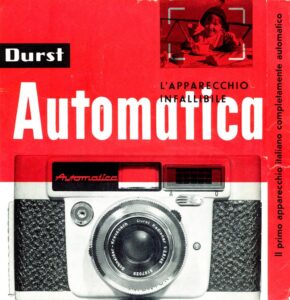

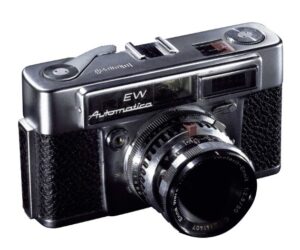

This is a Durst Automatica, a 35mm viewfinder camera made by Durst Phototechnik SA in Bolzano, Italy between the years 1956 to 1963. The Durst Automatica was an elegantly designed camera that is notable as having one of the earliest implementations of automatic exposure in a 35mm camera, beating a huge rush of AE equipped cameras by at least 2 years. The auto exposure system was very similar to the one used by AGFA in their AE equipped Automatic 66 from the same year. Powered partially by the camera’s selenium light meter and a pneumatic Prontor-SVS shutter, the Durst Automatica was able to automatically set it’s shutter speed in a variety of lighting conditions.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Schneider-Kreuznach Durst Radionar coated 3-elements in 2-groups

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity (unmarked down to 3 feet)

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Prontor-SVS Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell w/ top plate exposure display and Aperture Priority AE

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 676 grams

Manual (in Italian): https://mikeeckman.com/media/DurstAutomaticaManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Durst Automatica is a cleverly designed and innovative camera that is historically significant for being the first mass produced 35mm camera with automatic exposure. It comes in a high quality and elegant body with a good German lens and shutter, a large and bright viewfinder, film advance lever, and a wide range of shutter speeds. Made by a company better known for making darkroom equipment, the Durst Automatica is the finest camera made by it’s company, and one of the coolest Italian cameras ever. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.7 | ||||||

History

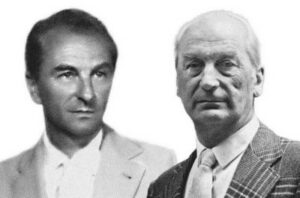

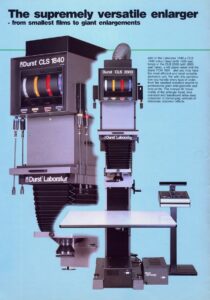

The name Durst isn’t one that many western photographers today likely have heard much about. This Italian company was founded in 1936 by brothers Gilbert and Julius Durst, and for a large part of the mid 20th century was one of the largest producers of photographic enlargers and slide projectors.

The name Durst isn’t one that many western photographers today likely have heard much about. This Italian company was founded in 1936 by brothers Gilbert and Julius Durst, and for a large part of the mid 20th century was one of the largest producers of photographic enlargers and slide projectors.

Both Gilbert and Julius Durst had an interest in photography from a young age. Their mother was a photography enthusiast who had a darkroom in their house and their father was a painter, who also enjoyed photography. In addition to having an interest in photography, the Durst brothers both had an interest in building things, building radios, hunting and sailing equipment, and even a bob sled in their free time. As they got older, Julius attended a technical academy in Konstanz and Gilbert went to work for a photo dealer.

By 1929, the Durst brothers took on side jobs building and repairing equipment for local photographers. With Julius’s knowledge of engineering and design and Gilbert’s knack for sales, the two brothers built and sold a large number of accessories, but perhaps their most successful product is one that would foreshadow their later business, a custom enlarger for magic lanterns. A magic lantern is a simple device that can take a photographic plate and using a light source and a lens, project it on a flat surface. With the Durst enlarger, the images could be shown in a much larger size without losing brightness.

For the next couple of years, the Durst brothers stayed busy with their hobby, but still had to work a full time job to support themselves. In 1933, unhappy with the amount of time they were spending at their day jobs, they decided to go all in and open their own business. Without much capital, the brothers sought financiers from local businesses, and eventually caught the attention of a local leather goods company called Alois Oberrauch & Sohne with whom they partnered. In their new agreement, the Dursts would be responsible for the technical aspects of photography and the Oberrauchs would handle the finances. Over the next three years, the foundation for a new company was laid and in 1936, Durst Phototechnik AG was born.

One of the company’s most successful products of the time was a roller photo copier that could reproduce copies of post cards. The area that Durst was located had a huge tourism industry, so making copies of post cards as souvenirs proved to be popular. Although the copiers were successful, it wasn’t enough to support the fledgling new company. To maximize profits, a series of enlargers, negative holders and in 1938, cameras began production.

The first Durst camera was called the Gil, and it was a simple, but well constructed box camera. The Gil, most likely named after Gilbert Durst, shot 6×9 images on 120 roll film. It had a single speed shutter, but an adjustable exposure control allowing some flexibility in different light. The Gil became an instant success, requiring a new factory to be set up exclusively for camera production. The camera was exported out of Italy, as versions of the Gil have been found with markings in German, Swedish, and English in addition to Italian. The camera was produced until 1942 or 1943 when the factory switched over to war time production.

Also during this time, a large number of photographic enlargers were created, including some with an early version of automatic focus, and some which could produce images as large as 30 cm x 40 cm.

After the war, Durst got back to work making enlargers and resuming production of the Gil. To further it’s camera sales, a new camera called the Duca was released. The Duca was very small and had an oval shaped body reminiscent of an 8mm cine camera. The Duca was not a motion picture camera however, as it shot 12 exposures on regular 35mm film loaded in AGFA Karat cassettes. The camera came in a variety of colors with finishes in black, brown, blue, red or white.

In 1949, a third model, simply called the Durst 66 was a large solid bodied camera that shot 6cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. Although having a somewhat normal shaped body, the camera had a hammertone metal finish with an elaborately decorated top plate and a couple of unusual features.

The shutter was unique as it used pneumatics to control each of it’s 8 speeds from 1/200 second down to 1 full second. How it worked was that by winding on the film, the shutter was also cocked. In cocking the shutter a small amount of air was compressed into a cylinder. Then depending on the chosen shutter speed, a series of openings of different sizes would cover a release value of the cylinder. When pressing the shutter release, the shutter would open, and the air would be released from the cylinder through whichever hole was chosen and then the shutter would close. The larger the hole, the faster the air was released and the shutter closed. A smaller hole meant it took longer for the air to escape and therefore, the shutter remained open longer.

Another unusual feature was the metering system which was essentially an extinction meter on the top plate with four icons to indicate different lighting conditions. As light would enter through a window on the front of the camera, it would be reflected up through the four windows. Depending how much light light there was, you could see 1, 2, 3, or all 4 windows. Depending on which windows were visible, depended on what the exposure should be.

The Durst 66 was produced for about five years, ending production in 1954. Although a modestly spec’d camera, it’s unorthodox shutter and method for measuring exposure hinted that the Durst brothers wanted to find new solutions to existing problems, and create something unlike anything else out there.

The company’s next, and last camera, was their most ambitious to date. In 1956, Durst would release the Automatica, an innovative camera that used a similar pneumatic shutter like the one from the Durst 66, but the camera’s biggest feature was a very early implementation of Aperture Priority Automatic Exposure.

In a strange twist, according to a story on Durst’s Company History page, it says that the AE system on the Automatica was based off instruments found on a crashed American bomber that was found in Brixen, Italy, near where Durst was located. If this is true, then it suggests Durst had been investigating the possibility of auto exposure quite a bit before the camera was released.

Another story that is more commonly referenced is that once Durst’s auto exposure system was completed, it was shared with, or perhaps sold to AGFA for use in the AGFA Automatic 66, a medium format roll film camera capable of auto exposure released in 1956.

1956 or 1960: There is conflicting information about the year of the Automatica’s introduction, some saying as early as 1956, some saying 1960. In the book, “MADE IN ITALY, apparecchi fotografici italiant by Marco Antonetto and Mario Malavolti, the year is credited as 1956, and in a very well researched and thorough website on the history of Durst, it is stated as 1960, but I believe 1956 is more accurate.

My reasoning is that if Durst allowed AGFA to use the same metering system in a camera they released in 1956, it makes no sense for Durst to wait four full years before releasing a camera of their own. Plus, the metering system in the Automatica is pretty basic, which would have made sense for 1956. But over the next four years, a huge number of auto exposure “electric eye” cameras would make their debut, and by 1960, the system in the Durst would have been sorely outdated.

Whether or not the story of Durst’s inspiration for an auto exposure system form a crashed WWII bomber is true, it’s a fun story to contemplate. Whatever the case, Julius Durst would file a German Patent DED0011595A in February 1952, and a US Patent US2800844A in January 1953 for what he called “Automatic Control for Photographic Cameras”. This patent detailed how his auto exposure system would work. With the Super Kodak Six-20 as the only commercially produced auto exposure camera, Durst had little to work with, so it likely took another 3-4 years before such a system could be released in a camera.

The Durst Automatica would turn out to be the company’s last camera, but also their most advanced. Featuring an elegantly designed body with a German Prontor-SVS leaf shutter and 45mm f/2.8 Schneider-Kreuznach Durst Radionar lens, it was a considerably higher end camera than anything the company had produced before. Although I have no evidence of this, perhaps the leap the company was able to make from simple cameras with f/8 and slower achromat lenses to something like the Automatica, could possibly have been part of the arrangement with AGFA to use their auto exposure system. It stands to reason that Durst might have allowed AGFA to use their system in exchange perhaps for access to Schneider lenses and Prontor shutters.

However it happened, the Durst Automatica would be the third commercially marketed camera with Auto Exposure behind the AGFA and the Super Kodak Six-20 and the first ever 35mm camera with the feature. At least two variants of the camera were produced, both nearly identical with the only external differences being the location of the serial number. Earlier versions of the camera have the serial number engraved inside the film compartment under the film gate, and later ones have it engraved on the front of the camera, below and to the left of the shutter.

Note: An otherwise excellent Italian language resource for the Durst Automatica states that earlier cameras with the serial number in the film compartment all begin with the number ‘6’ and all with the number on the front of the camera begin with ‘7’. This is not true as the example I have is number 70767 and the number is still in the film compartment. Perhaps at whatever time the location of the number changed, it was closer to 71xxx.

The following article appeared in the Italian language magazine, Notariziaro Erca in December 1960, explaining the inner workings of the Automatica. If you do not read Italian, there are a couple good images of the metering system. You can also try Google Translate to get an idea of what is being said.

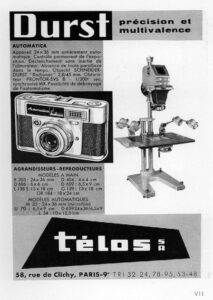

I could not find any information about which countries the Durst Automatica was exported to, but with Durst’s history exporting their earlier models like the Gil to countries like England, Germany, and Sweden, it is plausible that the Automatica was sold there as well. In my research for this article, I found no evidence that the camera was sold in the US. I cannot speculate what the camera might have cost back then as the few European ads I could find for the camera never mention a price, but it’s probably safe to say ‘more than cheap, but less than expensive’.

A variation of the Durst Automatica with the letters “EW” in the model name was developed at some point during the Automatica’s life, possibly as a replacement or supplementary model. The first of two changes to the EW model is an opening above the word “Automatica” that clearly looks like a rangefinder window, suggesting a rangefinder was planned for the camera.

The other obvious change is that the lens is a 50mm f/2.8 Enna Werk München Photavia-Ennit, possibly suggesting the camera had an interchangeable lens mount. An identical lens was produced by Enna Werk München for the interchangeable lens Photavit 36 camera which was produced between 1956 and 1958. That the lens specifically says “Photavit” suggests that the lens on this particular example was not created for it, and possibly used as a placeholder. It is even possible that this EW is a mock-up done by some ambitious fan of the camera, but I find the presence of a rangefinder window to be pretty conclusive that this was it’s own separate model. Whatever the story is about the EW Automatica, it never went into production and the only images found online appear to be the same camera.

The length of time the Durst Automatica was produced and how many were made isn’t well known. Some sources online suggest that as many as 50,000 were made, but based on serial number analysis of known examples, the actual total is probably somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000. As for when the camera ended production, it definitely was before 1964, as that was the year that both Durst stopped making cameras altogether, and also when Julius Durst would tragically die in an automobile accident.

Julius Durst’s death may or may not have been a factor in why the company stopped making cameras, but another reason I think that date is right is that it coincided with a general end of most non-German camera production in Europe. In the years after the war, widespread sanctions on Germany prohibited or made very expensive, the sale of German goods to other European countries. As a result, photographers in countries like Italy and France couldn’t get German cameras, and the Japanese market wasn’t big enough to support distribution there, so a large number of new and existing companies made cameras to meet the demand. Companies like Ferrania, Durst, Royer, and OPL churned out dozens of models, ranging from simple box cameras to SLRs.

By the early 1960s, trade with Germany resumed and German cameras started to become easier to get. In addition, more and more distributors were making Japanese models available, which put pressure on domestic camera makers. Realizing that there was too little profit to be made, and that imported cameras were superior, between 1963 and 1965 companies like Royer and Ferrania ceased making cameras (OPL kept making Foca cameras until at least 1967, but they were significantly cheaper models) and while I don’t have any proof this is what happened to Durst, it definitely fits.

After the company exited the camera making business, Durst continued on with their primary goal of producing enlargers and other darkroom equipment. For the next couple of decades, Durst would remain a leader in this market, continuing to produce new models until the end of the century. By the early 21th century, things slowed down for Durst, and in 2005, would end photographic production to concentrate on professional large format laser and inkjet printers.

Today, there are a small but loyal group of Italian camera collectors. Models like the Rectaflex SLR and Ferrania Condor rangefinder are very desirable, as are the large number of simple 35mm and other box cameras. The Italian camera industry is richer than you’d at first think, and models like the Durst Automatica are often some of the most sought after models for their innovation, good looks, and quality. Whether or not you specifically seek out Italian cameras or not, the Durst Automatica is one you shouldn’t pass up if you have an opportunity to add one to your collection.

My Thoughts

I can’t remember the first time I saw a Durst Automatica, but recall being enamored by it’s looks and it’s historical significance as being one of the fist auto exposure cameras. Italian cameras don’t come by US based collectors often, and when they do, the prices are appropriately high, so I put the camera on the back of my “one day wish list”.

It would take until the summer of 2022 when one would show up in a lot of one of those “I don’t know much about cameras” lots where nothing was described other than “vintage”. In it were the usual assortment of common Japanese SLRs, third party lenses, and probably a few Kodak Instamatics. But there in the back was an interesting camera that I didn’t at first recognize. After some creative sleuthing of capturing screenshots and enlarging them in Photoshop, I concluded it was a Durst Automatica and put up a bid.

As I had hoped, this example of a seller putting forth absolutely no effort to properly list what they had, resulted in me getting a smokin’ deal on a camera I hadn’t even so much as held in person before.

When it arrived, I was pleased that the camera was in very nice cosmetic condition. The meter was dead, the little plastic window that covers the meter needle on top was missing, and the leather was starting to peel in the corners, but otherwise I was happy, especially considering the stupid-low price I paid for it. The build quality seemed very high, at least compared to German models of the era. The chrome was bright and smooth, and showed no signs of oxidation. The Schneider-Kreuznach Durst Radionar was clean and the Prontor-SVS shutter opened and closed.

One of my favorite features of the Automatica is the flatness of the top plate. With the exception of the edges of the accessory shoe, the camera could sit upside down on a flat surface without falling over. On the left is the rewind knob which in normal use cannot be turned without popping it up. To do that, pressing the rewind release button on the bottom of the camera not only deactivates the film transport, but a linkage to the top plate causes the rewind knob to rise up so you can grip and turn it. When you are done rewinding, you must press it back down while giving it a slight clockwise twist to lock it into position.

To the right of the rewind knob is an attractive red and black meter display. A white needle under a curved opening displays shutter speeds that the camera will select in auto exposure mode. The Automatica uses Aperture Priority Auto Exposure, which means you control the f/stops and the meter controls the shutter speeds. Only with the shutter set to a red “300 automat” setting does the AE system work.

Next is the accessory shoe and next to that is the film advance lever, which like the rewind knob is recessed into the top plate. The entire wind lever is made of metal and the tip has sharp jagged edges which technically make it easier to grip, but definitely hurt your skin if you wind on the camera with too much force. While I appreciate the elegance of an all metal lever, this is one of the camera’s few poor ergonomic choices. Above the wind lever, the Durst logo is engraved into the plate.

Flip the camera over and like the top plate, the rewind release button and centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket are flush with the rest of the plate. Around the circumference of the tripod socket is a black piece of body covering which would help to hide scratches which can sometimes happen from the camera moving around while on a tripod. As mentioned above, pressing the rewind release button not only readies the film transport to be rewound, but it also pops up the rewind knob and resets the exposure counter.

Around back, below the accessory show is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder, and to the right is the automatic resetting exposure counter. The exposure counter resets back to zero when pressing the rewind release button, but not when opening the door, like on other cameras with this feature.

The sides of the camera have little to see, other than the film compartment release on the camera’s right side. The Automatic lacks any strap lugs, which means if you want to connect it to a neck strap, you either have to have the original case, or use the kind that attach to a tripod socket.

The left hinged film door opens to reveal an elegant, but ordinary 35mm film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed and metal double slotted take up spool. The double slots on the spool are not opposite each other and are intended to be used together by sliding the film through one and folding around the other. The take up spool, sides of the film gate, and inside of the door all have a nice ribbed pattern which I don’t think does anything, but certainly looks nice. Above and below the film gate are four half circles which correspond to half circle bumps above and below the pressure plate which help keep it still while film transports through the camera. The pressure plate itself is very large, and made of black painted metal. Lastly, on this example of the Durst Automatica, the serial number is engraved below the film gate. Later versions of this camera have the serial number on the front face, below and to the left of the lens.

Looking down on top of the shutter are controls for focus, shutter speeds, and a combined film speed and aperture ring. Starting with focus, the entire front lens grouping rotates smoothly from an indicated minimum focus distance of 3.5 feet to infinity, with a single click stop indicated in red at 10 feet which is to be used for group shots. The focus ring goes quite a bit below the 3.5 foot indicated mark, although I am unsure exactly how far.

Behind the focus ring are the shutter and aperture control rings which at first look coupled, but they are not. The shutter speed ring turns as you’d expect with click stops from 1 to 1/300 plus Bulb. The 300 speed is in red and marked with the additional word automat which is where it must be for the auto exposure feature to work correctly. Setting it to 1/300 does not actually enable auto exposure mode however, this must be done in a second step, explained below.

The aperture control ring is unique in that right next to the shutter speeds are DIN film speed settings, making it look like it’s the film speed setting. If you turn the camera and look on the right side of the shutter (left from up front), f/stops from 2.8 to 22 are indicated in red. On the opposite side of the shutter are ASA film speed settings in green. Each of the seven f/stops correspond to DIN speeds 9 through 27 and ASA speeds 6 through 400. Normally, the DIN / ASA / aperture ring is locked and cannot be turned without first press and holding a little button to the left of the DIN 9 setting.

The auto exposure system on this camera controls the shutter speeds based on a single aperture which corresponds to what film speed you have in the camera. So while the camera is technically aperture priority as you can choose whichever f/stop you want, if you follow the camera’s original instructions it is only calibrated to an f/stop that matches the speed of the film you have in the camera.

Lastly, on the side of the shutter with the red f/stops, is a separate lever for choosing between M and X flash sync, and a third green V setting which is for the delayed action self timer. The letter “V” is often used on cameras with German leaf shutters as it stands for “Vorlaufwerk” which loosely translates to “self-timer”.

Up front, the camera’s elegant lines continue with a really attractive Automatica logo on the front window, reminiscent of other prestigious Italian brands like Ducati or Ferrari. Below the logo is the shutter release with a threaded socket for cable release in the center. Originally, a very thin piece of body covering would encircle the cable socket, but on this and most examples of this camera, the leather is missing. I was unable to cut a circle the correct shape to cover the original, so I just made a circle that covers the hole too as I think it looks nicer this way and I’m not likely to ever use a cable release on this camera.

On the opposite side of the front, is the opening for the Metraphot exposure meter. Below the meter is a lever with two settings, A for “Automatic” and O for something in Italian which means “not-Automatic”. The user manual suggest the “O” setting is to be used any time you want to manually control the shutter, or for flash photography. Below this lever is a standard flash sync connector.

The viewfinder is large and bright. Projected frame lines approximate the 45mm focal length of the lens and are easy to see, even while wearing prescription eyeglasses. The Automatica does not have any type of automatic parallax correction, nor are there any marks to indicate close focus. The primary viewfinder takes on a bluish tint, which makes the frame lines easy to see. It would be easy to mistaken the Automatica as having a rangefinder, but unfortunately, none is present. There is nothing else visible in the viewfinder about the camera’s exposure settings, nor a meter read out.

There is a lot to like about the Automatica. It has a build quality above most other Italian cameras, and comes with an excellent lens, and an innovative feature set. I wish the camera was a bit more successful so that more people could have the experience of shooting one, but it wasn’t, so you’ll just have to live vicariously through me. Now that you’re doing that, you probably want to know, “well Mike, how good is it? Why don’t you tell me now?”

My Results

Before taking the Durst out for it’s first roll of film, I inspected everything and although the meter was dead, I had always intended on using it manually anyway as I rarely trust half century old selenium meters. I noticed that of the available shutter speeds, 1/125 and 1/300 worked consistently, but 1/60 would sometimes sound OK, but other times sounded off to the ear. 1/30 would only fire about half the time, sticking on the others, and anything slower didn’t work at all. As I often do, I tapped into my supply of good ole Kodak TMax 100 and took the camera out for it’s inaugural roll. I shot almost everything at 1/125, making adjustments to exposure using the diaphragm.

Although the style and design of the Durst Automatica is undeniably Italian, the camera’s lens and shutter are 100% German, so before I had even removed the lid from the Paterson tank my film was in, I had high hopes.

As I expected, upon letting the film dry and scanning it into my computer, I saw a whole roll of mostly sharp and properly exposed images. Even though the Durst lacks a rangefinder or any kind of focus aide, all but 3-4 images were properly in focus. The one problem the camera had was that as expected, the slow speeds were off. My mirror selfie pictures usually require a shutter speed of 1/30 and f/4 using TMax 100, so I tried to compensate by opening the lens wide open to f/2.8 and shooting it at 1/60 which did work, but the sluggish blades blurred the image. Every image I shot outdoors at 1/125 however, turned out great.

The Schneider-Kreuznach Durst Radionar performed as did every other Radionar I’ve shot, which is excellent! The Radionar is one of the best three element lens designs I’ve ever used, well on par with Zeiss Novar and Schneider Xenar lenses. I’ve shot cameras as far back as the Certo Dollina II from the 1930s with this lens and have always been impressed with it’s performance. Images are sharp corner to corner with hardly any indication of softness or vignetting near the edges or the corners. Perhaps one of the only weaknesses of the lens is that is gets very soft wide open as my lower light images show.

Since the meter was dead on the camera, I was unable to test the auto exposure system, but chances are, it probably would have worked well as I shot almost the entire roll in well lit outdoor scenes that even the simplest of meters should have no problem with.

The ergonomics of the camera are mostly excellent, with my only complaint being the incredibly sharp edges of the film advance lever. While I completely understand the need to put a texture on the tip to increase grip, Durst’s choice of sharp saw teeth was poorly thought out and wears down on your fingertips after only a few uses.

Aside from that, the balance and heft of the camera, location of the front shutter release and the exposure controls were a joy to use. I’ve commented on this over and over again on this site, but I love cameras with front shutter releases like this, the Teraoka Auto Terra Super and Miranda SLRs as they help further stabilize the camera while pressing it into your face.

Although this was only Dursts’s fourth camera they ever made, but it was also their last, which is a shame as they clearly had a knack for building a great camera. The presence of an EW model with a rangefinder and interchangeable lenses suggested that future development was at least considered. While changing lenses wouldn’t have made the camera significantly better, I think a rangefinder would have broadened it’s appeal, and if a Durst Automatica 2 would have followed it up a couple years later with more updates, there’s no telling how good it could have been.

Of course, none of that happened, but as the final camera from Durst, the Automatica is their best. It is a very nicely put together camera with Italian style, a great lens and shutter, and had a pioneering auto exposure system. If you ever have a chance to pick one of these up in anywhere close to good working condition, I definitely recommend it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Durst_Automatica

http://knippsen.blogspot.com/2020/05/durst-automatica_29.html (in German)

https://sites.google.com/site/harrissonphotographica/home/durst-automatica?pli=1

https://retrofilmcamera.com/durst-automatica/

http://www.cjs-classic-cameras.co.uk/other/italia.html#durst

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/228655-durst-automatica-an-appraisal/

http://bencinistory.altervista.org/002A%20fotocamere%2046-64/01E%20durst%20AUTOMATICA.html (in Italian)

http://www.topgabacho.jp/FI/Durst.htm (in Japanese)

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-10184-Durst_Automatica.html (in French)

There is one other Durst model, using Agfa’s Rapid cassettes. Several are for sale on The Bay, and all are in the Netherlands: https://www.ebay.com/itm/324845038989

Noticed your Durst Automatica does not have the serial number etched on the front left of the bottom plate like some that I see posted online. Mine, like yours, is printed (70540) inside the back under the film guides.

I have only seen 2 in Australia. One which I own, bought for A$10 at a flea market and another that I saw gathering dust in an antique camera shop at Bowral, NSW. Most likely they were brought in by immigrants from Europe.

Yes, the location of the serial between early and later ones is something I touch upon in the article. This is the most obvious difference between the two variations of the camera. Very little else seems to be different, however. Cool to hear you got yours for so cheap, what a bargain!

First of all, congratulations for the article! It clearly show you made lot of research and gathered plenty of information about Durst, and Durst cameras.

But you are wrong about some points, that I would like to correct:

GIL camera production was never resurrected after WW2. At least, not under the Durst name: it was instead marketed by another company, Ropolo of Turin, as the Ro-To Juve (actually manufactured by Riber – Turin, as Ropolo was just a distribution company.

Durst 66 entered in production in 1956, not in 1948. If you need, I can send you a scan of the May 1956 issue of the italian photographic magazines “Progresso Fotografico” announcing it as a new product from Durst.

Automatica entered in production between the end of 1960 and the beginning of 1961. Again, this can be proved by magazines of that years, announcing it as newly presented camera.

Automatica’s S/Ns analysis, compared with that of enlargers of the same era clearly suggest that no more than 10,000 Automaticas were manufactured (probably even less): at taht time, Durst used a unique sequence of S/Ns for all the products: enlargers, cameras, etc. The numbers were apparently assigned per “lots” of different consistence, depending of the product (I have discovered this pattern by analyzing more than 1800 Durst S/Ns from 1936 to 1966). All the serials before 66000 are taken by enalrgers – between 66000 and 77000 almost all the serials belongs to the Automaticas, with small lots of enlargers in the between – after 77000 all the serials are again taken by enlargers. The lowest Automatica S/N I could record (up to-day) is 66074, the higher is 76843.

Should you need any other info or detail about Durst cameras, drop me an e-mail.