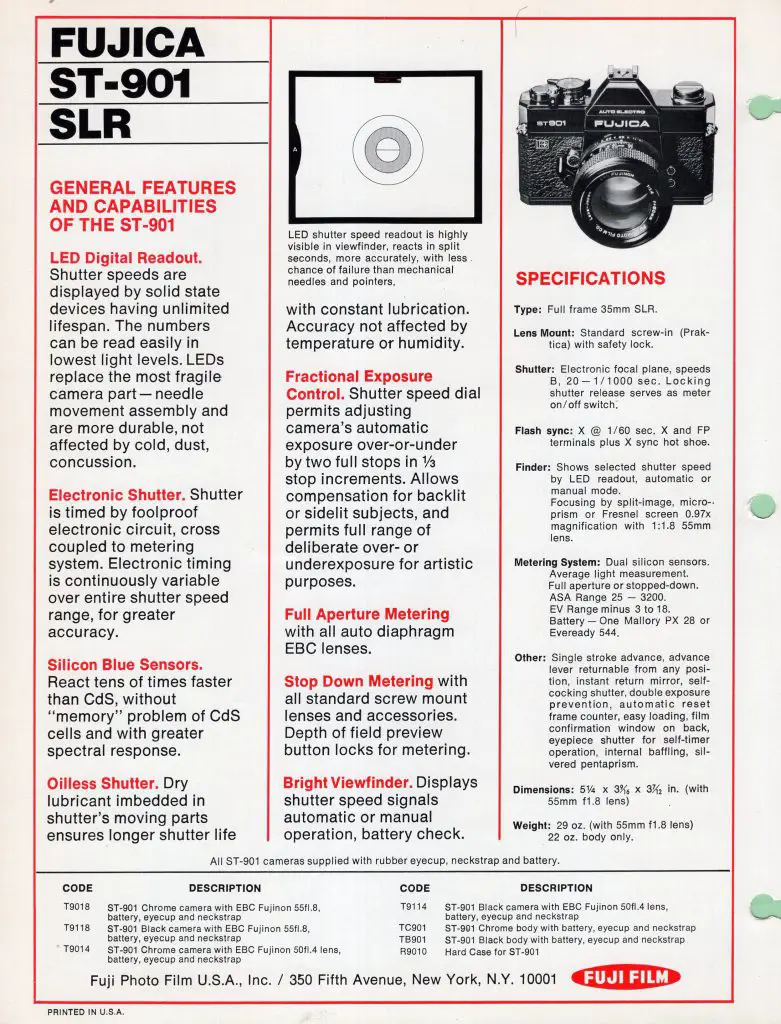

This is a Fujica ST901, a 35mm SLR produced in Japan by Fuji starting in 1974. The ST-901 had a long list of features including TTL metering, aperture priority automatic exposure via a Silicon Photo Diode, an electronic shutter with step less speeds from 20 second to 1/1000 second, digital LED viewfinder display, open aperture metering, a film cassette inspection window, and a viewfinder blind for long exposures. Although equipped with the regular M42 screw mount, Fujinon lenses for this camera have a specially designed indexing tab which is required for automatic exposure and open aperture metering to work. The ST-901 was Fuji’s top of the line camera and one of the most advanced M42 screw mount cameras ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/1.6 Fujinon coated 5-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Fujica M42 Screw Mount (indexing tab is required for automatic exposure and open aperture metering)

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with Digital LED display

Shutter: Electronic Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds (automatic): 20 – 1/1000 seconds, step less

Speeds (manual): B, 1/60 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: (2x) Coupled Silicon Photo Diode w/ Aperture Priority AE

Battery: 6v PX28/4LR44 Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and FP and X Flash Ports, 1/60 X-sync

Weight: 830 grams (w/ lens), 641 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/fuji_pdf/fujica_st901.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Fujica ST901 was one of the most advanced SLRs ever made by Fujica and one of a few screw mount SLRs capable of auto exposure. It has all of the features a modern SLR shooter would want, including a very cool red LED shutter speed display in the viewfinder. Operation of the camera is pretty run of the mill, but if you want to use the camera in auto exposure mode, you’ll need to use the correct Fujinon lens for it, otherwise with any number of excellent M42 lenses made over the years, you’re assured of getting excellent results from one. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an overabundance of quality and features in an M42 camera | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.0 | ||||||

History

The ability for a camera to automatically detect light and make an appropriate change to it’s settings in the interest in getting a properly exposed image is not a new concept. Inventors have dabbled with automatic exposure since the turn of the 20th century, but the first camera to do it successful was the Kodak Super Six-20 from 1938. With it’s “electric eye” selenium meter, the Super Six-20 could automatically change the size of the iris to accommodate the amount of light entering the meter.

Although a short lived product that sold in modest numbers, if you wanted auto exposure in 1938, it was your only option. By the middle of the 20th century, models trickled out with automatic exposure like the AGFA Automatic 66 in 1956.

In 1958, an explosion of auto exposure cameras hit the market. In less than a year, six new models were released by Kodak, Revere, Braun, Bell & Howell, and AGFA all with electric eye automatic exposure. All were very basic models, many of which only supported a single shutter speed, minimal use of manual control, and all had non-interchangeable lenses.

Since auto exposure was still a pretty new concept, implementing it in simple cameras allowed the metering systems to remain simple too. A scale focus box camera with a single speed shutter and fixed lens is a lot easier to accommodate the pieces necessary to make auto exposure work than a complex interchangeable lens SLR.

The first SLR with automatic exposure was the Royer Savoyflex Automatic from 1960, which had a very simple system and a fixed lens. It wouldn’t be until 1965 when Konica would release the Auto-Reflex, the first interchangeable lens SLR with automatic exposure. In those days, automatic exposure cameras were shutter priority only, in which the metering system could only automatically control the iris of the lens. Aperture priority auto exposure would not become common until a couple of years later due to the complexity of detecting the chosen f/stop on an interchangeable lens.

The challenge with interchangeable lenses was that since the iris is in the lens and the lens is removable, there needed to be a way for the camera’s in body metering system to not only change the size of the iris, but also understand what the range of f/stops the lens had. If a metering system assumed you had a lens with a range of f/stops from f/1.4 to f/16, and then you suddenly changed to a slower lens with a range of f/3.5 to f/22, the metering system would need to be adjusted as well.

Konica addressed this with the Auto-Reflex by coming out with a new bayonet lens mount called the AR-mount which allowed the camera’s body to always know what kind of lens was attached and control the iris. Although Konica already had an earlier bayonet SLR mount for it’s original Konica F in 1960, the mount wasn’t designed for metering in mind.

Other companies like Nippon Kogaku, Canon, and Minolta who already had bayonet lens mounts would revise their existing mounts to add internal couplings, or in the case of Nippon Kogaku and Miranda, external couplings which accomplished the same feat.

Automatic exposure quickly caught on. The first models had body mounted meters, and eventually more complex TTL (through the lens) systems were implemented, along with aperture priority auto exposure, and eventually, programmed auto exposure.

Of all the cameras available with auto exposure, there was one camera mount that couldn’t support it, and it turned out to be the most popular mount at the time, the M42 Screw Mount. The M42 mount was simply a larger version of the Leica Thread Mount, first developed in 1930 for the Leica I Model C. Although supported by nearly every lens maker, the M42 screw mount lacked any communication of it’s settings back to the camera. When you mounted an M42 lens to the camera, whatever metering system the camera might have would have no idea what the maximum aperture was, or what the iris was set to.

When auto exposure first hit the market, it was typically on more expensive cameras, and by the late 1960s, M42 cameras were generally less expensive models, so there wasn’t much demand for automatic exposure on those models.

Things would start to change in the 1970s as cameras continued to get simpler and easier to use. There was a demand for a cheap SLR with automatic exposure, and rather than direct consumers to a more expensive Nikon or Canon SLRs, companies like Asahi Pentax, Chinon, Fujica, and Yashica looked at ways to implement the feature into their screw mount models.

As you might imagine, when you task several different companies to all come up with a solution to a problem that they all face, each one will have a different opinion of how to go about it. Although the M42 mount was universal between all companies that used it, how to index a lens was not.

In the end, every single maker of an M42 mount camera who took up the challenge of adding automatic exposure, came up with a different solution, which required different lenses, none of which were compatible not only with each other, but with older M42 lenses designed for other cameras. In each instance of an M42 camera that had auto exposure, each one of them required a specific lens to make it work properly. You could still mount other lenses to these cameras, but either the camera had to be used manual only, or in some cases, could still be used, but only when manually stopped down.

For Fuji, who already had a successful family of SLRs, in 1974 would release the Fujica ST901, complete with shutter priority automatic exposure, but only when mounted with Fujinon lenses with a Fuji-specific indexing tab. Thankfully, Fuji had the foresight to add this tab to most of their lenses made at the time, whether they were used on the ST901 or not. So if a user had an earlier model like the ST-605, there was a good chance the lens they already had would be compatible with the ST901.

Of all the available M42 mount SLRs with auto exposure, the ST901 was the most innovative, not only for it’s implementation of AE, but also that it added features like an 8-segment LED display in it’s viewfinder and a film cassette peep window on the film door, both features not found in any other camera. Although a film first company, Fuji had a reputation of making high quality and innovative cameras like the Super Fujica-6, Fujica Drive, and Fujicarex II.

When it first went on sale, the camera could be had with either a Fujinon EBC 55mm f/1.4 or f/1.8 lens. The prices for each were $605 and $545 respectively, which when adjusted for inflation, compare to about $3150 and $2825 today. This was quite an investment for a camera using a mount that by all accounts, was barely hanging on well past it’s expiration date.

In their August 1974 issue, Modern Photography put the ST901 through it’s paces going into great detail about the camera’s many innovative features including the new Silicon Blue Cell metering system, LED display, and film window.

The article discusses the new technology in the ST901, commenting how digital displays on calculators and watches has foretold similar technology in cameras. It praises how quiet the shutter is, comparing it to the ST801, saying that both have one of the quietest found in any SLR camera.

Comments on some large gaps between the available numbers that the LED display can show, lead to a test later in the article calculating at which points does the shutter’s infinitely variable speeds make a jump on the LED display. Another potential con that the camera lacks any manual speeds below 1/60 are quickly addressed by saying that the manual speeds are also mechanical, meaning they can be used with a dead battery, something that few electronic shutter cameras could do.

Interestingly, the film cassette window on the back was praised for the ease at which you can tell if film is in the camera, but less so about reading what type, as it wasn’t yet typical for film makers to imprint identifying information on the part of the cassette seen through the window. This feature would soon be adopted by many other camera makers, including Kodak, and by the 1980s, most film could be identified this way, just not in 1974.

The overall tone of the ST901 review remained positive throughout, with the editors declaring that “the field test of the ST901 proved to be one of the most enjoyable we’ve experienced in a long time.” A second declaration was that you will not find a more advanced auto SLR in the immediate future, suggest this was a camera for consumers to take seriously.

The Fujica ST901 was clearly a technological behemoth, and one that checked off all the right boxes for the era in which it was made, but models like the ST901 and those by it’s competitors only delayed the inevitable. The era of M42 screw mount SLRs was drawing to a close. It is not clear exactly how long the camera was in production, but in 1978 a simpler model called the AZ-1 would be released, retaining the same aperture priority automatic exposure and support for the same lenses, but without the LED display, and a greater use of cost cutting plastics.

Today, cameras like the Fujica ST901 have appeal to collectors and users alike. For the collector, you get a relatively recent camera that is historically significant for it’s use of a number of new technologies, and for the user, it’s a camera that is just as capable today as it was when it was new. Whether you are new to film, or a grizzled veteran, these cameras are excellent shooters and when found in good condition are just as good as anything else out there, screw mount or not.

My Thoughts

One of my earliest loves in film photography were screw mount Pentax SLRs, specifically the original model and the Pentax Sv. Although I had access to a variety of other mount SLRs, I quickly built up a pretty decent collection of Takumars and M42 lenses by other companies and wanted to continue exploring all of the different options out there.

When I got my first Pentax ES II and saw that automatic exposure was possible with a screw mount SLR, I was intrigued. Although that camera wasn’t in the best working order, I reviewed it and liked the results I got. Next came the Chinon Memotron CE II which like the ES II had some conditional issues, but once again delivered the goods in terms of image quality.

From there, my attention was drawn to the Fujica ST901, another screw mount SLR with automatic exposure and a really neat red LED display in the viewfinder. Unlike the Pentax and Chinon models where I was able to find cheaply, getting a nice ST901 with the correct lens proved to be a challenge. Very few ever showed up for sale, and when they did, they were offered for much higher than I was willing to spend and eventually I lost interest in pursuing one and the camera went to the back of my mind.

Fast forward a couple years to last fall and I stumbled upon this ST901 which looked to be in great condition and had a price I was comfortable with. As an added bonus, it came with the uncommon 55mm f/1.6 Fujinon lens which supported the camera’s AE function. The camera arrived in mostly good condition. The filter ring on the lens had taken a hit or two over time so I did the best I could to straighten it out, and also the focus was a bit stiff, but otherwise the camera worked well.

The ST901 was Fuji’s top of the line model upon it’s release and it’s quality is evident when holding it. While not quite as tank like as say a Nikon F2, with the Fujinon lens, the camera weighs a not insignificant 830 grams. As is the case with most mid 1970s SLRs, the camera’s body is a mix of metal and composite materials. Although the top and bottom plates have the appearance of being metal, I’m not totally convinced it’s not some kind of man-made material like Canon was already using at the time. Whatever amount of plastics this camera has in it’s construction, it certainly does not feel cheap.

Up top, the ST901 looks like most other 1970s SLRs with a folding rewind knob on the left, flash hot shoe above the prism, shutter speed dial, cable threaded shutter release with shutter lock collar, rapid wind lever, and a very large and easy to read automatic resetting exposure counter.

Although the location of the shutter speed dial is in the typical location for an SLR of this era, closer look at your options is a bit different than most. For starters, your choices of manual speeds are limited to speeds 1/60 through 1/1000 plus Bulb. There is no way to select slower speeds than 1/60 as the designers of this camera clearly assumed that most people would use it in Automatic mode. As an added bonus, the manual speeds are also mechanical and work with a dead battery, which is a feature that was increasingly uncommon on electronic shutter cameras of the era.

With the dial set to the orange AUTO mark, exposure compensation from +2 to -2 can be chosen to alter the exposure as needed. Under normal operation, the shutter speed dial is locked in the AUTO position, preventing you from accidentally disabling the automatic metering system or selecting an EV +/- number. To rotate the dial away from AUTO, you must press and hold the chrome lever above the shutter speed dial towards the back of the camera while simultaneously turning the dial.

The bottom of the camera is bare, with only the rewind release button and the 1/4″ tripod socket, which is strangely offset to the side which would throw off the balance of the camera when mounted to a tripod. It seems odd that with such an empty bottom plate, Fuji didn’t centrally locate it beneath the lens mount.

The back of the camera is unusually interesting as the Fujica ST901 was the first camera to have a see through rectangular peep hole on the door allowing you to see what kind of film is loaded into the camera. This would become a standard feature on nearly all 35mm cameras in the 1980s, but was quite uncommon for a camera released in 1974.

The back is also where the compartment for the 6v PX28 battery and a small lever for activating the viewfinder blind which is used for long shutter speeds to avoid light from entering the viewfinder and causing erroneous readings. The use of a PX28 battery means there is no worry about having to adapt the voltage from a mercury battery to get correct exposure readings.

Open the film compartment with a firm tug of the rewind knob and the right hinged film door swings open to reveal a pretty ordinary film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed and multi-slotted take up spool. The film pressure plate is large and covered in divots, and there are rollers on the inside of the door to aide in smooth film transport. Notice the foam gasket on the inside of the door where the rectangular peep hole is. Strangely, this foam had not degraded like the rest of the door seals which I had to replace. I used adhesive backed black felt for the door seal and black cotton yarn for the door channels.

The side profile of the camera is nicely balanced top to bottom and front to back. With the 55mm f/1.6 Fujinon lens, the camera has a neutral weight distribution and does not feel front heavy. On the left side of the front plate are the PC flash sync ports for FP and X bulbs giving good compatibility to the latest hot shoe flashes, along with any corded flashes that an owner might have had when buying this camera new.

The 55mm f/1.6 Fujinon lens has large and easy to read color coded aperture marks and a depth of field scale on the inner rings. The focus ring has markings in both meters in white and feet in green. Nikon SLR fans will feel right at home with the Fuji’s arrangement of controls which many Nikon critics point out is backwards from most other camera makers. Where most lenses will have the largest aperture on the left and the smallest on the right, the Fujinon has f/16 on the left and f/1.6 on the right. The lens also focuses left to right from infinity to minimum focus instead of the other way around like most other lens makers. To be honest, this arrangement of controls doesn’t bother me either way, but some people make a big deal about it, so if this is one reason you don’t like Nikon SLRs, you might not like the ST901 either.

The Fujica ST901 uses the “universal” M42 screw mount which means it’s lenses go on like any other screw mount camera….is what I would say if the ST901 was just any other M42 camera.

The reality is, that although you can physically mount any M42 screw mount lens to this camera, only with the correct Fujinon M42 lenses will the automatic exposure feature work. The reason for this is an indexing tab around the perimeter of the mount near the 2 o’clock position of the lens mount is used to set the maximum aperture of the lens. In order for this feature to work though, a second pin, near the 9 o’clock position acts as a locking tab which clicks the lens into place when screwing it on. This means that the ST901 has a lens release button that must be pressed before you can unscrew the lens, just like any regular bayonet lens SLR. When screwing the lens back on, you’ll feel and hear an audible click as the pin locks the lens in place when fully mounted. This not only gives a positive feeling of security when mounting and dismounting the lens, but it also allows the automatic exposure system to work correctly.

The ST901 is in rare company as one of the very few M42 screw mount SLRs capable of auto exposure, but one feature that sets it apart from it’s competition is the red 8-segment LED display in the viewfinder. The most prominent camera to use a similar digital LED read out was the Canon A-1 which came four years later. The Fuji’s isn’t quite as elaborate as the Canon’s as it only shows the selected shutter speed, but to even see that is really cool. For me, the display gives a sense of nostalgia as it reminds me of old Casio or Motorola calculators I had as a kid, but back when this camera was new, it likely evoked the feeling of a futuristic camera.

In the Modern Test review of the ST901 earlier in this article, quite a bit of time is spent on the various speeds that the camera uses at each of the displayed LED shutter speeds. Although the auto exposure metering system offers infinitely variable shutter speeds, the LED display will only show a total of 14 different speeds, strangely omitting 125 and instead showing 100, even though that is not a speed you can choose manually. The article also cautions you that in extremely low light, the meter takes a second or so to settle on a reading.

In the images above, I show three different shots through the viewfinder, some in an out of focus to better see the focus aides in the center. The red LED display only works when the camera is in auto exposure mode. Selecting speeds manually will turn off the display.

The viewfinder is extremely bright, thanks to a micro Fresnel ground glass with split image and microprism focus aides. The curved wheel will indicate an orange “A” when the camera is in auto exposure mode, anywhere between -2 and +2 to show different exposure compensation selections, or each of the camera’s manual shutter speeds when those are selected. Although not as helpful as the full information viewfinders that would become common in SLRs not even half a decade later, the implementation in the Fujica ST901 is very cool.

Overall, this is a camera that represents an odd mix of being the end of an era with it’s outdated M42 screw mount, but also ushering in new technologies like Aperture Priority Auto Exposure, a Silicon Photo Diode meter, a futuristic red LED viewfinder display, and one of the first implementations of the familiar film cassette peep hole on the film door. Shortly after the ST901’s release, Fuji would switch to an all new bayonet mount and release cameras consistent with what everyone else was making, but in doing so, lost their edge as an innovator.

Repairs

I was fortunate to come across this camera in good working order, so it didn’t need any repairs other than the usual light seal replacement, but in my research for this article, I found some repair notes that someone had made. I do not know the name of whoever created this, but at the bottom of each page it says ‘SPT Journal’, so if that is you, please let me know so I can give you credit. Reposting here for the benefit of anyone who wants to attempt to repair theirs.

My Results

For the first roll in the Fuji ST901, I figured I would keep it in the family and loaded in some fresh Fuji 200 and took it out shooting on a warm autumn day last year. There was some road work being done on a bridge near my house that I took a walk to and shot some photos of the construction. The Fujinon f/1.6 lens mounted to the camera was optically excellent, but had a really stiff focus ring, so I didn’t want to shoot too many closeups, which ended up working out fine considering the distance needed to safely shoot workers doing their thing.

I ended that roll with a couple light leaks which I resolved by replacing the light seals and then loading in a second roll of bulk Kodak TMax 100 which I am also including in the gallery below.

I’ve reviewed quite a number of Fuji/Fujica cameras on this site, and other than the leaf shutter Fujicarex II, the ST901 is my first true Fuji SLR. I have regularly gotten excellent results from other Fuji cameras, from the half frame Drive to the medium format Super Fujica-6, so I assumed that the general quality of the company’s lenses would apply to their SLRs.

Yep, they look good!

As I expected, the image quality from the Fujinon’s lens was superb. The deep blue and purple lens coating did wonders for color accuracy on the run of the mill Fuji 200 and produced excellent contrast in the black and white images. Sharpness is excellent corner to corner, and there’s little to no softness or vignetting near the corners. This is especially impressive considering the strange make up of the 5-element f/1.6 lens. I do not know of any interchangeable SLR lens with an f/1.6 maximum aperture, and considering that most lenses f/2 and faster have 6 or 7-elements, to see one this fast with only five was a bit strange to me.

Using the camera was a pleasure. For the entirety of the first roll, I left the camera in Auto mode and changed aperture based on lighting conditions and looking at the entire roll, everything came out properly exposed. With the second roll, I used a combination of auto and manual modes with Sunny 16. The user experience of the ST901 was excellent, so much so in fact, that at times I forgot I was using a screw mount camera. While the ST901’s lens mount was first used in 1948, twenty-six years prior, it did not hamper the operation of the camera whatsoever.

Compared to other M42 cameras with automatic exposure like the Pentax ES II or Yashica Electro AX, there is no need to manually stop down the lens in auto mode. With the Pentax, turning on the meter automatically stops down the lens, darkening the viewfinder. The Yashica is similar, but always has the lens stopped down, unless you press the manual override button on the front face of the camera. With the Fujica ST901, the viewfinder remains bright up until the exact moment of exposure.

Of course, with this convenience comes the requirement of special lenses. Only when using Fujinon lenses with the necessary coupling will you benefit from the wide open aperture. Without that special coupling, any M42 screw mount lens by any other company (even Fuji) can physically be mounted to the camera, but the camera will only work in either stop down mode or manual, just like the Pentax and Yashica.

The Fuji ST901 is a strange camera to rate. On one hand, it’s use of an advanced meter, automatic exposure, and some features not seen on any other cameras suggests it should have been a revelation, but it’s use of the M42 mount unfairly groups this camera with what was then a growing number of discount and uninspired cheap M42 SLRs. In use, the ST901 is fantastic. It has a great viewfinder with a cool LED display, an accurate meter, and all the features you could want in a mid 1970s SLR, and when found in working condition, is an excellent camera to use. They didn’t sell in large numbers though, so finding one in working condition today is a challenge, but if you do manage to get your hands on one, you’re likely to really enjoy using it.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Fujica_ST901

https://www.35mmc.com/30/11/2018/fujica-st-901-review/

http://cjo.info/classic-cameras/fujica-st901/

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=10227

Mike, thanks for another insightful review.

I’m not unfamiliar with Fujica film cameras. I still have my mint ST705W coupled with the excellent f3.5/35mm lens and which I last used in the early 1990’s, and an AX-3, which I picked up extremely cheaply in the days before film started its revival and the silly increase in prices. The later ST801 and this ST901 went under my radar when my brief sojourn with M42 came to an end, but your review piqued my interest about the ST901, particularly how Fuji addressed auto exposure with the somewhat dumb M42 mount, and the v/f display. The collector in me can be a sucker for cameras that occupy an historical point in their evolution, and this Fuji ticked the right box. So, immediately following your review, I was on ebay and won an auction for a body only and for what has turned out to be one in pristine condition and fully working.

I’d suspected, or rather I’d hoped, in that not having an EBC lens that the 35mm lens’ aperture coupling tab would be compatible with the 901’s mount, and it turns out my hope was rewarded. This highlights that some earlier non-EBC lenses will fully couple, but one needs to be able to have a good close-up view of the mount to spot the tab and the indent for the lens retaining pin.

I love the digital shutter speed read out, although the left-side positioned Auto indicator with +/- indicators, or shutter speed when in manual mode, can be very hard to see in anything other than good lighting. But the screen is large and bright and is easy to focus. It’s a fine camera, and I am pleased to have one in pristine condition, but still I am left wondering. OK, it has aperture priority auto, and stop down metering, but where does it fit in Fuji’s range of cameras that came before? If we take the ST705W, for example, how does the ST901 fare? ST705W has a full range of speeds from 1sec to 1/1500, and the camera will meter in full aperture mode with the same lenses as the 901. The 901 meters in full aperture mode, and right down to 20 secs, in auto or in stop down mode, but it can not meter at all with its more limited range of manual speeds from 1/60 to 1/1000.

Accurate exposure compensation can be dialled in with the 901, whereas with the 705W exposure compensation can only be guessed, and from experience, by setting the swing needle to a position above or below the centre point. Then for this comparison only, we come to the 705W’s killer feature – it takes a motor winder. The 901, and 801 both lack this capability. So, rather than making the 705W obsolete, I believe we should view it, along with the 801, as Fuji giving the photographer a choice, as each has something to offer to differentiate themselves.

Terry, glad to help other people spend their money!

As you noted, that some non EBC lenses will couple fine with the 901’s meter. In fact, the f/1.6 Fujinon lens I used is not an EBC lens and it works fine. I do not know of a surefire way though to tell if ALL Fujinon M42 lenses will work.

Your insight into where the model might fit into Fuji’s lineup is very well thought out. As you said, the 705W has some desirable features the 901 lacks, most notably metering in manual models. They could have very easily used the LED display to show a plus or minus sign to work on a match needle like mode. I don’t even mind that manual speeds below 60 aren’t an option as that’s not an issue for people with the Pentax ES II.

Still, it’s a very cool camera with lots of new technology for the time and one that I am happy to have in my collection, as from how it sounds, you are too!

Mike, you’re spot on with your assessment of my overall response to the 901. It excels at what it does, that invariably the “what if…?” questions arise. What if it metered in manual mode, what if it had a motor winder, and so on. But then we get into arguing for a wish list of what our personal perfect camera would be.

As for the lens issue, I believe it is easy to tell which Fujinon lenses are fully compatible with the 705w, 801 and 901. I say “easy” but this assumes you have a Fujinon M42 in the hand or a good quality closeup image of the lens mount. I have an early f1.8/55 all metal Fujinon which comes in its basic form with just the aperture actuating pin, a feature common to all M42 lenses including, for example, the f2/58 Biotar on my Contax F, but not the very earliest which lack even the spring loaded aperture as apertures are set manually on the lens. (Incidentally, this is a very good reason for anyone interested in an early Contax slr to consider the later F model. Historically, not the first, but arguably the best.)

The two “giveaway” features are the small cutout into which the spring loaded pin in the camera mount locates and locks the lens in place and which Fuji calls the “Safety Lock”, and the small fixed protrusion on the aperture ring that engages the meter setting ring around the mount and which determines the maximum aperture of the attached lens and which also transmits to the exposure meter the aperture in use. Without both of these features a lens can only be used in stop down mode.