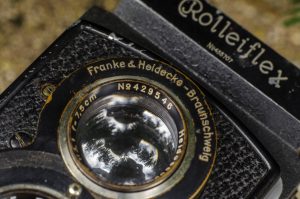

This is a Rolleiflex Standard K2 Twin Lens Reflex medium format camera, built by Franke & Heidecke Brunswick between the years 1932 and 1938. This model was the first revision to the original Rolleiflex from 1929 and upgraded the camera with several significant features, including support for 120 format roll film instead of 117 roll film, a film rewind crank, sports finder, removable back, exposure counter, support for 35mm film, and an optional f/3.5 Tessar and Compur-Rapid shutter. The very next model that replaced it was also called the Standard, so as a result, has earned the nickname as the “Old Standard” although that never appeared in any promotional material at the time. It was the first camera made by Franke & Heidecke to garner worldwide attention and set the standard for what a Twin Lens Reflex camera should be.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens (taking): 7.5cm f/3.5 Carl Zeiss Tessar uncoated 4-elements

Lens (viewing): 7.5cm f/3.1 Heidoscop-Anastigmat uncoated unknown elements

Focus: 3 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coupled Reflex Viewfinder with Ground Glass and Spirit Level Focusing Screen

Shutter: Compur-Rapid Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 776 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/rolleiflex/rolleiflex_standard_english.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Rolleiflex “Old Standard” K2 Model 622 is a handful of a name for what was the followup to the original Rolleiflex TLR. Offering a large number of upgrades from that earlier model, the “Old Standard” was the model that elevated Franke & Heidecke to one of the most highly respected camera manufacturers of the 20th century. This was the first Rollei to use 120 roll film, have a film advance lever, and a removable back. Although it lacked many of the features that later Rolleiflexes would come with standard, it was still a very well built and innovative camera upon it’s release, and remains one of the most collectible cameras ever made. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, not the first, not the best, but one of the most unique cameras ever made | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.2 | ||||||

This review is about the Rolleiflex Standard K2, one of the earliest models in the Rolleiflex lineup, but it’s story begins with a completely different company than the one who built it. To fully understand how the Rolleiflex and it’s parent company, Franke & Heidecke came to exist, we need to talk about Voigtländer.

Voigtländer is the oldest name in photography, having existed as far back as 1756 in Vienna, Austria. I’ve covered these early days of the company’s history before if you’d like to read more, but for this part of the story, we’ll start in the early 20th century around the time Voigtländer had made a serious push into producing their own cameras.

On January 10th, 1900, Voigtländer would hire a 20 year old mechanic named Reinhold Heidecke who worked in the company’s factories as a designer. Between the years of 1904 and 1905, he would temporarily step away from the company to serve in the German military. Upon his return to Voigtländer, he would be promoted to a production manager. Heidecke was an excellent designer, and in his new role he would help Voigtländer with many of their early folding camera designs.

In 1909, an intern named Paul Franke worked in sales for Voigtländer where he would start to develop connections within the German photo industry. Paul Franke was an excellent salesman and would quickly learn the business of exporting and in 1912 would leave the company to work for a rifle scope company called Géhard, likely in some type of sales role. A large number of Géhard’s sales went to other European countries and the United States, and with the start of the first World War in 1917, the company’s sales would come to a halt, causing the company to quickly go out of business, leaving Franke unemployed.

Shortly after, Paul Franke would form his own company called Franke & Co. whose products were mainly rifle scopes, microscopes, and binoculars. Franke’s skills in sales and connections within the German optics industry earned him contracts with the German military. With the war, demand increased to the point where Franke had to reconnect with his old company and start to offer products built by Voigtländer.

It was at this time when Paul Franke would meet Reinhold Heidecke and the two would form a friendship that would last decades. With Franke’s strong business mind and his contracts supplying the German military, and Heidecke’s previous military experience and eye for design, the two men started working on an idea they had for a new type of camera ideal for battlefield photography.

Until this time, if you wanted a portable camera suitable to be carried by a soldier, your only good option was some kind of compact folding camera. In 1912, the Eastman Kodak Company would develop a compact camera called the Vest Pocket Kodak. These cameras were collapsible roll film cameras that used a leather or synthetic bellows system connected to a moving lens and shutter assembly. Although Kodak’s Vest Pocket design was very popular, many companies including Voigtländer copied it, creating their own versions of Vest Pocket cameras. This new style of camera became very popular during the war, and were given the nickname of the “soldier’s camera”.

Many vest pocket cameras were sold and used by participants on all sides of the war, but both Franke & Heidecke saw several flaws with the design. For one, the bellows were fragile and could not handle dirt or moisture well which would cause holes to form, thus rendering the camera useless. An often told story is that Reinhold Heidecke once left a folding camera in his basement over night and rats had chewed through the bellows which further confirmed this flaw. Furthermore, the design of the camera’s tiny viewfinder required the photographer to either hold it at eye level, or at chest level, requiring the photographer to put himself into harm’s way if he wanted to photograph a battle.

In an effort to overcome all of these shortcomings, Reinhold Heidecke came up with the clever idea of a new solid bodied camera that used a reflex mirror which could work like a periscope to shoot photos. A soldier could use this camera in the trenches and hold the camera above his head and photograph something without ever having to stand up. The camera would have a large, life size viewfinder that would allow it to be used at an arms length, rather than eye level, further simplifying composition. Finally, the camera would have a solid body, and wouldn’t need bellows, meaning it was more rugged and able to handle the poor conditions of a battlefield.

Both Franke & Heidecke would attempt to convince the leadership at Voigtländer to build their new reflex camera, but for reasons I couldn’t uncover, they were unsuccessful. Voigtländer must have thought the new design to be too complicated, or perhaps they didn’t see the appeal of re-inventing photography in the middle of a war, especially when there was already demand for Vest Pocket cameras.

Unfazed by Voigtländer’s reluctance to produce the camera, in 1920, Paul Franke and Reinhold Heidecke would form their own company, simply called Franke & Heidecke. Although their purpose for starting a new company was to produce their new camera, working without the support of a major optics company, the men needed to build something that they were already familiar with that could be sold easily and help build capital in the company. For that, they chose a glass plate stereo camera which they would eventually call the Stereo Heidoscop. This was a design that Heidecke had a lot of experience with while working for Voigtländer, so they were able to put together their own design rather quickly.

Along with Paul Franke’s sales and business skills, the new stereo camera sold very well. Demand for Franke & Heidecke’s stereo cameras helped grow the company quickly, and by 1923 required them to move to an all new 60,000 sq ft factory. That same year, a new roll film version of the Stereo Heidoscop that used 117 format roll film was introduced that was called the Rollfilm Heidoscop. This new camera had the nickname of “the Rollie”, a name which the company would eventually be named after.

In 1927, the time came for Reinhold Heidecke to finally build his new twin lens reflex camera, and a prototype of the new Rolleiflex was introduced. Over the course of the next year and a half, a total of 11 different prototypes were built, refining the design of the camera until it was ready for commercial production. A very small number of early cameras were built in 1928, but it is widely accepted that the first year of availability for the Rolleiflex was 1929.

The Rolleiflex was an immediate success. Between 1929 and 1932, over 35,000 examples were produced of what was internally called the Rolleiflex K1. These original Rolleiflexes were the only models with a film advance knob instead of a lever, came without a hinged back, and the only ones designed for an earlier type of roll film called type 117 which was identical to 120, but was shorter, offering fewer exposures per roll. A popular conversion at the time was to convert these cameras to use type 120 film, so finding an unmodified example today is very hard to do.

In 1932, an updated Rolleiflex, known as the K2 made it’s debut upgrading quite a number of things, such as:

- Support for the longer 120 format roll film allowing for 12 exposures per roll of film

- Relocated the red film window to the bottom of the camera (some exist with red windows on the back and bottom)

- Support for 35mm film using a separate Rolleikin adapter

- Film advance lever in place of the knob

- Removable film back which allowed it to be used with a special plate film adapter

- An “eye mirror” sports finder that was unique to this one model

- Optional upgrades to a Compur-Rapid shutter and Zeiss Tessar 3.5 lens

Also available with the Rolleiflex Standard was a smaller version, designed for 127 format roll film that took 4cm x 4cm images. Nicknamed the “Baby Rollei”, this smaller version looked very similar to it’s larger brother.

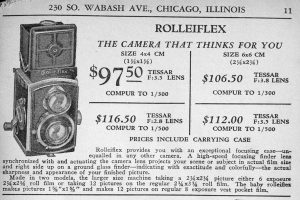

The Rolleiflex was built to the highest levels of quality and was priced at a level that kept it out of reach of most casual photographers. In their 1935 catalog, Central Camera from Chicago, IL advertised the full size Rolleiflex with f/3.5 lens and case for $112. You could save $5.50 by stepping down to the f/3.8 lens. When adjusted for inflation, these prices are comparable to $2060 and $1965 today.

The K2 Rolleiflex was an even greater success than the first model, and helped elevate Franke & Heidecke to the upper echelon of German camera makers. It was in production from 1932 – 1938 and sold over 95,000 examples which was a very high number considering the camera was usually out of the the price range for all but professional photographers.

In the years that would come, Franke & Heidecke would release a constant update of new Rolleiflex models, incrementally upgrading, but not radically changing the formula. A parallel model called the Rolleicord would make it’s debut in 1933 alongside the Rolleiflex offering a simplified and less expensive feature set. Over the course of the next 2 decades, Rolleiflexes would revolutionize professional photography and until the widespread use of 35mm rangefinders and SLRs in the 1950s, would remain the camera of choice for press and studio photographers.

Rolleiflex cameras never need any introduction as their role in the history of 20th century photography is well documented. Despite changing trends and needs in the photographic industry, Rolleiflexes stayed in continuous production until the early 1980s with various special edition re-releases occurring as recently as 2000. If you’ve seen any photos taken by any news source from the 1930s through early 1960s, the odds are very good that you’ve seen at least some photos taken with one. Countless professional, semi-pro, and amateur photographers such as Vivian Maier owned and shot Rolleiflexes.

Today, there is a market for pretty much every Rollei ever made, whether it’s a -flex or a -cord, with earlier and more basic models selling for under $100, to the more desirable 2.8 models or special editions fetching several thousands of dollars. If you find a Rolleiflex, regardless of which one, you should take notice. Don’t overpay for a less desirable model, but even the worst Rolleiflex ever made is still a pretty darn good camera.

Repairs

This Rolleiflex came to me in quite a rough shape. Not only was the whole body dirty and showed heavy signs of use, the “Rolleiflex” name plate was cracked, the viewing screen was cracked, the shutter speed and aperture selectors were difficult to move and felt gritty, and the shutter was completely seized. While Rolleiflex TLRs are generally beyond my normal ability to repair, this earlier version had what appeared to be a normal 1930s era Compur leaf shutter that probably just needed a good flush.

As I typically try to do any time I flush a leaf shutter, I like to completely remove it from the camera so that I can unscrew all of the glass out, and completely submerge the shutter in naphtha oil (lighter fluid) and allow all of the old lube and whatever other grime has gotten in there a chance to dissolve. I usually lubricate a few of the pivot points and other friction points with white lithium grease and see where that gets me.

From my limited experience working on Rolleiflexes, the “Old Standard” model is quite a bit easier to take apart than later Rolleiflexes. I probably would not have attempted this repair on a later model, but if you want to try to do it yourself, here’s what I did.

Looking at the front of the camera, you can see six screws. The bottom four screws (indicated by yellow arrows) are larger than the top two (indicated by red arrows) and need to be removed to separate the entire front plate from the camera. Beneath each of these four screws is a metal washer which you don’t want to lose. Carefully unscrew these screws and place them and the washer in a safe location. Do not remove the red screws yet.

Carefully lift the front of the camera off the body. Unlike later Rolleiflexes that use a helix of some type to control focus, this camera has a unique system of four rotating posts that all work in tandem to push and pull the front panel fore and aft as you focus the camera. Each of these four posts MUST be in the correct orientation when putting the camera back together, so pay attention to what they look like immediately after lifting the front off. You may want to take some digital pictures of the camera at this point so you can remember what it looks like when you are putting it back together.

Carefully lift the front of the camera off the body. Unlike later Rolleiflexes that use a helix of some type to control focus, this camera has a unique system of four rotating posts that all work in tandem to push and pull the front panel fore and aft as you focus the camera. Each of these four posts MUST be in the correct orientation when putting the camera back together, so pay attention to what they look like immediately after lifting the front off. You may want to take some digital pictures of the camera at this point so you can remember what it looks like when you are putting it back together.

With the front of the camera off, flip it over and remove the 4 screws indicated by the blue arrows (do not remove the red screws). This will allow you to completely remove the shutter and taking lenses off the front panel.

With the shutter removed from the panel, you should be able to unscrew all three lens groupings using a standard lens spanner or by hand. Be careful not to scratch the glass.

Using tweezers or a small screwdriver, rotate the little locking screw (the thing with the two small divots) 180 degrees, so you can rotate the front shutter ring off. At this point, you can flush the shutter. Most Compur shutters look very similar to one another, so if you’ve done one before, the shutter on the Rolleiflex should look familiar to you. If this is your first Compur, just take lots of pictures of the shutter at various angles so that you may put it back together when you are done. The speed ring (the thing you turn to change shutter speeds) needs to be lifted off to get inside of the shutter. You can still fire the shutter with the speed ring off, but it will only work in Bulb mode like this. You’ll need to reattach the speed ring to fire it at any other speed.

My process for this is to let the shutter sit in a small glass dish for about 5 minutes and then drain the fluid. I use Q-tips to get any excess gunk out, and then give it a second 5 minute flush, firing the shutter several times while it is wet. Once I’ve cleaned it sufficiently, I pour out all excess naphtha and then let it sit out overnight to dry.

Step 5:

Whenever you clean a shutter, you should not put it back into the camera until you are absolutely sure everything is dry. Naphtha evaporates relatively quickly, and being exposed to open air for 8-12 hours is usually enough, but sometimes it may take a full 24 hours to dry. Sometimes even after drying, there may be some debris remaining on the shutter blades, so you should gently wipe away any excess gunk that is still in the shutter before putting it back together. Assuming you are at that point where the shutter is firing correctly at all speeds, reinstallation is the reverse of how you got it out.

Take care when putting everything back together to make sure each of the four posts that control focus are in the correct orientation. You’ll notice a small protrusion sticking up that needs to set into a matching divot on the back of the front of the camera. If these four posts are not perfectly aligned, the plate will not go on correctly.

Take care when putting everything back together to make sure each of the four posts that control focus are in the correct orientation. You’ll notice a small protrusion sticking up that needs to set into a matching divot on the back of the front of the camera. If these four posts are not perfectly aligned, the plate will not go on correctly.

Once you have the front plate attached, you should confirm the camera focuses correctly. It is possible that the taking lens is correctly installed, but the image projected into the viewfinder is not calibrated. You can adjust the focus of the image in the viewfinder by turning the viewing lens. Remember the two screws indicated by red screws in steps 1 and 2 above? This where you would loosen those to remove the viewing lens. With it removed, you can screw this lens in or out to fine tune to focus of the image in your viewfinder. This may take some trial and error and might even require installing some type of ground glass in the focal plane of the camera to get it right, but once you are sure you have it correct, you can put everything back in the opposite of how you removed it.

Step 6:

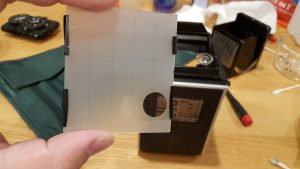

As is the case with most old TLRs, the viewfinder and reflex mirror can often benefit from a cleaning, or in the case of where the mirror has lost it’s silver coating, might even need to be replaced. Replacement mirrors are available from Martin Seelig on eBay (seller ID marty1107) for about $10 shipped, and replacement focusing screens are available from Rick Oleson at his website. If you order a new screen from Rick, not only will they be perfectly cut to fit your camera, but they will also be considerably brighter than the stock one as well. With a new mirror and brighter viewfinder, old TLRs like the Rolleiflex Old Standard can be as bright as cameras made decades later. This is also a good opportunity to clean the inside of the camera including the back of the viewing lens.

As is the case with most old TLRs, the viewfinder and reflex mirror can often benefit from a cleaning, or in the case of where the mirror has lost it’s silver coating, might even need to be replaced. Replacement mirrors are available from Martin Seelig on eBay (seller ID marty1107) for about $10 shipped, and replacement focusing screens are available from Rick Oleson at his website. If you order a new screen from Rick, not only will they be perfectly cut to fit your camera, but they will also be considerably brighter than the stock one as well. With a new mirror and brighter viewfinder, old TLRs like the Rolleiflex Old Standard can be as bright as cameras made decades later. This is also a good opportunity to clean the inside of the camera including the back of the viewing lens.

To get to both the focusing screen and reflex mirror, simply remove the four screws (two on each side) from the edge of the viewfinder. Once the viewfinder is off, both the screen and the mirror are held in place with clips. If you plan on reusing your old ones, be very careful as they’re both made of glass.

To get to both the focusing screen and reflex mirror, simply remove the four screws (two on each side) from the edge of the viewfinder. Once the viewfinder is off, both the screen and the mirror are held in place with clips. If you plan on reusing your old ones, be very careful as they’re both made of glass.

When reinstalling the focusing screen (whether the original or a replacement), I found that it was a good idea to put small pieces of electrical tape on the edges of the screen near where the clips are, to give it a little bit of protection.

When reinstalling the focusing screen (whether the original or a replacement), I found that it was a good idea to put small pieces of electrical tape on the edges of the screen near where the clips are, to give it a little bit of protection.

Once the mirror and focusing screen are both installed back into the camera, you can reassemble the viewfinder in the opposite of how you removed it and you’re ready to load up some film and shoot your camera.

My Thoughts

My journey collecting and using old cameras has been a long one, but for the first couple of years, that journey never included a Rolleiflex, at least not a real one. But one day while browsing a local antique shop, I came across this one in poor shape, it was covered in dirt and inoperable. I covered what it took to bring the camera back to life in the previous section, but once it was working, the camera revealed itself to still have some life left in it.

Although it’s not the original model from 1929, the Rolleiflex Old Standard still has much of the design details of the “wartime trench camera” that Paul Franke & Rudolph Heidecke pitched to Voigtländer. The black paint and nickel body with genuine leather covering showed a lot of use over the years, and I even saw an engraving of a Social Security Number by the original owner on the side of the lens standard. This was common practice in the 50s and 60s as a means to discourage theft.

Compared to later TLRs in my collection like the Yashica-Mat or the Minolta Autocord, the Old Standard is relatively lightweight as it lacks some of the more complex functions of later cameras. The first thing I found interesting about the Old Standard is the focus wheel. While it seems to work similarly to other TLRs, the knob turns more than a full 360 degrees to get from the minimum to maximum focus distance. This seems a bit odd to me, but assuming you rely on the focused image in the viewfinder, it’s hardly a problem.

On the camera’s right side is the film advance lever. Although a stalwart of every Rolleiflex that would come after it, the presence of a lever was cutting edge stuff when the Old Standard was released as the original Rolleiflex had a knob. Near the 1 o’clock position of the center of the crank is the automatic exposure counter. This counter was capable of counting each of the twelve 6×6 exposures the camera could make. Unlike later Rolleiflexes however, the Old Standard lacked the ability to detect the start of the film, so a red window on the bottom of the camera was used to set the film to the first exposure, at which point you use this counter for everything else.

The bottom of the camera features the previously mentioned red window which is needed to find the number 1 on a new roll of film as the camera lacks the ability to detect the start of a new roll of film. The location of this red window on the bottom corner of the camera, as opposed to the center of the door like on other “lesser” TLRs of the 20th century is because when this camera first went into production, it was not yet common for film makers to indicate 6×6 exposures down the center of the backing paper. Most 120 film of this era only had eight 6×9 numbers near the edge, so the location of this window is needed for the first 6×9 frame, which so happens to be the correct starting point for a 6×6 image. The only other things visible on the bottom is the 3/8″ tripod socket and film compartment release latch.

The back of the camera features both a depth of field calculator on the back panel of the viewfinder and a primitive exposure recommendation chart on the back door of this camera. All of the text is in English, but the depth of field chart is in meters, suggesting this specific camera was marketed in English speaking countries that used the metric system.

Releasing the film door lock on the bottom of the camera opens the top hinged back of the camera. Although a top hinge is common on Rollei cameras, I find it quite awkward and something other companies such as Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta) improved upon with the Autocord. The entire back of the camera can be completely removed by loosening two small screws near the hinge. This is needed for the optional sheet film adapters that was available for the Rolleiflex. If you’ve ever used a later Rolleiflex, you’ll know that loading film into the camera requires feeding the paper leader in between two rollers which are required to detect the start of the film. The Old Standard does not have this feature, so loading film merely requires the paper going over both rollers.

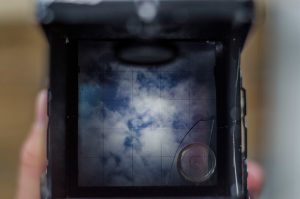

Like all TLRs, the Rolleiflex has a waist level finder which allows a life size composition of a 6×6 image. There is also an optional swing out magnifying lens (not shown) that can be used for precision focus. Like other TLRs from the 1930s, the image through the ground glass is quite dim. Center brightness is adequate enough, but a strong vignetting is evident near the edges. If you had plans to use the Rolleiflex Old Standard regularly, you might want to consider some type of brighter aftermarket focusing screen, such as Rick Oleson’s BrightScreen. In the bottom right corner, you’ll notice a little circle, which was a feature called a spirit level which originally had some type of liquid in it with a small air bubble that could be used like a bubble level to aide in leveling the camera. In this example, the liquid has long since dried up, so it no longer serves a purpose.

Like most other TLRs, the Rolleiflex Old Standard has what’s called a “sports finder” which is a way to quickly estimate 6×6 compositions without using the focusing screen. This type of finder is good for fast action “sports” photography at or near infinity. Unlike other TLRs though, the Old Standard has one of the most unique implementations of a sports finder I’ve seen.

Using the sports finder is rather difficult to explain with words, and requires the camera in your hand to fully understand how it operates. The image to the left is from the Rolleiflex’s user manual and shows the user positioning his eye directly behind a round concave mirror in the middle of the cross hairs. There is a small hole through the center of the mirror that you must position the pupil of your eye in. The idea is to fill the entire mirror with an image of your eyeball, with the pupil blocked out by the hole, and when your eye is in this exact position, the entire contents of the outer frame (ignoring the cross hairs) will be the composed image. If this sounds overly complicated and contrary to the intent of a sports finder, you’re right, and is probably why this is the only camera this design of finder ever appeared. Franke & Heidecke wisely revised the design for all later Rolleis.

The Rolleiflex featured what the user manual called the “3-point control” which was the ability to control all critical functions of the camera at only three points. Each of the three points are at the 3 o’clock position the aperture control, at the 9 o’clock position the shutter speed control, and at the 6 o’clock position a dual lever that both sets and fires the shutter. There is no shutter release on this camera like later Rolleis. To properly cock and fire the shutter requires pushing this bottom lever to the left until you feel the shutter cock, and then back to the right to fire it. It’s a surprisingly effective and comfortable, although not obvious, method for control.

Although changing shutter speeds and aperture f/stops is done via the two levers around the perimeter of the shutter, through a complex internal linkage. a display above the viewing lens facing upward will show the selected settings. This is very handy when holding the camera at waist level as you can see what you have selected without having to reposition the camera.

Overall, the Old Standard has just enough of what made later Rolleiflexes great, while retaining a lot of the original model’s DNA. While I can’t really say that there ever was a “bad” Rollei, some of the later models are so similar to each other, it can be difficult to pick one two things about them that stand out as unique. That’s not true of the Old Standard. If you love pre-war “nickel and leather” German cameras, but want a Twin Lens Reflex camera that’s unlike others out there, the Rolleiflex Old Standard should be right up your alley!

My Results

For the first roll through the Rolleiflex Old Standard, I used a very expired roll of some unknown ORWO film that I had acquired in a box of stuff a while ago. The film had no expiration date and I couldn’t even tell exactly what kind of film it was, or what speed it was. Making an educated guess, I assumed it was originally an ISO 50 speed film and I gave it one stop of overexposure and shot it like a 25 speed film. The first 5 images below are from that film.

Several months later, I decided to give the camera another roll, this time with less expired Ilford FP4 125 film that I shot like a 100 speed film, and the last 5 images below are from that roll.

My first roll using the ORWO film didn’t turn out too good. It would appear that the film was stored poorly as it lost quite a bit of sensitivity and had deterioration near the edges. What little I could see in the center was decent however, and gave me hope for a better roll.

Sadly, it would take me over half a year to get around to shooting a second roll through the Old Standard, but when I did, I chose another roll of expired film, this time some Ilford that I had previously shot in another camera and knew would turn out OK.

It’s clear from these images to see why the Rolleiflex was such a popular camera. Although the Zeiss had been making Tessar lenses since the very early 20th century, by the time this camera was made, it was a staple of medium format and 35mm cameras. The images have a bit of a glow to them that I attribute to the uncoated lens and a very slight amount of internal haze.

For as great of a reputation as Zeiss lenses have, I’ve found them to be especially prone to haze over the years and although this example wasn’t in too bad of a shape it does give the images somewhat of an ethereal look to them. But frankly, that’s fine with me. I didn’t expect these images to be “digital” or even resemble that of more modern TLRs like the Minolta Autocord or Yashica D.

I enjoyed my time with the Old Standard, and found it fun to be able to step back in time and experience a very popular camera from 80+ years ago. The viewfinder was very dark and hard to see in all but bright outdoor light, so if I were to use this camera regularly, I would definitely need to replace the mirror and the ground glass. I didn’t try any color film in it, but based on my experience with other 1930s cameras with uncoated optics, I would expect there to be a softness to the color and the amount of lens haze likely would have rendered the images flat. Black and white film is definitely the way to go with this camera.

This camera did not work and was in terrible shape when I got it, so the fact that I got anything out of it at all is great. The viewfinder is hard to see through, and the combined shutter cocking lever and shutter release did take some getting used to. Overall, my experience with the Old Standard was positive. This is a historically significant camera that with it’s nickel and leather cosmetics looks quite a bit different from every Rollei that would follow it. The images have a distinctive vintage “glow” to them, and although I wouldn’t bet my livelihood on this camera, I have no doubt in my mind that it still can’t provide many more years of use.

You don’t need me to tell you whether you should buy a Rolleiflex or not. This camera’s reputation precedes it, but I can tell you that of all the Rolleis from the 50s and 60s that occupy spots on the shelves of camera collectors world wide, this early model is absolutely worthy of the name “Rolleiflex”.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Rolleiflex_old_standard_model

http://www.theonlinedarkroom.com/2016/12/rolleiflex-old-standard-review.html

https://www.philippemartin.es/new-life/rolleiflex-old-standard

http://www.rolleiclub.com/thedarkroom/?p=3076

http://www.vintagephotographic.uk/franke-heidecke-standard-rolleiflex-k2-6rf-621-1933/

https://filmosaur.wordpress.com/2013/07/10/meet-the-camera-rolleiflex-old-standard-model-621/

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/rolleiflex-old-standard.252729/

This is a superb article – the restoration sequence and photos are invaluable. The quality of the mages made with your Old Standard could lead one to shoot, say, a series on cemetery monuments, or carousel horses, or architectural details on 19th c buildings. Many thanks for this post, Mike.

Thanks Roger! One of my favorite photographic subjects are cemeteries, and dilapidated buildings. Living in the far south Chicago suburbs, on the edge of “farmland” theres a lot of old abandoned houses, barns, and old cemeteries that make for good subjects! I really do like the Old Standard. It doesn’t make crystal clear, razor sharp, perfect photos like later Rolleis, but that’s OK. I think it’s images have more character.

Great post! Mine is all there except for one side panel and plvot rod of the hood. Robert Capa and Gerda Taro shot some of their great Spanish Civil War stuff with one of these “Old Standards”, apparently. Thanks for what you are doing.

Any ideas on where to find the flip up focus magnifier ? The one on the camera I acquired is missing. My father in law brought the camera back after WW2 and since his grandson is getting married in a few months I thought it would be a nice gesture to take some wedding photos with his grandfathers camera. He served with the 442 Nisei Battalion is Italy.

Garland, I wish I could help you, but replacement parts from these old cameras are almost always taken from other parts cameras. Your best bet would be to locate another Rollei of similar age and try to salvage the parts from it. If you’re not concerned with cosmetics and just want something functional, any small magnifying glass would work. Perhaps for the sake of shooting that wedding, you could just locate a small magnifying glass and find a way to temporarily hold it into position, perhaps with a rubber band or something. It would look goofy, but would work fine.

Strange to read an article about Rollei and not include the Rolleidoscop. The Rolleidoscop was the second camera the company built – it was the roll film version of the Heidoscop. The Rolleidoscop was offered in two format versions – one that took 120 film, and one that took 127 film, sometimes named the “Baby Rolleidoscop”.

Awesome page thank you! Very helpful to dive inside my own 620.