This is a Rokuoh-sha Pearlette, a compact folding camera in the “Vest Pocket” style, made by Rokuoh-sha which was part of Konishiroku, predecessor of Konica. It was built in Yodobashi, Tokyo, Japan between the years 1925 to about 1947. The Pearlette has an all metal body and folds using double scissor struts and takes 4 cm x 6.5 cm images on 127 format roll film. The Pearlette’s design and features evolved many times throughout it’s production run, but the name never changed, nor was there any attempt to uniquely identify each variant, so it can be difficult to identify which specific variant each camera is, but this particular example is almost certainly a 1940 model. The Pearlettes were very nice examples of pre-war Japanese cameras, with simple, but reliable lenses and shutters. They are historically significant as the first mass produced Japanese camera and one of the first Japanese cameras built to use roll film instead of dry plates.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (eight 4 cm x 6.5 cm exposures per roll or sixteen 3 cm x 4 cm with mask)

Lens: Unknown focal length (probably 7.5 cm) US 8 Meniscus Achromat uncoated 2-elements in 1-group

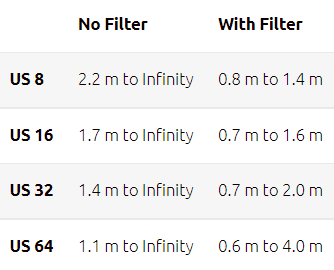

Focus: Fixed Focus, 1.1 meters (at minimum aperture) to Infinity, with Close-Up Attachment, 0.6 meters to 4 meters (at minimum aperture)

Viewfinder: Folding Reflex or Wire Frame Finders

Shutter: Echo Rokuoh-sha Metal Blade

Speeds: Single Speed, ~1/50 second

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Other Features: None

Weight: 402 grams

Manual (in Japanese): https://mikeeckman.com/media/KonishirokuPearletteManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Rokuoh-sha Pearlette is a historically significant camera for a variety of reasons, but more so than that, is an extremely fun and attractive camera that delivers excellent results from it’s simple doublet lens. Although only slightly larger than the Kodak Vest Pocket which shoots the same size images on the same kind of film, the Pearlette improves upon the Kodak’s ergonomics and operation delivering great images. This was the camera that helped launch the Japanese photo industry and is a fun and fascinating camera to both use and have in any collection. Highly recommended! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an unusually capable camera with a simple lens and simple operation, the complete package | ||||||

| Final Score | 13.6 | ||||||

History

Note: The historical information I use in a majority of the reviews I write on this site is sourced from many different locations such as first hand accounts from experts, published camera history books, 20th century photographic magazines, and in some cases, reputable websites. I try to cite sources where I can for the information I find.

For this review, a majority of the historical information comes from a single source, the book “The History of the Japanese Camera” by John Baird, published by Historical Camera Publications in 1990.

The next several paragraphs are a highly condensed version of the first six chapters of that book, written in my own words. I did not copy and paste or plagiarize anything from that book, rather, I made an attempt to tell the early history of the Japanese camera industry and how it pertains to Konica, and the versions of the company that existed prior.

John Baird’s book is long out of print, but if you have a chance to check it out, the full story is extremely rich and fascinating, and one I recommend reading.

To understand the history of Konishiroku and how the company eventually became Konica, we must first understand the history of the entire Japanese optics industry. The earliest known evidence of optical production in Japan goes back to 1549 when the Dutch explorer St. Francis Xavier brought the a simple microscope and telescope to Japan.

This exposure to the study of optics led to an early glass making industry in the 1570s. Japan, at the time was a very isolated island and over the course of the next several hundred of years, Japanese artisans learned the ways of producing glass for food storage and plate glass for windows.

At the time, Japan lacked the knowledge, resource, nor the technology to advance glass making beyond simple items, the least of which would be useful for optical glass needed for eyeglasses or scopes. What little existed in Japan at the time was all sourced trough trade with Dutch and other European countries, and eventually, the United States.

The earliest known photographic apparatus in Japan was brought to the company through a merchant in 1841 and brought to Lord Shimazu Narioka of Kagoshima. It was an early wooden daguerreotype similar to those being used in Europe by Louis Daguerre and others.

At the time, the Japanese people were highly superstitious, and it was believed that in order for an image to be made of a person, their soul would need to be taken from the body to appear in the photograph. The name given to the first cameras were “hitome maho no kikai” which loosely translates to “the devil’s trick machine”. Nevertheless, Lord Narioka was fascinated by the device and eventually convinced his son, Prince Nariokira to pose for a photograph. This photo, taken in June 1841 is believed to be the first ever portrait made in Japan.

Realizing that the prince’s soul was safe, the idea that a camera could be a useful tool spread, and soon, importers all over Japan were sourcing photographic goods from European traders. In 1857, the first wet plate cameras made their way over from Europe and photographic studios started to become common in metropolitan areas. In the early 1870s, after the start of the Meiji Restoration, a wider acceptance of Western ideologies and technologies, along with the decrease in earlier superstitions caused photography to become immensely popular in Japan.

This new found popularity led to a shortage of imported cameras as they simply could not be brought to the island nation fast enough. This in turn, resulted in the creation of small shops who began to copy European dry and wet plate cameras, producing the first ever Japanese built cameras. Prior to the 1870s, photographic goods were sourced from importers who deal in a variety of goods, but weren’t dedicated to photography.

This new found popularity led to a shortage of imported cameras as they simply could not be brought to the island nation fast enough. This in turn, resulted in the creation of small shops who began to copy European dry and wet plate cameras, producing the first ever Japanese built cameras. Prior to the 1870s, photographic goods were sourced from importers who deal in a variety of goods, but weren’t dedicated to photography.

In 1871, the first Japanese owned photographic importer was setup in Tokyo by a man named Tokichi Asanuma. Asanuma came from a family of chemists who dealt largely in pharmaceutical goods, which prepared them for the manufacture of photo sensitive chemicals and other photographic products.

Two years later, in 1873, a competitor to Asanuma’s business was formed by Rokusaburo Sugiura. Sugiura was the son of pharmacy dealer and created a new import business as a branch of his father’s business, Konishi-ya Rokubei Ten. Together, both Asanuma and Suigara’s businesses laid the foundation for a new photographic industry in Japan. Imports of cameras, lenses, chemicals, and other supplies were exclusively handled by both shops, and they quickly became leaders in the industry. In 1876, Sugiura would reorganize and rename the company to Honten Konishi Rokuemon, or simply Konishi Honten for short, and it would become the largest Japanese owned photographic merchant.

These early imported cameras used a wet plate process, but in 1881, dry plate photography was introduced to Japan, and it allowed cameras to become more portable so that they could be used away from the studio, it further opened Japan to the world of photography. Although the industry was expanding, the cost to bring cameras and other goods on the long journey from Europe was very high, meaning that photography was only enjoyed by those who could afford it.

Dry plates would dominate Japanese photography until the early 20th century. Although roll film and other photographic films would gain popularity in Europe and the United States around this time, these early film stocks were not good at surviving the long journey across land or sea to Japan, and once there, Japan’s very high humidity prevented film from catching on until much later.

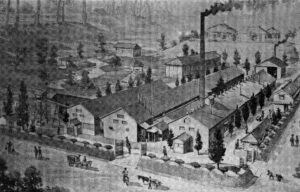

In 1882, Konishi Honten would setup a new factory to build photographic chemicals and cameras. Still a burgeoning industry, the earliest Japanese cameras were simple box cameras, but eventually large format plate cameras would become the dominant type. In 1895, Konishi Honten was producing at least sixteen different models all copies of European designs.

Konishi Honten and other early Japanese camera makers struggled to sell their cameras in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, not because they they weren’t any good, in fact, around the turn of the 20th century, Japanese built copies of European cameras were just as good as the originals, however the Japanese culture put tremendous value on imported goods, so the domestic copies were seen as inferior and in low demand. In order for a Japanese camera maker to compete, he had to sell his products at a steep discount, even though they were just as good. Of the Japanese cameras that were sold, most had European lenses such as Ross Dallmeyer and Steinheil lenses. By the first decade of the 20th century Cooke Anastigmats and Zeiss Tessars became common. It would not be until the 1930s when large numbers of Japanese made cameras became common.

On May 5, 1902, Konishi Honten, still largely an importer who also made some of it’s own products, established a new division called Rokuosha (often stylized as Rokuoh-sha) in Yodobashi, Tokyo to mass produce it’s own brand of photographic plates and printing paper. In September 1903, Rokuosha would produce what would become Japan’s first mass produced camera, called the Cherry Portable Hand Camera. In addition to the Cherry being mass produced, it was also the first Japanese camera made for the amateur and the first to ever be given a model name.

The Cherry was a simple camera, resembling an early box camera. It had a single speed rotary shutter with both an Instant and Bulb setting and used a single element meniscus lens with a fixed aperture and fixed focus. The lens itself was almost certainly imported from a European lens maker as at the time the Japanese optic industry did not have the technology to produce quality optical glass in any large amounts. The Cherry used a drop plate mechanism that allowed the photographer to make up to 12 prints before having to return to a dark room to unload the camera. It produced 2 ¼ x 3 ¼ inch images on dry plates, but a later model produced larger 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ images. Since photographic enlargements were not common in Japan at this time, the larger images proved to be more popular as the finished plate could be reversed to make a 1:1 contact print.

The Cherry proved to be immensely popular and prompted the creation of other competing designs by other manufacturers. In 1906, Rokuosha would produce the Sakura Pocket Prano, it’s first in the “hand camera” design, a compact folding camera that made 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ inch images like the larger Cherry model. Simple box, and folding hand camera dry plate design remained popular until the 1920s, at which point some brands of photographic roll film started to trickle in from importers. Newer films were more stable than the emulsions from the late 19th century and could survive the long trip to Japan. The first domestic roll film was produced in 1928 by Asahi Shashin Kogyo, and a year later Rokuosha followed with their Sakura orthochromatic black and white roll film.

Fun Facts: Early Rokuoh-sha cameras often featured the character “六” which stands for ‘roku’ or ‘six’ inside of a Cherry Blossom. The Cherry Blossom or ‘Sakura’ is featured prominently in many Japanese traditions. Sakura is a symbolic flower of spring, and stands for life, birth, renewal, and beauty. The number six is a reference to Konishiroku’s founder, Sugiura Rokuemon VI and was used in the name of Rokuoh-Sha, and later, in Hexar and Hexanon lenses as the “hex-” prefix also stands for the number 6. In the late 1920s, Sakura would be the brand name of Konishiroku’s line of photographic film,

Fun Facts: Early Rokuoh-sha cameras often featured the character “六” which stands for ‘roku’ or ‘six’ inside of a Cherry Blossom. The Cherry Blossom or ‘Sakura’ is featured prominently in many Japanese traditions. Sakura is a symbolic flower of spring, and stands for life, birth, renewal, and beauty. The number six is a reference to Konishiroku’s founder, Sugiura Rokuemon VI and was used in the name of Rokuoh-Sha, and later, in Hexar and Hexanon lenses as the “hex-” prefix also stands for the number 6. In the late 1920s, Sakura would be the brand name of Konishiroku’s line of photographic film,

In the 1920s, with an increase of popularity in roll film, some models were created that supported both roll film and dry plates. A popular size was 6 cm x 9 cm which was very close to the popular 6.5 cm x 9 cm dry plate making conversion between dry plates and film easy.

In 1921, Konishi Honten would be renamed to G.K. Konishiroku Honten, but would continue to manufacture cameras and other photographic accessories using the Rokuosha name. In 1925 came the release of a new camera called the Pearlette which was the first Japanese camera to exclusively use roll film. It is a close, but not identical copy to a German camera called the Picolette, which was first manufactured by Nettel Camerawerk in 1914. In 1919, Nettel would become Contessa-Nettel, and in 1926 would merge with three other German companies to become Zeiss-Ikon. The Picolette was produced under all three company’s names, before eventually being discontinued around 1930.

The original version of the Pearlette very closely matched the design of the Picolette, retaining it’s side loading design that used a removable film carrier and simple wire frame finder, but later versions updated the design with a hinged back, removable film plane, dual film formats, and a close-up filter, all features not available on the original Picolette. If you were to compare a later Pearlette with an early Picolette, the cameras would be very different, but they did not start out that way.

The Pearlette used type 127 roll film, which at the time was more commonly called “Vest Pocket Film” because of that style of film’s origination with the Kodak Vest Pocket in 1912. It was not only the first mass produced Japanese camera to only use roll film, but it was one of the first made exclusively of metal without any use of wood.

Like the Picolette that it was based on, the Pearlette proved to be a popular camera that was in production for a long time and came with a variety of lens and shutter combinations and was revised multiple times before finally ending production around 1949. Rokuoh-sha made no attempt to uniquely identify each version of the Pearlette with a different model number, so collectors tend to identify each model by the year it first became available. The Pearlette page on camera-wiki does an excellent job of thoroughly explaining all of the different variants of the Pearlette which I won’t retype here, but if you’d like to know more, check out their page for a lot more information. If you’d just like a summary, here is my attempt at a condensed version.

- 1925 – Side loading, film advance key, no wireframe finder, collapsible brilliant viewfinder, “Pearlette” engraving on the side of the camera, 4×6.5 images only, removable disc on the back for cleaning the lens and attaching to an enlarger, scissor struts further extend for close-ups, Woco Wollensak shutter, T setting on shutter, Wollensak Deltas Aplanat lens

- 1928 – Same as above, except revised Woco shutter with B setting instead of T, revised shutter release lever with one-piece attached cable release socket, slightly larger Pearlette logo on the side

The 1929 Pearlette had a revised body and was the first model with a close-up lens in the finder. - 1929 – Revised body that was larger than before, addition of wire frame finder with close up lens in the middle, scissor struts no longer extend to a second position for close-ups, retractable rear eyepiece for wireframe finder is build into rear exposure door, non-collapsing rigid brilliant finder, revised shutter release still with cable release socket but is now a separate piece, various rivets from the earlier versions are replaced with screws

In 1931, Pearlettes started to have an ornate floral pattern on the sides. Image courtesy, Jacques Bratieres, flickr. - 1931 – Revised wire frame that was both more rigid and removable, distinct floral pattern on both sides of the camera, and Pearlette logo was changed once again, various parts of the camera were made with a lighter allow metal, reducing the weight of the camera

- 1932 – No longer uses Wollensak lenses and shutters, shutter is a Rokuoh-sha Pegasus and lens is either a Meniscus Achromat (rumored to have been made by Asahi Kogaku) or Hexar Ser.11 f/6.3 lens, orange filter added to wireframe viewfinder

- 1933 – Film compartment switches to a hinged rather than side loading design, film advance key replaced with a metal knob, dual format capable of both 4.5cm x 6cm images and 3cm x 4cm images via a removable film plate that doubles as a mask, three exposure windows on the back of the camera for both formats, revised rear eyepiece that has a rectangle for framing 3×4 images, revised floral pattern on the sides, same shutter as 1932 and Meniscus Achromat lens but Hexar f/6.3 lens replaced with Zion f/6.3 lens

-

A big change occured in 1933 switching from side to back loading with a hinged door. Image courtesy, Dirk HR Spennemann, flickr. 1933 Variations – Some versions of the 1933 model renamed the Pegasus shutter to Echo but otherwise is identical, a version with maroon body and bellows exist sometimes called the Color Pearlette, Zion f/6.3 lens renamed to Optor f/6.3, some versions have a depth of field scale on the back of the shutter, changes to the location of the film rollers in the film compartment

- 1935 – Revised front plate with black crackled paint instead of crinkle paint of earlier versions, revised front Pearlette logo, changes to wireframe finder attached to the body with two screws instead of one, advance knob made of black Bakelite instead of metal, white arrow painted on advance knob, film pressure plate is revised adding a “tunnel” that the film must pass through for proper transport

- 1937 – New finish with nickel plating on the edges, black crackled paint on the sides replaces the floral pattern of earlier models, cosmetic changes to Echo shutter with curved stripes on opposite sides of the lens, Optor lens rim is nickel plated instead of painted black

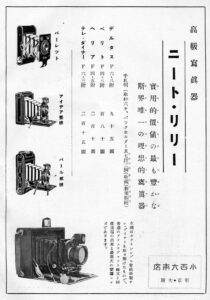

- Luxury Pearlette – An upgraded version of the 1937 camera with a front-cell focusing Optar or Hexar f/4.5 lens (this is the only version of the camera with a focusing lens), some versions have the same black crackled paint but others have a leather covering, rigid brilliant finder is replaced by a folding optical finder on the side of the camera, rear exposure windows are changed with rectangular windows covered by a sliding cover, depth of field scale riveted to the back, other cosmetic changes

- 1940 – Front Pearlette logo is no longer engraved into the front plate, but is a separate plate riveted to the camera below the lens, Rokuoh-sha logo no longer appears on the front of the camera, no depth of field scale, some versions of the camera have nickel and others chrome plating possibly as a result of supply issues due to WWII, production halted in May 1941

-

Not all postwar Pearlettes say “Made in Occupied Japan” but all that do are postwar models. 1946 – The first postwar models resumed made up almost entirely of left over parts from 1940 and earlier versions, some have a plate inscribed with “Made in Occupied Japan” but not all have this plate, revised Pearlette logo on front with a thin chrome frame around it

- Other Postwar Variants – Many versions of the postwar cameras were made with left over parts from earlier cameras, some with features dating back to 1935 making them difficult to date, a reference as late as December 1949 suggests a version with a f/4.5 Hexar was available, possibly suggesting a re-release of the Luxury Pearlette, but none have ever been found

All signs point to the Pearlette ending production in 1949. There are no records of total production of cameras, but it is estimated that around 10,000 were produced between 1946 and 1947. Whatever the total number is, the camera’s long production from 1925 to 1949 and the vast number of them for sale today, suggest a good number was produced.

It is safe to assume that prewar models were produced exclusively for the domestic Japanese market, but it is plausible that some postwar models were sold for export, although it is not clear how much demand there would be in the late 1940s from Western photographers wanting to buy a Japanese copy of a German camera which dates back to 1914.

Prices for the prewar models range from ¥17 for the earlier models with the basic lens to ¥28 for models with the faster f/6.3 lenses. The Luxury Pearlettes were advertised for ¥45 as late as 1941. Inflation dramatically changed the Japanese yen after the war, and prices fluctuated wildly from as little as ¥635 in early 1946 into the thousands of yen by 1949 making getting an accurate 21st century analogy impossible.

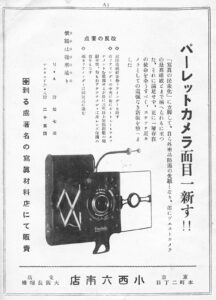

The success of the Pearlette inspired another Japanese company called Fuji Kōgaku to make their own copy. Fuji Kōgaku was not the same company as Fuji Shashin Film K.K. who would later become the FujiFilm corporation we know today, but rather a short lived camera and lens mater that was most active from 1936 to 1944 and possibly shortly after the war.

In 1936, Fuji Kōgaku would produce two cameras with the name Dianette and Pionette which were very similar to the Pearlette. Both cameras were the same to each other, but the difference in names appears to be due to who distributed the camera. The Dianette appears in ads for the Japanese distributor Yamamoto Shashinki-ten, and Pionette was distributed by Fuji Kōgaku themselves.

Compared to the Pearlette, the two cameras were most similar to the 1933 and later Pearlettes offering a hinged film back, both 4.5×6 and 3×4 formats, and wire frame finder. Lenses available for the cameras ranged from f/4.5 to f/8 designs, although there was a focusing f/6.3 lens that was not available on the Pearlette. Earlier Dianette and Pionette cameras shared the same curved “kickstand” below the lens for supporting the camera on a flat surface, but later switched to a simpler folding kickstand that was likely cheaper to make. The prices for the cameras matched that of the Pearlette, ranging from ¥17 to ¥38 depending on configuration.

Two additional cameras were made by Rokuoh-Sha using the Pearlette name, but neither are related to the original. The first was a folding bellows camera called the Special Pearlette and was made in 1929. It is a copy of the Goerz Rollfilm Tenax and features an almost identical design. In that camera’s page on camera-wiki, it suggests that perhaps the cameras were made up of parts made by Goerz and assembled by Rokuoh-Sha.

That the Special Pearlette may have been of German construction is supported that the lenses were all Rodenstock designs and the shutters were either Prontor, Ibsor, or Compur models. Apart from a plate engraved with “Rokuoh-Sha” beneath the lens and the name “Special Pearlette” embossed into the leather, there is little to suggest this was a Japanese camera.

One final camera in the Pearlette family was a lower end model called the Pearlette B (some sites say B. Pearlette) which was also made by Rokuoh-sha and shared the Pearlette name, but was a completely unrelated camera with a self-erecting folding bed design. Like the original Pearlette, the B model shot both 3cm x 4cm and 4cm x 6.5cm images on 127 roll film, but had a simple metal frame viewfinder and a single element meniscus lens with an approximate maximum aperture of f/16. The Pearlette B only appeared in advertisements in late 1935 with a price of ¥9.50.

In the years after World War II, Japanese optics companies would revolutionize the industry. Originally small brands that western photographers had never heard of, soon brands like Nikon, Canon, Konica, and Minolta would become internationally recognize names that everyone could respect.

While it’s not fair to give all that credit to one model, or even one company, the role that the Pearlette played was a critical one, and definitely deserves to be included in that history. It would be impossible to mention the number of photographers, engineers, and other technicians might not have taken up their careers had it not been for what was at the time the most successful Japanese camera ever made.

For that reason, the Pearlette demands to be included in any camera collection. Whether you just want it for it’s historical significance, or if you just like old Japanese cameras, the vast number of varieties of this one model is worthy of notice too. Earlier models are very different from their later ones, and with fast lenses like the f/4.5 Hexar and rare variants like the Luxury Pearlette, there’s likely a model for everyone. My collection starts with just this one, but something tells me it won’t be the last!

My Thoughts

Last year, I had a revelation that of all the cameras I owned, I had a shockingly low number of pre-war Japanese cameras. Certainly there were a lot more from after the war, but aside from an early first generation Minolta TLR, I had nothing else in my collection from before 1942, so I sought out models to try and own and possibly review.

As fate would have it, I would bid on an auction of old folding cameras and in it was a blurry black camera that somewhat resembled a Kodak Vest Pocket camera. There was enough that I could identify in the rest of the lot so I took a chance and won. When the box arrived, I sought out that mystery black camera and it turned out to be this Rokuoh-sha Pearlette. The camera was in excellent physical condition, excepting the bellows clearly had seen better days and were most likely no longer light tight. The body was made from solid metal and the black crinkle paint all over the body was attractive and added a bit of glass to the finish.

When I suspected it might be a Kodak Vest Pocket or something similar, I wasn’t far off as the overall size and weight of the body are pretty similar. Both cameras use a similar double scissor folding mechanism with the front lens and shutter always exposed, and both use the same 127 “Vest Pocket” film. When held side by side, the Kodak is smaller, however when you see the Pearlette by itself, it will definitely remind you of the Kodak.

With the camera erected and sitting on a flat surface using the large kickstand that is built into the front plate, the top edge of the body has a nickel plated film door release latch. Slide it to the left and the film compartment swings open. On this side of the shutter plate are the folding reflex viewfinder and shutter release with cable release socket to the side. The Echo shutter on the Pearlette is a self cocking design, so each press of the shutter release will always cause the shutter to fire.

Between the two sides and bottom of the camera, there’s not much to see other than the film advance knob and 1/4″ tripod socket on the side of the camera to the right when looking at the film door release latch. This copy had some kind of 1/4″ tripod extension screwed into the body’s tripod socket, perhaps to make it easier to mount on a tripod. This appears to be an aftermarket accessory however, and not original to the camera.

On the side of the camera opposite of the door release latch, suspended by a metal frame connected to the folding struts is a second 1/4″ tripod socket which would be used with the camera in portrait orientation.

Around back, the camera has a total of three different red exposure peep holes. One in the center is hidden by a sliding rear eyepiece for the wire frame finder that can only be seen when the finder is pulled into it’s up position. Later models of the Pearlette like this one were dual format, allowing you to shoot both 4 cm x 6.5 cm “full frame” images along with 4 cm x 3 cm “half frame” images via a mask that is inserted into the film compartment.

When using the half frame mask, you use two red windows which are also hidden by a door that is opened when moving a separate slider from the number 1 to the number 2. It sounds a bit confusing, but in practice, it works like every other 3 cm x 4 cm 127 camera in which you have to use the same exposure numbers for two frames. The first exposure is when the number 1 on the backing paper is seen through the first window, the second exposure is when the number 1 is seen through the second window, the third when the number 2 is seen through the first window, and so on until the 16th and final exposure is made when the number 8 is seen through the second window.

Opening the film compartment, the hinge is on the same side of the camera as the kickstand. Orienting the camera with the hinge on the right, film transports from right to left, onto removable 127 film spools. Loading film into the Pearlette is almost like any other roll film camera in that you need to move an empty spool to the take up side, and then install a new spool on the supply side and attach the paper leader into a slot in the spool.

Where the Pearlette differs from most roll film cameras is that the camera has a removable pressure plate which also doubles as the frame mask. In this example, I only have the 4 cm x 6.5 cm mask, but when the camera was new, it would have had a second mask for the smaller exposures. Regardless of which size you want to shoot, you must have one of the two masks in the camera as loading film into the camera without either mask means there is no pressure plate and the film will not lay flat across the film gate, which will result in badly out of focus images. With the pressure plate in place, you must feed the paper leader through a slot on the side of the pressure plate to the other side. I found that it’s a bit easier to do if you first remove the pressure plate, thread the paper leader through it, then put the pressure plate back into the camera and finish loading the paper leader onto the take up spool. It’s certainly not typical of a roll film camera, but only adds a few seconds to the process of loading film. A sticker with Japanese lettering printed on the pressure plate probably gives instructions on how this works, but was partially torn on mine, so I could not read it.

Up front, the Pearlette differs from the Vest Pocket Kodak, in that the entire leaf shutter, including the shutter speed ring around it’s perimeter is fully exposed. Changing shutter speeds from 1/25 to 1/200 plus Bulb is done by moving a small slider around the outer edge of the ring, and aperture settings using a similar slider on the opposite side of the camera.

The Pearlette’s Meniscus Achromat lens was not measured using standard f/stops, but rather in the Universal Standard or US scale. Use of the US scale predates the f/stop system as it was first developed in the 1890s, but quickly fell out of favor in the early 20th century. It is unusual for a camera made as late as 1940 to still use it, and even more strange, only base level Pearlettes with the Achromat Meniscus lenses had it. Models with better lenses used regular f/stops.

When using the US scale, US 8 is equal to f/11, 16 is equal to f/16 and 32 is equal to f/22 and 64 is equal to f/32. Cameras using the US scale were much more common in the late and very early 20th centuries before the common f/stop scale was used.

Another interesting feature of the Pearlette is the swing out wire frame finder, which also doubles as a close-focus filter. Whether you want to use the wire frame finder or not, you must fold it out while shooting group photos or landscapes as when it is shut, the close-focus filter changes the focus range of the lens. With the close-focus filter in place, a smaller yellow filter covers the eyepiece to serve as a reminder that the close-focus filter is in place. The focus range of the camera with or without the close-focus filter depends on what your aperture is set to. I have reproduced the focus distances from the Pearlette’s manual with and without the filter in place at various apertures in the chart to the right.

Another interesting feature of the Pearlette is the swing out wire frame finder, which also doubles as a close-focus filter. Whether you want to use the wire frame finder or not, you must fold it out while shooting group photos or landscapes as when it is shut, the close-focus filter changes the focus range of the lens. With the close-focus filter in place, a smaller yellow filter covers the eyepiece to serve as a reminder that the close-focus filter is in place. The focus range of the camera with or without the close-focus filter depends on what your aperture is set to. I have reproduced the focus distances from the Pearlette’s manual with and without the filter in place at various apertures in the chart to the right.

The Pearlette has two viewfinders, the first, and the most common is the folding reflex finder next to the shutter release. If you’ve ever handled any kind of folding American or German camera from the early 20th century, you’ve seen these with their “plus sign” shaped window which allows you to compose your image for both portrait and landscape shots. Parallax is pretty severe, but back then, no one really thought about focusing close-up. These viewfinders are just for approximation.

And while they’re good at approximation, they’re still slow in operation as holding the camera at waist level and squinting through the tiny opening is often a challenge. For situations in which you need to frame fast action shots, you can use the wireframe finder. To use it, first make sure it is folded up and the rear eyepiece is in the up position, then looking through the small circle in the eyepiece, get your eye as close to you can until the circle framing the filter has the same perspective as what you see through the small circle. When the filter circle and eyepiece circle look the same, everything within the wire frame will be captured…at least in theory.

One final detail on the base level Pearlette is that the front of the shutter has some kind of black plastic hood screwed into it. This hood is not further threaded to accept filters, and apart from possibly protecting the exposed metal diaphragm blades behind it, does not seem to serve any other purpose. You can unscrew it from the shutter and still use the camera as normal. I made my best attempt at Google Translating the Pearlette’s Japanese language user manual and could not find a description of what this is used for so if someone knows, please let me know in the comments below.

The Pearlette is both a simple camera, but one that a lot of thought was put into it. It was based off a successful Zeiss-Ikon camera and improved upon that model by adding several new features. Although the lens on this particular example was the lowest spec one available, Rokuoh-sha, and later Konishiroku, and later Konica, were well regarded as excellent lens makers, so it stands to reason this combination might punch above it’s weight. But does it? Keep reading…

Repairs

Although the shutter and lens on the Pearlette seemed to be in pretty good shape when I received the camera, the bellows were clearly rotted. And by rotted, I don’t mean an occasional pinhole here and there, we’re talking entire corners that had become detached, allowing light to pour into the film compartment. It was clear that no amount of liquid electrical tape could be used to patch the bellows to make them light tight would work. If I wanted to shoot this camera, I would either need to replace them or figure out a way to shield the entire bellows.

I went with the latter method and using some left over card stock and a whole bunch of electrical tape, I completely covered the entire scissors mechanism and bellows, constructing a sort of “shield cone” around the camera. It prevented me from folding it shut, but at least I would be able to shoot a test roll through the camera without completely ruining my film,

My Results

With my crude attempt at covering the Pearlette’s heavily degraded bellow in place, I wanted to take the camera out and see how well it did. With any other format of film, whenever I am not certain about a camera’s performance, I usually default to a bulk black and white film that I have a bunch of as I don’t want to risk wasting color film which is increasingly difficult to find these days. For 127 cameras however, it’s the other way around as I have nearly 100 feet of bulk 46mm wide Fuji color Professional 160S color film which I can cut and tape to 127 backing paper. I went into my dark room (aka basement bathroom) and loaded up a roll of color 127 and took the Pearlette for a spin!

Usually when shooting a camera for the first time, I have some general idea of what to expect. Maybe it is because of a familiar form factor, camera model, or lens, but usually I know where my expectations should be as I pull freshly developed film from my Paterson tank.

Being the oldest Japanese camera I’ve ever shot, using a lens I know very little about, on expired 46mm film that I had to bulk load onto 127 backing paper, in a camera whose bellows was so full of holes, I needed to completely cover it using cardboard and electrical tape, I had absolutely no idea what I was about to see.

To my surprise, six out of eight images were good, VERY good! Of the two that didn’t turn out, one the shutter didn’t fire (or I double advanced the film), and the second was that I didn’t quite get the film correctly positioned on the backing paper and I shot half the image off the edge of the film.

But of the six that are in the gallery above, holy cow! For a lens which is basically two meniscus lenses glued together, the images show incredible sharpness and detail! Softness and a small amount of vignetting is visible, but not anywhere close to bad. I’ve seen 6×9 cameras with German triplets look softer near the edges than on the Pearlette. Everyone knows Konishiroku and later Konica made great Hexar and Hexanon lenses, but clearly their understanding of optics extends to their earlier two element lenses!

Interestingly, it would seem my observations are not unique as I’ve read on a number of other sources that the two element Meniscus Achromat lens developed by Rokuoh-sha was sharper when stopped down than the other available 3-element lenses, but suffered from extreme softness when used with a larger diaphragm. This explains why the Meniscus Achromat was never available at anything larger than US 8 (f/11).

A Digital Pearlette? Many people today adapt interchangeable lenses to digital cameras using a simple adapter, but what about cameras like the Pearlette in which the lens is non-removable. Sure, you could hack the camera apart, separating the lens and shutter from it, and devise some sort of clever way of attaching it to a digital camera, or you could do what one Japanese user did and adapt the entire camera to a digital camera. Using Google Translate, I was able to read his conversion of removing the rear door and 3D printing some sort of baffle that covers the film plane, and then by mounting a lens adapter for his Canon EOS D60, he was able to mount the entire camera to the Canon as if it were a lens. In a separate post, he shares some sample images shot with this setup using the same Meniscus Achromat doublet that my camera has, and the images are impressive.

Using the camera was hampered by my hack job of covering the bellows, but extrapolating what the camera might have been like in good condition, I quite enjoyed using it. I’ve shot a Kodak Vest Pocket a number of times, and I prefer the location and feel of the shutter release on the Pearlette more. When holding the camera in portrait orientation, I found that using my right thumb to press down on the shutter release was most comfortable, but in landscape orientation, it was in a perfect location for my right index finger. On a folding camera that uses 120 film, the lens and shutter are too far forward for your finger to reach across the length of the bellows, but the smaller dimensions of this 127 camera made it a perfect fit for my average size adult male hands.

Of the two viewfinders, I used the reflex one the most. Wearing prescription glasses, I cannot get my eye close enough to use the wire frame finder, so I didn’t bother. With the reflex finder, the biggest challenge is that if you hold it too close to your face, most of the image disappears, but at the distance it needs to be to see the full image, it’s too small to make out a lot of detail, so my priority was just making sure I was holding the camera level and getting what I intended to photograph at least somewhere in the frame. I figured that since I wasn’t attempting any tight compositions, I would be fine.

The only real con to the camera is in the fixed focus and limited exposure options the Pearlette offers. Even with faster Hexar and Zion lenses which were available on the more expensive Pearlettes, the focus is still fixed. Looking at the images I got with the Meniscus Achromat lens above though, I honestly don’t know how much better an upgraded model might be! Still, I can’t help but wonder what a Pearlette Model 2 with a German inspired shutter and focusing helix might have added to the camera.

The Pearlette proved to be a popular camera that helped launch the Japanese photo industry for good reason. This was an excellent first attempt that took the best of what the Americans and Germans were doing at the time, while simultaneously improving and simplifying the process at the same time. I have no doubt in my mind that Japanese photographers of the 1920s, 30s, and 40s were proud of their Pearlettes and cherished the images they got from them. Having now shot one myself, and being able to step into the shoes of the men and women who used them long ago, I am proud to include this camera in my collection, as I am sure you would too.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pearlette

http://www2f.biglobe.ne.jp/~ter-1212/sakura/pearlette.htm (in Japanese)

http://aya3photo.sakura.ne.jp/aya-2/pearlette_ca.html (in Japanese)

http://ranzosha.web.fc2.com/d008pearlette.html (in Japanese)

http://www5e.biglobe.ne.jp/~clenssic/camera-pearlette.html (in Japanese)

I’m in process of restoring a truly beautiful 1933 Pearlette, by replacing its tattered bellows with a set removed from a late-1930s model.

The 1933 has an Echo shutter in a decorated bezel, even fancier than your example. Its lens is an Optor 75/6.3 … one source states this lens is an Asahi product, which would put it at the same rarity level as the Asahi lens on the Press Van.

As good as your results were with the meniscus lens version, I hope the Asahi/Optor performs even better.