This is the Comet, an inexpensive mostly plastic camera sold by the Zenith Camera Corp of Chicago Illinois, starting in 1947. The Zenith makes eight 4cm x 6.5cm images on 127 “vest pocket” roll film. Although resembling many very cheaply made, simple cameras that were popular in the late 1940s, the Zenith is unique in that it has a full focusing lens from 2 feet to infinity. By moving the entire shutter and lens forward and back along a painted scale, the camera has a level of flexibility not common in it’s market segment. The unique, through the body optical viewfinder is a nice touch as well, suggesting the Comet was created as a step up camera from other cheap cameras.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (eight 4cm x 6.5cm exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown Focal Length f/11 uncoated meniscus

Focus: 2 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Built In Polished Glass Scale Focus Viewfinder

Shutter: Metal Blade

Speeds: Instant and Bulb

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 205 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/comet_camera.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zenith Comet is one of many inexpensive, mostly plastic cameras built to use 127 roll film in the years before and after the war. At first glance, there isn’t anything special about it until you see it’s through the body viewfinder and full focus lens. The images the camera make are technically terrible, but have a distinct vignetting that gives a look that some people work very hard at to fake. This is an immensely fun and easy to use camera that turns out to be one that you’ll likely want to keep coming back to, even though you might feel a little guilty about. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for indescribable coolness, the images come out terrible, but in an awesome way! | ||||||

| Final Score | 6.2 | ||||||

History

In the 1930s and 40s, if you were a professional photographer and you wanted a professional camera, you bought something made in Germany. If you weren’t quite a pro, but wanted something American made, but still pretty good, your camera was likely made in New York or Michigan. However, if you just wanted the cheapest possible camera money could buy, your camera likely came from Chicago.

Chicago-made cameras from the 1930s and 40s were sold under a dizzying number of names such as Spartus, Falcon, Acro, Pickwick, Remington, Minicam, Candex, Elgin, Clix-O-Flex, and many, many others. Despite the huge variance of names, nearly all of them were the work of one man, Jack Galter, who I covered quite extensively in my review for the Falcon Super Action Candid.

While we know a lot about Jack Galter and his many endeavors, we don’t know everything. Making matters more confusing is that due to the nature of his cheap products and sometimes questionable business practices, not a lot of detailed records were kept, which makes the history of Chicago made cameras confusing.

So when you come across a cheaply made, plastic camera from the late 1940s, it’s easy to assume that it was just another in Galter’s empire, but from what little I can find online, I don’t think the Zenith Comet was one of Galter’s brands. The Zenith Radio Corp, who went on to greater success in the radio and television industries, was also based out of Chicago, and considering that other radio companies like IRC (Argus) and Detrola also ventured into cameras, it’s not a stretch to think that Zenith Radio also dabbled with cameras too.

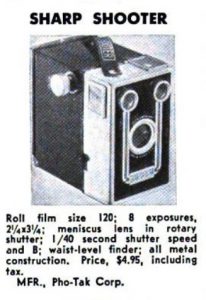

Perhaps the best clue as to who made the Zenith Comet comes from a different camera also claimed to be made by the Zenith Camera Corp of Chicago, the Zenith Sharpshooter. The Sharpshooter was a very basic 6×9 box camera available in the late 1940s and early 1950s, about the same time as the Comet.

The camera appeared in Popular Photography’s 1950 Directory of Photographic Equipment in their May 1950 issue. On page 111 is the short blurb to the right which credits the Sharpshooter as being made by Pho-Tak Corp.

Pho-Tak was yet another Chicago based maker of cheap cameras, just like Jack Galter’s many companies. And like Galter’s companies, Pho-Tak used a variety of different names, one of which was the United States Camera Corp, or USC for short.

Both located on 17 North Loomis St in Chicago, both Pho-Tak and USC produced a huge number of different cameras sometimes recycling names. What really gives this theory credibility is that USC would at different times make at least two different cameras with the name “Comet”. The first was a cheap folding camera that appears to be based off the Pho-tak Foldex 6.3 and the second a plastic 127 box camera with an integrated flash.

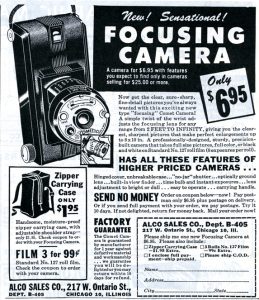

Whether or not Jack Galter, Pho-Tak, USC, or Zenith Radio made the Zenith Comet or not is not certain, and sadly, that’s all I know. In my efforts to research this article, I could not find anything more definitive. Even the ad to the left, which shows the list price of the Comet as $6.95, shows that it can be bought from the Alco Sales Company of Chicago, not Zenith themselves.

When adjusted for inflation. the price of $6.95 compares to around $80 today, which is below the price of any commercially available camera you can buy now, suggesting that even in 1947 when this camera was first sold, it was considered to be a very low end model. The Zenith Camera Company made a few other models, in addition to the Comet, but they were all very cheap entry level models.

I do not know how many Comets were ever made, how long they were produced for, how they were sold, and what became of the company after they stopped. The only thing I can tell you for certain is that they did exist, and I have one.

Today, cameras like the Zenith Comet require a very specific type of collector. Their value is extremely low, but therein lies the (limited) appeal of them. These cheap cameras were extremely plentiful and if you like variations on a theme, inexpensive mid century plastic cameras are great to collect. They’re not expensive, and for anyone crazy enough to run a roll of film through them, can deliver unexpected results that some people enjoy.

My Thoughts

As photography became more and more accessible in the 20th century, there were no shortages of inexpensive cameras that were aimed at the very basic consumer. Some people just wanted to capture a photograph and they didn’t care how good of an image it was. Eastman Kodak’s first Brownie camera was the first truly successful attempt at dumbing down photography to the point where literally everyone could afford and make photos.

In the 1930s, Universal had success with their AF series of cheap plastic cameras, and then right before the war, the so called “Chicago Cluster” exploded on the market with a dizzying array of cheap Bakelite cameras aimed at the extreme low end of the market. Regardless of which camera you bought, almost all of them shared the same basic shape and feature set. There was almost always a single shutter speed, with maybe one or two aperture settings, a single or double meniscus lens, and fixed focus.

When I first saw a Zenith Comet, I immediately dismissed it as another of these really cheap and uninteresting cameras, but then while talking to my friend Adam, he mentioned how much he liked this camera because it had a full focusing lens. A full focusing lens on a cheap plastic camera? How did they manage that?

In the simplest possible way, that’s how. There’s no helix, no rotating lens element, no sliding film plane. It’s literally just a plastic tube that slides in and out of the body with some white painted marks on the barrel to indicate the distance down to 2 feet. It’s kind of like having a collapsible lens like a Leitz Elmar, except the act of collapsing the lens is how you control focus.

Another unique feature of the Comet that differentiates itself from other simple cameras is the through the body viewfinder. The camera is designed in such a way that making photos in a portrait orientation is the most comfortable way to hold it. While there’s nothing stopping you from rotating the camera 90 degrees to shoot a landscape, it feels a bit awkward to hold the camera this way while fumbling around with the shutter release on the front of the shutter.

The front of the camera is where you’ll find every setting it has. There’s the typical “Bright/Dull” selector which is your only control over the exposure by sliding a metal plate with a smaller hole over the lens in the Bright setting.

To the left of the lens are two shutter releases, one for Instant, which fires the shutter at what I would guess is somewhere between 1/25 and 1/50, and a second Time button which works like Bulb does on most cameras where the shutter remains open for as long as you hold the button in. Without any kind of locking mechanism or a provision for a cable release and that the camera lacks a tripod mount, using this camera in Time mode without shaking the camera would be prohibitively difficult. In the Comet’s manual, it suggests holding the camera on a flat surface such as a table to prevent blur. My guess is, this feature wasn’t used very often.

Finally, on the far right is a rotating knob for cocking the shutter. Unlike many cheap cameras of the era where the shutter release simultaneously cocks and releases the shutter, the Comet requires you first cock it before the shutter release works. I see this as a good thing as it eliminates the chances of accidental exposures.

Before you can use the Comet, you need to load film into it. This requires pulling back on a chrome clip that keeps tension on the side of the camera opposite of the viewfinder. The left hinged door swings open revealing the film compartment. The Comet uses 127 format roll film which travels from left to right. Each of the compartments for the supply and take up spools are quite large and easy to fit a new spool into each side. Notice the film gate is curved, which was a common way of improving edge sharpness on inexpensive cameras with meniscus lenses. The inside of the door has no film pressure plate, instead the door has the same curve as the film plane so that the door can be used to keep the film flat-ish.

Once film is loaded into the camera, advance it using the single knob on the side of the camera and look for exposure numbers through the red window. I recommend using a slower speed film in this camera, preferably no faster than ISO 50 as anything faster will not be a good match for the single shutter speed, but also that modern film is much more sensitive to light leaks through the red windows on the back of cameras like this, and using a fast film will increase your chances of light leaks appearing on your film.

Shooting with the Comet reveals two flaws in it’s design, the first is that the through the body viewfinder does a very poor job of representing the exposed image that you’ll get on film.

I found the viewfinder to be extremely cramped, almost as if this camera had a telephoto lens. I suspected that the lens covered more than I was seeing, so while shooting with it, I accepted that some things were getting cut off in the viewfinder that would likely show up on film.

In the two images below, I am standing in the exact same spot. The image on the left is what you see through the viewfinder, and the image to the right is what the camera captured while standing there.

The other issue is that due to the nature of the focusing system in which you push the entire shutter and lens combo in and out of the body, this meant that whole pressing the shutter release buttons, you had to be careful not to accidentally change the focus of your shot by pushing the shutter and lens back into the camera. Thankfully, the Comet I was shooting was rather stiff, and as long as I didn’t use a lot of force, it wasn’t an issue, but I can definitely see how this could happen to other people.

My impression of the Comet while handling it that while it is a very cheaply built camera, it’s got just enough uniqueness to separate it from the countless cheap cameras made in the 1930s and 40s. While this may be true, what kinds of images does it make?

My Results

For my one and only roll of film through the Comet, I chose my favorite 127 film, Supre-tone. This was a film that I think dates from the 1960s, and I split a large lot of about 40 rolls with my friend Adam Paul. Adam was on the fence about such a large lot of extremely old, and unproven film, so I decided to help lessen his burden by splitting the cost of the film with him. If it was a bust, we’d share in the loss, but if it was good, then we’d have a pretty good supply of 127 film.

As luck would have it, the film was not only good, but nearly perfectly preserved in it’s original wrappers. The film has only lost about half a stop of speed from it’s original ASA 50 rating, which just so happens to be perfect for single speed cameras like the Comet.

Immediately after pulling the film from my Paterson tank, I was relieved to see 8 properly exposed images. After scanning them in and being able to fully analyze them on my monitor, I can declare the Zenith Comet to be one of the most wonderfully terrible cameras I’ve ever used!

Wonderfully terrible? What does that mean? Well, from a photographic perspective, these images are technically terrible. Light leaks and uneven exposure permeated nearly every frame, and sharpness ranges from barely acceptable in the center to down right blurry near the edges.

As I had suspected while shooting the camera, the viewfinder only approximates about the center 2/3 of the exposed image. In the image of the old house above, I could barely fit the chimney and the base of the house into frame, yet the images shows quite a bit more. In the image of the wooden boat, only the very top edge of the fence was visible.

I don’t know what the focal length of this lens is, but comparing it to the Ihagee Auto-Ultrix 2850 which is another 127 camera that shoots 4cm x 6.5cm images, that camera has a 70mm lens, and considering that most cheaper cameras tend to have slightly wider lenses to maximize depth of field, my best guess for the focal length of this lens is 60mm, yet the view through the viewfinder easily looks to be 100mm or more.

Another strange anomaly of this camera is that depending on the focused distance of the lens, the overall size of your image changes! I scanned the images on my Epson flatbed scanner to include the entire width of the film so as to show this effect. It is extremely obvious in the one double exposure of the rail yard, in which I accidentally exposed a minimum focus shot over an infinity focus shot! In a weird sort of way, its a pretty cool effect, that if I was more creative, might even look artistic when done correctly.

Technically, these images are terrible, but that’s where the wonderful part begins. For many people, shooting old cameras with imperfections can be a lot of fun. The more unique of a look you get from a camera, the more interesting it becomes, and boy, does the Zenith Comet give you some interesting images. Although I burned through this first roll pretty quickly, I can see how images of the graveyard really have potential to look very cool.

It wasn’t until after the initial shock of what I saw on this first roll that I began to appreciate the Comet. On the surface, this might look like just another cheap American plastic camera, but with it’s full focus lens, unique viewfinder, and even uniquer (is that even a word) images, I am definitely a fan. With the relative rarity of good 127 film, I don’t see myself using this camera often, but for those times where getting technically perfect images from a Nikon SLR starts to feel boring, the Zenith Comet is a great alternative and one I definitely recommend to anyone who likes the unexpected.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zenith_Comet

http://quirkyguywithacamera.blogspot.com/2016/11/the-zenith-of-quirk-comet-camera.html

https://vintagecameralab.com/zenith-comet/

http://www.artdecocameras.com/cameras/zenith/comet/

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/appareil-803-Zenith%20Camera%20Corp_Comet.html

I have collected a handful of the low-end, bakelite 127 pocket cameras. I’d like to at least shoot one roll per camera just to have some example pictures before I put the camera on a shelf. The Darkroom will develop 127 — the trick is finding new 127…. I like the ad, “New! Sensational! Focusing Camera!” 🙂 Thanks Mike — stay safe!

The images remind me of daguerreotypes. Interesting effects.