This is a Kodak Retina Automatic III 35mm rangefinder camera made by Kodak AG of Germany between the years of 1960 and 1963. It was the top of the Retina Automatic series with a 6-element Retina-Xenar f/2.8 lens and coupled rangefinder. The signature feature of the Retina Automatic series was that it was capable of shutter priority auto exposure via a selenium cell light meter. Despite this advanced feature (for the time), it was still a fully mechanical camera that had a range of aperture sizes and shutter speeds available to the user.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: Schneider-Kreuznach Retina-Xenar 45mm f/2.8 coated 6-elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder with 45mm Projected Framelines

Shutter: Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Gossen Selenium Cell Auto Exposure

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and PC Flash Sync

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_retina_a_iii.pdf

History

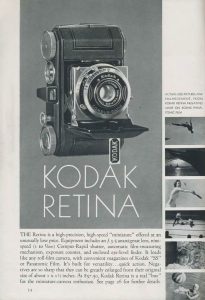

The Eastman Kodak company released the first Retina camera in 1934 simultaneously with the debut of their new 35mm film format, known officially as format 135 film. The Kodak Retina was a scale focus folding camera designed by Dr. August Nagel, and built by Kodak AG, which was based out of Stuttgart, Germany. Originally founded as Nagel Kamera-Werk, Kodak would purchase Nagel’s company and retain him as a chief designer of all of Kodak AG’s products.

All Kodak Retinas, along with other Nagel designed cameras like the Vollenda, Recomar, and Duo Six-20 models were high quality cameras built to high German standards, with state of the art lenses and shutters. They would remain a high-mark in Kodak’s portfolio both before and after World War II.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, models like the Kodak Retina II and III were some of the most advanced 35mm cameras made by any company in the world. In the April 1955 issue of Popular Photography, a Retina IIIc with the standard f/2 50mm lens was said to sell for $185. When adjusted for inflation, that’s like $1681 in 2017. The later Retinas had an interchangeable lens mount, and when equipped with some other lenses and accessories, the price of a full Retina system could exceed well over several hundred dollars placing it into the territory of the most expensive models of the time.

Despite the high praise of the entire Retina series, by the mid 1950s its popularity started to wane in favor of non-folding rangefinders, and eventually SLR cameras. In an effort to extend the relevance of the Retina line, Kodak AG would eventually discontinue the folding Retinas and replace them with solid bodied versions. While the non-folding versions had the disadvantage of making the cameras less compact, they did eliminate the moving parts of the hinged front door and bellows system, allowing the cameras to be built for less.

Although a cheaper line of Retinas, known as the Retinette, had been available as early as 1954, the first official ‘Retina’ model was not released until 1958. This first non-folding Retina was called the Retina IIIS (Type 027). The Retina IIIS had an all new body that was both taller and wider than the Retina IIIC that preceded it. It also used the same interchangeable lens mount which was available on the IIIC and the Retina Reflex models.

Despite a somewhat simplified design, the IIIS wasn’t any cheaper than the IIIC that preceded it. With a list price of $175, the IIIS was still out of reach of the average consumer. In an effort to bring costs down, in 1959, a smaller non-folding Retina known as the IIS was released that was built on the body of the Retinette series. Although comparable to the larger IIIS, it lost the interchangeable lens mount, and had only a fixed Retina-Xenar 45mm f/2.8 lens.

By 1960, Single Lens Reflex cameras like the Nikon F, Asahi Pentax, Minolta SR-2, and Canonflex had taken the professional market away from rangefinders, and as a result, the need for a high-spec and expensive rangefinder was not what it used to be. For companies like Kodak AG who still sold them, the desire to simplify both the design and the ease of use was critical to keep the public’s interest. From this point forward, all rangefinder Retinas that would be sold emphasized simplicity over precision. While 1960s Retinas were hardly cheap, they were seen by many to be a step backwards from the precision built instruments they once were.

Perhaps in an effort to capture the attention of the novice photographer, in 1960 Kodak would release the first Retina capable of auto exposure. The Kodak Retina Automatic I (Type 038) was built on the same body as the Retinette IA with a Gossen selenium cell exposure meter which was coupled to the iris in the fixed Retina-Reomar 45mm f/2.8 lens. All Retina Automatic cameras had shutter priority auto exposure, relying on light readings from the selenium meter. They were still entirely mechanical cameras that did not require the use of a battery, making them one of the highest quality battery-less cameras capable of auto exposure.

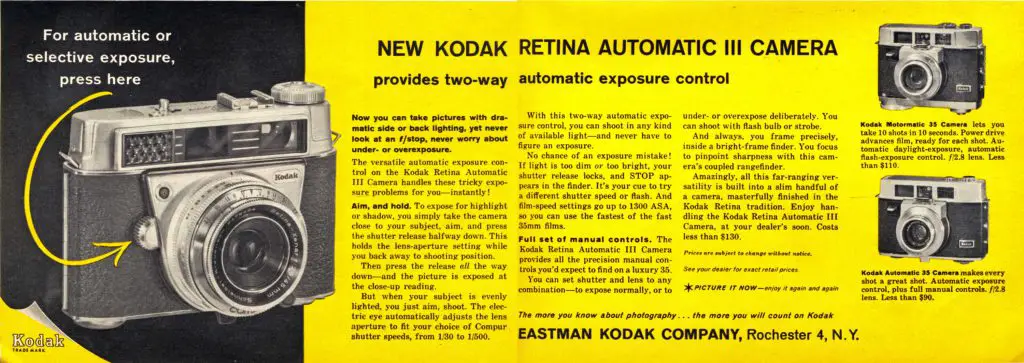

The ad above from the April 1961 issue of Modern Photography lists the price of the Kodak Retina Automatic III as $130 which when adjusted for inflation is around $1050 today making it quite an expensive camera. Kodak’s advertisements of the time heralded the Automatic’s ease of use along with the “masterful finish in the Kodak Retina tradition” which clearly references the reputation of all prior Retinas.

Between 1960 and 1963, two more Retina Automatic models would be released, known as the Automatic II (Type 032) with a better lens, and the Automatic III (Type 039) with both the better lens and a rangefinder. The three Retina Automatic models would represent the last of the true Retina cameras, and the only with auto exposure. After the three models were dropped in 1963, the Retina name would be used once again in 1966 in two completely unrelated plastic cameras known as the Retina S1 and S2 which were inexpensive cameras that bore no resemblance to the earlier models.

Today, the Kodak Retina series is very popular with both collectors and film photographers. Some of the more desirable models like the first Type 117 and the “big C” models of the 1950s can fetch hundreds of dollars on the used market. Even the less desirable scale model versions are still popular for their excellent build quality and optics. With the only exception being the final Retina S1 and S2 models, if you find any Retina camera at a garage sale or flea market, it’s worth picking up!

My Thoughts

I’ve owned over half a dozen Retinas over the years, some in better condition than others, but of the usable ones, I’ve generally been happy with the results of the images they make, yet I don’t often use them more than once. I find that the combination of small viewfinders on the older ones, and the occasional finicky control, makes me reluctant to throw one in a bag on a spontaneous trip to a state park or downtown Chicago.

Since I value a large viewfinder, the largest ones on a folding Retina are in the IIC and IIIC (big C) models, but those are also two of the most expensive Retinas on the used market and often go for quite a bit higher than I am willing to spend. One day while browsing Chris Sherlock’s excellent retinarescue.com website, I read about the Retina Automatic series. I found them to be a curious late addition to the Retina family. They share a similarly large viewfinder to the big C folding Retinas, but they also have the added feature of Auto Exposure which I had never considered for use in a Retina.

A quick search on everyone’s favorite online auction site and I found a surprising number of Retina Automatics for affordable prices. The issue though, especially with the later Retinas is whether or not they work. All Kodak Retinas have a reputation of being some of the more difficult classic cameras to repair, so if you ever run into one that doesn’t work, fixing them is not for the faint hearted. I’ve taken apart early Retina Is with little to no problem, but my attempts at fixing a IIIc and a Retina Reflex did not go so smoothly. I waited until I found a Retina Automatic that the seller claimed to be in working condition before I picked up the one being reviewed here.

When it arrived, I was pleased to see that the shutter not only worked, but the selenium cell meter responded to light, which is important since the AE system depends on the light meter to work. Thankfully, the Retina Automatic shows it’s mechanical roots, and had the meter been dead, the camera would have still worked manually. This is one way in which the Retina Automatic is superior to other selenium cell based AE systems that were common in the late 50s and early 60s like the AGFA Optima and Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127.

My first impression of the Kodak Retina Automatic III when it first arrived was that it still felt like a high quality precision instrument like I had become accustomed to with earlier Retinas. The camera was mostly metal and had a solid heft to it that inspired confidence. The viewfinder was indeed large and bright. The camera has a neat little feature wherein the word “STOP” would appear at the bottom of the viewfinder and the shutter release would lock, when there wasn’t enough light to expose the image properly. I also didn’t mind the lack of an interchangeable lens mount, or a higher spec lens as I’ve found these Retina-Xenar f/2.8 lenses to be quite capable.

The one thing that really struck me as a curious omission was the complete lack of slow shutter speeds. The Compur leaf shutter only goes down to 1/30th of a second. I understand that perhaps it might have been difficult to auto expose slower speeds, but since the Retina allows for full manual control, it just seemed odd that there weren’t any slow speed options. Perhaps Kodak thought that the target customer who might buy an AE Retina might never need slow speeds. Whatever the reason, the Retina Automatic is limited to an outdoor only camera unless you are willing to use a flash. Although lacking a hot shoe, the Retina Automatic has a PC flash port and supports both flashbulbs at 1/30 and electronic flashes at any speed. With this limited range of shutter speeds, the “STOP” feature popped up often for me in anything other than well lit outdoor scenes.

The rest of the Retina Automatic III is pretty typical of other Retinas made in the mid 50s through the early 60s. The winding lever is on the bottom of the camera as opposed to the top, which is something I spoke about in my review for the Retina IIc where I said this is neither a pro or a con, its just different. The exposure counter runs backwards, meaning when loading in a fresh roll of film, you set it to the number of exposures left on the roll, and as you advance the film, it counts down to 1. When the exposure counter gets to 1, the shutter will lock, preventing you from taking another picture and possibly tearing the film out of the cassette. Finally, the door release is hidden under a ‘lock’ on the bottom of the camera that must be moved out of the way before opening the back of the camera.

Whether you are shooting the Retina Automatic III with auto exposure enabled or not, you can still use the meter readout on the top plate of the camera which indicates an appropriate aperture f/stop. There are also two red zones, one of which moves depending on your chosen shutter speed, which indicates the range of f/stops the meter can measure. If the needle is pointing at one of the red areas, the shutter is locked and the “STOP” signal appears in the viewfinder. While its not hard to understand what “STOP” means, this needle on the top plate of the camera is rather confusing. It’s not even totally clear that it’s giving you aperture sizes as the only visible numbers are 4, 8, and 16. Everything else is just a dot. While it was common for cameras of this era to have a top plate exposure readout, I found this to be rather useless and one of the few poorly designed features of the camera.

While shooting with the Retina Automatic III, I did notice a bit of play in the shutter release which I am not sure is normal, or whether my particular example is just showing signs of age. When pressing the shutter release, you can feel the actual shutter release lever wiggle a bit, and you can hear a cacophony of mechanical clicks and groans. The manual says you can half press the shutter release to lock in an exposure reading without actually firing the shutter, so I assume this is the linkage between the auto exposure system and the shutter release doing it’s thing. The shutter seemed to work properly during my first roll, but when taking into account the frequency of “dead Retinas”, it was something constantly on my mind, and it definitely “lessened the Retina experience”. Like I said, this is my only experience with this model, but I have to believe that if this is how all of them were, that it might have weakened the reputation of this camera compared to other models available at the time.

The entire Retina Automatic series was in production for a relatively short period of time. Was it because of it’s price, or that more and more people flocked to SLRs and cheaper rangefinders, or was there concern about the reliability of this model? I honestly don’t know. I haven’t found any period reviews of this camera that suggested quality control issues, but nevertheless, with the increased chances of finding a Retina Automatic in non-working condition and mine exhibiting this behavior, it is certainly not a camera I would suggest for capturing precious moments. It was a fun camera to use, but I question it’s dependability.

Despite the lack of slow speeds, and a questionable shutter release, it’s still worth noting that the Retina Automatic III is still a worthy camera to a collection. For one, it is a very handsome camera that looks just as great on your shelf as it does in your bag. There is something satisfying when using a fully mechanical camera that has no electronics and does not even need a battery. If you plan on shooting one (you should), condition is critical. This is not a camera you want to attempt to repair, and although guys like Chris Sherlock will work on them for you, the cost to repair them with shipping to New Zealand and back can be quite prohibitive for people on a budget.

It’s worth noting that there are two variants of the Retina Automatic III. At some point during the production run, Kodak used a larger Gossen light meter instead of a smaller one. It seems that this change was made near the beginning of production, but I was unable to find any reference to serial number or anything. There does not appear to be any functional improvement of the larger meter versus the smaller one so I don’t think one is better than another, but it’s something to keep in mind.

My Results

The Retina Automatic III is the first Retina I’ve ever used with automatic exposure and while the lack of automation hasn’t kept me from getting shot after shot of properly exposed shots on previous Retinas, I’ll admit to being a bit excited at the prospects of what a Retina with AE could be capable of. This could be the ultimate “zoo” camera. Compact, and well built, with a bright and easy to use rangefinder, excellent lenses, and automatic exposure.

I tend to use the term “zoo camera” often on this site to refer to cameras that you take with on a family trip to the zoo that are easy and unobtrusive to use, yet are dependable cameras who consistently get great shots. The thing is, I haven’t actually ever taken any of these cameras to the zoo, until now. I took the Retina Automatic III with me on an impromptu late March trip to Indianapolis where we went to the Indy zoo. If you ever have a chance to visit the Indiana state capital, I strongly recommend it. It’s in the dead center of the city and although not a large zoo, there’s enough to see and do there in a day, but isn’t so huge that you are completely worn out by the time you leave.

So loaded with a roll of Fuji 200, the Retina Automatic III became my first “zoo camera” that I actually took to a zoo. Would it wear that label proudly?

Ouch. It would appear that one of my first instincts when I first got this camera of a sketchy shutter release turned out to have some merit. There is clearly some type of metering or shutter issue with this camera. Of the 24 exposure roll, most shots were overexposed. Some only slightly, while others were extreme. In the gallery above, the first 4 shots were the best 4 from the roll, only a couple of which are representative of what a Retina camera is typically capable of. The rest had a mish-mash of issues.

What is odd is how many shots showed motion blur or were completely out of focus. While its plausible that the rangefinder was out of adjustment on this camera, I don’t recall any issues looking through it. The Retina Automatic III has one of the largest, brightest, and easiest to use combined viewfinders of any Retina in my collection. Also, since this is a shutter priority AE camera, I had control over what shutter speed I was using. I kept the camera at 1/125 for most of the shots, letting the camera control the iris size, yet many had motion blur in them like the one of the boy sitting in the baseball dugout. This suggests a sluggish shutter. A sluggish shutter could also be blamed for over exposed shots if it was left open too long. Perhaps that “grinding” noise I felt each time I fired the shutter was the result of something getting stuck or binding.

It would seem that in at least a few of the shots, the camera did OK, but still, the images appeared washed out and not typical of what I usually get with Fuji 200 film. I’m starting to wonder if I mistakenly used some other kind of expired film which would explain the muted colors. (Edit: I didn’t.)

In any case, the results from this inaugural roll were disappointing to say the least. Other than the grinding noises I felt when firing the shutter, there were no other hints that something was amiss while shooting with it. I would have never imagined that so many of the shots would have so many issues. I missed focus on an a startlingly high number of shots, several had excessive motion blur suggesting too slow of a shutter speed and almost every image was overexposed.

I’ve been disappointed with cameras before, but I really wanted to like this camera. Until now, I have had consistent good fortune with Kodak Retinas from the 1936 Type 119, to the awful to shoot Retina Reflex IV. This camera is in nice physical condition and has probably the best viewfinder of any Retina in my collection. Perhaps I could shoot this camera manually and have better luck, but if I did that, I might as well use any other number of mechanical Retinas in my collection.

Are my results typical of a Retina Automatic III? Probably not. I am sure that when this camera was first sold, it most likely produced consistently excellent images. This is one of the perils of reviewing old cameras. Many times I am able to get great results from them, but not always. When I can’t, it’s likely due to age or misuse over the years by some previous owner. But that brings me to probably the most important point if you are considering adding one of these to your collection. All 50+ year old cameras come with some level of risk as you simply do not know how the camera was cared for over the years. Retinas specifically are known to be fickle beasts and any time you pick one up, there is an additional level of risk simply due to the complex design of the camera. Finally, having to rely on something as fundamentally unreliable as a light powered selenium cell light meter to get the most important function of the camera to work is a trifecta of risk working against you. The promise of a large viewfinder Kodak Retina with auto exposure was definitely alluring, but it might have just been too much to ask.

The entire Retina family has a notorious reputation for not being easy to fix, so I doubt I’ll make any attempt to fix this camera myself. For now, it’ll just sit on my shelf looking pretty. Maybe I’ll sell it. Maybe I’ll take it out for one more roll in the hope that I have better luck the second time around. Until then though, I can’t in good conscience, recommend the Retina Automatic III, especially when pretty much every other Retina is so good.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Retina Automatic series represents a first and a last for Kodak. It was the first Retina to feature auto exposure, but it was the last in the line of the “true” Retinas. The camera is still mostly metal and feels good in your hand, plus it has one of the best viewfinders of any Retina I have ever used. The 6-element Schneider Retina-Xenar is just as capable as those found on any previous Retina and when in good working condition will reward you with excellent photos. The problem though is finding one of these in good working condition which is a tall task to ask for a 1960s Retina with a selenium cell based auto exposure. In my case, the results were disappointing, and perhaps with another sample, they might as well be better, but then again, I’ve never had trouble getting properly exposed images from other Retinas, so why even bother? | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.2 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Retina_Automatic_I_II_III

https://shotonfilm.wordpress.com/the-cameras-2/kodak-retina-automatic-iii/

http://retinarescue.com/retinaautomatic3.html

http://www.rangefinderforum.com/forums/showthread.php?t=123198

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/kodak-retina-automatic-iii.411468/

Great Read! I certainly looked forward to the reveal as you went through the motions of inspecting the camera and getting acclimated to it. It seemed you had a really good thing going, so it’s so unfortunate that results didn’t bear out what seemed to be an enjoyable shooting experience. I know it’s tough to write a review for a camera that doesn’t turn out giving you what you hoped, but you did a stellar job of staying the course.

My inference regarding the lack of slow shutter speeds is that by 1960, Kodak’s Nagel-made products were skimming them out. I have a 1961 vintage Retinette 1A that goes straight to “B” after 1/30. The one good part to this economy measure is that the annoying LV linkage is gone. Interestingly, looking at this Retinette, I notice a LOT of parts shared between these two cameras, right down to the film minder dial. Luckily yours doesn’t have the skimpy PLASTIC advance lever that the contemporary Retinette has. :

A friend asked me to undo the LVS linkage on his IIIc- was not hard, a little filing. I suspect the advance lever from an earlier camera can be substituted for the plastic wind lever of the later Retinettes.

The Xenar is a 4-element in 3-group lens, the Xenon is the 6-element in 4-group lens used on the Retina II series. The IIc and IIC used an F2.8 Xenon that was essentially the F2 lens with a truncated front element. The IIb and IIB have the 50mm Xenar.

The Automatic III is a well-made camera, those without working meters can be used in full-manual mode.

I have one for which I paid a few dollars off THE auction site. I took it to NYC last year on a weekend trip and got some nice shots out of it, shooting in auto mode. I agree, some were a little washed. I’ve bought several cheap folding Retinas. The older ones with knob-wind always work. The lever-wind folders are really a crap-shoot if they keep working. I’m taking a folding IIa I got at an estate sale on the Pacific Coast Highway next month, and also a Rollei 35 as back-up.

Good review. I’d say have the camera properly serviced and then come back with an updated review to see how it really does. Like you mentioned, when it was new, it likely produced excellent results. 50+ year old grease and dirt needs to be cleaned out. Nice to see the old selenium meter was still working though. The Kodak retinas are fascinating cameras. All the complexities they incorporated really were quite marvelous for the time. I’m also sure that Kodak intended for customers to have their camera cleaned and serviced periodically, especially someone considering spending a considerable what was a considerable amount of money. Thanks for the post.

Low output from a decaying selenium cell will cause overexposure. Try using a separate meter. The camera can be used manually and I am sure you’ll love the results.