This is KMZ Drug (Друг), a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Krasnogorski Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ) in the former Soviet Union between the years of 1959 and 1962. During it’s development, a prototype of the camera was made called the Zorki 7, but it’s name was changed to Drug, which translates to “friend”, before it went into production. The Drug has a coupled rangefinder and features the Leica Thread mount, accepting all lenses made for the Zorki and FED rangefinders, but adds an all new bottom lever rapid film transport. In addition to the new film transport, the KMZ Drug has a clean and uncluttered interface, not at all resembling Zorki and FED rangefinders which were still in production at the same time.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5 cm f/2 KMZ Jupiter-8 coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: M39 Leica Thread Mount

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with 50mm and 85mm Bright Frame Lines

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/60 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 746 grams, 622 (body only)

Manual (in Russian): https://mikeeckman.com/media/KMZDrugManual.pdf

Manual (HTML Version in Russian): http://www.zenitcamera.com/mans/droug/droug.html

How these ratings work |

The KMZ Drug was an aspirational rangefinder originally meant to be part of the Zorki family, but ended up becoming it’s own camera. With a higher than usual build quality, an innovative trigger film advance, upgrades to the rangefinder coupling, and a viewfinder that eliminated horizontal parallax error, the Drug was a very good camera. Unfortunately, it’s trigger film advance was it’s Achilles Heel as most are found in non-working condition today. If you do happen to get one that works or has been serviced, it is a wonderful camera to use, and is one of my all time favorite Soviet cameras. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

By the start of World War II, the Soviet Union already had an established optics industry with factories in Leningrad, Kiev, and other cities. The struggle with those locations however, was that they were within striking distance of the invading Germans and by the early 1940s, many were either completely destroyed or abandoned by the Soviets.

On February 1, 1942, by order of the USSR People’s Commissar of Armaments No. 63, an old aircraft factory in Krasnogorsk that was previously evacuated a year earlier was established as State Union Optical Plant No. 393, with the purpose of building aerial optical equipment such as scopes and other photographic equipment.

One of the first cameras produced at Plant 392 was the АЩАФА-2 (ASCHAFA-2), a slot hole aerial camera which was used primarily for photo reconnaissance.

In 1946, after the defeat of the Germans, the Soviet Union would claim as war reparations, much of the machinery and equipment from Zeiss plants in Dresden and Jena. At this same time, the factory received the formal name Красногорский механический завод (Krasnogorskiy Mechanicheskiy Zavod) and it’s symbol a dove prism with a ray of light reflecting through it.

The first consumer products manufactured at KMZ were Москва-1 (Moskva-1) cameras. The Moskva-1 was an almost identical copy of the Zeiss Ikonta 6×9 folding camera. The earliest cameras were built using left over Zeiss parts and Compur shutters, making them quite collectible.

Immediately following the war, the KMZ plant bore a large responsibility of re-launching the Soviet camera industry since it’s operations were never interrupted during the war. As the years passed and other factories were either setup or repaired, they were able to take some of the burden off KMZ, allowing them to have a period of increased research and development into new models.

In the next decade, KMZ would produce a number of other optical products including two of the Soviet Union’s most successful cameras, the Zenit SLR and Zorki rangefinder. Other models produced there were the professional Start SLR, the 16mm Narciss SLR, Horizont panoramic camera, and the Iskra 6×6 folding camera.

A total of twelve distinct models of the Zorki would be produced between 1947 and 1980 making it the factory’s most successful rangefinder camera.

Along the way, several variants of the Zorki were produced, some of which are officially considered part of the Zorki family like the KMZ Mir which is a simplified variant of the Zorki 4, but without slow speeds.

Another variant that isn’t typically counted as a Zorki was a rather advanced rangefinder called the KMZ Drug. In the late 1950s, plans were in place at KMZ to replace their less expensive models with more expensive and capable designs. New cameras like the Zenit 3, the Iskra, and a replacement for the Zorki family were designed.

In charge of the Zorki’s replacement was KMZ Chief Designer E.V. Solovjev and a young man named A.S. Dorofeev. The new camera was to have in common the same 39mm Leica Thread Mount of other Zorkis and a similar rangefinder design of the Zorki 4, but nearly everything else was to be different. This was intended to be a fresh start for the Zorki family. The new camera would be revealed in 1958 as the Zorki 7. This version of the camera is considered a prototype and only a very small number of them were made.

Shortly after the Zorki 7 prototype was revealed, the camera’s name was changed to the Drug (Друг) before it’s 1959 release. In my research for this article, I found no information describing why the name was changed, but perhaps the original plans for the Zorki 7 to replace all previous Zorkis were scrapped, and a new name was thought up to keep it separate. Maybe the camera was too good and they wanted it to stand on it’s own separate from the earlier Zorkis, or perhaps someone working at KMZ just changed their mind.

Whatever the reason for the name change, three minor differences were made for the Drug compared to the prototype. A new Vulcanite body covering replaced the cabled leatherette cover, the self timer was redesigned with an activation button added, and the flash sync ports were moved from the side to the rear of the camera.

Compared to other cameras being produced at KMZ, the Zorki 7 had an unusually high build quality. The chrome plating compared favorably to cameras coming out of Germany and Japan, and extra care was taken to eliminate any rough edges on the body and inside the film compartment. Inside the lens mount, the camera received an upgraded rangefinder coupling arm with a wheel on the tip, which was not available on any other Zorki camera and closer in design to the Leica and Japanese Leica Copies.

The shutter, although resembling every other cloth focal plane shutter of the era, was unique to this camera and completely new. Normal focal plane shutters set the gap between the first and second curtain at the instant the shutter is fired. The first curtain starts to open and the second is held back however long is necessary to make an appropriate shutter speed. When the correct gap is reached, the second curtain starts to close and eventually catches up to the first curtain at the end of the exposure. This works fine in many instances, but can sometimes cause uneven exposure near the sides of the image where the curtains are speeding up and slowing down.

In the Drug, a revised timing system allows the shutter to set the gap between the first and second curtains before it crosses the film gate, allowing the gap to be even across the entire exposure, instead of only in the middle. This meant that the Drug should be capable of more accurately exposed images. The curtains themselves were made of silk with a rubberized coating, unlike many other Soviet cameras whose curtains were a lower quality cloth material. Another advantage to this design is that the flash sync is 1/60, which was a full stop faster than the 1/25 and 1/30 sync speeds of other cloth focal plane shutters of the day.

Perhaps the camera’s most unique feature was it’s film advance, which was of a bottom “trigger” design, in which a folding lever sticks out of the bottom of the camera at a 90 degree angle and slides along the length of the base plate to advance the film and cock the shutter. This design was very similar to that used by Leitz in the Leicavit adapter and Canon on their VT rangefinder, first released in 1956.

The camera had a very clean rectangular body, reminiscent of some Japanese rangefinders of the era, and featured a conveniently located front shutter release, similar to Miranda and Praktica SLRs of the same era. Unlike those cameras however, the shutter release could be held down and upon making a full stroke of the film advance, the shutter would immediately fire for fast action shots. The camera’s manual suggests that with practice, up to three exposures per second can be made this way.

The main viewfinder window was centered above the lens with the rangefinder shifted off to the side. By locating the viewfinder directly above the lens, horizontal parallax error was eliminated, only requiring the photographer to compensate for vertical error at close focus. Inside the viewfinder were bright frame lines for both 50mm and 85mm lenses.

When it was released, the KMZ Drug had a lot of things going for it, a clean and modern design, support for one of the most well used lens mounts of all time, above average build quality, and modern features like a coupled rangefinder and trigger film advance, but it didn’t sell well. According to the Russian language book, “Choosing a Camera” by D.Z. Bunimovich, the price of the Drug was stated as 70 rubles. This was greater than other cameras in the same guide like the the Zorki 4 at 61 rubes, Zorki 6 at 43 rubles, and FED 2 at 25 rubles, but less than the Zenit 3 at 80 rubles and the Kiev 4A at 115 rubles.

A second version of the Drug called the Drug-2 was also produced, but in extremely limited numbers. The Drug-2 added a selenium light meter to the front, moving the logo to the opposite side, and adding a meter readout to the top plate. The Drug-2 was available only in 1960 and a very small number were ever produced. It is not clear whether a metered version of the camera was considered while developing the Zorki 7 or whether this was a last minute addition that never caught on.

By 1963, all attempts to improve the Zorki family at KMZ had ended. At that time only the Zorki 4 and 6 were in production with the 4K coming in 1972 as the last in the series, staying in production until 1980.

KMZ would continue to manufacture optical equipment for decades to come. Models like the Start, Drug, Horizon, and Narciss would be some of the most innovative and highest quality of the entire Soviet Union. Unfortunately, due to political and logistical reasons far beyond the scope of this article, quality control would continue to suffer into the 1980s and 90s would fall into disarray after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Today, Soviet cameras are very popular among collectors. Although the more common models are easy to find, the more unusual models like the Drug are highly sought after. Most don’t work, but if you can find one in good working condition, expect to pay a premium. The good news, is that unlike lesser Soviet cameras which were always inexpensive, if you pay extra money for a working Drug, at the very least, you’re paying for a premium camera.

My Thoughts

There is something about cameras with less common methods for film transport that has always intrigued me. I’ve written many times about my fondness for wind up clockwork motor drive cameras, and I am very fond of the Kodak Ektra with it’s back door film advance. I’m less enamored with thumb wind cameras like the Konica III or the Zeiss-Ikon Tenax II, but still find them appealing. Of all cameras where you still have to do something with your hand to make the film advance, I think I like bottom “trigger” wind cameras the best. The Ricoh 519M, Canonflex R2000, and Canon VT Deluxe are all fantastic cameras to use.

When it came time to try out my next trigger wind camera, I remembered a previous trip to Vlad Kern’s house where I handled a KMZ Drug which was like a sleeker Zorki with a bottom trigger. I could have just borrowed one from Vlad, but never got around to it, and then I found one locally that was claimed to be in working condition for a reasonable price so I took a chance at it.

When I first handled it, I marveled at how clean the interface was. The Zorkis were based off the FED which is a copy of the Leica, and all Zorkis are evolutions of that first design, the Drug is like a total reboot, minus the lens mount. In fact, that the camera was originally going to be called the Zorki 7 but was later given another name was probably a wise move because once again, other than the lens mount, this camera doesn’t resemble a Zorki at all.

KMZ produced cameras were said to be of higher quality than those from most other Soviet camera factories, and based on the cosmetics and feel of the camera in my hand, the Drug does have an upscale feel to it. If you were to cover up the Cyrillic writing and put something German on here, you could easily be fooled into thinking this was an obscure German rangefinder. The satin chrome finish is as good as anything I’ve seen, the black vulcanite covering looks good and shows no signs of peeling or cracking, and all of the controls feel solid in operation and in their engraving.

Without a lens, the camera weighs 622 grams which is slightly lighter than a Nikon S at 643 grams but heavier than a Canon P at 564 grams, putting it comfortably between two highly regarded rangefinders. I have no idea of what Soviet photographers in 1959 might have thought about this camera upon it’s release, but I suspect that it made very good first impressions.

Up top, the camera looks nothing like a Zorki. The manually resetting exposure counter is in the upper left, behind a crescent shaped window. The counter is additive showing how many exposures have been made, and is reset by rotating the edge of the film counter which sticks out through a slot on the side of the camera.

To it’s right is the shutter speed dial. Showing it’s Soviet roots, the Drug is one of those cameras that you must advance the film before changing speeds. Not only will the shutter dial not show the correct speed before advancing the film, but attempting to change it will likely damage or at the very least, jam the shutter. If you jam it, it is possible to unjam it by making the correct movements of changing the speed back, but that’s not something I would feel comfortable recommending. To change the speeds, lift up and rotate the middle part until a black line points to whatever speed you like. Speeds 30 through 1000 are written in black and indicate the slow speed governor is not in use, but speeds 2 through 15 are in red which require some extra effort to set. Bulb is also written in red, but I do not know why. A line in between 2 and 30 indicates that you cannot turn the dial past that point. To go from 2 to 30 or vice versa, you must rotate the dial the complete opposite direction.

An accessory shoe is in the middle and a film reminder disc on the right. As was common with all Soviet cameras of the era, the film scale is in GOST, with numbers 11 through 350. This range compares to ASA 12 to 400. GOST 90 is the same as ASA 100. The Drug has no meter, so this dial doesn’t control anything on the camera. In the center of the film dial are settings for film type. A black circle represents black and white film, and a red sun and red light bulb indicate color film with the word цветная in the center, which means “color”.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical with the only exception being the door latch on the right side. Slide the lock down, near the bottom of the latch to release the film door. The Drug does not have any strap lugs, which means carrying it around either requires the original case, or something you can attach to the tripod socket. Unlike some other Soviet rangefinders in which strap lugs come and go on different variants of the same camera, I do not believe any Drug cameras ever had them.

Around back, we see a large patch of body covering over the entire door and above it are the round eyepiece for the viewfinder, an engraved KMZ logo, and two flash sync ports, one for flash bulbs and the other for electronic flash. To the left of the eyepiece is the camera’s serial number, which keeping with most Soviet cameras, the first two digits represent the year the camera was made. This particular example was produced in 1960, making it a somewhat earlier example.

The bottom of the camera is where the most exciting feature is, the film advance. To use it, you must first fold it out of it’s stored position. To do this, simply lift up on the tip of the lever using your finger nail and pull it out until it is perpendicular to the body. Once it gets here, it should lock into position. When it is time to fold it shut, a small release near the lever’s hinge must be pressed while gently folding it shut. For obvious reasons, the camera cannot be set down onto a flat surface with the lever out.

For anyone who has never used a camera with a bottom trigger film advance, it is done with your left hand while supporting the camera with your right. On the Drug I use my index and middle fingers on the trigger and let my ring finger and pinky hang off the bottom, with my left thumb pressed against the side of the camera. In the image to the right, I am holding the camera backwards so you can see where my hand would be in use. Normally my palm would be facing the rear of the camera, but otherwise my fingers are in the correct positions.

As much as the trigger film advance is the Drug’s most famous feature, sadly, it is not as smooth in operation as those I’ve used on Ricoh and Canon cameras. From what I understand, the lever drives the film advance and cocks the shutter via a long chain that needs proper lubrication, but has also been known to stretch, causing it not to move smoothly. As you might expect from a more than half century old Soviet camera, Drugs are often found in questionable operational condition, and only after a proper CLA will work as they were originally intended.

On opposite sides of the trigger is the 3/8″ tripod socket and film rewind knob. The tripod socket is larger than the 1/4″ ones used on Western cameras, so if you wanted to mount this to a modern tripod, you’d need an adapter. Activating the rewind knob is done by pushing in on it while also giving it a twist in the direction of the arrow. If you did it correct, the release will pop up about 5 to 6mm above the bottom plate. With it in this position, grip the knob with your fingers and the film can be rewound. To push it back in, you must press while also turning it in the opposite direction of the arrow.

Opening the left hinged door reveals the film compartment which is opposite of most cameras. Film transports from right to left into a non-removable metal take up spool. Attaching the film leader requires you to slide the tip under a metal clip so that a small tab sticks up into one of the film perforations and holding it still. After giving the camera a few advances, the film should wrap around itself securely.

The film gate looks normal and hides a cloth focal plane shutter which in this camera have held up remarkably well. The Drug’s curtains are made of rubberized silk, whcih is a higher quality material than what was used on most other Soviet, and even some German and Japanese cameras. Whether or not that is the reason the curtains on this camera are in such good condition, or whether this specific example just happened to be taken better care of than others, is not clear. Above and below the film gate and two rows of raw metal film rails. The rest of the film compartment is painted in what looks to be a thick black lacquer that has also held up well.

On the inside of the door is a polished metal pressure plate and a chrome roller to the side to help maintain film flatness as it transports over the geared shaft. The hinge side of the door and the film channels above and below the film compartment are very deep and require no light seals of any kind. This means that apart from cameras which show physical damage to the door, light leaks should not be a problem. A note about loading film is the rewind release I mentioned earlier, also doubles as the cassette fork, so you need to make sure it is in the fully lowered position before you can insert a new, or remove an exposed film cassette.

Most examples of the Drug came with a KMZ Jupiter 8 lens which is thought to have a slightly higher build quality than non KMZ Jupiter 8 lenses. A very small number came with the Jupiter 17, but this lens is uncommon. Regardless of which one you have, it works like most Soviet lenses. Focus is controlled by the ring closest to the body with distances engraved into the chrome in meters from 1 meter to Infinity. A depth of field scale is on a plate in front of the focus ring. Up front is the aperture control with engraved settings from f/2 to f/22. The aperture ring rotates smoothly without click stops.

The Drug uses the Leica Thread Mount like most other Zorki and FED rangefinders, which means lenses from those cameras can be swapped as can most LTM lenses made by most German and Japanese companies. I know that every time someone talks about Soviet lens compatibility, someone comes up with an example of a lens that doesn’t work, so I say the word “most” here, but if you’re like me, a majority of the most common LTM lenses you already have, will probably work fine. As this is a standard screw mount, changing lenses is done by simply rotating it counterclockwise to remove and clockwise to attach.

An interesting upgrade to the Drug that is not on any other Zorki or FED, is that the rangefinder coupling arm has a wheel on the tip, just like the original Leica and Japanese copies. Every other Soviet camera I’ve ever seen with a 39mm screw mount use a metal arm which is less secure and more prone to jamming. In the case of the Drug, KMZ went the extra mile and came pretty close to duplicating the original design which should improve rangefinder compatibility and make putting on and removing the lens easier.

Next to the lens mount, in easy reach of the photographer’s right hand is the cable threaded shutter release. The location of the shutter release allows for smooth presses of the button, minimizing body shake as the force required to press the shutter release is stabilized by the photographers face. With practice, this can allow the photographer one extra slower speed without blurred images.

Another cool feature of the shutter release is that if you hold it down while advancing the film, the shutter will immediately fire. This allows the camera to shoot a series of action shots one after the other in quick succession. The camera’s user manual suggests that with practice, you can achieve up to three exposures per second.

Below the shutter release is the mechanical self timer, which works independently of the main shutter release. With the self-timer activated, to begin the countdown, press the small button below the shutter release, and after about an 8 second delay, the shutter will fire. There is no way to cancel the self-timer after it has been wound, but as a workaround, you could shoot the rest of your roll as normal, never pressing the small button, and after finishing the roll, then release it.

Above and to the right of the lens, opposite of the shutter release is a small lever, that at first doesn’t appear to do anything. Before I ever loaded film into the camera, I was completely perplexed at what this lever does, but after a little bit of help from Google Translate, I discovered this is a rewind release lever. With the lever pointing down in the image to the right, film transports normal. If you rotate the lever counterclockwise and hold it as far as it will go, the film transport is deactivated so you can rewind the film. On my example, this lever feels loose and tends to flop around but the only time the film transport is deactivated is when you maintain pressure on it, so it’s looseness hasn’t been an issue for me.

The viewfinder is life size with no magnification, allowing the photographer to shoot with both eyes open for those who like to do that. It has contrasty frame lines for both 50mm and 85mm lenses. The square rangefinder patch is large and shows excellent contrast with the blue tinted patch around it. Although the frame lines offer no parallax correction, the viewfinder’s location directly above the lens eliminates any horizontal parallax with only the slightest amount of vertical error. Due to the 1:1 viewfinder ratio, the 50mm frame lines are at the extreme edge of what I can see while wearing prescription glasses, but are good enough to where I didn’t feel I would struggle with framing.

The viewfinder has a peculiar blue piece of glass that goes through the center which I assume is there to help improve contrast with the rangefinder patch behind it. In use, it is not distracting at all, but in the previous image of the viewfinder that I took with my smartphone, it threw off my camera. The image you see above is not representative of what it looks like in person, but I couldn’t get a good shot that shows what my eye sees, while still being able to see both sets of frame lines and the rangefinder patch. Just know that in person, the viewfinder and rangefinder is very good.

Overall, the KMZ Drug is an impressive camera. Although the Soviet Union did produce other ambitious cameras, the Drug seems to have that right balance of innovative and modern features, without stretching too far beyond what the people who made them, were capable of. Unlike other innovative cameras like the KMZ Start or Kiev 10/15 SLRs who used proprietary lenses, or the GOMZ Leningrad whose lens mount had a lip over it that interfered with many lenses that otherwise should be compatible with it, the KMZ Drug is compatible with nearly every M39 lens ever made. It has an excellent build quality and feels great in your hands with intuitive and easy to use controls. On paper, the KMZ Drug could be the best Soviet rangefinder ever made, but is it?

Repairs

Although this KMZ Drug is a bit stuff, it came to me in working condition. The shutter fired at all speeds, the viewfinder and rangefinder were both clear and accurate, and the lens was in excellent condition. If there’s one weakness of the camera that I would suspect is the first to have problems, it is with the film transport which relies on a fairly long metal chain. Although it has the appearance of brass, I would suspect that metal is far too soft, but I am unsure exactly what it is.

Nevertheless, if you were going to repair this camera, cleaning and lubing this chain is likely the first place you’d start, and while browsing the Soviet Cameras and Lenses Facebook page recently, I found the picture to the right of the Drug with it’s bottom plate removed. This isn’t my camera, but I thought it was interesting enough to share.

My Results

While I was pretty sure the Drug was in good enough shape for a test roll, I had some concerns with the film transport, so I decided to use the film I always use when I am unsure of the operation of the camera, Kodak TMax 100. Not only do I have a ton of it, it has a good amount of latitude which can absorb slight variances in shutter speed, and it’s a great looking film. I loaded up a bulk strip into one of my many reloadable cassettes, put it in the camera, and took it out shooting!

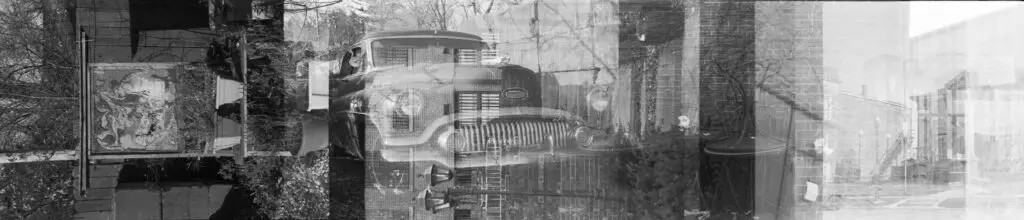

The images I got from the first roll had some good and some bad. The most notable “bad” was related to an issue with the film transport. I noticed that all of the images I took near the front of the roll overlapped. At first, nearly every image was badly overlapping, but the problem seemed to improve as I kept shooting. For the first 10-12 exposures, I ended up with a long montage of a bunch of images all laying on top of each other. Later images, like the one of the cemetery gates and the paint peeling off the wooden porch only show overlap near the edges. By the end of the roll, there was no more overlap.

In a weird sort of way, I kind of like the overlapped images as they work together, especially the old car, but of course, since there’s no way to predict this was happening, there would be no way to intentionally do this in the future.

The images I received from the KMZ Drug were very good. It really shouldn’t be a surprise though as the Jupiter-8 lens is well regarded as a very capable lens, especially when found in good condition, as it is a copy of the Zeiss Sonnar.

Sharpness was excellent across the frame when stopped down, but tended to soften a bit wide open. This is to be expected of any lens, but perhaps the Soviet interpretation of the original Carl Zeiss formula allowed for a bit more to creep in. I missed focus a bit on the lamp photo as I had the lens wide open and in the image of the Sophia’s Pancake Sign, the sky was very overcast, so I had it more open than the others. I don’t like to get into very technical details about lens sharpness or other things, but I would feel safe saying that anything f/5.6 and smaller, you’re not likely to be able to tell the difference between a Soviet Jupiter and a real Zeiss.

As I had some issues with the film transport, I decided not to do a second roll, so I never had a chance to shoot color, but I’ve shot color in other cameras using Jupiter lenses, and the bluish purple coating generally holds up well, delivering accurate colors while minimizing flare.

Since Jupiter lenses will likely deliver consistent results on a multitude of cameras, I have some worthwhile praise for the camera itself. I mentioned earlier that the build quality of the camera feels higher than that of a typical Soviet rangefinder, and that is something I still stand behind. The bottom film advance was comfortable and easy to use. Although I never attempted the rapid shooting sequence of holding down the shutter release while continuously advancing the camera, I could see how with a perfect lubricated and working camera, and a bit of practice, effective sequences of up to 2 exposures per second would be within reason.

The viewfinder was on par with that of the Zorki 4, which has previously been one of my favorite Soviet rangefinders. That the viewfinder is above the lens, eliminating vertical parallax is a nice touch too. The Drug uses a rangefinder coupling wheel instead of a lever like other Soviet cameras, and although I didn’t notice any improvement in rangefinder accuracy, I have to imagine that with heavy use, the wheel would hold up better.

Special care must be taken when changing shutter speeds as you must advance the film first. This serves two purposes, first, it allows the index mark to correctly show which speed you are selecting, but as an added benefit, it won’t break the camera!

As cool was it was, and for as much as I enjoyed using it, the biggest challenge of using the Drug was the film advance. Quite simply, no camera, Soviet or otherwise, was intended to be used for more than half a century without being serviced. The additional complexity of the chain driven advance was stiff, and would have definitely benefitted from service. Not only did the film advance feel stiff and required more effort than I predict the camera would have when it was new, I also believe that the overlapping film exposures were an direct result of the camera needing service.

Depending on where you live, finding someone willing (and able) to give a CLA to a camera like the KMZ Drug is difficult. For anyone willing to ship something to Slovakia, respected Soviet camera technician, Oleg Khalyavin lists the Drug as a camera he can service for 160 Euros. For those of you in the United States, the additional cost of two way international shipping may make it not economically viable, but at the very least, it is an option.

Whether you are lucky enough to have recently serviced KMZ Drug or have one that just works, these are wonderful cameras, and ones that are different enough from other Soviet rangefinders and have a combination of features not often seen, that they are worthy of addition to any collection. For the user of Soviet cameras, I feel comfortable saying that there isn’t anything better out there, with this combination of features, good build quality, and the capability of using any number of Soviet, Japanese, or German LTM lenses. Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.sovietcams.com/index7a19.html

https://fotoussr.ru/cameras/drug/ (in Russian)

http://ussrphoto.com/forum/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=715

http://photohistory.ru/index.php?pid=1207248178816328 (in Russian)

http://www.zenitcamera.com/mans/droug/droug.html (in Russian)

So “drug” equals “friend” …. Gives new meaning to that 1960s comment, “It’s ALL medicine”.

Love your reviews, Mike! Especially the effort you put in to communicate the context the cameras were built in (i.e., their history).

I must say I got surprised at the English title a little when I first read it, lol. I hope it’s OK to say that I’d use double-o, “droog” as that would be more phonetically similar to how people would say it (at least in the areas where I used to live).

I like the results you got with this camera. Indeed, film transport — not the lens, and not even the issues with aperture and shutter speed — is what causes my furstration with many old cameras. I recently tested another excellent Voigtländer Vitessa which gave me lovely renderings, as it does, except for three frames where it just double-exposed my shots for no reason other than I didn’t push the plunger in hard enough (probably).

Cheers,

how does one remove the top plate