This is a Widelux Model F6, a 35mm panoramic swing lens camera made in Japan by Panon Camera Shoko Co., Ltd. starting in 1970. The Widelux is part of a series of panoramic cameras which all expose 24mm x 59mm images with a 126 degree angle of view on regular 35mm film. The Widelux series was produced from the 1950s until the 1990s, but despite such a long production time, only about 20,000 were ever built. All Wideluxes have a cult status made popular over the years by many different professional and amateur photographers, in addition to a particular Hollywood A-lister. As with all swing lens cameras, the Widelux is focus free, producing sharp images as close as 5 feet to infinity. The Widelux also does not have a traditional shutter, but offers comparable speeds from 1/15 to 1/250 second, a fully adjustable diaphragm, and a 26mm f/2.8 Panon lens.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), Up to 21 panoramic 24mm x 59mm images on a 36 exposure roll of film

Lens: 26mm f/2.8 Panon Lux coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: Fixed focus, ~3 feet to Infinity @ f/11, ~10 feet to Infinity @ f/2.8

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Panoramic

Shutter: Rotating Slit, Mechanically Controlled

Speeds: 1/15, 1/125, and 1/250

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Bubble Level

Weight: 830 grams

Manual (similar model): https://www.cameramanuals.org/prof_pdf/widelux_03.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Panon Widelux F6 and all cameras in the Widelux series are the pinnacle of swing lens panoramic photography. One of the most well known brands ever made, Widelux cameras maximize image quality while being incredibly easy to use, and usually pretty reliable. With care and practice, a Widelux can make good quality photographs for a lifetime of use. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 20% | |

| Bonus | +1 for a unique experience, difficult to recreate on few other cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.8 | ||||||

History

Panoramic photography today is a bit of a niche format, as most digital panoramic photos are manipulated either by a smartphone app to stitch many smallers images together, or cropped from a very high resolution wide angle photo. In the analog world, panoramas are almost as old as regular photos. A type of camera called the “cirkut” camera looked somewhat like a regular camera, except it was mounted on a motorized circular plate a top a tripod.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many companies produced Cirkut cameras, Eastman Kodak, Century, Conley, and others. Although the cameras looked different, they all worked the same basic way. The camera was focused using a ground glass plate and the motor wound up to a certain degree. Once the lens was focused, the ground glass was replaced with a film back containing special roll film in varying lengths.

Instead of being measured in numbers of exposures like normal roll film, cirkut film was measured in length. A typical roll of film could be anywhere from 5 to 20 feet long, with some special types much longer than that. All but the cheapest cirkut cameras could take photos of varying angles by adjusting the photo. One scene could be taken with a 90 degree rotation and another a 160 degree rotation, it just depended on how you set the camera.

Instead of firing a shutter, the lens was left wide open and a button or lever would begin the exposure by activating the motor which started to rotate the entire camera while also advancing the film to coincide with the motion of the camera. Once an exposure was made, the camera stops moving and the film stops advancing. The photographer would then either use some kind of punch to cut a notch in the film to indicate the end of an exposure. This would allow the entire roll of film to be developed at once, while the photographer could easily see where each exposure began and ended. Each company’s camera worked a little differently, but this is generally how it was done.

The most common, and easiest to make panoramic cameras around the turn of the 20th century were called “swing lens” cameras such as the Panoram-Kodaks. As the name implies, swing lens panoramic cameras have a lens that physically moves, or swings across the field of view to capture an image much wider than the lens could physically do otherwise.

Swing lens cameras usually use semi wide angle, small aperture lenses to maximize depth of field as there’s no easy way to focus a lens that moves. Not only that, these cameras don’t need a traditional shutter, as when the lens is stationary, it is oriented in a way that protects the film plane from light. Only when the lens begins to move does light pass through to the film, beginning the exposure.

The swing lens formula remained popular throughout the first half of the 20th century, but by the end of the World War II, new models had all but disappeared.

The next chapter for panoramic cameras began with a Russian weapons designed named Fedor Vasilyevich Tokarev who in 1948 created a prototype panoramic camera named the Fotoapparat Tokareva or FT for short.

The FT was built in the KMZ factory for the Soviet military and was not sold to the public. It was a simple box camera that used regular 35mm film in specially loaded cassettes which could take extremely wide panoramas across a 120 degree field of view, producing images that were 24mm x 110mm wide. An updated model called the FT-3 would be produced between 1952-53, but were also only produced for military or special use.

It is not clear exactly how many FT or FT-3 cameras were produced and for exactly what they were used for, but the design would stick around for another 10 years, when in 1958, KMZ would release an updated model called the FT-2 (ФТ-2) for civilian use. The FT-2 would retain the same basic brick like shape of the FT and FT-3, but would have different knobs and controls.

The FT-2 would not be sold outside of the Soviet Union but a similar, and much easier to use swing lens camera called the Horizont, also built by KMZ would. Produced from between 1967 and 1973, the Horizont would use 35mm film, but would use film in regular 35mm cassettes, eschewing the proprietary ones used in the FT cameras. In addition to easier to load film, other advantages to the Horizont was a more familiar form factor, a proper optical viewfinder, and a more flexible selection of shutter speeds.

The Horizont was primarily sold in the Soviet Union, Europe, and Australia, so if you were outside of those areas, your only other option was a camera called the Widelux made by a small Japanese company called Panon Camera Shoko. Panon was founded in 1952 by a man named Nakayama Shozo and originally produced a panoramic swing lens camera simply called the Panon. Instead of 35mm film, the Panon used 120 format roll film and produced six 2″ by 4.5″ images per roll. Like the original swing lens Kodak Panoram and the Soviet panoramic cameras, the Panon didn’t have a traditional shutter, but instead relied on a spring loaded barrel that rotated on a central axis, exposing film along a curved film plane with a lens as it swings throughout an arc on the front of the camera.

The Panon received very little attention in the United States other than the short article to the right from Modern Photography, where it was called a “novelty” and concluded that is was not a serious camera for amateurs or professionals.

Despite an underwhelming response from the American press, in 1958 Panon would release a second camera called the Widelux which took the same concept as the Panon, but shrunk it down to use 35mm film. Offering a more compact size and more accessible film, the Widelux also increased economy, offering up to 21 exposures per roll instead of six in the larger camera. Like the Panon though, the Widelux featured a swinging lens across a 140 degree (diagonal) / 126 degree (field of view), a fully adjustable lens diaphragm and 3 shutter speeds.

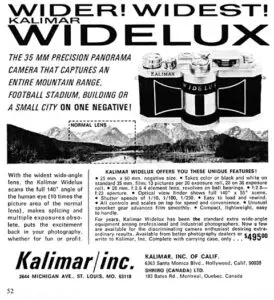

At first, the camera was only sold in Japan and wasn’t easily available out west until the mid 60s when the US distributor Kalimar started importing the model FVI. Kalimar branded cameras still had the Widelux name but an additional Kalimar plate adhered to the front of the body. The price for a US Kalimar Widelux in December 1965 was $495, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to around $4750, quite a hefty price to pay for such a limited use camera.

Throughout its life, the Widelux received incremental updates but never departed far from the original design. Every version of the Widelux had the same basic lens, a 26mm f/2.8 lens which was branded “Lux” on all but the earliest models which were branded “Vistar”, a 3 speed shutter, and very similar body. The selection of shutter speeds would be revised from 1/5, 1/50, and 1/200 on the earliest models, to 1/10, 1/100, and 1/250, and finally to 1/15, 1/125, and 1/250 on the later models. Some versions of the camera only came in chrome, some could be had both in chrome and black, and in the case of the Widelux F7 and F8, were only in black.

The Widelux was produced for a very long time with the last models ending production sometime in the mid to late 90s, but despite a nearly 40 year run, less than 20,000 are thought to have been made making it a pretty scarce camera nowadays.

Despite its rarity,. the Widelux is well known throughout the photographic industry. Collectors and amateur photographers seek it out for its handsome design, reliable operation, and excellent swing lens images. Although Soviet swing lens cameras like the Horizont, and later Horizon-202 models were more plentiful and can be purchased today for significantly less than any Widelux, none have the desirability of the Widelux.

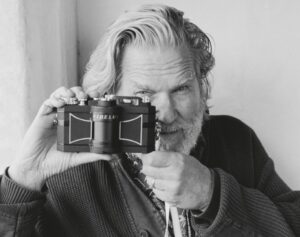

Further pushing the Widelux into pop culture lore is that it has been a favorite camera of Hollywood actor Jeff Bridges. Jeff has owned a Widelux since after his wedding in 1977 when he saw his photographer using one. Having seen one in operation when he was in high school, he sought one out, which his wife bought for him as a belated wedding gift.

Bridges frequently shoots images with his camera while making movies and has a huge collection of behind the scenes photos of actors and actresses while working with him on movies. Bridges is not shy about his love for the Widelux and will talk about it any chance he gets, including in several books he has written or endorsed, featuring many of his personal photographs shot with his camera.

Detailed records about the beginning and end of each model’s production are not known. Looking at serial numbers of different models, some were produced concurrently with previous models, so it stands to reason that a previous model’s availability did not always end when a new one came out. We don’t even know exactly when the last models were produced, but a fire at the Panon factory in the mid 90s suggests that’s about when production ended. According to the Japanese Wikipedia entry for Panon, it suggests that the company didn’t officially close until 2005, but it is not clear what they were doing in their final years, or even if that date is correct.

Despite being out of production for nearly 30 years, the Widelux has grown in popularity in recent years as people get re-interested in film, but also that Jeff Bridges won’t let people forget about them.

In the autumn of 2020, the photography magazine, Silvergrain Classics interviewed Jeff and his wife Susan to talk about his photography. During a very passionate discussion, the idea of reviving the Widelux came up with Jeff asking if anyone thought it was possible. Although at the time it seemed like an off the cuff fantasy, an idea was planted to see what it would take to reintroduce the camera.

Nothing was heard or said about a new Widelux until July 2023 when the Widelux Revival Project was announced with not only plans, but actual new parts. Silvergrain Classic editors Marwan El Mozayen and Charys Schuler worked in secret with Jeff and Susan, contacting German manufacturing firms to create new parts based off the Widelux F8. Although the intention is the make the camera as close to the F8’s design as possible, some manufacturing upgrades are planned to improve the reliability and operation of the camera. Although the final design has not yet been revealed, nor the entire specifications, in an appearance on Episode 52 of the Camerosity Podcast, Marwan suggested that the viewfinder may receive some upgrades.

Once the new camera is available, I will be sure to write about it and share what I know, but until then, we only have the original models. Although the Widelux was built to a high quality standard, it is very finicky and prone to an erratic movement of the swing lens. Even when new, Wideluxes need frequent exercise and good lubrication. If one has sat unused for too long, it likely will need some service before it can be reliably used. Sadly, there aren’t many places that can repair a Widelux anymore, but if you do manage to find one in good working condition, they are a historically interesting, photographically unique, and fun camera to use.

My Thoughts

Who doesn’t love panoramic cameras? I certainly do! I think of all the styles of cameras made, the swing lens panoramic camera offers both the most distinct shooting style and distinct looking images of anything out there. People pay CRAZY money for cameras like the Hasselblad Xpan which is really just a regular camera with a very wide angle lens that shoots 65mm wide images. Sure they look cool, but at prices north of $4000 and XPans more and more suffering electronic failures which are difficult to get repaired, the Hasselblad XPan (and its Fuji name variant) are not looking like wise purchases these days.

Of course Wideluxes can get pricey too and are also difficult to repair, I still feel like the combination of the unique look of a swing lens image, plus that it doesn’t suffer from vignetting, and there are no electronics to fail, make for a more compelling option. The thing is finding one. I picked up this Widelux last summer and couldn’t want to put a few rolls of film through it.

Compared to the Soviet Horizont, I appreciated the wider, but flatter body. The Widelux may have been a low production camera by a very small company, but it has the feel of a stout and reliable camera made by some other Japanese A-lister. The ergonomics are quite good with the most notable weakness being the viewfinder, but more on that later.

Up top, the controls should feel very familiar to most 35mm photographers. Certainly the Widelux isn’t a Leica, but most of the controls are as straightforward as one. On the left is the rewind knob and then a raised portion with the name and model of the camera, plus a reminder of where it was made and the film plane indicator. In the center is the shutter speed selector with only three speeds. This being the Model F6, this was the first model with the speeds 1/15, 1/125, and 1/250. Earlier models, including some lower numbered F6s have a different arrangement of speeds, but no matter which Widelux you have, there is only ever three.

You’ll notice up front, above the swing lens is a curved plate that reads Ultra-Wide Angle 140°. The claim of 140 degree is a bit misleading as they’re calculating a diagonal line, rather than a horizontal line which is the angle of view that the camera sees. The angle of view is actually 126° and is a much more useful number, but I guess 140° sounded cooler. Later versions of the Widelux remove the claim of 140°.

To the right is a green bubble level which is very important in images where horizontal lines, including the horizon, will be in the image. When shooting a swing lens camera, if it is not perfectly flat, you will get curved lines which almost certainly will ruin your image. Above the shutter speed dial is the aperture selector with selections from f/2.8 to f/11. Although the Widelux is a fixed focus design, the aperture selector controls what your minimum focus will be. The difference in minimum focus at f/2.8 and f/11 is about 5 feet down to 2.5 feet.

Next is the shutter release with external threads for a Leica style cable release. If you wish the use a cable release with the Widelux, you must unscrew the collar around the shutter release and attach a cable to the threads. This would be most useful for an auxiliary trigger release handle mounted to the tripod socket with shutter release cable. Although such a handle is not necessary for the Widelux, for some, it makes shooting panoramic images easier.

Pro Tip: On his website dedicated to using the Widelux, Jeff Daniels recommends that before shooting your Widelux, you “prime” the swing lens mechanism by manually rotating the barrel several times. According to him, this should help reduce the chances that the lens will move erratically across its motion while exposing an image. There is no risk of exposing your film when moving the lens manually as the light path remains blocked until pressing the shutter release.

Below the shutter release is the exposure counter, which counts up from 0 to a maximum of 21, which is the most amount of exposures you’ll get from a 36 exposure roll of film. The exposure counter automatically resets when removing the film back. Orange marks at 11 and 20 indicate where you’re likely to encounter your last exposure on a 20 or 36 exposure roll of film. Finally, on the far right is the film advance knob. Winding this knob not only advances the film, but it also tensions the swing lens, preparing it for the next shot. Winding the camera requires almost two full rotations of the knob, so it is a bit slow of a process that cannot be done in one single motion.

Flip the camera over and you’ll see the rewind release button which when pressed, disengages the film transport, and in the center, a 1/4″ tripod socket. Although not a very heavy camera, the Widelux would greatly benefit from being mounted to something at the center of its weight, rather than near one of the edges.

The sides of the Widelux are perfectly symmetrical with only a metal strap lug on each side. On many cameras the strap lug is angled forward to prevent the camera from tilting forward due to a heavy lens, but that’s not an issue here as the Widelux maintains its balance pretty evenly front to back.

Around back, there is the rectangular opening for the panoramic viewfinder, and on the door a rotating lock for the film compartment. The Widelux has an interesting design which would not be possible on a regular 35mm camera as the latch is on the inside of the door where a film pressure plate would normally be. Since film travels along a curved plane on a swing lens camera, there is no need for a pressure plate, which allowed the designers to put the lock right smack in the middle of the door. An unlock and lock position does exactly what they say and makes removing the door very easy.

Once you get the film door off, if you’ve never seen the film compartment of a swing lens camera, it will look very strange, but compared to other swing lens cameras, what you see is pretty similar. Like a normal 35mm camera, film transports from left to right into a fixed take up spool with a single metal clip. Unlike normal 35mm cameras however, the film does not take a straight path, rather it must travel behind a post, across the curved film plane, behind a second post, in front of the sprocket shaft, and then attach to the metal clip on the take up spool. It sounds super confusing, but once you do it a couple times, it becomes as easy to do as any other camera.

Many swing lens cameras I’ve shot usually have some sort of diagram on the inside of the film door to show you the correct path the film must take, but not this camera. There are many videos and guides online showing how its, but I always find it easy to just look at a camera with film already loaded as in the image to the right.

Up front, the camera certainly is pretty, but there are absolutely no controls. Swing lens cameras like the Widelux are actually pretty basic designs. Aperture and shutter speeds are controlled on the top plate, there’s no way to do flash and no self timer. No mirror lockup or depth of field preview buttons, or any other sort of lens release mount. Once you have film loaded into the camera, and the exposure set, there is nothing else left to do other than press the shutter release.

While there is a lot to love about the simplicity of the Widelux, one thing that most people don’t love, is the viewfinder. It is incredibly difficult to design an optical viewfinder that correctly shows an accurate representation of what will be captured by the lens as it swings across the film plane. The glass lenses in the viewfinder have a negative magnification and tend to distort the image, making for very blurry edges. Many regular uses of the Widelux often don’t even bother with the viewfinder, instead using the two red arrows on the top plate of the camera to get a feel for the angle of what will be captured, and the bubble level to make sure the camera is pointed at what you think it will be. While there is nothing stopping you from pointing your camera up into the sky or down at your feet, most people shoot this camera level with the horizon, so the bubble level is very useful for that.

All Wideluxes are well constructed and high quality, but easy to use cameras. Shooting them is unlike any other camera, but with practice becomes just as easy to do as with a normal camera. If this is your first time using the camera, my best advice to you is not to overthink it. Just take it out, shoot some candid photos and see what you get. Even if the images don’t turn out exactly as you had hoped, learn from your mistakes and try again.

My Results

Having never shot a Widelux before, but being fully aware of their most common issues which is even exposure due to lack or or dried lubrication, I wanted to do a quick test of the camera before taking it anywhere significant, so I split a roll of bulk Kodak TMax 100 I was shooting in another camera with the Widelux. A fun fact, is that I had shot only about half the roll in the first camera, but because of the much wider exposures from the Widelux, I was only able to get six exposures on the partial roll.

After developing that roll, I did see some unevenness in the exposure (often called ‘banding’), but it wasn’t too bad. Certainly not bad enough that I could justify the very high price to send this camera in for a CLA for, so I decided to just keep using it. Using a tip I got from Jeff Bridges’s website, I “exercised” the Widelux by manually rotating the lens barrel back and forth several times before shooting it. According to Bridges, and confirming the fact myself, with film in the camera, it is safe to manually rotate the barrel without fear of exposing your film as the shutter release has to be pressed before the film will actually be exposed.

So far in this review, I have talked about many of the benefits of a swing lens panoramic camera compared to other “crop” designs or cameras like the Hasselblad XPan which rely on an ultra wide angle lens. But one benefit I haven’t yet mentioned is the lens.

In a camera like the XPan, the lens must be carefully designed to maximize sharpness and contrast across the entire width of the frame. If you consider that all lenses are made of circular pieces of glass and project a circular image, when you turn that into a rectangular photo, the corners of that rectangle are closer to the edges of the circular image. Since light tends to fall off and blur near the edges, you have to be careful to not wind up with a panoramic image that is significantly darker or blurrier near the edges. In the XPan, this is overcome with both with a very complicated and expensive wide angle lens and a special neutral density filter that is darker in the center than the edges. While this method does work, it significantly adds to the cost of the camera, raising their price in new and used markets.

Swing lens cameras however, do not expose the entire frame all at once, but rather use a sweeping motion to expose a small slit at a time. This means that the center part of the lens, where the image is sharpest and brightest, moves across the entire film plane exposing each part of the film as it passes by. The advantage to this is that the edges of the image are just as sharp and bright as the center because the best part of the lens exposed the entire image. As a result, designers of swing lens cameras can use simpler and less costly lenses which don’t ever need to take into account edge sharpness. The lens in the Widelux is a simple Tessar style 4-element lens which is good enough to return an image with excellent sharpness edge to edge, with little to no light fall off.

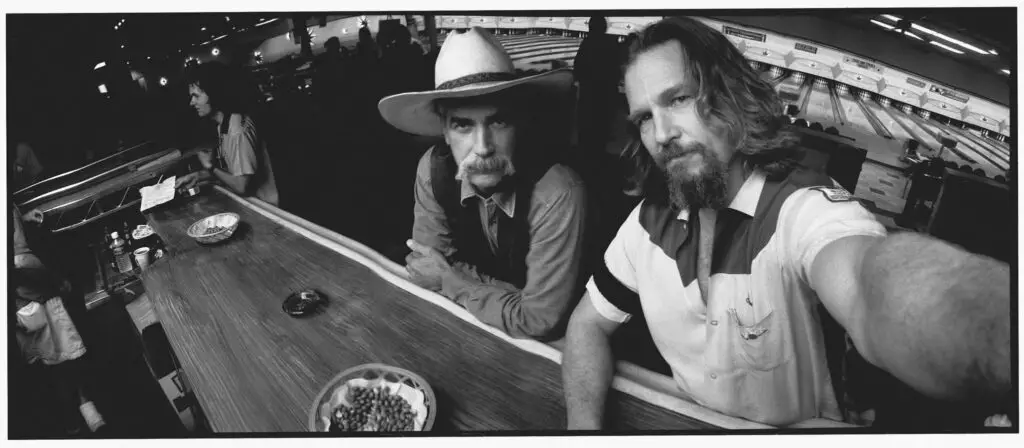

Looking at the images from the Widelux, these are as good as any panoramic images I’ve ever seen. If you enlarge any of the images from the gallery above and look at them on a large desktop computer monitor, you’ll see detail that approaches medium format. If you were to make a print of a Widelux image, you would have no problem making small banners 40 inches wide or more without significant loss of detail.

Swing lens cameras aren’t perfect however, since the actual act of making the photo requires the lens to completely finish its motion, which at the slowest speed, takes almost 3.5 seconds for the image to finish being exposed. In order to do this without distortion to your image, stabilization or a very steady hand is a must. If you are going to channel your inner Jeff Daniels and use your Widelux as a candid point and shoot camera, you’ll want to use one of the faster speeds and use fast film to lessen your chance of blur.

Beyond the image quality though, another challenge I found with shooting the Widelux is “seeing a panoramic” image. While the viewfinder on the Widelux is not the greatest, I am not referring to the actual viewfinder, but more what my mind’s eye sees when I compose an image. As I use more and more cameras, I often find that my best images are the ones I can compose in my head before capturing them on film. This isn’t difficult with a camera that shoots 3:2 or 1:1 aspect ratio images, but when you get into panoramics, my brain doesn’t naturally see in the Widelux’s 5:2 aspect ratio. Of course, this is something that varies person to person, and with practice can be improved, but the difference between a person who is shooting the Widelux for the first couple times, you likely won’t get as great of compositions as an experienced veteran.

That said, even if you are new to the Widelux, and you haven’t quite mastered the art of seeing in panoramic, or maybe didn’t use the best stabilization while using it, shooting the Widelux is a heck of a lot of fun. The resulting images have the ability to change the look of a scene, giving it expansive dimensions and geometry that regular cameras can’t. When done correctly, a panoramic image can make even the dullest of scenes look fantastic, showing details you likely would have missed in real life.

If you frequently shoot in public spaces, this camera will attract attention. Most people likely have never seen a swing lens camera before and will be attracted to its unique looks and the noises they make while firing, so they’ll want to ask you questions about it. But also, if you manage to run into someone who has seen a Widelux and knows what it is, they too, will also want to ask you questions about it! So be prepared, if you want to make some images with your camera, you’re going to want to factor in a little extra time before you get back!

If a Widelux is what you want, then a Widelux is what you should get as there simply is no better option for making true panoramic images on 35mm. Sure, Soviet Horizonts are less expensive, and the East German Noblex cameras are pretty good when they work, but reliability concerns with both cameras and extremely high prices on the Noblex wouldn’t make either my first recommendation.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Widelux

https://manualcamera.info/widelux.htm

https://www.haroldfeinstein.com/wide-wide-enough-adventures-widelux/

https://www.jrwyatt.com/new-blog/2021/6/11/the-widelux-f6-and-tri-x-400

https://www.jeffbridges.com/tipsonwidelux

https://www.ultrasomething.com/2011/05/a-long-look-at-a-widelux-1/