This is a Contax I, a 35mm rangefinder camera produced by Zeiss-Ikon in Dresden, Germany between the years 1932 and 1936. This particular version is considered by collectors to be a Version 7 or Type F model, offering several upgraded features from the original model, such as additional slow speeds, a tripod support, new arrangement of rangefinder windows, and a redesigned infinity lock button. The Contax was developed to go head to head with Ernst Leitz’s Leica camera and offered a variety of improvements over the much simpler Leica II and III which were the current models at the time. Most photographers at the time considered Zeiss lenses to be superior to those used by Leitz and together with a more advanced camera, the Contax was the most advanced and highest quality 35mm camera in the world during the years it was made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/2.8 Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Contax Double Bayonet

Focus: 0.9 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Separate Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder and Optical Viewfinder

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Metal Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Built-In Mask for 8.5cm Lenses

Weight: 704 grams, 579 grams (body only)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ConnoisseurandtheContax.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax rangefinder was at the time of it’s release, the most fully featured and innovative 35mm camera ever built. It was designed to compete with the Leica rangefinder, and although from a sales point, it was not on the same level, it held it’s own in terms of features, image quality, and when working, durability. Early Contax cameras are very hard to find today, and even harder in working condition, but in the rare instance where one can be had in good working condition and some of the best cameras ever made. Pay no attention to those telling you these were inferior to their Wetzlar counterparts, or that they’re not easy to use, as I think they are far more interesting and fun to use, and anyone who tells you a prewar Leitz lens is optically better than a Zeiss lens, has clearly never handled one. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 16.8 | ||||||

History

Ford vs Chevy, Windows vs Mac, Coke vs Pepsi, long have there been debates about which of these products was better. For photographers in the early/mid 20th century, an often heated debate was that of Leica vs Contax rangefinders. Both cameras were produced by two of the most respected German optics firms of the 20th century and each represented a huge leap forward in quality and features in the 35mm rangefinder segment. But despite what was a long list of similar features on each camera’s spec sheet, how each model looked and worked, they couldn’t be more different.

The Contax’s lens mounts, shutter, rangefinder, and entire body design was totally different from that of the Leica. About the only thing that the two cameras shared in common was that they both used double perforated 35mm film, and even then, there were differences. Most of the design of what would become Zeiss-Ikon’s first Contax rangefinder is owed to a Zeiss design engineer named Dr. Heinz Küppenbender.

Küppenbender was born in 1901 in a small town in western Germany called Wadniel and later studied at the Technical University of Aachen, graduating with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1924. In 1927 he joined Carl Zeiss Jena as an engineer where he would continue his studies, eventually earning his doctorate in 1929 from the Technical University of Stuttgart.

After the 1926 merger that formed Zeiss-Ikon, a former Ica employee named Dr. Emmanuel Goldberg was chosen to run the new company.

Tasked with combining the products, factories, and staff of the four companies that were included in the merger, in September 1927 Goldberg recruited Küppenbender from Jena to help organize and update the company’s product offerings.

At the time, Zeiss-Ikon’s compact camera offerings were products like the Kolibri, a compact 127 “Vest Pocket” camera and the Ermanox, a small plate camera with what was at the time the world’s fastest f/1.8 Ernostar lens, but there was nothing to compete with the Leica.

Küppenbender studied the inner workings of the Leitz Leica camera. First released in 1925 and based on a prototype from 1913 by former Carl Zeiss employee Oskar Barnack, the Leica was quickly becoming one of the most popular cameras in Germany. With total sales by 1930 of more than 60,000 units, Zeiss-Ikon knew they needed to compete, so Küppenbender convinced Goldberg that an influx of new talent was needed to develop an all new 35mm rangefinder camera.

In 1929, a former Ernemann employee and brilliant lens designer named Ludwig Bertele was tasked to work on lenses for an upcoming 35mm rangefinder camera before the camera even existed. With Bertele’s expertise designing lenses, and Küppenbender and his team working on a new camera, things were starting to finally move in the direction of Zeiss-Ikon having something to compete with the Leica.

While analyzing the inner workings of the Leica, Küppenbender found it to have many shortcomings to it’s design. Starting with the shutter, which on the Leica traveled horizontally across the 36mm film plane, was made of cloth and had a top speed of 1/500, Küppenbender found it to be erratic in it’s timings. While traveling horizontally across the longer distance of the frame, the speeds of the curtains had to accelerate at the start of exposure, and rapidly decelerate near the end in order to maintain even exposure, but Küppenbender found there to be a wide range of variances among the different samples he analyzed. Another problem was that due to the cloth material, when the lens was focused to infinity, it effectively acted as a magnifying glass on the shutter material, and if pointed at the sun or any bright light source, could easily burn a hole in the material which would require replacement of the curtains.

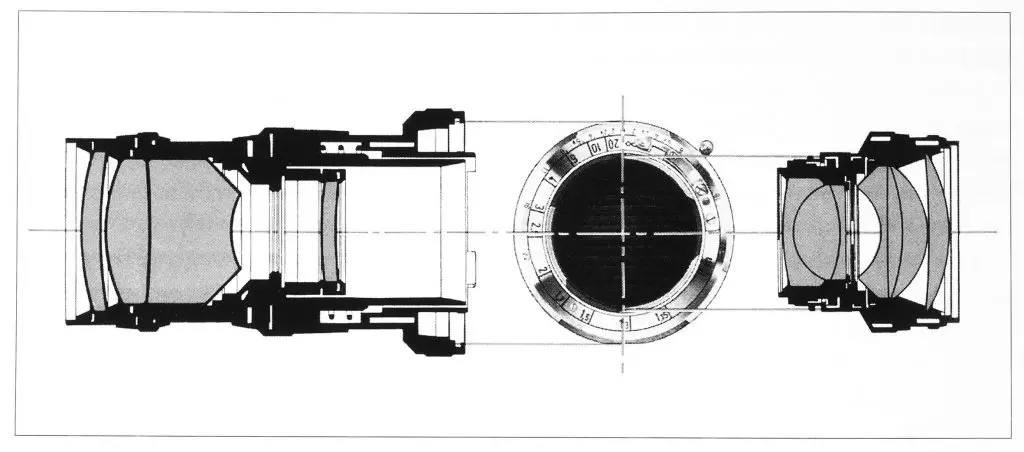

To overcome these obstacles, Küppenbender designed a vertically traveling metal shutter that not only solved the problem of burning holes in the curtains, but by rotating the shutter 90 degrees from that of the Leica, the shutter only had to travel a shorter 24mm distance, meaning that more precise timings and a top 1/1000 shutter speed would be possible.

Unlike vertically traveling metal shutters like the Copal Square that would become common in the later part of the 20th century, the Contax shutter used a series of horizontal metal slats that are held together by silk ribbons. Each curtain would roll up like a garage door both above and below the film gate. To better illustrate the action of the shutter firing, I made a slow motion video of a Contax shutter firing at 1/25 and 1/1000. Watch the video below and you can see how it works.

Another area that received significant attention was the rangefinder. The Leica used two separate windows, one for the coupled rangefinder, and the other for the main viewfinder. The two windows were about an inch apart, slowing the photographer down when he or she had to move their eye between the two windows. For his new camera, Küppenbender wanted the two windows to be as close together as possible.

Yet another perceived shortcoming of Leitz’s design was that Leica rangefinders used mirrors separated by air that were cemented to arms which were coupled to the lens via an arm with a wheel on the end. While creating a new rangefinder, Küppenbender found that cementing small mirrors to a metal plate like the Leica used was more difficult than he had imagined. For one, getting a cement that could handle small bumps to the camera without having the mirrors break off, while also being able to be applied thin enough so as not to cause a measurement error from the hardened cement between the back of the mirror and it’s plate was a challenge. To overcome this obstacle, rather than use mirrors, Küppenbender created a rotating wedge prism that used a solid piece of glass that rotated on a central axis directly connected to the focusing helix. This had the combined benefits of a perfectly reflected rangefinder image, it would never fall off if the camera was dropped, and it eliminated any error caused by the cement holding the mirror in position.

As with the Leica Model C, Zeiss-Ikon wanted their new camera to have an interchangeable lens mount, but they found that the screw mount was not only slower to put on and take off, but that the screw threads could be damaged by mounting the lens incorrectly, and the exposed focusing arm could be damaged if mishandled. As a result, an all new bayonet lens mount was created that not only was faster to take on and off, but kept all the focusing parts within the lens mount itself, at least for 50mm lenses. While superior in speed and reliability, the internal Contax mount would only work for lenses of a single focal length. In order to mount anything other than a 50mm lens, the pitch of the internal helix would be incorrect, which required a second, external bayonet to be used with lenses that had their own helix which not only added complexity to the lenses, but increased their cost.

The final area of attention that Küppenbender considered was the manner in which film was loaded. When Oskar Barnack created the first Leica, he prioritized body rigidity and the ability to keep unwanted light out of the film compartment, so he went with a bottom loading design in which both the take up and supply spools came out of the camera, the film was loaded and then slid in through the bottom of the camera. Although effective at keeping light leaks out, this method was slow and clunky, requiring 5 full pages explaining how to load film into the Leica Model A’s user manual. Another shortcoming of the bottom loading design was that since the photographer would never have access to the film compartment, it was difficult to inspect the shutter or clean broken pieces of film that often fell off as film transported through the camera.

To solve all of these problems, Küppenbender created a back loading design in which the entire back and bottom of the camera came off at once, revealing the entire film compartment. This not only sped up loading of film into the camera, but solved the issue of being able to clean broken chips of film out of the film compartment.

Of course, at the time when both the Leica and new Zeiss-Ikon camera were being built, there was no universal standard for daylight loading 35mm film cassettes. For both cameras, photographers would need to either bulk load their own 35mm cinema film, or acquire special cassettes developed for each camera.

Leitz’s system was simpler, still requiring a special supply cassette, but winding onto a take up spool in the camera, which would then be rewound back into the supply cassette at the end of each roll. Zeiss-Ikon created special cassettes that would use a cassette to cassette transport that didn’t require any rewinding at the end of the roll. While a cassette to cassette transport has some advantages, Leitz’s system proved to be more popular and in 1934 when the Eastman Kodak Company would create their new type 135 format cassette, they based it off Leitz’s method.

The last challenge for Zeiss-Ikon’s new camera was what to call it. For that, they created a contest among their own employees to come up with a name. The name “Contax” was decided upon and for his or her winning suggestion, an unnamed employee received a prize of 5 Marks.

Fun Fact: Did you know that when Zeiss-Ikon released the first Contax camera in 1932, it wasn’t the first time they had used the name “Contax”? The first use of the name was by Contessa-Nettel, one of the companies who would later merge to form Zeiss-Ikon in 1926. The following information originally appeared in the Spring 1994 issue of Zeiss Historica.

In 1924, while working at Contessa-Nettel, Dr. August Nagel, in addition to building cameras, also created products for the German automobile industry. One of these products was an automobile directional signal called the “Contax”. Nagel’s Contax was a simple device, consisting of a round black metal housing containing a rotating red arrow. Under normal operation, the arrow pointed up, indicating the vehicle was traveling forward. To signal a turn, the driver used a switch with three contacts that would rotate the arrow left or right to let other motorists know the vehicle was turning.

A number of German automobiles came equipped with the Contax, including Daimler-Benz, Krupp, Opel, and others. In 1926, when Contessa-Nettel was merged to form Zeiss-Ikon, all of it’s trademarks became part of Zeiss-Ikon, and production of the Contax continued for a few more years, when it was eventually replaced by traditional electric turn signals. Versions of the Contax exist with and without Zeiss-Ikon markings.

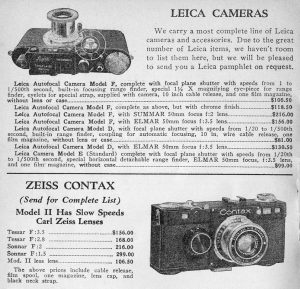

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax camera would made it’s debut in 1932 with a lot of ground to make up if they wanted to match the Leica’s soaring popularity. The Contax was an extremely complicated camera with specs and technologies in it that the world had never seen before. While impressive on paper, the Contax was also very expensive. In their 1935 catalog, Central Camera in Chicago sold the Leica Model D (today called the Leica II) with f/3.5 Elmar lens for a not insignificant $130.50.

Prices for the Contax were quite a bit higher, ranging from $156 when equipped with a collapsible 5cm f/3.5 Tessar all the way to $299 with a 5cm f/1.5 Sonnar. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to around $3450 and $6600 today, making a Contax rangefinder quite a significant investment.

Zeiss Contax Model II: In Central Camera’s 1935 catalog showing the Zeiss-Ikon Contax for sale, it refers to the camera as the Model II, now with slow speeds. This is the only occurrence I’ve seen of the camera referred to as the Model II as the real Contax II would not be released until a year later. Whether this was a short lived namesake for the slow speed equipped models, or if it was just a stretch by employees at Central Camera is unclear.

The complexity of the Contax allowed Zeiss-Ikon to proclaim it as the world’s most advanced 35mm camera, it also led to some significant growing pains. Early models were plagued with reliability issues that often required the cameras to be sent back to the factory to be serviced.

Often, when a camera went back to Zeiss to be repaired, it would be stamped with a second letter next to the serial number to indicate the year in which the repair was done. Early Contax rangefinders almost always have two date codes.

Although all Contax rangefinders produced from 1932 until the Contax II’s release in 1936 were officially considered to be the same model, many changes were made to the camera over those five years. Some of the changes added new features such as a wider selection of slow speeds not available in the original model, and others improved on parts of the design of the camera in the interest of reliability and user satisfaction.

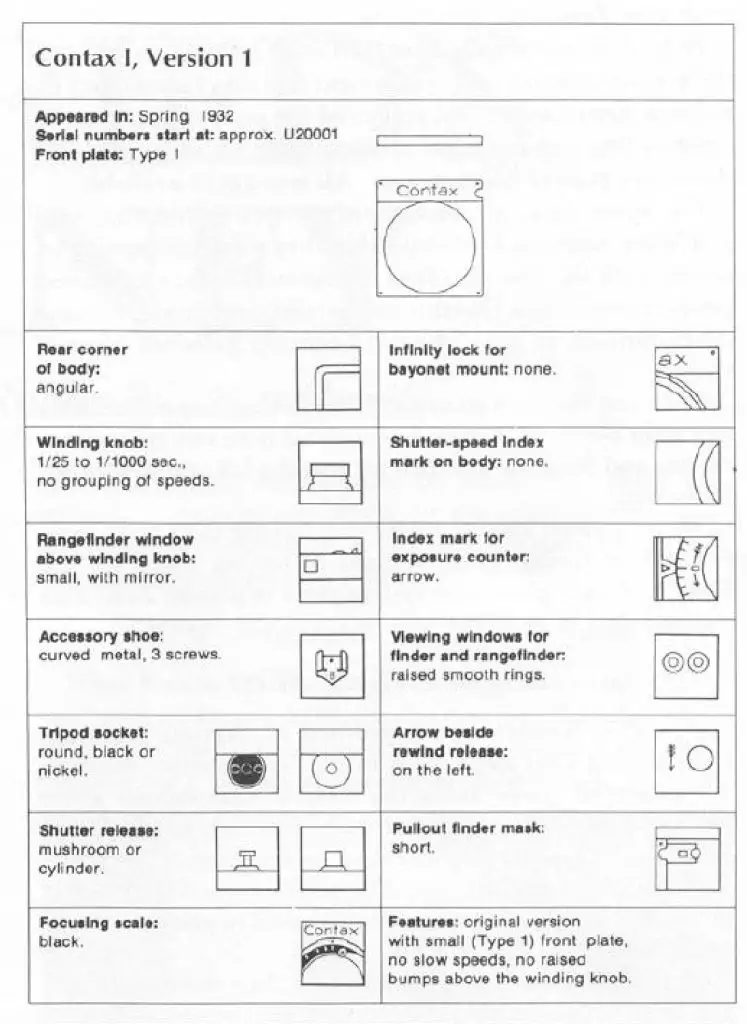

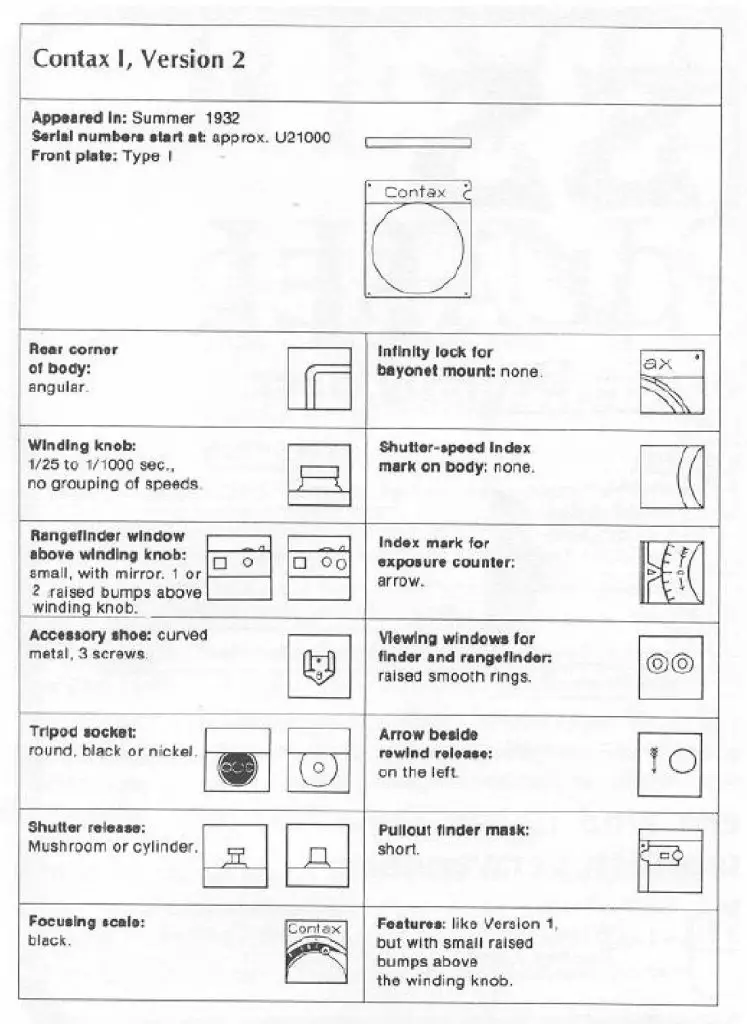

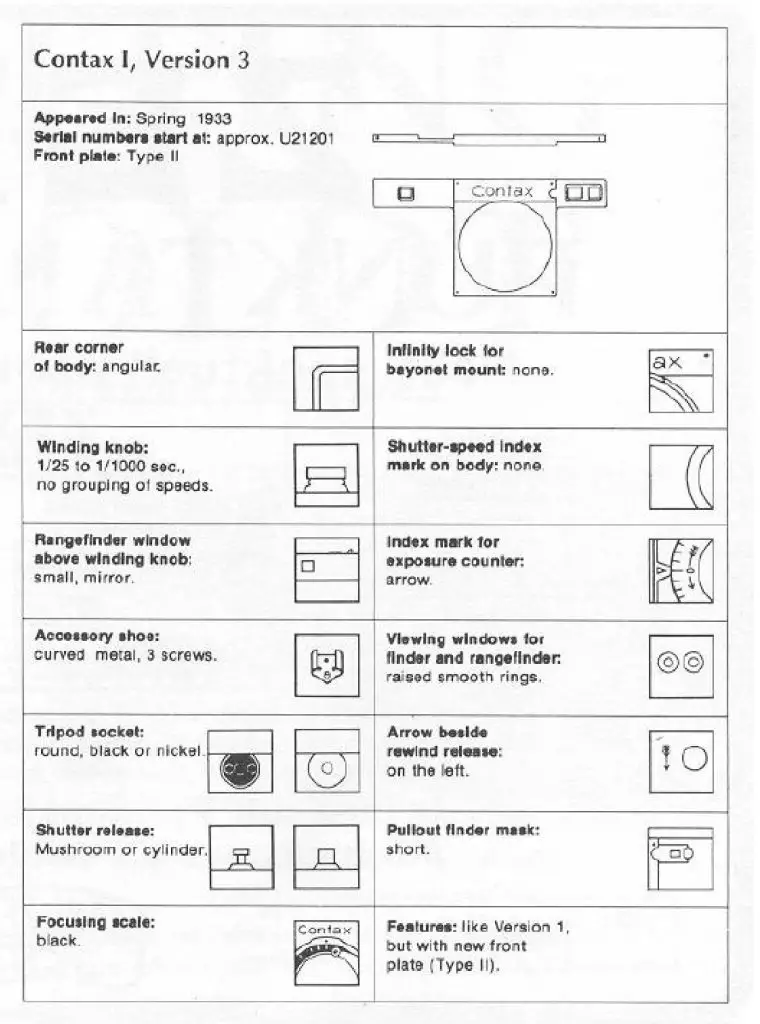

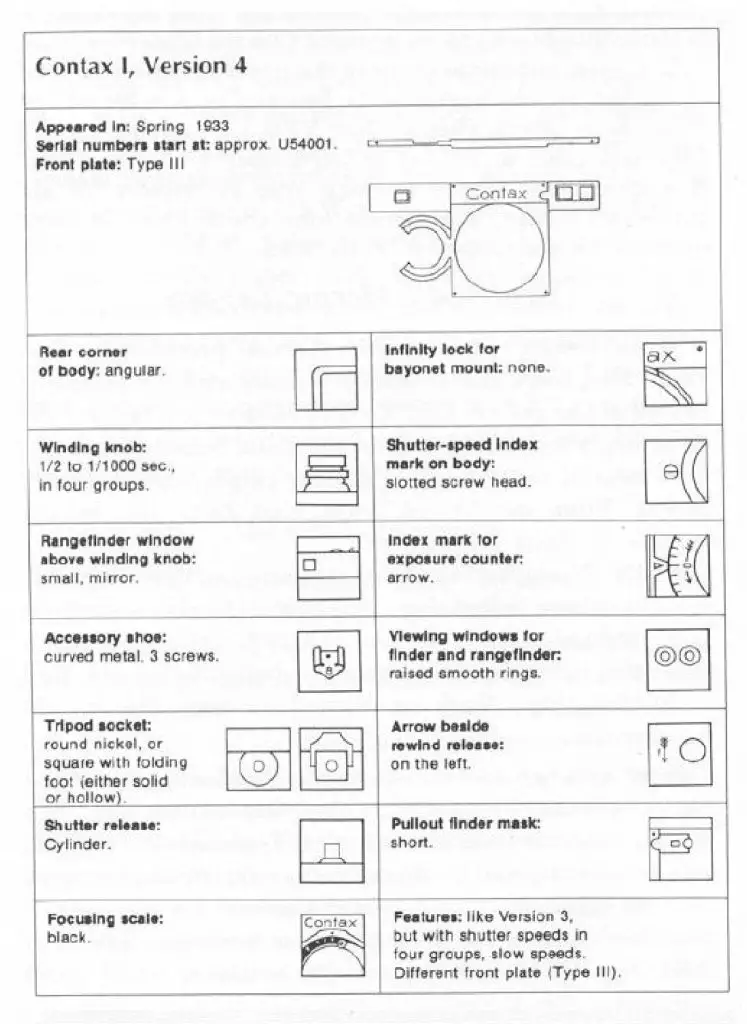

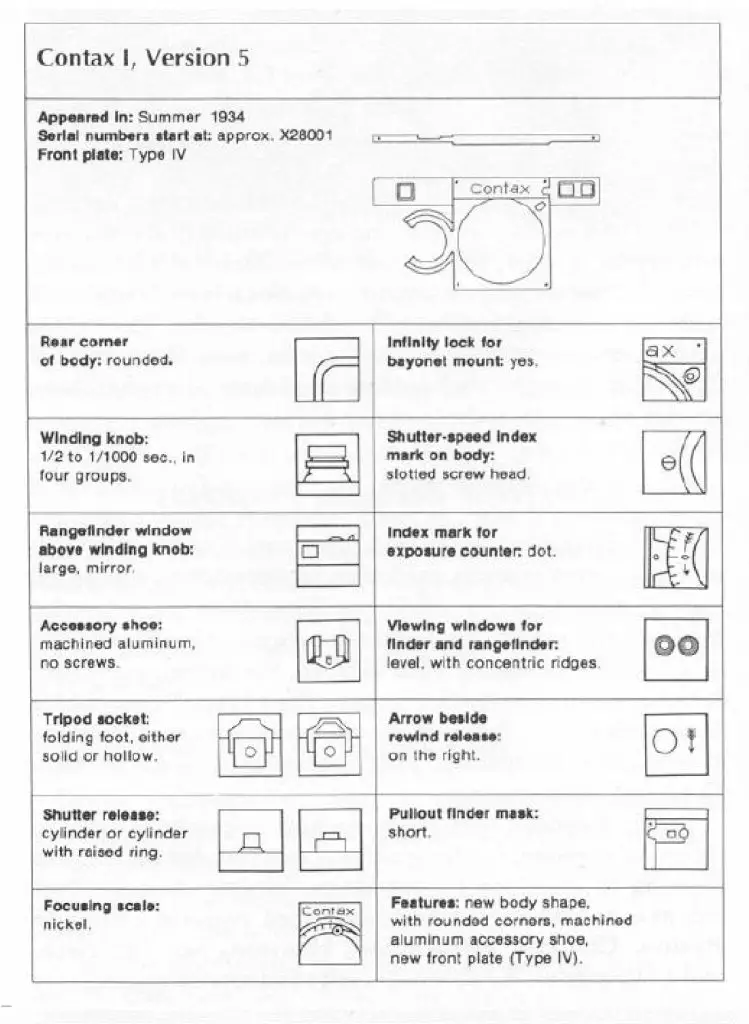

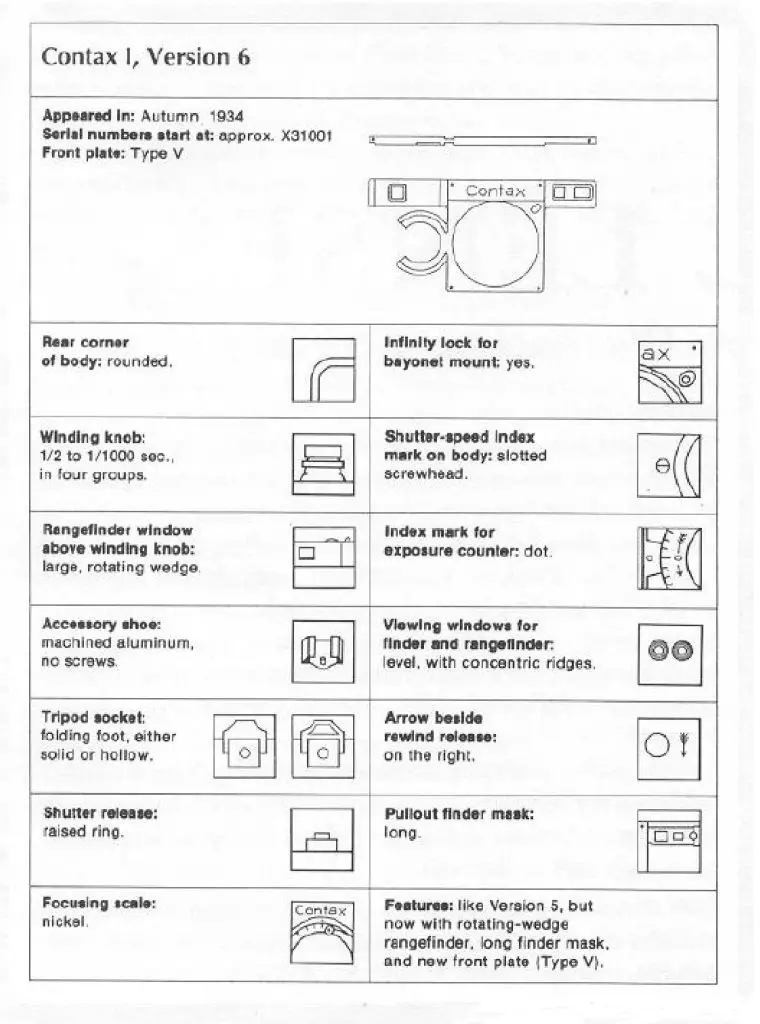

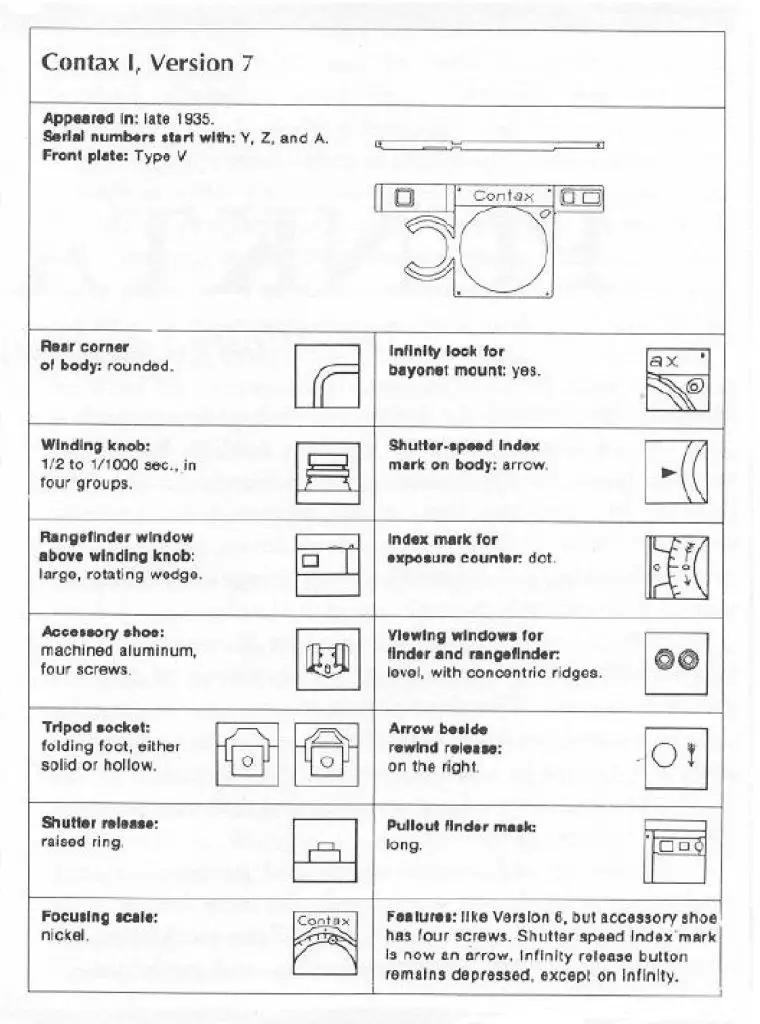

Over the years, many collectors have come up with a categorization of the major changes seen in Contax I rangefinders. The most common one found today is the one found in Jim McKeown’s camera books, listing six distinct versions of the Contax, labeled models A through F. However, an earlier version published in 1985 by the Zeiss Historica Society written by Dr. Siegfried Schlegel classifies seven versions, numbered 1 through 7. A conflicting classification created by Hans-Juergen Kuc closely matches McKeowns with only six.

It is likely that McKeown based his six model system on Kuc’s system, simply eliminating the second variant, but in the interest of historical accuracy, here is a summary of the major differences between Schlegel’s seven models, originally appearing in the Spring 1985 issue of Zeiss Historica:

-

This is an early Contax without slow speeds and a single pimple. Version 1 – Two curved round “pimples” of different sizes on the right beside the left rangefinder window. Only shutter speeds from 1/25 to 1/1000 without any grouping of speeds, squared off body with more angular edges, viewfinder window is between the two rangefinder windows, no foot around the tripod socket, and the front plate around the shutter is separate from the plate with the rangefinder and viewfinder windows. These models are usually found with serial numbers in the range of AU 80xxx and AV 24xxx. (McKeown Model A)

- Version 2 – Same as Version 1 except only one round pimple next to the left rangefinder window. The smaller pimple is missing. Serial numbers in the range of AU 8xxxx and AV 10xxx.

- Version 3 – No more pimples. Both the bezel around the shutter, viewfinder and rangefinder windows are a single piece. Very uncommon models, no range of serial numbers published. (McKeown Model B)

- Version 4 – Slow shutter speeds down to 1/2 second have been added as has a folding foot around the tripod socket to help stabilize the camera when sitting on a flat surface. The redesigned bezel from Version 3 is changed once again, this time with a curved piece that extends around the shutter speed knob. Summer 1933. Serial numbers in the range of U 21xxx and above. (McKeown Model C)

- Version 5 – A nickel plated distance scale with black numbers is added, making it easier to read. A button has been added above and to the right of the lens mount to release the infinity lock for lenses using the outer bayonet. The corners of the body are more rounded and less angular. End of 1933. Serial numbers in the range of X xxxxx to X 29xxx. (McKeown Model D)

- Version 6 – The viewfinder widow is moved to no longer be between the rangefinder windows. It is nearer the right edge of the camera. Summer 1934. Serial numbers in the range of X 61xxx to X 77xxx, Y 16xxx, Y 28xxx to & Y 36xxx, Y 63xxx to Y 65499, Z 26xxx to Z 36xxx and Z 44xxx. (McKeown Model E)

- Version 7 – A change to the infinity lock means it stays depressed whenever the lens is not at infinity and only pops back up at infinity. The accessory shoe has 4 screws and the shutter speed index is a triangle instead of a slotted screw. Serial numbers are in the range of Z 45xxx to Z 46xxx, Z 68xxx to Z 69xxx, and A 20xxx. (McKeown Model F)

- Rumored 7th/8th Version – One additional version of the Contax is rumored to have existed which contains a redesigned shutter for the Contax II which contains a faster 1/1250 top shutter speed. In the article detailing the 7 versions above, it is disputed that this final version exists, but in later classifications of the Contax that use a 6 version system, this existence of this 7th version contradicts previous information. Whether or not one final Contax I with a Contax II shutter and top 1/1250 ever existed is unclear, but if it did, then Schlegel would have likely called it the 8th version.

It should be noted that while multiple attempts to classify the different variations of Contaxes exist, there were many more very subtle differences between the different models. Some minor changes cross over from one to another suggesting that the development and design of the Contax was ever evolving.

Revisiting Schlegel’s seven version classification, the Spring 1993 issue of Zeiss Historica published seven pictorial tables from a book written by Hans-Juergen Kuc once again showing seven classifications of the Contax, the most notable difference being in the first two versions which do not agree on the number of pimples. It is plausible that this confusion is why McKeown chooses not to differentiate one and two pimple cameras into separate versions.

In 1935, Zeiss-Ikon published the a 66 page pamphlet called The Connoisseur and the Contax which served both as a catalog of the camera and it’s many lenses and accessories, but also as educational material, going into great detail about the camera’s construction and benefits. The Contax was intended for professionals who wanted the absolute best, so a little extra care went into it’s marketing, so that those who could afford one, knew it’s strengths.

PDF below courtesy of the Pacific Rim Reference Library.

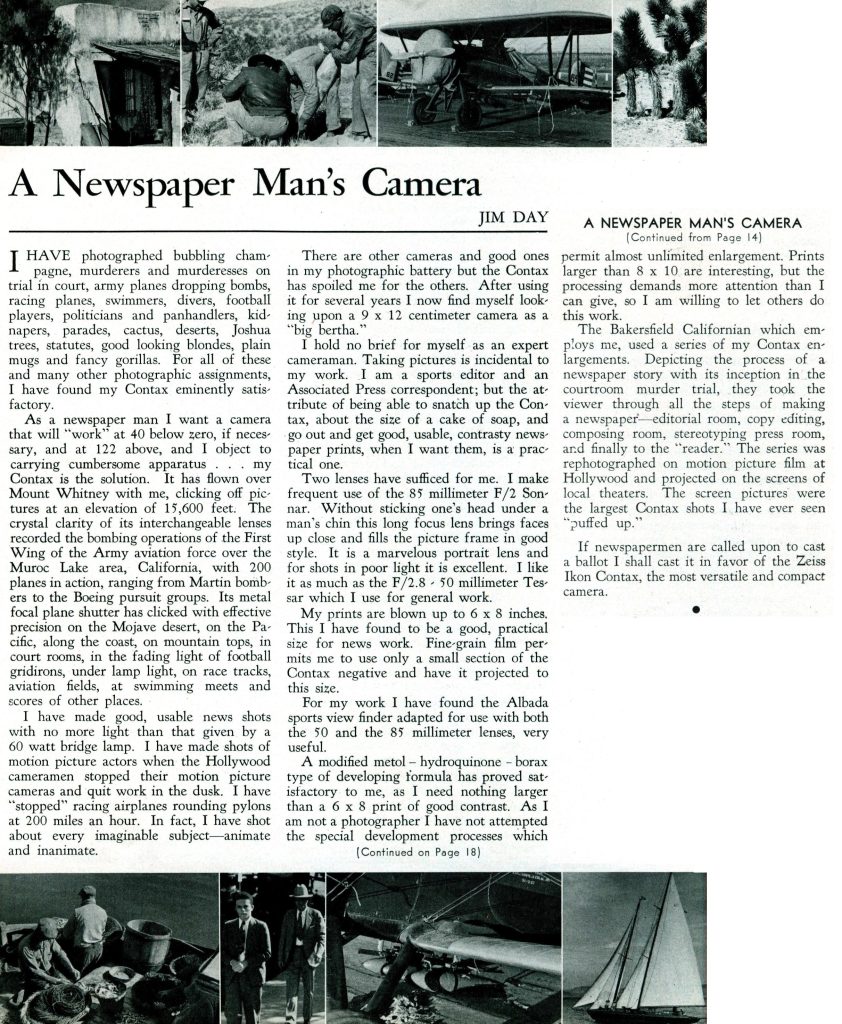

In a January 1936 issue of Zeiss Magazine, several articles were written with testimonials by various photographers who used Zeiss cameras and lenses. One such article, which appeared on pages 14 and 18 tells the story of a newspaper photographer named Jim Day and why he chose the Contax rangefinder.

It is convenient today, with the benefit of more than half a century worth of hindsight to see the Leica as the clear winner in the 1930s 35mm rangefinder wars, but to consider the Zeiss-Ikon Contax a failure is unfair. Yes, far more Leicas were sold, and yes, the Leica’s legacy has lived on much longer than the Contax’s, but for many pro photographers like Day, the Contax was not only the right choice, but the best choice. The Contax had more features, a more accurate rangefinder, better lenses, and the full support of one of the biggest names in the German photo industry.

Zeiss-Ikon was well aware their camera was expensive, and would only be considered by serious photographers with deep pockets. Most of the period advertisements for the Contax did not feature a price, instead referring potential customers to their dealers. Like most luxury items today, the thought was that the camera could sell itself, but in order to do that, they needed to get them in the hands of customers to help make the sale.

Many period advertisements used words referring to the camera and it’s owners like “masterpiece” and “connoisseur” to help drive home the point that the Contax was more than “just a camera”.

The Zeiss-Ikon Contax sold slowly, and perhaps realizing that no amount of subtle updates to the original design would get them anywhere near the Leica’s dominant market share, in 1936 Zeiss-Ikon would reboot the camera with an all new model, simply called the Contax II. For this new camera, Zeiss-Ikon handed the reigns to Hubert Nerwin.

Nerwin, an Austrian citizen was also a mechanical engineer like Küppenbender, but had no formal experience with cameras or photographic shutters prior to joining Zeiss-Ikon in 1932. Originally working in a low level position in the design department, Nerwin quickly rose through the ranks at Zeiss-Ikon due to a combination of internal turnover and his own design skills. Within a short amount of time, Nerwin found himself as the head of the design department and took on the challenge of fixing the Contax’s problems.

Without a lot of time, rather than completely designing a new camera from the ground up and requiring new lenses, the double bayonet lens mount was retained, although with some reliability improvements. The shutter would still be made of metal and travel vertically through the camera, but the whole design was changed, significantly improving it’s reliability and increasing it’s top speed to 1/1250. The rangefinder system would be changed as well, incorporating a single viewfinder window with a combined coincident image coupled rangefinder. Lastly, an all new chrome plated body that weighed less and came with rounded corners and better ergonomics was employed to address the poor handling of the original Contax.

With these improvements, Nerwin had one more trick up his sleeve, which was the addition of a second new model, this one featuring a body mounted selenium exposure meter. This metered model would go on sale shortly after the Contax II as the Contax III and would be the first electrically metered 35mm rangefinder camera. Very early versions of the Contax III were designed with holes in the front of the doors so that the meter could have a high and low sensitivity mode, but the two stage meter was quickly abandoned in favor of a simpler single stage meter with no holes in the door. A few Contax prototypes with holes in the door exist in private collections.

The updated Contaxes were a huge improvement over the previous model, but by the time of their release, with over 200,000 Leicas already sold, Zeiss-Ikon already had a long road towards competing in the premium 35mm rangefinder segment. Adding to this challenge was a large number of competing German built 35mm cameras by Kodak, Certo, and several other companies, plus growing political turmoil in Germany and a looming war, sales of the Contax II and III were still slow.

The news wasn’t all bad however, as the improvements to the Contax were not lost on those who purchased it. The convenience of the combined rangefinder, removable film back, and bayonet lens mount won over many professional photographers. Zeiss was also a more respected lens maker than Leitz with it’s Tessar, Biotar, and Sonnar formulas available in a wider range of focal lengths from 28mm all the way to 500mm. In their May 1939 catalog, Zeiss-Ikon featured 15 different lenses in Contax mount and a huge number of accessories and add-ons for macro, scientific, or other specialty work. The huge number of lenses and accessories made them very appealing to professional photographers who needed more than Leitz had to offer.

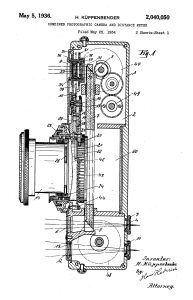

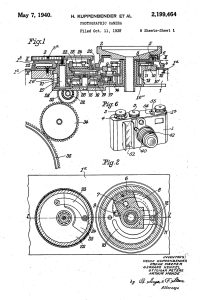

After the release of the Contax III, Kuppenbender continued to evolve his design into what would have likely been called the Contax IV, but the war in Europe put an end to any future developments. US patent documentation for a camera that likely was a fourth Contax was filed in October 1938, showing a camera with a body mounted selenium meter, a redesigned and flatter top plate, and a revised rangefinder that used external glass, similar to the company’s own Super Ikonta, Tenax II, and what would eventually appear on the postwar Contessa 35.

Patent US2199464A filed by Heinz Kuppenbender suggests future development of a fourth Contax. The drawing to the right shows an artist’s rendering of what such a model might have looked like. Although the camera was never finished, several prototype pieces matching this patent documentation and drawing do exist and can be found in the Fall 2002 issue of the Zeiss Historica newsletter.

As was the case with many prewar cameras, the start of World War II changed things. The story of the Contax name continued for quite some time after World War II as an East German SLR, a West German rangefinder, in the Soviet Union as the Kiev rangefinder, and finally, as a Japanese made SLR. This part of the story is fascinating and very deep, and something I have touched upon in my review for the Kiev IV. As this is a review for the first Contax, I won’t go any farther, only to say that the Contax story has more twists and turns in it’s history than likely any other camera.

Early Contaxes have a bit of a mystery about them. Many retrospectives have been written about them both in printed and online form about the “other” 1930s German rangefinder. Articles like the one below from the April/May 1968 issue of Camera 35 magazine are one of the earliest “looks back” at the Contax. Although printed 32 years after the introduction of the Contax II, the earlier model was likely a mystery to the magazine’s readers. By then, many likely already started to develop issues and for the ones that remained in good working order, they would have still been prohibitively expensive. As time went by, the mystique of the Contax only grew.

As early pioneers of professional 35mm cameras, both Leica and Contax rangefinders are highly sought after today for their design and historical significance. Unlike early Leicas however, there were far fewer Contax cameras made and even less still are found in good working condition today. Although it’s not fair to suggest that a Leica is a simple device, compared to the Contax, it is a much easier camera to keep in working condition. The Contax shutter is considered by many to be one of the most complex ever made, and a huge part of the reason why most technicians won’t touch them.

To get one serviced by someone like Henry Scherer, the waiting list is measured in years, and the repair bill will likely be over a thousand dollars, so if you find one for sale at a price you can afford, don’t expect it to be working, and if it is, there’s a chance it won’t stay that way for long. If, however, you are extremely lucky enough to get one that’s been recently serviced, it is a wonderful camera to hold, shoot, and display and one that I am proud to have in my permanent collection.

My Thoughts

Like any collector, I’ve been aware of the early Contax cameras long before I ever saw one. Having handled and shot my fair share of pre and postwar Contax II and IIIs, plus Soviet Kiev models, I bought into the belief that when Hubert Nerwin came up with the Contax II and III, it was a significantly better camera. In many ways it was, but if the new models were so much better, then the original ones had to be “less good”, right? A squared off body with sharp corners, strange ergonomics, and a poor reputation for reliability made me think that shooting an original Contax I would be a miserable experience.

The first time I ever handled an original Contax was while visiting my friend Ira in the summer of 2021. He had two versions, an early one with two little bumps next to the rangefinder window, and a later copy without them. Handling both cameras, I remarked at how nice they felt in my hand. I’m no stranger to brick-like cameras as I have a well documented fondness for the Argus C-series, and like those cameras, the 90 degree corners of the Contax body didn’t bother me at all. Compared to a prewar Contax II, the two cameras are nearly identical in width with the Contax I about 2mm shorter. Although this might not seem like much, in reality, the shorter top plate gives the camera the illusion of being smaller. On a scale, the Contax I is also about 20 grams lighter than a prewar Contax II, but I could not detect that holding both in person.

The camera has some oddball controls for sure, as winding the front mounted knob to advance the film transport is not usual, and the camera’s system for changing shutter speeds is as about as bizarre as I’ve ever seen, but that initial experience with the Contax left me impressed. This was not at all the type of miserable failure that I had come to believe after reading of Nerwin’s significant redesign of the camera in 1936.

I was hooked. Normally when I have a GAS attack for a particular model, I consult my own reference guide for buying cameras on eBay. In this article, I detail several ways in which I have been able to pick up cameras at discount prices, but I felt that no amount of patience would get me a working Zeiss Contax I in my typical price range.

Through talking to a couple of collectors, I finally came across a really nice looking model that had recently been CLAd by Radu Lesaru at 3RCamera in Naples, Florida. The price was still high, but after a short blitzkrieg of trades and selling a few of my less loved cameras on eBay, I was able to work out a price I could afford for the Contax.

When I first started getting into collecting cameras, I was frequently blown away by the condition and quality of early cameras. The first time I held a Barnack Leica, a Nikon rangefinder, and a Rolleiflex, I was amazed at the heft, the intricacy of the controls, and the feeling of quality these old cameras exuded. Sadly, as I’ve handled more and more cameras, I became spoiled. It became harder and harder to impress me because of how many amazing cameras I was handling. To be clear, I’ve loved almost every camera I’ve ever come across, it’s just that there’s so many of them out there, the bar keeps getting raised.

When the Contax showed up and I took it out of the box, I experienced that feeling of amazement for the first time in a while. I couldn’t remember the last time I was this impressed holding a new (to me) camera. This one was nicer than either of the two Ira owned. The black enamel was in excellent condition, showing very few scratches or chips. It was so shiny, I could see my reflection in it. The nickel controls looked brand new, the body covering was in excellent shape, not peeling or showing any tears or cracks like you might expect from a 1930s German camera, heck, there weren’t even any Zeiss bumps! It was as if this camera traveled through time from the 1930s to me!

Up top, the Contax is covered in the same material as the rest of the body, with a black and nickel plated two tone finish to the rewind knob and accessory shoe. The rewind knob has an arrow to indicate the direction it should be turned, but otherwise works as you’d expect. The Contax offers no built in flash synchronization so the accessory shoe would most likely be used with auxiliary viewfinder, or with a shutter release controlled flash gun.

On the right side is a rather large nickel plated shutter release with a threaded cable release socket. The location of the shutter release is closer to the front edge of the camera than found on Leicas of the same era. While I won’t say the location of the Leica’s shutter release is uncomfortable, I find the location of the shutter release on the Contax to be more intuitive and comfortable for my hand. In front of the shutter release is the fine focus wheel and focus lock release which serves the same purpose as on later Contax rangefinders, along with the Soviet Kiev and Nikon rangefinders. Finally, the additive exposure counter is on the far right showing how many exposures have been made. The counter must be manually reset after loading each new roll of film.

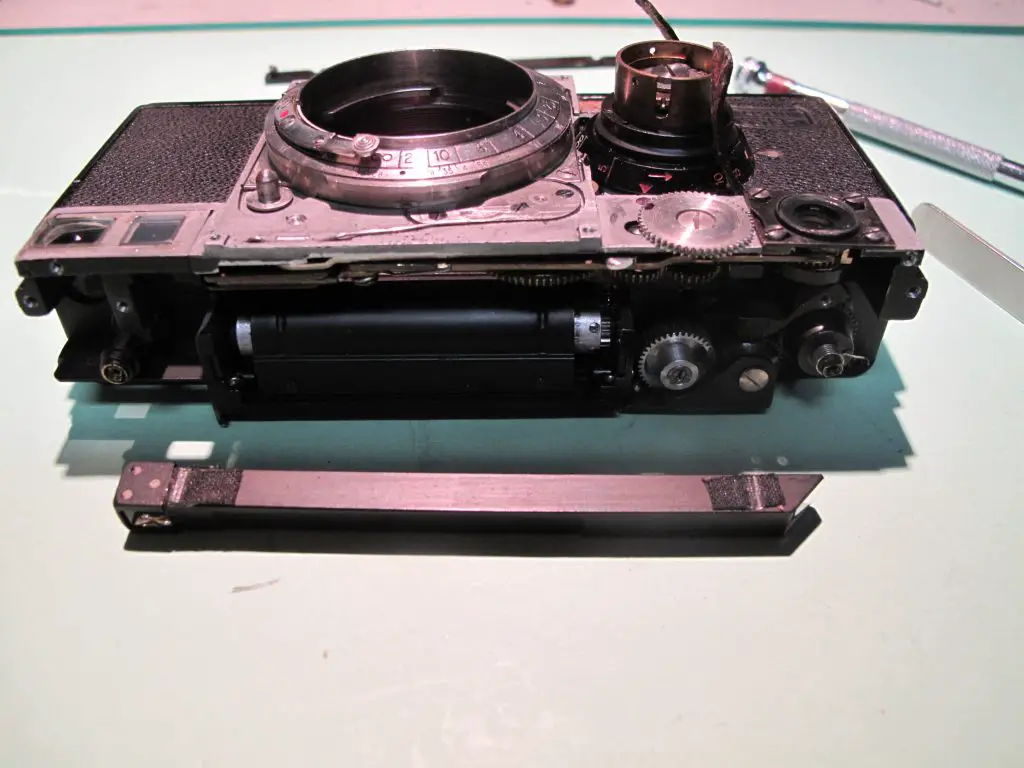

Flip the camera over, and there are two raised feet which double as the film back and cassette locks. With the handle of both locks folded towards the center of the camera, the back is secured and reloadable metal cassettes are open, with the handles facing the edges of the camera, the back can be slid off and the film cassettes are closed.

In the middle is a square plate with the 3/8″ tripod socket in the center. This size socket was common on European cameras of this era and would not be compatible with modern 1/4″ tripods without an adapter. Around the edge of the tripod socket is a folding foot which first appeared on Version 4 Contaxes, which helps balance the camera with a lens attached, when set on a flat surface. Finally, to the left of the tripod socket is a film transport lever which when the letter “V” is visible, film transports normally, but when moved to reveal the letter “R” disengages the transport for rewinding film.

Around back are the two circular openings for the viewfinder and rangefinder in the upper left corner, and a metal slider which is used to disengage the exposure counter so that you can reset it to ‘0’ after loading in a new film cassette. The rear body covering is mostly empty, save for an embossed Zeiss Ikon logo in the bottom right corner.

Each of the two sides of the camera are the same, with little to see other than a shiny metal square shaped strap loop which hangs from a screw in the side of the body. Earlier versions of the Contax had more squared off edges, but this being a later model, they are more rounded. From the camera’s right side, you get a side profile look at the combined film advance and shutter speed knobs.

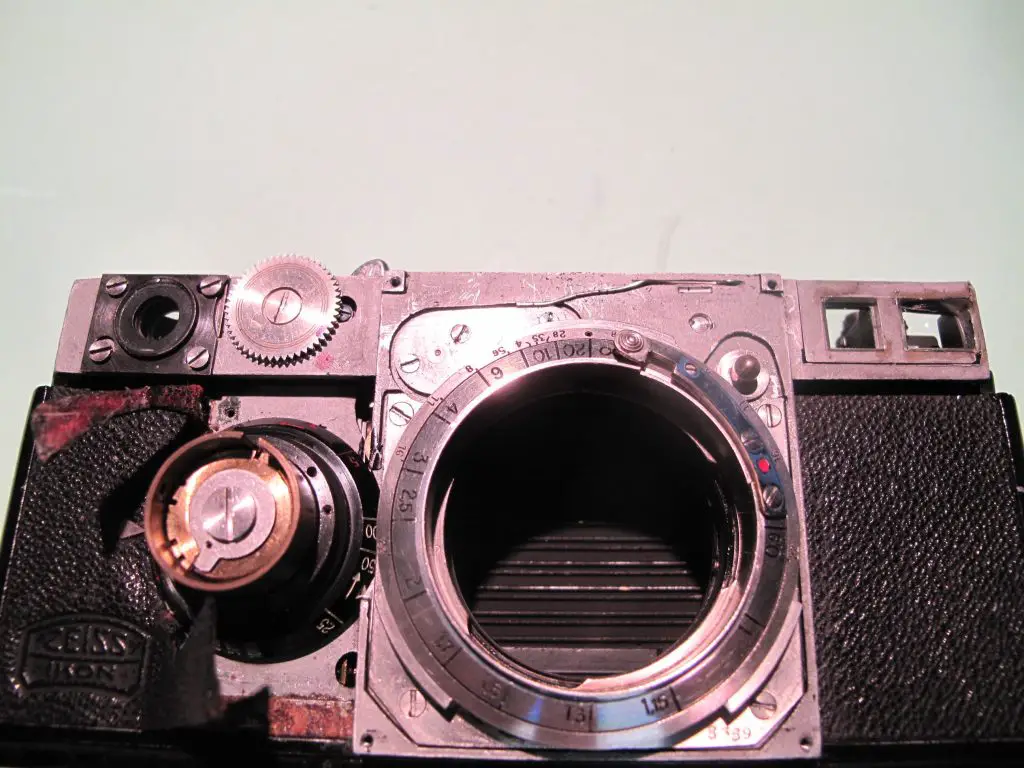

After removing the film back, the film compartment is surprisingly modern. Comparing the Contax I to a postwar IIIa, very little has changed. It is clear this was one area of the camera where Nerwin didn’t have to do much. Film transports from left to right onto removable spools or in a cassette to cassette system. The most distinctive thing you’ll see in the back of a Contax are the metal horizontal slats of the shutter. This shutter design is vertical, allowing for a shorter overall distance for the curtains to move. Plus, the curtains being made of metal made them more durable, both to accidental touches, but also resisting pinholes common with cloth curtains. These are nice benefits, but they come at the cost of the Contax having one of the most complicated shutters ever devised for a 35mm camera. Repairing a Contax shutter, whether it’s an original model like this one here or a later IIIa is not for the faint of heart, and something that very few technicians today are willing to do.

Note: The previous image to the right of the film compartment (and one with the lens removed later in this article) were taken before the camera had been CLAd. You can tell as the slats on the shutter are at a slight angle, indicating the straps were loose. This has since been repaired and the slats are now parallel, as they should.

The inside of the door has a black painted metal pressure plate, and a metal roller on the take up side which helps maintain film flatness as it travels through the camera. The inside of the film door, and on the bottom of the inside of the shutter gate have the camera’s serial number. When these cameras were built, the backs were hand formed to each body, meaning that only with the original back could light tightness be guaranteed. As a collector, you’ll want to confirm that a camera has it’s matching back, or else it’s value can be negatively affected. As is the case of all Zeiss-Ikon cameras of this era, the first letter of the serial number is a date code. Mine has the letter Z, which means it was built in either late 1935 or early 1936. If your camera has two letters, that means it was sent back to the factory for upgrades at a later time and a second letter stamped.

Both the original Contax and Leica Model A predate Kodak’s type 135 daylight loading cassette, so it’s impressive to me to see how similar the entire Contax film compartment is to later cameras. I’ve seen more variation in film compartments from cameras in the mid 20th century than on this camera. It is clear that these designs were the template that pretty much everyone else used for their 35mm cameras.

Up front, the Contax has a dual bayonet lens mount. Unlike the Leica Model C which used a 39mm screw mount which requires each lens to have it’s own focusing helix, the Contax has it’s own focusing helix connected to an internal bayonet, built into the camera, but only for 50mm lenses. This means that 50mm Contax lenses can be smaller and cheaper to construct as you do not need to include those parts on every single lens. When installing a lens of any other focal length, they need to bypass the internal bayonet and instead connect to an outer bayonet. Doing this covers both the internal helix and focus scale on the front of the camera, instead using one on the lens itself. Although complicated, this was a genius move, allowing for a best of both world situation.

The mount on this camera is nickel plated, which I prefer over the chrome plated ones on later Contaxes, and has a distance scale indicated in meters only from 0.9 to infinity. A depth of field scale from f/2.8 to f/22 is also engraved, not having any marks for f/2 or f/1.5. By far, my least favorite aspect to the Contax mount is the little metal lever that you have to press in with the tip of your finger to release and install the lens. I’ve never liked this design on any Contax, Kiev, or Nikon camera I’ve used.

Above and to the right of the lens mount is the infinity lock, which must be defeated by either pressing the lock up and to the right, or by using the little button next to the fine focus wheel on the top of the camera. In the upper right corner, in front of the main viewfinder and one of the rangefinder windows is a sliding mask for 8.5cm lenses. Not that I have one, but had I had a Contax lens in this focal length, you could still use it without needing an auxiliary viewfinder.

So far, most of the Contax’s operation is pretty self explanatory. Anyone who has handled a prewar 35mm camera should be able to pick one up and figure out how to use it without a manual…that is until you get to the shutter speed knob.

Before I continue, I’ll tell you I actually like this part of the camera, it is just something you really need to pay attention to. For starters, the thicker, outer portion of this knob operates the film advance, cocks the shutter, and advances the exposure counter with a single twist. Having the knob on the front face of the camera isn’t any less convenient than having one on the top plate of the camera, in fact, the larger diameter of the knob makes gripping it and giving it a secure twist in one smooth motion, easier. After firing a shot, take the camera down from my eye, reposition my right hand on the knob, give it a twist, and put it back to where it was. Having it on the front is not a problem.

Beneath the knob however is a second knob, and beneath that is a black ring that depending on the position of the second knob, shows you a couple of different shutter speeds. This version of the Contax I has ten shutter speeds from 1/2 to 1/1000 plus Bulb, but you will never see all ten at the same time. Shutter speeds are selected in groups, which are determined by the position of the second knob. A metal triangle arrow on the front face of the camera should always line up with either a red or white painted triangle on the black dial allowing you to see one of the following four groups:

- Group 1 – B, 2 (Use Red Dot)

- Group 2 – 5, 10 (Use Red Dot)

- Group 3 – 25, 50, 100 (Use White Dot)

- Group 4 – 100, 200, 500, 1000 (Use White Dot)

Warning: A down facing arrow next to each group indicates the direction you must rotate these groups in. Do not try to turn the dial in the opposite direction! If you miss a speed, rotate it all the way until you get back to the group you want. Always make sure the metal triangle on the front of the camera is pointed to one of the 4 triangles for each of the four groups. The number 100 for 1/100th of a second is the only one that appears in two separate groups.

Changing the speeds requires pulling the film advance knob away from the body and rotating it, until a white dot aligns with your chosen speed on speeds 1/25 and up, and a red dot on the slower speeds. When selecting a speed below 50, there will be additional resistance from the slow speed governor as you rotate the dial. This is normal. In the image to the left, the white dot is aligned with the line pointing to 1000, indicating I have selected a shutter speed of 1/1000.

If this sounds complicated to you, I made a short video, showing me rotating through the four groups, selecting a couple of different speeds. One last word of caution is that the only reason each of these speeds works correctly on this camera is because it was recently CLA’d. I would expect a large number of Contaxes found in the wild have inoperable shutters, or at least slow speeds, causing these actions to be difficult, and possibly dangerous to attempt.

Around back, the Contax has separate viewfinder and rangefinder windows, much like rangefinder cameras of the era did. For those used to more modern rangefinder cameras with combined image coincident image rangefinders, having the rangefinder separate from the main viewfinder often seems like a chore. A combination of a small size, plus having to move your eye back and forth to focus and compose can easily seem archaic to someone who is not used to it.

For sure the openings are tiny, but there is one major advantage to having the rangefinder and viewfinder separate, which is what they can have different magnification ratios. All viewfinders, whether SLR or rangefinder have a magnification ratio which is a measurement of how the image appears compared to real life. A viewfinder in which the image is the exact same as life size, is said to have a 1:1 ratio. This is ideal for those who like to keep both eyes open while composing their shot, but is not ideal for the actual rangefinder as in order for the coincident images to line up, the rangefinder also has to be 1:1.

When you separate the rangefinder, it can be magnified separately from the viewfinder, allowing the rangefinder image to be more precise, giving you a greater degree of focus accuracy than if it was in the center of the main viewfinder image. This is especially useful when shooting telephoto lenses as critical focus gets harder to achieve the longer the lens is. In the case of the Contax, the rangefinder patch is roughly 1.5x that of the viewfinder, meaning you see a much larger and easier to focus image through the rangefinder. Once you’ve achieved proper focus, move your eye over to the main viewfinder and compose your image. This certainly does slow you down a bit, but once you get used to it, it’s not that much slower, but the upside is that you have a much easier to use rangefinder.

The Contax’s use of a glass prism instead of mirrors separated by air, mean that the chances that the rangefinder becomes misaligned is reduced as there’s less moving parts or pieces of mirror to break away. Furthermore, prism rangefinders are less likely than mirrors to show haze, which reduces contrast on many cameras with that style.

The rangefinder is tinted yellow and shows very good contrast. The entire rangefinder patch takes up almost the entire view through the rangefinder window and shows only a central portion of the image the camera is pointed at. In order to see the entire composed image, you must move your eye over to the viewfinder window on the left. Inside the viewfinder, there is nothing to see, no projected frame lines or information about exposure.

The main viewfinder approximates a 5cm image but if you have an 8.5cm lens mounted, a mask on the front of the camera can be slid over the viewfinder window to reduce it’s size, approximating the view through an 8.5cm lens. This doesn’t take the place of a dedicated viewfinder, but would work in a pinch.

It is not often that I comment on camera cases in my reviews as most of the time they’re in such poor shape or smell so badly that they get tossed into a corner of my basement never to be seen again, and of the few that are in good shape, aren’t that remarkable.

The Contax however came with one of the nicest ever ready cases I’ve ever seen, made of the thickest, most supple and luxurious leather I’ve ever seen or touched. The front snout of the case has a very large and thickly embossed Zeiss Ikon logo which owners of this camera would have proudly displayed much in the same way someone would be proud to show off a Louis Vuitton or Prada handbag.

The thickness of the snout is shallow, only allowing for a collapsible lens to be mounted. Whoever bought this camera would have not been able to use it with a non-collapsible lens in any focal length, somewhat reducing the usefulness of the case, but with the collapsible Tessar lens, works really well. The entire case is still in great shape with only a few missing stitches.

The back has painted on it a name that looks like “Albert D Polak” who I can only assume was the camera’s original owner. The letters of the last name are worn off, so I might have the spelling wrong, but a Google search for the name in various spellings didn’t turn up anyone.

There is a ton to like about the Contax. As was explained in the history section above, the Contax was developed to be a world class professional camera with all of the features a pro would need. It’s ergonomics and control layout are unlike any other camera ever made, so the first time user would be well served by reading the manual (or this review) before trying to shoot film in it.

Despite what you may have read online though, in my time handling the camera, I never found it’s controls to be that difficult to use. Different yes, but not anything that you wouldn’t get used to quickly. But of course, that’s all great, what is it like to shoot?

Repairs

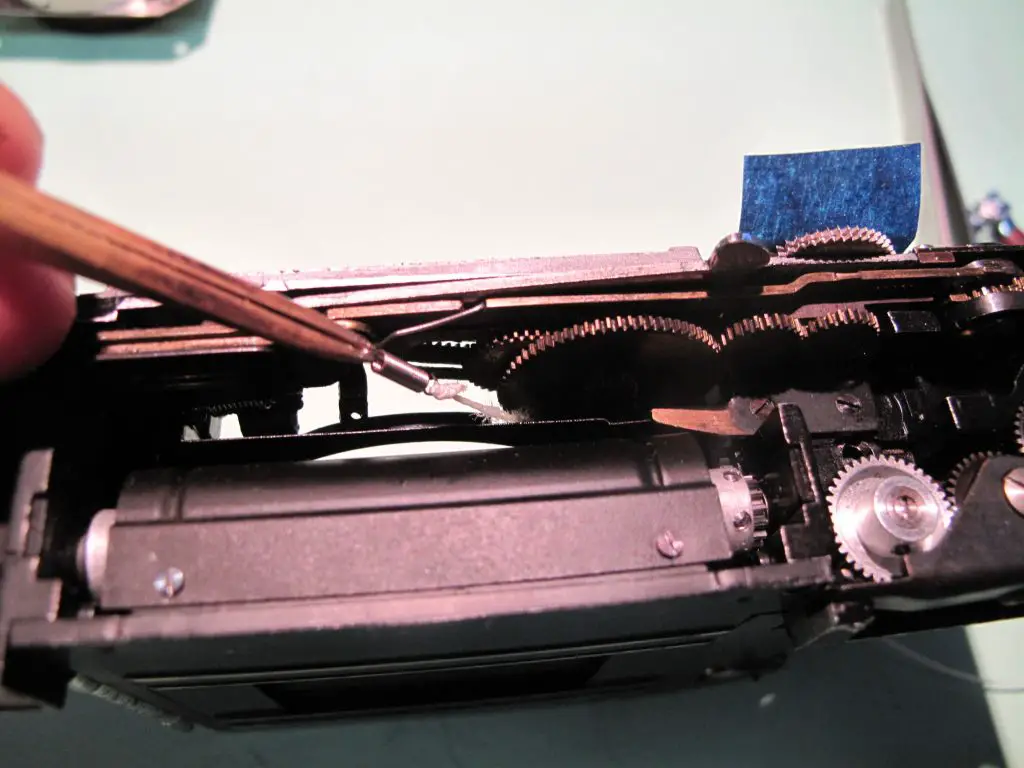

Like nearly all Contax I cameras that have survived the past 85-90 years, this Contax I fell into disrepair, with shredded shutter straps, a gummed up shutter, dirty viewfinder, and a whole host of other problems. Today, you often hear the statement, “they don’t make ’em like they used to” when it comes to our planned obsolescence of electronics that are thrown away once they reach their end of life.

To be sure, items like cameras aren’t made like they used to be as they can last a heck of a lot longer than a modern digital camera or smartphone, but in order for that to happen, they need regular service. You wouldn’t expect to buy a new car from the dealer and never have to change it’s oil, brakes, suspension, or give it a tune up every now and then, would you? Cameras are the same way. When original Contax and Leicas were purchased in the 1930s, the owners would regularly take them in for service to keep them in tip top shape.

The challenge with cameras like the Contax however, is that they require a very specialized skill set to repair. Not only that, but replacement parts are no longer being made. If something were to break, you either need to fabricate or repurpose something from something else and make it work. These were complex devices that weren’t easy to fix in the 1930s, and over the past several decades, the number of people willing and able to service these cameras has dramatically decreased.

Today, guys like Henry Scherer at zeisscamera.com will still take them on, but his turnaround time is very long and his prices are indicative of the rarity of his skill set. For a more affordable option, Radu Lesaru at 3RCamera in Naples, Florida will still repair Contaxes. While Radu does not specialize in Contax, he is a factory trained tech formerly working for Karl Heitz, repairing Alpa and Tessina cameras. Radu will take on challenges most other techs won’t touch, and this Contax I was one he agreed to service.

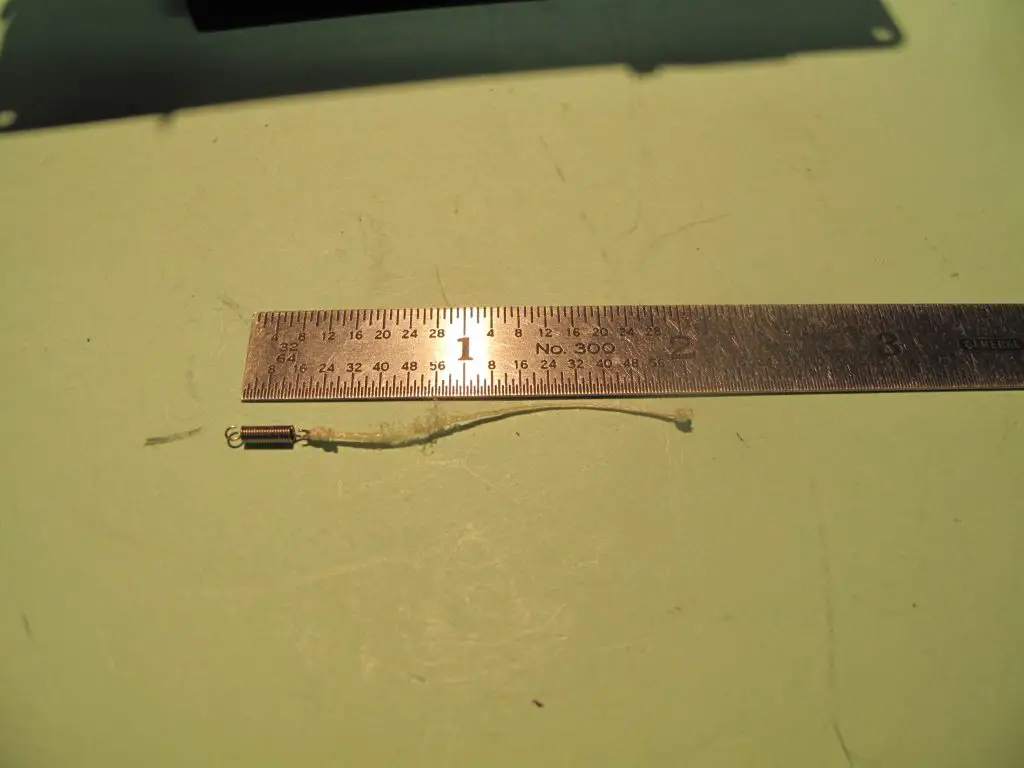

When it came to him, the camera was in nice cosmetic condition, but the silk shutter straps had torn, the viewfinder was very dirty, the focus helix was stiff, and the shutter’s slow speeds were inoperable. When he took it apart, he found two more problems, one that a rubber bushing had cracked and needed to be replaced, and a string that couples the rangefinder to the lens mount was heavily frayed and nearly broke. Both would need to be replaced.

The entire CLA took over 4 months to complete, at which time both silk shutter straps were replaced with modern equivalents, the rangefinder and viewfinders were cleaned and adjusted, the rangefinder string was replaced, the rubber bushing was replaced, the entire shutter and slow speed assembly were cleaned of grime and rust, and lubricated and adjusted, the focus helix was cleaned and lubed, Zeiss bumps on the back door were removed and the body covering reglued, and finally a missing screw on the bottom foot was replaced.

The camera’s physical condition was now on par with it’s cosmetics. While there’s no way to track how many fully functioning Contax Is are out there today, I have to imagine that finding another example like this is extremely hard to do.

My Results

Eager to see what the CLAd Contax was capable of, but also running low on color 35mm stock, I chose some expired Kodak Plus-X for my first roll and shot a quick roll around the house, just to make sure the camera was working and to acquaint myself with it.

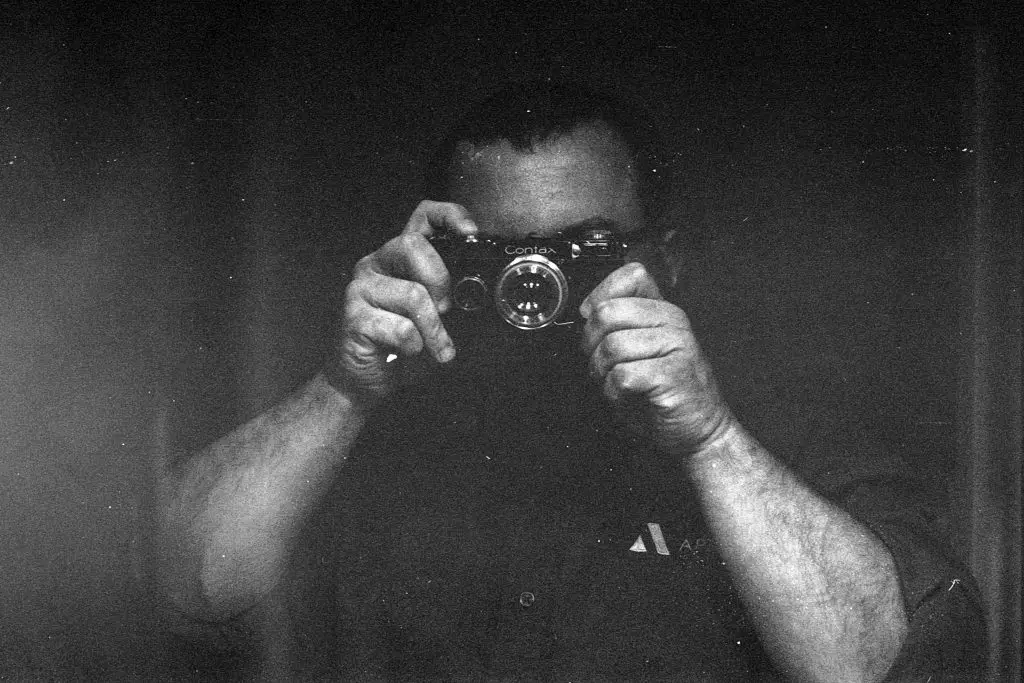

Because I am an idiot and don’t write things down, shortly after loading in that test roll, I forgot what film I had in it and exposed the entire roll as if it was what I thought was Fuji Neopan 400 and underexposed many shots, including the mirror selfie above. Of the ones that did come out however, I was very pleased with the results, proving that the CLA had worked. The shutter was firing well and the rangefinder was accurate. Sadly, the lens that came with the camera had quite a few scratches on the front element that Radu was unable to fix, so combined with the uncoated prewar optics, there is quite a bit of softness in scenes where sunlight was present.

Satisfied that the camera was worthy of capturing memories on a family trip to Mackinac Island, Michigan, I loaded in a roll of Kodak TMax 100 and made sure I remembered what was in there! For this trip, I mounted a Soviet Jupiter 8 lens that I’ve shot before on a Kiev rangefinder and knew it to be optically excellent.

Reasonably sure the images would turn out nice, but still on edge as I had felt I got some great images with the camera, I held my breath with a tad bit of anxiety as I opened the lid to the Paterson tank to see these images for the first time.

To my complete satisfaction, nearly the entire roll was perfect. Out of a 36 exposure roll, I missed focus on maybe 2-3 images and had one shot where I clearly wasn’t paying attention, but otherwise I had an entire roll of some of the best images I had ever shot. To some, that I used a Soviet lens on a CLAd Contax I might seem like heresy, but that the Jupiter 8 is a direct copy of the Biotar and this example had a 1955 serial number and possibly was made with some genuine Zeiss parts, it was an acceptable compromise to me.

By this point, I was pretty happy with the camera, but wanted a better example of the Tessar lens, so as he so often does, Paul Rybolt came to the rescue with another collapsible f/2.8 Tessar lens that was in better shape than the one I had, so I took off the Jupiter, attached Paul’s Tessar and loaded in a “freezer fresh” roll of Kodak Porta 160 VC and took the camera out for it’s third roll.

Where do I start?

I’ve already proclaimed that the Contax impressed me more than I thought it would. The things I had read about it having poor ergonomics and a finnicky operation were largely incorrect. Sure, the camera has squared off edges and a strange front film advance with combination shutter speed dial, but I found these to be no more of a hassle than a top film advance and shutter speed dial. In fact, whatever unfamiliarity I had with the location of the film advance was offset by it’s large diameter which was easy to grip and spin with a single motion of my wrist.

The clean and adjusted rangefinder and viewfinder windows were excellent to use and allowed me to compose and focus my images in all sorts of lighting. The focus helix was properly lubricated and easy to turn, even with the precision wheel which on many other cameras with this feature usually end up sawing through the skin of my finger due to stiffness.

And then there’s the lenses. I shot three rolls of film with three different lenses. Commenting on the two Tessars, I know there are a lot of people who are disinterested in Tessars because of how common they are. How good could a 4-element lens be, they say?

Hella good, I say! There is a reason the Tessar is the most widely copied and mimicked lens formula of all time. There is a reason that for well over a hundred years, people have been putting Tessar formula lenses on everything from large format portrait cameras to cell phones. It works, and it works REALLY well.

The image quality I got from these rolls was top notch. The second Tessar was in better shape, but let’s be honest, the Jupiter did an outstanding job too. Part of me would like to source a nice early Sonnar, but frankly, I’ve already spent enough money on this camera. Between the Tessars and Jupiter, I’m set for 50mm Contax mount lenses. Whatever I get next will have to have a different focal length.

Maybe because I had an expectation that the Contax was going to be a difficult and finnicky camera before ever shooting it positively tainted my opinion of it. If you think you’re going to hate something before trying it, you’re much more likely to be impressed if your fears never come true, but maybe the Contax was really that good. If I had to complain about one thing, it would definitely be how shutter speeds are selected. While I guess on one level, it makes sense to group similar shutter speeds together, the way Zeiss-Ikon designed it on this camera is completely unnecessary. Sure, they technically could say it’s all on one dial compared to the Leica III and many others which had separate fast and slow speed dials, but the complexity of the Contax’s system does not in any way speed things up.

Beyond that though, the Contax I was a very enjoyable camera to use. It felt different enough to feel old, but not so foreign as to disrupt my ability to use it. Like any old camera, I needed to take a minute or two to familiarize my controls before shooting it, but after a few minutes, it’s operation became intuitive to me.

Coming back to the very beginning of this article where I claim that people have been comparing Leicas and Contaxes since 1932, and now having shot a perfectly working 1930 Leica Model A and a perfectly working Contax I, I am in the unique position for an Internet blogger to have shot both, so how do they compare?

Well for starters, both are outstanding cameras that deserve nearly a century’s worth of respect and adulation, however both cameras are very different. It is clear that Heinz Küppenbender produced a different kind of camera. Where the Leica’s lens mount was a simple screw mount and it’s rangefinder used mirrors separated by air, the Contax was a precision machine with a state of the art shutter, an all glass prism viewfinder, and a complicated dual bayonet lens mount. Carl Zeiss was the undisputed king of lenses back then and the Contax was built with those lenses in mind.

While the Leica was no slouch, it was a simpler camera, designed for simpler operation. The Model A I had lacked a rangefinder, so I was able to use zone focus and shoot it from the hip. I felt more causal in my use with it, getting candid shots that a camera which requires calculated precision might not have been able to capture. For me, I found the use of the early Leica to be fast and spontaneous, and my images reflect that. With the Contax, it feels like you are using a precision instrument which demands your attention and complete focus, and I think my images reflect that as well (well, at least some of them do).

Which is better you ask? I’m gonna take the easy way out of that question and answer it with, it depends on what your priorities are. You don’t need me to tell you the Leica outsold the Contax and was far more successful by orders of magnitude. There was no shortage of professional photographers who used Leicas to great effect, capturing some of the nicest images ever made. The Contax on the other hand, was almost entirely rebooted in 1936 with the release of the Contax II and III, and never reached the sales success of Oskar Barnack’s design.

But once again, that’s not the point of the Contax. This is a world class instrument that used the finest lenses available, and while the shutter was difficult to work on, when it worked, it WORKED! I loved my time with the Contax and am absolutely thrilled not only to have a chance to shoot one, but also to shoot one that’s been professionally serviced and hopefully will give me many more years of enjoyable operation to come.

The camera isn’t perfect, but that’s OK, it doesn’t have to be. This is a 90 year old camera after all. Sure, Zeiss made optically more interesting lenses than the Tessar, and perhaps with some more experience, the camera’s slow operation will wear thin with me, but as I write this, several months after shooting that first roll of Plus-X, I am still enamored by it.

Quite simply, the Contax is my favorite 35mm camera in my collection and one I will come back to far more often than the Kodak Ektra or Leica M3 that sit next to it on the shelf.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Contax_rangefinder

https://www.cameraquest.com/zconrf1.htm

https://www.pacificrimcamera.com/pp/zicontax1.htm

https://cameralegend.com/tag/contax-1-review/

https://antiquecameras.net/zeisscontaxrflens.html

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/appareil-12046-Zeiss%20Ikon_Contax%20I.html

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C435.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/zeiss-ikon-contax-i-collector-interest-or-value.5519448/

Another Top Gun review, Mike – we learn a lot from you when you get your hands on a true classic like this. Thanks also for the name of Radu Lesaru, new to me but an addition to the list of reliable repairmen still working.

You mentioned a string connecting the rf to the lens mount. Don’t some of the Nagel-built Retinas have a similar, and equally troublesome, design?

Roger, I don’t know about Retinas in general, but I was told by Chris Sherlock, the well-known Retina guy (since retired, I gather) that the Retina Reflex III has a somewhat convoluted cord path for connecting and synchronising the shutter to the exposure meter. Not to be messed with by the inexperienced!

Roger and Terry, you are both right, the Retina Reflex, and I believe the Retina III S have a wheel at the bottom of the lens mount, which is connected to the exposure meter on the top plate of the camera via some kind of nylon string. I have a picture of one in the Repair section of my review for the Retina Reflex IV. I’ve actually spoken to Chris about this and he says the string is surprisingly strong and usually doesn’t snap on it’s own. Where you run into problems is when the old lubes dry and things no longer turn as smoothly as they once did, and continuing to operating the camera like that stresses the string and it starts to rub on things and will eventually break. It seems as though Zeiss did something similar with the Contax, except they used it for the rangefinder, rather than an exposure system like Nagel did.

Great review, Mike, with plenty of historical background. I well understand your anticipation when unboxing. The same happened to me when I received mine; I can’t think of any other camera that I’ve bought that I so eagerly awaited to get it in my hands. Mine came from a trusted seller in Germany and was sold as a V.7 Export model. I gather this refers to the focus scale being in feet and “Made in Germany” on the black disc in the centre of the frame counter.

Rather interestingly, the odd arrangement for setting the shutter speeds was carried over to the post-war Contax slr. Not directly equivalent, but there is a slider switch on the rear of the top housing to select slow speeds or fast. The speeds are intermingled on the speed dial and are colour coded, red(slow) and black(fast). This switch brings into play a red or black arrow placed at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions around the shutter dial. Only the speed range selected will correctly aligh with the appropriate arrow marker.

I doesn’t look like you are that interested in complementing your Contax 1 with an f1.5/Sonnar, but if you do get the itch for one, a “period” example lens only stops down to f11, and takes 42mm push on filters.

This was a really interesting article on an all time classic. I own a later one. Well done Mike.

Excellent Article! I enjoyed reading it and the videos were very interesting and informative. Thank you!