This is an Olympus FTL, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera produced by Olympus Optical Company of Japan in 1971. The FTL was Olympus’s first full frame 35mm SLR and was released a year before the Olympus OM-1. Unlike the later OM-series, the FTL uses a 42mm screw mount with a custom locking pin allowing for open aperture metering, a feature not commonly found on screw mount SLRs. Non Zuiko lenses can be used on the camera, however without the locking pin feature, only stop down metering is allowed. It has dual CdS exposure meters on either side of the eyepiece, a focal plane shutter, and a larger, more traditional body. The FTL was only produced for one year and was quickly discontinued upon the release of the Olympus OM-1 in 1972.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.4 Olympus G.Zuiko Auto-S coated 7-elements in 6-groups, 28mm f/3.5 Olympus G.Zuiko Auto-W coated 7-elements in 5-groups

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount w/ Olympus Auto Locking Pin

Focus: Variable, 1.35 feet / 0.4 meters to Infinity, 10 inches / 0.25 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism, 0.92x Magnification

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: 2x Coupled CdS Cell w/ TTL Metering and Viewfinder Match Needle

Battery: 1.35v PX625 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and FP and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, Battery Check

Weight: 898 grams (w/ 50/1.4 Lens), 848 grams (w/ 28/3.5 Lens), 645 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/olympus_pdf/olympus_ftl.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Olympus FTL was a short lived camera that at first glance, does not appear to be anything special, but upon further handling, is a well built and high quality 35mm SLR with an innovative metering system. Although a great number of camera makers produced lenses in the M42 mount, the screw mount Zuikos made for this camera are one of a kind and a good enough reason to pick up this camera. If you can find a working example of this camera with it’s original lenses, it’s a must have for any collector or shooter. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.0 | ||||||

History

The man most often credited for Olympus’s most famous cameras is Yoshihisa Maitani. It’s a story I’ve told on this site many times before, but the short of it was, in the late 1950s, as a junior employee, Maitani was tasked with creating a camera that would sell for under 6000 Yen. This was an ambitious task as at the time, the least expensive Olympus camera cost nearly four times that amount.

Cutting every possible corner, including shrinking the film size down to 18mm x 24mm and using as many plastic parts as possible while not sacrificing quality, in 1959, Maitani would present to the world the first Olympus Pen, officially kicking off the half-frame 35mm craze in Japan. Over the next decade many different Olympus Pen models would be produced, including an SLR called the Olympus Pen F, which Maitani also had a hand in designing.

In the years that would follow, Maitani would create a 35mm SLR called the Olympus M-1. The “M” stood for Maitani, but unfortunately the name was deemed too close to the Leica M-series so a year after it’s release, the name was changed to OM-1 and from that point on, launched the highly successful lineup of Olympus OM-series SLRs and lenses.

In the 1979, Maitani wowed the world once again with another compact camera, this time a full frame model with a clamshell body, a coupled rangefinder, and an excellent 6 element lens. This camera, the Olympus XA, would also lead to a series of popular Olympus XA compacts produced throughout the 1980s.

Yoshihisa Maitani was clearly talented, and his designs and ideas shaped Olympus for decades to come, allowing the brand to be highly successful in segments other companies didn’t touch. Although he would retire from Olympus in 1996 and pass away in 2009, Maitani’s influence can still be seen with Olympus digital cameras, such as their Pen Digital models which have styling clearly inspired by those original film cameras.

For as influential as Maitani was, this review has almost nothing to do with him. If you were to ask a bunch of collectors to name Olympus’s first full frame 35mm SLR, most people would likely choose the OM-1, but for those with a deep knowledge of the company’s history, you’d know that there was one model which came before the OM-1, the Olympus FTL.

To fully tell the story of this oddball Olympus SLR, we need to go back all the way to 1963 right before the Olympus Pen F half frame SLR was released. At the time, 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras were extremely popular. Nearly every Japanese camera maker was releasing their own designs. Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Konica, Yashica, Petri, Mamiya and others all had their own respective models, so it was likely an obvious decision to the management of Olympus that they should start on one too.

In a lecture given by Maitani at the JCII Camera Museum in Tokyo on Saturday, October 29, 2005, Maitani retells the story of how the original Pen and Pen F SLRs were conceived. He states that development of a full frame 35mm SLR had started in parallel with the half frame Pen F. Maitani himself was focused on the Pen F, and was not involved with the as yet unnamed camera, only saying that once it made it past the R&D stage, development clashed with the Pen F. As the half frame Olympus Pen series was a hot seller, it was determined that a half frame SLR would take priority and the full frame model was shelved.

As expected, the Olympus Pen F was released to great fanfare and the model proved to be very popular, eventually spawning a couple variants like the metered Olympus Pen FT model. Despite the success of the half frame SLR, the appetite for a full frame model only got stronger, and Maitani was eventually convinced to work on a new full frame 35mm SLR.

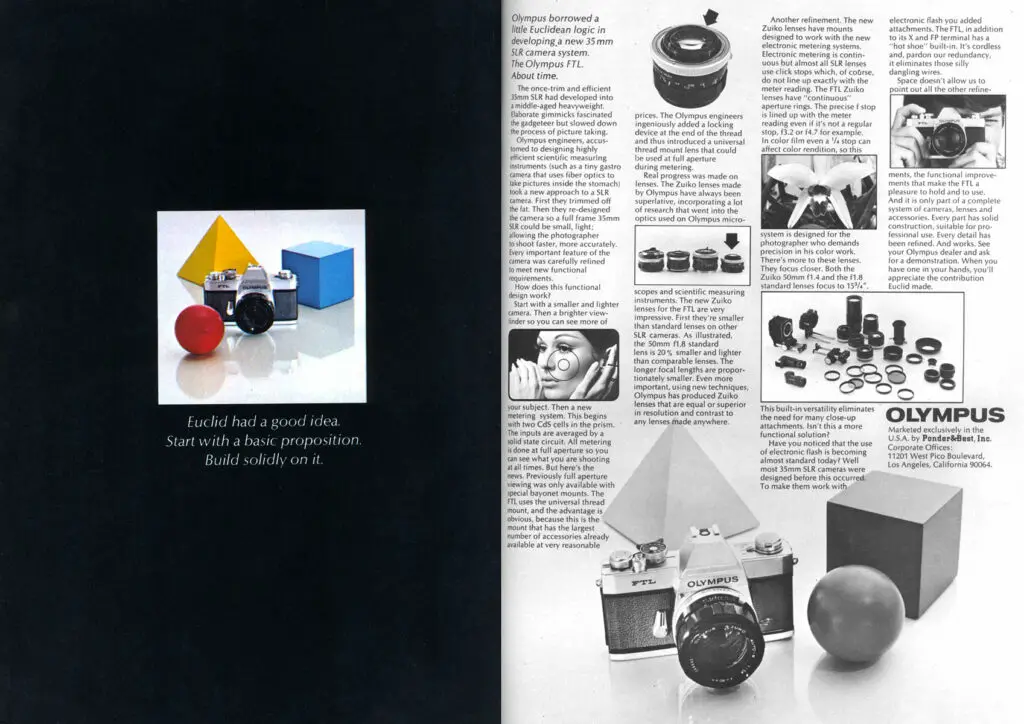

Yoshihisa Maitani recants that initially he was not interested in making an SLR as he was uninspired by existing 35mm SLRs made by other companies, but the Olympus sales division was clamoring for something just like everyone else had. Maitani had the philosophy that something isn’t worth doing unless it can be better or different than what was already available. His mission with the Pen series was to create a camera that minimized space while maximizing quality. He thought that if he were to get involved in a full frame SLR, he would need to bring that mindset to it’s development.

In late 1967, Maitani and Olympus management came to an understanding that work would begin on a new full frame 35mm SLR that would be different from what anyone else at the time was making. Two years into development of his new system SLR, Maitani showed a prototype of his new camera called the Olympus MDN.

The MDN looked unlike any other 35mm camera at the time, sharing a similar design ethos to medium format SLRs like the Hasselblad and Zenza Bronica. The camera was a completely modular design with a removable magazine film back, interchangeable viewfinders, and all new bayonet lens mount. The main body of the camera contained the shutter, reflex mirror, viewfinder screen and nothing else.

The image gallery above of the MDN prototype is courtesy, camerafan.jp.

The MDN was supposed to be the first in a series of Olympus MD cameras that would use the same lenses and support a wide range of accessories. A simpler model called the MDS (‘S’ was for Simple) would also be developed with a more traditional 35mm SLR body, but supporting the same lenses and could be sold for less money.

When presented to the sales staff at Olympus and at a camera show in 1969, reaction to the new MDN was extremely positive, but almost too positive. Olympus management was so excited, they wanted the camera ready for sale as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, due to the highly proprietary design of the new camera, it was deemed too expensive to produce in large quantities and required further development to reduce costs. As a result, Maitani was ordered to abandoned the MDN, and complete the simpler MDS instead.

By 1970, now seven years after the release of the Pen F SLR and three years after work began on the MDN, Olympus’s sales staff was getting impatient. Single Lens Reflex cameras were the most popular format of camera in the world, and with film prices dropping, the appeal of more economical half frame cameras was starting to slow. They needed something now.

With no release date in sight for Maitani’s new SLR, and development of an all new SLR typically taking around three years, Olympus knew they couldn’t afford to wait for yet another 35mm SLR to be created. There is much speculation on the Internet about the origins of this new camera, but in a 1976 interview with Maitani, he states that Olympus would purchase an existing design from an unnamed Japanese manufacturer and use that design as the basis to build their own SLR. Yoshihisa Maitani would state that he was in no way involved with the development and release of this new SLR, nor does he know who at Olympus was in charge of the project or which company the design was purchased from.

The Olympus FTL made it’s public debut in October 1970 at Photokina 1970 and went on sale in July 1971, barely a year after the decision was made to create an alternative to Maitani’s SLR. Although not an original Olympus design, the Olympus FTL was built by them to their quality standard, and featured the company’s excellent Olympus Zuiko lenses. To maximize compatibility, the camera used the “Universal” M42 screw mount which had been supported by a huge number of other Japanese and German companies.

Not content just to release a vanilla M42 camera without anything new, the FTL did have one trick up it’s sleeve which was that it supported through the lens (TTL) open aperture metering. Cameras with open aperture metering can take an exposure metering with the lens diaphragm wide open by detecting the position of the aperture ring on the lens and compensating the exposure reading by whatever f/stop the lens will stop down to when the shutter is fired. This was not a new feature for 35mm SLRs by 1971, but typically required a lens with a bayonet lens mount, rather than a screw mount.

The challenge with open aperture metering with a screw mount is that the exact position of the lens must be precise in order to accurately detect the position of the diaphragm. Screw mount lenses can be unpredictable when screwed onto the camera, varying with wear, user strength, or production tolerances. If the orientation of the lens is off by even a single degree from where the camera expects it to be, the reading will be off. Bayonet lenses do not have this problem as all bayonets have a positive locking position in which the lens is always fully attached to the body.

Olympus and several other M42 camera makers like Ricoh and Fuji solved this problem by slightly modifying the M42 mount by including a stop that would lock the lens in place when fully attached. For Olympus, they used a spring loaded pin on the body that would fit into a notch on the lens when the lens reaches the point where it is fully attached. A chrome release button was added to the front of the camera that must be pressed when removing the lens to disable the lock. A sliding lever near the bottom of the lens mount couples to a ring on the inside of the lens allowing the body to detect the exact position of the aperture ring. This coupling allowed the twin CdS meters in the FTL body to detect not only the selected f/stop on the lens, but automatically stop down the lens upon firing the shutter.

Upon release, a total of six Zuiko lenses were available for the FTL ranging from 28mm to 200mm including two 50mm lenses, one with a maximum aperture of f/1.4 and one f/1.8. Rumors persist that the M42 Olympus Zuikos are not of the same optical formula of equivalent OM-mount lenses, but this is unlikely as Olympus was already invested in the OM-mount (still called M-mount at the time), before the M42 lenses were created. In addition, Olympus likely never intended the M42 camera and lenses to be produced for long, so it is hard to believe that they would go out of their way to come up with all new optical formulas for a dead end mount.

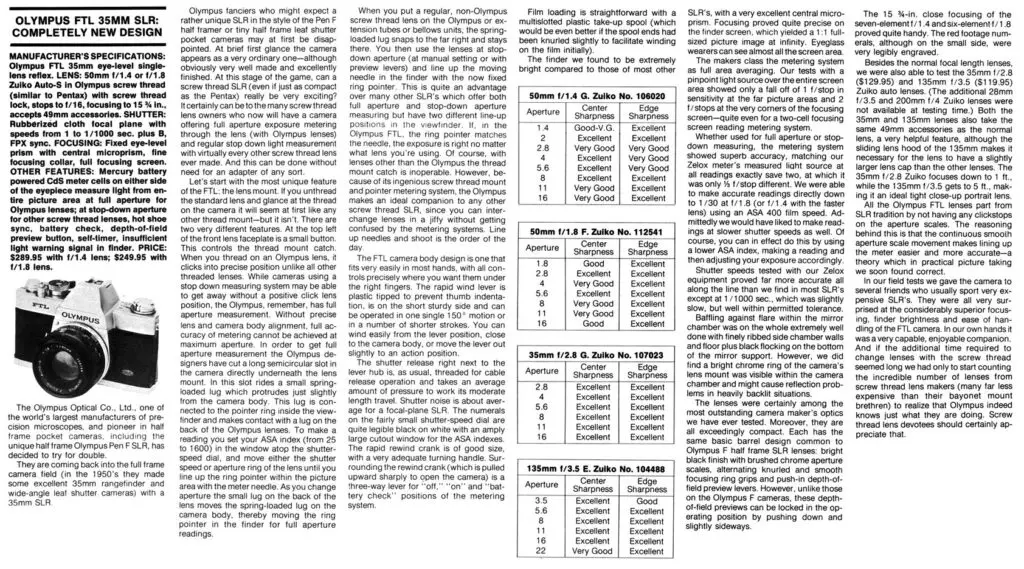

Despite being a “stop gap” system, Olympus did not cheap out on the FTL and it’s lenses as the M42 Zuiko lenses compare favorably to some of the best screw mount lenses ever made. Of the six lenses available, none had less than 5-elements with three of them being 7-element designs. In his book, “Collecting and Using Classic SLRs”, Ivor Matanle rates the screw mount Zuiko lenses very highly, with sharpness exceeding that of Asahi Takumar screw mount lenses.

In the Modern Test for the Olympus FTL above, each of the four tested lenses consistently rated Excellent at most f/stops with both the 50mm f/1.8 and 35mm f/2.8 lenses getting a perfect score across the board. Later in the review, the author states the M42 Zuiko lenses were some of the most outstanding Olympus lenses the magazine has ever tested. Praise was also given to the aperture rings which lack click stops, allowing for extremely smooth and precise control over the diaphragm for accurate metering.

Comments for the camera itself were also positive, praising the camera’s excellent build quality, accurate metering, the bright viewfinder, and the way in which Olympus solved the problem of open aperture metering using screw mount lenses. There was very little to complain about other than a slightly slow 1/1000 top shutter speed and lack of knurling on the take up spool which could have made loading film a tad easier.

When it was on sale, the Olympus FTL carried a retail price of $289.95 and $249.95 with the f/1.4 and f/1.8 Zuiko lenses respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $2150 and $1850, placing them in the high end of advanced consumer models.

In addition to the camera and six lenses, Olympus produced a whole system of accessories for the camera, including a bellows attachment, slide copied, extension tubes, and various viewfinder accessories.

At first glance, this forgotten SLR that was rushed to the market using a design created by someone else, you would be forgiven if you thought the Olympus FTL was an unremarkable camera, but you’d be wrong. As a preview of the excellence for the upcoming OM-system, the Olympus FTL was a faithfully high quality and capable entry into Olympus’s history as a maker of fine cameras.

The only real problem with the Olympus FTL is that it was never meant to last. A short seven months after it was released, Yoshihisa Maitani was ready to release his new Olympus M-1 SLR, which for how good the FTL was, the M-1 was better. Upon the Olympus M-1’s release, the FTL and it’s lenses were discontinued and Olympus would never made another M42 camera again. No records for how many Olympus FTLs were produced, but the best guess I have is less than 50,000 as they are difficult to find today, with the lenses even harder as their reputation for excellent optics has made them ideal to be adapted to other M42 35mm and digital cameras.

Today, the Olympus FTL is mostly forgotten. In my opinion, this has less to do with the anything bad about the FTL, but rather at how good the later OM-system was. Olympus hit a homerun with the OM-1 and later models and as such, are the SLRs that nearly everyone associates with the brand. While I am definitely happy that the company continued to release new models, I can’t help but be a little saddened that the FTL line didn’t continue. I wonder what an FTL-2 might have been like, but I guess we’ll never know!

My Thoughts

Occasionally when collecting cameras, you stumble upon a model which doesn’t seem to fit the mold by a certain manufacturer as it’s some sort of outlier to anything else that company did. Had Nikon made a TLR or Ihagee made an autofocus Exakta, those would be outliers. Although neither of those models exist, one such example is the Olympus FTL, a large bodied screw mount SLR released just before their extremely popular OM-series.

That Olympus made an SLR before the OM-1 (originally called the M-1) isn’t that unusual, but that it was only produced for 7 months and uses the only M42 screw mount Zuikos ever made, and offered open aperture TTL metering certainly ups the interest level of such a camera.

Looking for this model on eBay, there are few available and most of them are sold without a lens. The thing about having a very good but rare M42 lens is that there are a ton of other cameras, film and digital, that can use M42 lenses making them ripe targets for adapting. To find a working Olympus FTL with an original lens is quite difficult. It would take me over two years of searching to find one, but as often happens when putting out feelers for a specific camera, when you finally find one, sometimes a second one is right around the corner. So in a short window of time, I wound up with two FTL’s both with lenses.

Knowing that this was a camera that was originally designed by someone other than Olympus and then rushed out the door in a very short period of time, I didn’t know what to expect. On one hand, Olympus wasn’t known for putting their name on something that wasn’t good, but on the other, if there was one camera that they might have “phoned in”, this would be it.

When the first FTL arrived at my PO Box, I was immediately impressed with the feel and build quality of the camera. The camera did not feel cheap at all and matched what I hoped a larger Olympus OM-1 should feel like. Although the FTL is bigger, when placed next to an OM-1, the FTL isn’t as big as it first appears. Side to side the cameras are nearly the same, the FTL has a much higher prism and slightly higher shoulders than the OM-1, but otherwise there’s not as much difference as you’d think. Weight is about the only area where there is a significant difference as the OM-1 body weighs about 120 grams lighter

The top plate controls are very typical late 60s/early 70s Japanese SLR. A metal rewind knob with flip out handle is atop the meter’s power switch. A third position for the meter switch is marked “BC” and activates the battery check in which the match needle in the viewfinder should point to a battery check mark. On top of the prism is a flash hot shoe, which is an improvement over the earlier SRTs which only had a cold shoe.

To the right of the prism is a the shutter speed dial with speeds from 1 to 1000 plus an orange B for Bulb. The dial cannot be rotated a full 360 degrees and has a hard stop between Bulb and 1000 where a window showing the selected ASA film speeds is located. To change film speeds, lift up on the outer edge of the shutter speed dial and rotate it to select film speeds between 25 and 1600. While the shutter speed dial isn’t necessarily small, there is a decent amount of unused space to the left of and in front of the dial, suggesting that they could have made the dial a little larger and easier to rotate.

Above and to the right of the dial is the cable threaded shutter release button. There is no shutter lock feature on this camera. Next is the film advance lever which has a moderately long 157 degree motion for a single advance of the film. The wind lever is geared for multiple strokes, so if you do not wish to move the lever in one single motion, several smaller motions are allowed. An interesting thing about both of the Olympus FTLs I have is that both are missing a black plastic tip that should be on the end of the lever. In both cases this piece has fallen off at some point before the cameras came to me. A quick check of eBay for other FTLs produced one with the tip and one without it, suggesting this is a pretty common problem. Finally, on the far edge is the automatic resetting exposure counter.

The base of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket, rewind release button, the circular cover for the PX625 battery compartment and the camera’s serial number. The two cameras I have are numbered 109174 and 144920. As far as I know, no records of serial numbers for these cameras has ever been kept, so there’s no telling what the highest or lowest serial numbers might be, but the gap between these two suggests that at least about 35,000 exist between the two.

The back of the camera has little to see. A black rectangular eyepiece has grooves for some viewfinder accessories that were likely available, and a small round bump right below the rewind release knob are the only things to see. The circular bump does not appear to do anything or have any way to unscrew it, so I am not sure of it’s purpose. The black synthetic body covering feels well made and is not cracked, peeling, or otherwise damaged on either camera.

The sides of the camera are the same with the exception of a flash sync port with FP / X collar around it on the camera’s left side. Choose either of the two speeds for a flash gun to properly sync your flash. Both sides of the camera have a chrome metal strap lug for when some kind of neck strap is needed.

Lift up and tug on the rewind knob to release the door and the right hinged door swings open. Like the rest of the camera, the film compartment is very typical of Japanese SLRs from this era. Film transports from left to right onto a multi-slotted and non-removable plastic take up spool. Six different slots with a keyed tooth are there to make inserting the film leader very easy. When winding film, the take up spool rotates clockwise which wraps the film opposite of how it is stored in the cassette which is said to help with film flatness. Two sets of polished metal film rails are above and below the film gate. The cloth focal plane shutter has a thick rubberized coating to prevent light leaks. The shutters on both cameras appeared to be in good shape with no holes, cracks, creases, or other damage suggesting the curtains are made of a premium material. Inside the film door is a large metal film pressure plate covered in divots which help reduce friction as film passes over it. A metal clip on the door helps stabilize the film cassette as it sits in the camera. Like most Japanese SLRs of this era, the original foam light seals in the door channel and near the hinge have started to crumble, so should be replaced before using this camera.

Looking down upon the two Zuiko lenses included with these FTLs, it is clear these are not simply OM mount lenses with a different mount. While I cannot comment on the optical formulas being the same or different, the bodies of the two SLR Zuikos have many differences. First, the overall construction is that the screw mount lenses are constructed differently. The focus ring is black painted metal. There is no rubber grip coating any of the tactile parts of the lens like the OM Zuikos I have. Second, the aperture ring is located nearest the lens mount, like most SLR lenses. Most OM Zuikos have the aperture ring closest to the front of the lens. Another difference is the aperture rings on the FTL lenses do not have click stops. This was done intentionally to allow for very smooth and precise match needle operation so that in between f/stops can be chosen. Finally, although both OM and M42 Zuikos have a depth of field preview button on the lens, the FTL lenses have the button near the top, to the left of the depth of field scale, which in a way, kind of makes sense to put the button right next to the scale.

Once again, the front of the camera is pretty similar to most Japanese 35mm SLRs. To the left of the lens mount is the self timer lever. The self timer operates independently of the top plate shutter release. With it wound, you can continue to fire the shutter as normal, however in order to start the delayed shutter release, a small chrome button that is normally covered when the lever is in the upright position must be pressed to begin the countdown. With the lever moved as far as it will go and using a stopwatch, I counted just short of an 8 second delay from starting the self timer and the shutter firing. I was able to move the self timer lever part of the way to get an approximate 5 second delay, but anything less than that, and it wouldn’t engage at all.

The Olympus FTL uses the M42 screw mount which works the same as any other M42 screw mount SLR with one exception. As explained earlier in the history section, in order to accomplish the feat of open aperture TTL metering on a screw mount camera, a lock was added to the mount which when the lens is fully mounted, a pin slides into a notch locking it in place.

With the lens locked in place, in order to remove the lens, you must first press and hold a small chrome button near the 11 o’clock position around the lens mount. This makes the Olympus FTL, along with the Fujica ST901 and ST801 the only 35mm SLRs with a screw mount that lock their lenses onto the body when attached.

Looking through the viewfinder, the focusing screen is very bright, especially with the 50mm f/1.4 lens mounted. I have used a number of other M42 SLRs with some form of automatic and manual exposure, and most of them require you to stop down the diaphragm before an accurate reading can be taken, so being able to do this with the lens always wide open gives the Olympus FTL a very modern feel. You’ll almost forget you’re shooting a camera with a screw mount lens. The viewfinder is bright corner to corner and shows little to no vignetting near the corners.

In the center of the viewfinder is a small microprism circle, which to be honest, I didn’t love. I generally prefer split image focus aides, but when cameras don’t come with them, I expect the microprism circles to be a little bigger.

To the right is the match needle readout. Like many SLRs with this feature, a long black needle is coupled to the meter. A movable circle attached to the end of the arm is connected to the combined shutter and film speed dial. As you change shutter and film speeds, the circle moves. The object is to get the circle to line up with the meter needle and when that needle goes through the center of the circle, you will have proper exposure. Depending on which combination of film and shutter speeds you have selected, if you have a combination of speeds that is beyond the range of the meter, a red bar will appear blocking movement of the needle into impossible exposure readings. This is a nice feature which helps eliminate accidental underexposure, but doesn’t help you with overexposure. Lastly a small triangular notch on the right side of the camera is the battery check position when when the meter’s power switch is in the BC position, with a properly charged battery, the needle will point to this box.

My Results

When I received the first of the two Olympus FTL’s that first example had an issue with it’s shutter. At first, it would not fire at all, but then after some repeated “persuasion”, I was able to get it to fire maybe 1 out of every 3 attempts. Most of the time when it would fire however, the mirror would get stuck in the up position and I could not reset it to see through the viewfinder for any subsequent shots. At the time, not knowing that a second FTL was right around the corner, I took a snippet of bulk Kodak TMax and attempted to get a couple shots just to see if I could get a mirror selfie or some throwaway images.

Out of maybe 12 or so exposures, I got a couple duplicates of myself, plus two other keepers. The good news is that when the shutter and mirror behaved, the camera produced excellent images. It was clear these screw mount Zuikos delivered the goods, and I thought that if I couldn’t improve the consistency of this body, at the very least, I could shoot a roll with these lenses through a Pentax or some other screw mount SLR. But as lady luck would have it, I never had to result to such measures as FTL number 2 was right around the corner.

Thankfully, the second FTL was in better shape and each time I test fired the shutter, it behaved as it should. I didn’t notice any curtain dragging and the speeds sounded audibly different to the ear, so I decided the next roll should be color.

For the second roll, I chose an expired roll of AGFA Vista 100. This is an uncommon film that hasn’t been made in quite some time, so I didn’t know exactly how old it was, but I have shot expired Vista 100 before and found it to be unusually good for expired color film. I expected it to still shoot at box speed with a slight color shift.

For the second roll, I alternated between the 50mm f/1.4 lens that came with the first FTL and the 28mm f/3.5 lens on the other. I found the experience of the wider angle lens to be more enjoyable as I love “altered” perspective of a wide angle lens, but found that the slower maximum aperture darkened the viewfinder just enough to where I struggled to see focus in all but bright outdoor light.

Looking through the images, aside from the differences in focal length, I found the images to have excellent contrast and sharpness corner to corner. I noticed that the f/1.4 lens completely wide open was a tad soft as seen in the image of the liquor bottles, but still rendered the image nicely. Contrast was excellent, colors were accurate, and all of the images I shot showed no signs of the types of optical anomalies that inferior lenses suffer. As should be no surprise here, these 7-element Zuikos are awesome. I lack the sterile studio test capabilities to really tell you whether these are sharper than equivalent screw mount lenses by Asahi, Riken, Yashica, or Zeiss, but to my naked eye, I think they’re great and I am sure you’d think the same as well.

I cannot fault the first FTL for developing shutter issues as these are over half century old cameras and likely have gone decades without any service, so even with the failure of the first one, I still feel confident these were built to just as high of a quality standard as the contemporary reviews at the beginning of this review suggest.

For being larger than the later OM-series cameras, I found the ergonomics to still be excellent. The cameras are larger and heavier, but neither come anywhere close to being obtrusive. Side by side with something like a Nikon F2, the Olympus FTL feels like a compact SLR. If there was one area where the larger size actually benefitted the camera were the lenses. I actually enjoyed the wider grip of the focus and aperture rings, finding them marginally more comfortable to use than comparable OM-mount Zuikos.

The viewfinder, which is something I frequently put a lot of focus on in my reviews as I have poor vision and a bad viewfinder can make or break my enjoyment of the camera, was good. With the f/1.4 lens mounted, everything was as bright as any early 1970s SLR should be. The f/3.5 lens darkened it a bit which is to be expected, but when shooting at 50mm, I’d say the FTL was comparable to the best of what was available. Sure, later cameras like the Minolta XD11 or Nikon F3 would improve things, but apples to oranges, people.

Comparing the Olympus FTL to other 1970s SLRs, I can’t find much to complain about, or wish for. Sure, I wish Olympus had the foresight of Yashica to abandon mercury batteries and switch to silver-oxide cells, but few other companies in 1971 did that. Yeah, I guess the body generic styling of the body feels uninspired and does little to differentiate the FTL from almost every other camera of it’s era, but in building a camera designed by someone else, Olympus was able to rush this model out the door until the M-1 was ready. And okay, I guess auto exposure might have pushed this camera’s “gee-whiz” factor to an even higher level, but once again, adding even more technology would have likely delayed it’s release further.

No, I’d say the Olympus FTL is as perfect as it needs to be. Is it the best SLR or even screw mount SLR ever? Probably not, but it’s damn good, and with the screw mount Zuikos, is an extremely capable SLR and one that I would have no problem recommending to anyone reading this review. Sadly, with so few made, and even fewer still attached to their original lenses, finding a complete kit might be difficult, but if you happen to stumble upon one at anything remotely close to a price you can afford, definitely consider picking one up!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Olympus_FTL

https://www.biofos.com/cornucop/ftl.html

https://camerafan.jp/cc.php?i=561

https://cafe.toylab.jp/column/vintage-camera/12778/ (in Japanese)

https://www.photrio.com/forum/threads/olympus-ftl-camera-anyone-know-much-about-this-camera.125190/

Enjoyed this article. I owned the later OM-10 and enjoyed the heck out of it. Since people liked to see a bigger camera used when photographing a wedding, I used the OM along with my screw mount Leica.

The metering was great, and I would use the spot metering most of the time.

As you wrote the lens were really great to use.

I have a couple of these FTL’s. Strangely, they are almost always found with the black paint in the front engraving partly peeled out. I’d love to take one apart to look for design evidence but haven’t bothered yet. I’d suspect Mamiya – they make an SLR for anyone at that time. I’d love to know so that I could update my collector’s handbook – https://www.blurb.com/b/11190654-slr-compendium – excuse the shameless self-promotion!

The lenses are excellent but like the Fujica Fujinons they have than damn aperture pin which means that they will not mount on most M42 bodies. Screw mount Fujinons are more common of course and are often found with the pin ground off. To avoid this disgraceful vandalism I managed to modify an M42-Canon EF adapter ring with some difficulty by putting it in a lathe and cutting a rebate around the edge into the brass. Works well. Ironically the OM-1 wont take an M42 – too long a flange distance.

A few years ago I owned an FTL with the 1.8 lens, and agree that the build quality and handling were on par with the best SLRs of the era. I’d bet the body was built by Asahi (who may also have had some design input).

Here’s a link to user reviews of the Zuiko M42 glass; all are very favorable: https://www.pentaxforums.com/search/?q=olympys+ftl&cx=partner-pub-8894193256862854%3A3882095764&cof=FORID%3A9&ie=UTF-8

A few years back I bought an Olympus 50mm F/1.4. The website I bought it off of had it listed as an om lens. When it showed up with a screw mount, I did some research and found out it was for the above mentioned camera. I got a m4/3rds lens adapter but due to the lock pin on the back it doesn’t completely screw down to the adapter. I won’t be sawing off the pin as I hope to find an Olympus FTL one day to wed it too.

Mike, I think the open-aperture metering with only Fujica lenses was also in the Fujica ST705 and ST705w as well as the later ST801 and ST901?

It’s a nice write-up, but it’s very disappointing to see you repeatedly parroting the nonsense about the FTL being somehow “bought out”. I have read all the Maitani interviews and he makes various derisive and desultory comments about the FTL. The only thing that can be determined from these i comments is that nothing can be determined from these comments. Maitani obviously had nothing to do with the FTL, but Olympus had many other talented engineers on staff at the time. The notion that a rival company had a fully fledged set of plans for a camera as innovative as the FTL just sitting around is ludicrous and demonstrates a lack of understanding of the complexities of turning a set of blueprints into an actual product on store shelves.

I have communicated extensively with a person who worked closely with Maitani to document the history of his designs. The one thing he stressed was the difficulty of working with Maitani. He was overtly arrogant and it was a challenge to get him to answer questions. Maitani wanted to talk about what he wanted and that was the extent of it.

Tim, thanks for the feedback. I also agree that it seems odd that another company would have a full system 35mm SLR just sitting around waiting for some other company to buy/license it. That there is NO conclusive info on who this mysterious company might have been is suspect, as is the fact that there are NO other 35mm SLRs that look exactly the same as the FTL. It stands to reason that even if a third party company made the camera and licensed the design to Olympus as a “stop gap” model, that company would have likely also sold a version of it themselves. We’ve seen that practice many, many times before with Cosina, Chinon, and Mamiya designs that were sold under a variety of names.

But, as you likely already know, there still has yet to be any conclusive information either way. It makes no sense for Olympus to have two completely unrelated system 35mm SLRs in development at the same time. Time and time again, we know that the average length of time from conception to release of a 35mm SLR was at least 3 years. So for the FTL to be released in 1971, if Olympus designed the entire camera from the ground up, they likely would have started in 1968. It simply makes more sense that they outsourced or outright bought the design from someone else just to get something out there until the M-1 was ready.

If you’ve read other articles on my site, you’d know that I do my best to find the most accurate info that exists….I will include information that maybe can’t be 100% proven if the story is plausible enough and I can’t find something better. If you have another source that disputes the common interpretation of Maitani’s words that “someone else” designed the FTL, I’d love to hear it. I am always willing to update my reviews if I get something wrong. I just need to believe in the source enough to do so. Until that happens, I’ll leave the article as is. Thank you for your comment though, I am always looking to have the best information out there.

As a FTL owner, perhaps I can add a bit to the discussion above.

Maitani’s comments aside, it has always seemed unlikely to me that Olympus would have designed a new camera, set of lenses, and tooled up for such a short expected production run, especially when they were devoting their efforts and resources to the development of the OM system. So, who was behind the FTL?

To investigate this myself, I removed the bottom cover of my FTL and compared its mechanics to other SLRs of the day that it closely resembles including the Minolta SRT, Canon FT, and different screw mount models from Mamiya, Fujica, Pentax, Chinon/Cosina, and Ricoh. The FTL is clearly a different design. Mechanically it most closely resembles my Mamiya DSX 1000B, but it is not identical either.

Mamiya was my first guess, as they had been making similar screw-mount SLRs for some years, and cameras sold under other brand names. However, I recall a discussion in another forum suggesting that Nitto Kogaku may have been behind the design/manufacture of the FTL, a theory that is plausible for several reasons: Nitto had made cameras and lenses for Fuji, Mamiya, Ricoh, and possibly Olympus (Camera-Wiki states that Nitto made the Olympus Trip 35, but does not provide a citation). Some of Nitto’s Kominar lenses closely resemble the Zuiko lenses offered with the FTL. Also, both Mamiya (SX) and Fujica (ST) M42 SLRs came with locking lens mounts within a year of the FTL, so perhaps there is some connection there. Did Nitto license the locking mount design to Mamiya and Fuji, but sell the camera design to Olympus? And did they build it for Olympus, or did Olympus do the assembly? There’s no way to know for sure, but an interesting topic to research.

Though they seem fairly well-built, nearly all FTLs I have come across or seen for sale have had problems with dragging shutters and sticking mirrors, certainly with more frequency than similar SLRs from other major brands of the era.

Forgot to add the Mamiya (SX) and Fujica (ST 801 and others) screw mounts had not only a lens lock but coupling for full-aperture metering, like the FTL. (The Mamiya MSX/DSX SLRs were actually introduced in 1974, according to Ron Herron’s site.) Mamiya SX lenses will mount on the FTL, but meter coupling is in the wrong position. Pentax SMC lenses for the ES and Spotmatic F will not even mount on the FTL.