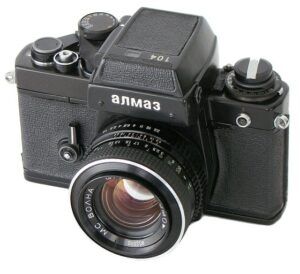

This is an Almaz (Алмаз) 103, a 35mm single lens reflex camera made by Leningradskoe Optiko Mechanichesckoe Objedinenie, or LOMO for short, between the years 1979 and 1986 in the former Soviet city of Leningrad. There were a total of four models in the Almaz family, but only the 103 was produced in large numbers with the other three being extremely rare. The Almaz 103 was intended to be a professional 35mm camera, with features such as an interchangeable viewfinder, motor drive coupling, vertically traveling metal blade shutter, and support for the Pentax K Bayonet Mount. Although the camera is heavy and vaguely resembles a Nikon F2, it is not a copy and should not be held to the same standard as that camera.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 LOMO MC Volna (Волна) coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: Pentax K Bayonet Mount

Focus: 1.5 feet / 0.45 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism with Interchangeable Focus Screen

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: No Shoe, FP and X Flash Sync, 1/60 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Viewfinder Blind, Shutter Lock, Battery Check Button, Double Exposure Lever, Mirror Lock Up

Weight: 1002 grams, 752 grams (no lens), 614 grams (no viewfinder)

Manual (in Russian): http://www.commiecameras.com/sov/35mmsinglelensreflexcameras/cameras/others/manuals.htm

How these ratings work |

The LOMO Almaz 103 was a serious attempt by the Soviet photo industry at building a professional 35mm SLR that compared to Japanese models. Although about a generation behind in terms of features, the Almaz 104 mostly accomplished it’s mission. Using the Pentax K-mount, it was compatible with a huge number of lenses, and with features like interchangeable viewfinders and a vertically traveling metal shutter, it was quite a bit more useful than many other Soviet SLRs. These cameras are uncommon however, especially in the United States, so if you’re interested in picking one up, be prepared to open your wallet. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 6.0 | ||||||

History

Throughout it’s existence, the Soviet Union made many cameras. Rangefinders, SLRs, medium format folders, cheap point and shoots, even an instant film camera. For most collectors, Zenits, Zorkis, Kievs, and Smenas are the most common but there are quite a number of less known cameras like the Narciss, Voskhod, and Iskra which are worth adding to your collection as well.

Of all the different types and styles of cameras that the Soviet Union was known for, one type of camera they didn’t have much success with was the professional 35mm SLR. Now, this doesn’t mean that no one tried to build a 35mm SLR for the pros, as models like the KMZ Start and the Kiev 15 were produced with aspiring semi-professional specs, but neither of these cameras sold very well or were very successful.

The reason the Soviet Union was never successful at professional level cameras is complicated. For starters, many of the federation’s factories weren’t equipped with the highest skilled labor. Most factories where cameras were built prioritized speed and volume over quality. In order to build a camera with the highest specs, also requires the highest quality, and while there certainly were examples of high quality cameras in the Soviet Union, it wasn’t a typical priority. Another reason, which is beyond the scope of this article, is in the economy of the country. This is why cameras like the Smena and Zenit were produced in the millions, far beyond the number of people who could buy them. Without the benefit of capitalism, supply and demand didn’t exist in the same way it did in the west where some high volume products sold to the masses, but higher quality items could be sold to those with more money.

By the late 1970s, things started to change. Access to Japanese cameras increased as some photographers could apply to the state for procurement of Japanese cameras. The prices were generally quite high and you generally had to be well connected to even have a chance at getting something like a Nikon or Canon SLR. With exposure to cameras used by western photographers came more options for Soviet photographers.

In 1975, the office of the Soviet Minister of Defence set in motion plans to build a professional 35mm SLR for use by photojournalists that would compete favorably with Japanese cameras like the Nikon F2. The original order was to build up to 25,000 units per year of this new camera and be able to sell it at a price cheaper than what an imported camera would cost.

At the time, there were many factories where Soviet cameras were produced, and the one with the highest reputation was the Arsenal plant in Ukraine where the Salyut/Kiev medium format SLRs and Kiev 35mm rangefinders were produced, but they lacked the know how to create an all new camera from scratch. KMZ in Russia had the highest output of all Soviet camera producing factories, producing millions of Zenit SLRs and Zorki rangefinders, but they were not allowed to create something that might risk the reputation of their current models.

Finally, the LOMO plant in Leningrad, Russia was tasked with creating this all new photojournalist’s camera. There Anatoly Pavlovich Avdonin was appointed chief designer and the design of the shutter was entrusted to Mikhail Pavlovich Biyushkin. For the shutter, Biyushkin looked for inspiration from focal plane shutters used in other Soviet cameras, but decided to build an all new design from scratch.

Within two years, the new camera started to take shape and in 1977, the name Almaz (Алмаз) was chosen, which translates in English to ‘Diamond’ as it was thought this new camera would be the pinnacle of the Soviet camera industry, like a diamond.

From the very beginning, three models were planned, each with different features targeting a different level professional. The main body of the camera would be modular, allowing it to be equipped with varying levels of features. Whether you had the highest spec or lowest spec model, the internal structure, including the shutter and lens mount would be the same. For the lens mount, LOMO chose the Pentax K bayonet mount rather than build an all new mount unique to this camera. The idea of a Soviet SLR using a Japanese lens mount was first used in 1975 by the Kiev-17 which used the Nikon F bayonet. By using an already established lens mount, this would eliminate the burden of the factory having to come up with an all new lineup of lenses, and could instead import, or copy, existing Japanese lenses. The reason the Pentax K mount was thought to have been chosen was that there were no international patents that applied in the USSR for it.

According to an article on the Almaz series over on photohistory.ru, it is suggested that each of the three models would be available based on the needs of the user’s job specifications. The top of the line model, eventually called the Almaz-101 would be the most feature rich model and would be built for a supervisor-level photojournalist, perhaps working for the national media, or perhaps even the government. In addition to a shared inner body, interchangeable viewfinder, and removable film back, features unique to the Almaz-101 were:

- Aperture Priority Automatic Exposure

- Electromechanical Shutter with speeds from 8 – 1/1000 (some sources suggest it’s slowest speed was 30 seconds)

- Full information viewfinder showing shutter speeds and selected f/stop

- Premium lens (unknown what was planned)

- Unknown price

The middle model, the Almaz-102 would be for the reporter of a regional newspaper and would downgrade the features from the Almaz-101 to:

- Match Needle exposure meter located in the prism, similar to the Nikon F2 Photomic prism

- Mechanical Shutter with speeds from 1 – 1/1000

- Partial information viewfinder showing selected speed and match needle or LED display

- MC Volna 50mm f/1.4 lens

- 650 Roubles

The final model, the Almaz-103 would be a camera for a lower level, or district photojournalist and would downgrade the features from the Almaz-102 to:

- No exposure meter

- Mechanical Shutter with speeds from 1 – 1/1000

- Simple pentaprism with no information

- MC Volna 50mm f/1.8 lens

- 350 Roubles (quickly lowered to 295 Roubles)

In 1979, the first pre-series prototypes of the Almaz-103 were presented. That it was the most basic model is likely why it was the first to be shown. Although internally called the Almaz-103, the faceplate of the camera had the LOMO logo. Whether this was part of the original design or indicative of the prototype nature of the camera is unclear but looking at the early LOMO cameras, apart from the nameplate, nothing else appears to be different from the final version.

Also in 1979 the first Almaz-102 cameras were produced. These were made in very small numbers as the factory struggled with the electronics. As a whole, the Soviet camera industry did not have a lot of luck with electronic cameras as they both lacked the experience but also the raw materials needed to produce them in sufficient quantities.

Both the Almaz 102 and 103 prototypes were previewed in Soviet photographic publications and shown at a few select trade shows. The response was very positive as the photographic press was extremely excited at the chance of a Soviet built camera with the features promised, especially from those still using old rangefinders or Zenit SLRs. The price of the Almaz 103 at 295 Roubles, while still expensive was at least within reach of many.

Pretty quickly after the release of both the Almaz-102 and 103 models however, flaws in the design became very evident. Early cameras often had to be sent back in for service to be repaired. The simpler 103 model was the most reliable as there was less to go wrong but even it was unreliable at the beginning.

While the quirks of the Almaz-103 were eventually worked out, the Almaz-102 still struggled, and plans for future production were scrapped. In total, only 63 were built, making them extremely difficult to be found today.

The fate of the Almaz-101 was even worse as the prototypes never came close to reaching the level of functionality promised. A single non-working prototype was thought to be built and is currently in a museum. Externally, the camera looks very rough and doesn’t match drawings of the prototype which were originally shown in in 1979. According to this Russian language page on the Almaz series, the one Almaz-101 prototype doesn’t even have the correct shutter, and is thought to have a Seiko transplant in it.

This left the Almaz-103 as the lone model of the original three to be produced beyond 1980. A total of 9508 cameras were made through 1986 when it was discontinued.

In 1986, a fourth Almaz model, called the Almaz-104 was planned, which would resurrect the Almaz-102 with it’s prism mounted exposure meter, but with a simplified display showing exposure information with red, yellow, and green LEDs. Despite a simplified feature set and the benefit of six more years of understanding how to make an electronically metered SLR, the Almaz-104 never made it beyond the prototype stage, with only 10 thought to have been made.

By the end of 1986, interest in continuing to pursue a premium level 35mm SLR had disappeared. Difficulties with the design and production of the Almaz meant that if another serious attempt were to have been made, it likely would have required a completely new re-design, something the struggling industry couldn’t afford to do.

Another possible explanation, which is my own theory, is that it was getting increasingly easier to get Japanese cameras in the country for those who really wanted them, and by 1986, Japanese 35mm SLRs had advanced so far beyond what the Almaz offered, made it an easy choice to go another route.

Today, Soviet cameras of almost every type are collectible. The Almaz series, specifically the Almaz-103 are highly sought after as they represent one of the most advanced Soviet SLRs ever made. Although not as reliable as a Zenit or even the Kiev 17 and 19 series, when found in working order are good shooters. With support of the Pentax K mount, you can either use one of several Soviet lenses made for them, or any Pentax K-mount lens produced. Some sites online suggest there are incompatibilities between the Almaz’s mount and actual Pentax lenses, but in my research for this article, I was able to easily swap SMC Pentax K-mount lenses between this Almaz-103 and both a Pentax K1000 and MX without issue.

The Almaz is a large and heavy camera that is modern enough to not look at primitive as other Soviet SLRs, but still maintains that “built like a tank” reputation that Soviet cameras often have. They’re fun to shoot, and look great on a shelf, so if you ever have a chance to pick one up, especially if you are in the United States, I definitely recommend it.

My Thoughts

Using a tactic I’ve covered numerous times in my Buying Cameras on eBay article where I say patience and persistence are the keys to getting any camera you want, doesn’t always work. While it works a large amount of time, sometimes there are some cameras where you need to put the word out to some fellow collectors and borrow some stuff. Thankfully, with less common Soviet cameras, I have my friend and fellow blogger, Vladislav Kern to help me out when I run out of patience and persistence!

In September 2022, I made the trek up to the far northwest Chicago suburbs to visit the ussrphoto.com headquarters and before leaving, I picked a couple of cameras I wanted to play with, and one was this Almaz-103. In the presence of such a massive collection of Soviet gear, I had the benefit of selecting one that appeared to be in perfect working order. Even when new, the Almaz cameras weren’t noted for having the best reliability, but adding four decades of age only makes things worse, so I’ll start with the typical disclaimer here in that if this article prompts you to seek out an Almaz-103 of your own, you really want to confirm functionality first.

Before I go any farther, I want to address something that I read over and over again online whenever someone talks about the Almaz. In the history section above, I state that during the initial planning of developing a new Soviet professional 35mm SLR, that it would compare to the Nikon F2. At the time, the Nikon F2 was the most popular and highest class professional 35mm SLR out there. Even for a country as isolated as the Soviet Union, they were aware of the Nikon F2’s existence, so using it as a measuring stick for their own camera made a lot of sense.

I can also understand how if someone were to take a glance at the Almaz-103 without having seen a Nikon F2 recently, they might think, “yeah, that sorta looks the same” as the top prism shares some similar lines to the F2’s Photomic prisms, the bodies are all black like many F2s were, and both appear to share a similar heft.

Beyond these passing similarities, I do not think it is accurate to say the Almaz-103 is a copy, clone, or a remake of the Nikon F2. There are far more differences between the two than similarities, much like the Nikon F isn’t a copy of the KW Praktina, although both cameras do share some things in common.

- Dimensionally, the cameras are similar. Height and depth are about the same, but the F2 is a couple mm wider. On the scale, the Almaz-103 body (no lens, but prism attached) comes in at 752 grams and the Nikon F2 is a bit heavier at 844 grams.

The Almaz focusing screen (right) is much smaller than the one used on the Nikon F2 (left).

- Although both cameras have interchangeable viewfinders and focus screens, they are not compatible with each other. Both cameras lift off vertically and require two separate contact points to remove, but the way in which the prisms connect is not the same, and the focus screens are different sizes, meaning you cannot swap between the two.

- The Nikon F and Pentax K bayonets are obviously different, but the manner in which the lens couples to the camera is different as well. The Almaz has the internal aperture coupling that the K-mount allows, whereas Nikon F-mount lenses of the F2’s era required an external coupling via the bunny ears. In 1977 Nippon Kogaku released the Ai system in which lenses coupled to the meter using a ring around the lens, the Almaz does not support this as it doesn’t need to.

- The shutters are completely different. Nippon Kogaku used a tried and true horizontally traveling titanium foil shutter that was based off the ones from both the Nikon F and the Nikon SP. The Almaz uses a two blade vertically traveling metal blade shutter that externally looks like an East German Praktica design. Despite traveling vertically, the Almaz still has a slower X-Sync speed of 1/60 compared to the F2’s 1/80 speed. In addition the Nikon’s top shutter speed is 1/2000 compared to the Almaz’s at 1/1000.

- The list of features for the Almaz is much smaller than the F2. Now to be fair, the Almaz-103 I am reviewing was intended to be the lowest spec of the three models initially planned, so it is possible that had the Almaz-101 made it to production, it would have narrowed the gap, but comparing the 103 to the F2, the 103 lacks any sort of metering, mirror lockup, and a shutter release lock. Furthermore, although both cameras support a body mounted flash connection and a motor drive coupling, I do not believe that any such accessories were ever made.

- Finally, in terms of quality control, there simply is no comparison. The Nikon F2 is one of the most reputable and highest quality cameras ever made. It can survive wars, arctic temperatures, desert heat, and based on the number of how many are still working today after nearly a half century of existence, there is no comparison. The Almaz-103 is a notoriously unreliable camera, and finding someone who can service them is difficult.

That said, it’s not exactly fair to keep talking about the Almaz-103’s shortcomings. There is a reason almost no one built another camera like the Nikon F2. For a company and a country not known to compete in the pro 35mm SLR market, I give them credit for a pretty decent first attempt. If the Almaz had come out a bit sooner and was successful, it would have been very interesting to see what an Almaz-2 might have been like.

Back to the camera though, one thing the Nikon F2 and Almaz 103 do share is familiarity. It is clear the Soviet camera industry got the message that coming up with strange interfaces and awkward controls was not doing them any favors (I’m looking at you, Kiev-15 TTL!). The Almaz-103 definitely has a Japanese inspired design to it, so if you were ever in a situation where you had to shoot a roll of film at a moments notice without ever having held one before, you would have no problem as all of the camera’s controls operate and are located exactly how and where you’d expect them.

Up top, the Almaz-103 has the pull up rewind knob with flip out handle and a GOST film speed scale beneath it. On the Almaz-103 this serves simply as a reminder as there is no meter in this camera, but since all three Almaz models were known to have the same chassis, I assume this dial was used to set the film speed on the other metered models. Beneath the rewind lever, but above the film speed dial are two contact points for mounting a flash. Although different from the flash contact on the Nikon F2, it appears to work similarly, but I cannot be sure as I have never seen a flash unit for the Almaz.

The interchangeable prism dominates the center of the top plate. Like the Nikon F2, removing the prism isn’t very intuitive. Rather than using a reverse sliding design like Topcon and Miranda, you must simultaneously press on a plastic lever behind the prism and a black button on the front edge of the side of the prism while lifting up. With the prism off, you can use the camera at waist level without anything attached as long as you shield the focusing screen from extra light. To change the focus screen, press in on the round chrome button on the rear of the camera, while holding the camera upside down.

To the right of the prism is the shutter speed dial with speeds from 1 – 1/1000 plus Bulb. You can go from Bulb straight to 1/1000 without having to turn it the complete opposite direction. Beneath the shutter speed dial is a black lever which acts as a “T” setting for timed exposures. At first, I thought this lever was a shutter release lock, but it does not appear to do that. With the shutter speed dial set to any speed from 1 – 1/1000 and this lever to the right position, pressing the shutter release fires the shutter as normal, but keeps the shutter release in a lowered position, which you cannot press again until you return this lever to it’s original position. With the shutter set to Bulb however, pressing and holding the shutter release while moving this lever, keeps the shutter release pressed and the shutter open. Strangely, I had difficulty getting this lock to release. I eventually got it, but assume this is a failure point of the camera, so I didn’t want to keep messing with it.

Edit 3/15/2023: After posting this review, reader Louis P in the comments below explained the black lever above the shutter speed dial is an intentional double exposure lever. This example didn’t seem to work this way, but it is very likely it is not functioning correctly. At the very least, this appears to be a weak point of the camera that if you manage to get one that works, I would recommend not touching it.

Next is the cable threaded shutter release button, film advance lever, and automatic resetting exposure counter showing how many exposures have been made on a new roll of film. In between the film advance lever and the shutter speed dial is a small black button whose function I am uncertain of. I tried various combinations of changing shutter speeds, firing the shutter and advancing the film with and without it pressed and nothing seemed to change. Either this is a feature of the camera that is no longer working or it might be a provision or a feature intended for the Almaz-101 or 102.

The bottom of the camera has the mechanical coupling and two electronic connections on the opposite side for a motor drive which was never made for the Almaz. To the right of the mechanical connection is the rewind release button, and in the center, directly below the lens mount is a metal 1/4″ tripod socket. Notice that compared to a Nikon F2, there is no key for unlocking the film compartment. The Almaz-103 uses the more modern method of pulling up on the rewind crank to open the rear door, but that also means that the camera cannot use reusable metal cassettes.

The back is where the Almaz looks most closely like the Nikon F2 as both cameras have a similar chrome viewfinder release to the left of the round eyepiece, the eyepiece itself is internally threaded for connection to various eyepiece accessories. The center of the door has a square film box end window to be used as a reminder of what film is loaded in the camera.

The sides of the Almaz are pretty uneventful with nothing other than a pair of chromed metal strap lugs. Each lug is angled forward so that when hanging from your neck with a lens mounted, the camera won’t tip forward.

Lifting up on the rewind knob allows the right hinged film door to swing open. Film transport is from left to right onto a fixed and multi-slotted take up spool. Above and below the film gate are twin polished film rails. In between the bottom two is the camera’s serial number, which follows a common Soviet practice of including the camera’s year of manufacture as the first two digits.

The film door is removable via a sliding pin in the door hinge. Inside the door is a large black metal pressure plate covered in a grid of divots which help reduce friction as film passes over it. So the left of the door is a chrome roller which helps maintain film flatness as it is being transported. Like many other SLRs of it’s era, the Almaz-103 uses foam light seals in the door channels, the door hinge, and above and below the door latch which on this example have all rotted away. Before shooting these cameras, it would be advised that you replace them, or risk getting foam material stuck in the shutter or allowing light to leak onto your film.

Looking down upon the MC Volna lens, the arrangement of aperture control and focus is exactly the same as all other K-mount lenses I own. Aperture f/stops from f/22 to f/1.8 are selected on a plastic ring with positive click stops. The rubber coated focus ring turns very smoothly and with little wobble, and has distances measured in feet (green) and meters (white). Between the focus and aperture rings is a fixed yellow depth of field scale.

Removing the K-mount Soviet lens is the same as any other K-mount lens. A small black button near the 8 o’clock position around the lens mount releases a lock, allowing you to twist the lens counterclockwise to remove it. Putting it back on is the opposite of removing it, except clockwise.

Below the lens release is a depth of field preview button which cannot be locked into position. The lens will remain stopped down for as long as you maintain pressure on the button. To it’s left is the mechanical self-timer lever.

The self-timer operates independently of the shutter release. To activate it, a small chrome button in the center of the lever must be pressed with the shutter already cocked. Pressing this button with the shutter uncocked will only allow the lever to travel part way. Using a stopwatch, a full swing of the self-timer takes 7 seconds before the shutter fires, which is a bit shorter than the 10 second delay on other cameras. Moving the self-timer part of the way does not appear to allow for shorter delays. This could be by design, or possibly age as self-timers can often be unreliable on old cameras.

The viewfinder on the Almaz-103 is one area of the camera that is very different from the Nikon F2. For starters, with prescription glasses, I cannot see all four edges of the visible image in the Almaz, whereas I have no problem with that on the Nikon. Although both cameras offer interchangeable focus screens, the one included on most F2’s I’ve seen have a split image focus aide in the center whereas the Almaz gets by with just a microprism circle. Strangely, no matter what I point both cameras at, the image is never sharply in focus in the Almaz-103. The entire focus screen appears to be optically blurred in the Soviet camera, which is not at all like any other SLR I’ve used. Inspecting the focus screen and prism, I do not notice anything that looks out of sorts. The screen is not installed upside down, or is the prism damaged, so I have no explanation for why this is the case. In the gallery above, I used my smartphone to capture the images of both in and out of focus to better show the microprism circle. It is also worth noting that my smartphone had no trouble seeing all four edges, whereas with eyeglasses on, I was unable to.

Further compounding matters is that the viewfinder is darker than any Nikon I’ve used, even going back to the original Nikon F. Looking through the viewfinder of other Soviet cameras, in terms of brightness, the Almaz-103 is similar to a 1960s Zenit-E, which isn’t exactly good company for a camera produced well into the 1980s.

For me, the Almaz-103 is less a copy of the Nikon F2 as it is heavily inspired by it. I would suspect that at whatever time this project began, engineers and designers all got together to decide what what they wanted to build and had a conversation saying something along the lines of “We know we can’t build a camera exactly like the Nikon F2, but let’s get as close as we can without trying too hard.”

The Almaz-103 has a lot going for it. It’s use of the Pentax K-mount was a great decision as opposed to yet another unique Soviet mount as you can use this camera with a huge number of available lenses. If the MC Volna is the only lens you have, you’ll likely be very happy with it. The camera is heavy and compares favorably with a mid 1970s mechanical SLR. If that’s all you want in your Soviet SLR, the Almaz-103 is the camera for you. But is it for everyone? Keep reading…

My Results

Wanting to get the full Soviet experience, for the first roll of film in the Almaz-103, I chose Smena Foto 100, a panchromatic black and white film made in Shostka, Ukraine. The roll of film was of unknown expiration as it came to me in a bulk lot of film which I’ve had sitting in a temperature controlled location in my basement. I have no idea of the storage conditions of the film, but I figured whatever distress the film might have, would fit the reputation of a Soviet camera. Adding to the experience, I would shoot most of the roll during the winter in Siberia….err, I mean Northern Michigan, where snow had fallen as far as the eye could see!

While shooting the Almaz-103, things seemed to work mostly OK. A few times near the beginning of the roll, it felt like the film advance was a little tougher than I would have expected, but everything seemed to get better and I finished the roll.

After developing the film and removing it from the Paterson tank, I noticed that the camera clearly had some transport problems through the first 6-8 exposures, as most were overlapping. I scanned those overlapping images and shared them below. After the 8th exposure however, the film transport problem mysteriously went away and the rest of the images were spaced correctly.

One generalization I can make about Soviet cameras is that almost always true, regardless of the operation or the condition of the camera, is that the lenses are usually very good. You can say a lot of things about Soviet camera build quality, but one thing is for sure, they did a good job making lenses. The images from the Almaz-103 stuck with that pattern as they turned out very good.

The 6-element MC Volna performs about as good as other 6-element Japanese or German lenses. I’m not one to pixel peep so it’s plausible that when adapted to a 48 megapixel full frame digital camera, I might be able to detect some minor irregularities between this and other lenses, but in these black and white scans from my Epson flatbed scanner, they look pretty good to me. Sharpness was excellent in the center to the edges with only a very slight hint of vignetting, contrast was good, and there were no optical anomalies often associated with lesser lenses.

I can’t speak for the accuracy of the lens on color film because I only shot this one roll. I usually like to shoot both color and black and white images on a camera, but quite simply, I did not like the Almaz-103 enough to want to do another roll. The ergonomics were fine, all the controls were in the locations that I expected them to be, and while I’ll stand firm that the build quality is nowhere near that of a Nikon F2, it was good enough.

If I was paid to make photographs in the Soviet Union in the early to mid 1980s when this camera was in production, I likely would have been excited to try one out. Even if Japanese cameras were possible to get, they probably would have been out of reach for all but the most well connected people, so the Almaz would have been the best I could get.

As a collector today, I have the benefit of hindsight to compare this side by side with a Nikon F2 and there is no comparison, but for photographers back then, they wouldn’t have known any better, so some of the camera’s shortcomings likely wouldn’t have been as obvious.

I had several complaints about the camera, all of which could be forgiven when taken in context of a low production Soviet SLR, but there was one thing I absolutely hated about the camera, which was it’s viewfinder.

This being the only working Almaz-103 I’ve handled, I’ll concede that perhaps there was a fault with this camera, but I really struggled to see focus through the viewfinder. No matter how close I held the camera to my face, I could not see all four edges of the viewfinder while wearing prescription glasses. I found the viewfinder to be darker than I would have expected from a camera made in the 1980s, but by far, the softness of the viewfinder constantly hindered my enjoyment of the camera.

I didn’t love the Almaz-103, but that doesn’t mean you wouldn’t, and it certainly doesn’t mean you shouldn’t add one to your collection if given the chance. There is a certain curiosity of a camera that tried to compete in a segment not often attempted by the Soviet photo industry, and there certainly aren’t too many Soviet lenses in the Pentax K-mount, so whether you want to shoot one, or just like it’s historical context, if you get a chance to buy one at a reasonable price, you should probably do it, as these don’t show up for sale often.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Almaz

http://www.sovietcams.com/index1d3a.html

http://www.photohistory.ru/1207248190560165.html (in Russian)

http://www.photohistory.ru/index.php?pid=1660417880019169 (in Russian)

http://www.xalmaz.narod.ru/sf9189x.htm (in Russian)

https://sovietcameras.org/almaz/

https://fotoussr.ru/cameras/almaz-103/ (in Russian)

Very informative review of a family of Soviet SLRs most of us have never seen nor used.

You do know that Asahi launched the K mount with zero licensing fees, in hopes of establishing it as a global standard and the industry-wide bayonet successor to the M42. In mathematics, “K” = universal.

I did know the K-mount was meant to be the new universal standard, but your factoid that K was chosen as it means universal in mathematics completely eluded me until now! Do you know if that’s definitely why they chose it, or is it a convenient coincidence?

Hello Mike, thank you for this review, I have an Almaz 103 and his own manual and I can tell you that the black lever near the shutter speed dial is a multiexposure lever. First take a picture, then pushing the little black button will unlock the lever and you can set it to the right. It will stay here and you will be able to cock the shutter without advancing the film as many time as you want. When you want to go to the next picture, push again the little black button and set the lever back to the left! It work like this on mine and is described like this on the manuel. You might had film transport problems if you used the multiexposure lever…

Louis, thank you for the additional clarification on that lever. This having been the only Almaz-103 I had handled, it’s function stumped me, and almost certainly wasn’t working correctly. A double exposure lever does make sense though. It does seem like a weak spot of the camera though, so my advice to anyone reading this, is if you have one, just don’t touch this lever! 🙂

Привіт, Майк! Дякуємо за іншу інформовану та точну статтю. Мені подобається широкий спектр камер, які ви переглядаєте. Прості механічні камери є одними є одними є моих улюблених, тому я вважаю російськими прийнятними. Вони були були націлені на населення, яке не могло доз волити собі і мали обмежені очікування, тому я приймаю их як такі. Принаймні, вони були міцними та легко ремонтуються! …Кайлін

Hi Mike! Thanks for another informed and accurate article. I love the wide range of cameras you review. Simple mechanical cameras are one of my favorites, so I consider Russian ones to be acceptable. They were aimed at a population that couldn’t afford it and had limited expectations, so I accept them as such. At least they were durable and easy to repair! …Kaylin

Thank you sir! I appreciate the feedback, especially from native language Russian speakers! I love cameras made in all countries and want to do them all justice! 🙂

How interesting – great review, Mike! I visited East Berlin frequently in the early 70s and observed that there was a ready supply of USSR-made photo equipment – lenses, cameras, etc. available there. I’m assuming that Pentacon cameras and Zeiss Jena lenses were available in the USSR as well. I wonder why they didn’t just try to rework the Praktica VLC cameras to suit their purposes. It was already a much superior camera (I’m thinking, after reading your review) and it would seem to be a much more cost-effective way to go, rather than starting from scratch. They could’ve easily attached the K-mount lens mount instead of the M42, if desired, or even made both available as an option. The Aus Jena Zeiss lenses for the Prakticas were superb, too. All were produced within the Soviet system. What am I overlooking with this?

Reworking the VLC or any of the later Praktica L-series cameras would have probably been a good idea, but that’s just not how the Soviet photo industry rolled. In every example (except the 35mm Kiev rangefinders) in every example where a Soviet factory built a camera that was similar to someone else’s, they always did it their own way and I think the Almaz was no different. In addition to that, I believe the Almaz (translated to ‘diamond’) was supposed to evoke some national pride as a professional camera that could compete with the Japanese. To build a flagship camera that was build using East German parts would not have accomplished that. Of course, that’s just my own guess…

The main reason why LOMO stopped producing this camera was its high production cost. In the mid-80s, USSR enterprises switched to self-financing and stopped receiving subsidies from the government. With the production cost of one camera being over 400 rubles, the set price for the Almaz was 285 rubles, which created a huge loss for LOMO.