collection/ducati/introduction.htm#P1

https://www.cameraquest.com/ducati.htm