Ever since the first cameras and first photographic processes were developed in the early 19th century, innovations have continuously come along to improve and simplify the act of making a photo. The first celluloid films in the late 1800s allowed up to 100 images to be shot without having to reload the camera, pentaprism viewfinders allowed the photographer to focus and compose through the viewfinder without any parallax error, selenium light meters allowed for cameras to help calculate exposure and later automatically expose images, and finally with the invention of automatic focus, the camera could detect the distance of objects from the lens and focus the camera automatically.

Of all the advancements in photography, one that is often overlooked was the invention of the zoom lens. This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings to you a variety of zoom lens related articles from the 20th century previewing some early releases, and also goes into the history of the earliest zoom lenses.

While I’ll never pretend to understand everything that goes into calculating the optical formulas and creating the glass needed for a good optical lens, prime lenses were perfected fairly early in the history of photography as designs like the Double Gauss and Rapid Rectilinear are still the basis for many lenses we use today.

The earliest optical lens formulas predate photography itself and were used in scopes, eyeglasses, and other optical devices. Here is a very brief and incomplete history of some notable advancements in camera lens design.

- 1812 – William Hyde Wollaston adapted an early positive meniscus lens for the camera obscura.

- 1839 – Charles Chevalier created the first achromatic meniscus lens which was a popular choice by earlier photographers like Daguerre and Niépce.

- 1840 – Joseph Petzval created the 4-element “portrait Petzval” lens, with an aperture of f/3.6 was the fastest such lens for portrait photography.

- 1866 – John Henry Dallmayer created the Rapid Rectilinear, a 4-element symmetrical lens design that greatly reduced distortion and would become the basis for a huge number of other lenses produced over the next century and a half.

- 1879 – Friedrich Otto Schott discovered ways of introducing large amounts of lithium in the creation of optical glass, that when formed into lenses, greatly improved light transmission and overall performance. His work with Ernst Abbe greatly advanced the design of all kinds of optical lenses.

Dr. Paul Rudolph is responsible for some of the most well known lenses of all time, including the Protar, Planar, Plasmat, and Tessar. Image courtesy, zeiss.com. - 1890 – While working for Carl Zeiss, Dr. Paul Rudolph created the Protar, the first true anastigmat lens which corrected spherical aberrations, coma, and astigmatism.

- 1893 – Dennis Taylor created the Cooke Triplet, a simple 3-element design that not only optimized image sharpness and speed, but was also inexpensive to make. The Cooke Triplet is one of the most copied lens formulas of all time and was the basis of many later lens formulas, many of which are still used today.

- 1902 – Still working for Zeiss, Paul Rudolph created his most well known lens, the 4-element Tessar, a formula so successful, that it has been copied by nearly every optical company. The Tessar would become the standard lens on a huge number of large, medium, and compact format cameras, including SLRs, rangefinders, point and shoot film, and even digital cameras today.

- 1935 – Alexander Smakula developed the first artificial lens coating using a vacuum deposition of a very thin layer of magnesium and calcium fluoride to suppress surface reflections.

- 1950 – Pierre Angénieux introduced the Angénieux Retrofocus Type R1 35mm f/2.5 for the Exakta, an inverted telephoto design which improved the performance and reduced the size of wide angle lenses, a design that would later be copied by nearly every lens maker thereafter.

- 1956 – Minolta produced the Rokkor 3.5cm f/3.5, the first multi-coated lens for the Minolta 35 Model II rangefinder camera.

Each of the above discoveries helped to advance the performance of lenses which have allowed photographers to capture light in a photograph for nearly two centuries. For as impressive as each advancement above was, they all share one thing in common, which is that all of them have non-moving glass elements. When a lens is built where all the glass elements always stay in the same position, the performance of that lens can be guaranteed in every situation it is used.

If you want to design a lens with a variable focal length, certain parts of the lens formula must be able to change positions within the lens. The idea of moving lens elements was explored as far back as 1834 when early patents were applied for in the UK. These early examples of varifocal lenses were crude and had a significant negative effect on the performance of the lens, as we didn’t yet have an understanding of how to correct for all known optical aberrations at multiple focal lengths.

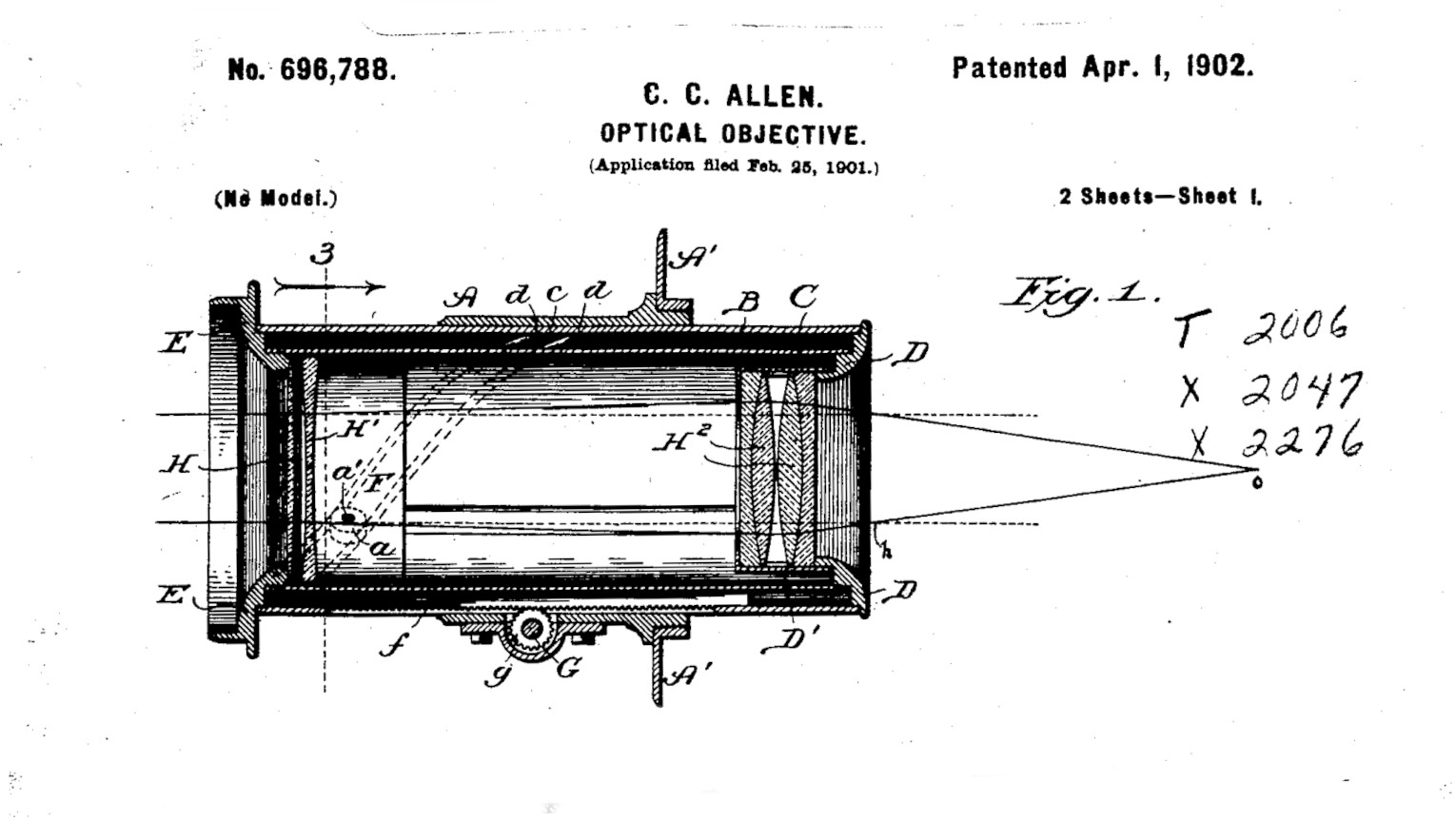

Throughout the rest of the 1800s, few advancements were made in the study of varifocal lenses. The most common references cite the next major varifocal milestone was US Patent number US696788 by someone named Clile C. Allen of Chicago, USA who in 1901 applied for a patent for an optical objective described as:

…the focal length of the lens system may be varied without the removal or substitution of some part of the lens system, and to provide further that the image formed by the objective shall remain at a fixed distance with reference to the objective for all variations of the focal length.

Other than the patent information for Allen’s lens and the same references to it on Wikipedia and a few other sites, very little is known about this early lens, whether it was actually built, and if so, who used it. It can be assumed that such a lens would have been extremely difficult and expensive to build, and anyone who successfully accomplished such a feat would have wanted to share it with others. Had a true zoom lens like this been built in 1902 when the patent was approved and delivered, it would have likely been a revelation, and it seems odd that there’s so little info about it. The fact that no one from Carl Zeiss, Voigtländer, Goerz, Bausch & Lomb, or any other prominent lens maker of the day took notice of such a revolutionary design suggests it only existed on paper and was never built.

For any concrete evidence of a zoom lens that was actually built, we have to wait a few more decades, when in the 1920s a cinematographer working for Paramount Pictures named Joseph B. Walker created a “traveling telephoto” lens which altered the focal length of a lens in a patent he filed in 1929. Although Walker would later claim to have started work on his lens in 1922, another Paramount employee named Rolla T. Flora filed another patent in 1927 for another version of a varifocal lens with moving elements.

Evidence of such a lens exists in the opening shot of the 1927 Paramount silent film, “It” starring Clara Bow. A close-up shot of a sign atop Waltham’s department store widens to show the building at a distance, then pans to the street level below and tightens again to people walking along the sidewalk in front of the building’s entrance. Noticeable vignetting is visible at the wide angle suggesting a crude lens which couldn’t cover the entire frame. Whether this is the actual first use of a zoom lens in a motion picture, or whether it used a design by either Walker or Flora is unclear, but the link both men had to Paramount Studios who produced the movie, suggests there is a connection.

Over the course of the next couple decades, varifocal lenses (they weren’t called zoom lenses yet) would remain a niche product. Their complex design likely required a huge amount of effort to build, and poor performance compared to prime lenses meant that still photographers likely had little interest in them. Because a lack of extreme sharpness is easier to hide in a moving picture as opposed to a still photograph that could be enlargened, meant that the only advancements at this time were in cinema and later television lenses such as the Bell and Howell Cooke “Varo” 40–120mm and the Rank Taylor Hobson VAROTAL III television lens.

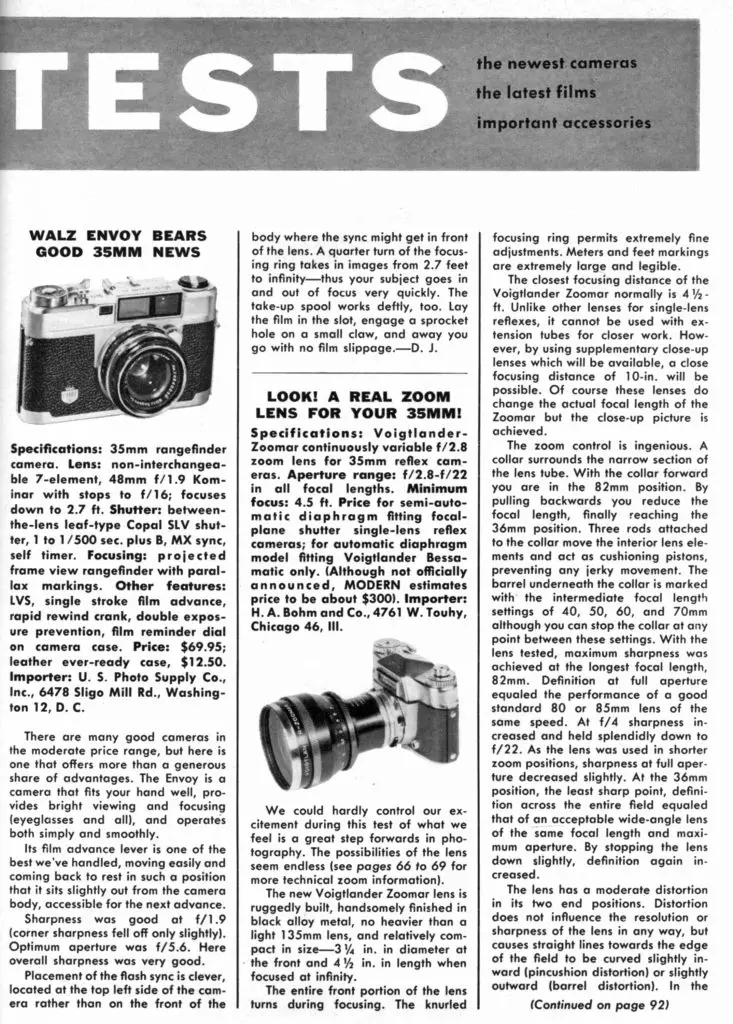

The first significant advancement of a varifocal lens for still photography was the Zoomar 36-82mm f/2.8 lens. The Zoomar was created by an Austrian engineer named Frank Gerhard Back, and is based on an earlier television lens he created around 1947.

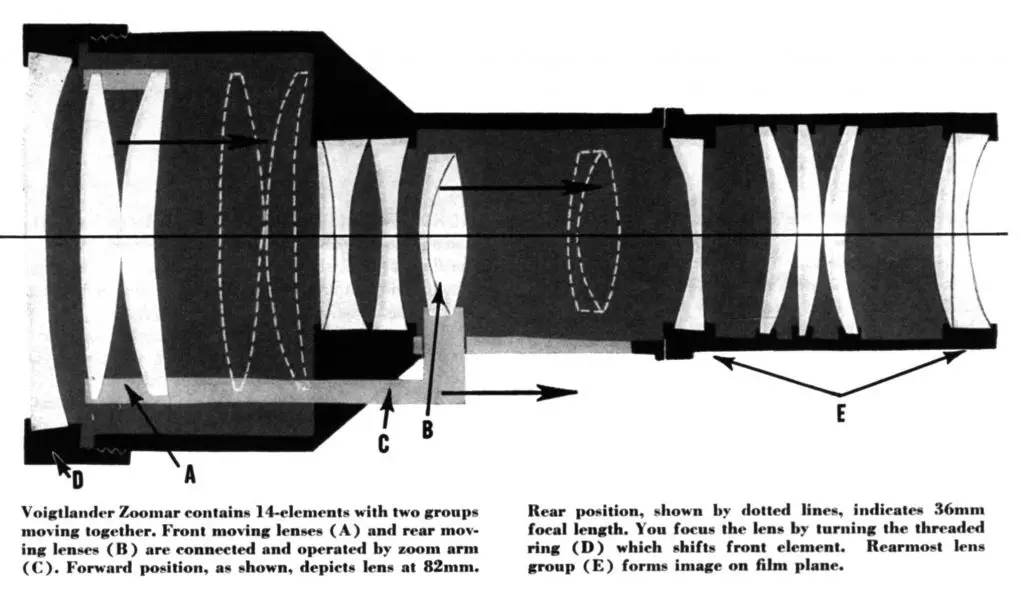

Back’s design was revolutionary, creating a system where 4 of the lens’s 14-elements and 2 of it’s 11 groups move from 36mm to 82mm. In the lens diagram below, the dotted lines indicate the final position of the “A” and “B” lens groups at 36mm.

A modest 2.3x range from 36mm to 82mm meant that the lens could retain a reasonable speed of f/2.8, good image sharpness, and that optical anomalies could be kept to a minimum, something earlier varifocal lenses couldn’t do. The use of the word ‘zoom’ likely came as a result of the Zoomar name and would be how future varifocal designs would be known by.

A version of the Zoomar would not be produced for still photography until 1959, when the German optics firm run by Heinz Kilfitt would build the lens, initially under contract with Voigtländer for their Bessamatic SLR, but would later make the lens with Pentacon (M42) and Exakta mounts. The Bessamatic’s Deckel bayonet mount is almost identical to the Deckel mount used on the Kodak Retina Reflex, so although the lens was never officially offered for Kodak’s SLR, it could easily be modified to fit on that camera as well.

A close (but not identical) copy of the Zoomar was also produced in the Soviet Union by KMZ as the Rubin-1. Although very similar to the Zoomar, and available in a similar Deckel mount to the Voigtländer Bessamatic, the Rubin-1 has a different focal range of 37-80mm, a slightly different arrangement of 14-elements, and a completely different rotating focus ring compared to the Zoomar’s “push to focus” system.

When it was released, the Bessamatic’s Zoomar was a revolutionary success. For the first time, still photographers could achieve both wide and long focal lengths without changing lenses. Although the Zoomar’s performance was not on par with dedicated prime wide and telephoto lenses, it’s flexibility more than made up for the disparity.

In the May 1959 issue of Modern Photography, both Herbert Keppler and Bennett Sherman took a long look at the Zoomar, explaining it’s design, use, and showing samples of it’s flexibility. In their test of the lens’s performance, Bennett Sherman noted that the Zoomar did a good job at controlling astigmatism, coma, and color shift throughout the entire range under 50x magnification. He closes with the declaration that the Zoomar has successfully reached a high quality in the 35mm field, and accurately predicts that more would follow it’s lead.

Later in the same issue, Herbert Keppler puts the Zoomar through a more rigorous “Modern Test” comparing it to that of the Bessamatic’s standard 50mm Color-Skopar lens and notes that the Zoomar exhibits more distortion and less contrast, but that most deficiencies could be minimized in post processing.

Although the Zoomar would open the door to future zoom lenses, there was not an immediate rush of new options as the complexity in creating new designs was still quite high. By the early 1960s, a lot of the math needed to create new optical formulas was still done by hand. Computer aided designs were still in their infancy and although some manufacturers incorporated computer technology in lens design, it wasn’t producing a windfall of new zoom lenses yet.

By 1962, a few options beyond the 36-82mm Zoomar existed. In the May 1962 issue of Popular Photography, Cora Wright would create the first “buyer’s guide” to zoom lenses, grouping models by those available in the US, abroad only, and upcoming lenses in the works.

Of the five lenses available in the US besides the Zoomar, all were telephoto zooms, ranging from Minolta’s Auto Zoom Rokkor 80-160mm f/3.5 all the way to the monster 4.6 lb Auto-Nikkor 200-600mm f/9.5. In the “abroad only” category, you have the rather ordinary preset Sun Tele Zoom 90-140mm and the French made Zoomalik 35-75mm f/2.8 with 15-elements and available only on a proprietary Malik Reflex camera or in Exakta mount. The Zoomalik was the only other lens offering a sub-50mm focal length at the time, and is said to have only been produced in 1960, never making it into widespread production.

Finally, an additional five lenses would be teased including an Argus lens in development for the Argus SLR that would never be finished, a second Zoomar, something from Schneider-Kreuznach, another Sun tele-zoom, and the Auto-Nikkor 43-86mm f/3.5 that would first be available permanently attached to the Nikon Auto 35, and a larger version available in Nikon F-mount.

The Auto-Nikkor seen in the image to the right attached to a Nikon EL2 would be the company’s first “kit zoom” lens, sold to amateurs looking for focal length flexibility, much in the way the Zoomar did, but at a lower cost. For someone willing to plunk down $199.50 for the Nikon Auto 35, or $129.50 if they already had a Nikon F or Nikkorex F (the Nikkormat wasn’t yet available), they could have the convenience of a 2x zoom.

The 1962 Pop Photo article made frequent use of the word “compromise” in it’s analysis which was something that was prevalent in discussions of all zoom lenses of the era. While the convenience of a variable focal length was undeniable, none of these lenses could deliver the same optical performance of prime lenses covering the same range. If you professionally shot portraits and needed an 85 or 105mm focal length, you would be better off getting a prime lens of that focal length, rather than a zoom who would also cover that same length, but if that was something you only thought you would do once in a great while, the convenience of a zoom might be for you.

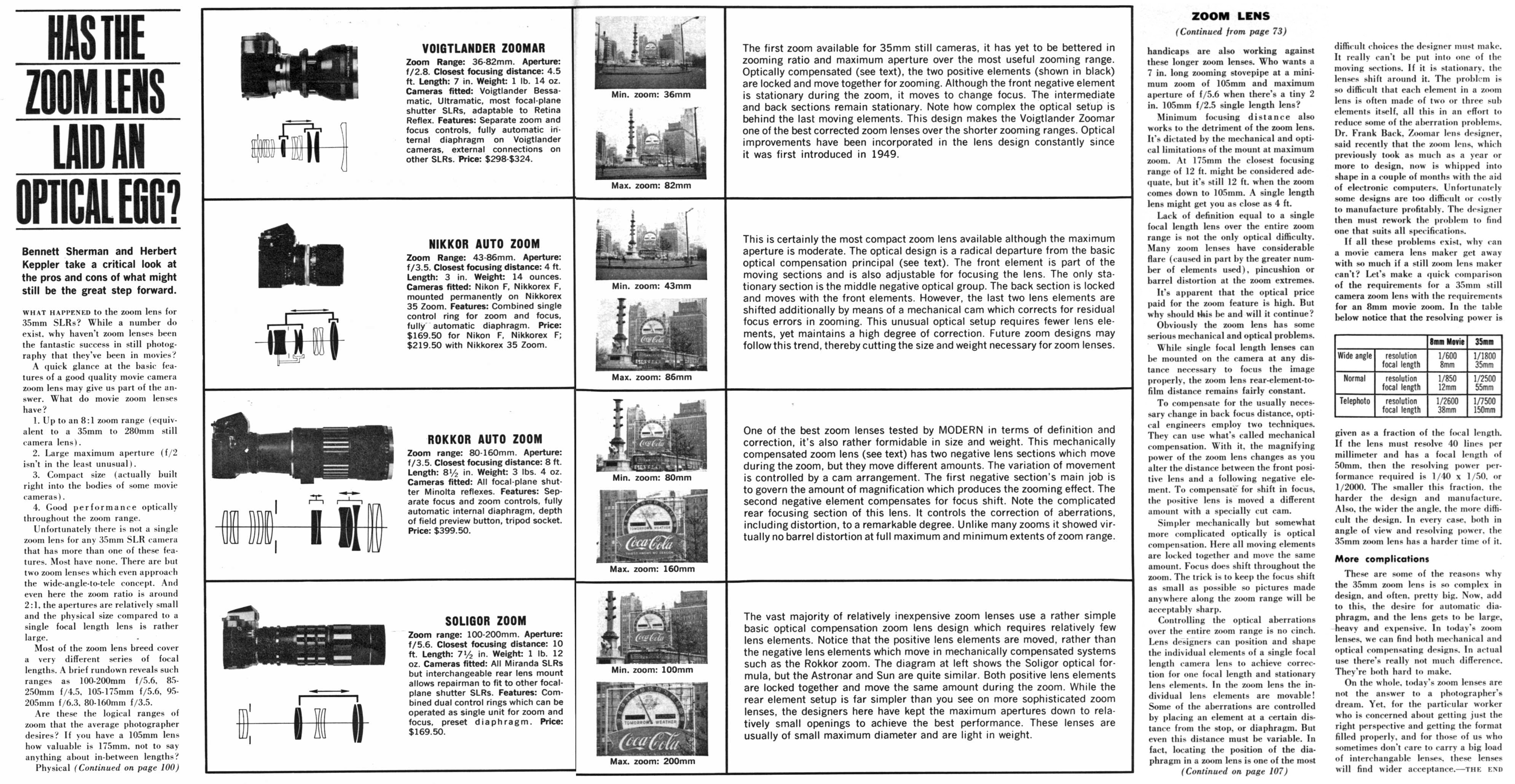

In the years to come, new zoom designs would continue to trickle out at a slow rate causing Herb Keppler and Bennett Sherman in March 1964 to ask the question, “Has the Zoom Lens Laid an Optical Egg?” Still using the original 36-82mm Zoomar as a basis for comparison, both Keppler and Sherman compared it to three additional lenses, the Auto-Nikkor 43-86mm, the Minolta Rokkor Auto Zoom 80-160mm, and the Soligor Zoom 100-200mm.

The article starts out asking why zoom lenses for still photography have not lived up to their initial hype, or why long available cinema zoom lenses outpaced their still photography counterparts with good performance, fast speeds, and wide ranges of focal lengths. It continues by criticizing less than useful focal lengths, long minimum focus distances, and that most currently available options were very large and heavy.

Perhaps the most glaring criticism was that of optical performance. While initial reviews of the Zoomar from 1959 did note that the lens had increased distortion and less contrast than prime lenses, these shortcomings were largely forgiven because the technology was new. It was assumed that future zoom lenses would quickly build upon the Zoomar and improve optical performance, something that five years later, hadn’t happened.

In his assessment of the state of the zoom lens, Keppler writes that Frank Black, the original designer of the Zoomar suggested that with modern computers, new designs can be calculated much quicker, but at a much higher cost making the lenses uneconomical to produce, requiring lens makers to simplify them for profitability sake. Although he doesn’t say it, it is not a stretch to suggest that the poor performance of mid 1960s zoom lenses was a direct result of cost cutting.

This perceived lack of quality would permeate the entire industry and zoom lenses would develop a poor reputation for quality among professional and semi pro photographers.

Zoom lenses would eventually improve, as the understanding of the math needed to build a high performance lens grew, and the cost to build them dropped, more and more quality zoom lenses would eventually hit the market.

One very notable zoom lens was the Minolta Rokkor-X 40-80mm f/2.8 Zoom from 1975, also known as the “Gearbox Zoom” as it employed a very interesting side mounted gear box that controlled the motion of the lens elements inside. Using an optical arrangement of 12-elements in 12 groups, the Minolta’s gearbox could individually control the movement of each element, meaning that no sacrifices needed to be made in optical performance at any focal length.

The gearbox Minolta proved that an optically excellent zoom lens could be created, albeit using a very complicated and unorthodox design. No other gearbox zoom lenses would ever be created, but thankfully they didn’t need to as modern computers had advanced enough that high quality zoom lenses could now be created with excellent performance and at a reasonable cost.

One such lens was the Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/3.5 from 1975. This lens, originally a 15-element design in 10 groups, was later redesigned with 14-elements in 10 groups and was extremely popular with photographers at every level of profession for it’s excellent performance, reasonable size and weight, and inexpensive price tag. First produced by Kiron and later by Tokina, Komine, and eventually Cosina, the Series 1 finally swung the door open that the Zoomar first opened to a whole world of high quality zoom lenses made both by first and third party optics companies.

For the past three decades or so, nearly every camera sold came with a standard zoom lens. Some photographers still prefer the look and operation of a prime, not to mention they usually are still a bit smaller, so there’s definitely still a reason not to use a zoom lens today, but that they can’t offer excellent results is no longer the concern it once was.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

Zoom lens, you say? I had seen/heard of zoom lenses for movie cameras, but the world off 35mm was a desert as far as “affordable zoom” was concerned in the 1960’s. My first zoom was Ye Olde 43-86mm f/3.5 Zoom Nikkor, which made my Nikkormat FTN more interesting. Back then, I had a mix of Soligor and Vivitar lenses, which is what a college student could afford.

I had used “the usual suspects” of lenses for a 35mm Nikon S2 outfit. (35mm/50mm/85mm/135mm) and judged 35mm SLR lenses against these old gems. (My father had recently gotten a Topcon RE Super and passed down the Nikon S2.) Back then, longer-than-135mm lenses for the 35mm SLR was my focus, since rangefinder cameras stopped at 135mm without a mirror box.

The 43-86mm f/2.5 Zoom Nikkor was less than impressive. Close focus was 1.2m/4 feet, which made portraits difficult and a 43mm lens that had a 1.2m fence around it was…disappointing. Pedestrian fixed focal length Soligor and Vivitar lenses “got closer” and an f/2.8 maximum aperture was a big thing in the days when ASA 400 was the “speed king.” Plus, as my Canon FT-using-classmate would point out, it was fuzzy, produced optically distorted images, and lacked contrast, compared to fixed focal length lenses.

I went back to the 90-230mm f/4.5 Soligor “long zoom” that was unsharp wide open, exhibited internal lens flare that couldn’t be cured with a lens shade, and was low in contrast. I dreamed of one day getting the 80-200mm f/4.5 Nikkor zoom, but that was years away. I did consider the Vivitar Series One lenses, but by that time, I’d bought a few Nikkor lenses. I looked at Tamron’s early “short zooms,” but came away disappointed at these Konica Autoreflex-era lenses. Tamron’s SP lens line, however, was much better, and the 90mm f/2.5 Tele Macro in Adaptall-2 lens mount let me pick up other camera bodies (Pentax, Konica, Canon, Minolta). The 35-80mm f/2.8-4 Tamron SP was a good value for these camera-body-hopping days of the 1980’s.

In the 1970’s, Canon announced a lineup of zoom lenses, which seemed a bit odd, for a major OEM camera maker,but that quickly became the norm, even for Nikon. These days, zoom lenses are the norm, while fixed focal length lenses are for Artistes.;)

We forgot the 1936 Siemens Transfokator, one of the first attempts to mass-produce variable focal length lenses for the 16mm siemens camera, like Som Berthiot’s pan Cinor, manufactured industrially from 1948 to equip 16mm and 8mm cameras. Som berthiot was the first industrialist in the world to produce zooms industrially, Moreover there is a video where inventor of the pan cinor Roger Cuvillier (1922-2019) explains his invention https://youtu.be/BTuz7GtJihc

I did not come across this lens in my research. Thank you for sharing it with us! 🙂

It’s fascinating how ground-breaking the original Zoomar was. Massive, for sure, but quite competitive with the fixed focal lengths of the day. Supposedly, one of the reasons why Voigtländer commissioned the 36-82mm lens was because the leaf shutter used on their cameras limited the maximum aperture possible on lenses, at a time when Japanese companies were having a race to see who could make the fastest, most exotic designs. In that scenario, a constant f/2.8 zoom lens was certain to draw attention, and possibly become the ‘killer app’ of the system (which in the end it wasn’t, as its performance was still compromised and the price of the lens was a typical West German affair, i.e. grievously expensive).

BTW, the photo of the Minolta gearbox zoom is from Roger Cicala, who owns a copy and apparently has quite a collection of classic photo equipment. Despite being far more known as the ‘king of gearheads’, he has a big soft spot for older cameras and lenses. Maybe you could invite him to a podcast sometime?