This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which features dead cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot. In the past, these reviews used to come out in a set of three every Halloween or what I called “Halfway to Halloween”, but on occasion I release one at a time. This is one of those occasions.

This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which features dead cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot. In the past, these reviews used to come out in a set of three every Halloween or what I called “Halfway to Halloween”, but on occasion I release one at a time. This is one of those occasions.

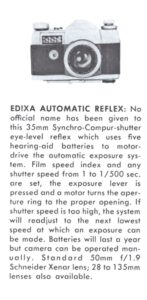

This is the Edixa Electronica, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Wirgin Kamerawerk in Wiesbaden, West Germany between April 1962 and October 1965. The Edixa Electronica was an ambitious camera whose signature feature was programmed automatic exposure, allowing the camera to control both aperture and shutter speeds. Although sharing the Edixa name with other Wirgin SLRs, it shared very little with those cameras, featuring an all new body with fixed pentaprism viewfinder, a Synchro-Compur leaf shutter, and new (to Wirgin) DKL bayonet lens mount. The Edixa Electronica was the darling of Hans Waaske, creator of the Rollei 35 and other cameras, but proved to be too complex and unreliable.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.9 Schneider-Kreuznach Edixa-Xenon coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: DKL Bayonet Mount

Focus: 3 feet / 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism

Shutter: Synchro-Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled Metrawatt Selenium Cell w/ top plate match needle and Aperture Preferred Programmed AE

Battery: (5x) 1.35v Mallory RM-1 Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: PC Sync Port with M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 1062 grams, 848 grams (body only)

Manual: None

History

In 1958, a large number of “electric eye” cameras were introduced to the market all at the same time which for the first time, offered a practical solution to automatic exposure. No longer did a photographer have to understand the relationship between film speed, aperture f/stops and shutter speeds to get proper exposure. With an electric eye camera, you merely put it in Auto mode, wind the film, press the shutter release, and the camera did the rest.

While this was a great achievement in exposure automation, nearly every camera with auto exposure at the time was extremely basic, offering little in the way of manual control, flexible shutter speeds, or interchangeable lenses. These primitive metering systems depended on consistency, and adding too many shutter speeds or other settings simply was not possible. If you were a professional photographer and preferred SLRs with interchangeable lenses but still wanted exposure automation, you were out of luck.

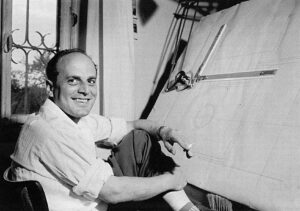

Heinz Waaske, designer of the Wirgin Edixa Reflex SLR sought to change this. If exposure automation could be added to simple box cameras with single speed shutters, certainly it could be done on a more advanced SLR, but how? This question prompted Waaske to look for that answer, which led him down the path towards working on a top secret new camera. The workshop where the earliest work was completed for Waaske’s new camera was done in total secrecy, not even the president of Wirgin, Henry Wirgin knew what Waaske was doing.

In August 1958, Waaske would file a patent for a new type of automatic exposure control and then started work on building a camera around it. Having been responsible for Wirgin’s current Edixa SLR lineup, he retained the same name, however the camera would be very different from anything Wirgin had released to that point.

Most automatic exposure systems of the time operate on the same principle in which a photodiode made of selenium converts light into a small electric current which moves a small needle. When the automatic exposure system is activated, the position of the needle is “trapped” keeping it in a fixed position which is then transferred to the lens diaphragm, automatically increasing or decreasing the amount of light which can pass through the lens to the film plane.

Waaske’s system was similar, except instead of a moving needle and a trap system activated by the press of a button, his system used a series of tiny electronic motors which could detect the amount of electricity generated by the selenium meter and automatically set both aperture and shutter speed based on a predetermined exposure table. This in effect works like a primitive version of what we call Programmed AE mode, except unlike current systems in which a wide combination of both shutter and aperture speeds can be detected, Waaske’s system primarily controlled aperture first, and would only adjust the shutter speed when the needed light exceeded the limits of the diaphragm. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the system, is that without power, the camera still operates entirely in manual mode. With most early AE systems, automatic cameras had limited or no manual exposure capabilities.

Full Disclosure: I’ll admit, I really struggled to fully understand how the auto exposure system in the Edixa Electronica works. I could not find a user manual for the camera, nor any published reviews of working cameras. Without a working camera myself, I was never able to observe one in action, so I am taking some liberties in how I think the system worked.

Although complicated, Heinz Waaske’s system worked, and around it, he built an all new camera in a more sleek and compact body with a Synchro-Compur leaf shutter and the Deckel “DKL” bayonet lens mount. Lenses made by Schneider and Steinheil were available in focal lengths from 28mm to 135mm giving a level of flexibility never before seen in “electric eye” cameras of the time. The choice of a leaf shutter instead of the focal plane shutter used on all other Wirgin Edixa SLRs was made out of necessity as early prototypes using a focal plane shutter were too complex and would not fit into a reasonably sized camera. A leaf shutter was used because it was more compact and allowed for more room for the various electronic motors required to make everything work together.

Heinz Waaske’s new camera was revealed in March 1960 in a Wirgin company newsletter, and ten samples were introduced to the public in September of that year at Photokina as the Edixa-Motorkamera, the world’s first fully automatic SLR camera with interchangeable lenses. A second SLR released that year, the Royer Savoyflex Automatic featured shutter priority auto exposure, but lacked interchangeable lenses.

The Motorkamera was a triumph of design and simplicity. Never before was there an SLR camera with the ability to control both aperture and shutter speeds at the same time. Combined with high quality lenses from respected German lens makers, the already well regarded Synchro-Compur shutter, and a Metrawatt selenium meter, the camera had other innovative features such as the ability to automatically index the lens being attached. Even the mighty Nikon F required a complicated external linkage to index the maximum aperture of a lens before the exposure meter could accurately detect the lens. Another thoughtful feature was that the lining of the bottom mounted battery compartment was made out of a special acid-resistant plastic which would protect the insides of the camera in the event a battery leaked.

If you are reading this article and are thinking that upon revealing a revolutionary new SLR with the convenience of auto exposure while still being a fully functioning SLR with manual control and interchangeable lenses, the company who made it would be eager to get it into consumer’s hands, you’d be wrong. As it turned out, upon seeing the Edixa-Motorkamera and all the things it was capable of, representatives at Wirgin believed that the new camera would immediately render the rest of the company’s offerings as out of date, and make them difficult to sell. In addition, as a result of the new camera’s complex and delicate inner workings, new factory workers would need to be trained to handle the difficult assembly of the camera, something that would further drive up the cost of the camera. Fearing that releasing the new camera would hurt the company’s profits, the release of the Motorkamera was put on hold.

It would take nearly two years for Henry and Max Wirgin and the rest of the company to change their tune and become ready to introduce the new camera. Initially, the name Edixa Motoric was chosen for the camera, but at the last minute, this was changed to Edixa Electronica as electronics were considered the technology of the day and having the word “electronic” attached to a new product would make it buzz worthy. At least one example, owned by Heinz Waaske himself was produced bearing the “Motoric” name. The Wirgin Edixa Electronica would go on sale in April 1962.

Unfortunately, in the time between the camera’s debut at Photokina in 1960, and its release in the spring of 1962, a large number of auto exposure cameras had hit the market from the AGFA Optima to the Kodak Retina Automatic. Although none of these cameras offered programmed AE and none were SLRs, it would appear that the combination of AE in an SLR was not one that people wanted. The price of the camera was an also issue, initially selling for 750 DM with the Schneider Xenar 50mm f/2.8 lens and 651 DM with the Steinheil Culminar 50mm f/2.8 lens, the Edixa Electronica was far beyond the price range of someone looking for a fully automatic camera. The pros who might have had the budget for a 750 DM camera preferred cameras that didn’t think for them.

Strangely, the Edixa Electronica sold better in America than it did in Europe. Max Wirgin who was in charge of US distribution noted that Americans were more accepting of the new technology and found the action of moving needles and the hum of the electronic motors to be exciting. Owners of these cameras would often demonstrate their operation, not by making exposures, but by continually pointing the camera at bright and dark light sources and showing their friends how the camera automatically adjusted.

Even with a boost from the Americans, sales of the Edixa Electronica were poor. Combined with a high cost, the introduction of much less expensive and increasingly advanced Japanese SLRs was the nail in the coffin for the high tech/high price Edixa Electronica. Between the camera’s release in April 1962 and October 1964, only 1100 cameras were sold. Another 3000 would be produced by the company before being discontinued in October 1965, bringing total production to about 4100 units (including unsold new stock). This is in comparison to the traditional focal plane Edixa cameras which at that time averaged 26,000 sales per year.

The fallout from the Edixa Electronica also had an impact on Heinz Waaske’s career at Wirgin. Although responsible for the company’s successful Edixa SLR line, Waaske’s relationship with Henry Wirgin was strained. A big part of this was that Waaske had demanded to be compensated for his work on his 1958 patent. Although the camera it was used in was not a sales success, Waaske thought that the technology still had value, but after receiving a lowball offer from Henry Wirgin for 1000 DM, his time at the company had come to an end. Waaske would produce one more camera for Wirgin, a subminiature 16mm camera called the Edixa 16, but the damage was done, and in 1964 Heinz Waaske would leave the company. This proved to be a wise move however, as Waaske would eventually turn up working for Rollei and while there would go on to produce the extremely popular Rollei 35 series, among other cameras for the struggling Rollei Werke.

Today, Wirgin SLRs are generally well regarded cameras by collectors. A combination of being a huge number of them out there, plus generally good performance and excellent cosmetics make them a popular option for collectors and shooters alike. Although very much a part of the Edixa family, the Edixa Electronica usually flies under the radar, most likely due to its rarity and lack of awareness of the model. With just over 4000 units ever made, these cameras do not show up for sale often, and because of the complex inner workings, are even less likely to be found in working order. Still, these are fascinating cameras that tell an important, albeit small part of the story of the German camera industry.

My Thoughts

Germany produced a great deal of wonderful cameras of many types. Rangefinders, SLRs, TLRs, subminiatures and everything in between. While there are a great deal of German cameras that I’ve become fond of over the years, one that consistently makes me smile each time I pick one up, is the Wirgin Edixa Reflex. My collection has slowly grown to contain a variety of these wonderful SLRs, a large reason being I find them to be some of the most beautiful cameras ever made. Featuring a design that sticks more closely to the shape and control layout of traditional SLRs, but also featuring all metal bodies and lenses with soft curves and creases in just the right locations. Along with the Japanese Miranda SLR, I believe that a clean 1950s Wirgin Edixa is one of the best looking cameras ever made.

When I had heard that Wirgin once made a AE capable Edixa with a Compur leaf shutter in an entirely new body design called the Edixa Electronica, I was intrigued. These cameras were rare and hard to find, but after years of looking for one, I was finally able to acquire one from the collection of Kurt Ingham. This Wirgin Edixa Electronic was in cosmetically excellent condition with a gorgeous Schneider-Kreuznach Edixa-Xenon 50mm f/1.9 lens, but sadly the shutter was inoperable.

Still, the camera was gorgeous and the first time I held it, I quickly fell in love with the look and feel of the camera. Having a Deckel shutter, the Edixa Electronica shares quite a bit in common with other DKL mount SLRs like the Kodak Retina Reflex and the Voigtländer Bessamatic and Ultramatic such as the back plate exposure control and similar looking Schneider lenses. Even with those similarities, the Edixa has its own design, with gentle curves, beautiful chrome, and creases that are both softly curved and sharp at the same time.

The build quality feels very good, at least as good as the company’s focal plane Wirgin Edixa SLRs, and comparable with other DKL mount SLRs. Weighing in at a portly 1062 grams with the 50mm f/1.9 Schneider lens, the Edixa Electronica is not a light camera and would require a nice and thick neck strap to dangle from on long photo shooting sessions.

Up top, the control layout is rather sparse. On the left is the combined film rewind knob and an ASA film speed dial beneath. Film speeds are shown in ASA and DIN and range from 12-1600 in green and 12-33 in black respectively. Unlike other Wirgin Edixa SLRs, the viewfinder is not interchangeable, but that has a subtle benefit of being a bit lower profile than that of other Wirgin SLRs.

To the right of the prism is a curved meter display which I struggled to understand how it worked as I neither had the camera’s user manual, nor was this camera working properly. What little I do understand is that the meter and the motorized auto exposure system is activated by pressing forward on the stubby black lever to the side of the film advance lever. This effectively puts the camera into AE mode, but without it, the camera still works in full manual mode.

To the right is the combined film advance lever and exposure counter. The film advance lever has a fairly long 270 degree throw and must be completely wound before it will return to its original position. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made on the current roll of film and does not automatically reset, requiring you to manually turn it back to 0 after loading in a new roll of film.

Below the exposure counter and film advance lever is a small black triangle shaped lever which controls the metering system of the camera. With this camera being inoperable, I was not able to test this, so I can’t say for sure how it works, but I noticed that when pressing and holding this black lever into a forward position, two white arrows appear in the curved meter readout on the top plate of the camera. My best guess is that a needle coupled to the selenium meter should appear at this time to show whether or not proper exposure can be made in between the two white arrows. When the needle is in between the arrows, proper exposure can be made, but if it is outside the arrows, perhaps the shutter becomes locked and will not fire. Unless I find a working copy of this camera or at the very least, a user’s manual, I can only guess at how this works, but I do know for sure that the camera should still work fine in full manual mode when not using the metering system.

Around back, a deeply recessed eyepiece is surrounded by a black frame and provides a large opening into the fixed pentaprism. To the left is the exposure control wheel which functions the same as similarly designed wheels on other DKL mount SLRs. On these cameras, the lens aperture is controlled by turning this wheel coupled to the shutter speed control around the lens mount. It works the same as it does on cameras like the Kodak Retina Reflex and Voigtländer Bessamatic, but if you have no experience with cameras like this, can be a bit awkward and remains one of my least favorite things about using DKL mount cameras. In the center of the film door is a round film reminder dial.

The bottom of the camera is dominated by the very large battery compartment which swings open to house five Mallory RM-1 Mercury batteries. Unlike many mercury batteries in which there are modern alkaline equivalents, there are no mass produced options available, only boutique style batteries like the Exell A1PX which sells at Amazon for $9 each.

The Edixa Electronica requires power for the motorized auto exposure system. Without power, the camera will still work in full manual mode. Opening the battery door is a two step process, the first of which is swinging out a hinged arm which doubles as a foot to stabilize the camera while sitting on a flat surface, and then sliding a latch underneath to the side before the door will open. To the side of the battery compartment is a raised rewind release button and on the other site a large foot with a 3/8″ tripod socket in the center. While 3/8″ tripod sockets were common in the mid to early 20th century, it is uncommon to still see them on cameras sold in the 1960s.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical with the only difference being the film door release on the right side. Opening the door requires pressing in on two spring loaded tabs which are at the top and bottom of the latch. This design is opposite of most side door latches in which you pull out on a tab to release the door. I actually prefer the method used on this camera as I believe you’d be less likely to unlock and open the door with film in the camera by accidentally squeezing in two tabs at the same time. The Wirgin Edixa Electronica lacks strap lugs which is unfortunate, especially considering how heavy this camera is. To have to rely on the thin leather strap of the original ever ready case seems like a recipe for disaster. Not shown in pictures here, but from the left side of the camera, you can see the left side of the lens mount which has a green slider for choosing M and X flash sync, or “V” for a self-timer. Like all leaf shutter cameras, it is advised not to try the self-timer unless you are certain the camera has been serviced, as the clockwork mechanisms behind these timers can easy jam up the shutter if not lubricated correctly.

The left hinged film door swings open to reveal the film compartment. Film transports from left to right onto a nonremovable metal take up spool. The spool has a single slot for holding the leader when inserting a new roll of film. The camera’s serial number is engraved into a plate directly below the opening for the film gate. Like all leaf shutter SLRs, a capping plate is visible while the camera is not in use, to protect the film from light as the shutter opens and closes during composition. The film door has a large metal pressure plate with horizontal ribs across it, which I suppose are there to reduce friction as film passes over it. Overall, the film compartment is nicely appointed without any of the rough edges you often see on less expensive cameras. A felt strip near the door hinge protects the compartment from light leaks.

Looking down upon the top of the shutter, you see rings for aperture and shutter speed. This design is consistent among all cameras with the DKL mount, but like those other cameras, you cannot control aperture directly. Shutter speeds and f/stops are always coupled on these cameras, and can only be modified using the exposure control wheel on the back of the camera. Changes to the shutter speed always make a corresponding change to the aperture ring, which for me, is very frustrating and leads to a slower experience. While I have gotten used to this on the many DKL mount cameras I’ve used, I can wholeheartedly say that if I was a photographer in the 1960s when these cameras were new, this feature alone would be cause enough to not buy one. I would much rather prefer more standard controls found on other focal plane shutter SLRs of the same era. In front of the aperture ring is the focus ring with a focus range scale. The scale has measurements from 3 feet to infinity in red and 0.9m to infinity in black. This being the 50mm lens, the minimum focus is reasonable, but users of telephoto lenses on all DKL mount SLRs will find very unreasonable minimum focus distances. Like all Schneider lenses on DKL mount cameras, an interactive depth of field scale features two red arrows that move with the chosen aperture, to show how much depth you have at any given focus distance.

Up front, a rectangular selenium exposure meter adorns the area in front of the shutter release, above and to the left of the lens mount. To the left of the lens is the front facing cable threaded shutter release. I have always liked front facing shutter releases, especially on large and heavy cameras like this as I feel it helps better stabilize the camera while it is pressed against your face. While I have never done any sort of scientific measurement, I suspect that you can gain an extra stop of handheld stability while using a camera with a front shutter release. Around the shutter release is a knurled ring labeled A and Z, which at first I thought had to do with the direction of film transport, but it is just a shutter button lock. With the dial turned to Z, the shutter release button cannot be pressed.

DKL mount SLRs always have the bayonet release at the very bottom of the lens mount. A curved metal tab must be pressed up into the mount to unlock the lens and allow it to be removed. With the button pressed, rotate the lens counterclockwise to remove, and clockwise to reinstall. Red index marks on the lens flange and at the 12 o’clock position of the lens mount must be aligned while reinstalling the lens.

Also like other DKL mount SLRs, although the mount is technically the same, small physical changes to the shape, size, and orientation of the bayonets make interchanging lenses between different brands of SLRs impossible. With the Wirgin Edixa Electronica, I also had various Kodak Retina Reflexes, a Voigtländer Ultramatic and Bessamatic, Braun Paxette Reflex, and a Zenit 6, and the Schneider Edixa-Xenon 50mm f/1.9 lens could not be mounted to any of them, or vice versa. I did not test any of the DKL rangefinder as even if there was some way to mount those, they wouldn’t focus correctly.

I mentioned earlier my lack of fondness for the exposure control wheel common on all DKL mount SLRs, but by far, this forced incompatibility between brands using the same lens mount is the absolute worst thing about owning a DKL mount lens. Imagine if every company who made LTM rangefinders or M42 SLRs did something to make their lenses incompatible with other brands using the same mount. That these companies all chose the same mount and went out of their way to make changing lenses between brands difficult is one of the reasons for the mount’s failure and something that still confounds collectors today.

This being a camera of the dead article, the shutter on the Wirgin Edixa Electronica wasn’t working, which also meant that I could not see through the viewfinder as the shutter has to open to allow light to pass through to the reflex mirror and then up into the prism. I was not able to get a view of what the viewfinder looks like, but comparing this camera to other early 1960s SLRs of the era, more than likely the image will be darker than what you might expect from a 1970s or 80s camera. Looking through the viewfinders of the 4 other DKL mount SLRs I have, they all have a split image focus aide, with the Kodak and Voigtländer also having a microprism collar around it, so the one here almost certainly has some kind of focus aide in the center of the ground glass. There is a good chance that a Fresnel pattern will be visible over the rest of the focus screen to improve edge and corner brightness, and there almost certainly will not be any kind of exposure read out visible. Overall, I’d expect the viewfinder to be neither better nor worse than other, comparable cameras.

The Wirgin Edixa Electronica is an interesting camera, made by a company who at the time had the potential to break out of the established norms of 35mm German SLRs. In an industry still dominated by rangefinder cameras, there weren’t too many innovative SLRs at the time, and the inclusion of programmed auto exposure from a German manufacturer was a big deal. Unfortunately, the Edixa Electronica failed due to a familiar combination of a high cost, the availability of simpler and less expensive Japanese imports, and also internal mismanagement. Heinz Waaske’s design was pioneering and innovative, but his work failed to gain support within his company and ultimately led to his departure in 1964. As a result, the Edixa Electronica remains a one off by a forgotten company who quickly would fall out of prominence in the 35mm SLR market.

I am happy to have come across this particular camera and enjoy looking at it and playing with its various controls. That I was unable to use it wasn’t as big of a bummer as it might seem as its combination of features is similar to enough to other leaf shutter SLRs of the same era that I think I can fairly accurately predict what the shooting experience would have been like. I probably would have complained about the cumbersome exposure metering system, including the programmed AE mode which likely wouldn’t have been accurate due to the age of the selenium meter. I probably would have said that the viewfinder was good enough for brightly lit outdoor scenes, but wasn’t ideal indoors, and that the excellent optics of the Schneider lens produced excellent looking images.

If I ever find another example of this camera that works, or if I am ever able to find someone who can get this one working, I’ll be sure to come back here and update this review, but for now, the Wirgin Edixa Electronica becomes the latest Camera of the Dead!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Edixa_Electronica

https://knippsen.blogspot.com/2020/03/wirgin-edixa-electronica.html

https://www.fotohistoricum.dk/riess_wp/de-andre/hos-wirgin-d/at-wirgin-gb/