This is a KMZ Horizont (Горизонт), produced in the former Soviet Union between the years 1967 to 1973 by Krasnogorsky Mekhanichesky Zavod (KMZ). This was the first model in a long line of successful swing lens panoramic cameras that were produced until well after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Considering the very high prices most dedicated panoramic cameras sold for, these Soviet made cameras are excellent alternatives that can still be had for a much lower price. Using a fixed focus 28mm f/2.8 lens, the Horizont captures 24mm x 58mm images through a 120 degree field of view. There is no shutter in the traditional sense as the motion of the swinging lens is what begins and ends the exposure, but variable speeds from 1/30 to 1/250 were possible. The earlier models are generally built well and can still be used today with only a small mount of servicing.

This is a KMZ Horizont (Горизонт), produced in the former Soviet Union between the years 1967 to 1973 by Krasnogorsky Mekhanichesky Zavod (KMZ). This was the first model in a long line of successful swing lens panoramic cameras that were produced until well after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Considering the very high prices most dedicated panoramic cameras sold for, these Soviet made cameras are excellent alternatives that can still be had for a much lower price. Using a fixed focus 28mm f/2.8 lens, the Horizont captures 24mm x 58mm images through a 120 degree field of view. There is no shutter in the traditional sense as the motion of the swinging lens is what begins and ends the exposure, but variable speeds from 1/30 to 1/250 were possible. The earlier models are generally built well and can still be used today with only a small mount of servicing.

Film Type: 135 (35mm) (24mm x 58mm panoramic images)

Lens: 28mm f/2.8 OF-28P coated 3-elements

Focus: Fixed, ~8 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Clip On, Scale Focus Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Swing Lens

Speeds: 1/30 – 1/250 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 922 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/horizont.pdf

How these ratings work |

The KMZ Horizont was created as a cost effective way to get into panoramic photography, a role that it still plays today. Compared to much more expensive models, at around $100, the Horizont is a great value if you can find one in working order. With the ability to change both shutter speeds and f/stops, the Horizont can handle a wide range of exposures and with it’s good triplet lens, makes excellent images. If you want to try your hand at 35mm panoramas, this is the camera for you. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.6 | ||||||

History

In the earliest days of photography, there weren’t a lot of rules. Early photographers also had to be camera makers and chemists. For a large number of early photographers, when you ran out of supplies for something, you had to make your own.

As the years went on, a few standard photography formats began to take hold, and one such format was the panoramic format. Since photography gives us the ability to capture moments, sometimes those moments consist of a large number of people or things. Sports teams, school graduations, and family reunions all could be captured on a single, large photograph using a panoramic camera.

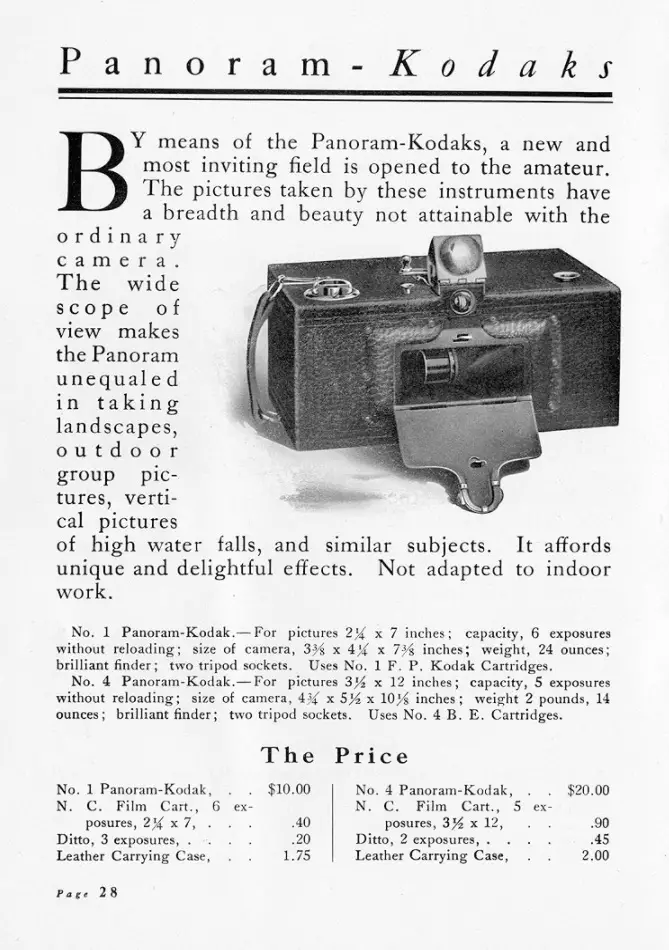

The most common, and easiest to make panoramic cameras around the turn of the 20th century were called “swing lens” cameras such as the Panoram-Kodaks. As the name implies, swing lens panoramic cameras have a lens that physically moves, or swings across the field of view to capture an image much wider than the lens could physically do otherwise.

Swing lens cameras usually use semi wide angle, small aperture lenses to maximize depth of field as there’s no easy way to focus a lens that moves. Not only that, these cameras don’t need a traditional shutter, as when the lens is stationary, it is oriented in a way that protects the film plane from light. Only when the lens begins to move does light pass through to the film, beginning the exposure.

The swing lens formula remained popular throughout the first half of the 20th century, but by the end of the World War II, new models had all but disappeared.

The next chapter for panoramic cameras began with a Russian weapons designed named Fedor Vasilyevich Tokarev who in 1948 created a prototype panoramic camera named the Fotoapparat Tokareva or FT for short.

The FT was built in the KMZ factory for the Soviet military and was not sold to the public. It was a simple box camera that used regular 35mm film in specially loaded cassettes which could take extremely wide panoramics across a 120 degree field of view, producing images that were 24mm x 110mm wide. An updated model called the FT-3 would be produced between 1952-53, but were also only produced for military or special use.

It is not clear exactly how many FT or FT-3 cameras were produced and for exactly what they were used for, but the design would stick around for another 10 years, when in 1958, KMZ would release an updated model called the FT-2 (ФТ-2) for civilian use. The FT-2 would retain the same basic brick like shape of the FT and FT-3, but would have different knobs and controls. Featuring a range of speeds from 1/100 to 1/400 and an Industar-50 lens, the FT-2 was one of the only options for swing lens photography at the time.

Interest would grow over the next couple of years, especially with the release of the 35mm Japanese Widelux. As one of the only options for Western photographers who would not have access to a low production Soviet camera originally developed by a weapon’s designer, the Widelux sold modestly well and paved the way for a whole series of cameras that would remain in production through the end of the century.

Perhaps sensing there was demand for an inexpensive panoramic camera that was easy to use and could be sold all over the world, using their knowledge of swing lens cameras, the KMZ factory would release an all new model called the Horizont (Горизонт). Despite using a similar lens design, the Horizont was entirely new. Featuring a much larger and easier to use body that uses regular 35mm cassettes instead of the proprietary ones of the FT-2, plus an optical viewfinder which was missing from the FT-2, the Horizont was a huge success.

Perhaps the biggest change with the Horizont over the FT-2 was in how shutter “speeds” were controlled. Neither the Horizont or the FT-2 had a shutter in the traditional sense. On the FT-2, the shutter would start out at it’s fastest speed, making an exposure as it swings across the film plane. If you selected a slower speed, one or two brakes were used to slow down the swinging motion, causing it to expose the film longer. Although this worked in concept, the use of brakes to make slower speeds would not remain consistent as the camera aged, or when it was used in colder environments.

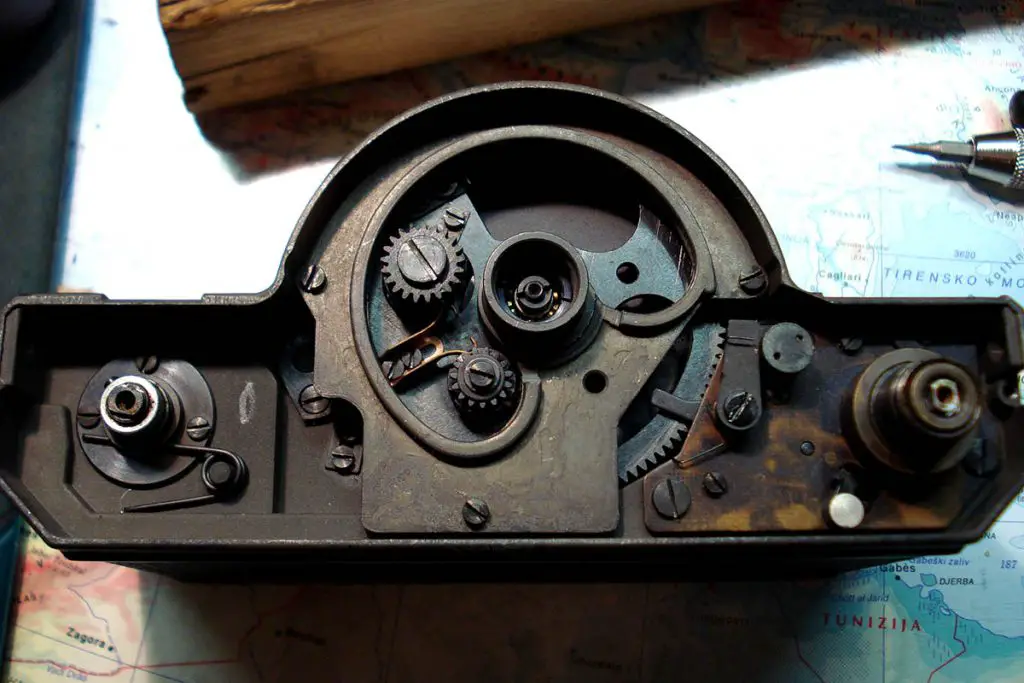

With the Horizont, exposure is controlled by a curved gate in the film compartment with a variable size slit that is connected to the shutter speed control on top of the camera.

With the speed set to 1/30, the slit is as wide as the entire gate. As you select faster speeds, the slit narrows down to a tiny sliver at the fastest speed which on early cameras is labeled 250, but on later models, is just a dot. When firing the shutter, the entire mechanism swings across the film plane at the same speed, regardless of which speed you’ve selected.

In the gallery below, I used my finger to stop the swinging motion of the shutter, the first at 1/30 on the left, and the second at 1/250 (indicated by a dot on this example) on the right.

The entire swinging motion of the shutter takes about half a second to complete, so even if you’ve selected the fastest speeds, you must take care to stabilize the camera so that it doesn’t move during the total duration of exposure.

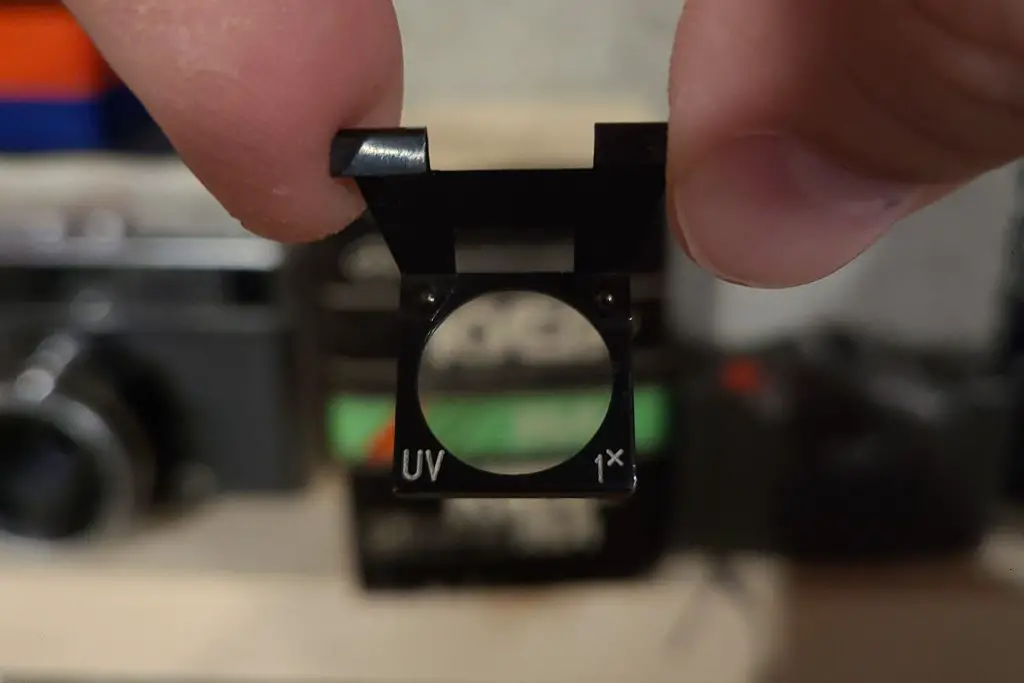

A feature of the Horizont that’s not found on many other swing lens cameras is that it supports the use of lens filters. Two specially designed clip on filters were available that attach to the lens, inside of the front opening. In the gallery below, I show the UV-1 filter, but a second yellow/green daylight filter also exists which I do not have called the ZhZ-2.

Installing the filter is as easy as inserting the left side first and pressing it flush up against the lens, allowing the two metal clips on the right to attach to the side of the opening. To remove the filter, you simply lift up on the two clips and the entire thing comes out.

The following article appeared in the February 1967 issue of Soviet Photo magazine, announcing the release of the Horizont. The article, simply called “New Panoramic Camera ‘Horizon'”. Using my best Google Translate skills, the article reads more like a press release, emphasizing specs and how the camera works. The top of the second page shows three sample images, including one vertical panorama.

Nearly 50,000 cameras were built between 1967 and 1973. Many were exported to other countries with name variants such as the Horizont Revue and Global-H. I could not find any information about what an export Horizont might have cost, nor any reliable metric for converting it’s Soviet price to anything that resembles current US dollars. Later versions of the camera produced between 1971 and 1973 came with a red logo instead of a black one, but otherwise are identical.

The Horizon name (minus the T) was reused a couple of times, the first being in 1989 with an updated model called the Horizon-202. Producing the same size 24mm x 58mm images with the same OF-28P lens, the Horizon-202 had an all new plastic body, with an integrated optical viewfinder, and a larger range of shutter speeds from 1/2 to 1/250. The Horizon-202 was produced for a couple of years, before being discontinued around 1991.

Finally, in 2006, a scaled down model called the Horizon-Kompakt was released in an entirely plastic body with only two speeds, and an MC 28mm f/8 lens. An oddity about the Horizon-Kompakt is that either the camera sold extremely poorly, or way more were ever produced than could ever be sold as a huge number of them can still be purchased as new old stock from various sellers online.

Today, the KMZ Horizont is quite a desirable camera. When it was first released, it was just as much of an economic entry into panoramic photography as they are today. Used prices for nice Horizonts are generally in the $200-$300 range which is a far cry from the several thousands of dollars cameras like the XPan and other dedicated panoramic cameras are.

In addition to it’s value, the images you can get from the Horizont are different from those from a cropped wide angle lens panoramic. Perspective is distorted in a way that gives images made from these cameras a unique look that many people are after today. Anyone can take a large image and crop it, but to get the look of a photograph from a swing lens camera, requires a swing lens camera.

Repairs

Although I did not attempt to repair either of the two Horizonts used in this review, while writing this article, I came across this excellent post by Ziga Cetrtic who goes over the entire process of servicing a Horizont, with many excellent photos. Perhaps at a later time, I will attempt to repair one myself. If I ever do, I’ll be sure to come back here with my thoughts.

My Thoughts

Panoramic cameras aren’t just regular cameras that take wider pictures. For anyone whose held a Hasselblad Xpan or a Fuji GX617 to their eye, the increased visual real estate completely transforms the shooting experience. How you think about what you want to photograph and frame your image is different. The view through a panoramic lens is a wholly different experience, that while can often have a high price tag, is something I recommend anyone reading this article to try out.

I’ve been fortunate to be able to try a number of panoramic options from swing lens, extreme wide angle, and even cropped panoramic cameras, but when my friend Anthony Rue from Gainesville, Florida asked if I wanted to try out a KMZ Horizont, I jumped at the opportunity.

The Horizont is a rather substantial camera. Weighing in at 922 grams, it has quite a bit of heft, especially considering the lens makes up very little of that weight. The body is wider than that of a Zenit, and if you include the clip on viewfinder, is also taller. With squared off edges and nothing in the way of a hand grip, this would be a difficult camera to hold during long shooting sessions without some kind of strap. I don’t know that a lot of people would use a swing lens panoramic camera during a long shooting session, but it’s something to keep in mind.

Up top, the Horizont barely resembles a camera with it’s overall shape and lack of normal looking controls. On the left is the clip on panoramic viewfinder, which is required to frame an image. You could use the camera without it, but you’d need to keep it balanced on a flat surface and have a solid understanding of the camera’s angle of view. On top of the viewfinder is a bubble level which is visible from within the viewfinder which is helpful in maintaining a level image.

The viewfinder is held in place by an accessory shoe on the front edge of the camera, and lifting it straight up reveals the rewind knob. In order to use it you must use your thumb to put downward pressure on it while giving it a clockwise twist. This will pop it up and allow you to rewind film at the end of the roll. When you are done, you push down on it again while giving it a counterclockwise twist to lock it into position.

In the center of the camera are the controls for the aperture and shutter speed. In the History section above, I explain how the Horizont shutter works as it’s not like a normal camera’s shutter. The aperture control works as you’d expect, opening and closing a diaphragm inside of the lens. Finally, there is a film reminder dial in the center.

On the far right is the cable threaded shutter release button, film advance knob, and exposure counter. You must manually reset the exposure counter after loading in a new roll of film, by lifting up the advance knob and turning it. The exposure counter is subtractive, which means you need to set it to the number of exposures remaining on the roll which is rather inconvenient because a normal 36 exposure roll gets 21, and a 24 exposure roll gets 13, both numbers that people likely aren’t used to thinking about.

The bottom of the camera has the same contour as the top, but with even less to see. There is the rewind release button, the 1/4″ tripod socket and the bottom of the door release latch. The location of the tripod socket is not ideal, considering the weight of the camera, and the frequent need to be mounted to a tripod.

Swing lens cameras like the Horizont more often require stabilization as the image can be negatively impacted by bumps and shakes. Although shutter speeds like 1/125 and 1/250 are usually fine hand held, these speeds are misleading as those are exposure speeds, meaning, that is the equivalent amount of light that will expose the film as the lens passes by the film. In reality, the lens still needs about one half to one full second of exposure to finish it’s motion, and any movement of the camera during the time in which the lens is moving, will cause the image to become distorted.

The camera’s left side gives an idea of the height of the camera with the viewfinder attached, and also gives another look at the film compartment door release. The Horizont has metal tripod lugs on both sides of the camera.

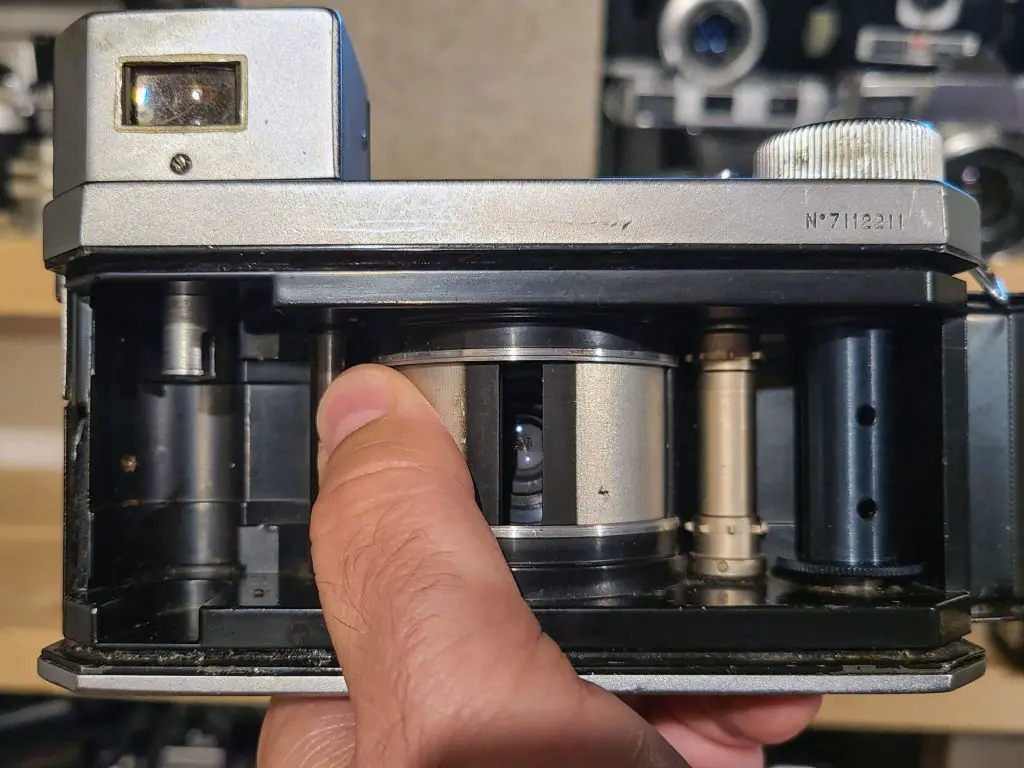

Opening the rear door reveals the film compartment, which like other swing lens cameras, looks very different.

Film transports from left to right onto a fixed, single slotted take up spool, but it takes a different path than most cameras. Thankfully, a diagram on the inside of the door explains how it’s done.

After leaving the supply cassette, the film must go behind a smooth post, around the curved film plane, then behind both the sprocketed shaft and take up spool, wrap around the far edge and onto the take up spool. Both the sprocketed and smooth posts maintain film pressure along the curved plane which takes the place of a pressure plate on the door.

Whenever I load film into most 35mm cameras, I attach the film leader to the take up spool first and then insert the cassette last because I can usually do it faster this way. With the Horizont you must insert the cassette first, and then thread the film throughout it’s path as there would be no way to fit the cassette under the two posts. Getting the leader around curved film plane and both posts is easy enough, but I really struggled getting it secured to the take up spool as the film is coming out behind the sprocketed post and there just isn’t a lot of room. Making matters more challenging is the take up spool has only one slot. Had the spool had multiple slots, it would have been much easier.

With the camera loaded with film, the door shut, and the exposure counter reset, you are ready to shoot film. The Horizont is focus free and uses the great depth of field offered by the 28mm OF-28P lens. According to the Soviet Photo article in the section above, the lens is set at a distance of 6 meters (~20 feet). Minimum focus distance changes depending on aperture, so you’ll want to use the smallest aperture possible if you want to get closer to your subject. Wide open at f/2.8 minimum focus is 16.5 feet, at f/8 it drops to 6 feet, and at f/16 drops again to 3 feet.

The viewfinder is a large and bright rectangle that estimates what will be captured by the swing lens. According to the Horizont manual, the angular field of view is 100 degrees horizontal by 44 degrees vertical.

A round spirit level is visible below the viewable image, but unfortunately, on this example, it had dried up. When this camera was new however, ensuring that the bubble was properly centered in the middle of the circle would guarantee level shots which is critical when capturing horizons on a panoramic camera, as getting it incorrect will result in a curved horizon.

A round spirit level should be visible below the viewable image, which when the bubble was properly centered in the middle of the circle would guarantee level shots. This is critical when capturing horizons on a panoramic camera, as getting it incorrect will result in a curved horizon.

Although the view through the viewfinder is large and bright, it has a pronounced pincushion shape on the top and bottom which you will not see in the final image, making it somewhat difficult to frame exactly what will be captured on film. This isn’t a huge issue though, as it is not common for panoramas to have tight framing. By far, the two most important things to get right in the viewfinder is keeping the camera level and centering your exposure.

Perhaps the greatest strength to the Horizont series is the same one that it had when it was new, it offered true panoramic images for far less than other options. Most cameras of this type are very expensive, but you can pick up a Horizont, usually in good working condition for between $100 and $200, which is a far cry from other options out there. I was really excited to get a chance to shoot one of these, so keep reading to see my results.

My Results

When I first received the Horizont, I was really excited to go out and shoot it. After all, I thoroughly enjoyed my time with two other panoramic cameras I’ve reviewed, the Kodak No. 1 Panoram, and the Hasselblad X-Pan. The problem with panoramic cameras however is a sense of obligation that I get of being able to find shots worthy of a panoramic picture. Sure, I could just point the Horizont at a fire hydrant on my block and take a photo of it, but somehow that doesn’t seem worthy. I ended up letting it get to me and I found myself often talking myself out of loading it.

When I finally just got over it, and took it out, the first roll was some bulk Kodak Vision3 500T that I have a large supply of, and for the second, a fresh roll of Kodak ProImage 100 that I would take with me on a family trip to the north central part of the United States.

When he sent me the Horizont, Anthony warned me not to use the fast speeds as they showed banding. For the two rolls of film, I kept the speed at 1/30 for most of them, and only used 1/60 in direct sunlight.

As it would seem, the banding issue was visible on every shot I took, even those at 1/60 suggesting that whatever is causing it, is getting worse on this example. Although disappointing to see, it didn’t ruin my experience with the camera and I feel as thought I can still draw several conclusions about the camera.

In the process of writing this review, I was contacted by Vladislav Kern from USSRPhoto and asked me if I was interested in a red label Horizont that was coming to him in a shipment from Russia. Not wanting to pass up a good deal, I took him up on his offer and picked up a second Horizont that appeared to be in good working condition. Knowing that the first one I shot had banding issues across all frames, I quickly loaded in a test roll of Kodak TMax 100 to see how it would perform.

Light leaks and a vertical banding issue, likely caused by the swinging motion of the lens having a slight stutter, the second Horizont also had issues.

Despite the less than ideal results from the two cameras, you can still see the 28mm f/2.8 OF-28P triplet is more than up to the task of delivering sharp and detailed images. The color coating rendered colors correctly with just the slightest hint of exaggeration on the expired Kodak Vision3 500T. The ProImage 100 and Tmax 100 images from the second camera all look as they should on a non-panoramic camera with excellent contrast and accurate colors.

Unlike panoramic cameras with a non moving wide angle lens where sharpness drop off and vignetting can occur near the edges, the Horizont’s lens physically moves throughout the frame, extending it’s sweet spot, making edge softness less of an issue than on fixed lens panoramic cameras.

KMZ’s use of a simple triplet lens was a good choice as the simpler lens not only keeps the cost low, but it’s small size means it could fit into a tighter spot. It’s 28mm focal length also provides excellent depth of field, allowing it to be used as a focus free camera. Had the Horizont came with a more complex 5 or 6 element lens, you’d have a more expensive and physically larger camera that wouldn’t produce images with a noticeably better image quality.

Happy Accident: I included an image in the gallery above showing me and a girl in a pink shirt. This was an accidental exposure where I was trying to explain to her how a swing lens camera worked. The camera is at arms length and while I am a bit blurry, the girl, who is standing right next to me is reasonably in focus, showing how close you can get to your subject and still have an in focus image.

The banding issues visible in all of the images above are common with the Horizont and were the number of complaint I read about the camera in other reviews. While I’ve seen plenty of images without them, this is definitely something you’ll want to confirm isn’t an issue if you plan on buying one of these cameras and using it.

By far, the biggest challenge with using the Horizont is both finding scenes that work well as a panorama and framing it. Landscapes are the easiest to do as it’s not difficult to frame those, but getting creative with closeups can be a challenge. In fact, it was my inability to find things worthy enough of a panorama that caused me to delay shooting the camera. I think that with repeated use, it can become more natural, but for someone like me who doesn’t use them as often, it can be hard to put these cameras to good use.

Overall, the Horizont is a heck of a fun camera to shoot! Despite having trouble with both cameras I used, I still came away with a positive impression of it. Like any half-century old mechanical device, these things need servicing. Perhaps the nature of a swing lens camera requires more precise maintenance than a rangefinder or SLR, but there’s still enough good here to see that when found in good working order, these are great cameras. I’ll keep looking for a better example and hopefully come back here someday to update this review with sample from an entirely good roll!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Horizont

http://www.zenitcamera.com/archive/horizon/index.html (in Russian)

https://apenasimagens.com/en/horizont-kmz-2/

https://walkclickmake.com/2017/03/02/camera-tales-the-horizont/

https://erikwitsoe.blog/2019/04/05/horizont-panorama/

http://lenscraze.blogspot.com/2014/01/kmz-horizont-camera.html

http://zigacetrtic.blogspot.com/2013/07/kmz-horizont-panoramic-camera-servicing.html

https://eastrise.wordpress.com/2014/08/25/видеть-шире-фотоаппарат-горизонт-то/ (in Russian)

Хорошая статья, товарищ! Нам нравится. Продолжайте…

Thanks! I am glad you enjoyed it!

Great job- as usual. I found it takes a lot of practice to get the best out of rotating lens cameras- whereas the X-Pan is quite straightforward. You CAN buy a lot of film to learn with for the difference in price these days

Very nice article as usual, Mike…

I’ve owned one of these for a number of years, along with an FT-2 (which generally suffer from different issues), and have had them apart to clean and adjust. The vertical banding you’re getting on the second Horizont appears to be a combination of two issues. You certainly have uneven lens speed travel, but you also have at least one light seal that has deteriorated, as the left side of all the images have a wider, stronger band in the same area. You get this particular wider band while the camera is at rest waiting to be exposed. With the back open, you should be able to shine a light through the front of the rotating part of the lens turret itself – where it meets the camera body – and see light through the back to confirm. To fix the vertical banding caused by inconsistent travel speed, it just needs to be cleaned and lubed, and should then give most excellent results. Really, these are wonderful cameras in working order.

The horizontal banding you’re getting with the first camera is something I’ve never seen before in mine, but I suspect that it too is due to the same light seals, just manifesting itself in a different way. These have a light seal that’s made of fine hair-like fibers mounted on a foam backing. If you’ve ever seen an old Voigtlander 9×12 camera sheet film/glass plate holder, it’s a similar hair fiber “tape” that’s used for the light trap. The hairs tend to crush and flatten out, all lie one way, or just separate. I’ve seen them even appear moth eaten with paths eaten through them. Check with a flashlight in the same manner, and I think you’ll likely find the issue.

Hope this might help.