Nikon is the brand of camera I am most fond of, and the one I regularly shoot in my everyday life. So, it might seem peculiar to hear that Nikon cameras are my least favorite to write reviews for. There are a couple of reasons for this, one is that my closeness to the brand causes me to struggle to find the words to review Nikon cameras in an unbiased and informative manner. Another reason is simply that so many other people have reviewed Nikon products over the years, I find it difficult to add anything that hasn’t already been said countless times.

Nikon is the brand of camera I am most fond of, and the one I regularly shoot in my everyday life. So, it might seem peculiar to hear that Nikon cameras are my least favorite to write reviews for. There are a couple of reasons for this, one is that my closeness to the brand causes me to struggle to find the words to review Nikon cameras in an unbiased and informative manner. Another reason is simply that so many other people have reviewed Nikon products over the years, I find it difficult to add anything that hasn’t already been said countless times.

When I do manage to find the words to review a Nikon product, it’s been one of their lesser loved models like the Nikon EM from 1979 or the N80 from 2000. Everyone already knows how great the pro-level Nikon F1-6s or the popular pro-sumer models like the FM2 and FE2 are, yet the EM and N80 don’t get near as much time in the limelight, so I felt compelled to share my thoughts on those models.

As my Nikon collection grows, I find that I have more and more models that are worthy of review, but what do I say? And how? I already mentioned I struggle writing full reviews for Nikon cameras, so I thought I should pick three less common models and do a single review of all three. I’ve done ‘three-fer’ reviews in the past so I thought it might be more fun (and easier) to write one review about three different Nikons from three different decades, the 70s, 80s, and the 90s.

My Results

Unlike other camera reviews where I show a gallery of images shot with each respective camera at the end of each review, I am doing something different here and putting the gallery at the beginning.

One of the hallmark features of every Nikon SLR since the first Nikon F in 1959, is that Nikon has continued to use the same Nikon F-mount the entire time. Sure, there have been revisions to the mount that have confusing names like Non-Ai, Ai, Ai-S, AF, and AF-S, and not every lens is fully interchangeable with every body, but they usually can be used. I won’t get into the nuances of which lenses are compatible with which bodies as there are already many excellent articles written by other people which explain this. Ken Rockwell has one of the best guides with visual explanations, so if you’d like to know more, I recommend reading his article.

Since the lens usually has a greater impact on the outcome of a photograph than the body, each of the three models here could have shot any of the images below. In fact, I’d argue that since you could swap most of the lenses with any Nikon body in my collection, the optical quality of each image would be identical, regardless of which body that lens was attached to.

Nikon has made some of the best lenses of the 20th and 21st centuries. They perfected the optical formulas of their primes over half a century ago. Using a 50mm lens from the 1960s is not going to have much of a noticeable difference in sharpness, color accuracy, vignetting, chromatic aberration, or any other lens characteristic than had you used a brand new 50mm made yesterday.

Whether you prefer an all mechanical Nikon F from the 60s, an aperture priority ELW from the 70s, an auto focus N2020 from the 80s, or a fully automatic N90s from the 90s, the reason you might choose one over the other is not going to be because of the quality of images you can make with them, but more for the features, design, and layout of the body itself.

So with that in mind, each of the images below could have been shot with any of the 3 cameras here. I honestly can’t even remember which shots were done with which. I could even sneak in some that weren’t shot with a Nikon in this review and you’d likely never know. But I promise you, it doesn’t matter which body shot which image, you’d never know the difference.

The 70s – Nikomat ELW (1976)

This is a Nikomat ELW 35mm SLR camera sold between the years 1976 and 1977. The “Nikomat” name signifies this was a Japanese market camera sold outside of the United States. Examples sold here in America are identical in every way, except they were given the name “Nikkormat”. The ELW was the black version of the earlier EL model and added support for the AW-1 automatic winder which was capable of up to 2 frames per second, otherwise the ELW and EL are identical models.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Nikon F-Mount Bayonet Mount

Lenses: Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 + many others

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Vertical Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 4 – 1/1000 seconds, stepless

Speeds (Mechanical): 1/90

Exposure Meter: Center-Weighted metered TTL CdS meter

Battery: 6V PX28 alkaline or silver-oxide

Flash Mount: Hotshoe plus PC X-sync port

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_elw.pdf

My Thoughts

I picked up a Nikon EL2 in the spring of 2014 in what started out as general curiosity of what it might be like to shoot film in the digital age. At that time, I knew very little about Nikon’s film SLRs and only chose the EL2 because it was in my price range and that I knew I could use it’s lens on my Nikon DSLR.

I knew nothing about camera repair, or Sunny 16, or anything about film for that matter. Sure, I had a few film cameras as a kid, but nothing even remotely serious, and nothing that could prepare me for what was to come.

That EL2 was in good operating shape, but was cosmetically very rough. As a result, I ended up selling it in an effort to get a better example of a working film Nikon SLR. About a year later, I came across another EL2 in equally bad condition, and I didn’t even bother putting any film through it as the viewfinder was messed up pretty badly.

As my Nikon collection grew, I always had it in the back of my mind to get another EL2. There’s really no logical reasoning behind it. There’s nothing truly spectacular about the EL2 that makes it better than other Nikons. Its like an FE in the body of a Nikkormat (actually, that’s exactly what it is). Still, I wanted another. The bargain gods had different plans however. To date, I still haven’t located a good enough condition EL2 in my price range, but I did stumble upon this Nikomat ELW. The EL was the predecessor to the EL2 and was Nikon’s first camera both with an electronic shutter and auto exposure. The ELW is just the black version of the EL. The “W” in the model name is to signify that Nikon had added a provision for the AW-1 auto winder, which the original EL lacked.

So here I am with a slightly newer version of Nikon’s first electronic camera. Two things that have remained true ever since Nippon Kogaku’s first rangefinder lenses, all the way to their current generation of digital cameras is that they take their time with new technologies, but when they do finally get around to it, they don’t mess around.

Note: For the remainder of this article, I will refer to Nippon Kogaku as “Nikon” even though they did not officially become known as the Nikon Corporation until 1988.

Without getting too much into a history lesson of Nikon SLRs, their first models were top of the line, fully decked out, very expensive models, aimed at the professional market. If you were a pro photographer in the 1960s, its likely you shot with a Nikon.

Despite their huge success in this market, Nikon realized there was a need for a more consumer friendly (and priced) model, so in 1965, they released a new line of cameras known as the Nikomat in Japan, and Nikkormat everywhere else. These cameras were simpler and less expensive than their big brothers, but were built to the same high quality standards, and accepted the same lenses as the Nikon F.

The Nikkormat line sold very well and was a popular choice among advanced amateur photographers well into the 70s, even though there were many other smaller, and less expensive offerings by other makers. In fact, many pro photographers would often buy a Nikkormat as a “backup” camera in the event something went wrong with their primary camera.

The Good

One of the best features of the Nikomat ELW is true of all Nikkormat/Nikomats, and that is of it’s robustness. This is a very well made, large, and heavy camera that takes a beating and keeps on ticking. Many Nikkormats are still completely functional today, nearly 50 years after they were built. Despite it’s role as a “lesser” camera, Nikon did not skimp on quality. They did not settle for a shutter made of cloth. All Nikkormats have vertically traveling metal blade shutters that were very accurate and in the case of the ELW, were stepless, meaning if the meter detected that a shutter speed of 1/612th of a second was needed, that’s what you’d get.

Other than small parts like the tip of the wind and self timer levers, there’s almost no plastic on this camera. It’s all metal. The ring around the shutter speed selector and film speed dial are made of metal with deep knurls that are robust and easy to turn.

I could talk about how well the ELW was made all day, but the signature feature was it’s electronic shutter and aperture priority auto exposure system. Although auto exposure was hardly a new feature in 1972 when the first EL model was made, it was a pretty big deal for Nikon. Again, they weren’t ones to rush to market with a new feature, so by the time they were ready to venture into the world of an electronic shutter with auto exposure, you bet they made sure it worked properly.

And work it did. The design and feature set of the first EL/ELW extended to the Nikon EL2 in 1977, and the Nikon FE in 1978. The meter on the ELW is as good as any auto exposure camera made in the decades following it’s release. Combined with the heft of the Nikkormat body, the ELW is a unique classic camera that has the feel and build quality of the 60s, but with the electronic advancements of the 80s.

In terms of features, the ELW has most of what you’d want in a mid-70s SLR. It has a hot shoe and a PC-sync port for most any kind of flash you’d want to use. The shutter is flash synced at 1/125 seconds, and has manually selectable shutter speeds from 4 seconds to 1/1000th of a second. In the event the battery dies, the shutter will fire at 1/90th of a second meaning a photographer is not left with a dead camera in the event the battery fails. There is a depth of field preview button and mirror lockup (more on this later) which was something that was quickly disappearing from consumer SLRs in the mid 70s. The back of the camera features a threaded eye piece which allows various eye pieces and diopters to be used, and it has a battery check light to confirm the battery is fresh.

The viewfinder in the ELW is a little darker than those found in modern SLRs, but it was certainly on par with others from the day. Curiously, many articles I’ve read (including pages 8 and 27 of the ELW’s user’s manual) state that the camera comes with Nikon’s new Type K focusing screen which has a split image rangefinder in the center of the screen. My particular example lacks a Type K screen, and instead has an earlier screen with only a microprism circle in the center. I am not sure if the switch to a Type K screen was a mid-model switch, or if my particular example was modified by a previous owner. In either case, mine doesn’t have it.

My favorite feature of the whole EL series is the shutter speed scale inside of the viewfinder. The scale is completely analog showing both a black and a green needle next to a chart showing a scale from 4 seconds to 1/1000. There is also an “A” at the top of the scale indicating Auto Exposure mode, and a “B” at the bottom, indicating Bulb mode.

The green needle indicates what you have selected using the shutter speed dial on top of the camera. If the camera is in Auto mode, the green needle points to “A”. If you have selected any of the manual speeds, the green needle points to your selected speed. The black needle is linked to the meter of the camera and works in both Auto and manual modes. The meter is powered on any time the film rewind lever is pulled back to the first indent. At that point, the needle continually moves depending on the amount of light detected by the meter. In Auto mode, this needle is purely informational only. As with any camera, shutter speeds slower than 1/60 should be stabilized to guarantee that there will be no motion blur in your shots.

In any of the manual modes, the green needle points to whatever speed you’ve selected, and the goal should be to get the black needle to match up with the green needle. This acts like a hybrid “match needle” system common on metered non-AE models like the Nikkormat FT series. If the black needle is too far off from the green needle, then that means you are going to over or underexpose your shot.

This metering scale was so well designed and easy to use, that Nikon continued using it on the Nikon FE and FE2. If you consider the first EL was produced in 1972, and the FE2 was made until 1987, that’s a total of 15 years that this system was in use.

The Not So Good

Despite Nikon’s best effort to work out the gremlins of an electronic shutter with auto exposure, they weren’t perfect. Although the model in my collection works flawlessly, I’ve heard rumors that early ELs were plagued with reliability issues. The EL has a very complex design and as a result many repair shops of the era would not repair them when they stopped working. Repairing a broken EL is not an easy task and since Nikon won’t work on them anymore, if you were to find one today that didn’t work, your chances of restoring it are slim to none. Although I cannot prove this, since the ELW came out in 1976, four years after the original EL, it’s plausible Nikon worked out many of the bugs, and these later models could be more reliable. This is just speculation on my part, though.

Another gotcha of the EL and ELW is that these were the last models released by Nikon prior to their switch to Ai (or Auto-Indexing lenses). Non-Ai Nikkor lenses are the ones that depend on those external “rabbit ears” common on many Nikon lenses of the era. Non-Ai Nikon bodies relied on an external coupling pin to engage those rabbit ears on the lens so that the camera could detect which aperture setting the photographer had chosen. The image to the right shows the coupling pin engaged with the “rabbit ears” of the lens. While Non-Ai lenses aren’t inherently bad, and still offer the ability of open aperture automatic exposure, they are more difficult to mount and do not allow for aperture readouts in the viewfinder (for cameras that support it).

You can also use Ai and Ai-S lenses on the EL and ELW, as long as the rabbit ears are still there. The camera functions exactly the same whether you have a Non-Ai, Ai, or Ai-S lens attached. I like this aspect of the EL and ELW as Non-Ai lenses often go for less in the used market, so the ability to natively support those lenses on the EL and ELW is a good thing.

The model that replaced the EL and ELW was the EL2 which added support for Ai lenses while maintaining backwards compatibility by way of an Ai pin that can be folded out of the way to accommodate Non-Ai lenses. While many people consider the EL2 to be superior to this original model because of this folding pin, I actually think the original model is better because it can meter with an open aperture using both Non-Ai and Ai lenses since Ai lenses still have the rabbit years. With the EL2, you can only meter with Non-Ai leses with the lens manually stopped down.

A neither good nor bad feature of the ELW is it’s battery compartment. Nikon wisely chose to support the 6v PX28 battery as opposed to common mercury batteries of the day. This means that the camera’s electronics are designed for 1.5v batteries which are easy to find today, and are less likely to leak unlike other mercury batteries. The strange thing however, is in the location of the battery compartment. The EL, ELW, and the later EL2 are the only cameras I’ve ever seen that have the battery located INSIDE of the mirror box!

I mentioned earlier that a ‘pro’ of this model is that it has a mirror lockup feature, but that was more out of necessity rather than to allow for vibration free long exposures. You need to lock the mirror in it’s ‘up’ position in order to gain access to the battery which is beneath a flap under the mirror.

Looking at the images to the left and right, you can see that with the mirror in the up position, there is a little door at the bottom of the mirror box. You must stick your finger in there and slide the door to the left in order to release it’s lock. When the door is opened, it pops up, revealing a small compartment for the PX28 battery. It is a very tight fit and definitely one of my least favorite aspects of this camera as you have to be very careful not to accidentally whack the mirror or the back of the shutter which is exposed when you do this.

I read somewhere that Nikon thought that by placing the battery in this location, the battery was better protected from external damage and moisture, and also eliminated the need to increase the size of the camera to accommodate a new battery compartment elsewhere on the camera. Regardless of the reason, after the EL2, they never put a battery in this location again.

Conclusion

I don’t believe that anything mentioned above is a big enough con not to recommend the EL or ELW. The EL2 is probably a better choice for someone who doesn’t have any Non-Ai lenses, but since the EL and ELW can meter with the lens wide open using both Non-Ai and Ai lenses, I feel the original model is better for those with both types of lenses in their collection.

Even though I have more feature-rich Nikon bodies, and I tend to prefer the smaller size of later Nikons, this ELW remains one of my favorite Nikon bodies to shoot with. The camera itself is gorgeous, the viewfinder is nicely designed, the meter is spot on, the camera has that nice and heavy all metal feel reminiscent of older cameras, and of course, it takes all of my Nikkor lenses!

When people talk about the most popular Nikon SLRs, the EL-series cameras are rarely mentioned, but I think they’re all great cameras. Assuming you can locate one in good working order, I absolutely recommend adding an EL-series Nikon to your collection.

The 80s – Nikon N2020 (1986)

This is a Nikon N2020 35mm SLR camera sold in North America between the years 1986 and 1990. In other countries, it was sold as the F-501, but was otherwise exactly the same. It was Nikon’s first mass produced auto focus camera and was marketed as a high end model with all of the bells and whistles an advanced camera from the mid 1980s would offer. It’s place in Nikon’s product family was immediately below the professional F3HP. The N2020 was a very successful model, setting the stage for a high end “pro-sumer” lineup of cameras which continues to this very day.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Nikon F-Mount Bayonet Mount

Lenses: Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 + many others

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Vertical Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/2000 seconds, stepless

Exposure Meter: Center-Weighted and Spot metered TTL Silicon Photo Diode meter

Battery: 4 x AAA alkaline, lithium, or rechargeable (optional AA battery holder was available)

Flash Mount: Hotshoe

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_n2020_af.pdf

My Thoughts

I have a confession. Of all the Nikons in this review, or my entire collection for that matter, the N2020 is the one I had no intention of ever owning. In fact, this camera almost wound up in the garbage bin when I first acquired it.

For a long time, my interest in film cameras omitted anything from the auto focus era of the 1980s. I slowly grew fond of the more advanced models from the late 90s and early 2000s, but there was a gap from about 1985 to the late 90s where I simply had no interest.

I have come across two different N2020s and an N2000 in my time collecting. The N2000 is essentially the same camera, just without the auto focus system. They were all given to me in various boxes o’ junk. At first, I dismissed them as throwaway cameras in my quest to see what else was in the box, but after stumbling upon some article referencing the N2020 as Nikon’s first auto focus SLR, I thought it was worth a second look.

Upon holding the N2020, it certainly feels light weight, as was typical of most cameras from 1986, but there was also a certain familiarity in the design that later plastic Nikons lacked. For one, this model still had the original non-italicized Nikon logo that first appeared in 1971 on the F2. It also had a traditional looking shutter speed dial and rewind knob on the top plate of the camera, exactly where both would have been located on nearly every Nikon made before it.

The N2020 is a good looking camera and predated the bubble-like rounded edged SLRs that would follow it. It had a relatively squared off body, not unlike the Nikon FE2 or FM2 that would have still been for sale at the same time this N2020 was first released. The right front side of the camera had the beginnings of a small hand grip, like the one on the FA. In fact, other than the lack of a wind lever, the top of the camera could easily be mistaken for a model made half a decade earlier.

Although the camera is loaded with plastic, there is a certain quality to it. Later in this review you’ll read how the thin rubber backing on the film door of the N90s is easily scratched off and almost always turns into sticky goo, yet, none of the leatherette or synthetic body covering of the N2020 exhibited such behavior. In some ways, the design choices made on the N2020 stand the test of time better than cameras like the N90s that came nearly a decade later.

As was typical of Nikon’s marketing strategy, the Nikon N2020 is the North American name of the camera. Elsewhere in the world, it was known as the F-501. The manual focus only N2000 was known as the F-301.

With the N2020’s historical significance as Nikon’s first auto focus SLR, its semi-retro appearance, and cosmetics that hold up to the rigors of time, I decided the N2020 shouldn’t be relegated to a box o’ junk. No, it was a model worth my time and effort to use and review.

The Good

The N2020 was definitely a transitional model for the designers at Nikon. Although Nikon had been using a red stripe on the hand grip of their SLRs since the F3 from 1980, the N2020 was the first one to make the stripe horizontal, near the top of the grip which is exactly where it still is today.

It was the last model to feature the non-italicized Nikon logo, the last model with a traditional shutter speed dial, and the last consumer level Nikon with a manual rewind knob. All future models would employ some type of revised control layout with an auto rewind feature. While these omissions might have been seen as representative of a low-spec model in 1986, I found them to be a welcome feature of a semi modern auto focus body, with familiar controls of the manual focus models of the past.

The viewfinder is large and bright with visible shutter speeds lit up on the right side of the display. In any of the auto exposure modes, the camera will indicate it’s selected shutter speed, but in manual mode, it will indicate both your selected speed and the one the camera recommends you use. It works similarly to the twin green and black “match” needles in the Nikomat ELW reviewed above. This is quite a useful feature when shooting Sunny 16 so that you can see if your estimates agree with the camera’s.

At the bottom of the viewfinder is one of 4 LED indicators. A green circle means that correct focus has been achieved. Two red left or right arrows indicate that the camera doesn’t think you have correct focus, and a red X indicates that the camera cannot detect focus at all either due to low light, or that you are in one of the situations the AF sensor can’t detect.

Nikon’s use of plastic and other lightweight materials made for a very lightweight camera. The N2020 weighs a mere 644 grams with no lens or film, but with batteries installed. This is more than 25% lighter than the N90s reviewed below. Despite these weight reducing materials, the N2020 never feels cheaply made. It has the same stainless steel lens mount featured on nearly every Nikon SLR ever made. It does not creak or groan in your hands, and while I wouldn’t recommend testing this, it gives the illusion that it could survive a fall of several feel without any ill effect.

This lightweight and compact design is a welcome exception to the large and bulbous SLRs of the late 80s and 90s. Hanging this camera from your neck while taking an all day trip to the zoo would likely cause you far less fatigue than the other two models in this article.

It might be easy to dismiss the N2020 as a rudimentary auto focus camera that lacks the bells and whistles of a modern SLR, but there are a few surprising features that might seem appealing to a current collector wanting to add a semi-classic model to your collection.

-

The Nikon N2020 was one of the last consumer level Nikons to offer an interchangeable focus screen. Unlike most every other consumer level SLR, the N2020 supports interchangeable focus screens. The included screen is a Type B screen, but both the Type E and Type J can also be used.

- A quick load system makes film loading a snap. Simply install a new cassette on the supply side, extend the leader to a red mark in the film compartment, and close the door. The camera will do the rest.

- A proper +2 / -2 EV compensation dial, just like the classic Nikons that came before it.

- A manual film speed dial. Unlike some fully automatic 35mm cameras of the 80s, you can override the DX film speed or use non DX encoded film. Some fully automatic point and shoot cameras from the 80s would only work with DX encoded film and if the type of film you were using was outside of the range of accepted speeds, the camera would often default to something like ISO 100 which wouldn’t always be correct. If you want to manually select your film speed, there is dial which you can select any speed from ISO 12 to 3200.

- TTL flash support. Although TTL flashes aren’t exactly rocket science today, in 1986 when this camera was first introduced, not every camera supported it. The use of non-TTL flashes was still common, and when coupled with a flash that supported it, the camera could do a much better job of measuring exposure with a flash attached. I can use my SB-600 speedlight from my D7000 DSLR on this camera in full TTL flash mode.

- Program and Hi-speed Program modes. This isn’t something I think would have been used a lot, but its an interesting workaround for instances where a photographer wants to emphasize a faster shutter speed while still using a full program mode. When the camera is in regular P mode (or Dual and using a normal lens) the camera selects a safe shutter speed and aperture combination which will achieve correct exposure. In P HI mode, the camera will select the combination of largest aperture and fastest possible shutter speed to minimize motion blur for fast motion speeds. Most modern cameras don’t allow for any type of tweak to the shutter speed when in Program mode.

The Not So Good

The N2020 was Nikon’s first SLR built for auto focus. I fully expect some Nikon-historian to contact me and remind me that there was an auto focus version of the F3 released before this, but that was a very rare variant that is not very common, plus it required special auto focus lenses that only worked on that model, so my comment that the N2020 was the first Nikon designed specifically for auto focus is still true.

Anytime you have a new technology, you can’t expect it to be perfect, and that certainly holds true here. The auto focus system in the N2020 was very primitive by today’s standards. It was slow and indecisive, didn’t work very well in low light, in scenes with a lot of motion, in a lot of contrast, or with lots of horizontal lines, plus it was loud.

If the auto focus system seems to be getting in your way, there is a manual focus switch on the front of the camera that disables the auto focus system. The viewfinder still has a focus confirmation light that will help you get correct focus manually, but that’s limited to the same types of scenes as in auto focus mode, meaning it won’t be very helpful in low light or with a moving subject.

Even louder than the auto focus motor is the film advance motor. After each shot, the camera automatically advances the film to the next frame using what sounds like the motor from a high speed electric drill. This was definitely not a camera you’d want to shoot with in a situation where you needed to be discreet. I can imagine the stink eye some parents might have been given trying to use this camera at a their children’s dance recital due to the cacophony of robotic groans that this camera makes every time you take a picture.

I shot my entire test roll using a Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 AF lens and found the auto focus to be quite slow. In many situations the camera would pause while searching for the correct focus. It would eventually find it, but there was a significant delay from when I would half press the shutter to when the camera would get the focus right. This seemed to happen both while shooting in brightly lit outdoor scenes, and indoors. I cannot for sure say whether this is normal behavior of the N2020 as I couldn’t find any mention of it in any review I’ve found online, or if this is just a flaw that has developed with my example in the 30+ years since it was made.

Still, it works and does a good enough job under optimal conditions that I imagine a lot of people were pretty impressed with what this camera could do upon it’s release. The July 1986 issue of Popular Photography has a review for the N2020 and the author concludes the article saying:

Like many photographers, I resisted AF as an unwanted encumbrance. But, after working with the N2020, and seeing the results, I’ve come to recognize AF as an effective aid in many shooting situations.

The only other major issue that I’ve seen with this camera is that for some reason, this model seems to be especially prone to corroded battery compartments. While any camera ever made could have a corroded battery compartment if a previous user left a battery installed for too long, all 3 of these cameras I’ve come across all had various issues with the battery compartment.

When the battery compartment becomes corroded, the electronics stop working and the camera does not function. Looking at current auctions for N2020s and N2000s on eBay, many of them mention issues with the battery compartment and non working electronics, which suggests that the issue extends beyond my three. I have picked up many electronic cameras in my day, and I’ve never seen a model so consistently have an issue with corroded battery compartments. I don’t know if Nikon used a different kind of metal for the electrical contacts that was more prone to corroding than other models, or if the AAA batteries typically used in the N2020 were more likely to leak, or if because the N2020 was aimed at a less knowledgeable user, that the chances of leaving batteries installed in a camera for too long was more common.

Sadly, of the 3 examples I’ve had, I was only able to repair one of them, and in order to do that, I had to swap parts from the one with the best looking battery compartment to the best body. Look at the image to the left and you can see the difference between a good battery compartment, versus one that is corroded.

I recommend using caution if you attempt to pick one of these up on the used market. You’ll want to make sure that the seller says the camera is in good working order, as “untested” N2020s could likely mean that they may have the same issue. The N2020 is a completely electronic camera, and unlike the mechanical Nikons of the past, the shutter will not function without power, not even at a single speed.

I could probably lament about a few features that are missing from the N2020 like a cable shutter release, mirror lockup, or a 1/250 second flash sync speed, but these aren’t features that the target audience that this camera was designed for, would have wanted.

Conclusion

The Nikon N2020 is quite the surprise of a camera. This is a model I initially discarded as an uninteresting relic of the 80s, but it turned out to be both a historically significant and well featured camera that I enjoyed using. I found that while shooting with the camera, I enjoyed Aperture Priority “Av” mode the best. I am not sure if there is a defect in my model, but I found that when using any of the full Program modes, there was an additional delay between pressing the shutter release and the shutter firing. This delay was not present in either Av or manual modes.

The N2020 has some familiar design elements linking it to Nikon’s classic models of the past, while offering a glimpse of some modern technologies like auto focus, quick film loading, and TTL flash support. Despite it being a lightweight camera made with a lot of plastic, it stayed true to Nikon’s reputation as a maker of quality built cameras. Most surviving models found today don’t exhibit common ailments like peeling rubber, brassing, or broken film doors. In my opinion, this would be the best looking auto focus model in Nikon’s lineup until the F100 and N80 were released in 1999 and 2000 respectively.

It certainly is not a perfect model, and the auto focus system isn’t anywhere near as good as a modern camera, but something I speak about in many of my reviews is using a camera to it’s strengths. With the N2020, this means taking it outdoors when the lighting is good and shooting things that aren’t zooming about. If you want interior shots of children, you could do better picking a different model, but when you do use the N2020 to it’s strengths, you will be rewarded with some excellent photos.

Edit: I wrote this part of the review before I saw the scans from my first roll through the N2020. In the gallery above, the shot of the child playing with the wooden toy train was taken with this N2020 and the auto focus system certainly handled this situation well.

The biggest condition issue is with the battery compartment, so if you are looking to add one to your collection, that is the first thing you’ll want to confirm before buying. If you are feeling brave, you could take a chance on a few of these on eBay as they often sell for very little.

The 90s – Nikon N90s (1994)

This is a Nikon N90s 35mm SLR camera sold in North America between the years 1994 and 1999. This camera was sold outside of the United States as the F90X. Other than the names, there were no other differences between an N90s and F90X. Each camera was an improvement of an earlier model, released in 1992, called the N90 and F90. The N90 and N90s were both marketed as high end cameras, immediately below the F4 and F5 in Nikon’s lineup.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Nikon F-Mount Bayonet Mount

Lenses: Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 + many others

Focus: Fixed SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Vertical Metal Blade

Speeds: B, 30 – 1/8000 seconds, stepless

Exposure Meter: 3D Matrix, Center-Weighted and Spot metered

Battery: 2 x 3V CR123A Silver-Oxide or Lithium equivalent, also compatible with MB-16 Battery Pack

Flash Mount: Hotshoe

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_n90s_af.pdf

My Thoughts

I find it easier to review lesser known Nikons for the reasons I already discussed above. One of those ‘lesser known’ Nikons was the N80 which I reviewed earlier this year. I praised the N80 as an advanced and fully automatic Nikon body that offers all of the modern conveniences and excellent ergonomics that we’ve grown accustomed to with modern DSLRs, but in a model that shoots film and allows you manual flexibility if you want it.

The N80 rarely sells for more than a few dollars on the used market, and combined with it’s excellent feature set, could possibly be the best value for a Nikon SLR ever made, with one notable exception, which is that it can’t meter with manual focus lenses. This is a curious omission to the N80’s feature set as there’s no technical reason why this isn’t possible. It’s almost as if Nikon purposely disabled the meter whenever a non Auto-Focus lens is attached. This probably was done as a means to encourage photographers to abandon their older lenses and upgrade (aka spend more money) to newer lenses.

When the N80 was a current model, it was aimed at the middle of the SLR market, and it’s likely that anyone considering buying it new probably had no interest in using manual focus lenses, so I really doubt many people back then missed this feature.

I like manual focus lenses, and I have a ton of them, so losing out on the ability to meter on the N80 was a pretty big downer to me. I read that the next model up in Nikon’s portfolio at the time, the F100, could meter with manual focus lenses, so I began my search for one. As it turned out, more people think like I do, and the F100 is still a pretty desirable body. Good working F100s regularly sell for well over $100 these days for just the body, and while that’s a considerable discount to what it sold for new, it’s still out of the price range I would regularly pay so I looked at what other modern Nikons could also meter with older lenses, and while there are a few of them, the one that kept popping up on my radar was the N90s.

The N90s was the replacement for an earlier model, simply called the N90 which despite the omission of the ‘s’ in the model name, had quite a few differences. The most significant was a completely new auto focus system. Nikon’s earlier auto focus cameras paled in comparison to their competitors, specifically Canon, whose EOS line of auto focus cameras did it better than anyone else at the time. The N90s included a new auto focus engine known as CAM 246. It made significant improvements to the speed and accuracy of the auto focus system, especially with moving subjects.

Other, less significant changes were a slight bump in continuous shooting speed to 4.1 FPS, the ability to manually adjust exposure in steps of 1/3rd EV as opposed to a full EV step, and improved weather sealing.

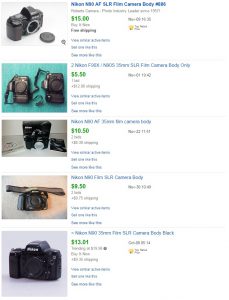

The N90s was known as the F90X overseas and was the predecessor to the F100. It’s original MSRP was over $1000 for the body only when it was released in 1994 and was sold new as recently as 2004. It was marketed as an advanced consumer camera immediately below Nikon’s flagship F4 and F5. The camera sold extremely well over it’s 10 year production run and even remained popular as a bargain film camera into the first few years of the digital age. Although I could not find any indication of production numbers, the vast number of them for sale in the used market suggests that tons were sold. This is great for bargain hunters like myself who want to pick one up for peanuts. In fact, I won’t let you get any farther into this review without declaring that the N90s is without a doubt, the single BEST bargain of any Nikon film SLR made, ever. Look at the prices to the right, this is a $1000 camera selling for as low as $10!

The Good

The N90s was a very high spec camera, and although it was positioned beneath the F4 and F5 in Nikon’s lineup, that wasn’t due to any major shortcomings of the model. Whatever the N90s lacked compared to those top of the line models, it was minor.

It had an all metal chassis surrounded by a weather and dust sealed plastic body to better protect it from the elements. It had a lightning fast shutter with a top speed of 1/8000 seconds and was flash synchronized at an equally fast 1/250 seconds, both speeds of which are still considered state of the art today in 2017. It offered pretty much every shooting mode you could ever want. It had Nikon’s state of the art (for the time) CAM 246 auto focus system which could continuously maintain focus on moving objects making it ideal for fast action like sports photography. It had Nikon’s flagship 3D Matrix exposure system that had an exposure range of EV -1 all the way to EV 21 making it ideal in very low and bright light situations. The list of features of the N90s was quite long, but the one that I was happy to see was that yes, it can spot and center weight meter using manual focus lenses (matrix metering is not supported using manual focus lenses).

The viewfinder has a very modern appearance with a full information LCD display at the bottom of the viewfinder. It’s not quite as informative as a modern DSLR, but it gives you nearly all of the information you could possibly want, including the extremely useful auto focus confirmation light which helps you achieve properly focused shots on manual focus lenses.

For a very detailed review and full list of all of the shooting modes and features of the N90s, Ken Rockwell has an excellent review on his site. I won’t repeat too much of what Ken has already covered, but I’ll keep echoing the same comment I’ve said a couple of times now, the N90s is an amazing camera that can do pretty much anything you could ever want to do with film.

The Not So Good

Frankly, my only complaints about the N90s are cosmetic and highly arbitrary ones that don’t have any impact on the camera’s capabilities. The first is that it was made during the peak of the “plastic fantastic” era which lacked that refined glory of the previous generation’s all metal bodies. It would be another half decade before Nikon would finally find that right balance of plastic, rubber, and metal that looked as good as they functioned.

In fact, one very common problem with the back of the film door was that Nikon originally used a very thin rubberized coating on the plastic door to improve grippiness, but whatever type of rubber-like material they used, did not hold up well. Almost every copy of the N90s you find for sale has this rubber coating partially peeling off, and what remains is a sticky mess. There is no way to clean the stickiness off the door, other than to remove the coating altogether. I’ve read suggestions on various forums saying the only good way to improve the appearance of the back of the camera is to remove the door from the camera, and use some type of product to chemically remove the rubber. I would be very careful if you were to try this, as plastic has a bad habit of not reacting well to some harsh chemicals. Make sure you have the door removed from the camera before attempting this, and at least have it in the back of your mind that you could etch or discolor the plastic in the process.

Of the three cameras reviewed in this article, the N90s is my least favorite looking model. It’s large dimensions don’t attribute to a compact or easily portable SLR. Not only is the N90s the largest camera here, it’s also the heaviest. Heavier even, than the all metal Nikomat ELW from 1976.

I used a kitchen scale and measured all 3 cameras in this article without any lenses, film, or accessories attached, but with batteries installed. The weights are listed below.

- Nikomat ELW – 778 grams

- Nikon N2020 – 644 grams

- Nikon N90s – 882 grams

To be fair though, the weight is largely due to the solid metal body that lurks beneath all that plastic. Don’t let all that plastic fool you, the N90s is a very well built camera that can take a beating and keep on keepin’ on. It’s just really heavy!

Conclusion

The N90s might be the ugly duckling of the Nikon lineup, but it is one hell of a great camera. The list of features and advanced specifications make for an extremely capable camera in any shooting situation. Many of the camera’s features like the 1/8000 sec top shutter speed and the 3D Matrix auto exposure system are still status quo features for modern DSLRs today.

For those of you who aren’t interested in modern amenities like auto focus or auto anything, the camera supports nearly every possible manual mode you could want. You could be out shooting fully manual using this camera and halfway through the roll, put it back into full auto mode and hand it to someone who had never used a film camera before, and know that they’d get great shots from it. For those of you with spouses or significant others who don’t appreciate your vintage film hobby, this is a huge benefit in maintaining a level of peace when you reach for a film camera instead of a compact digital camera for your next family trip to the zoo!

While I won’t always reach for the N90s as my go to Nikon, it has nothing to do with the capability of the camera. If anything, that’s probably the one knock to it. An advanced camera like the N90s isn’t appealing to people who want a truly vintage camera experience, and anyone looking for a modern everyday camera, likely will reach for something digital instead. Still, that doesn’t mean that this model isn’t deserving to be included in your collection. For the insanely low prices they sell for, there’s really no reason not to have one!

Epilogue

It should come as no surprise that when you have a company that has been making cameras for as long and as successfully as Nikon has, that a few models get forgotten by history. In their day, certainly each of these models generated excitement in the photographic community, but their legacies have turned out to be less spectacular than other models.

For as much as I really would love to add a high-dollar Nikon SLR like an F3HP or F100 to my collection, when I pick up models like the ELW, the N2020, or the N90s, its easy to come to the conclusion that I already have the perfect Nikon. Each of these three models represent 3 different eras of Nikon SLRs and since the lenses in my collection are interchangeable between each of these 3, I have pretty much all that anyone could want. Of course, I’d be naive to think that another won’t end up in my collection someday, I’ll at least know that whenever I want to actually shoot some film, I have a heck of an awesome selection of bodies to choose from!

Additional Resources

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/nikkormat/elseries/elw/index.htm

http://photo-utopia.blogspot.com/2013/08/nikkormat-el.html

http://www.thorleyphotographics.com

http://www.photographic-hardware.info/nikon_manual_focus_slr_film_cameras/nikkormat_el_camera.htm

https://manondamoon.com/2017/01/30/a-camera-the-nikon-f-501-af/ (Interestingly, this review of the Nikon F-501 was posted the same exact day as this review!)

http://www.thephoblographer.com/2016/09/30/vintage-camera-review-nikon-n2020/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nikon_F-501

http://www.jayknightlife.com/2014/05/retro-review-nikon-n2020-for.html

http://filmphotographyproject.com/content/reviews/2011/11/fpp-review-nikon-n90s

http://robdphotos.blogspot.com/2010/07/nikon-f90xn90s-review.html

Very, very helpful and enjoyable review. I look forward to the next. thank you.

The other reason for an F100 commanding more money than the F90x is that the F100 is capable of working with optical vibration reduction lenses (VR)

I have an N90 and an N90s. I paid $500 used for the N90 in the mid 1990’s. It is amazing that you can buy these for practically nothing. The N8008 is also dirt cheap and lighter, good with manual focus lenses to get the good bright viewfinder, focus confirm and accurate metering. Just rub off the sticky rubber on the N90 with your thumbs and don’t give it a second thought. These things are bullet proof and have great viewfinders and a strong focus motor. Great cameras for anyone wanting to shoot B&W and not have to deal with the issues of refurbishing an older body and the electronics are first class.

Submitted for your approval, a tale from the 1960’s. My first 35mm SLR camera was a Canon FP with a never-did-work-well 50mm f/1.8 Canon FL lens. I’d been using 35mm rangefinder cameras for a while, but there was the attraction of using longer-than-135mm lenses on a 35mm SLR that I coudln’t ignore.

I gave the Canon FP to a ex-New Yorker college acquaintance and went looking for a (somewhat) affordable 35mm SLR. In time, I decided upon a Nikkormat FTN, since the Nikon F in basic of Photomic finder version was too expensive. I started off with Vivitar or Soligor lenses, since Nikkors were also out of reach, though I did buy a 35mm f/2 Nikkor as a “wide/normal” substitute for the usual 50mm lens. (I felt that a 55mm Micro-Nikkor was a more useful future purchase.)

The Nikkormat compared favorably with the Canon FT-QL and Minolta SRT-101 contemporaries, and was built like a tank, for Nikon F users as a “weekend” camera. I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d just missed the “set the maximum

aperture number opposite the film speed” shuffle of the previous Nikkormat FT. This one was the “set the lens to f/5.6, move the metering prong to the latching position, attach the lens, then “open and close it down” for meter coupling” wrist action. It went to Japan in the Summer of 1970 and into the succeeding decades, to be finally superseded by the Nikon FM/FM-2 series. I eventually bought a Nikon F-2, but that was for “lab work.”

As for the “automatic 35mm SLR” years, started by the Konica Autoreflex, I did buy a Nikkorrmat EL, but that’s another story.;)

I enjoyed reading this excellent review, and just bought an N-90 in a junk shop. It works well and the sticky back issue was solved in less than 15 minutes and some rubbing alcohol. The VF is very bright and it fits well in my hands, and I like that it takes common batteries. I also have a bunch of EL’s and EL-2;s and an EL-W (the nicest IMO) and in my experience they either work of they don’t, but most of mine work. I also prefer the earlier models because I like the AE with non-Ai lenses. Some of mine have the K screen, some don’t, about 50/50. Iv’e been buying these for about 20 years, I also have a box full of Canon EF’s made about the same time, all inoperative.

Glad you liked the review, Jon. Even though I wrote this review a while ago, my N90s remains a favorite of mine. That’s too bad about the EF. That’s a great camera too!

Out shooting with my EL today. A gem of a camera, in my opinion one of the rare Nikon SLRs that is physically better balanced (and thus easier to use) with the f/1.4 rather than the f/2 50mm prime. And if one is OK with nonAI, the EL is probably the most accessible/affordable and best bang-for-the-buck of any Nikon SLR.

I can understand why you think the Nikon N2000 has maddeningly slow auto focus. Could it be because it’s a manual focus camera? So, yeah, eternity might be a good way to describe it’s AF performance. Who knew?

You’re right, but this review is for the auto focus N2020. I say N2020 at least 30-40 times in the article.

Mike! Me again! My first “real” camera was a 1965 Nikon F in high school, with a Nikkor 50mm lens and a handful of Ritz/Quantaray lenses and a Gossen Pilot 2 meter. Shot TriX and developed at home, printed at school. Shot for the yearbook. Well, that camera is long gone, and in my last 18 months of intensive vintage camera collecting I have avoided Nikon SLRs due to the cost — though I did shell out for an F100 as I had heard good things about it, and it works great. Since some of the lots I have picked up included many lenses, I have good collection of Nikon and 3rd-party Nikon-compatible lenses. I’d love to get a standard-prism Nikon F for the nostalgia, but they are still too pricey for me. But I did pick up a Nikkormat FT2 — nice looking. Well, it had a 3rd-party “kit lens” zoom attached and I could NOT get it off! Pressing the lens release I could not turn the lens far enough clockwise to get it off. The pin coupler on the camera would not move under/past the prism. In fact the widest I could turn the aperture to was F11. The lens had the non-AI ears and they were mated properly to the pin on the camera. I actually had to unscrew the ears and take them off to enable to the lens to rotate enough clockwise to remove it. Even with the lens off the pin coupler won’t move past where it starts to come under the prism/Nikkormat name plate. I don’t think that this is normal — but I have never had a Nikkormat before and I don’t recall this on the F that I had all those 40 years ago. All other functions on the camera seem fine, even the light meter. I have not scrounged around to find a true non-AI/AI Nikkor lens with the rabbit-ear coupler yet — but I was wondering if you, or a reader, had run across this sort of issue with a Nikkormat before? Thanks for your time and the awesome reviews!!!

The FT2 should have the same lens compatibility as any F or F2 with a metered prism. Only when you get to the FT3 and EL2 where you have the Ai indexing tab. I’ve never had a problem with third party lenses, so I cannot imagine why it would get stuck like that other than to think that someone must have messed with it or incorrectly installed it in the first place. Sometimes non-Ai lenses can cause problems with Ai cameras, but assuming it was mounted correctly, it should come off easily.

On another note, I do have a near-mint FT3 that I plan on reviewing next year. I am excited to do a proper review of a mechanical Nikkormat as my only review in this series was in this Three Decades post a couple of years ago.

Can’t wait to see your Nikkormat review!

Well, so the pin which engages the rabbit ears on the lens, to communicate the lens aperture setting to the camera — it was getting stuck on something underneath the Nikkormat label plate. Which was why that ring with the pin would not rotate far enough to allow the lens to be removed. So I took the Nikkormat label plate off and there are some moving pieces of metal under it which engage with the back of the “Pin” plate on that ring — and it looked like they should shift and allow the pin ring to rotate all of the way over towards the lens unmount button — but that was where it was getting stuck. I was able to move these pieces of metal around (they pivot and “cam” against one another, with two stiff-wire “springs”) and then get the pin-ring to move fully in both directions. And the position of these moving pieces of metal did not “fall back” to blocking the pin-ring as before. BUT as I was gently trying to get it all lined up and put the Nikkormat nameplate back on, the lighter of the two spring wires snapped out from wherever it was anchored. And I do not remember exactly where it was anchored. I don’t think that it broke, the ends just popped out — it still is wound and attached to its shaft. Now I need to see how it is supposed to be in order to fix it. SIGH — might have to get the FT2 repair guide that I saw on eBay if I cannot find a source on the web for how it goes together. What I wonder is what these moving pieces of metal are specifically for? They do seem to shift when the pin-ring is rotated past a certain point (where it was getting stopped when I started messing with it) — so they must have something to do with the communication of the aperture setting on the lens to the camera, but they only seem to care about one specific spot (about the 11 o’clock position). I’m going to be upset if I cannot get the camera back to working condition!!!

I agree with your comments on the N90s being the near perfect film camera. My grand daughter still prefers the 8008s, but only because that was the Nikon she got started on and is used to it. She is on her second one now, and I think when it is time for another it will be a N90s. It is really a do everything camera, and with a 50mm f/1.8 AF and one of the very good mid-range AF lenses available (my current favorite is the 28-105 mm AF-D) you can do a lot for not much $$. The only thing you really look out for is cameras that have had leaky batteries – arrrgh, camera death, but also a reminder not to leave batteries in the camera is you are not going to be using it more than a few weeks. The sticky back is pretty simple to fix. Helps to slip the back off so you don’t get any goo in the camera. Too clean off the stick covering I have found that 90% ethanol works well and does not affect the plastic. Your fingernail works fine, or a simple scraper made from a sharpened popsycle stick. I find that I can usually get one completely cleaned up in less than an hour. Remember to use something like a Q tip or tooth pick to get the sticky bits that run over the edge. Once you have finished you can do the final clean-up with one of the automotive products they make for polishing headlight covers (Meguiar’s PlastX is what I use). Looks like new when you put the back on. I thought it might be a little too slick so stuck on a piece of Gorilla Tape. Just didn’t look right so peeled it back off and am just careful. For what they sell for these days I just don’t think you can do any better. Cheers and have fun

Thanks for the post Stephen. Since posting this article, I did what you said and rubbed off the sticky back to reveal the shiny plastic beneath. I did not use the automotive buffing cream though to make it even shiner, but maybe I should! 🙂

Despite writing this review so long ago, the N90s is still one of my favorite SLRs and is still going strong!

“Hello Mike , just got hold of a EL w, everything works as it should, for £16 thats good. so wading through the internet for info lead me to your webpage.

The only downside is I’m peering through strands of fungus/foam seal! on the prism, I can still use it ok , but it becomes annoying as it originates from the shutter scale side.

Looking around the internet I get the feeling people dont want to work on early electronic cameras, and run away from taking on work, and is probably an expensive fix! I dont want to try myself, even though there are hand holding guides out there, I’d sooner have a working example than an unusable body to gaze at!

I enjoy your camerosity podcasts very much, keep up the good work, I.m sure its time consuming putting them all together!

Regards,” Kev