This is the Nikon F3, a 35mm single lens reflex camera produced by Nippon Kogaku of Tokyo, Japan between the years 1980 and 2001, making it the longest list Nikon camera ever made and one of the longest ever produced cameras in history. The Nikon F3 was the third in Nikon’s professional F-series of SLRs, but unlike the F2 which was an evolutionary upgrade to the original F, the F3 was a completely new model, designed from the ground up with a more compact and lightweight body, an electronic shutter, and in body TTL metering and aperture priority automatic exposure. The Nikon F3 would be the last professional manual focus SLR which helped to maintain it’s longevity. Despite continued advancement of the line, the Nikon F3 remains an extremely popular camera today for collectors and shooters alike and is frequently mentioned on lists of the best cameras ever made.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/1.8 Nikkor coated 6-elements in 4-groups + others

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet

Focus: 1.5 feet / 0.45 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Interchangeable SLR Pentaprism and Interchangeable Viewing Screens, 100% Field of View, 0.8x Magnification

Shutter: Horizontally Traveling Titanium Foil Focal Plane

Speeds (Auto): 8 – 1/2000 seconds, step less

Speeds (Manual): T, B, X, 8 – 1/2000 seconds, 1/60 Mechanical Speed

Exposure Meter: Silicon Photo Diode Center Weighted TTL Meter and Aperture Priority AE

Battery: (2x) 1.5v SR44/LR44 Silver Oxide Battery

Flash Mount: Nikon AS-2 Style Hot Shoe M and X Flash Sync, 1/80 X-sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Viewfinder Blind, Shutter Lock, Multiple Exposure Lever, Mirror Lock Up

Weight: 925 grams, 710 grams (no lens), 598 grams (no lens or prism)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/nikon_pdf/nikon_f3.pdf

How these ratings work |

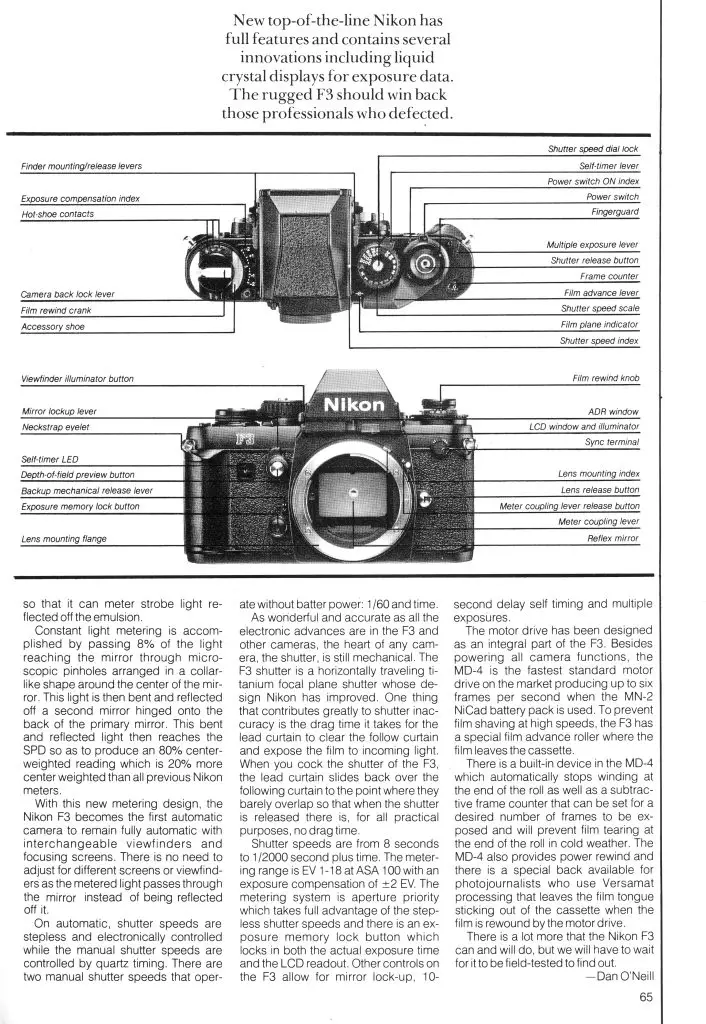

The Nikon F3 was the first major re-design of the professional Nikon F series since 1959. Although incorporating a huge amount of new technology, many pro photographers then didn’t embrace the upgrades. The Nikon F3 was very controversial upon it’s release but with the benefit of hindsight today, has proven itself to be worthy of it’s reputation. Loaded with features like Aperture Priority Auto Exposure, an electronic shutter, and a much more modern film compartment, the F3 is the best of old and new, a manual focus, professional level SLR with great ergonomics, a compact size, and support for the world’s greatest lens system. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for one of the longest produced SLRs ever made, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.0 | ||||||

History

When Nippon Kogaku released the Nikon Reflex in 1959, it signaled a seismic shift in professional photography. The era of the 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera had officially begun, and makers of all other types of cameras were put on notice. Certainly, for such a historically significant camera to have the influence and success that it did, it must have pioneered some type of revolutionary new technology, or had a design or feature never before seen on another camera, right?

When Nippon Kogaku released the Nikon Reflex in 1959, it signaled a seismic shift in professional photography. The era of the 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera had officially begun, and makers of all other types of cameras were put on notice. Certainly, for such a historically significant camera to have the influence and success that it did, it must have pioneered some type of revolutionary new technology, or had a design or feature never before seen on another camera, right?

The most significant feature the new Nikon camera wasn’t it’s shutter, or it’s pentaprism, or it’s instant return mirror, or it’s quick change bayonet mount. No, in fact, almost nothing in the first Nikon SLR was completely new. Every one of the features mentioned in the previous sentence appeared on cameras that came before it. SLRs weren’t even new as models like the Ihagee Exakta predated the Nikon Reflex by over 20 years.

The thing that made the camera great wasn’t any one specific piece of the camera. It was equal parts of uncompromised build quality and a complete package designed with the professional photographer in mind, only having the features that they needed, and nothing else.

To understand how Nippon Kogaku was able to be so successful with their first SLR, you need to understand the company’s origins. Founded in 1917, the company’s full name was Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha which translates to Japan Optical Industries Co., Ltd., the company’s primary function was to built optical equipment for Japan’s military, specifically their navy.

Other than a few side projects here and there, Nippon Kogaku did not make a single product for commercial sale until 1948, so for the first three decades of their existence, their only customer was the military, and when you build something for the military, it has to be good. Without the need to compete for the public’s buying dollars, you didn’t need to consider how much something would cost. In those days, when Nippon Kogaku built something, there were no shortcuts or consumer focus groups, everything had to be perfect, every single time.

This philosophy of uncompromising quality at any expense stuck with the company after the war, and when the first Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses went on sale, they were heads and shoulders above the competition in terms of quality. Although Nippon Kogaku’s Nikon rangefinder cameras saw some success, they represented only a small percentage of the company’s portfolio. Lens sales were the bread and butter of the company, and their reputation among professional photographers grew tremendously throughout the 1950s.

Nippon Kogaku was working on the Nikon S2 when Ernst Leitz released the M3, and upon it’s release, the whole world was taken aback at how good it was. The management at Nippon Kogaku was so impressed, they delayed the release of the S2 to improve it, adding a film rewind knob and some other refinements that the original prototypes didn’t have.

After the release of the Nikon S2 in 1955, the company quickly got to work on it’s successor, the Nikon SP. While the Nikon SP offered many improvements over the S2, it still was no match for the Leica M3, and Nippon Kogaku knew this. Masahiko Fuekta, Nikon’s primary engineer in charge of new product development realized that the Leica M3 represented the pinnacle of 35mm rangefinder design. He believe that continuing to compete head to head with Leitz in the rangefinder market was not a smart move and saw a recent rise in popularity of 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras as a direction the company should pursue.

Fuketa knew that the new camera would need a wider body and that it needed room for both a larger lens mount and pentaprism viewfinder, but beyond that, he didn’t know exactly how to make a Single Lens Reflex camera. Not wanting to have to play catch up with Leitz or anyone else like they did with the M3, Nippon Kogaku leveraged their relationships with American photojournalists who came and went through their Tokyo offices.

During the Korean War and after, Nippon Kogaku developed relationships with a huge number of highly respected photographers from LIFE Magazine and a huge number of other publications. Fuketa solicited feedback from these photographers on what they would want to see in a new SLR. He and Nippon Kogaku’s management listened intently on what it would take to get people to hand in their Leicas and Rolleiflexes and consider a 35mm SLR and made that a priority with the new camera.

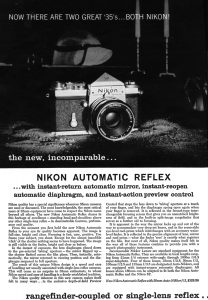

Their plan worked, and upon it’s release, the Nikon Automatic Reflex (it was not called the Nikon F until later) incorporated many of these wishes into the final design. Instead of innovative new features, the camera emphasized rock solid reliability, it supported a motor drive, similar to that of the KW Praktina, and of course it supported a large number of the company’s best Nikkor lenses. Even if someone were to match the Nikon SLR feature for feature, the company’s reputation as a lens maker was by far, what differentiated them from the competition the most.

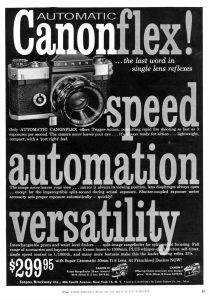

The Nikon Reflex took the world by storm, and within a couple of years, it was the best selling professional camera in the world. By comparison, Nippon Kogaku’s biggest competitor was Canon, and their Canonflex SLR which was also targeted at professional photographers was dead on arrival. Canon made two critical mistakes with the Canonflex, they designed the camera with features like a bottom trigger film advance that they thought people wanted rather than what they actually did, but also they had a very poor selection of lenses upon the camera’s release.

In the early 1960s, demand for Nikon SLRs was so great, that the company had no choice but to wind down it’s rangefinder division. While SLR’s were becoming the preferred format of choice for the pros, amateur and beginning photographers still preferred rangefinders, so there was still demand for those, but Nippon Kogaku couldn’t physically keep up with SLR demand while devoting resources to anything else. By 1962, Nippon Kogaku was an SLR only camera maker.

Over the course of the next decade, no one competed with the Nikon F. Even Canon, who tried and failed, allocated their time and resources toward mid level SLR models and their rangefinders. The hierarchy of Japanese camera makers in the 1960s was Nikon at the top and everyone else below them.

This was both a blessing and a curse, as not only was the company not able to produce much else, but it also limited their ability to improve on the Nikon F and address some of it’s shortcomings. Although still the preferred 35mm camera for the professional, things like the lack of a hinged back, inelegant design of the Photomic metered prisms, and limited 1/1000 top shutter speed were getting long in the tooth. By the mid 1960s, nearly every other SLR model on the market improved upon these features.

Work began on the successor to the Nikon F in September 1965. The new camera would continue with the same priorities as the original, extreme quality control and a dedication to the needs of the professional photographer. When it was released in September 1971, the Nikon F2 improved the shutter’s top speed to 1/2000, the Photomic prisms were updated also moving the battery chamber to the camera body’s base plate, and the removable back was replaced by a more traditional hinged design. The Nikon F2 had a few other minor functional and ergonomics improvements, but didn’t offer any significantly new features. It merely refined and updated the original camera to more closely match what people wanted in the early 1970s.

As did the original, the Nikon F2 was very successful, quickly taking the place a top the best selling cameras of the 1970s. Nippon Kogaku was successful at improving the things people most wanted to see, while retaining the rock solid build quality and reliability of the original, and maintaining full support for some of the world’s greatest lenses.

Unlike the 1960s however, by the early 1970s, the Nikon F2 had some serious challengers. Canon re-entered the professional 35mm SLR market in March 1971 with their new Canon F-1, Minolta released their pro-level X-1 in April 1973, and even Olympus attempted to chip away at the pro market with the very excellent advanced consumer OM-series.

In the consumer market, electronic shutters with infinitely variable auto exposure speeds were becoming the norm, LEDs were replacing the mechanical needles in viewfinders, and both camera bodies and lenses were increasingly employing lighter weight plastics instead of the heavy brass of cameras from the previous decades. The good news for Nippon Kogaku was that electronics and lighter weight plastics went against the professionals who preferred bullet proof reliability, but Nippon Kogaku knew that their competitors would continue to invest in more modern technologies, and this was something the company couldn’t ignore.

Unlike with the F2 in which development took a couple of years to start, Nippon Kogaku started looking forward to their next professional SLR immediately after the release of the F2. With each release of a new product from that point forward, new features were being auditioned for what would eventually become the Nikon F3. The Nikomat/Nikkormat EL’s electronic shutter and auto exposure foreshadowed a much more advanced camera. When new Nikkor lenses that supported Automatic Indexing were released in 1977, it signaled an improvement in how lenses would couple with meters of future cameras. Shortly after the release of Ai lenses came the Nikon FM and FE SLRs which had more compact bodies which employed lighter weight plastics in their design.

Design for the F3 officially began in March 1977 with an emphasis put on high quality and high reliability, ease of operation and versatility, and automatic operation. Nippon Kogaku envisioned a camera that for the first time would be a big departure from the formula created with the first Nikon F in 1959.

Early prototypes of the F3 were completed in November 1978 and show a body very similar to that of the F2. The first two mockups in the gallery above clearly show a shutter speed dial with a top 1/2000 speed and a green “A” confirming an automatic exposure mode. The smaller prisms also confirm an in body TTL meter, unlike the F and F2 where the meters were part of the viewfinder. The third mockup is the only one showing the body design with the F3’s finger grip to the left of the lens mount and a flatter prism that closely matches the final design.

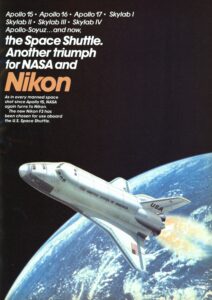

Nippon Kogaku was making a gamble by including a large amount of electronics and new technology in their new camera and they knew that some people might not welcome the new model as warmly as the F2 was received, but the company received some validation in the fall of 1978, when NASA tapped Nippon Kogaku for a new camera to be used in the first launch of NASA’s new Space Shuttle in 1981.

NASA provided exact specifications that the camera would have automatic exposure control and that the camera should be able to take a total of 250 pictures and be easy to change. The new camera would need to be completed within a year and a half. Building on their prior experience with making cameras for NASA’s Apollo program, Nippon Kogaku produced two cameras, a “big” version with an interchangeable 250 exposure magazine back, and a “small” version that had a 72 exposure magazine. The cameras were both delivered to NASA as promised in May 1980 and the small 72 exposure camera went up on the Space Shuttle Columbia as part of STS-1 on April 12, 1981.

For the rest of the world, the Nikon F3 made it’s debut in March 1980 to equal parts excitement and trepidation. That such a highly anticipated professional camera embraced auto exposure, battery dependent electronic shutters, and weight saving materials legitimized these new features, but also terrified photographers whose livelihoods depended on their cameras working 100% of the time, no matter the conditions. Initial response from the pros was that they would stick with their fully mechanical F2s for as long as they could, but the F3 opened the door to a new segment of advanced amateurs, those who were more tolerant of modern features, while not necessarily needing to support their families through their work.

The earliest article I could find using my regular source of Modern and Popular Photography magazines comes from Pop Photo’s April 1980 issue, effectively functioning as a technology preview, and offering no real world experience or editorial commentary.

Regardless of which side of the electronic camera fence you sat on, excitement was very high for the new Nikon as article after article was published about it. Every editor from every magazine including Herbert Keppler himself weighed in on the new camera. The following sequence of articles cover everything from a first look, to a comprehensive lab report.

Herbert Keppler’s preview from April 1980

Popular Photography’s first hands on test from May 1980.

Modern Photography’s Modern Test from June 1980.

Herbert Keppler compares the new Pentax LX to the Nikon F3 in February 1981.

Lab Report April 1981

Advertisements for the Nikon F3 highlighted it’s use on the Space Shuttle missions and capitalized on Nippon Kogaku’s reputation with professional photographers. In one of the ads below, the entire family of Nikon SLRs is presented with the F3 prominently up front.

At the time of it’s release the price of the F3 was listed with f/1.8, f/1.4, and f/1.2 Nikkor 50mm lenses for $1102.50, $1174.90, and $1345 respectively. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $4015, $4280, and $4900 today. I could not find a price for just the body by itself.

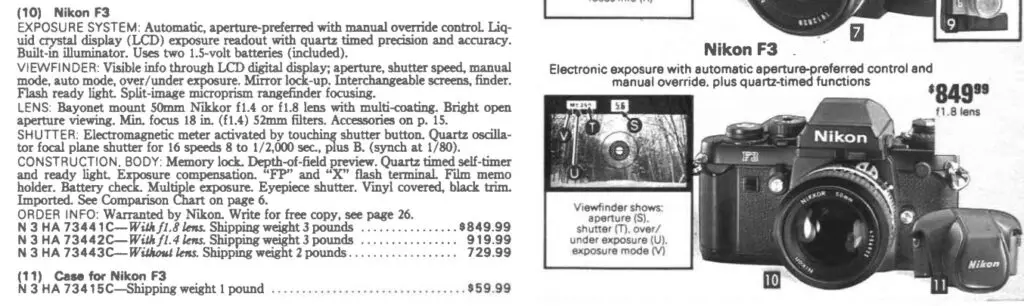

As was common practice back then, the street price someone would actually pay was considerably less than the stated manufacturer’s retail price so I checked the 1981 Sears Camera Catalog and equipped with the f/1.8 and f/1.4 lens the camera still sold for $849.99 and $919.99 respectively. Admission to the F3 club was still very high, no matter how you bought the camera.

The Nikon F3 was Nippon Kogaku’s flagship model and despite initial concern about it’s use of battery dependent electronics and some weight saving materials, proved to be a tremendous success. The camera enjoyed an unusually long life span, staying in production until 2000, outliving it’s successor, the F4, and lasting more than half way through production of the F5.

Throughout it’s life, many revisions and alternate versions of the F3 were produced. One of the first changes came in March 1982 with the introduction of the “High Eyepoint” DE-3 viewfinder which improved visibility through the viewfinder for people wearing glasses or goggles. When sold with this viewfinder, the F3 was called the F3HP with the body still labeled “F3” and the letters “HP” appearing on the prism.

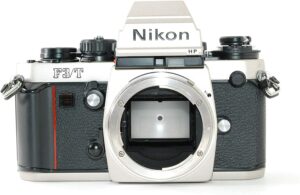

Later that same year, the titanium body Nikon F3/T was released which featured a titanium viewfinder, titanium top and bottom plates, and a titanium door, increasing wear resistance and lowering the camera’s weight by about 20 grams. Initially, the F3/T was offered in a more natural titanium champagne colored body, and later, in black versions. The champagne version was discontinued in 1985 and would be the only non-black versions of the F3 made.

A “press” version called the F3P was released in 1983 which included additional weather sealing, O-ring gaskets, the MF-6 Auto Film-Stop Back, Type B Matte focusing screen, a modified Titanium DE-5 pentaprism with ISO-type accessory shoe and no eyepiece blind, rubber-covered waterproof shutter release with a modified lockout and no cable release threads, a round frame counter window with white numerals, and an extended shutter speed operating knob for easier operation in cold or wet environments. The F3P lacked a film door release lock, self-timer and multiple-exposure lever.

In 1983 with increasing interest in auto focus by competing brands, a camera called the F3AF was made which added support for two specially designed Nikkor AF lenses made specifically for this camera, the AF Nikkor 80mm f/2.8 & AF Nikkor 200mm f/3.5 ED IF. With either of the two lenses mounted and the F3AF’s special DX-1 finder, the camera offers true TTL auto focus performance. Both of the auto focus lenses communicate with the body through additional electronic contacts around the edge of the lens mount.

Although only two lenses were ever made that supported full autofocus with the F3AF, when used with Series E manual focus lenses with a maximum aperture of f/3.5 and faster, or later Nikkor AF lenses, the camera could still be used in focus assist mode, with over and under focus LEDs visible in the viewfinder. The Nikon F3AF could also work with all regular manual focus lenses too.

The F3AF remains one of the least common versions of the F3, likely because Nippon Kogaku knew the technology wasn’t ready for prime time yet. That the only two lenses that worked with it had longer focal lengths of 80mm and 200mm suggested it needed the shorter depth of field of a longer lens to accurately detect focus. Using the system in the F3AF, accurate auto focus with 50mm and shorter lenses probably wouldn’t have worked well. The technology was almost certainly a way for Nippon Kogaku to test the waters with the system they were developing for future auto focus SLRs.

In the mid 1990s, with the Nikon F3 well over a decade old, a couple Japan only special edition cameras were produced called the F3 Limited and F3 Classic. The F3 Limited was very similar to the F3P, but without the MF6B back and with a non-interchangeable focus screen. The F3 Classic is even rarer, made for the 50th anniversary of Nippon Kogaku’s relationships with their oldest distributor, Ando Camera. The Classic is the same as an F3/T with special gold engravings on the body and f/1.2 lens, and comes in a special presentation box.

The final variant of the F3 wouldn’t be released until near the end of the camera’s lifespan. In 1998 a model called the Nikon F3H was produced for the Nagano Olympics in Japan. The Nikon F3H was a high speed version that could shoot up to 13 exposures per second for sports photographers. In order to accomplish this feat, the moving reflex mirror from the regular F3 was replaced with a fixed pellicle mirror that diverted 30% of light into the viewfinder and 70% to the film plane without having to move. By eliminating the need for the shutter to wait for the mirror to flip up before each exposure, the camera could expose more frames per second. Similar versions of the original F and F2 had been released employing a similar pellicle mirror.

Although originally intended for sports photographers who might need to capture sequence photos in quick succession, Nikon would later admit that the primary reason for the camera’s release was to compete with Canon’s similar high speed model released the year before, which could shoot up to 10 exposures per second.

If you were to collect each of the Nikon F3 variants above, your collection would only be complete if you limited yourself to film cameras. With such a long lifespan, in 1991, the Nikon F3 crossed over into the digital realm with a camera called the Kodak DCS 100. The DCS 100 was the first model in Kodak’s line up of professional “Digital Camera System” SLRs, which were all based on Nikon or Canon film SLRs, with custom digital sensors and data storage devices.

The Kodak DCS 100 had a 1.3-megapixel Kodak KAF-1300 sensor, first developed in 1987 for a prototype camera built by Kodak, but later adapted to the Nikon F3. The camera was an otherwise normal Nikon F3 body, with the Kodak back and sensor integrated into a custom removable back. Unlike later cameras in the DCS series where the back was permanently attached to the camera, the DCS 100’s back could be removed and a standard Nikon F3 back could be reattached to the camera to let it shoot film again!

Connected to the back was a remote digital storage unit which was carried by the photographer with a shoulder strap. The storage unit had a 200 MB SCSCI hard drive and according to Wikipedia, could store up to 156 images without compression, or up to 600 images using a JPEG compatible compression board that was offered as an optional extra. These numbers don’t make sense to me as a 200 megabyte drive should store way more than just 600 compressed JPGs, but perhaps the technology worked differently back then.

The Kodak DCS, along with most other DCS models were aimed at photojournalists, but also proved to be appealing to ophthalmologists. It had a retail price of up to $20,000 depending on how it was configured but despite this very high price, nearly 1000 were sold, proving for the first time that digital photography was here to stay.

The longevity of the Nikon F3 makes it significant for a number of reasons. Not just how long it was made, but for it’s role as the foundation for one of the earliest digital camera platforms, as a high speed camera, and for the prestige it’s limited edition models evoked in people.

Fun Fact: A specially modified Nikon F3 was used for the mine cart chase scene in the movie Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. When filming the movie, creating a life size set with real actors would not only have been incredibly dangerous, but very large and expensive, so a scaled down version was built, and using the F3 mounted to a scale model, single frames were pieced together for a stop motion video for most of the sequence.

With the release of the Canon EOS 650 in 1987 and the Nikon F4 in 1988, the use of autofocus dominated headlines, but despite the advancements in the technology, auto focus was not good for macro or astrophotography. Even for general purpose photography, there were simply some stalwarts of the manual focus era who preferred to handle that duty themselves, which explained why so many continued to be sold for so long.

Today, there is no doubt that the Nikon F3 is one of the most historically significant cameras ever made. I would argue that apart from the original Nikon F, it was Nippon Kogaku’s second most important camera they ever made. Initial concerns about it’s electronic battery dependent shutter and use of lighter weight materials proved to be unfounded as the Nikon F3 was a rugged and reliable camera that was up to the task of regular use in harsh conditions. A large number of the Nikon F3s found today, even though in physically rough condition usually still work great, with the most common faults being the LCD display within the viewfinder.

My Thoughts

Aaah, the Nikon F3. It’s taken me nearly eight years of writing reviews to come around to this one. With a plethora of information already out there on the Nikon F3, I never thought there was much I could offer that people didn’t already know. Perhaps there still isn’t, but looking through the growing list of cameras I’ve talked about, I felt this omission was one I should correct.

The Nikon F3 in some ways was, and still is, Nikon’s most controversial camera. Certainly there was some level of controversy with other Nikon SLRs. People balked at the idea of the Nikon EM made for women and it’s plastic E-series lenses, the Nikon F4 was the company’s first auto-focus body in the professional F-series, and with the F6, Nikon ditched both the interchangeable viewfinder and manual rewind feature for the first time.

To understand the mindset of the professional photography community in 1980 when the Nikon F3 made it’s debut, it’s important to remember that as of that point, there had never been a serious contender to Nikon’s crown. Sure, Canon, Minolta, and Asahi Pentax had made “pro-spec” SLRs, but none came close to putting a dent into the dominance of the Nikon F-system. Also prior to the F3, pros weren’t used to change. The original Nikon F was in production from 1959 to 1973 and it’s replacement the F2 wasn’t a complete redesign. The F2 improved on the original F in many ways, but retained the same basic formula of it’s predecessor, and it too, was in production for a very long time.

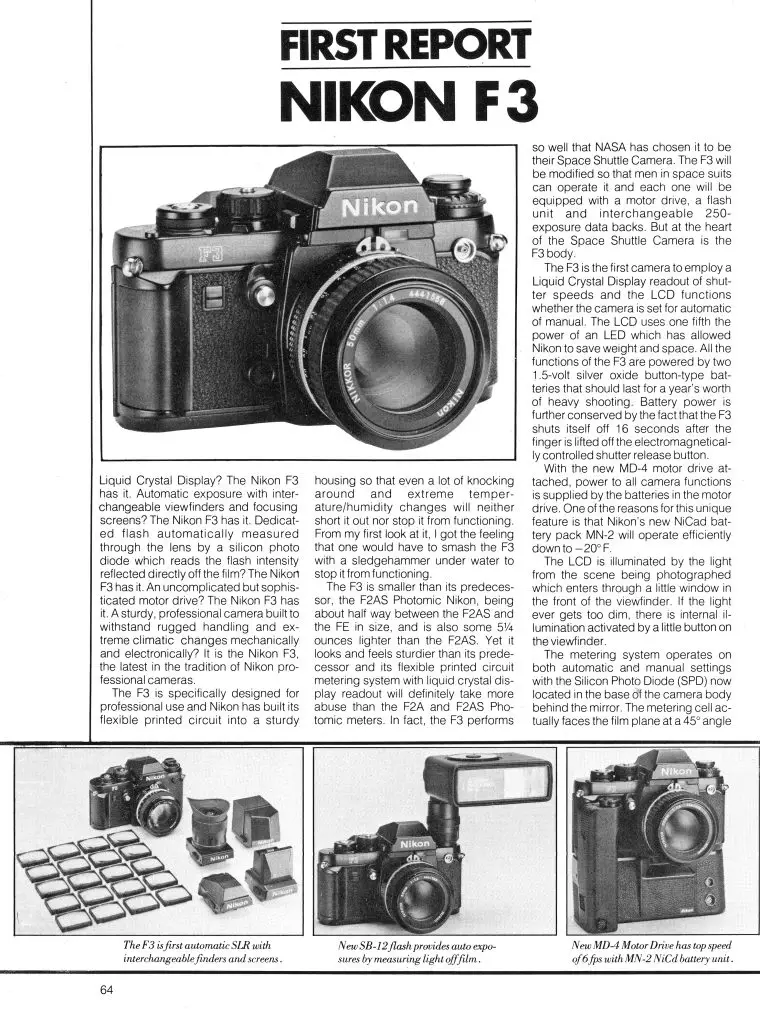

The Nikon F3 was a complete redesign. The body was smaller and was made out of more modern composite materials to reduce weight. It featured a Silicon Photo Diode meter in the body, no longer requiring the meter to be part of the viewfinder along with in-body support for Nikkor Ai lenses, a liquid crystal display in the viewfinder, and for the first time ever, had an electronically controlled shutter with aperture priority automatic exposure.

Concerns over the reliability of an electronic shutter and the dependency on batteries in a camera system known for rock solid reliability in the harshest conditions caused current users of the original F and F2 to vow that they’d never buy the F3. Sure, Nikon SLRs had electronic shutters as far back as the Nikomat/Nikkormat EL from 1972, but that wasn’t a camera designed for pros. As a result, the price of used Nikon F2s jumped considerably as people stocked up on spare mechanical F-series cameras with the fear that the F3 wouldn’t hold up to the demands of the pros.

Of course now in 2022, we have the benefit of hindsight to know that these fears were unfounded as the Nikon F3 has proven itself to be just as reliable as any Nikon that came before it. Sure, it had a few weak points, the viewfinder’s LCD being one of them, but it wasn’t anything that caused the camera not to work, and when the camera did experience a mechanical failure, it was still within the capability of most camera shops to repair.

At this point in most of my reviews, I go over the various parts of the camera, where the controls are and what they do. Since the Nikon F3 is so well known, I don’t want to spend as much time doing that, instead I’ll just cover the highlights of the camera’s controls, mentioning what was different from the F2.

Up top, the controls are typical of a professional Nikon SLR of the era. The F3 still uses a similar flash hot shoe that requires a removable adapter that connects to two metal contacts around the rewind dial. On either side of the pentaprism are two black latches that when pushed backwards allows you to remove the prism. Finally getting away from coupling pins connected to the prism, the Nikon F3 had a much easier to change viewfinder than either of it’s predecessors.

Due to the permanent location of the F3’s SPD meter in the body instead of the viewfinder, not only did this decrease the size of the prism, it also meant that the body’s shutter speed dial would always be visible, greatly simplifying it’s operation. Although both the F2 and F3 have the same top 1/2000 shutter speed, the F3 allowed you to select slow shutter speeds from 2 to 8 seconds, plus dedicated positions for a Timed shutter mode and an X-sync position. The shutter release was a bit larger than the one found on the F2 and was relocated in the middle of the film advance lever. The exposure counter was to the right and above it, a small lever to be used for intentional double exposures.

The sides, back and bottom of the Nikon F3 are pretty typical with the usual assortment of motor drive connections, battery compartment, tripod socket, and rewind buttons on the base of the camera, neck strap lugs on the side and not much to see on the back. The back of the door still has a square frame to be used with the end of a box of 35mm film to remind you what was loaded in the camera. Although companies like Fuji had already started including transparent windows to see inside of the film compartment by the time of the F3’s release, the designers must not have been ready to support that feature.

Another change to the F3 is in how the film door is opened. Unlike the F2 which still used a bottom key to open the door, the Nikon F3 eliminated support for reusable metal “Leica style” cassettes, a feature both the Nikon F and F2 had, dating back to the Nikon rangefinder era. To open the film compartment, you must first slide a black lever beneath the rewind knob to the right while lifting up on the rewind knob. This two step system for opening the back was both more modern, while still offering an extra step of security to prevent opening the camera back accidentally.

The film compartment of the Nikon F3 is very similar to that of the F2 featuring similar horizontally traveling titanium metal curtains with a vertical pattern in the curtains. Both cameras have twin polished film rails, a large and smooth black pressure plate with metal rollers to help minimize friction as film passes through the gate. The sprocket shaft is still made of metal and the door is removable via a hinge pin. The two main differences are an improved multi-slotted take up spool, and two electrical contacts below the film gate that support the use of optional data backs which were available.

Up front, the Nikon F3 is unusually crowded compared to earlier Nikon SLRs, but hinted at a generally more cluttered UI that would soon become common with SLRs. Remaining in their same locations as the F2 are the mirror lock button and lever, flash sync port, and Nikon F mount release button. The self timer is no longer a mechanical lever and is a black collar around the shutter speed dial that only offers a non variable 10 second delay. A red square LED to the left of the mirror lockup will blink to indicate the self timer is counting down.

Near where the old self timer button was, is black button with lever around it. The button operates the exposure lock for situations where you need to hold a meter reading and then recompose your image. The lever around the button operates the Nikon F3’s mechanical shutter release. Although the shutter is electrically controlled and requires power to operate at all speeds, as they did with many of their electronic cameras, Nikon wisely included a mechanical override that operates the shutter at a single 1/60 shutter speed. A lesser known feature is that the mechanical release also works with the shutter in T mode, for extra long exposures. This meant that with a dead battery, the Nikon F3 could still fire it’s shutter so that a photographer could finish their roll at a single speed if they had to.

Like all Nikon SLRs before it, the Nikon F3 supported the Nikon F-bayonet mount. Unlike the earlier F and F2, the F3 had an in-body meter and supported Nikkor Ai lenses first released in 1977. For photographers who wanted to use older non-Ai lenses, the coupling pin could be folded away by pressing a small button (not shown) near the 1 o’clock position around the lens, similar to the same feature found on the Nikon EL2, FM, and FE.

Perhaps the most significant change to the front of the Nikon F3 is the addition of a small finger grip for the photographer’s right hand. Although much smaller than the very deep hand grips that would become common on SLRs in the next decade, having a place to rest your fingers without having to maintain inward pressure on your hand is a huge improvement over cameras without one. Adding to the tactile improvements is that on the F3, this grip is covered in what appears to be some type of synthetic leather that is very smooth, and even on my 42 year old example, is still soft and supple, increasing grip. Whatever material this is made of seems to have held up remarkably well as most Nikon F3s I see out there have the original covering still in tact.

The Nikon F’s viewfinder has almost exactly 100% coverage which for the professional photographer was a big deal as you can see exactly everything that will be captured on film without the typical 5-10% crop of most SLRs. Viewfinder magnification is 0.8% which shrinks objects somewhat, but is well within what photographers expected. Like the F and F2, the focusing screen is interchangeable with one of 15 different screens. The one on this camera is the Type K screen with split image focus aide in the center, surrounded by a microprism collar and 12mm reference circle completely surrounded by a matte Fresnel screen. The viewfinder is extremely bright and easy to focus. Although there were a great many other screens available, I would guess that an overwhelming majority of F3s kept this screen.

Above the viewfinder screen is a small rectangular LCD window and square “Judas window” which optically displays the selected f/stop directly from the ring on the lens (non-Ai Nikkor lenses won’t show anything). The LCD screen displays either the shutter speed chosen by the meter in Auto mode, or in manual mode, the chosen speed along with the letter M and above it either a + or – symbol to indicate over or under exposure. Although this system works fine, and gives the photographer the necessary information to make a properly exposed image, by the time of the Nikon F3’s release, nearly every other Japanese SLR maker was experimenting with full information displays. The shutter speed readout at the top of the viewfinder window is a bit inconvenient as well. Perhaps it’s my familiarity with later SLRs where that info is at the bottom, but I could never get used to it on the F3, ignoring it for most of the time I’ve shot with this camera.

Overall, the design of the Nikon F3 is very good. The ergonomics of the smaller body with finger grip make holding the camera a lot more comfortable than the F2, especially during long shooting sessions. The camera’s most important controls are all logically located and easy to reach. Although a good number of things aren’t quite as obvious and require a refresher with the manual, these are the features you’re less likely to need every day.

A huge number of these cameras were sold over two decades of the camera’s production, and millions more photos were taken with them. You don’t need me to tell you what kinds of great images you can get out of one, but if you keep reading, I’ll do it anyway!

Repairs

The Nikon F3 is far too advanced for me to consider taking it apart and attempting a repair. If you were to come across one that isn’t working correctly, this is a camera you definitely should send off for a proper CLA.

The Nikon F3 is far too advanced for me to consider taking it apart and attempting a repair. If you were to come across one that isn’t working correctly, this is a camera you definitely should send off for a proper CLA.

However, I did identify a trick for getting a stuck shutter working again. When this Nikon F3 came to me, it was in non working condition. Putting in new batteries would get the LCD to light up, but the shutter wouldn’t fire at any speed. As I played with the camera, I noticed that if I put the shutter into T mode, and activated the mechanical shutter release on the front of the body, the shutter would fire. After doing this, I put it back into one of the many electronic modes and the camera resumed normal operation.

I have no idea if this is repeatable on other cameras, but it doesn’t hurt to try. Before giving up on an F3 whose shutter appears to be inoperable, try this and see if it helps!

My Results

I was pretty excited to finally shoot the F3 as I already knew what to expect from the original F and F2, but something I knew would be an issue when the time came to write this review, is that it really doesn’t matter what Nikon body you use, if you mount a Nikkor F-mount lens to it, it’s not going to look any different than if that same lens was mounted to another body.

While it would have been easy enough to mount some 50mm f/1.4, f/1.8, or f/2 lens to it, I would have gotten pretty run of the mill, but excellent, photos. Sure, I have a couple versions of 28mm and 35mm Nikkors, I also have an 85mm f/2 and the wonderful 105mm f/2.5 plus a few others, but I wanted to try something different.

Thankfully, I got my wish when browsing through a local resale shop and I came across a Nikon FG with a lens I had never seen, the Nikkor 20mm f/4. What strikes me the most about this lens is how small it is. Externally it has almost the same dimensions as the 50mm f/1.8 and on the scale, they’re almost identical too. Of course the f/4 maximum aperture is pretty slow, but it is a Nikkor though, so how bad could it be? For my first two rolls through the F2, I used the 20mm f/4. I shot a roll of Tmax 100 and Kodak ColorPlus 200 so see how it performed on both. I left the camera in aperture priority mode the entire time.

As I suggested above, the results in the gallery are more about the lens than the camera, but that’s not to say the camera doesn’t play a role too. There is something to be said about a well designed camera that does everything it is supposed to, but doesn’t get in the way of what you need to do, which is make beautiful pictures. Although the F3 has a great number of controls, many of which aren’t exactly intuitive, when it comes to loading in some film and making pictures, it doesn’t get in the way.

The camera has a reassuring feel and heft and nearly perfect ergonomics. With a smaller and lighter body, the F3 is easier and more comfortable to hold, and you’ll appreciate it’s lighter weight body, it will cause you less fatigue. The viewfinder is great, the auto exposure system works perfectly, and it supports nearly every Ai and non-Ai Nikkor lens ever made.

There is a lot to love about the Nikon F3, but not everything. My least favorite part of the camera is also something that has proven to be the camera’s biggest weakness, which is the viewfinder LCD, or more specifically, the location of the LCD. While it is not unusual to see Judas windows that display selected f/stops above the viewfinder, that Nippon Kogaku chose this location for the camera’s LCD seems odd. Perhaps it’s conditioning from countless other SLRs before and after, but I am far more used to seeing shutter speeds below the viewfinder. To have to angle my eyes up to see the chosen shutter speed feels unnatural to me, and results in me almost never looking at it. I find that seeing the LCD is even worse with the High Eyepoint (HP) finder, as the viewfinder image is so big, it partially blocks being able to see the display unless you angle your eye at just the right position. Complaints about the location of the LCD seems to be shared by other non-fans of the Nikon F3, citing it as one of their least favorite aspects as well.

In addition to not loving the location, the LCD has not aged well, with many examples of the F3 having a screen that has bled, or completely faded away. This example, although the LCD was still functional, was difficult to read in bright light as the contrast from the liquid crystals has faded over the years.

One very minor nitpick is that for such a world class camera, it seems Nippon Kogaku went out of their way to hide certain functions of the camera. Most significantly is the power switch, which is an unlabeled collar around the shutter release and wind lever. The self timer is hidden as well, once again as an unlabeled collar around the shutter speed dial. Would it have been so hard to label these some way? I would be willing to bed, most pro photographers never gave a thought to the location of a power switch or self-timer, but having handled and shot so many different cameras, it just seems weird that the locations for these controls are not obvious on such a popular camera.

As this review approaches 8000 words, is there really anything I can say about the Nikon F3 that hasn’t been said a million times by a million people over the past 40 years? Probably not. But still, the merits of this camera are still debated to this day. I often hear people ask, “What is the best Nikon I should buy”, or they debate whether they should get an Nikon F, F2, or F3. While there are certainly good reasons to buy other Nikon SLRs, none of those reasons are because this isn’t a good camera.

If you appreciate a solid and well built manual focus SLR with interchangeable viewfinders, support for the largest amount of Nikkor lenses, excellent ergonomics, and a body that isn’t as intrusive to hold as Nippon Kogaku’s earlier pro-level SLRs, then this might just be the “best Nikon SLR”!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Nikon_F3

https://imaging.nikon.com/history/chronicle/history-f3/

https://photothinking.com/2020-03-07-nikon-f3-legend-with-a-red-stripe/

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2015/11/02/ccr-review-24-nikon-f3/

https://casualphotophile.com/2016/04/10/nikon-f3-camera-review/

https://www.kenrockwell.com/nikon/f3.htm

https://thedrunkweddingphotographer.com/summerimperfect/nikonf3

This article covers a lot of territory. The success of the Nikon F series was partly due to Leica prices going up, and the emergence of SLR competitors to the Nikon F series was because Nikon prices were considered too high. The competitors also brought some important innovations to the table. Personally, I switched over to the Olympus OM series at the time. And the Canon AE-1 was making a big splash, as everyone was trying to decide on Auto-shutter vs. Auto-aperture exposure modes.

I recall learning that Nikon built the F3 shutter for a service life of 200,000 actuations. The “parts & repair” F3s I’ve come across have had perfect shutters … cannot say the same for the electronics. Still prefer tp take the F2 when I go into the outback!