This is a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye Flash, an all plastic box camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York between the years 1950 and 1961. It was an update to a non-flash version that was released in 1949. All Brownie Hawkeyes take 6cm x 6cm images on 620 format roll film and have a fixed focus single element lens, single speed shutter, and a single aperture making them very easy to use. With an original price of only $4 for the camera, the Brownie Hawkeye was extremely popular throughout the entire 1950s, making it one of the more popular cameras in the United States at that time.

This is a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye Flash, an all plastic box camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York between the years 1950 and 1961. It was an update to a non-flash version that was released in 1949. All Brownie Hawkeyes take 6cm x 6cm images on 620 format roll film and have a fixed focus single element lens, single speed shutter, and a single aperture making them very easy to use. With an original price of only $4 for the camera, the Brownie Hawkeye was extremely popular throughout the entire 1950s, making it one of the more popular cameras in the United States at that time.

Film Type: 620 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 81mm f/15 uncoated Single Element Meniscus

Focus: Fixed, 5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Rotary

Speeds: Bulb, 1/40 Single Speed

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Kodalite Midget Flash Holder

Weight: 460 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_brownie_hawkeye.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kodak Brownie Hawkeye was one of the most popular and iconic cameras of the 20th century. Featuring a classic mid-century design, incredibly easy operation and a low price, the camera was a favorite for family snapshooters and children alike. Despite it’s rudimentary feature set, the camera delivers better than expected images in a wide range of shooting situations. Whether you like cameras display pieces to admire, or taking them out for their intended purpose, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye is an easy camera to recommend. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, classic design, and ease of use | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.1 | ||||||

History

I’ve written plenty of reviews for Kodak cameras throughout the 20th century from the highly ambitions and extremely expensive Kodak Ektra to the incredibly tiny and simple Kodak Baby Brownie Special, and one truth that can be seen time and time again throughout their history was that the Eastman Kodak Corporation was a film first company. Yes, Kodak made cameras, quite a few actually, and some were quite good, but no matter how advanced a particular model was, Kodak’s priority was to sell film. Although Kodak film could be used in other company’s cameras, by getting even more cameras at cheaper prices into consumers hands, the more people would likely stick with Kodak film.

I’ve written plenty of reviews for Kodak cameras throughout the 20th century from the highly ambitions and extremely expensive Kodak Ektra to the incredibly tiny and simple Kodak Baby Brownie Special, and one truth that can be seen time and time again throughout their history was that the Eastman Kodak Corporation was a film first company. Yes, Kodak made cameras, quite a few actually, and some were quite good, but no matter how advanced a particular model was, Kodak’s priority was to sell film. Although Kodak film could be used in other company’s cameras, by getting even more cameras at cheaper prices into consumers hands, the more people would likely stick with Kodak film.

This was a strategy that Kodak’s biggest competitors, Fuji and ANSGO/AGFA/GAF employed as well as both companies also produced their own lineups of models concurrently with their film stocks, Kodak was just more successful at it.

The mid 20th century saw a huge demand for snapshot photography by novices who had no interest in learning the complexities of exposure or composition and just wanted a camera they could point at something and record an image of it.

Kodak was happy to oblige these customers by releasing a dizzying array of new models in variety of shapes, sizes and colors. Whether you wanted to shoot 35mm Kodachrome slides, larger 6×6 contact prints on 620 roll film, or if you wanted a twin lens reflex or eye level point and shoot, Kodak had something for you.

According to kodaklist.com, in the ten year period from 1950 to 1960, Kodak released a total of 60 different unique models, but the number is higher if you consider variants or different colors of the same camera, plus a few more that were introduced before 1950 and were still being sold. With such a huge number of cameras on dealer’s shelves, it’s likely some models sold better than others.

Of the cameras that sold well, one of the best was the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye and Hawkeye Flash which together, were produced between the years 1949 to 1961. The camera was designed by Arthur Crapsey Jr who designed a great number of cameras for Kodak including the Kodaks Pony, Bantam Rangefinder, Stereo, Signets 35 through 80, and Automatic/Motormatic 35, plus many others. The camera was made mostly from a newly developed type of thermoplastic called Tenite which was both lighter in weight and less brittle than Bakelite which had been the plastic of choice for early 20th century camera makers. The earliest examples have metal film advance knobs, but these were quickly replaced with plastic ones.

I have no idea of how many Brownie Hawkeyes were ever made, but in the time I’ve been collecting cameras, I’ve gone to hundreds of garage and estate sales, thrift shops, antique stores, and other types of second hand shops, and I see more Brownie Hawkeyes than any single other model by any company. If the Argus C3 was the most popular American 35mm camera, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye has to be the most popular American camera of any format.

The secret to the Brownie Hawkeye’s success was it’s 1-2-3 punch of a low cost, easy operation, and quality images.

Regarding it’s cost, the original non-Flash Brownie Hawkeye sold in 1949 for $5.50. In 1950 when the model was upgraded with flash capability, the price rose to $7.20, or for $10.59 with the flash attachment. In later years, the camera and flash came together in a gift box with a roll of film and a couple of bulbs for $13.95. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to about $61, $74, $108, and $130 respectively today, quite a meager price for a family snapshot camera.

As for it’s operation, it doesn’t get any more simpler than this, with a focus free lens that gives good sharpness from 5 feet to infinity, and a single shutter speed and aperture that matched the most common color and black and white films of the day, little to no thought needed to be given to the camera’s operation other than point and shoot.

Lastly, in regards to it’s image quality, Kodak had a knack for extracting an impressive amount of detail out of simple cameras and lenses as I’ve shot quite a number of simple mid century plastic Brownies and other simple cameras that deliver images that look much more impressive than the camera or lens’s specs might suggest.

In more recent years, the Brownie Hawkeye has developed somewhat of a cult following for it’s classic Mid Century Modern design. These cameras are often used as ornamental decorations on shelves, but to the horror of some collectors, are popular models to be modified and turned into lamps, clocks, and even pencil holders. Another type of modification is to take them apart and paint them all the colors of the rainbow. Pastel colors common in the mid 20th century are favorites such as this gorgeous seafoam green and cream colored example to the left.

Due to the simple nature of the camera, photography magazines like Pop and Modern Photo rarely mentioned it, so I was unable to find any kind of contemporary review or technical write up about the camera as the typical customer of those magazines would not have been the target customer for this camera.

Advertisements from the era claimed the Brownie Hawkeye to be the “World’s Most Popular Snapshooter” which is likely just marketing fluff, but the camera did sell well both in the United States and other countries. The camera was sold in the US and most of the world as the Brownie Hawkeye, but versions exist as the Brownie Fiesta, and models made in France by Kodak Pathé SA as the Brownie Flash Camera.

With a production run of over 10 years, the Brownie Hawkeye and all of it’s variants was extremely successful. I’ve not found any estimate of how many were built, but compared to other popular mid-century Kodak cameras, a total number of over a million does not seem unreasonable. With over 500 current eBay auctions for Brownie Hawkeyes, and how often I’ve seen them at garage sales and antique stores, the number could be even higher than that.

Today, the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye is very popular for the reasons I’ve already mentioned above. They’re so common, they can still be found for very little, in fact, I picked up this one for $1 and while that might not be reasonable for people not in the United States, they are still very plentiful.

My Thoughts

I’ve only been to London once, and never to Germany or any former Soviet countries, but in my mind’s eye, I picture whole buildings built entirely out of Ensign Ful-Vues, Prakticas, and Zorkis. There are probably traffic laws requiring motorists to yield the right away to anyone carrying a Purma Special, Edixa-Reflex, or a Zenit-E. For those of you reading this in those countries, you probably feel the same way about America where we build houses out of Argus C3s and Kodak Brownies.

Of course the reality is, we only build small houses out of Kodak boxes, but of all the Kodak box cameras, the one I see the most often are the Brownie Hawkeyes. I actively would avoid them at garage sales and it wasn’t until I spotted this one for $1 that I finally succumbed to fate and bought it, figuring that for such an iconic camera, I should probably give one a shot.

Operating the Brownie Hawkeye is as easy as it gets. With a vinyl carrying handle on the top of the camera, the only other things you see are the opening to the brilliant waist level viewfinder, and shutter release button on the left. The shutter is a self-cocking design, so a single press of the shutter release both tensions and releases the shutter in one single motion. For fans of symmetry such as myself, opposite of the shutter release is a very similar looking piece of plastic that at first doesn’t look like it does anything, but is actually a shutter control feature that when lifted, allows for long exposures to be made. Lift it up, and the shutter is in Bulb mode, and when pressed down, it’s in Instant mode.

As is the case of most waist level brilliant finders like this one, the camera cannot be held too close to the eye while looking through the viewfinder or else you won’t see the entire image. You must hold the camera at least six or so inches away from your face to see a properly framed image.

Without any control over focus or exposure, the only part of the camera you need to know about is the film advance knob on the camera’s right side. The Brownie Hawkeye does not have sort of double exposure prevention or an automatic film stop, so you must remember to advance the film after each shot, and be sure not to wind the film past the next exposure number, which can be seen through a red window on the camera’s back.

Loading film into the camera requires removing removing the entire back and sides of the camera. A small metal arm sticking out of the latch for the vinyl handle on the top of the camera acts as the film compartment lock. Move this arm forward and you can separate the camera into two halves.

With the camera opened, the entire film compartment comes out in one piece. In the image to the right, instructions for loading the camera are printed on the inside of the film compartment. The take up spool is on top, and a fresh supply of film goes on the bottom. The Brownie Hawkeye, like most mid century Kodak roll film cameras uses 620 film, which uses the same size film as 120, but on smaller spools. A label on the bottom side of the film compartment warns not to use 120 film spools, which will not fit.

Although Kodak has not produced fresh 620 film since the mid 1990s, currently available 120 film can be easily rolled onto 620 spools in a dark room or film changing bag. Alternatively, there are modifications you can make to the camera to accept 120 film without having to respool it, but I prefer respooling as it is fast and easy to do and does not alter the camera. Mike Raso from the Film Photography Project has a video that shows how this can be done.

A Word About Film Speeds: In the Brownie Hawkeye’s manual, it recommends Kodak Verichrome Pan for general purpose photography or Kodacolor film, both of which had ASA film speed ratings of between 25 to 80. You can use faster films today, but you’ll need to take care to protect the red window on the back of the camera as the faster the film, the more sensitive to light coming through the red window it will be.

Loading films faster than 200 into the Brownie Hawkeye is not recommended both because it will be beyond the range of the single shutter speed and aperture the camera is capable of, but also that the chances of light leaks through the red window is greatly increased.

The camera’s left side has both ports for the optional Kodalite Midget flash holder and the side profile for the shutter control that switches between Instant and Bulb mode. Although looking like a mirror image of the shutter release, in it’s normal resting position, the shutter is in Instant mode which gives a speed of approximately 1/40 second, but if you lift it up to a raised position, the shutter is in Bulb mode for long exposures. I will be completely honest that I didn’t realize the camera had this feature until I read the manual, so I wonder how many people went years owning a Brownie Hawkeye without realizing this feature was there too!

It is clear the Kodak Brownie Hawkeye is a simple camera. Millions of simple cameras were made by companies all over the world in all shapes, sizes, and using a wide variety of film formats. This model seems to be more popular than others, but why is that? Does it’s use invoke some kind of transcendent experience in it’s use, or is it just good looking? I guess there is only one way to find out!

Repairs

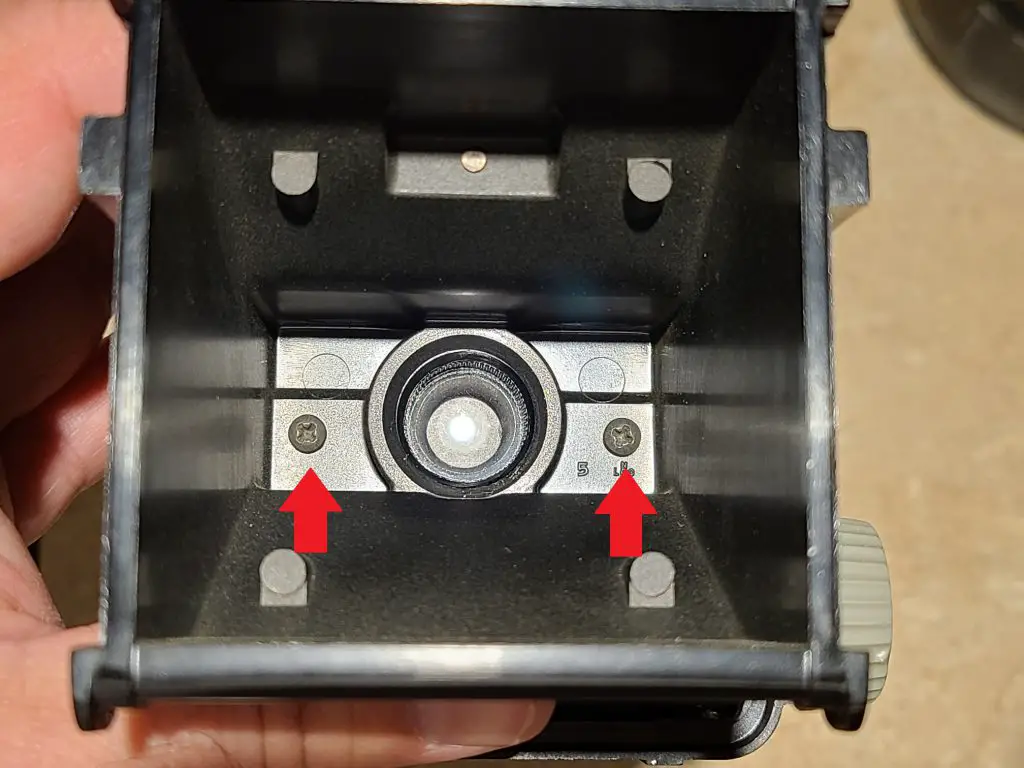

This particular Brownie Hawkeye came to me in working condition but the lens was extremely hazy which required me to open it up and clean it. The Brownie Hawkeye is one of the simplest cameras to open, as it only requires removal of four screws, two inside the film compartment and two on the front plate to clean everything you need to clean.

If you need to do this yourself, just get a small screwdriver and remove the back of the camera so that you can see inside of the film gate. Remove the two screws indicated by the red arrows, and the plastic film gate and film holder comes out. This piece holds the lens in place with tension. On some cameras, the lens may still be attached to the back of the gate, but on mine, it was laying there loose. Whichever is the case for you, just pick up the lens and clean it. There is also a crush washer behind it that will likely fall out too that you don’t want to lose.

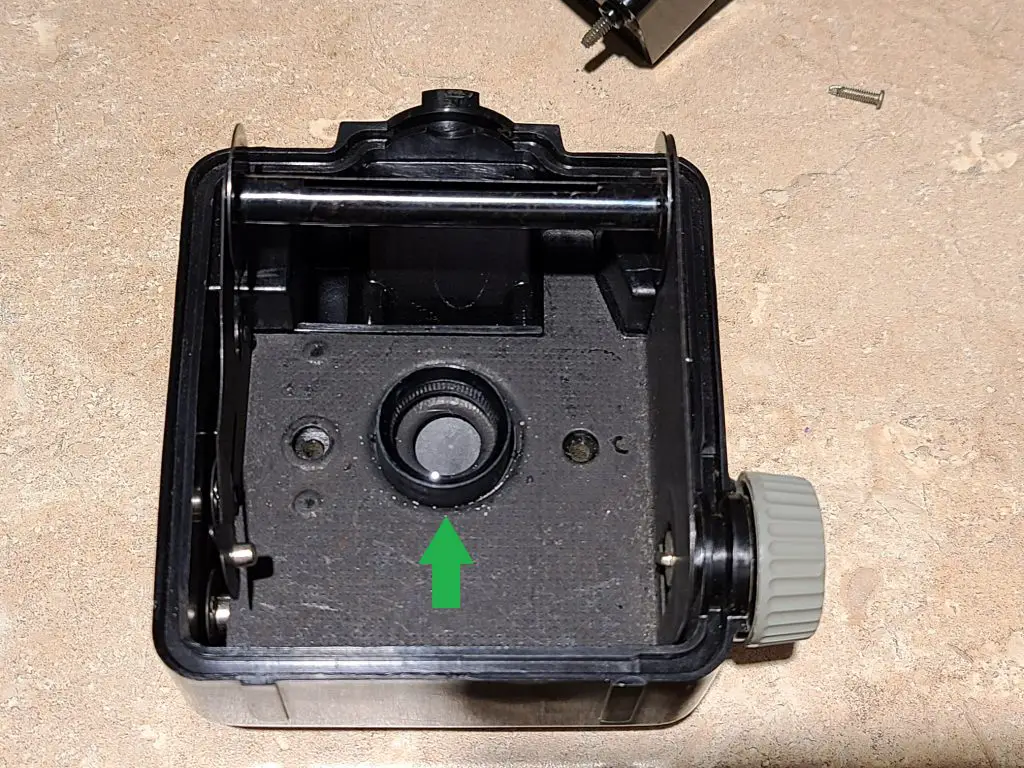

Even after cleaning the lens, there is a glass window on the front of the camera which may be dirty and needs cleaning as well. On mine, this piece of glass was dirtier than the actual lens and was the cause of most of the haze.

To get to this glass window, you must lift up the curved metal plate on the front of the camera. There are two screws on the front plate and two more next to the viewfinder. I recommend only removing the front two, as removing all four will cause the viewfinder to come loose and since you don’t need to actually get to the viewfinder, I think its better to just remove the two screws indicated by the blue arrows below. With those screws out, gently lift up on the metal plate and pull out the plastic lens baffle and the square piece of glass behind it. Wipe down the glass with a soft cloth and some glass cleaner and when it’s clean, put it back in.

Reassembly of the camera is the opposite of how you took everything apart. This whole process shouldn’t take you more than 5 minutes to remove and clean both the lens and the glass window.

Although mine had a perfectly working shutter, if you notice the shutter on yours is sluggish, this is also a good opportunity to clean it.

To get to the shutter, in the step above after you remove the lens to clean it, you can also pull out the metal plate behind it. There is nothing holding this piece in place, it just lifts out and reveals the entire shutter mechanism behind it.

I won’t go any further as to how the shutter works, but I would imagine that any sluggishness can be resolved with a liberal dousing of naphtha oil or lighter fluid.

My Results

My first roll of film through the Brownie Hawkeye was an expired 620 roll of Kodak Gold 200 that was of unknown age. I figured with a single shutter speed in the neighborhood of ~1/40 of a second and a film of unknown age, the exposure should be correct, so I took it out shooting.

When I saw the results of that image, I noticed that I missed one critical step in my “camera vetting process” which was to check the condition of the lens. Apparently, I was so quick to shoot this camera, I never bothered to look through the lens to see that it was coated in a thick haze. Whoops.

Looking at these images, they are extremely soft, almost as if someone was shooting through a set of sheer nylons. I took the camera back home, opened it up and wiped clean the lens, getting rid of a half century’s worth of dust and whatever else makes haze and tried a second roll.

For the second roll, I wanted to use a roll of real 620 film instead of re-rolling fresh 120 onto a 620 spool, so this time tried some 1980s Kodacolor II. I had pretty good luck with this film in reviews for the Kodak Medalist and Kodak Duo Six-20 and thought I’d give it a go on my recently cleaned Brownie Hawkeye.

Having a chance to look at the second roll of images, I saw what I had expected to see, which was a roll of 12 good images exactly as Kodak’s advertisements for the camera had promised.

Eastman Kodak had a knack for making cheap cameras that still delivered the goods in terms of image quality. Considering these cameras were used as snapshot cameras by people with little to know knowledge of photography, getting a good sized 6cm x 6cm color or black and white print was good enough for them.

For photographers today who like images that deliver a “vintage” look, it doesn’t get much better than this. The simple 81mm meniscus lens manages good sharpness corner to corner. Vignetting and edge softness are visible, but not at all distracting delivering images that look exactly as you might imagine those shot with an almost 70 year old box camera would.

Although not my initial intent, my use of 30+ year expired Kodacolor II delivered some otherworldly colors that gave the orange and yellow colors of the autumn leaves a visual pop that only a liberal use of Vibrancy and Saturation sliders in Photoshop would be able to recreate. I assure you though, there’s no post processing magic at work here, these colors are exactly what I got from the film.

Kodacolor II film originally was rated at ASA 100, and my use in brightly lit outdoor scenes and a 1/40 shutter speed likely gave it more light than fresh film would have liked, but it worked well here. If I were to load up some fresh color film into the camera, I wouldn’t want to go any faster than that and certainly stay away from films with low latitude.

Although I did not shoot any black and white film, I feel confident that any film with a speed from ASA 25 to probably 200 would have worked fine. The Kodak Brownie Hawkeye is a simple camera that is a lot of fun to use, and I can definitely see myself giving it another go again, and when I do, I’ll be sure to come back and update this gallery with more shots, but if you can’t wait, there are many examples of other people’s results to be found online.

The Kodak Brownie Hawkeye was an inexpensive camera that was designed to be easy to use, and that is still as true today as it was more than half a century ago when they were built. The simplicity of the camera is what allows most of them to still be in good working condition today. Other than a cleaning, you can step into the shoes of the men and women who used these cameras way back when and get the same results.

Don’t let the fact that these cameras use 620 film dissuade you from wanting to try one of these out. If you are in the United States, these cameras should be very easy to find at garage sales, thrift shops, and at antique stores. Heck, you might even have a relative or neighbor with one in their closest, and if you do, they are absolutely worth putting a roll or two of film through them. And if you’re just not into shooting old cameras, they display very well too.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Brownie_Hawkeye

https://www.brownie-camera.com/27.shtml

https://kosmofoto.com/2020/03/route-66-on-a-kodak-brownie-hawkeye/

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2016/02/24/ccr-review-32-kodak-brownie-hawkeye-flash/

https://alysvintagecameraalley.com/2020/10/12/kodak-brownie-hawkeye-camera-flash-model/

http://kurtmunger.com/kodak_brownie_hawkeyeid149.html

http://mattsclassiccameras.com/tlr-box/kodak-brownie-hawkeye-flash-model/

https://www.shutterbug.com/content/why-i-still-shoot-vintage-kodak-brownie-hawkeye-film-camera

I can’t believe you hadn’t reviewed one of these yet! Nice to know I’m not the only one who shoots a camera before checking whether the lens is clean.

I try to balance my reviews with equal numbers of obscure cameras and common ones. Although there’s a ton of info on these out there (including your excellent review), I felt I should throw my hat into the ring and also show how to clean the lens. And yeah, sometimes I cut corners when testing a camera, and that has a tendency to bite me in the butt sometimes!

I have a nice little one I bought for display. I think I’ll clean it up and take it for a spin.

It’s definitely worth it. I think you’ll find that it’s quite enjoyable to use. Just make sure the lens and that glass window are clean! 🙂

Hi Mike,

This is a very enjoyable read. I have a Brownie Hawkeye in new condition that I have been tempted to investigate getting 620 film for it. After seeing your examples of photos made with the Brownie Hawkeye, I will definitely feed some film to mine. Sure, it is not a Rolleiflex, but heck, there is nothing wrong with the photos you made. They are really enjoyable to view.

Jeff

In that seafoam colouring it looks a very pretty camera and one reminiscent of summer holidays at the beach with transistor radios! If you’re going to make a very, very basic camera, at least make it look nice, and the Kodak designers certainly did.

Image quality surprised me from a single meniscus f15 lens. Much better than Holga and Diana images Ive seem posted on-line.

Nice post. Have you tried the flipped lens mod? A bit out there and makes it a one-trick pony but fun to use, particularly if you pair that with one of the lomography films. May be an extreme look for some, but lends itself to experimentation. Cheers

I am familiar with this mod and have seen the results other people have posted online, and its just not for me. I get that a lot of people like it, and its a pretty easy thing to do.

An easy “flip” mod is to reverse the front element of a Helios model 44, 58mm f2 lens. These typically have the M42 mount so you can play bokeh games with your choice of camera body.