This is a Hanimex Hanimar, which is the Australian export version of the Sarabèr Finetta 88, a 35mm viewfinder camera made in Goslar, West Germany by Finetta-Werk Goslar starting in 1953. The Finetta 88 was the final model in a confusing line-up of Finetta cameras that were produced between 1948 and 1954. This model has a proprietary bayonet lens mount and a four-speed rotary shutter, contained in a large and mostly hollow aluminum body. Despite having the appearance of heft, the Finetta 88 was a simple camera that was cheaply built and likely sold poorly as few exist today. Export Hanimars are identical to the original Finetta 88 and differ in name only.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 45mm f/2.8 Finetar coated 3-elements

Lens Mount: Finetta 88 Bayonet

Focus: 2.8 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus

Shutter: Behind the Lens Rotary

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and PC Port Flash Sync

Other Features: None

Weight: 472 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/finetta.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Finetta 88 and it’s Australian rebadged Hanimar is an interesting looking camera with compelling set of features, designed by a little known company from the early 1950s. Featuring a beautifully designed mostly aluminum body, the Finetta 88 has an interchangeable lens mount, metal blade four speed shutter, and pretty good ergonomics. Sadly, the discount origins of this camera show, as it has one of the worst lens mounts I’ve ever used, the aluminum body is prone to heavy oxidation and it is difficult to find these in working order. The images it makes aren’t bad, but aside from it’s good looks, is very forgettable compared to a huge number of competing contemporary cameras. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

The name Sarabèr is not well known today by collectors, but for a very short period of time after World War II belonged to a series of popular, but also confusing cameras first called the Finette, and later Finetta.

The name Sarabèr is not well known today by collectors, but for a very short period of time after World War II belonged to a series of popular, but also confusing cameras first called the Finette, and later Finetta.

The man behind the Finetta was Piet (Peter) Sarabèr, who was born in 1899 in Saarland, Holland. Prior to World War II, Sarabèr studied engineering and worked as an electrician. After the Nazis conquered Holland, Sarabèr’s skills as an electrician were deemed valuable and was brought to Germany to help with the war effort. By 1940, Sarabèr was located in the Dresden area and was employed by Korelle-Werke KG

While working for Korelle, Peter would meet and marry his wife Elizabeth. Immediately after the war, he and his wife would relocate to Goslar, Germany and would setup his own company, first making small electrical devices such as microphones and other types of audio and photographic equipment.

In 1947, Peter Sarabèr would collaborate with a former Voigtländer technician named Helmut Finke on a new camera called the Finette. The Finette was a simple viewfinder camera with a Bakelite body, making it sturdy and affordable. Shortly after it’s release in 1948, the relationship between Sarabèr and Finke fell apart as it was discovered that Finke was shopping around his design to other companies. As a result, the name changed to Finetta and the design was updated.

In 1949, Sarabèr would hire his friend Rudolph Trentsch whom he had met while working for Kochmann to help him advance the design of his camera. Trentsch was both a skilled engineer and designer and would be entrusted with the company’s future. Now headed in the right direction, the new company would be known as Finetta-Werk Goslar and would relocate it’s factory to a former military barracks building called the Dom-Kaserne.

Sarabèr shared the building with a company that helped retrain people injured during the war. From this company, Sarabèr hired 60 people, mostly women, as he believed that women had better dexterity than men, which would help them in assembling cameras.

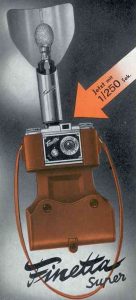

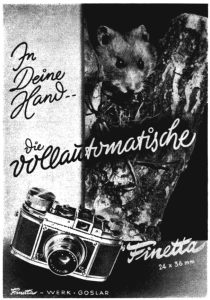

By the early 1950s, Finetta cameras were growing increasingly advanced. Although still viewfinder only, the bodies were now made of metal, with better shutters, and as of the Finetta IV D, now featured interchangeable lenses. With the infusion of knowledge from Trentsch and others he hired, in 1951, a camera called the Finetta Super would make it’s debut.

The Super retained the same interchangeable screw mount from the Finetta IV D, but featured a redesigned and more attractive top plate, but also a flash hot shoe. Although hot shoes had existed on cameras prior, the feature was still very unusual. No doubt owing to Sarabèr electrical engineering background, together with a Finetta flash unit, the camera offered direct contact synchronized flash at all speeds.

The very early 1950s saw great success for Finetta-Werk Goslar as sales were strong and the factory was churning out new cameras daily. With his contacts in the photo industry, Rudolph Trentsch attracted the talents of Herrn Höhlemann and Karl-Heinz Reich, both camera designers who would start to work on what would become the most advanced Finetta yet.

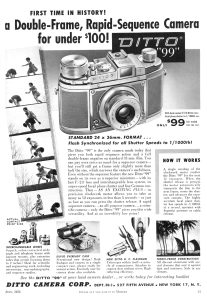

This new camera was called the Finetta 99 and would feature an all new, and much lighter die cast aluminum body. It retained the flash hot shoe from the Finetta Super, but inside the body was a new focal plane shutter with speeds from 1/25 to 1/1000. The film transport was motorized via a tensioned spring, wound up using a large knob on the camera’s top plate. A new, and larger bayonet lens mount was created that was faster to use than the screw mount found on previous models, finally, at least eight new lenses, ranging in focal length from 35mm to 105mm, including a 45mm f/2.8 macro lens built by Staeble-Werk Germany.

The Finetta 99 made it’s debut in 1952 and was quite an advanced camera, with interchangeable lenses, full flash synchronization, a focal plane shutter with top 1/1000 speed, and motorized film transport. In 1953, a second version called the Finetta 99L was released that added a slow speed governor, extended the slowest speeds down to 1 second.

When sold in Europe, the camera retained it’s original Finetta 99 name, but it was also exported to the United States under the name Ditto 99 and sold for $99, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to just under $1100 today.

On paper, the Finetta 99 was a rousing success, but like all advanced cameras made by small companies, perhaps the innovative features were a little beyond the capabilities of the company as examples of the camera were plagued by reliability issues. The wind up motorized film transport was prone to jamming, the centrally located focal plane shutter was unreliable, and although the camera was priced favorably compared to other German cameras of the era, sales were sluggish.

In an effort to continue bringing in money in an increasingly competitive camera market. in 1953, a simplified camera called the Finetta 88 was released. Although featuring the same body and chassis, almost all of the innovative parts of the Finetta 99 were removed. Gone was the motorized film transport, replaced by a manual knob, the focal plane shutter was replaced by a simple two blade metal shutter, even the flash hot shoe first introduced on the Finetta Super was removed. Strangely, the camera retained a bayonet lens mount, but it wasn’t the same bayonet lens mount from the Finetta 99, or the screw mount from the earlier cameras. The new 3 claw bayonet on the Finetta 88 was smaller in diameter and required new lenses to work.

Only three lenses were made for the Finetta 88’s lens mount:

- Finetar 43mm f/4 Close Focus

- Finetar 45mm f/2.8

- Finetar 70mm f/6.3

The Finetta 88 was sold in Germany and exported to the UK and Australia, but does not appear to have been sold in the US. When sold in Australia, the imported Hanimex rebranded the camera as the Hanimar, although nothing else changed from the Finetta 88.

Although a simpler and more reliable design, the camera did little to alter the financial struggles the company was having. A short partnership with Russian/American camera designed Jacques Bolsey in creating the Bolsey 8, an ultra-compact 8mm camera provided some financial relief, but it wasn’t enough and in February 1957, the company filed for bankruptcy. Production continued on a limited basis until November of that year, at which point the factory shut it’s doors, never to open again.

After the failure of his company, Peter Sarabèr wound bounce around the photo industry, working for companies like Minox, Bilora, and a company that made binoculars. Sarabèr would eventually pass away in 1985 at the age of 86.

Finetta/Ditto 99

I had wanted to review the Finetta 99 for quite some time, but in a couple years search, my best option was this non working Ditto 99 that came to me with a bad shutter. While scouring the usual sources for a better example, I came across a working Finetta 88 for a good price so I figured I would just test that, and make mention of the non-working 99 I had.

The Finetta 99 dates from before the 88 and was the companies most ambitious model. It has a unique three claw bayonet that is not the same used on the Finetta IV or the later Finetta 88. Although a variety of lenses were made for it, they were all made by B-list lens makers. I am not aware of any Zeiss or Schneider lenses made for these cameras, suggesting the optical performance was probably good, but not remarkable.

It is strange to me that a camera would be designed with premium features like an interchangeable lens mount, focal plane shutter with top 1/1000 shutter speed, motorized film transport, and a flash hot shoe, yet it is scale focus only. No rangefinder version of this camera was ever made, nor did I find any evidence that one was planned. I wonder who the target customer this camera was built for.

The Finetta 99 came first, but when the Finetta 88 was created, it used the same basic body, but little else was the same. Gone were the motorized film transport, focal plane shutter with speeds from 1 to 1/1000, and flash hot shoe with adjustable sync delay.

Starting with the body covering, the Ditto 99 has a light gray body covering that has the same “rope-like” pattern as the Finetta 88. The shutter speed dial is no longer on the front and is instead on a single dial on the top plate with speeds from 1/25 to 1/1000 plus Bulb. A variant called the Finetta 99L had additional slow speeds down to 1 second. Up top, in addition to the larger wheel for tensioning the spring motor drive, there is a relocated flash sync port and the contacts for the flash hot shoe. The baseplate has the same circular door lock with integrated 1/4″ tripod socket, but has an additional wheel for relieving tension on the spring wound motor for rewinding the film.

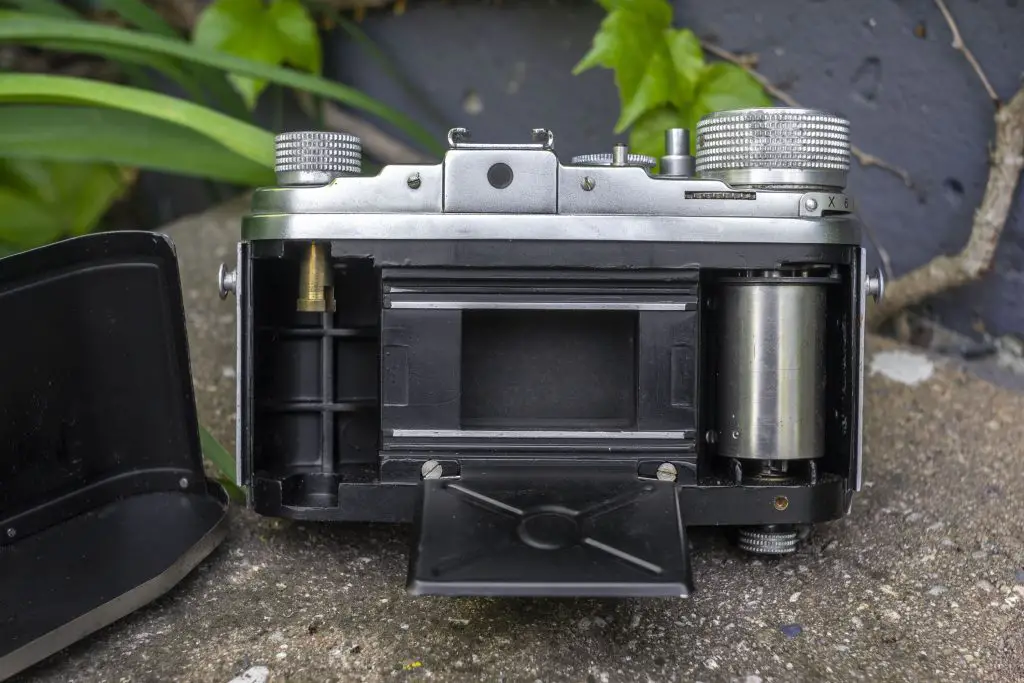

Around back, other than the color of the body covering, the two cameras look the same, Taking the back off, and things are very different. Inside the film gate, you can see the cloth curtains for the focal plane shutter. Unlike most focal plane shutter cameras, the curtains are closer to the back of the lens, rather than up against the film plane. The large take up drum is not painted and looks to be made of stainless steel. It also has a different method for attaching the film leader. The pressure plate is still a folding design, but unlike the Finetta 88 which is hinged near the top, this one is hinged at the bottom. This makes no sense to me as the bottom method seems easier to work around. Finally, the lens mount is completely different. Not only is it larger than the one on the Finetta 88, it does not attach with a bayonet. Instead, there are two spring loaded clasps on each side of the lens mount that grip a notch around the entire perimeter of the lens. To detach the lens, two spring loaded posts, near the 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions around the mount must be squeezed together to release the lens. Putting the lens back on is very simple as you simply line up a notch and press it back into position. This type of lens mount is far superior to the cheap bayonet on the Finetta 88. Why this was changed is a huge mystery to me.

The first image above shows another angle of the two posts used to remove the lens from the camera. A sliding dial around the right edge of the top plate beneath the dial for winding the motor is used to change the flash sync delay for different types of flash bulbs. Below the flash sync and on the same location on the opposite side of the camera are posts for attaching a neck strap, a feature missing from the Finetta 99. Below the engraved Ditto 99 logo on top of the viewfinder is the electrical contact for the flash hot shoe, which was first introduced on the Finetta IV.

In his review for the Finetta 99 posted on Casual Photophile, Cheyenne Morrison raves about the camera, saying it “epitomizes everything he loves about vintage cameras”, a claim I had hoped to test myself.

Having handled one, I can say they certainly are neat, look unlike anything else ever made, and with the motorized film advance, check off many of my same boxes too. But having shot the 88 and handled a non-working 99, I don’t know if I would have been so complimentary as Cheyenne. These were discount cameras that clearly were not built well. The entire reason for the Finetta 88’s existence is because the Finetta 99 sold poorly, largely due to poor performance. The lens mounts on these cameras are made of thin sheet metal and are difficult to get on and off. The focal

My Thoughts

I had been searching for a working Finetta 99 for quite some time when I finally came across this working Finetta 88 and coming to the realization that I didn’t want to wait any longer, I decided this would be the Sarabèr camera that I would review.

Both the Finetta 88 and 99 share the same basic body, which although attractive seems strangely thick. The Finetta 99 uses a cloth focal plane shutter that is about halfway between the back of the lens and the film gate. Unlike most focal plane shutters, this means there is a gap between the actual curtains and the film. I don’t know why this was done, nor do I have an advanced enough understanding of optics, but I have to think that the reason nearly every focal plane shutter is nearest the film plane is because it needs to be near where light converges to make an image. Does having the curtains forward of that point make a difference in the performance of the camera? I have no idea.

Whatever the case, the location of the shutter in the Finetta 99 and that the Finetta 88 shares the same body with a simpler leaf shutter probably explains why it is so thick. The camera’s body is made from aluminum which is a good thing because I feel that if this was a solid brass camera, it’s size would have pushed it’s weight to portly numbers.

Up top the thickness of the camera is quite apparent with the comically small lens mounted up front adding very little to the overall depth of the camera. A rather ordinary rewind knob is off to the left, but unlike most rewind knobs, does not lift up to make rewinding easier. On this camera, rewinding a roll of film must be done with it flush against the plate.

In the center, directly above the viewfinder is the accessory shoe and an engraved Saraber Goslar logo and serial number. This logo is a bit confusing because as far as I can tell, by the time this model was released the name of the company was Finetta-Werk Goslar.

Off to the right is the exposure counter, cable threaded shutter release button, and large film advance knob. The knob has the same diameter as the one from the Finetta 99 but doesn’t stick up as high. This camera does not have a motorized film transport so advancing the film simply requires you to turn the knob until it stops. As a benefit though, the large size of the knob makes advancing the film quick and easy. The exposure counter must be manually reset after loading a new roll of film and is additive, showing how many exposures were made on the roll of film.

Around back we see a large swath of body covering across the entire film door. Whatever the body covering is made of, feels pretty durable and shows no signs of cracking or peeling on either my Finettas 88 or 99. The circular eyepiece for the viewfinder is centrally located, and a knurled wheel to the right, just behind the exposure counter is used to reset the exposure counter back to 0 after loading in a new roll of film.

The bottom of the camera mirrors the thick shape of the top plate and has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket and a circular wheel for unlocking the film door around it. Opening the camera requires you to rotate the wheel clockwise to open, and counterclockwise to close.

The back and bottom of the camera come off as one single piece revealing the film compartment. Film transport is from left to right onto a very thick single slotted take up spool. Not shown in these pics is beneath the film gate, embossed into the metal are the words “Made by Finetta Werk-Germany”.

A chrome hinged film pressure plates is hinged at the top of the film gate and must be swung up when loading film into the camera. The pressure plate can hold itself in the up position which is a nice touch as that means you don’t have to keep holding it while loading film. Attaching film to the take up spool is a bit strange as the “slot” isn’t really a slot, as it’s more like a chrome hump that you must fold the leader underneath while simultaneously rotating the spool with your finger to make sure it stays in place. I had my doubts about how well this worked, so when I loaded film into the camera, I used a piece of tape to secure the leader to the spool.

From the side, once again we see the abnormal thickness of the body combined with the shallow depth of the lens. At first glance, you would be forgiven if you thought that perhaps the lens was collapsible and must be extended before it could be used, but that is not the case. The Finetta 88 lacks any sort of tripod lugs or loops, meaning that you would have had to use the original ever ready case if you needed a neck strap.

Up front, we see the 45mm Finetar lens and the three claw bayonet lens mount that is unique to this one camera. The lens mount is one of the poorest designed I’ve ever seen on a camera as its simply a piece of sheet metal in the same of a bayonet. Both the mating surface on the body and the claws on the lens are simple pieces of metal that bend easily. When I first got the Finetta, the lens was very wobbly, causing me to think that perhaps it wasn’t mounted correctly. I discovered the claws were just out of shape, so I was able to bend them back using needle nose pliers, but this is something I would think that all Finetta 88s would suffer from.

Below and to the left of the lens mount is the shutter speed dial. With only four speeds from 1/25 to 1/250 plus Bulb, you won’t get as much exposure flexibility as the Finetta 99 offers, but it is good enough for most general purpose outdoor photography.

Around the front lens element is a black ring for controlling the lens diaphragm. The ring lacks click stops and has indicated marks for f/2.6 to f/16. Focus is controlled by rotating the entire ring around the perimeter of the lens.

The viewfinder is a straight through optical design offering views for two different focal lengths. Rather than using some sort of projected or painted frame lines, the Finetta takes the clever approach of having a transparent gray plastic frame around the central image which when including the gray frame, represents a 45mm focal length. Without the frame, looking through just the central clear part, you get an approximate focal length for the optional 70mm Finetar f/6.3 lens that was available. Although simple and effective, this implementation doesn’t make a lot of sense as very few people would have had the 70mm telephoto so you end up always having to use the information coming through the gray plastic when composing most shots.

Both the Finetta 88 and 99 and their name variants are curiously designed cameras with good looks and an interesting feature set. The Hanimar reviewed here is scaled down from the original Finetta 99, but in their effort in making a less expensive camera, did it’s designers go too far? There are many ways in which the camera’s discount roots show, but how much do they affect the images the camera can make or the shooting experience. Keep reading…

Repairs

The Hanimar came to me in mostly working condition, with it’s only fault that the take up spool seemed to spin freely from the film advance knob. I could turn the knob to cock and fire the shutter, but with film in the camera, there wasn’t enough tension on the take up spool to transport film through the camera.

After playing around with it for a short while, I noticed a small screw near the bottom of the take up spool, near the film leader attachment. On a whim, I got out my Wiha screwdrivers and tightened that screw and it worked! The take up spool was now securely connected to a shaft underneath that was part of the film advance knob! If you run into a camera with this same problem, try tightening this screw!

My Results

When it came time to test the Hanimar, I had some concerns about the two slower speeds, so I wanted to stick to 100 and 250. Wanting a film that would afford me a wide range of latitude, I went with Kodak TMax 100. This is my go to film for cameras with questionable shooters that I’ll likely stick to a single shutter speed throughout a roll. It also helps that I really like the images I get from TMax 100 as I’m a sucker for fine grain medium contrast film.

I know that some people skip through most of my reviews and go straight to the sample images at the bottom. If that’s what drew you to this review, then that’s fine with me! I hope you enjoy the images. But, if these images and my thoughts on them are the only things you read from this entire review, you are likely to walk away with an impression of the camera that’s very different than the one I have.

You don’t need me to tell you these images are pretty good. Sharpness is what I’d expect from a premium three or four element mid century German lens. Contrast is good and exposure is even across the frame. I do see some softness and vague out of focus details near the edges, but nothing that bothers me for what was at the time the discount version of a camera that never sold for a lot of money in the first place. After looking at these images, I debated about whether I should shoot a roll of color through it to see how it would perform, but I honestly didn’t think it would change my opinion of the camera.

I didn’t like the Hanimar. Yes, it makes pretty decent images, and yes, it does look pretty. The large diameter of the film advance knob is actually quite nice to use, and even though the shutter is limited to only four speeds, they are the four speeds I am most likely to use. Much like the Kodak Signet 35 which also only has a four speed shutter from right around the same time as this camera, you don’t always need a wide range from 1 to 1/1000 seconds to make good photos.

Where this camera fails to excite me is both in it’s construction and execution. There are so many simple things that the designers of this camera could have done to make it much better. For starters, the camera is very rough to use. And I don’t mean rough as in, this camera needs a CLA…you can tell from the rough edges of the metal in the film compartment, how the pressure plate is constructed, the ease at which the metal oxidizes, and the various controls of the camera, this was a low rent camera. The lens mount is one of the worst I’ve ever used, feeling extremely cheap and not likely to hold the lens securely to the camera. Even more confusing is that the lens mount on the earlier Ditto 99 is much better. Heck, even a screw mount like that from the Finetta IV would have been better. Why anyone would give this the company’s third lens mount in three cameras is just plain strange.

I didn’t hate the viewfinder, and actually thought the tinted edges to differentiate between two different focal length lenses was a good idea. But it doesn’t make sense that you have to use the much darker part of the viewfinder for either of the two standard lenses and only the bright part for the telephoto when I’d predict that 99% of the people who ever used this camera never used the telephoto. Had the Finetta had a wide angle and a standard lens, the system designed here would have made more sense as you’d only use the tinted part the few times you had the wide angle mounted and the bright part for everything else. In it’s current design, it’s almost as if the designers thought people would use the telephoto the most. It is difficult to wrap your brain around the fact that with the 43 or 45mm lenses, the bright part represents only a cropped image of what the lens sees.

I keep coming back to this, but the lengths at which Finetta-Werk crippled this camera compared to the Finetta 99 is bizarre, almost as if they didn’t want anyone to buy it. It has a terrible lens mount, the viewfinder is worse, there’s no strap lugs, the film pressure plate is hinged on top instead of the bottom, and the innovative flash sync feature found on earlier Finettas is gone. Considering Peter Sarabèr’s background as an engineer with a specialty in electronics, you’d think this would be a feature he was proud of and would have wanted to be on this camera.

With the cherry on top being that these cameras struggled with reliability back then and are hard to find in working condition today, this is a very hard camera to recommend. Cheyenne Morrison wrote a glowing review about the Finetta 99 and I suppose that had I had a perfectly working version of Cheyenne’s camera, with it’s cool motorized film transport, better shutter with wider range of speeds, and without all the other little things that were neutered on the Finetta 88, I probably would have liked it more, but despite looking like a scaled down Finetta 99, this is a very different camera.

I won’t go as far as to say I hated it. It does display nice on a shelf and it did make some good photos, which is more than I can say about many other old cameras I’ve tested. I guess my overwhelming disappointment is that I had much higher hopes for it. I really thought this was a camera I was going to like, and I didn’t. Making matters worse is that these cameras are extremely hard to find in working condition, so simply going to eBay and picking up a better one isn’t much of an option.

If you’ve made it this far into the review and have already read Cheyenne’s review of the Finetta 99 and are excited to try out this model, don’t be. If you find one cheap enough and the seller guarantees it will work, you’ll probably be happy with the images, as was I, but nothing else.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Finetta_88

https://simonhawketts.co.uk/2016/11/08/finetta-88-viewfinder-camera/

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/piet-sarabers-finetta-88.466444/

https://cameracollector.proboards.com/thread/8178/saraber-finetta-88

Pretty much agree with you Mike, the difference between this and the Finetta 99 is massive. More importantly I had the version with the amazing Finetar lens, which made up for any shortcomings of the camera. Thanks for the shout out and link. People can see my images shot with the Finetta 99 in the link below.

Yeah, with your nice example and the macro Finetar lens, I likely would have had a very different experience. At the very least, perhaps someone out there looking for the 99, and wanting to settle for the 88 will read this and realize how different they are!