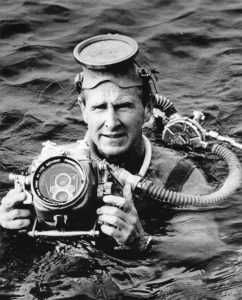

This is a Nikonos II, an amphibious 35mm camera produced by Nippon Kogaku between 1968 and 1976 for underwater photography. The Nikonos series was originally designed by a company called La Spirotechnique in France in 1960, and sold as the Calypso-Phot. The Calypso was conceived by Jacques Cousteau and was a “system” camera for underwater exploration, featuring interchangeable lenses, accessory flashes, and other accessories. The French company, ATOMS that was producing the camera did not have the necessary experience to build the camera, so they approached Nippon Kogaku to help them create the camera, and granted them distribution rights outside of France and some European countries. By 1963, Nippon Kogaku was the sole distributor for the Nikonos worldwide. The Nikonos series was hugely popular, spawning several later versions which remained in production until 2001.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 35mm f/2.5 W-Nikkor coated 7-elements

Lens Mount: Nikonos Bayonet

Focus: 2.75 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 35mm Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/30 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and FP, M and 1/60 second X Flash Sync

Weight: 701 grams (w/ lens), 531 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikonos_ii.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Nikonos II was Nippon Kogaku’s update to the original Nikonos, which itself was their version of the French produced Calypso camera. Using a very clever design purpose built for underwater photography, the Nikonos II is a very capable camera both above and below water. The base W-Nikkor 35mm f/2.5 lens is optically the same as the 35mm f/2.5 Nikon rangefinder lens and performs just as well above ground, but can be had at a fraction of the price. Even if you have no interest in underwater photography, the Nikonos system might be just what you’re looking for! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for significant historical significance as the first fully complete underwater 35mm system camera | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.2 | ||||||

History

Throughout the history of photography, many attempts at building a camera capable of underwater photography have been made. The first known underwater photographs were taken in 1856 by William Thompson using a camera mounted to a pole. Later underwater cameras were nothing more than water tight enclosures containing a box camera sealed with wax.

As photography advanced throughout the 20th century, so did underwater photography with the first underwater motion picture in 1914 and the first use of flash in 1926. In 1954 Franke & Heidecke built a water proof enclosure for the Rolleiflex TLR called the Rolleimarin for famous underwater photographer Hans Hass. Although suitable for depths as far as 100 meters, the Rolleimarin wasn’t actually a camera, rather just a housing that the Rolleiflex went inside of.

Until then, all options for making underwater photographs were large and clunky, usually requiring an above water camera to be installed inside of something else, but in 1956, French Naval explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau created a wish list of sorts of what he wanted to see in an all inclusive underwater camera system that didn’t require any external housings, and could take high quality images using 35mm film.

In 1956, a French company specializing in manufacturing underwater equipment called La Spirotechnique commissioned Belgian inventor Jean Guy Marie Josef de Wouters d’Oplinter to create a compact and self contained camera that met all of Costeau’s requirements. Costeau and La Spirotechnique had previously worked together, developing an underwater breathing apparatus called the Aqua Lung, among other things.

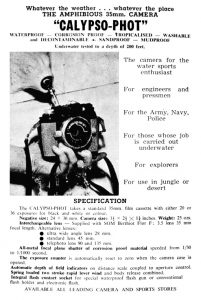

The next year, a prototype camera, now called the Calypso-Phot, named after Costeau’s famous research ship, RV Calypso was revealed. The new camera had a very innovative and unconventional design. A great deal of thought was put into the tactile controls of the camera like the shutter release, focus, and aperture wheels so that they could be easily used underwater with gloves.

The camera shutter and film compartment was part of a main body that was inserted into an outer shell, outlined by thick water tight seals. The lens mount used the same kind of seal, but connected directly to the body itself, rather than the shell for the tightest possible fit. To eliminate any chance that water could leech through the metal casting, all surfaces of the body and shell were anodized and heat treated with resin.

The base lens for the camera was a SOM Berthiot Flor 35mm f/3.5 lens with four accessory lenses ranging from 28mm to 135mm. The shutter was unlike any other developed for any camera, featuring a vertically traveling metal blade made of something called Duralumin that could resist corrosion due to moisture in the air when the camera was being loaded or lenses changed. The shutter was capable of speeds from 1/30 all the way to 1/1000 which matched that of the highest precision above water cameras.

When it was ready for production in 1960, La Spirotechnique outsourced production to another French company called ATOMS (Association de Techniciens en Optique et Mécanique Scientifique), who had experience making shutters and cameras both under their own name and for other companies.

Despite being the world’s only complete 35mm solution for underwater photography, and being connected to Jacques Costeau, the Calypso-Phot only sold modestly well. No production numbers have been kept, but estimates of anywhere between 4000-8000 were thought to have been made.

If you research the history of the Calypso camera online, nearly every site will say something like in the years after the camera was first released, Nippon Kogaku was offered a contract to build their own version of the camera, but how this actually happened and why is a mystery. Even Nikon’s present day history site suggests that the answer is not entirely clear.

The most common (and logical) explanation is that La Spirotechnique was not an optics company and reached out to Nippon Kogaku for their expertise in building the lenses and shutters to be able to sell the camera at a reasonable cost. Could Nippon Kogaku have been building the bodies the entire time, or did La Spirotechnique originally handle production themselves but eventually reached out to Nippon Kogaku when demand got too high?

Around the time of the Calypso’s development, Nippon Kogaku had created an underwater housing for their Nikon rangefinder called the Nikon Marine. The Nikon Marine was produced in very low numbers, but like the Rolleimarin was just a housing, and not an actual camera. Perhaps Nippon Kogaku had wanted an underwater camera of their own and saw the Calypso as a better option.

We may never know the full story as to how Nippon Kogaku first became involved, but what we do know is that in 1962, the Nikonos was released as a near identical copy to the original Calypso. The two most obvious changes were a switch to Nikkor lenses, rather than the original SOM Berthiot lenses, and the absence of the top 1/1000 shutter speed. Depending on the market the camera was sold in, some were co-branded as a Calypso/Nikonos, and others it was just the Nikonos.

We may never know the full story as to how Nippon Kogaku first became involved, but what we do know is that in 1962, the Nikonos was released as a near identical copy to the original Calypso. The two most obvious changes were a switch to Nikkor lenses, rather than the original SOM Berthiot lenses, and the absence of the top 1/1000 shutter speed. Depending on the market the camera was sold in, some were co-branded as a Calypso/Nikonos, and others it was just the Nikonos.

The original Nikonos was on the market for 5 years, selling about 30,000 examples before an updated model, called the Nikonos II was released in 1968. With the Nikonos II, the overall design of the camera remained, with a new fold out rewind crank, an improved film pressure plate, and some cosmetic changes to the base 35mm f/2.5 lens that brought back the long white arrows pointing to the distance and aperture scale of the original Calypso lenses.

In the ad to the left from June 1970, the Nikonos II is listed with a 35mm f/2.5 lens for $195, which when adjusted for inflation compares to a little over $1300 today, quite a bargain, considering the specialized nature of the camera.

In 1975, the camera was revised once again, this time called the Nikonos III, changing the rewind crank, improving the viewfinder with projected bright lines showing both 35mm and 80mm focal lengths, and an improvement to the film transport, adding a sprocketed shaft to help maintain even film spacing. The Nikonos III would be the last of the first generation camera, built on a body created in France by Jean de Wouters. Starting in a 1980, the Nikonos IV-A would debut, featuring a completely new body entirely designed by Nippon Kogaku featuring TTL metering and an electronic shutter.

The Nikonos line would stay in production until 2001 as the world’s only complete 35mm underwater system camera. A huge number of accessories including closeup adapters, flashes, auxiliary viewfinders and other things were created for it. In 1992 a new Nikonos RS SLR would be created, making it the only underwater 35mm SLR.

Today, Nikonos cameras are still popular as they were built to such a high quality standard, and assuming the o-rings are in tact, still work as good as they always did. Although digital cameras have largely replaced film cameras as the underwater camera of choice, there’s something to be said about a fully mechanical camera to be used in the depths of the ocean, as opposed to something loaded with electronics, CPUs, and lithium-ion rechargeable batteries. Even if you have no intention of shooting them underwater, with the right lenses, they are also very capable above water cameras as well.

My Thoughts

During one of my many conversations with Nikon historian Bob Rotoloni, we were talking about Nikon rangefinder lenses and he made the passing comment that Nippon Kogaku used the same exact formula of the W-Nikkor 35mm f/2.5 rangefinder lens for the Nikonos underwater camera, and my ears perked up. Knowing that the rangefinder version sells for upwards of $350 by itself, and Nikonos II lenses often go unnoticed sometimes for as little as $5, I knew I had to have one. After a short search, I had my own Nikonos II and W-Nikkor lens on the way. I paid around $30 for the camera and lens, which wasn’t five bucks, but was still a heck of a deal.

Although I had seen pictures of many Nikonos cameras before, it wasn’t until I held one that I could truly appreciate it’s clever design. Jean de Wouters’s original design for the Calypso is still mostly in tact with the Nikonos II and what he managed to pull off is impressive. Since the release of the first Leica in the 1920s, there really haven’t been all that many 35mm cameras that were truly new from the ground up. Even many of the first SLRs like the KW Praktiflex, Asahiflex, and KMZ Zenit all used bodies that were loosely based off the Leica rangefinder.

With the Calypso, absolutely nothing was borrowed or even inspired by another camera. The shutter was a completely original design, unlike that of any which came before it, the lens mount was a two claw bayonet that didn’t resemble that of any other camera, and the control layout was extremely clever, optimizing underwater use while wearing bulky gloves. Even the strap lugs are noteworthy as they serve double duty as handles for opening the camera.

Up top, we see the fold out rewind knob new to the Nikonos II on the left side and accessory shoe in the middle, making these two of the only controls on the camera that are in the same location as other 35mm cameras. The shutter speed dial on the right is large and easy to grip with gloves and also has very prominent click stops at each speed which likely help underwater. You’ll notice a red “R” on the shutter speed knob next to 500 which is used for rewinding the film at the end of the roll.

My overuse of the word “clever” in this review continues with the combined film advance and shutter release located in front of the shutter speed knob. When the shutter is not cocked, this lever sticks out over the front of the camera at an approximate 60 degree angle. An inward press of the lever towards the back of the camera both cocks the shutter and advances the film, readying it for the next exposure. A second inward press of this lever fires the shutter at whatever speed you’ve selected and upon removing your finger, returns back to the original 60 degree angle.

To prevent accidental exposures while the shutter is cocked, there is a pivoting guard in front of the accessory shoe that can be placed in a position which prevents pushing the shutter release. Although a necessary feature of the camera, it must be completely out of the way when advancing the film as it will prevent the shutter from being cocked, causing frame spacing issues.

The bottom of the camera has a 1/4″ tripod socket with coin-sized notches on it’s edge allowing you to unscrew it to reveal a flash sync port for Nikonos specific flashes. In the center is a clear window for viewing the internal exposure counter which is actually part of the internal shutter mechanism. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many shots have been taken and automatically resets back to 0 when the camera is opened.

The Nikonos has a rather symmetrical body, so each side looks the same as the other, with the only noticeable difference being in the color of the knob sticking out of the lens.

By far, the most significant feature of the sides of the camera are in the strap lugs, which to someone not familiar with how the Nikonos works, might think they look like dangling earrings.

The water tight design of the Nikonos is achieved largely by a two piece design in which the shutter and film compartment are all contained within an outer shell. The two pieces are cleverly locked together by the lens mount, which is actually on the inner part of the camera. With the lens removed, separating the two halves of the camera simply requires lifting the top half of the camera out of the shell. A thick rubber o-ring keeps things water tight and simply pulling the two halves of the camera is very difficult, so to help, these “dangly earrings” serve double duty to give you more leverage when opening the camera.

In the previous image, you can see the strap lug lined up with a little finger that when allows you to press down on the lug, lifting up on the top plate of the camera. It’s a bit hard to explain, but just look at the picture and imagine both sides being like that. Press down on the edge of the strap lug and the top comes off.

With the camera apart, the genius of the original Calypso design becomes even more evident. The shutter travels vertically and is a single piece of moisture resistant metal. Without curtains to the side of the film gate, the distance from supply to take up spool is very short, meaning you should more easily get an extra image or two on each roll using the leader and trailer of the film.

Film travels from left to right onto a single slotted and fixed take up spool. Before installing a new cassette, you must first fold down on a spring loaded circular plate which helps hold the film cassette into place. The film pressure plate is hinged at the top and folds up, so I found it easier to load film into the camera with the film compartment laying on a flat surface with the hinge facing you.

You’ll notice the lack of a sprocketed shaft like you’d see on most 35mm cameras. The lack of such a feature meant that frame spacing on the Nikonos II sometimes is uneven and can be negatively affected if the shutter lock gets in the way while advancing the film. This feature was added to the later Nikonos III in 1975.

Each lens for the Nikons has it’s own self contained aperture and focus distance scales. The focus distance scale is in both meters and feet and has a clever depth of field scale similar to that found on many German lenses by Zeiss or Schneider in which two red tipped arrows change positions depending on the f/stop selected. Wide open and the arrows are close together to indicate a narrow depth of field, but as you stop down the lens, they separate to indicate greater depth of field.

Looking at the front of the lens, the black knob on the left controls the aperture and the beige knob on the right controls focus distance. Both the black and beige knobs are actually just rubber covers over plain metal knobs which on many of these lenses have fallen off or rotted away. On this one, the black rubber has held up well, but the beige one is cracking in many places.

To remove the lens, simply rotate it 90 degrees either clockwise or counterclockwise and pull off. You must remove the lens before you can open the camera as the bayonet for the lens is actually on the inner part of the camera, not the outer shell.

Every Nikonos lens is sealed behind a large clear glass window which depending on which lens is used, restricts it’s use outside of the water. The 35mm W-Nikkor and 80mm Nikkors are the only two available that can be used both submerged underwater and in the air. The 15mm, 20mm, and 28mm UW-Nikkor lenses must only be used under water as the refraction properties of the front glass, combined with how light moves underwater changes causes undesirable artifacts when used in the air. One addition lens, called the LW-Nikkor 28mm is a “splash proof” lens which is designed primarily to be used in the air, but can withstand splashes for use at a beach, swimming pool, or other places where moisture is high, but is not rated to be submerged.

The viewfinder is a simple scale focus Albada type with projected frame lines for the 35mm lens with parallax has marks. The lack of a focus aide like a rangefinder is not much of an issue since all Nikonos lenses except the 80mm are wide angle designs with incredible depth of field. With the 35mm W-Nikkor lens at f/11 focused to about 12 feet, everything from about 6 feet to infinity is in focus. If you’re lucky enough to have the 15mm UW-Nikkor, you can achieve hyperfocal distance from 3 feet to infinity as wide as f/4, essentially making the Nikonos a focus free camera.

With the generosity of a 35mm focal length, using the Nikonos above water is incredibly easy. For anyone wishing they could shoot a wide angle Nikon rangefinder, but cannot afford a lens for one, using the Nikonos offers a very similar experience.

As the descriptions in this article likely prove, if you’ve never shot with a Nikonos before, it’s worthwhile to practice with it before loading film into the camera. While the controls were all thoughtfully designed for underwater use and are just as usable above water, there is no other camera like it, so you really don’t want to be fumbling around with it while you have film loaded into it. But once you do, the big question is, how does the camera perform, and more importantly, is the W-Nikkor 35mm lens REALLY as good as the one for the Nikon rangefinder?

My Results

Last winter, my friend and fellow blogger Alan Duncan had proposed an idea in a private chat we have with other bloggers to do a test to see how recent changes to TSA guidelines might affect film that has traveled through the air multiple times. Alan had an order of film that was sent internationally and never picked up by the buyer, and it was sent back to him. After completing two international trips, he sent a couple of rolls to me, making three cross-Atlantic trips and accumulating more air miles than I did in the last decade.

One of those rolls of film was Fuji Neopan 400 CN, a black and white film that is developed using C41 color chemistry. This style of C41 black and white film became very popular in the 90s and early 2000s as labs tried to downscale their development equipment so that they didn’t have to have separate chemicals for black and white. When shooting C41 black and white, they could just use the same process for everything.

I chose for that roll, the Nikonos II because, well, why not? After shooting that roll, I wanted to see how the Nikkor fared with color, so this past summer I loaded up a second roll of fresh Fuji 200. If you’re interested to see the results of Alan’s test with mine and several other rolls he sent out, check out his article here.

Although he already covered it pretty well in his article, I can confirm that there were no ill effects from the multiple international trips by the Neopan 400CN film took, nor on the other rolls he sent me.

Between both rolls of film, I am also happy to report that there’s nothing to see in these images that leads me to believe that the W-Nikkor 35mm f/2.5 isn’t a high quality rangefinder lens. Sharpness is perfect across the entire frame with no softness or vignetting near the corners. The images have a modern, almost digital look to them that is void of any optical anomalies seen in lesser lenses. The black and white images have what I consider to be a perfect balance of contrast, and the color images look digital-esque with no chromatic aberrations. This is simply a stunning lens.

If it’s not obvious this far into the review, the Nikonos is a very unique camera that was purpose built for underwater photography. Everything about it, from the lens mounted focus and aperture knobs, to the combined film advance lever and shutter advance are different from that of any other camera I’ve ever used.

Any time you change something from the expected norms, there’s a risk of a miserable shooting experience, and I can honestly say that despite the Nikonos’s many ergonomic differences, that I still really enjoyed shooting it. The hardest thing for me to get used to was the position of the shutter release, which requires my right arm to grip the camera from the top down. In the bathroom selfie image to the left, you can see how I typically held the camera. It wasn’t difficult or uncomfortable, just different.

With the incredible depth of field offered by the 35mm lens, in outdoor scenes, focusing was barely a thought for me. As long as I resisted closeups, I was able to shoot through a whole roll of film quickly as I didn’t need to ever think about focusing.

Underwater cameras like the Nikonos require the many rubber o-rings around the body, lens mount, and tripod socket to be perfectly water tight, and not knowing the history of this particular camera, I wasn’t willing to risk submerging the camera in deep water, but I did make an attempt to shoot a couple pics inside of a friend’s swimming pool at a depth of about 3-4 inches. I figured a quick dip in very shallow water shouldn’t hurt anything even with degraded o-rings.

Although no water leaked into the camera in my quick test, it is clear that there is a lot more to underwater photography than simply submerging the camera and pressing the shutter release. Of the four images I took, the one to the right is the best one and it’s not very good. Two important considerations of shooting any camera underwater is that due to how light travels through water compared to the air, your focal length actually changes. The 35mm lens mounted to this camera, becomes closer to a 45mm lens underwater meaning you’ll need a little more distance away from your subject, but also, as light doesn’t travel as easily underwater, you also need to compensate on exposure, which is something I did not do. In all four images, the framing was off, and my images were greatly underexposed.

The biggest issue I faced with this camera was that the sliding lock which is behind the shutter release for preventing accidental exposure, can sometimes get in the way while advancing the film, which will cause erratic frame spacing. This happened on both of my rolls, so is something you’ll want to be mindful of.

Despite my poor underwater results, my excitement for this camera was not at all affected. This is a camera I had always figured I would use above water, and if you consider it as a discount option to a Nikon rangefinder with a Nikkor 35mm lens, it was a roaring success. Nikon S2 bodies typically sell in the $300-$400 range in working order, and the rangefinder version of this lens can easily double that, so to buy the tandem together, you’re looking at nearly $700 to shoot what you can easily recreate here for sometimes less than $50.

Of course, a Nikonos II is not a Nikon S2, but considering the significant difference in price, you still get a really well built and cool camera, that’s fun to use, and makes outstanding images! It’s probably a good thing that the ultra-wide 15mm and 20mm UW-Nikkors are underwater only lenses, otherwise I’d be on the hunt for one of those too, which I am sure would get quite expensive!

Whether you are a collector, a user, or into underwater or above water photography, the Nikonos II, or any camera in the family is a worthy addition to have. This is a camera that checks all the right boxes for me, it’s got a cool history, is a well built and innovative camera that’s fun to use, offers a unique experience, like I keep saying, produces excellent images. Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikonos

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikonos_II

http://www.nicovandijk.net/nikonos.htm

https://casualphotophile.com/2018/04/17/nikon-nikonos-retrospective-review-film-camera-blog/

https://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-nikonos/index.htm

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/companies/nikon/htmls/models/htmls/nikonos13.htm

http://www.nikonosproject.com/how-do-i-use-this-camera/2014/9/2/the-nikonos-buyers-guide

An old Nikonos trick: when mounting the lens rotate it 180 degrees and then mount. The lens and camera don’t care if you do this. Now when the lens locks into place and you flip the camera up to check lens settings the numbers and focus arrows will be right side up…easier to read

I see from the color photograph of you holding the camera that you have a T shirt made in Italy. Showing similar immaculate taste, we have a leg lamp in the living room window.

Yes, I love that movie. Having grown up in Northwest Indiana, I can relate to the scenery (even if the movie wasn’t actually filmed in Hammond, they did a good job of replicating it). Plus I was Ralphie’s age the first time I saw that movie, so it perfectly captured what Christmas is like for a boy that age. I watch it every year at least once!

We both love that movie, so watch our DVD of it every year. We are older, so this is a reflection of our childhoods. My wife grew up a tomboy, so she relates to it just as much as me. Some friends gave us the leg lamp as a joke one Christmas. We put it in the living room window and never took it down. Anything from Fragile, Italy deserves a place of honor.