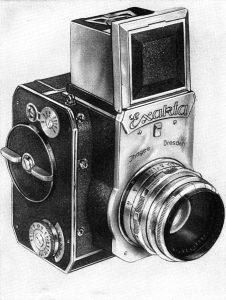

This is an Exakta 66, a medium format Single Lens Reflex camera, produced by Ihagee in Dresden, East Germany starting in 1953. This model was the second Exakta 66 produced and is referred to today as the “vertical” model as the film transports vertically through the camera, compared to an earlier version from 1939 that traveled horizontally. The Exakta 66 shares some similarities to Ihagee’s 35mm Exakta cameras, including their unique shutter speed system that uses the self-timer for slow speeds down to 12 seconds. The camera has a very attractive styling, but was plagued with reliability problems which caused the camera to earn a poor reputation when it was originally built. After production ended, it would be the last medium format camera produced by Ihagee.

This is an Exakta 66, a medium format Single Lens Reflex camera, produced by Ihagee in Dresden, East Germany starting in 1953. This model was the second Exakta 66 produced and is referred to today as the “vertical” model as the film transports vertically through the camera, compared to an earlier version from 1939 that traveled horizontally. The Exakta 66 shares some similarities to Ihagee’s 35mm Exakta cameras, including their unique shutter speed system that uses the self-timer for slow speeds down to 12 seconds. The camera has a very attractive styling, but was plagued with reliability problems which caused the camera to earn a poor reputation when it was originally built. After production ended, it would be the last medium format camera produced by Ihagee.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 80mm f/2.8 C.Z. Jena Tessar coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Lens Mount: Exakta 66 Bayonet

Focus: 3.3 feet / 1 meter to Infinity

Viewfinder: Waist Level Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: T, B, 12 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Viewfinder Blind, Shutter Lock, Battery Check Button, Double Exposure Lever, Mirror Lock Up

Weight: 1562 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/Exakta66Manual.pdf

Manual (in German): http://ihagee.org/Manuals/ECM46-Exakta66V1952.pdf

I doubt there’s many camera collectors out there who are unaware of the Ihagee Exakta. Whether it’s one of the company’s many 35mm SLRs produced from the mid 1930s through the 1970s, to some of the lesser name variants of Pentacon cameras from the 1970s and 80s, to perhaps the company’s original 127 roll film Exaktas from the 1930s. You would be forgiven however, if you didn’t already know that the company also produced 120 roll film SLRs for a while.

I’ve covered the history of Ihagee a number of times, most recently in my detailed review of the Ihagee Night Exakta B from earlier this year. Rather than repeat all of that here, I’ll summarize that, but recommend you check out the review for yourself to read the whole thing if you’re interested in learning more.

Ihagee was founded by a Dutchman named Johan Steenbergen as Industrie-und Handelsgesellschaft which stands for Industry and Trade Society. Often referred to by the nickname IHG, the company name was eventually shortened to Ihagee Kamerawerk since Ihagee is pronounced the same in German as saying “I H G”.

In 1908, at the age of 21, at the recommendation of his uncle, Steenbergen decided to focus entirely on his love for photography and moved to Dresden, Germany. There, he started an apprenticeship with Heinrich Ernemann, AC Dresden, where he worked as a mechanic. In 1910, Steenbergen was listed on a patent for Ernemann, suggesting he quickly advanced to the company in some sort of design or engineering position.

In April 1912, Steenbergen, with financial backing from the bank of Dresden, formed Industrie-und Handelsgesellschaft m.b.H. Kamerafabrik mit Kraftbetrieb as a wholesale trader of photographic products (equipment, accessories and chemicals) and the production of equipment. At this time, there were already a large number of Dresden based photographic businesses, so Ihagee’s original purpose was likely to supply those companies using parts built by someone else. Within a few years after it’s creation, Ihagee’s focus narrowed to construction of new equipment and the company’s name was shortened to Ihagee Kamerawerk

GmbH.

Little is known about the exact identities of Ihagee’s products as many were sold as “white label” designs for other manufacturers or distributors. There were some branded cameras sold under the names Photorex and Coronoa, but a large number of early Ihagee cameras were not labeled with a name, making identifying early Ihagee cameras very difficult.

Between 1919 and 1923, Ihagee’s business grew and moved locations a number of times, and in 1923, the company’s location was in the Dresdener district of Striesen, near factories for Ernemann and Ica.

Despite moderate success in this era, by the start of the 1930s, Ihagee was still a couple of years away from the company’s greatest accomplishment, the Exakta camera. It is not clear when work began on the Exakta, but interest in a miniature format single lens reflex may have begun around 1925 with the release of the Leica which used double perforated 35mm film.

The Leica was produced in Wetzlar, and despite still being a German company, might as well have been a world away. What was going on in Wetzlar had little effect on Dresden, at least not until 1932 when Zeiss-Ikon released the Contax.

Ihagee’s experience making large format reflex cameras like the Ihagee Paff-Reflex and Serien-Reflex, likely motivated them to produce a miniature reflex camera. Instead of using double perforated 35mm film like Leitz and Zeiss-Ikon used, Ihagee’s new camera would produce larger 40mm x 65mm images on 127 roll film. The term “miniature” when applied to film in this era included all types of small film, including 35mm and 127.

Whoever and however the Exakta came to be, the earliest cameras rolled off Ihagee’s assembly lines in late 1932 and the camera would make it’s debut at the 1933 Spring Fair in Leipzig, Germany. The name Exakta is thought to refer to being able to see exactly what will be captured on film through the camera’s lens.

The first Exaktas introduced a trapezoid shaped body that would remain a staple of Ihagee’s camera design for the next several decades.

Unlike the more common Exaktas from the mid 20th century, these earlier models used type 127 roll film, which was commonly known at the time as “Vest Pocket” film as it was commonly used in compact folding cameras like the Kodak Vest Pocket. Images shot in Vest Pocket Exaktas were 40mm x 65mm, larger than images from the Leica, giving them additional detail and resolution.

A variety of different models were produced of the Vest Pocket Exakta, some more basic than others. They came in black painted and chrome bodies and had a large assortment of interchangeable lenses made for them. The Exakta was warmly received as it’s compact size and larger than Leica images meant that it could produce exposures with excellent quality. With it’s interchangeable lens mount, and a long list of accessories made for it, the Exakta was the first compact single lens reflex system camera.

The Vest Pocket Exakta was a moderate success, but did not compete with Ernst Leitz’s Leica, or other German 35mm competitors like the Zeiss-Ikon Contax and Kodak Retina. As a result, in 1936 a version of the Exakta using standard 35mm film called the Kine Exakta was released. The name “Kine” is German for “cine”, short for cinema film. At the time, the most common type of 35mm film was double perforated cinema film most commonly used by the motion picture industry. The use of 35mm cinema film in still photographic cameras began to be more common in the 1910s, but really didn’t hit the mainstream until the first Leicas. As a result, many early 35mm cameras were said to use “kine” film, rather than the generic label of “35mm film” like we use today.

After the release of the Kine Exakta, Ihagee was not done expanding the Exakta brand to new film formats and got to work on a larger, medium format version of the camera. Although Vest Pocket film is technically considered medium format, it’s small size compared to other roll film formats, limited it primarily to amateur use. Unlike the Vest Pocket Exakta which was pretty advanced and was capable of excellent images, a large number of 127 roll film cameras were pretty basic, marketed towards amateur and beginner photographers.

By the mid 1930s, 6cm x 6cm was the preferred image size for the pros with twin lens reflex models like the Rolleiflex and others like the Zeiss-Ikon Ikoflex and Voigtländer Superb selling well. To capitalize on the growing preference for the 6×6 format, in 1937 Ihagee got to work on the Exakta 6×6.

In charge of the design of the Exakta 6×6 was Willy Teubner, who was one of the men responsible for the original model. This new model would share a similar body shape, shutter design, and feature set to the Kine Exakta, clearly indicating Ihagee’s desire for a similar family resemblance. Supporting larger 120 roll film, the body was larger in every dimension and required it’s own lens mount, not shared by either the Vest Pocket or Kine Exaktas. It is said that one of the earliest challenges of designing the new camera was in the film transport. Multiple sources online suggest that Ihagee designer, Karl Nüchterlein had doubts about the feasibility of using an unperforated paper backed film like 120, despite the fact that many other single and twin lens reflex cameras did it.

Prototypes of the new camera were created in 1938, but a version close to the final model would not be seen until the 1939 Leipzig Spring Fair. By that time, multiple other models of 6×6 SLRs were on the market like the Kochmann Reflex-Korelle and Beier-Flex II, all of which were simpler cameras but sold reasonably well. Continued manufacturing problems delayed the eventual release of the Exakta 66 until August of that same year.

It turns out, the film transport was a challenge, and was the primary reason for the delay in releasing the camera. Making matters worse, with war looming, German manufacturing was more and more being reallocated for other purposes. Between August and November 1939, a total of around 1500 cameras were made before production was halted.

Despite such a small number of Exakta 66s being produced, there were two notable versions of the camera. The first, which was announced at the same 1939 Leipzig fair, was a “Night Exakta 66” which, similar to the Vest Pocket Night Exaktas, would be sold with a fast f/1.9 Primoplan or f/2 Biotar lens, and perhaps some other minor revisions to the camera.

The second, only became known within the past 20 years, which were military use Exakta 6×6 cameras. These rare cameras, only two of which are known to exist, have engravings consisting of a Reichsadler (the Eagle of the Third Reich), a Swastika, and the letter M followed by a three digit number. The use of the letter “M” by itself suggests these were used by the Kriegsmarine, or the German Navy. Matching M numbers were engraved on the body, lens, and case.

While it was in production, Ihagee offered three different versions of the Exakta, the Standard, Kine, and 6×6, which was the only time in the company’s history that three distinct Exaktas were ever made.

Production of the Vest Pocket and Kine Exaktas would last a little longer than the 6×6, but by the end of 1940, all camera production at Ihagee’s Dresden plant was halted. When the war was over, the 35mm Exakta was the only model to resume production. That no other version was being made, but also that the use of the word “kine” to refer to 35mm film had fallen out of favor, the Kine Exakta was the only Exakta.

In 1950, there was enough interest in resuming production of the Exakta 6×6 that work began on production of the prewar model. Before re-releasing the camera, Willy Teubner, now Ihagee’s Technical Director, wanted to fix the issues with the prewar model’s film transport. An updated prototype for a postwar Exakta 6×6 was revealed in March 1951 at that year’s Liepzig Spring Fair which was very similar to the pre-war model. Externally, the new model had four, instead of two flash sync ports, and additional strap lugs on the side of the mirror box. The biggest change was a newly designed Carl Zeiss Tessar 8cm f/2.8 lens not found on prewar versions. A similar prototype was also shown at the 1952 Photokina, but it is not known if it was the same camera, or if there were changes.

There is inconsistent information online whether or not postwar versions of the prewar Exakta 6×6 were produced with the changes shown at in the 1951 and 1952 prototypes. According to German camera historian Richard Hummel, around 350 copies of the postwar Exakta 6×6 were produced. Exakta historian Horst Neuhaus disagrees, and on his Exakta 6×6 history page, suggests that the actual number is probably closer to two dozen. Whichever of these two estimates is accurate is anyone’s guess, but it’s safe to assume the real total is “not many”.

Exactly why a postwar version of the prewar Exakta 6×6 failed to be produced in large numbers is unknown. Theories that Ihagee was never able to resolve the film transport and other reliability problems are the most common explanation, but another is that the original camera did not offer any support for interchangeable magazine or plate film backs. It is likely Ihagee wanted to market the medium format Exakta to professional photographers who would want the ability to swap preloaded backs of film quickly in the field without reloading. A possible third reason that is my own, is simply that the original camera’s design was already dated and difficult to hold.

Development of an all new Exakta 6×6 camera was ongoing while the postwar version of the prewar camera was being shown. Instead of adapting the earlier design, the new camera would be all new. The most significant difference between the two is a change in the direction of the film transport. Unlike the earlier model, which took it’s design from the Vest Pocket and Kine Exakta’s horizontal film transport, the new model transported film vertically, similar to a Rolleiflex. It is this distinction that many collectors identify the two different Exakta 6×6 cameras, the earlier as the horizontal model, and the later the vertical since Ihagee marketed both, simply as Exakta 6×6 or Exakta 66.

The new vertical Exakta 66 (as it was called, dropping the ‘x’) made it’s debut at the 1952 Leipzig Autumn Fair. The new camera shared a similar waist level folding viewfinder and shared the same lens mount as the earlier model, but was otherwise completely different. Featuring interchangeable magazine backs, a new automatic stop film transport, a cloth focal plane shutter with 29 different speeds from 12 seconds to 1/1000, and the same standard 8cm f/2.8 lens found on the updated prewar model, the Exakta 66 was an impressive camera.

A drawing of the 1952 prototype originally appeared in the September 1953 issue of the German language magazine, Bild Und Ton to the right. An updated version of the same drawing appeared in Exakta Times No. 14 in June 1994.

The prototype version differs from the final version by showing the original smaller lens mount, the numbers ’66’ are not beneath the Exakta logo, both the shutter release lock and exposure counter reversing knobs are missing, a smaller magnifying glass loupe in the viewfinder, and has various cosmetic changes of the film advance knob and around the slow shutter speed dial.

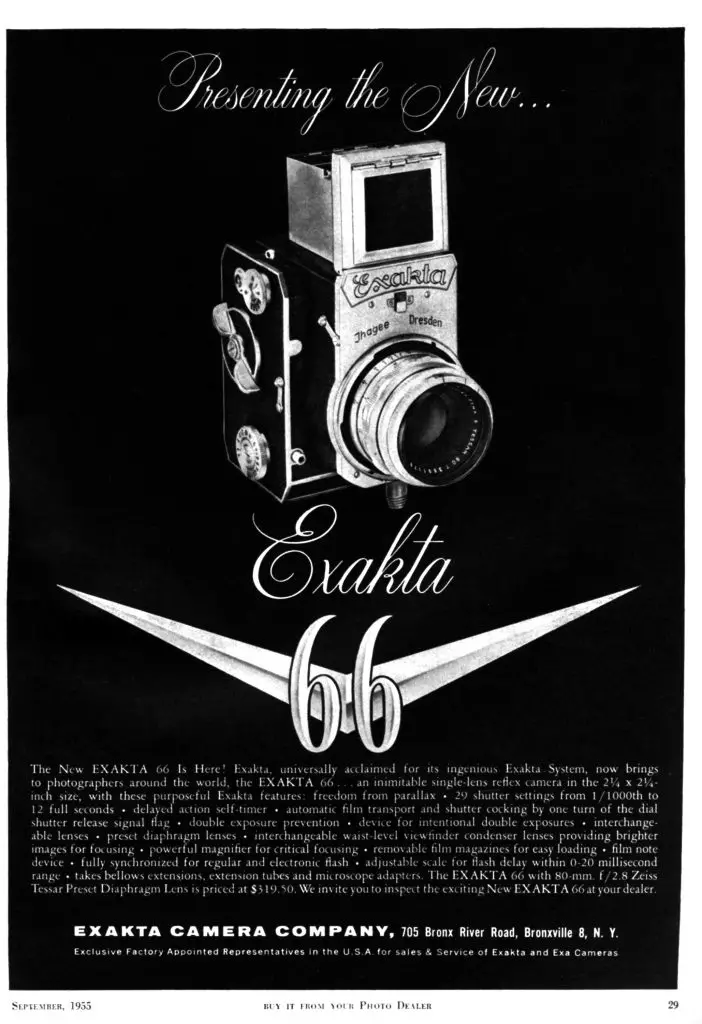

An announcement in a 1953 issue of Exakta Magazine revealed that the camera would be exported to the United States with a starting price of “around $300”. In an ad published in the September 1955 issue of Modern Photography, the actual price was $319.50 with the 80mm f/2.8 Tessar, which when adjusted for inflation compares to just over $3500 today, putting it well within the midst of other professional level cameras.

In the early 1950s, the 35mm Exakta SLR was at the peak of it’s popularity. Back then, rangefinder cameras like the Leica and Contax were preferred by many professional photographers as SLRs were slow and clunky in operation, most featuring dim waist level finders, non-instant returning mirrors, and uncomfortable ergonomics. For the pro that demanded through the lens composition, the Exakta was a great choice. It was a built to a very high quality standard, had many features not found on other SLRs, and had a very large selection of available lenses and accessories. There was also very little competition. KW had just released the Praktina and Zeiss-Ikon had the Contax SLR, but neither had the support Ihagee did for the Exakta.

When it was announced that a medium format Exakta was on the horizon, people were notably excited as none of the current 6×6 SLRs that existed with professional level specifications, or had the reputation of Ihagee. In December 1953, Modern Photography published the following preview of the camera. This was meant only as a preview as the article mentions there was no time to film test the camera. Still, the preview comes across as positive, going through the camera’s long list of features and promising future features like an eye level pentaprism. Although they don’t specifically say it, anyone reading this preview in 1953 would have assumed a full test was soon to follow.

Sadly, a follow up test in Modern, or any other American publication never happened. As was the case with the horizontally traveling Exakta 6×6, construction of the new camera was plagued by quality control challenges. Parts of the camera, specifically the film transport had to be changed from the original prototypes shown in 1952. Another change to the camera’s lens mount was made, making it larger to better support larger lenses without vignetting, however this rendered any lenses made for the original model incompatible with the new model. This meant that between the Vest Pocket, Kine, horizontal Exakta 66, and the vertical Exakta 66, all four models had four different lens mounts.

Although production of the new model did start in 1953, constant changes and other delays meant that only 118 were ever delivered that year. Things improved slightly in 1954, with an estimated 2250 cameras built, but this was a far cry from the anticipated 10,000 that Ihagee had planned to build annually. Before 1954 was over, production on the camera was halted in an attempt to re-evaluate the problems and come up with a solution. Consultants from the Institute for Electrical and Mechanical Precision Mechanics at the Technical College of Dresden were brought in and evaluated the construction of the camera and what could be done to improve it. The result of their findings was that the design of the camera was fundamentally flawed and the whole camera would need to be re-designed in order to attain the desired quality standards.

It seemed that the idea of a medium format Exakta was cursed as no version of the camera ever lived up to the quality of the 35mm Exakta. How such an otherwise capable company like Ihagee was able to build the 35mm Exaktas with such a high level of quality, but fail so miserably with the Exakta 66 is still a mystery that will likely never be answered. If I had to take a guess, I would suspect that meddling from the East German Soviet controlled government or supply chain issues also caused by the government possibly had a hand in it. The Kine Exakta was created before the war and likely didn’t face the same challenges that cameras built after the war did. This is just my own speculation however, as I have never read this from any other reputable experts, but it does seem plausible.

It is unclear to me if and when production resumed after 1954. Ads for the camera appeared in American publications throughout 1955, and at least one Exakta price list dated June 1958 still showed the camera for sale. It seems unlikely to me that such a troubled camera would still be in production for so long after it was determined to be fundamentally flawed, so perhaps there was still enough new old stock to supply dealers with new cameras for anyone who wanted one.

Throughout the 1950s, Ihagee was run entirely by the Soviet controlled East German government. Around 1959, Johan Steenbergen returned to Germany with the hope of reviving his own company. He started Ihagee West, located in West Berlin and started work on an all new 35mm SLR which would eventually become the Exakta Real from 1966.

The new camera hoped to improve the ergonomics of the original model and bring it’s feature set more in line with contemporary SLRs. The camera still shared a similar, but less angled trapezoid shape, had twin shutter releases both on the left and right side of the camera, used an all new and much larger bayonet lens mount, supported interchangeable lenses, and added a variety of modern features like an instant return mirror and film advance lever.

Production delays, reliability concerns, and an extremely high price tag doomed the Exakta Real, causing very few sales, making the camera extremely rare today. Steenbergen would pass away a year after the new camera’s release, and any hope of an updated model would die with him. In 1970, Ihagee West would license the Exakta name and use the Exakta Real’s bayonet lens mount to Cosina of Japan to make the Ihagee Exakta Twin TL. A version of the camera called the Twin TL 42 was also created but used the M42 “universal” screw mount. This camera was Exakta in name only and was not manufactured by Ihagee.

For the East German version of Ihagee, in 1970, the company would be merged into VEB Pentacon and the companies products would slowly be discontinued. One last Exakta model called the Exakta RTL 1000 was built on the body of a Praktica SLR and although it shared the same lens mount, it was a completely different camera and was plagued with reliability concerns, selling poorly.

Although completely unrelated, in 1985, the Exakta 66 name would be used once again, this time by the West German version of Ihagee. This new Exakta 66 was very similar to the Pentacon Six SLR, and shared the original Praktisix bayonet lens mount. If you count this version of the Exakta 66 as part of the original Exakta lineage, this was the fifth Exakta camera produced, with the fifth unique lens mount!

The Exakta 66 was somewhat popular, staying in production until at least the early 1990s, with an estimated 5000-6000 produced. Like many cameras of this era, the exact end of production is not clear as after the fall of the Berlin Wall, unsold new inventory continued to be offered for several years after.

Today, Ihagee Exakta cameras of all types are sought after by collectors. Their good looks, reliable operation, and long list of features make them for capable shooters, even today. These were very expensive cameras when new and only the best lenses were ever made for them, so when finding one in working condition, you can be certain it’s capable of excellent images.

As we can see, although Ihagee did a great job with it’s 35mm cameras, it struggled with medium format. All models, from the pre and postwar horizontal transport and vertical transport Exakta 66s suffered from unreliable operation and poor sales. All medium format Exaktas are rare and extremely hard and expensive to find today. When they are found, they rarely work, so if you are lucky enough to not only find one, but one in working condition, consider it a once in a lifetime opportunity and you should strongly consider picking it up. In the likelihood it is outside of your price range, be sure to alert any deep pocketed collectors you may know as they likely would be interested!

My Thoughts

I have many Exaktas. They’re not exactly hard to come by as millions were made (okay, I am just assuming there were millions made because they’re so common). One time I was gifted an entire box of broken ones which added to the 10-12 I already had. Then, I came across a selection of several Vest Pocket Exaktas gifted to me by a dear friend. But for how common these Exaktas are out there, the 6×6 versions have eluded me. Their rarity and poor reputation for being in working condition meant that if I ever wanted to review one, I’d likely have to borrow one from a friend.

That opportunity came in June 2022, when I went to visit fellow Camerosity Podcast host, Paul Rybolt at his home. In Episode 26 of the show, Paul talks about the camera show in Columbus, Ohio he had went to where auction prices went absurdly high, but later bought a Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex TLR and Exakta 66, so when I went to visit Paul, I wanted to check out both cameras in person.

Although the Exakta 66 does have a similar shape to other medium format SLRs with a waist level finder, almost everything about the camera is unique and would intimidate even the most experienced collector (me). A familiarization through the camera’s manual is definitely in order when using this camera as some of the controls aren’t exactly intuitive.

Before I go any farther, let’s talk about the weight. Tipping the scales at a massive 1562 grams with the 80mm f/2.8 Tessar mounted, the camera is extremely heavy. I guess this shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone as the 35mm Exaktas are made of large chunks of brass and glass, and can easily top the weights of other 35mm SLRs of the era. At a weight of nearly 3.5 pounds, this is definitely not something you’d want falling on your foot. A sturdy neck strap would also be a requirement as carrying this camera around on long shooting sessions would likely cause a great deal of fatigue.

Starting with the camera’s right side, there are a variety of controls, most of which are self explanatory, some not. For users of 35mm Exaktas, we see two familiar shutter speed dials, one for the fast speeds from 25 to 1000 plus B and T. Like the 35mm camera, lift up on the dial and rotate it in the direction of the arrow until your chosen speed lines up with a little red dot.

Near the bottom is what Ihagee called the Delayed Action Knob which controls both the slow shutter speeds from 1/10 to 12 seconds indicated in black numbers, but also the self-timer in red numbers. All Exaktas from the original Vest Pocket Exakta B, through the Exakta VX series in the 1960s use a similar design in which you must first set the fast speed dial to either T or B mode to use the slow speeds. The delayed action self timer works at any fast speed, but for how common Exaktas were in the mid 20th century, still confuses me each time I use the camera. In my review for the Night Exakta B, I typed the following describing how each are used:

Using the Exakta’s Delayed Action Knob

Whether you are using the self-timer, a slow shutter speed, or a combination of the two, this knob must always be wound as far as it will go. Also, you must always cock the shutter first before turning this knob as it will not hold it’s position if the shutter is not ready.

As you turn the knob, it’s resistance will increase, but it is important that you always turn it until you feel a firm stop, indicating it has reached it’s limit. Failure to turn this knob all the way can cause the mechanism to not work correctly. The amount you have to turn this knob depends on how it was used previously.

Note: Each of the following three situations assume the shutter is already cocked and the delayed action knob is already rotated as far as it will go.

To use the self-timer with a fast speed, select any speed on the fast speed dial from 1/25 to 1/1000 and then lift and rotate the outer part of the delayed action knob until one of the red numbers lines up with the black dot in the center of the knob and then let it drop back down into position. When firing the shutter, the shutter will fire at whatever fast speed you have selected after an approximate 12 second delay. It does not matter whcih red number you select, for the self timer, the delay will always be about 12 seconds.

To use slow shutter speeds from 1/10 to 12 seconds, you must first set the fast shutter speed dial to either B or Z, then repeat the previous step, except instead of choosing one of the red numbers, you choose one of the black numbers from 1/10 to 12. When firing the shutter, the first curtain will immediately open and remain open for the duration of whatever slow speed you’ve chosen.

To combine both a slow shutter speed with the self-timer, repeat the previous step, except instead of choosing one of the black numbers, choose a red number from 1/10 to 6 seconds. When firing the shutter, an approximate 12 second delay will precede the shutter opening for the duration of whatever red speed you’ve chosen.

Back to the right side of the camera, starting at the top there is the manual resetting exposure counter. Unlike most medium format SLR and TLRs with exposure counters, the one on the Exakta 66 doesn’t automatically reset after loading in a new roll of film. Below and to the right of the shutter speed dial is something called the “Reverse knob for exposure counter”. As I did not have the opportunity to shoot this camera, nor does the Exakta 66’s manual explain what this does, I can only assume it’s another way to reset the exposure counter.

Next is the large combined film advance knob that serves multiple duties, including raising the reflex mirror into taking position, cocking the shutter, and incrementing the exposure counter. The knob has two wings on the top for adding grip while turning it, which is good, as even without film in the camera, required quite a bit of force to turn. Perhaps this complex sequence of events is part of the struggles Ihagee had with the film transport in this camera. Below and to the right of the film advance knob is a locking lever for the shutter release. Finally, not on the actual side of the camera, but the side of the mirror box above the lens is a locking lever for the ground glass magnifier.

On the left side is a surprisingly large dial for adjusting the flash sync delay, allowing for full customization of your flash sync setting for everything from electronic flashes, to whatever bulb you may be using. Beneath is one of the two camera’s tripod sockets. This one appears to be a 3/8″ socket with a 1/4″ adapter in, which some previous owner probably installed. I don’t fully understand why you’d want two locations for tripod sockets on a camera that shoots 6cm x 6cm images, but perhaps Ihagee foresaw a mask that could do smaller 4.5cm x 6cm images in the future.

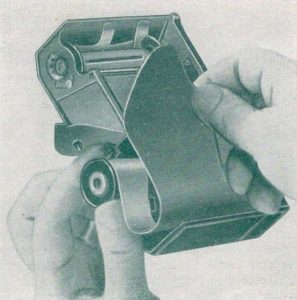

To the right of the tripod socket is something that definitely falls into the RTFM category, which is the film magazine lock lever. This long chrome lever normally sits in a recess in the body pointing down. To release the magazine, lift up on the bottom edge of this lever and rotate it counter clockwise until the back literally falls off. It goes without saying you should support the magazine back before releasing it as it would be pretty unfortunate for it to hit the floor.

On the top of this side of the film magazine is a film key which is used to help tension film while installing a new roll inside the magazine, but below it, my favorite feature of the camera, which is a triangular film reminder “cheat sheet”. This little window works by having a piece of black wax behind a semi transparent film, which is covered by a transparent window. With a stylus or some other sharp object, you can write on this window, and pressure from the tip, makes the semi transparent film come in contact with the wax layer beneath it, leaving an imprint. You can write on this anything you want, like what type of film you’ve loaded, speed, how many exposures are remaining, etc. When you no longer need your reminder, rotating the metal dial beneath it, swipes a wiper behind the semi transparent film, separating it from the wax layer, effectively erasing what you wrote. I remember drawing boards like these when I was a kid, as a sort of primitive “Etch a Sketch” but I’ve never seen this implemented in a camera.

Around back, there are two things, well one thing and one large missing thing. The large missing thing of course is the strange black void in the middle of the back. This strange design element is clearly what’s behind the film pressure plate in the magazine, but otherwise serves no purpose. The Exakta 66’s manual makes no mention of it, so I wonder if there wasn’t some kind of future upgrade planned for this.

To the left of the void is what the manual refers to as the “Window for film wind indicator”, which seems to be some kind of feeler device that detects the start of the film on a new roll of film. The manual describes it’s operation as after loading in a new roll of film, first turning the film key seven full rotations until a needle visible in the feeler jumps about 2-3 mm to the right, at which time you must rotate the film key 5 mm “more”. To be honest with you, I have no clue how this works as I didn’t get a chance to shoot film in this camera, but had I did, there’s a very good chance I still would have struggled with it. It is clearly a strange setup, giving further insight into why these cameras struggled so much with their film transport.

According to the manual, loading film into the camera is a multi-step process that is unlike any other camera I’ve seen. Sadly, without having shot film in this camera, I can’t comment on how it’s done, but the manual clearly spells out nearly a dozen steps, the first of which is ensuring the exposure counter is manually set to an “F” position.

Removing the back is simple enough by rotating the long lever on the camera’s left side. With the back off the camera, we see the film compartment showing off the film gate and cloth shutter curtains.

In the image to the left of the film back, the take up side is on the right. The supply side is not visible as it is behind the roller on the left side of the back.

The image to the right comes from the Exakta’s user manual and shows the supply side goes under a hinged metal piece, behind the roller. The film must make a 180 degree turn with the black side of the paper facing away from the pressure plate. Secure the paper leader to the take up spool and manually rotate it until you are sure it is securely attached.

The most confusing part to me is the function of the film key which has three dots on it. The manual suggests that you can only advance the film when the key is turned away from one of the dots. I didn’t try this myself, but perhaps it pops out and allows easier grip to spin the take up spool in the film compartment to advance the film. Perhaps it’s more intuitive in person, but unless I come across another Exakta 66, I’ll likely never know.

Overall, the film loading process is probably one of those things that with repeated use, you’d get used to, but reading through vague instructions written by someone who didn’t actually do it himself, is an exercise in frustration, so I should probably just move on. I’ll leave you with this, it’s certainly not intuitive for the first timer.

The bottom of the camera has a second tripod socket like the one on the side that has a 1/4″ adapter in a 3/8″ hole. In front of the tripod socket, beneath the mirror box is a metal foot that stabilizes the camera when set on a flat surface. Finally, written in paint on the body covering are the words “USSR Occupied” which was typical of East German cameras of this period.

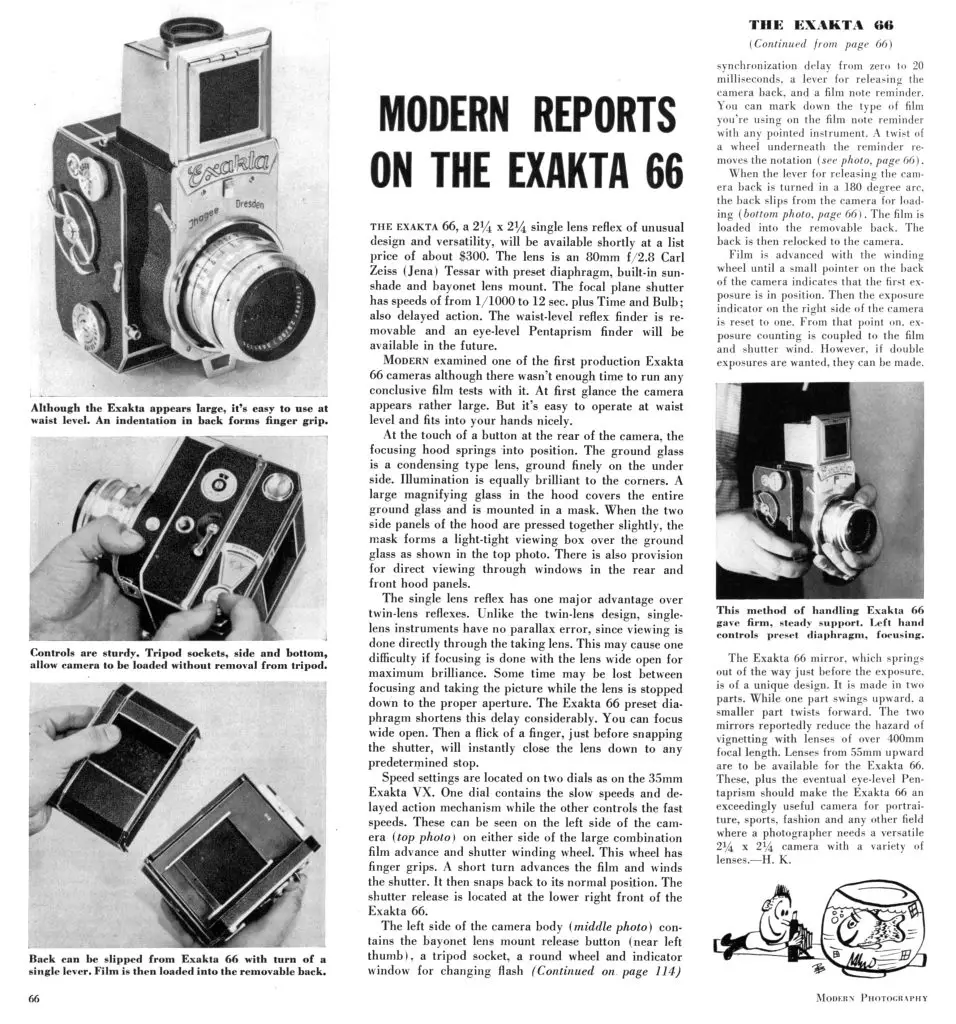

The Zeiss Tessar lens is similar to those found on other cameras in that it is a preset design, but it lacks an automatic aperture. This means that pressing the shutter release does not communicate back to the lens to stop down to your chosen f/stop. You can preset the aperture, by pulling back on the chrome ring behind the aperture ring and turning it to your chosen f/stop. With it here, you can release the preset ring and turn it back so the diaphragm is wide open. With the lens wide open, you can compose your image through the viewfinder allowing the maximum amount of light through. Then right before firing the shutter, all you have to do is manually turn the aperture ring until you feel it stop at whatever preset f/stop you previously selected. I’ve used preset lenses before and it always sounds more complicated than it really is. It’s definitely slower than when using lenses with automatic diaphragms, but you do get used to it. Nearest the body is the focus ring, which has a thick metal ring around it making focus changes simple, and finally, a depth of field scale nearest the lens mount.

The Exakta 66 uses it’s own bayonet mount that is incompatible with lenses designed for the earlier horizontal Exakta 66 or both the 127 and 35mm Exaktas. Exchanging lenses requires you to press back on the lens release tab on the side of the mirror box near the 3 o’clock position around the mount. With the lock released, rotate the lens counterclockwise until it lifts off. Sadly, very few lenses were made in this camera’s mount. I believe only two other focal lengths, both telephoto, were ever made, but had the system been more successful, there likely would have been many more lenses.

With the lens off, you can see the two piece reflex mirror. The top half is larger than the bottom, but when working properly, the two should line up to each other making a single large reflective image. This design was chosen as it minimized body shake and allowed for a shorter time for the reflex mirror to swing out of the way.

All Exaktas, including the 35mm versions started out with a waist level finder. Like most WLF cameras, flip up a hood, and look through a ground glass that reverses the image left to right. Unlike TLRs that often have this style of viewfinder, SLRs see through the taking lens, so there no worry about parallax correction. When it was designed, the Exakta 66 was supposed to have other options for the viewfinder, including a pentaprism finder, but none was ever developed. You can still removed the lens hood on the Exakta 66, but without anything else to swap to, there really isn’t a point.

Also like other cameras with WLF finders, the Exakta 66 has a folding magnifying glass which allows you to see the ground glass up close for precision focus. This flip up lens is on a metal plate that locks into place blocking out extraneous light from entering the viewfinder. This is one area in which the production Exakta 66 differs from the 1952 prototype version mentioned earlier in this article. That version had a hinged glass that “floated” above the ground glass and did not block out light.

As this camera was not functioning, I never got a chance to see through the viewfinder. In the image above with the lens off, you can see the two piece reflex mirror which was not moving into it’s correct position to allow me to see through the viewfinder. Had I been able to see through it, I suspect the image would have been decently bright in the center, but showing heavy vignetting in the corners.

Waist level finders of all types from the early to mid 1950s were often quite a bit darker than those from cameras that came later as they did not benefit from laser etched Fresnel patterns which brighten the image and even out the corners. Had I been able to shoot this camera, I probably would have been able to see a decent image outdoors in good lighting, but probably would have struggled indoors.

The Exakta 66 is a fascinating example of a camera built by a company with high aspirations, but for one reason or another failed to deliver. Strangely, the company’s 35mm cameras were highly successful but their attempts at medium format seemed to run into constant problems. Film transport issues, a confusing operation, four lens mounts on four different models, and a high price likely all contributed to it’s failure.

Of course, when you have a camera that didn’t sell well, it means there aren’t that many out there, and that drives up prices. Finding examples of the Exakta 66 is difficult, and when they do show up for sale, they are extremely expensive. This particular example didn’t work, and even if it did, it likely wouldn’t have stayed that way for long. I am unsure if there are any technicians out there willing to give a camera like this a CLA, but if there is one out there, that is properly working, and you’re willing to share your experience and perhaps some results, please let me know!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Exakta_66_(vertical)

http://elekm.net/pages/cameras/exakta_66.htm

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/stories/47714-exakta-66-vertical

Wow – likely the most detailed review of this camera ever published. Thank you, Mike! I’m puzzled by the film transport problems, as both Mamiya and Fuji made several models using the even-larger 120 film, and friction (as opposed to geared) film advance mechanisms, with zero history of problems. Can anyone shed some light on this?

Mike, Gejza Dunay a/k/a Cupog in Slovakia might tackle a CLA on the 66 for you … but you’ll have to pay import and exxport duties both way on the shipment. FWIW, ol’ buddy ….

I’ll pass that suggestion onto Paul, but my guess is he already has enough in this camera, he just wants to sell it as is. As you mentioned, while Gezja does do good work, it would add considerable cost to get the camera to him and back.

Do the lenses for these stop down automatically? I don’t see the shutter button on the lens like the automatic lenses for the 35mm Exakta. Or does this camera use preset lenses? That would be a bit dated in the 1950s.

These lenses are all preset lenses. I do not believe there were any semi-automatic lenses made for the Exakta 66. Considering this camera was developed between 1951 and 52, and first released in 1953, preset lenses were still pretty common. Semi and fully automatic lenses did not become more common until later in the decade. Although it wasn’t a whole lot later, remember that the evolution of SLRs (35mm and medium format) happened very quickly…what was state of the art in 53 was outdated in 55, and those cameras were out dated again by 57.