This is a Minolta Super A, an interchangeable lens 35mm rangefinder made by Chiyoda Kogaku Seiko K.K. starting in 1957. The name Super A suggests it’s part of the Minolta A-series of cameras which first debuted in 1955. Unlike the other A-series cameras, the Super A is much larger and built to a very high quality standard and had a breech lock bayonet lens mount unique to this camera. The Super A was likely seen as less expensive alternative to the Leica M and Nikon rangefinders which were popular at the time.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/2 Chiyoko Super Rokkor coated 7-elements, 5cm f/1.8 Super Rokkor coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Minolta Super A Bayonet

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder w/ 50mm Projected Bright Lines, 35mm Whole Frame

Shutter: Seikosha MX Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/400 seconds

Exposure Meter: None, Optional Clip-On Coupled Selenium Meter

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and M and X Flash Sync, if hotshoe, flash sync speed

Weight: 802 grams (w/ lens), 621 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_super_a.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Minolta Super A was a short lived interchangeable lens rangefinder camera that was aimed at the lower end of the professional rangefinder market. The build quality, ergonomics, and selection of lenses available for the camera are excellent and compared favorably to the best rangefinders on the market, however a leaf shutter with a maximum speed of 400 and a lens mount not shared by any other system hurt it’s sales. If you can live within these two limitations, this is one of the best rangefinder bargains, a camera that is built just as well and shoots the same quality images of cameras costing far more. The Minolta Super A is a hidden gem and one of my all time favorite cameras. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for overall excellence, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

History

The Japanese camera industry has a had a long history of mimicking and copying the German camera industry. Since the early 20th century, the bulk of Japanese optics were either imported or copied from German designs.

This all changed when the first World War broke out in Europe. Japan was no longer able to get things from Europe and were forced to rely on their own ingenuity and optical knowledge. As a result, in 1917, the three most prominent Japanese companies, Iwaki Glass Seizo-sho, Tokyo Keiki Seisaku-sho, and Fuji Lens Seizo-sho all merged together to form a single national Japanese optics company, which would be called Nippon Kogaku Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha, or Japan Optical Industries Co., Ltd. in English.

Nippon Kogaku’s primary goal was to produce optical equipment for the Japanese Imperial Navy such as submarine scopes, binoculars, and other equipment. Little, if any, of Nippon Kogaku’s early production ever made it into the hands on non-military personnel.

As a result, in the 1920s and 30s, a variety of smaller optics companies would be formed to produce cameras and other commercial goods. Like Nippon Kogaku, a lot of those early Japanese cameras were heavily based off existing German designs. Seiki Kogaku (later Canon) would create a copy of the Leica II rangefinder called the Hansa Kwannon which upon it’s release, would be known as the first Canon camera. Other companies like G.K. Konishiroku Honten (later Konica) would make the Pearlette in 1925 which was a near copy of the Contessa-Nettel Piccolette, and Okada Kōgaku Seiki (later Daiichi and Zenobia) made a 3×4 folding camera based loosely on the Foth Derby (the maker of this camera is actually disputed as there is no real evidence saying who made it).

Another one of these companies, called Nichidoku Shashinki Shōten was formed in 1928 by a man named Kazuo Tashima who enlisted the help of two former German camera technicians to build German inspired Japanese cameras that had equal parts German DNA but with a unique Japanese design. Nichidoku didn’t want to simply copy German cameras, they wanted to make their own.

Nichidoku would change it’s name in 1931 to Molta Gōshi-gaisha and the new company would build models inspired by other German cameras like the Plaubel Makina and the Zeiss-Ikon Ikonta and Icarette folding cameras. Several of Molta’s earlier models adopted the name “Minolta” which was believed to be an acronym for “Mechanismus, INstrumente, Optik und Linsen von TAshima”, or “Mechanism, INstruments, Optics and Lenses by TAshima” in English.

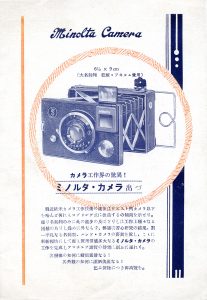

In 1936, Molta would announce a prototype for a new twin lens reflex camera that they were working on which was heavily inspired by the Rolleicord TLR made by Franke & Heidecke of Braunschweig, Germany. It featured a knob wind film advance, a German inspired shutter, and an f/3.5 lens. Before it’s release, Molta would reorganize once again and become Chiyoda Kōgaku Seikō K.K. which translates to Chiyoda Optics and Precision Industry Co., Ltd. In late 1937, advertisements in Japanese photo magazines started to appear showing Chiyoda’s new TLR, called the Minoltaflex. These early images show the camera with Compur shutters and a unique Minoltaflex logo that never appeared on production cameras.

The Minoltaflex likely went on sale in the summer of 1938 with a price of ¥245 and came with 4-element Rokkor lenses and Konan Rapid shutters which were clones of the German Compur shutter. It continued to appear in Japanese publications until September 1943, at which time it was believed that production was halted due to the war. In 1941, a second Minoltaflex called the Minolta Automat which shared the same body, front lens standard and viewfinder, but upgraded the original model with a lever wind film advance, and an automatic frame counter, bringing it’s specifications much closer to that of the German Rolleiflex Automat of the same era. Although both the Minoltaflex and Minolta Automat models were heavily inspired by their German counterparts, like most of Chiyoda’s products, they were not identical copies and had many different cosmetic and functional differences.

As with every other Japanese optical company, camera production was disrupted as a result of World War II and Chiyoda Kogaku’s factories transitioned to producing optical goods for the Japanese military. During the war, several of Chiyoda’s factories were destroyed by US bombers, so camera production took a while to start back up after the war had ended. Initially, TLRs were not included in the company’s first post-war production, instead focusing on the company’s simpler folding cameras.

One of their early post-war successes was the Minolta-35, a 35mm rangefinder based off the Leitz Leica III.. The Minolta-35 was produced starting in 1947 and shared many of the Leica’s attributes, including its 39mm screw lens mount. The Minolta-35 was a high end and expensive camera that was well built, but did little to allow Chiyoda Kogaku to stand out in the market.

By the mid 1950s, the company expanded it’s product offerings to less expensive “consumer oriented” 35mm rangefinders. This new line of cameras would be called the Minolta A-series, named after the first model, the Minolta A from 1955.

Chiyoda Kogaku would continue to manufacture and sell their Twin Lens Reflex cameras (now called Autocord), the Leica Thread Mount Minolta 35, and their consumer range of A-series rangefinders, but they weren’t done with new models.

Although I have no evidence of this, it appears to me that Chiyoda Kogaku was undecided in how to proceed with future 35mm models. They continued to evolve the Minolta 35 all the way through 1958 and continued to release new models in the A-series including the A-2, Auto-Wide, and eventually the A3, but there was also a curious camera called the Minolta A-2 LT, which was a normal A-2 but with a proprietary interchangeable lens mount. The A-2 LT was produced in very limited quantities and is very rare today, but suggests that Minolta was eyeing an interchangeable lens camera beyond the screw mount Minolta 35.

Around this same time, work began on a possible replacement to the Minolta 35, code named the SKY. SKY was an acronym for Shashin Kikai Yarikake which loosely translates to “prototype camera”.

Had it been built, the Minolta SKY would have been an very ambitious camera that would have taken on the Leica M3 head on. Featuring an all new body with a unique bayonet lens mount (not the same as the Leica M-mount), focal plane shutter with speeds from 1 – 1000 on a single dial, the ability to use the self timer for extended shutter speeds from 2 – 15 seconds, a viewfinder with automatic adjusting frame lines and automatic parallax correction, FP and X flash synchronization, and a unique rewind handle that folds into the top plate (like the Canon VT). It is said that as many as 10 lenses were planned covering all standard rangefinder focal lengths.

The images in the gallery below come from an unnamed Japanese magazine and are the highest quality images I’ve seen anywhere of the Minolta SKY prototype.

It is commonly stated on the Internet that 100 prototypes were built, but there’s a good chance this is not true. The actual number could be as low as one or two, as the only images of a SKY prototype all have the same exact serial number of 100001 which is said to be in a Minolta museum. No other prototypes have ever shown up for sale, or in private collections, which seems unlikely if there really were 100 of them out there.

Chiyoda Kogaku would never produce the Minolta SKY, likely due to a combination of how expensive it would have been, but by 1958 when it likely would have gone into production, the company was on the verge of releasing it’s Minolta SR-2 SLR camera, and the photographic world was increasingly favoring SLRs over rangefinder cameras.

Perhaps as a consolation, Chiyoda Kogaku would release a camera they called the Minolta Super A, whose name suggests it was part of their A-series lineup, but offered quite a number of improvements over the Minolta A-2 LT.

The Super A would have a unique body, not seen on any prior A-series camera that was both wider, and had it’s own rangefinder system. It would share the same (or very similar) backwards mounted Seikosha leaf shutter with a black shutter speed dial prominently located in the top plate of the camera. The lens mount of the Super A would be a unique semi breech lock bayonet type design with a selection of 6 lenses.

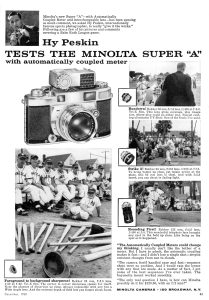

Despite being not as feature packed as the Minolta SKY, the Super A was quite a capable camera that came with Chiyoda’s best lenses. It sold in March 1958 with Rokkor 50mm f/2 lens for $129.50, or with the Rokkor 50mm f/1.8 lens for $149.50, which when adjusted for inflation, is comparable to $1150 and $1330 today.

In my research for this article, I found surprisingly little about the Super A. I couldn’t find any period reviews of the camera in any major publications, no stated estimations for how many were made or for how long. I hesitate to suggest that this had anything to do with the camera itself, rather more as a sign of the public’s waning interest in higher end rangefinders. With the exception of the Canon 7 rangefinder, no other Japanese camera maker would release an all new professional level rangefinder camera after 1960s. The only models still trickling out the doors were either scaled down versions of previous models, or low to mid-range cameras aimed at amateurs not willing to fork over big bucks for an SLR.

Today, the Minolta Super A is a fairly collectible camera. It’s rarity, quality, and unique design make it desirable with collectors and shooters alike. Although accessory lenses are uncommon, both the f/1.8 and f/2 50mm Rokkor lenses are excellent, making for a very attractive camera. It is difficult to find a camera in working condition for under $100. If you want to pick up one in great shape, expect to pay quite a bit more than that.

Repairs

This Minolta Super A came to me in good working condition with the only issue being that the rangefinder was off. Normally, rangefinders have some type of hidden screw somewhere on the top plate that allows access to a horizontal adjustment. Sometimes they’re under the accessory shoe, sometimes they’re behind another screw hole or access port on the top or even front of the camera, but with the Super A, I couldn’t find such an access port and I feared I’d have to open the camera, until I thought to remove the little black plastic panel that surrounds the rear eye piece and voila!

Rangefinder adjustment screws! These two screws are needed to correctly adjust the horizontal and vertical, but strangely, one isn’t just vertical and the other horizontal. Turning one screw adjusts the rangefinder patch diagonally, and you have to make a corresponding move with the other screw to return the rangefinder patch to the correct plane.

I wish I had simple instructions on how I was able to accomplish this, but it really was just a matter of trial and error. I set the camera to infinity and pointed the camera toward a street light a block down from my house and kept adjusting the two screws until everything lined up at infinity. It took several tries to get it right, but it worked, so if you have the same problem, just be patient and keep turning the two screws until everything is lined up at infinity. When infinity is correct, every other distance should be as well.

Since I was working on the camera, I decided to see if I could clean up the viewfinder a bit. While it wasn’t filthy, there was a fine layer of haze in the viewfinder, so I took the top plate off and cleaned everything. I won’t type a step by step tutorial on this as it was basically a matter of removing every visible screw and a small C-clip beneath the exposure counter, but everything came off neatly. Here is an image of what the Super A looks like with the top plate off for anyone who wants to attempt this themselves.

My Thoughts

From the moment I picked up the Minolta Super A, I knew this was a special camera. I loved it’s looks, it’s ergonomics, and it’s performance. This isn’t completely unusual for me, as I tend to like lots of different cameras, but the Super A was different. Each time I picked up the camera for it’s next shot, I found myself becoming more and more of a fanboy.

After finishing that first roll, I quickly loaded in another, and another, and kept shooting. By the time I thought I was ready for a review, I started to question my ability to be objective and type anything meaningful that wasn’t non stop over the top adulation.

For this review, I decided to try something different and rather than expose you to all the ways in which I like this camera, I partnered with fellow collector and photographer Anthony Rue to get his take on it. Maybe Anthony will be able to better put into words his thoughts on this camera…

Anthony’s Thoughts

The Minolta Super A has the feeling of a last ditch effort of a lost cause. 1957 must have been a difficult time for executives at the major camera manufacturers. The golden age of interchangeable lens rangefinders was coming to a close, and Leica had won the battle at the professional level with their M-mount bodies. Single lens reflex designs and aperture priority were poised to take over the professional lines, while automated fixed-lens rangefinders were primed to dominate the consumer market. To a contemporary shooter, the Super A feels like it splits the difference between the two markets.

At first glance, the Super A takes obvious design cues from the Leica M3. The Super A is a few millimeters taller, and from the top deck down it has a pleasing curved profile that fits naturally in your hand during use. While taller and thicker, the camera is slightly narrower than an M3. It has a rangefinder focusing baseline that is a centimeter wider than the Leica, allowing for easier focus at close distances. The glass bubble over the frame counter and the shape and feel of the advance lever will also be familiar to anyone who has used an M3.

If the knurled speed selection wheel seems out of place, keep in mind that it was designed to couple with an accessory shoe-mounted selenium light meter that provided recommended aperture readings. With few accurate, functioning copies of the Super A meter available, the camera will almost always be used with the speed selection wheel exposed in the dead center of the top deck. It is the one design design that makes the camera somewhat awkward to use today.

If the external design borrows from Leica, the camera itself seems to anticipate the coming generation of consumer-focused rangefinders with its build quality and construction. The 1957 M3, with a base Summarit 50mm lens, weighs a full quarter pound more than the Super A with the Super Rokkor 50mm f1.8 lens. In use, the Super A feels like a camera that compromises between the precision of a Leica or a Contax IIa and the manufacturing cost savings of a Minolta Hi-Matic, Yashica Electro 35, or a Canon Canonet. All of this makes sense when seen in context of how the Super A was marketed as an affordable-but-quality rangefinder for the emerging enthusiast market.

Sixty two years after its debut, the Super A is still a desirable rangefinder. In use, it is closer in feel to a Leica, Contax, or Voigtländer than to the fixed lens rangefinders that were to follow a few years later. Because of it’s relative obscurity among contemporary collectors and film shooters, it is possible to find a clean, working Super A for a fraction of the price of its more recognized competitors— to a point. Minolta and Leica were still twenty years away from a platform sharing agreement, and Minolta went it alone for the Super A’s mount design.

Changing lenses is easy, but only after you know how to do it it. The Super A’s lens mount is often referred to as a bayonet design, but it’s much more like Canon’s R/FL/FD breech lock mount. Each lens has a collar nearest the mount that is locked into position via a button in the center of the focus arm. To remove the lens, press this button on the focus arm while simultaneously rotating the collar counter clockwise. When a red dot on the collar lines up with a notch above the infinity position of the focus ring, the lens comes off.

Reinstalling the lens simply requires lining up 2 red dots on the lens with the notch in front of the infinity symbol, and holding the lens in position while rotating the collar clockwise until it won’t go any farther and then back it off ever so slightly until you hear the locking button in the focus arm release. This likely sounds complicated in text, but I assure you, once you’ve done it once or twice, it’s not hard at all.

Although marketed as a system with seven available Super Rokkor lenses, the Super A’s propriety lens mount design was never incorporated into any other camera system. The lenses are not adaptable to the earlier Minolta 35 cameras, nor to subsequent Minolta rangefinder models. What does this all mean to the contemporary shooter? While it is somewhat easy to find an affordable Super A with the kit 50mm f/2 or the upgraded f/1.8 lens, the rest of the lens range are quite rare and tend to be extremely pricey. The majority of wide and telephoto lenses for the Super A don’t even appear on eBay as completed sales. Your best bet of finding any of the non-standard lenses will be as part of a kit with the camera, if you are lucky. For most of us shooting the Super A, we will be limited to the 50mm. Luckily, the Super Rokkor primes are fantastic glass. I prefer the f/1.8 Super Rokkor to the 1957 Summarit 50mm f/1.5, and find that it is on level with the 1950s Zeiss Sonnar 50mm f/1.5.

Edit from Mike: I did not have access to the f/1.8 Super Rokkor like Anthony, merely having the lowly f/2 Super Rokkor, but it’s worth noting that the f/2 is a 7-element Sonnar design, as opposed to the 6-element f/1.8. Both are spectacular lenses, and I would be shocked if there is enough noticeable difference between the two to acquire both.

My own Super A came as part of a “three cameras for $40” Facebook Marketplace deal, along with a Polaroid folder and an Aries Viscount. The Super A had belonged to an American Army general stationed in Germany, and he had selected the Super A while in Japan to document his travels in post-war Asia and Europe. The camera had obviously been treasured and well cared for, with lovely touches like “Remember the lens cap” and “Slide Film” printed on the back of the camera case.

Other than a chipped edge on the take-up reel (apparently a common Super A problem), the camera was in like-new condition. Judging from the corner of the Kodachrome box flap tucked into the case, it had been decades since last use. I loaded the camera up with a roll of Kosmo Foto Mono 100 and went for a walk down Matanzas Inlet, on Florida’s Atlantic coast. A light fog had rolled in from the ocean, and the light could not have been more diffuse. Even under difficult conditions, the Super A/Super Rokkor was a pleasure to shoot. Even with the soft light and the haze from the fog, the images pop with contrast and tonal dynamics. Fine details in the landscape are crisp and distinct.

Loading the film is uneventful and familiar to anyone who has used a camera from the early 1960s with left to right film transport, a double-sprocketed roller, and a separate fixed take-up reel. The film pressure plate has 4 rounded humps which mate with corresponding recesses in the film gate to positively lock the pressure plate into position with film in the camera.

The viewfinder is large and bright with 50mm frame lines that are exceptionally bright, thanks to the large frosted window that wraps along the left side of the viewfinder. The viewfinder works edge-to-edge with the 35mm lens. External viewfinders were available for the telephoto lenses. The pale violet rangefinder focusing patch is large enough to be easy to use with glasses. Mine is a bit diffuse and would probably improve with a cleaning.

Edit from Mike: I’ve read some info on the Internet suggesting the Super A offers automatic parallax correction, but between Anthony’s camera, mine, and a parts camera I have, none seem to exhibit any form of parallax correction. Even the Super A’s manual does not mention the feature, so I can only conclude that the Internet is wrong (GASP!)

Next, I shot Fuji Color 200 at various locations across Florida. Once again, Florida weather conspired to give me overcast skies and cool tones. The colors are soft, but there is a pleasing depth to the tonal range.

For me, the camera and lens really came alive with a roll of expired ORWOpan 100. The ORWO produces results that are very similar to ADOX Silvermax, with a massive dynamic range that suits the Super A. Shooting around Silver Springs and the Silver River, the Super A delivers a fantastic level of detail and contrast, with edge-to-edge sharpness at f/2.

Finally, in homage to the previous owner’s insistence that the camera only be used for slide film, I shot a roll of Fuji Velvia 50 that had expired in 2007. In spite of the slight color shifts from the expired film, the images pop. The yellow wildflowers were shot at f1.8/400, showing a subtle and smooth bokeh free from soap bubbles or commas.

The Minolta Super A is a bit of a sleeper. It isn’t faint praise to say that it gets out of the way while you are shooting. There are no superfluous controls, nothing fussy about the layout that would distract you from shooting. It is the antithesis of over-engineered cameras that would have been contemporary, like the Voigtländer Vitessa, which requires your full attention to set up every shot. If the Super A has a down side, it would be the limited range of shutter speeds afforded by it’s Seikosha-MX shutter. With hand-holdable speed choices of 50/100/200/400, you need to carefully select your film to match your conditions. As previously mentioned, the center-mounted speed dial is the only detail that seems awkward. Mounted directly in front of the accessory shoe and with numbers canted away the shooter, you have to lower the camera and tilt it up to be able to read the shutter speeds.

It is a shame that the Super A was a failed experiment for Minolta, disappearing after only two years. Who know what we would have seen if the series had progressed— but as I have heard from several sources, by the time of the Super A Minolta had already shifted its priorities towards development of its SLR line.

If I hadn’t made it clear enough, I really enjoy shooting this camera. It is the only Minolta rangefinder that I have kept, and I’m as likely to pick it up for a day out in the swamps as any other 35mm rangefinder that I own. As much as I treasure being able to own both a Leica M3 and a Contax IIa, with each of those cameras I am consciously aware of their costs, including the required services to keep them running. I’m just not going to wander into the back alleys of Bogota or Manila with my Leica, nor go knee deep in a swamp with my Contax. The Super A delivers almost all of the quality with none of the self-consciousness at a fraction of the price. In its simplicity of design, it reminds me of a rally-prepped BMW 2002, ready for Baja. Stripped down and reliable suites my shooting style, which is why the Super A appeals to me.

My Results

For my first roll through the Minolta Super A, I chose a fresh roll of Kodak Color Plus 200. This film is a rather basic 200 speed color film that has been available in overseas markets for quite some time, but has only recently been accessible in the US, so I wanted to try it. I am very familiar with Fuji 200 and have previous shot Kodak Gold 200, so I wanted to see how the new Color Plus 200 compares to my other “go to film”.

This next gallery consists of all of Anthony Rue’s shots on the various film emulsions he mentions in his section above. I purposely put his gallery after mine as he’s clearly a better photographer than I, so I thought I would lead in with my pics before showing what a real photographer can do!

I can pretty much echo Anthony’s thoughts and say that I really like this camera and enjoy shooting it. Things like the ergonomics and viewfinder are often “make or break” things for me and with the Super A, the controls are so natural and the viewfinder is so large and bright, not getting great images from the camera is harder than getting good images.

The Minolta Super A was never intended to replace high end professional cameras like the Leica M3, but considering it’s substantially lower cost, I feel more comfortable taking this camera out on a family vacation where it might get set down on a picnic table or get jostled around in a hand bag.

If I had one complaint, it’s that I wish the shutter had a higher top speed than 1/400, but sticking to film with speeds of 25 – 100 and shooting outdoors, you can still open up the lens to get some narrower depth of field. Had the Super A been exactly the same, but came with a focal plane shutter capable of 1/1000, this might have been the most perfect camera ever.

My camera has the 7-element Super Rokkor 5cm f/2 lens and Anthony’s has the 6-element Super Rokkor 5cm f/1.8 which was offered as a $20 upgrade back when this camera was new. The f/2 lens is so good that I don’t know that if I was in the market for one of these when new I would have paid the extra money, just to get an extra third stop of exposure. I can easily declare that the Super Rokkor f/2 is up there with the best f/2 rangefinder lenses like the Zeiss Sonnar, Voigtländer Ultron, and AGFA Solagon.

Like Anthony, I wish the accessory lenses were more easily available as I would love shooting this thing with the wide angle 35mm lens, but they are so hard to find, that the likelihood of one ever coming my way at a price I can afford is very slim.

Still, the Minolta Super A has proven to be one of my all time favorite rangefinders and one I know I will keep coming back to time and time again, and based on Anthony’s comments, I am not alone in my feelings.

If you have an opportunity to pick up a clean working example of a Minolta Super A, I absolutely recommend it. This is a camera that is worth far more than the prices they typically go for today. Buy one!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_Super_A

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/minolta-super-a.481879/

http://corsopolaris.net/supercameras/MinoltaSuperA/MinoltaSuperA.html

https://wkoopmans.ca/notebook/?p=1631

https://thegashaus.com/2018/09/09/minolta-super-a/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/camerabear/galleries/72157622938688477/

Mikey, ol’ pal, reading your posts gives more cases of GAS than I care to mention!

While I’m no stranger to evoking GAS for others, I can wholeheartedly say, that this Super A is absolutely worth the GAS attack. This camera needs to be in your collection, Roger!

Well, now it is. Found one on That Auction Site with the f2 plus the original coupled lightmeter, for sale at a fair price by Westborn Camera. I’ve dealt with them before and they are honest.

I’ve bought from Westborn before too. Their prices aren’t the cheapest, but you know you’re dealing with a quality seller and they stand behind everything they sell. I am confident you will be very happy with this camera!

Hi Mike, nice review; have a look around here if you want to read more about the Minolta Super A: http://alookback.net/home/yearly/1958-2/

Mike,

A superb job again on the review of this late 50’s sleeper. I fell in love with this camera system about ten yrs ago and basically have acquired the whole kit of lenses, meters, and 3 bodies. 35/3.5 Rokkor, 85/2.8 Rokkor, 100/3.8 Rokkor, and 135/4.5 Rokkor if memory serves me right. The hardest to find was the 100/3.8. Totally agree the most annoying feature is the 1/400 top speed as I still use a lot of 400 ISO film and it just doesn’t work in this camera, unless it’s a super cloudy day or early evening. I also have the 50/2 and 50/1.8 and really don’t find much difference although if I had to have one, I’d take the 50/1.8, just because! I believe it is the same formulation as the 50/1.8 Rokkor for LTM which is a lights out lens and much in demand these days for that series of cameras as well as being used on digital.

Keep up the good work and enjoy all that you do.

Mike,

I was recently given a Minolta Super A that has been passed down from my late Great Uncle Bob who purchased it in Japan in the late 1950’s. I don’t have any interest in holding onto it and want to find it a good home. It appears to be in good shape and has all of the above mentioned lenses/accessories and original leather camera case. Would appreciate any help determining it’s worth and finding a home with someone who will appreciate it.

Jeff, I’ll email you some information.

I originally bought this camera because I was looking for a quiet rangefinder, preferably with a leaf shutter and M sync (for flash bulbs), that had a 35mm or wider lens available. This was the only camera I could find to fit that bill. Surprisingly not cheap! But maybe that’s why.

Not a fan of the ergonomics at all. Leaving the coupled light meter attached on top makes changing shutter speeds infinitely easier though but adds weight. I was hoping the leaf shutter would help me drop my hand-holdable lowest shutter speed to 1/15s but I can’t even get 1/25s to not blur with this camera.

I do love that it has a pancake 35mm lens (3.5cm f/3.5) though. I’ll have to give it another try after seeing your sample images.

Hello! I enjoyed your review of the Minolta Super A. I Have one of these and would like to clean the view finder, it’s bit hazy and the focusing patch is very dim. My question is, how is the advance lever removed? Any help would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks!

Mario, the advance lever is held on by a screw under the film reminder disc that’s on top of the winding lever. I am sorry I don’t have any pictures to show you, but if you look real closely around the perimeter of the film reminder disc, you’ll see a very thin C-clip that you need to pull off using a very tiny 1.0mm screwdriver. Be careful when pulling the C-clip off as it has a tendency to go flying. Once you have it off, the reminder disc comes off and reveals the screws beneath it. Good luck!

Hi Mike, first time I’ve read your articles, thank you for the informative review! I accidentally bought the 3.5cm/3.5 lens not looking closely enough at the picks for an LTM version. Have you ever come across an adaptor for the lenses to attach them to Sony e or Leica LTM?

Hi Damon, I responded to you in email, but for everyone else’s benefit, no, I’ve never seen a Super A adapter. I suspect it would be difficult not only to make, but to match the narrow flange distance of that camera to any modern digital. If it’s even possible, the adapter would have to be very narrow.

Hi Mike, first time reading your website, most informative, thank you for spending the time on it! Just wondering whether you’d come across an adaptor for the Super A mount lenses? Accidentally bought a 3.5cm/f3.5, hoping to be able to attach it to a Sony e-mount camera. Guessing it’s probably not possible considering the limited info online…

Thanks for the compliments, Damon. I’ve personally never seen an adapter for the Super A mount, but you could check with this eBay seller who makes all kinds of strange lens adaptions. Even if they don’t have one listed, perhaps you could contact them to have one made.

https://www.ebay.com/str/rareadapters

How do you get 1/400 speed? I thought I had an early version – but it’s the same as the reviewed camera pictured, with only 1/200 speed ….

Laszlo, I emailed you a photo of my Super A showing the 400 speed. I have two of them and they both have a 400 speed. You just have to keep turning past the 200 setting.