This is a Minolta SR-2, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera produced by Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. in 1958. The Minolta SR-2 was the very first SLR released by Chiyoda Kogaku, launching an era of highly successful SR-mount SLRs that would last through the 1980s. Despite being the first ever Minolta SLR, the camera had a number of advanced features that were not yet standard on other SLRs of the era, such as an instant return mirror, support for automatic diaphragm lenses, and the ability to open the film compartment by lifting up on the rewind knob. The SR-2 was produced for only a short period of time as it was quickly replaced by the SR-3 which was a nearly identical model, but added support for a clip on exposure meter.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 55mm f/1.8 Minolta Auto Rokkor-PF coated 6-elements in 5-groups

Lens Mount: Minolta SR Bayonet

Focus: 1.75 feet / 0.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism w/ Fresnel Matte and Split Image Focus Screen

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Clip On Cold Shoe w/ FP and X Flash Sync, 1/50 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 934 grams, 674 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_sr-2.pdf

How these ratings work |

Despite being the very first Minolta SLR, the SR-2 is a very modern feeling camera with excellent ergonomics and familiar controls. The 60+ year old Rokkor lens renders sharp and beautiful looking images as good as Rokkors that came decades later. Despite being a first attempt, the designers who created this camera avoided the pitfalls of strange controls and poor design choices that many first cameras had. The Minolta SR-2 does not feel like a first SLR from 1958, and that’s one of it’s best features. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.3 | ||||||

History

When the topic of innovative and historically significant 35mm SLRs comes up, many of the same cameras get mentioned. Of course the Nikon F from 1959 is one of them as it set the standard of what a professional SLR should be, plus it set in motion Nikon’s dominance of the SLR era that would last more than a quarter century before any real challengers came along. The Asahiflex is another that frequently gets mentioned as not only the first successful Japanese SLR, but also that it had the first quick return reflex mirror and it was the progenitor of the hugely successful Pentax line. And speaking of firsts, who could forget the Ihagee Exakta, which was the first commercially available 35mm SLR and was the only option for nearly two decades before any serious challengers would come along.

One camera that isn’t as commonly mentioned with the same reverence as those other cameras is the Minolta SR-2, Chiyoda Kogaku’s first Minolta SLR. Until that time, the Minolta name had been used on rangefinders, twin lens reflexes, press cameras, and even a few folding cameras.

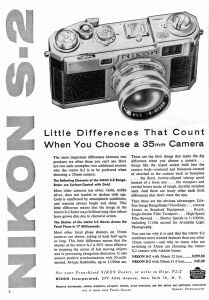

In some ways, the SR-2 was similar to the Nikon F in that it didn’t really feature too much all new technology, as most of the camera’s features like an instant return mirror, lenses with semi-automatic diaphragm, self-timer, single piece non-rotating shutter speed dial, automatic resetting exposure counter, and a quick bayonet lens mount, all had appeared on cameras that came before it.

In some ways, the SR-2 was similar to the Nikon F in that it didn’t really feature too much all new technology, as most of the camera’s features like an instant return mirror, lenses with semi-automatic diaphragm, self-timer, single piece non-rotating shutter speed dial, automatic resetting exposure counter, and a quick bayonet lens mount, all had appeared on cameras that came before it.

Like the Nikon F, the SR-2 was significant in that it included ALL of those features, into a single and easy to use 35mm SLR with a modern and ergonomic layout which would set the standard for 35mm SLRs for decades to come. For someone only familiar with SLRs of the late 20th century, picking up an SR-2 would feel familiar unlike an Exakta or some other early SLR.

Amazingly, for how much of a leader Chiyoda Kogaku was in the 20th century photographic industry, finding historical information about the development of the SR-2 was very difficult for this article. I scoured my usual sources for information, old photo magazines, Google Books, the Wayback Machine, plus a large library of camera books I have access to, and there was nothing about the SR-2 other than short previews of its release in 1958 and a single sentence in the “Minolta SR-T Manual” by John Neubauer and Robert Moeser that said work on Minolta’s first SLR began in 1953.

During my research for this article, I posted in a Minolta collectors group on Facebook looking for information, and two members, Maury Jacks and Andrea Aprà directed me to some scans from a Japanese language book published in 2011 called “Aim for Leica” by Kamio Kenzo who was an engineer working for Chiyoda Kogaku during the era in which the Minolta SR-2 would have been developed. While Kenzo’s book is not specifically about the SR-2 or SLRs in general, it does shed some light on what was going on at the time.

Since the book is written entirely in Japanese and I do not speak or read it, what follows is my best attempt at a Japanese to English translation of that book, plus some additional insight from Andrea Aprà based on research he has done.

The history of the Minolta SR-2 is heavily rooted in the development of an earlier premium rangefinder camera, and likely shares some development between the two. This is similar to what happened at Nippon Kogaku in which the Nikon SP rangefinder and eventual Nikon F SLR were being developed at the same time, even sharing some parts.

It is likely true that for both Nippon Kogaku and Chiyoda Kogaku, the release of the Leica M3 stepped up the development of cameras for both companies. Chiyoda had just released the Minolta 35 Model II in 1953 when the new M3 escalated what a premium rangefinder could be. For Nippon Kogaku, the company was deep in developing what would become the Nikon S2, and the release of the M3 postponed that camera as new features such as a film advance lever and rewind knob were added last minute to improve the specifications in the face of a world class camera like the M3.

I believe that the release of the Leica M3 escalated the desire by both Nippon Kogaku and Chiyoda Kogaku to build a world class “Leica killer”. If true, this lends some credit to the comment by John Neubauer and Robert Moeser that work on a new SLR started in 1953. It is my opinion that actual SLR work probably didn’t happen in 1953, but the seeds for what would become an SLR were laid then.

After the release of the Minolta 35 Model II in 1953, work started on an all new model with a fresh design and more advanced features. Most Minolta collectors probably know about a prototype camera called the Minolta Sky which is said to have been completed in 1957, but never put into production, and while the Sky is definitely part of this story, it is not the whole story.

For starters, had the camera been put into wide scale production, it probably wouldn’t have had the name Minolta Sky. The word “sky” is actually an acronym for Shashin Kikai Yarikake which loosely translates to “photographic instrument in progress”, which is a fancy way of saying it was a prototype. The actual name of the camera probably would have been the Minolta 35 Model III, keeping it inline with the previous Model II that had come out in 1953.

According to Kamio Kenzo’s book, the head of development for the Minolta Sky was a quiet but stubborn engineer named Manzo Sugiyama who worked closely with Chiyoda Kogaku Founder and then current President, Kazuo Tashima. It is believed that Tashima was enthusiastic about his company’s new premium rangefinder and likely was involved in at least some of the decision making process.

Kenzo says that in 1956 Sugiyama and another engineer named Eiichi Furukawa developed a new type of focal plane shutter for the camera. Although specifications were not given, based on what is known about the Sky, this shutter likely had cloth curtains and had a range of speeds from 1 second to 1/1000 just like the Leica M3.

Around this same time, Chiyoda Kogaku had been in talks with Ernst Leitz of Wetzlar to license the Leica M-mount for use in their own camera. It is not clear exactly how far this discussion went or what Chiyoda Kogaku would have offered in exchange had the deal been made, but it hints at future negotiations in the early 1970s which resulted in the Leica/Minolta CL rangefinders and shared development of Minolta and Leitz SLRs. There are rumors that suggest Tashima might have wanted to use the Leica M-mount on his new premium rangefinder, but negotiations fell through, resulting in the creation of an all new bayonet mount, which Jim McKeown speculates would have been called the Minolta M-mount.

The Minolta Sky prototype was completed in early 1957 and Kenzo says that Kazuo Tashima was very proud of the camera and decided that he would handle the public relations for the camera himself. According to Kenzo, prior to boarding a plane to the United States where he intended to show off his new camera, he said, “If the plane were to fall into the ocean, I would hold this camera above my head with both hands.”

When he arrived in the United States, Tashima met with Lawrence R. Fink, an American businessman in charge of Minolta distribution in the US. Tashima reportedly had a great deal of faith in Fink and trusted his opinions on Minolta’s success in America. In his meeting with Fink however, things did not go as planned.

One problem that Tashima hadn’t envisioned was that the preferences of the US market were not the same as in Japan. In order to sell the Minolta Sky in the United States and still be profitable, the camera would have had to carry a retail price around $399.50. Although cheaper than the Leica M3 at $447, it was higher than Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon S2 at $345.

A second, and perhaps larger problem was that American photographers were giving up on rangefinder cameras faster than in Japan. While the Leica M3 and Nikon S2 were solid sellers, they only catered to a small percentage of the photographic market, and as each year went by, that market was shrinking. To introduce an all new premium rangefinder camera with a price in between the two most expensive options would have likely been a tough sell.

Realizing that no matter how good the new Minolta rangefinder might be, that it would likely be a slow seller in the highly desirable American market, Tashima made a swift decision to cancel production of the camera and instead focus on a new single lens reflex camera. Within days of returning to Japan, a new SLR development team was formed, using most of the same guys as the Minolta Sky.

While researching this article, I learned of another premium Minolta rangefinder called the Minolta 35 Model III which is not mentioned at all in Kamio Kenzo’s book. Unlike the Minolta Sky prototype whose name doesn’t actually appear anywhere on the camera itself, the Minolta 35 Model III is engraved as such and appears to be a later variant of the Minolta Sky.

This version of the camera uses a regular 39mm Leica Thread Mount instead of the bayonet of the Minolta Sky. What is not clear is where in the development timeline did the Minolta 35 Model III appear. Looking at the only two images of the camera known below, not only does the camera have the name of the camera engraved into the body, the rangefinder window is rectangular instead of round, a design element that would suggest a later production date. Whether or not this is true is just my guess, but I suppose that it is plausible Chiyoda Kogaku put in motion a plan to release a lower cost version of the nearly complete Minolta Sky with a simpler lens mount and perhaps omission of some other features, but at a lower cost to perhaps recoup some of the development cost.

I believe the Minolta 35 Model III prototype shown above came after the more often seen Minolta Sky prototype because not only does it look more like a completed camera, but the change to a rectangular rangefinder window would have been more consistent with a contemporary rangefinder from 1957-58. It is strange however, that at least 2 versions of the Minolta Sky prototype are known to exist, one on display at the JCII Museum, yet no known versions of the Minolta 35 Model III are known to exist. As is the case with most prototypes, what survives is hit or miss, and perhaps all evidence of the screw mount cameras were destroyed.

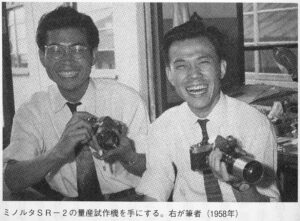

Getting back to the SLR, prototype versions of the as yet unnamed Minolta camera appeared in late 1957 and early 1958. This timeline is almost impossible to believe as Kamio Kenzo says in his book that Chiyoda Kogaku was able to create an all new SLR prototype in about seven months when most SLRs from other companies took between two to three years. In order to accomplish this feat, there certainly had to have been shared parts between the rangefinder and SLR prototypes. The most complicated part of any camera is the shutter, which likely was reused, along with the film compartment. If the engineers used as many shared parts as possible, that would have meant that only the pentaprism, mirror box, lens mount (which looks awfully like a reversed copy of the mount used on the Sky prototype), and top plate would have needed to be created from scratch.

In the image to the left from May 1958, two SLR prototypes are shown with a couple lenses, hoods, and a right angle viewfinder. At least one of the men in the image to the left is Kamio Kenzo so perhaps Manzo Sugiyama is there as well as the team who developed the SR-2 was said to be nearly the same as the one who created the Sky. Whoever they are, this image is thought to be taken at Chiyoda Kogaku’s Sakai factory.

The image quality of the prototype is very poor, so it is difficult to see, but the camera strongly resembles the finished SR-2 suggesting this was a nearly complete prototype. I don’t see the “Minolta” engraving above the prism, and the self-timer lever looks different but otherwise is very similar. The camera in the middle looks like it might have something on the front face of the top plate, above the self-timer where the exposure meter clip on the SR-3 is located.

Although we don’t have a lot of information regarding the development of the SR-2, it is clear that Chiyoda Kogaku was paying attention to what other companies were doing. Upon its release, the SR-2 was lauded for its clean design and modern feature set. It is easy today to look back at so many early SLRs and dismiss the SR-2s feature set as “run of the mill” but upon its release in October 1958, there wasn’t another camera like it.

The era in which the SR-2 was designed was extremely competitive and nearly every manufacturer was ready to release their new models months, sometimes even weeks after someone else. Canon and Nikon both announced their first SLRs a mere 2 weeks from each other!

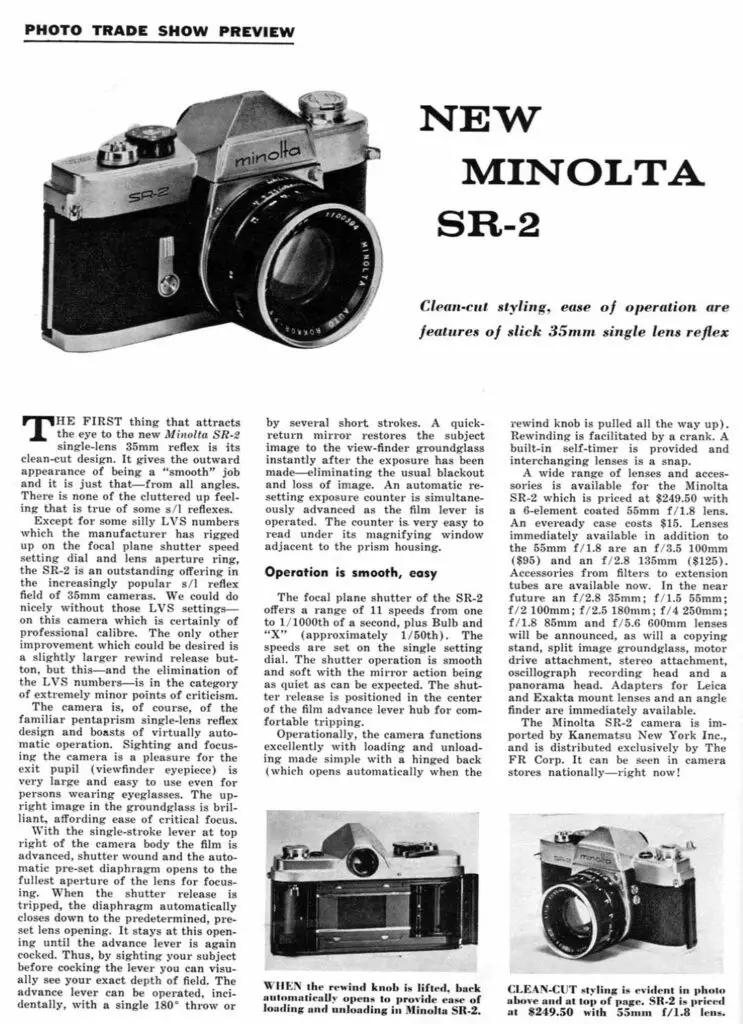

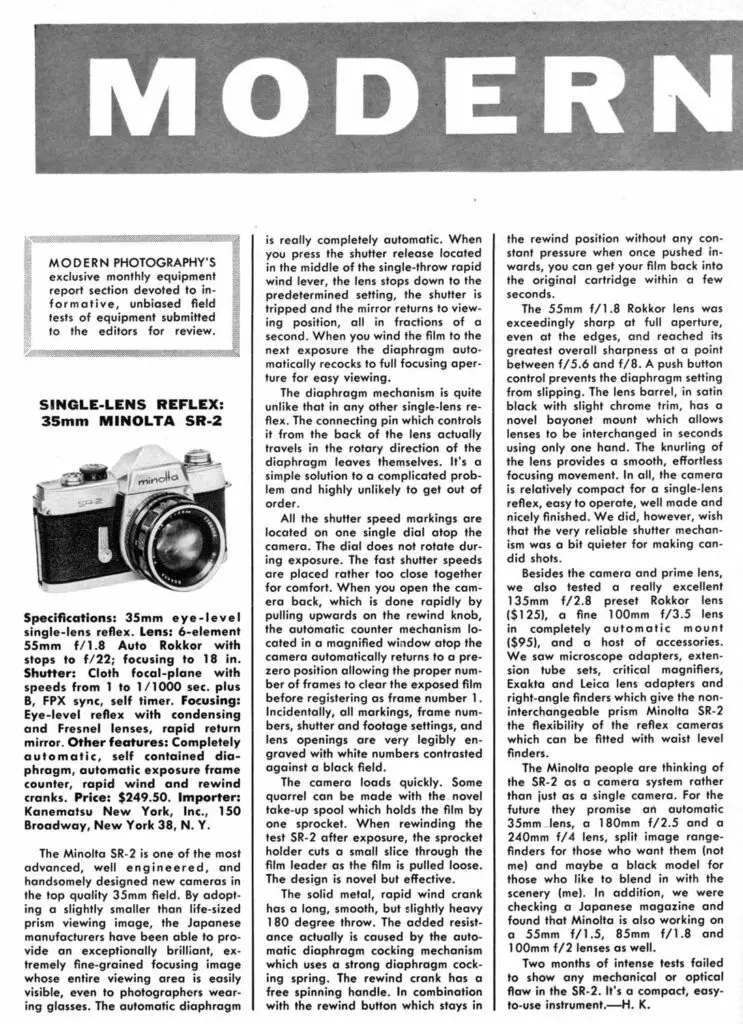

Below are two short previews of the Minolta SR-2 from the May 1959 issues of Modern Photography and US Camera. In the article, the SR-2 impresses the author with a great deal of positive comments about the camera’s features and performance. Cons are listed for the unorthodox LVS system and a small rewind release button, but nothing of significance.

Although the SR-2 was a great looking and performing camera with a combination of features not found in many other cameras, it sold poorly, with less than 20,000 thought to be made. We have the benefit of hindsight today to see two reasons for this. The first was the camera’s price. When packaged with the 55mm f/1.8 Auto Rokkor-PF, the camera had a retail price of $249.50, which when adjusted for inflation compares to $2640 today, a huge amount for a new style of camera made by a company with no prior experience.

A second, and certainly more problematic reason was that upon the camera’s release, only three lenses were initially available, the 55mm f/1.8, but also a 100mm f/3.5 and a 135mm f/2.8 and of those three, only the 55mm and 100mm supported an automatic diaphragm, the 135mm was a preset only lens. In time, more lenses would become available ranging from a 35mm f/2.8 to a monster 600mm f/5.6. A lack of an established lens system was not unique to the Minolta, as Canon only had 3 lenses available for the release of it’s first Canonflex, a camera which also failed to catch on with the public.

While Chiyoda Kogaku did eventually make more lenses available, to help offer a more affordable SLR option, a year after the SR-2s release came a discount model called the SR-1 which reduced the top shutter speed from 1/1000 to 1/500, and changed the kit lens to a 50mm f/2 Auto-Rokkor. These two changes allowed the camera to carry a retail price of $179.50 making it much more attractive.

Not wanting to give up on the promise of a well featured SLR, in 1960, a third model, called the SR-3 would make its debut which added a bracket for an optional clip on exposure meter that would couple with the camera’s shutter speed dial offering exposure metering to the camera’s robust feature set.

Despite immense competition and slow sales, Chiyoda Kogaku’s introduction to the world of 35mm SLRs would eventually catch on with models like the SR-7 in 1963 which was the first 35mm SLR with a body mounted coupled CdS exposure meter, and the SR-T 101 in 1966 which added through the lens metering via dual CdS cells in the camera’s body.

Minolta would continue to produce the Minolta SRT series until 1981 and would continue using the SR bayonet mount through the Minolta X-370s from 1995, giving the lens mount a respectable 37 year run before being replaced by the Minolta A or Alpha mount used on it’s Maxxum series of auto focus cameras.

Today, there is no shortage of collectible Minolta SLRs. Helping matters is that no matter which SLR body you use, if you mount one of many Rokkor lenses to them, you’ll have an extremely capable camera, whether you are using an entry level Minolta XG7 or a top of the line Minolta XK. Most of the earlier SR-mount cameras fly under the radar of collectors except the SR-2 due to its rarity and historical significance.

If you are looking to add an SR-2 to your collection, expect to pay in the hundreds of dollars for an average condition body and far more in excellent condition with a lens. If you just want to try an early Minolta SLR but don’t want to pay a premium, the Minolta SR-3 is a much more affordable option and is basically the same with the exception of the clip on meter. As with all Minolta SLRs, these are great cameras that were built with a high quality standard, and assuming they have not been abused over the years, should still perform well today.

My Thoughts

I actually thought I was done reviewing Minolta SLRs. I’ve looked at historic models like the SR-7, models from the 1970s like the XE-7, XG7, and XD11, and some electronic models like the X-570 and X-700, I’ve even reviewed the first fully integrated autofocus SLR, the Maxxum 7000.

Then one day while I was working on a review for the Olympus FTL, that company’s first full frame 35mm SLR, I got to thinking about other first SLRs by other companies. I had looked at the Nikon F, the Canonflex, and even the first Pentax, but I had never reviewed Minolta’s first SLR, so I got to hunting. Thankfully, the hunt didn’t take too long as I had come across Kristen Loretta who herself came across a huge stash of cameras in a storage locker owned by her boss. Whoever that collection previously belonged to, clearly liked Minolta as she had nearly every Minolta model ever made, with many duplicates. I arranged a nice SR-2 to be sent my way and I got to working on this review.

An observation I had when first handling the Minolta SR-2 which was similar to one I had with the Asahi Pentax AP and K models, is that the SR-2 seems to have a higher build quality than later models, even the SR-7 which came only four years later. That’s not to say that later Minolta SLRs are cheaply made, as they aren’t, but there seems to be an extra level of…something with Minolta’s first SLR. The best way I can describe it is like comparing a hand built German rangefinder vs a mass produced Japanese model. Both are very good, and built to a quality standard unheard of today, but there’s just something extra about some models that is hard to explain.

The camera has a reassuring solid feel, neither too heavy, nor too light, the chrome plating is extremely high quality and somehow feels “deeper” than other chrome plated cameras, despite being over 60 years old, the movement of the wind lever, the clicks of the aperture ring on the lens, and the action of the shutter as it fires are all smooth and without grit. It it clear that Minolta cared very much about the success of this camera and did everything they could to make it as good as possible.

Up top, the SR-2 doesn’t exactly hint at a first attempt 35mm SLR. Chiyoda Kogaku clearly paid attention to what other companies were doing and what the trends were for 35mm SLR style as the controls are all logically laid out without any ergonomic quirks often seen on earlier SLRs. On the left is a pretty normal looking rewind knob with fold out handle. I’ve seen some documentation that suggests the SR-2 was the first 35mm camera in which the film compartment is opened by tugging up on the rewind knob, instead of using a lock on the side of bottom of the camera. Next is the automatic resetting exposure counter, which is easy to read under a convex piece of glass.

To the right of the fixed prism is the shutter speed dial which is a two piece design in which the center does not rotate with the dial. Unlike other cameras of the era with two piece dials, there is no need to lift up on the dial to change speed, simply rotate it to whichever speed you need. Speeds from 1 to 1/1000 plus Bulb and an orange “X” sync setting are engraved. You may rotate the dial a complete 360 degrees in either direction as there is no “wall” after the 1000 setting. One interesting feature of the SR-2 is a LV numbering system on the lower edge of the shutter speed dial, which I will explain later. Next is the film advance lever with cable threaded shutter release button in the axial center. The film advance requires about an 180 degree motion to completely wind the camera, but is also geared to allow for several shorter strokes if you wish. Finally, on the far right is an engraved Chiyoda Kogaku logo. The Minolta SR-2 ended production before the company officially changed it’s name to Minolta.

The base of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket centrally located right under the mirror box which helps maintain balance while the camera is mounted to a tripod. To the side is a rewind release button, and on the opposite side is a black hole which was intended for a motor drive attachment that Minolta had planned for, but never released. Unlike traditional motor drives which advance the film and cock the shutter through gearing on the base of the camera, Minolta’s solution was external and would somehow manipulate the advance lever directly. The story goes is that once Nippon Kogaku released a motor drive for the Nikon F, Chiyoda realized that their solution was inferior, so the accessory was scrapped. The Minolta SR-3 has this same black recess as well.

The sides of the Minolta SR-2 are symmetrical with forward facing strap lugs. Locating the lugs in this manner helps to balance the camera when hanging from your neck with a lens attached, preventing it from falling forward. Also on the left side of the mirror box are two flash sync ports, one for FP and one for X. The Minolta SR-2 only came with a removable accessory shoe, which attaches to a ring around the rear eyepiece.

The back of the camera has a round film reminder dial in the center of the door. Black and white film speeds from ASA/DIN 10/11 to 1600/33 and color speeds from ASA/DIN 10/11 to 200/24 are available. A ring around the circular eyepiece can be removed to reveal a threaded ring for attaching viewfinder accessories. A nice cosmetic touch that exists around the entire top of the camera is a molded edge giving a top plate a stepped appearance. It provides no functional benefit, but definitely adds some style to a genre of camera that would increasingly become less visually interesting in the next decade.

Lifting up on the rewind knob on the top of the camera opens the right hinged film door to reveal a very modern film compartment. The cloth shutter curtains on this model are still in great shape without any cracks, tears, or pinholes, suggesting that whatever material was used, has held up very well. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed take up spool. The film leader attaches to a metal clip screwed into the take up spool. As there is only one connection point, you may need to manually rotate the spool to locate the clip. The take up spool rotates clockwise, wrapping the film in the opposite direction of how it was spooled in the cassette. The film pressure plate is a large rectangular metal plate with metal divots to help reduce friction as film passes over it. The SR-2 has no light seals on the door hinge or in the channels above and below the film gate. This is unusual for a camera of this era as most used yarn or felt seals. Deep channels instead protect light from leaking into the film compartment, which makes me wonder why more cameras from the 1960s and 70s couldn’t have done it this way?

With the introduction of the Minolta SR-2, Chiyoda Kogaku released a new series of SLR lenses in the SR-bayonet mount. The SR mount was used by all subsequent Minolta SLRs up until the release of the auto focus Maxxum 7000 which switched to a new Alpha mount. While most SR-mount lenses released from 1958 until the 1980s can be mounted to the SR-2, the original lenses do have some subtle differences from later SR lenses.

The most obvious difference between an original lens like the one mounted to this Minolta SR-2 is the locking aperture ring with LV value numbers engraved into the ring. The SR-2 uses a clever LV system that is similar to one I discussed in my review for the Minolta Autocord which was also released in 1958, the same year as the SR-2.

The Minolta implementation of the LV system uses two sets of numbers, one of the aperture ring and the second on the shutter speed ring which give you half of the total light value number for any given exposure. This system relies on an external light meter with LV numbers on it. With a properly calibrated meter, when exposed to a given amount of light, the meter will give you a LV number from 2 to about 17 which is transferred to the camera. Unlike other makers who simply had a single scale of LV numbers somewhere on the shutter, with the SR-2, you take the LV number given by the meter, and look at the LV numbers on both the aperture and shutter speed rings, and any combination of numbers that add up to the LV number on the meter, will result in proper exposure.

For example, lets say a meter gives you a LV of 13. Looking at the SR-2, the shutter speed setting for 1/125 has an LV number of 7 on the side of the dial. In order to get to 13, you need to choose an f/stop with an LV number of the difference, which in this case would be 6. On the aperture ring of the lens, LV 6 is the same as f/8. So with the camera and lens set to 1/125 and f/8, the two LV numbers add up to 13, which is what the meter is telling you, and you’ll get proper exposure. Lets say you needed an EV of 10. With the shutter still at 1/125, you need to move the aperture ring to LV 3, which is f/2.8. For someone who has never seen this type of metering system, it certainly sounds strange and I can imagine the thought of having to do math to calculate exposure doesn’t sound fun, but in use, it actually works pretty well. In fact, as someone who so regularly trashes the coupled EV systems found on so many 1950s and 60s cameras, I actually prefer this method of those used by other companies who employ various methods to physically link shutter speed and f/stops together.

As for the rest of the lens, another change is that the aperture ring has a lock, which prevents accidental changes to the selected f/stop. To some, this might seem strange as most SLR lenses let you freely change f/stops, but in order to do it here, you must press and hold a small button in the side of the lens, in easy reach of the fingertips on your left hand, while holding the camera. The rest of the Rokkor lens works as expected, with a metal focus ring with focus distances in both feet and meters near the front, and a fixed depth of field scale in the middle.

Up front, the Minolta SR bayonet uses a small metal lock near the 1 o’clock position around the lens to unlock the lens. Press and hold this lock while rotating the lens counterclockwise and the lens is removed, line up a red dot on the lens with a red dot on the lens mount while rotating the lens clockwise to reattach it.

To the left of the lens mount on the front body of the camera is a mechanical self-timer lever, which when activated counts down an approximate 10 second delay before firing the shutter. With the self-timer activated, a small button behind it is used to begin the countdown. Pressing the normal shutter release button with the self-timer activated will not begin the countdown. You can continue using the camera with normal shutter operation using the top plate shutter release, even though the self-timer is activated. If you wish to cancel the self-timer after it is activated without firing the shutter, fire the shutter as normal using the top plate shutter release, and then press the self-timer button to begin the countdown, but without firing the shutter at its conclusion.

The Minolta SR-2’s viewfinder is quite bright and is easy to use, especially for one from 1958. A noticeable Fresnel pattern radiates from both a split image focus aide and ground glass circle in the center. This Fresnel pattern helps distribute light across the focusing screen, minimizing darkness near the corners like on other mid century SLRs. Considering one of the biggest cons to using early SLRs were dim viewfinders, seeing the brightness of the Minolta was likely a game changer for many people. No other information is seen in the viewfinder such as exposure information.

As I describe the features and controls of the Minolta SR-2 in this review, I have to constantly remind myself that I am using a 65 year old camera. To describe the SR-2 as a fairly normal SLR with good ergonomics and familiar controls misses how pioneering the camera was. To have made it to market before several major competitors with a design that so closely mimics SLRs from decades later is truly one of the SR-2’s greatest accomplishments.

Of course, I can sit here all day typing about how “normal” the camera feels, but how does it perform? Load in some film and show us some results, you’re probably thinking and if you are, you’re in luck, so keep reading…

My Results

A quick note about the sample results below. I had wanted to review the Minolta SR-2 for quite some time, but they’re pretty hard to find in good working order for a reasonable price, so after a couple years of searching, I “settled” on an excellent and perfectly working Minolta SR-3 as its pretty much the same camera, only with support for the optional clip-on meter.

I loaded in a fresh roll of Fuji 200 into the camera and shortly after finishing that roll, I came across a really nice SR-2 body. Since I still wanted to review the SR-2 for it’s historical significance as Minolta’s first SLR, I mounted the lens from the SR-3 to the SR-2 and shot a roll of Ferrania P30.

The images from both rolls are included below. Even though I did use an SR-2 for the black and white photos and an SR-3 for the color ones, I used the exact same lens on both and the user experience between the two is identical so everything I have to say about the SR-2 also applies to the SR-3.

Although I had high expectations for the results from the SR-2, I had no idea of the accuracy of it’s shutter, or how this early SR-mount lens would perform. It is worth noting to eagle-eyed Minolta collectors that this lens, with serial number 14xxxxx is actually a slightly later lens from about 1960 and would have originally been mounted to an SR-3, not the SR-2, but the lenses are 100% compatible and had I not typed that, a majority of people reading this would have never know.

So, whether this is an SR-2 or SR-3 era lens, the 7-element Rokkor-PF performed as great as I had expected. Images were nice and sharp across the image with no vignetting or softness near the edges, contrast was excellent, as was color rendition on the Fuji 200. I have always held Minolta’s Rokkor lenses in high regard and I was pleased to see this early lens performed as good as the later Minolta SLR lenses that I was more used to. I believe that this lens could have been mounted on a Minolta X-700 and delivered just as good of results (although with less automation).

I found the viewfinder to be very bright and easy to use, especially for a camera from 1965. I would suspect that first time users of the Minolta SR-2 would have been very impressed, especially considering dim viewfinders were one of the many “cons” to using earlier SLRs.

Perhaps the most striking characteristic of using the SR-2 was in how much Minolta got right with their very first SLR. If I was a new collector, you could have shown me this camera and a late 1970s SRT and I would have no idea that the two cameras were two decades apart. Minolta did an impressive job with their first attempt at an SLR. The ergonomics and locaiton of the camera’s controls feel no different than SLRs from decades later. The camera has incredible balance and by the time I got done taking the first exposure on my first roll of film, I already felt a sense of familiarity with it.

In fact, the only two things that I didn’t like are incredibly minor, which was the locking tab on the aperture ring and the use of the LV scale, which is hardly an issue as you can just ignore it. Unlocking the aperture ring isn’t difficult to do, but with the camera to your eye, if you plan on adjusting the aperture, it often took me a second for my finger to locate the button. Again, its a very minor issue, and if it bothered me enough, I could just mount any number of later SR-mount lenses to the camera which don’t have that lock.

Beyond that though, the Minolta SR-2 is a homerun, a rare example of a company who did their homework, included the features most useful to their target customer, and designed a camera that is very easy and fun to use. In fact, I am really surprised this camera didn’t sell better as I see no reason for anyone to not buy it, when cameras like the Nikon F and Canonflex were more expensive.

Most anyone making it this far into this article already knows that Minolta would play a significant role in the camera industry over the next several decades. The Minolta SR-2 was only produced for a very short period of time, but its impact is undeniable. If you are a Minolta completist, or just like historically significant cameras, including one in your collection is a no brainer. If by chance, you come across one for a reasonable price, and all you care about is shooting it, then by all means go for it. It is a great camera that in working condition is just as capable as many of the company’s later models.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_SR-2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minolta_SR-2

https://www.cameraquest.com/minsr2.htm

https://www.rokkorfiles.com/SR%20Series.htm

https://earthsunfilm.com/vmlp-3-the-minolta-sr-2-the-start-of-something-big/

Excellent Article and photos from the Minolta SR2. I use to own a Minolta SR1 and love it!!!

I literally just purchased an SR-3. Though dirty from age, it works perfectly. I’m impressed with the quality and fit. And just like the Pentax H3v I recently bought, the early examples of these SLR giants are dare I say “better” than their offspring?

Mike, very nice piece! The background information was very well done, and i know it was hard to dig up because I tried. Interestingly, your SR-2 has a split-image focus aid. Mine (I have two) do not and have SN# starting 111… Your copy seems to be later. My SR-3 has the split-image aid though. It’s curious that my SR-T 101 does not.

Strangely enough, for some reason the physical “look” of the lenses seems to remind me of the Mamiya SLR lenses of a slightly later era…were they sourced from the same manufacturer? 70’s era lenses were certainly very good and had a reputation. Did they start by sourcing lenses until they could build their own?