This is a Super Fujica-6, a medium format folding camera made by Fuji Photo Industries in Japan starting in 1955. The Super Fujica-6 shoots 6×6 images on 120 format roll film and is an upgraded version of the original Fujica Six series that first went on sale in 1948, adding a coupled rangefinder, a contoured stainless top plate, and a better lens and shutter combination. The Super Fujica-6 is considered a premium Japanese folder, comparable in features and quality to the best German and Japanese folding cameras of the day.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 7.5cmm f/3.5 Fujinar coated 4-elements

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Combined Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Seikosha-MX Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M and X Flash Sync Port

Weight: 705 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Super Fujica-6 was one of the last, and highest featured 6×6 folding camera produced both by Fuji or by anyone in the world. These cameras are well built and easy to use, and when taken care of, usually work well today. Their compact size and relatively affordable prices make them excellent options for medium format on a budget. This camera has nearly every feature included in a camera of this style, including a coupled rangefinder, an exposure counter, and an automatic stop film advance. They’re not common and are one of the more expensive 6×6 cameras, but still a bargain compared to other 6×6 TLRs and SLRs. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.3 | ||||||

History

The name “Fuji” comes from Mount Fuji, which is the tallest mountain on the island of Japan. At a height of 3,776 meters, it is only the 35th tallest mountain in the world, but is still considered to be a source of inspiration and reverence to the Japanese people. As such, the name “Fuji” has been repeatedly used in the names of several companies, from Banks, Steel Companies, and several electronics companies.

The Fuji company that produced a number of film cameras in the middle of the 20th century dates back to 1934 when it was formed as Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd. This company was an offshoot of an earlier Japanese company called the Dai-Nippon Celluloid Company who was formed in 1919 as Japan’s premiere maker of celluloid film and other products.

Fuji’s earliest products were photographic film, but it didn’t take them long to start producing other optical products such as cameras and lenses.

In the early 1940s, Fuji would expand their operations and begin making optical products solely for the Japanese military. In my research for this article, I could find very little information about what types of products these were, but most likely they were lenses for scopes, binoculars, and other war-time products.

Eventually, Fuji would reorganize into several smaller divisions, all managed under the same corporate umbrella, but what little I could find on it was hard to follow. As best as I can tell, these separate Fuji companies would all fall into a single entity known as the Fujifilm Group.

After the war, Japan’s economy was devastated, and the United States had an interest in rebuilding it to make Japan a partner in the Pacific region. In order to get the country back on it’s feet, they needed an influx of money, so during the Allied Occupation of Japan, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP for short) began looking at what Japanese industry survived the war, and tasked them with building products that could be exported to bring in money.

Companies like Fuji, Nippon Kogaku, and Canon all had expertise with optics, so cameras became a popular product to build as there was an established appetite for them. Since this needed to be done quickly, these Japanese companies were not given the luxury of long development times to come up with all new models, so instead, most new Japanese cameras were heavily bases on existing pre-war German models.

In April 1948, Fuji would release it’s first camera, a medium format folding camera called the Fujica Six which would shoot 6cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film. Fuji likely followed the trend of combining it’s own name with a ‘-ca’ suffix from ‘camera’ to come up with Fujica, just like Leica, Konica, and Nicca had done.

The Fujica Six was a rather ordinary folding camera, built in the style of German folding cameras like the Zeiss-Ikon Nettar and the AGFA Isolette with a horizontal folding door which revealed a self erecting leaf shutter and lens. The earliest cameras came with Lotus leaf shutters with top speeds of 1/200 and an f/4.5 triplet lens. With a Japanese domestic price of ¥5,250, this converted to just under $15 in US dollars at the time, a meager price to pay, but it was a start.

The Fujica Six, like many competing Japanese models with similar specs was very successful and as the company’s experience making cameras grew, it evolved with better shutters and lenses, new features, and eventually a new body.

In November 1950, an improved model was released called the Fujica Six IIBS, which replaced the simple folding viewfinder with a rigid optical finder mounted to the top plate. The shutter was synchronized for flash, had a self-timer, the lens was a Fuji designed f/3.5 triplet. This model was heavily sold through military PX stores to US solders for use while being deployed or to be taken back home, without having to pay any import taxes or fees.

In April 1952, the Fujica Six was improved once again, this time with a significantly redesigned and curvy stainless steel top plate and viewfinder. The lens and shutter was upgraded in the months after, including a new 4-element Fujinar lens and Seikosha shutter with a top speed of 1/500. The Fujica Six was no longer a cheap knock off of a German camera, it was a premium device with it’s own look, and competitive set of features.

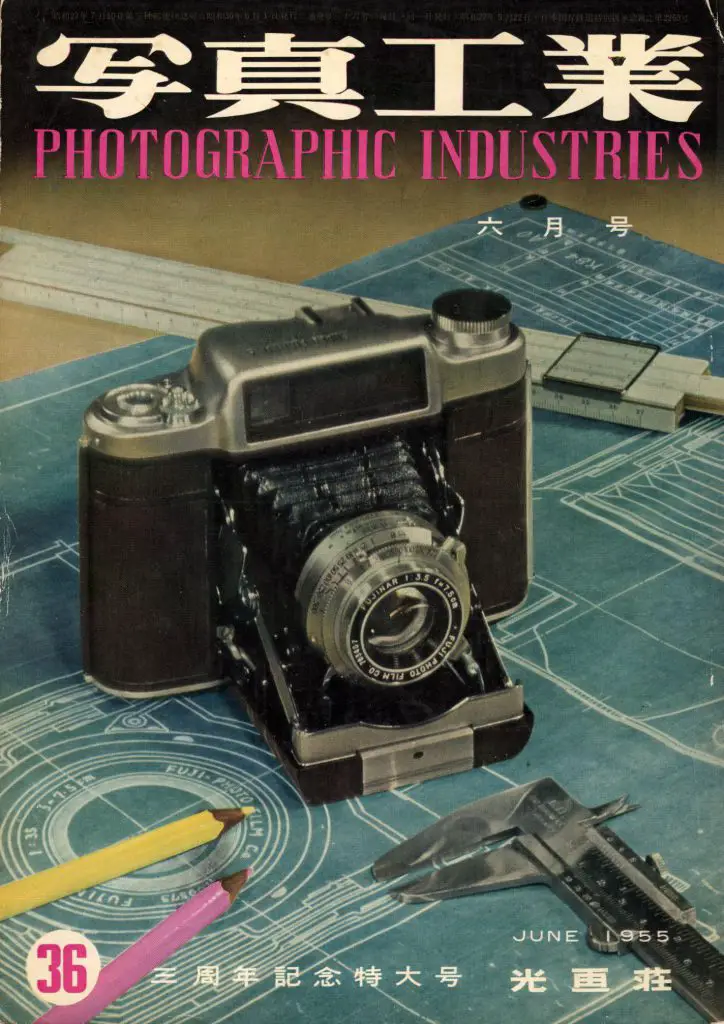

By the mid 1950s, the market for medium format folding cameras was starting to dry up, replaced by increasing interest in 35mm rangefinder and eventually SLR cameras, but Fuji was not done with the Fujica Six. Perhaps as one last effort to improve the camera to make it marketable, in June 1955 a final version of the camera called the Super Fujica-6 was released with a coupled rangefinder.

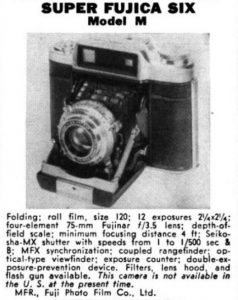

Two versions of the Super Fujica-6 exist. The one reviewed here is the second one, called the Model M, which has a different Seikosha MX shutter adding electronic flash sync, in place of the original Seikosha Rapid shutter.

The Super Fujica-6 was the pinnacle of folding 6×6 cameras. With a coupled rangefinder, a great lens and shutter, full flash synchronization, an exposure counter, automatic stop film advance, double image prevention, a self-timer, and a distinct looking body, the camera had it all. With a Japanese domestic price of ¥24,500, the price had increased by more than four times since the original Fujica Six. After adjusting for inflation, the Super Fujia-6’s price compares to ¥150,087.14 today, which when converted to US dollars is $1450.

Despite my best efforts, I could not find any advertisements or articles in US publications of the time, as the Japanese language ones above are all I found. In April 1957, Popular Photography published a Guide to Japanese Cameras, and included the short blurb to the right for the model, saying at the bottom that it was not available in the US at that time. Whether the camera could still be imported by specialty shops, or if it was later offered is anyone’s guess, but I could not find any information either way.

Eventually, Fujica would focus it’s camera making efforts exclusively into 35mm rangefinder and SLR models. Their first attempt at an SLR was the Fujicarex from 1963 and then the Fujica ST series in the 1970s. Although the company saw some success with their cameras, Fuji remained more committed to their film business primarily releasing inexpensive point and shoot cameras throughout the 80s and 90s with the occasional prestige models like the TX-1 and Klasse models.

Today, premium Japanese folding cameras like the Super Fujica-6 are quire collectable as they represent the best of the Japanese camera industry during a peak period of quality and innovation. These are cameras that were built to last a lifetime and usually with only a good cleaning and minor maintenance, cameras like these are still wonderful to shoot today and make images rivaling the best 6×6 cameras of any format, made in any country, ever. If you have an opportunity to try out or pick one of these up, even if it’s a non-rangefinder version, it is absolutely worth it.

My Thoughts

A common question in film enthusiasts groups is from people looking to get into medium format. Perhaps they’ve seen images shot with a Mamiya RB67, Hasselblad, or a Rolleiflex, but are intimidated by the different systems and the prices they often go for.

Whenever I talk to someone looking to try medium format on a budget, I often direct them to some kind of 6×6 folding camera. These cameras use the same film as found in those more expensive medium format cameras, and often have lenses and shutters capable of producing images nearly as nice, but for a fraction of the price.

There were a ton of these cameras made all over the world. American, German, Japanese, and Soviet models exist with price ranges from a few dollars to hundreds of dollars. While all of these cameras use the same basic formula of a 3 or 4-element lens mounted inside some kind of leaf shutter attached to a folding lens standard, usually with bellows, you have a huge selection of models to choose from.

If you want something more than just a basic camera, higher end models like the Super Fujica-6 added premium lenses, coupled rangefinders, auto-stop film advance, and exposure counters, making for a very capable, yet still very compact medium format camera.

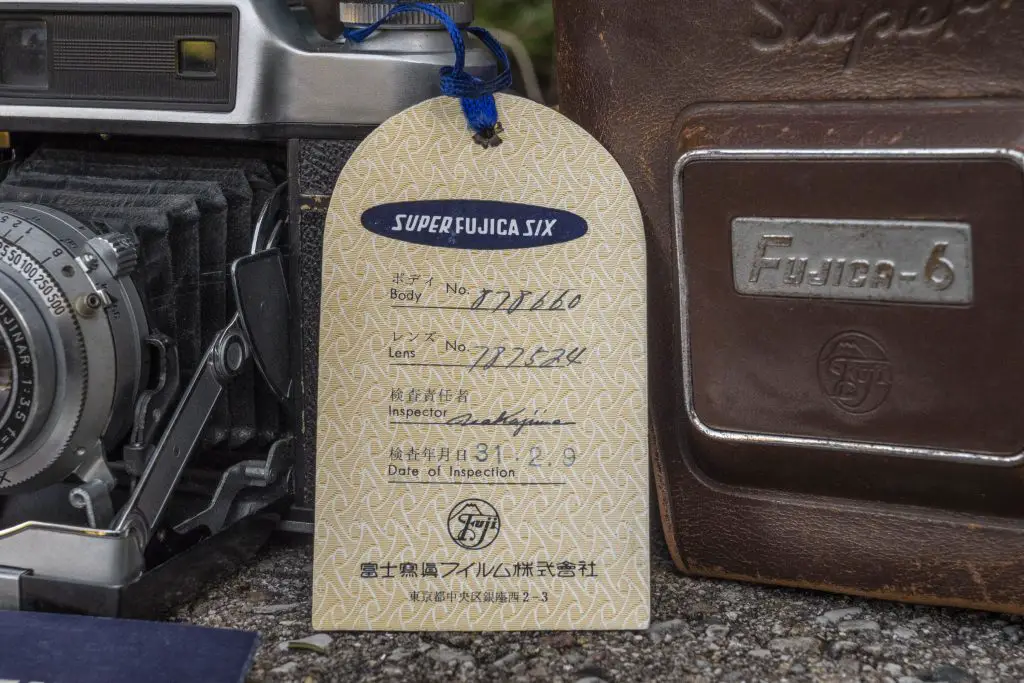

This particular camera was loaned to me by collector Kurt Ingham who included a bunch of accessories, user manual, and an almost mint condition leather case. The camera is in excellent condition, so I was eager to take it out for a test.

At a weight of 705 grams, the Super Fujica-6 is heavier than simpler 6×6 folding cameras but nowhere near as bulky as the Soviet KMZ Iskra which has a similar feature set.

The camera’s top plate has smooth curves on all sides and has the Super Fujica-6 logo etched using a very attractive “retro” typeface that somewhat reminds me of American automobiles of the 1950s and 60s.

From left to right, there is the film advance knob, which is coupled to the film transport, so turning it has a bit more tension than a simple folding camera in which the knob only spins the take up spool. On the side of the advance knob is the exposure counter. The coupling automatically locks the advance knob when the next exposure is reached. To overcome it, such as when you are at the beginning or end of a roll of film, you must press in the direction of the arrow on the small switch to the right of the knob, to the left of the accessory shoe.

On the right is a large film reminder dial with the shutter release somewhat overlapping the upper left corner. The shutter release is threaded for a shutter cable and has a round bowl around it’s perimeter to prevent from accidental presses. Below the shutter release is a small window that tells you the status of the film transport. When the window is white, it means the film has not been advanced. Advancing the film to the next exposure activates the double exposure prevention feature and turns this window red. The status of this window is not coupled to the shutter, so you must still cock the shutter manually, using a lever on the shutter.

The back of the camera is pretty bare, save for the large round eyepiece for the viewfinder, and the small window on the side of the film advance knob for the exposure counter.

Unlike many lesser 6×6 folding cameras, there is no red window for seeing the exposure numbers on the backing paper, as the Super Fujica-6 has an auto stop film advance which can detect the start of a new roll of film, without having to look for the number 1. This is a feature that on many other medium format cameras like the Kodak Medalist or the previously mentioned Iskra can jam or become defective over time, so it’s critical if you are to shoot one of these cameras that this feature works, as there is no other workaround to advance the film.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located 1/4″ tripod socket allowing for good balance when the camera is mounted to a tripod. On both sides of the bottom plate are two small round feet that are used to pull away the bottom pin for the film spools when loading and removing film from the inside of the camera.

In the image to the right, you can also see the large rectangular door release on the upper lip of the door. This not only makes opening the camera very easy, but also eliminates the need to clutter the top plate with a door release button.

Film transport through the camera is from right to left like on most folding 6×6 cameras. When loading in a new roll of film, you would normally find an empty spool on the right, which you would move over to the left and then install a fresh roll of film in it’s place.

Above and below the film gate, slightly off to the left, are two white triangles, which are used to correctly set the position of a new roll of film when loading. All types of 120 roll film have some kind of “Start” indicator which shows up on the backing paper. You must line up this start indicator on the backing paper with these white arrows in order for the camera to properly detect the start and end of each roll of film correctly.

Perhaps my favorite part of the Super Fujica-6 is in how all of the controls for the shutter, exposure, and focus are laid out on top of the shutter. Up front is the shutter speed ring which can be gripped nearly around the entire perimeter of the shutter. The shutter speed numbers can be read both from the front of the camera, but also from the top down, via a red dot on the edge of the ring.

Behind it is the cocking lever for the shutter. I actually prefer folding cameras with a manual cocking lever as those who attempt to couple this feature into the film advance often fail, or require a tremendous amount of effort while advancing film.

Next is a lever for controlling the aperture of the lens. Many medium format and 35mm folding cameras control aperture via a very small lever near the bottom of the shutter, often requiring you to maneuver your finger into a tight space, so the inclusion of this lever in an easy to reach spot is very welcome.

Finally, nearest the edge of the bellows is the focus control lever. The Super Fujica-6 uses a helical to control focus which moves the entire lens and shutter assembly backward and forward to change focus. This is more desirable than shutters with front element or unit focus as all lens elements maintain the same orientation with each other without rotating. Having the focus control here, allows you to use your left index finger to adjust the focus distance with your eye to the viewfinder while looking through the rangefinder.

The viewfinder is a simple straight through optical square with a large square rangefinder patch in the center. Sadly, I had a brain fart and forgot to take a photo through the viewfinder before sending it back to it’s owner, but if you can imagine a bright square with a square rangefinder patch in the center, you have a good idea of what it looks like.

There are no frame lines or any kind of information about the camera’s settings to be seen in the viewfinder, which was typical of similar cameras of the day. While I found the viewfinder to be easy to use, a minor nitpick I had is that as a left-eye shooter, the location of the viewfinder on the far right side of the top plate meant I had to hold the camera a bit more off center than I am used to, but I imagine right eye shooters will find it very comfortable.

One last thing I hardly ever talk about in these reviews is the case. Where most companies are content to create a generic looking leather shell in the general shape of the camera, and emboss a logo into the front, the one on the Super Fujica-6 is nicely detailed with a chrome ring around the nose and a stamped metal Fujica-6 logo in the center. The leather felt soft and thicker than most mid-century camera cases, and used reinforced clasps on the back to hold everything together.

It only takes a second after picking up the Super Fujica-6 to realize this was a special camera. Fuji clearly put a lot of thought into the camera’s design and ergonomics. The soft edges of the top plate help to minimize it’s size, the viewfinder is as good as any 6×6 folder I’ve seen, all the lens’s controls are easy to reach all in a central location above the shutter, and although heavy, the camera feels balanced in your hands. Of course a good camera is more than the sum of it’s parts. How does the Super Fujica-6 shoot?

My Results

When Kurt sent me this Super Fujica-6, it was clearly in excellent condition and seemed to be working correctly, so I quickly loaded in a fresh roll of Kodak Ektar 100 and took it with me on a fall family adventure in late 2020. When I took the first couple of shots, I couldn’t hear the shutter firing, so I took a look at it while firing the shutter and got a really nice closeup of my face as seen in the gallery below. Sometimes cameras that sit for too long just need a little bit of exercise to get going and thankfully, the rest of the roll was shot without any issues.

Wanting to give it one more go, I had a few short rolls of some Kodak 2475 Recording Film that was long expired. I believe this might have been an ASA 800 or even faster film when it was first made, but my friend Adam Paul recommended I try it out at ASA 25 and go from there.

After seeing the results from the Kodak 2475 Recording Film, Adam’s recommendation of ASA 25 seemed perfect as the images came out really nice. If you view the black and white images in the gallery above at full screen, you’ll see quite a bit of grain, but when looked at regularly, do not distract from the final image. I found the images of the cemetery and burned out house suited the gritty look of the film.

As for the Ektar, the bright blue sky and colors of the carnival rides were a perfect match for it and the camera. The Fujinar 7.5cm f/3.5 is a quality Tessar style lens that delivers very nice and sharp results corner to corner. I noticed no signs of softness, vignetting, or any other optical anomaly associated with lesser lenses.

I had the benefit of a perfectly working camera that quite possibly had recently been serviced, so everything worked, from the rangefinder to the exposure counter. For someone to invest in a camera like this, you’ll definitely want to make sure it’s in good working condition because if there are issues with the film transport, you do not have a red window in the film door to see the exposure numbers as a backup.

Normally, a big advantage to a 6×6 folding camera compared to other medium format cameras is their portability and while the Super Fujica-6 is certainly easier to carry around than a 6×6 TLR or SLR such as a Rolleiflex or Pentacon Six, it is a bit larger and heavier than other 6×6 folders. The presence of the coupled rangefinder and mechanism for the exposure counter adds some vertical height to the camera, and the overall complexity adds some weight. It’s certainly not a deal breaker, but carrying this camera for long periods of time might benefit from a neck strap which isn’t always necessary with other folding cameras.

The ergonomics of the camera are excellent. The location of the shutter release on the top plate is in a comfortable and easy to locate position. Despite the larger size of the camera. I had no trouble reaching any of the camera’s critical controls with what I consider to be medium sized hands. Winding the camera can be done with your left hand with the camera still to your eye, but generally, you’re going to lower it before shooting your next image. Lastly, all exposure controls, the cocking lever, and focus control are easily within reach from the top of the shutter. There is no need to squeeze your fingers into narrow gaps below the shutter to select a different f/stop or grip a tiny rim around the shutter to change speeds. I can’t stress enough how much of a convenience this is, as the layout of the controls is one of the most common frustration points of leaf shutter folding cameras.

My comments earlier in this article about how I like to recommend 6×6 folding cameras to people looking to get into medium format definitely apply here as the Super Fujica-6 was very enjoyable to use. The exposure counter worked great, the viewfinder was large and bright, and the Fujinar lens produced excellent images. If this camera’s images were your first experience with medium format, you would definitely be seeing a good ambassador to the format.

There were certainly other great 6×6 folders made by other companies like Voigtländer, Zeiss-Ikon, Mamiya, and KMZ, but you would be hard pressed to find one with better build quality, more features, and a better lens than the Super Fujica-6! Highly recommended!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://camerapedia.fandom.com/wiki/Super_Fujica_Six

https://www.photrio.com/forum/threads/super-fujica-6.165817/

http://www.jnoir.eu/en/cameras/fujica/super-six/

http://www.ericconstantineau.com/photo/review_superfujica6_en.html

http://www.mediajoy.com/mjc/cla_came/s_fujika/index.html (in Japanese)

https://www.kitamura.jp/photo/repairer/2012/re867.html (in Japanese)

https://kuaibao.qq.com/s/20200531A0GVKQ00 (in Chinese)

https://www.bilibili.com/video/av71654907/ (this is a video in Chinese, but shows the camera from many angles)

If this design appeals to you, also consider the Konica Pearl, models II, III and IV. These are 6×4.5 (2-1/4″ x 1-3/4″) and not 6×6, but the Hexanon lenses are superb.

In terms of the “Last Best” 120 folder, by 1958 the market for 120 folders was almost non-existent, every camera magazine was all about the latest-greatest 35mm cameras as you say. But the Konishiroku Pearl IV in 645 format was produced in December 1958 and was probably one of the very last new designs to come out. The Balda Super-Baldax was produced from 1955-58 and the Ennit 80mm f/2.8 lens was one the fastest ever released on a 120 folder. But I would have to say that the title of “Last Best” 120 folder should go to the Ensign Autorange 820 produced from 1955-58 because of it’s unit focusing method, rangefinder focusing and superb Ross Xpres 105mm f/3.8 (5 Elements in 3 Group) lens. This is a great video showing the camera … https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TFABYHZFoek

I will definitely have to check one of those out one day, but they don’t show up for sale often. Thanks for the recommendation, Cheyenne!

I like the comments regarding the Pearl IV. But that camera is rare and very expensive. I had never heard of the Super Fujica until this article. As far as carrying it around all day, I notice it doesn’t have any strap lugs (much like the smaller Mamiya Six/6 folder). Thus if you don’t have the case, you have no reasonable way of attaching a strap, am I right?

Yes, you are correct about needing the case to have a strap on it. Thankfully, mine came with the case, but I have found that if you ever want to use an original case with a strap, you should not use the original leather strap on the original leather case. The cases usually hold up well, but the leather straps themselves can often be brittle and easily broken and of course, no one wants to see a beautiful old camera falling to the ground because the strap broke! Another option, although not as elegant, is to use one of those straps that attach to the tripod socket. The camera would hang upside down from your neck, but it would work.

Mike, there is also the Peak Design Anchor Mount, although I don’t really like using the tripod socket or a camera strap: https://www.peakdesign.com/products/anchor-mount.

thanks for that nice article, I really enjoyed it. I bought one in early ’21, and since the finder needed a little cleaning, I removed the top. I was positively surprised that Fuji used a cube (prism) beamsplitter in the rangefinder, not a plate one, which is the better, but also more expensive solution: for current beamsplitters at Edmund Optics, it is $173 (10x10x10mm) vs. $43 (all sizes from 12.5×12.5 to 18x30mm) for a roughly comparable size of the reflective surface. A cube beamsplitter avoids the faint secondary reflection from the second surface of a plate beamsplitter, often visible with light sources in the rangefinder patch area. The only other folders that use beamsplitter prisms I am aware of are the Super-Ikontas A, B, and C (the later – and originally cheaper – III and VI used plate beamsplitters). The rangefinder movement of the Super-Fujica 6 is done by a sliding lens mechanism near the beamsplitter, btw.

Thanks for the comments Arne! Yes, prism beamsplitters have their own challenges. On one hand, they usually hold up better and are less likely to fall out of alignment, but if they get hazed up or are damaged, they are far harder to repair. I am amazed you even found a replacement that would work. Most Zeiss cameras of that era used prisms too. One particularly interesting camera that does is the Zeiss Contessa 35. Nikon rangefinders also use prisms too.

I definitely wish you luck in getting yours back together!

Beamsplitting cubes appear commonly available on Alibaba for only a few dollars, in roughly appropriate dimensions and qualities (I measured the OEM splitter at 12mm³, ones are commonly available in 10mm³ and 12.5³). Gonna try to shim out a 10mm one when it comes while the original sits in a solvent..

Arne, I messaged you on your site, if you see this let me know how you faired.

Very thorough article Mike, love the podcast

A well done review on a fantastic camera, Mike.

I started on a older Zeiss Ikonta 6×6. No rangefinder, an uncoated Opton Tessar with the same specs as the Fujinar shown, but a capable instrument if used properly. Upgraded to a 2×3 Crown Graphic with a Symmar 105 which could produced impressive results. Didn’t really have a digital camera that could match it until I got a Canon 5Dsr.

Few people appreciate the capabilities forsaken by the 35mm revolution.

Advancing the film cocks the shutter? I thought the shutter cocking was manual. Your review is the next best thing next to the manual. The manual is not available on line as far as I know. Thanks for the review!

On my model (The MX version) I have to manually charge the shutter. Perhaps there is a variant that charges the shutter when film is wound.

Chris, after reviewing what I wrote and playing with the camera, the way in which I described it was incorrect. Mine is like yours and the shutter must be manually cocked. I have updated the review with a corrected description. Thanks for bringing this to my attention.

I’m a bit late to the party, but really appreciated this fine review. One question I have is the filter/lens shade size. Would you kindly share that information?

Thank you.