This is a Minolta X-700, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by Minolta of Japan between the years 1981 and 1999. It was the last advanced manual focus Minolta SLR before the auto focus area and had a large number of features including both Aperture Priority and Programmed Auto Exposure. It had an electronically controlled and step less shutter with TTL off the film metering via a Silicon Photo Diode meter. It featured motor drive couplings which when attached to the proper motor drive could fire it’s shutter up to 3.5 frames per second, and had one of the brightest viewfinders of any manual focus camera ever made. The camera was Minolta’s most successful model since the SRT-101 and remained in production for nearly 20 years.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50 mm f/1.4 Minolta Rokkor-X coated 7-elements in 5-groups

Lens Mount: Minolta SR Bayonet (supports MC and MD lenses for AE)

Focus: 1.75 feet / 0.5 meters to Infinity

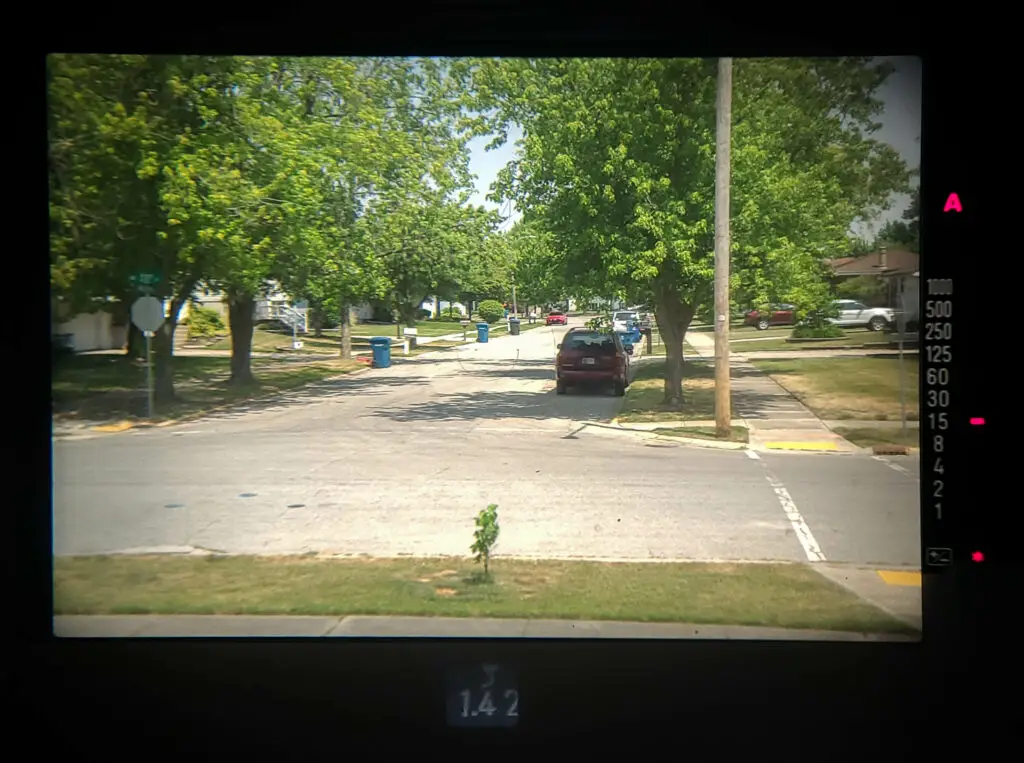

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with Full Information Finder, 95% Field of View, 0.9x Magnification

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds (Automatic): 4 – 1/1000 seconds, step less

Speeds (Manual): B, 1 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Silicone Photo Diode TTL off the Film Meter w/ Aperture Priority and Programmed AE

Battery: (2x) 1.5v SR44 / S76 Silver Oxide Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe X Flash Sync with PC Terminal for FP and M Sync, 1/60 X-Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer, DOF Preview, Auto Exposure Lock, Audible Warnings, Motor Drive Coupling

Weight: 802 grams, 494 grams (body only)

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/minolta_pdf/minolta_x-700.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Minolta X-700 was one of Minolta’s most successful and longest produced cameras the company made. It’s success was for good reason as it was an awesome camera with excellent ergonomics, a long list of advanced features, an excellent viewfinder, support for a wide range of accessories, and it used Minolta’s Rokkor lenses which were well regarded as some of the best available. If the camera sounds too good to be true, it does have a couple weaknesses, such as it’s cloth shutter with 1/60 X-sync, limited manual exposure metering, and an unfortunate reliability problem with capacitors that often fail on these models. If you don’t use flash, have no interest in manual exposure, and know how to fix your own cameras, the X-700 is tough to beat! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 11.0 | ||||||

History

Minolta’s SLR output from the 1960s and 70s can best be summarized as “the next best thing” in that the company was always looking for ways to push the standard of what everyone else was doing by incorporating features and designs into their products that was ahead of most of their competitors.

They did it in 1962 with the Minolta SR-7 having the first 35mm SLR with a built in coupled CdS exposure meter, they did it again in 1966 with the Minolta SRT-101 which not only was the first 35mm SLR with open aperture TTL metering, but was also the first camera ever to have matrix metering via it’s two CLC cells, and in 1971, Minolta released the X-1/XK/XM which was the first SLR with an electronically controlled shutter supporting aperture priority automatic exposure, and then in 1973.

In 1974, partnering with the Japanese shutter maker Copal and Ernst Leitz of Germany, Minolta released the XE/XE-1/XE-7 which was an all new advanced consumer 35mm SLR with an electronically controlled vertically traveling shutter, that although didn’t come with any new features, it had an unusually high number of improved features, combining quality, durability, and performance into a model that was lightweight and affordable. The XE was a premium camera that had more technology than the best system cameras of the day.

Minolta continued to push the limits of what could be done in a 35mm SLR with the XD/XD7/XD11 from 1977. Following up the successful XE, the XD had a more compact and lightweight body, improved the viewfinder with a brighter screen and a full information display, but most importantly, was the first 35mm SLR with both Aperture and Shutter Priority automatic exposure. If so much automation wasn’t your thing, the camera could also shoot in full manual with metering assist to make sure you got the exposure correct. In order to accomplish the feat of shutter priority AE, a revised Minolta bayonet lens mount was created. These new lenses were labeled “MD” lenses which allowed the body to control the aperture automatically. As with the XE, the XD was built in conjunction with Leitz and was the basis of the highly successful Leica R4, R5, R6, and R7 models.

Why All the Model Numbers? If you were curious why the same Minolta cameras had different model names depending on the region of which they were sold, this has to do with a common practice of “gray market dealers” who would import cameras from other markets, taking advantage of favorable exchange rates, lower taxes, and in some cases, less import tariffs. By importing cameras, rather than obtaining them through official channels from the distributor, retailers like Adorama and B&H could sell the cameras at a discount, undercutting other dealers. Strangely, the Minolta X-700 is one model that had the same name everywhere it was sold. This practice of having different names in different regions for the same cameras was not unique to Minolta, as Nikon, Olympus, and some other manufacturers did it too.

The period of time between the mid 1970s and early 1980s saw many advancements in automation technology used in cameras. In a short period of time, many camera makers employed electronically controlled shutters, smaller more compact bodies, more advanced types of auto exposure, and an increased use of technology. In addition, more and more advanced technology was tricking downward into more consumer friendly models. Entry and mid level cameras were no longer the primitive models they were only a few years before. Everyone wanted the latest and greatest, so the demand for an advanced mid level camera was stronger than ever.

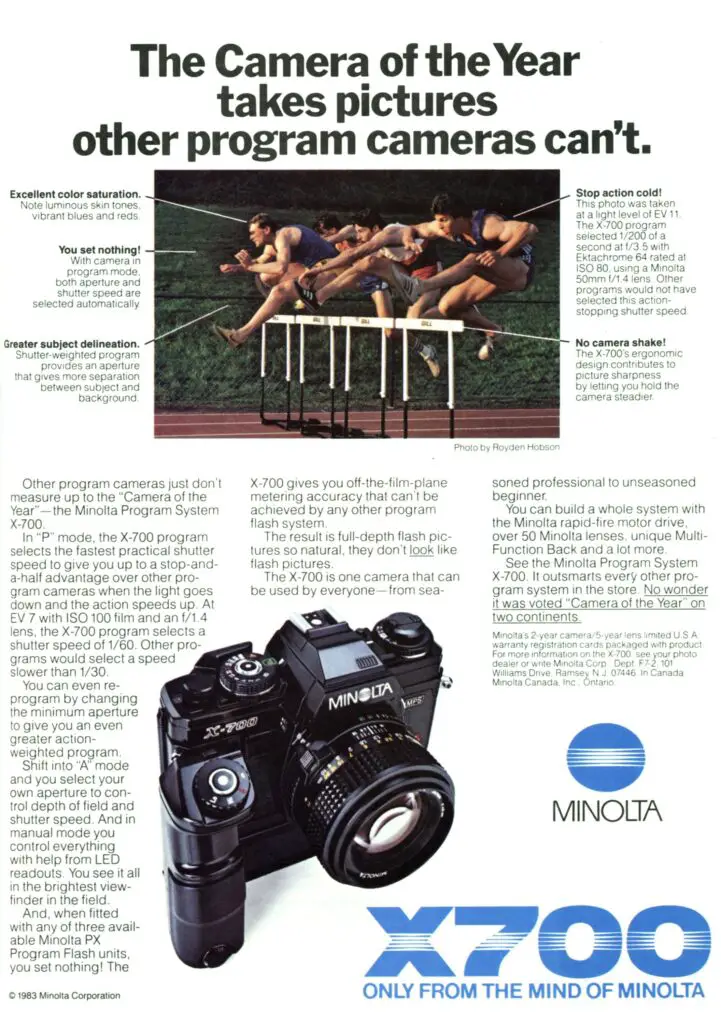

In early 1981, an all new model called the Minolta X-700 was announced that would attempt to fill the gap between the top of the line XD and the more consumer friendly XG series. In what would appeal to those wanting the simplest possible means of operation, the X-700 would be the company’s first camera with full programmed automatic exposure, allowing the camera to handle both shutter speed and aperture settings to obtain the best possible exposure in the most shooting situations. Like the previous model, lenses with the MD coupling were required to use the new Program mode, however earlier MC lenses could still be used in aperture priority automatic exposure. Unlike the XD, the X-700 did not support Shutter Priority AE mode by itself, but this was hardly an issue as anyone looking for a Program mode, likely wouldn’t need multiple other AE options.

In early 1981, an all new model called the Minolta X-700 was announced that would attempt to fill the gap between the top of the line XD and the more consumer friendly XG series. In what would appeal to those wanting the simplest possible means of operation, the X-700 would be the company’s first camera with full programmed automatic exposure, allowing the camera to handle both shutter speed and aperture settings to obtain the best possible exposure in the most shooting situations. Like the previous model, lenses with the MD coupling were required to use the new Program mode, however earlier MC lenses could still be used in aperture priority automatic exposure. Unlike the XD, the X-700 did not support Shutter Priority AE mode by itself, but this was hardly an issue as anyone looking for a Program mode, likely wouldn’t need multiple other AE options.

Fun Fact: The Minolta X-700 was the first camera released to feature Minolta’s new “Rising Sun” logo which the company would use until it’s merger with Konica in 2003. The new logo featured a solid circle in place of the letter “O” with horizontal lines to hint at a morning sunrise, a common symbol of Japan and it’s culture.

The following First Look for the Minolta X-700 comes from the January 1982 issue of Popular Photography.

Contrary to some information online, the X-700 was not intended to replace the XD, it was a clear attempt to pack as much technology into a camera as possible, while keeping the price in check so that it didn’t escalate out of reach for the intended demographic.

In order to keep costs reasonable, the X-700 omitted a few things that the XD had. The most notable omission was the loss of the vertically traveling metal shutter. The X-700’s horizontally traveling cloth shutter was seen as sort of a step back, as was it’s slower 1/60 flash sync compared to the XD which could reach 1/100. In addition, the X-700’s manual exposure mode did not allow you to match your selected exposure setting with one that the camera was recommending. In order to use the meter in manual mode, you’d need to look through the viewfinder at the recommendation, and then lower the camera from your eye to make the change. This likely was not an issue for less advanced photographers, but prevented the X-700 from taking the place as an advanced “prosumer” model like the XD.

Not all was bad though as the X-700 added a more advanced flash metering mode which supported four new electronic flashes, including the macro 80PX flash ring which allowed for accurate flash metering while shooting macrophotography. The camera had a new audible beep mode which would alert you to underexposure or slow shutter speeds, and could also beep in sync with the countdown for the self-timer.

New accessories such as the Multi-Function Back which supported a six digit date imprint feature and added new features to the camera such as an intervalometer for stop motion photography, and a clock. A new wireless controller allowed the photographer to control the shutter of the X-700 from up to 200 feet away, plus support for both the Minolta Motor Drive 1 with additional hand grip and auxiliary shutter release and the smaller and slightly slower Auto Winder G available for the XG and XD series.

All of this technology, plus the use of weight saving glass filled polycarbonate plastic and a simpler shutter, resulted in a camera with a retail price about $100 cheaper than the XD11. At it’s release, the X-700 carried a retail price of $399.50 body only, or $438.50 with a 35-105mm f/3.5-4.5 zoom lens. When adjusted for inflation, these prices compare to $1230 and $1350 today.

The following Lab Report goes into more detail about the X-700 than the First Look above, and comes from the November 1982 issue of Popular Photography.

Reactions to the Minolta X-700 were very positive and the camera sold well. For the beginning photographer who wanted an upgrade from more basic SLRs to a camera with features rivaling the most advanced models without paying a premium price, the X-700 was a good value, and for the professional photographer who wanted a backup camera for their more expensive system cameras, the X-700 was still a very capable model

Fun Fact: Minolta’s advertisements at the time proudly proclaimed the Minolta X-700 to be the European Camera of the Year, an award given out by the Expert Imaging and Sound Association (EISA) in various consumer electronics categories. The X-700 won the award in the very first year EISA awarded it to cameras. It’s most recent award went to the Nikon Z9 digital mirrorless camera in 2022.

In the Lab Report above, the review is largely positive, with minor criticisms of the Programmed AE mode favoring overexposure in tricky lighting situations, and that compared to other cameras with Program AE, the X-700 favored faster shutter speeds and wider apertures which was good for sports and fast motion. The use of lighter weight plastics was given good marks for durability and that Minolta still incorporated steel in places like the base plate and tripod socket where it needed it most, while not adding significantly to the camera’s weight. The assembly and finish of the camera was given a Good rating and that performance after stress testing matched pre-stress test numbers.

As was the case with the Minolta’s earlier XG and XD models, the electronic touch shutter release and arrangement of shutter speed control and fast action film advance lever were positively received. The acute-matte viewfinder screen was one of the brightest ever tested and compared favorably with the best SLRs of the era. And of course, no review of a Minolta SLR would be complete without mentioning the optical proficiency of Minolta Rokkor lenses. That the X-700 supported not only the new MD lenses, but all earlier Minolta SLR lenses dating back to the original SR-series was a huge plus to photographers looking to maintain backward compatibility.

A majority of Minolta X-700 cameras were sold with a black finish, but a small number were produced in Japan with a chrome finish. The chrome X-700s were identical with the exception that they lacked the exposure lock feature. These cameras are quite rare today.

In 1983, with the X-700 selling well and the company discontinuing it’s earlier XG series, two additional models in the series would be released. The X-500/X-570 was in some ways, both a step down and step up model, both subtracting and adding some features from the X-700. Like the earlier XD, with the X-500 returned a full information viewfinder which could show both selected shutter speeds and apertures in manual focus mode, allowing for accurate metering in every exposure mode, even manual.

In addition, the X-500 tweaked many of the X-700’s features allowing for the photographer to set a speed slower than 1/60 when using flash synchronization, metering while still using the depth of field button, support for a wider range of film speeds, and better support for Minolta PX flashes and non Flash-TTL flashguns.

At the same time, a third model, the X-300/X-370 was released as the entry level model, losing Programmed AE, Flash-TTL, the full information viewfinder, removable film backs, and DOF preview. It also had a cover over the shutter speed dial, only showing the selected speed, plus a few other very minor revisions.

Both the X-500 and X-300 sold with an approximate 20% discount from the models above it in the lineup making them much more appealing to those who wanted a high regarded camera like the X-700 but without some of it’s more ambitious features.

The Minolta X-700 was a very good, but not perfect camera. That didn’t seem to matter as not only did it sell well, but it would end up being one of the longest produced cameras ever made by the company. The X-700 was in production for 18 years, from 1981 until 1999 a feat partially helped by the fact that in 1985, Minolta would enter the world of auto focus SLRs with the Maxxum 7000 and an all new, and incompatible lens mount. For photographers who didn’t trust, or had no use for auto focus, the X-700 remained a popular manual focus option for the same reasons the Nikon F3 and Pentax LX manual focus SLRs were produced for an unusually long time.

A couple of minor changes happened to the Minolta X-700 throughout it’s 18 year production. The most notable is a change to the type of two capacitors used, one under the top plate and another under the bottom plate, for the metering system. The original design of the X-700 called for tantalum capacitors which were very expensive but very durable. At some point in the mid 1980s, the original tantalum capacitors were replaced with much less expensive electrolytic capacitors which are more likely to fail over time. There is no way to externally tell the difference between a Minolta X-700 with the tantalum or electrolytic capacitor, but if you have an electrolytic one, there is a very good chance the electronics are dead on it today.

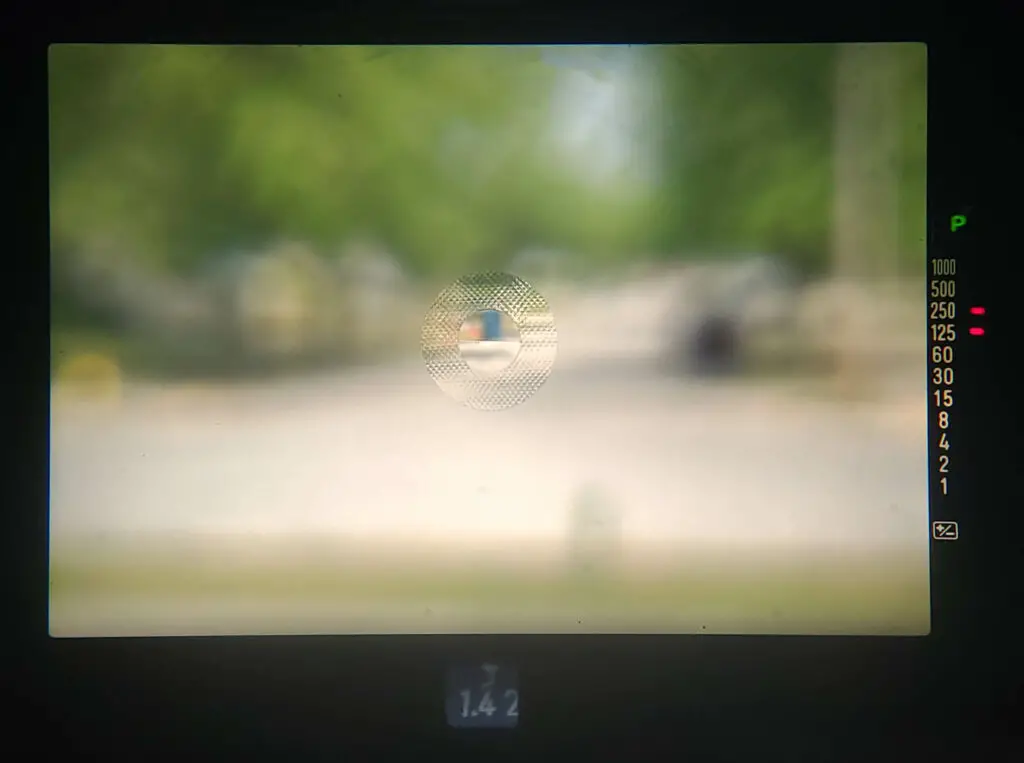

Replacing failed electrolytic capacitors is possible by trained technicians, but not something that should be attempted by a novice. If you would like to check your camera to see which one you have, remove the bottom plate and look for a blue electrical component near the brass electric connections for the motor drive. If you have a blue capacitor like in the image to the right, you have the earlier tantalum ones.

Today, most Minolta SLRs are well regarded. Models from the original SR-series to the long lived SRT, professional X1, the tough but advanced XE and the electronically advanced XD series are frequent favorites of collectors and shooters alike.

Even though it wasn’t the company’s most advanced model, the Minolta X-700 seems to be especially regarded, possibly due to how long it was in production, more people remember it. It’s nice mix of modern features and compact design, along with manual advance and capability for manual exposure make it appealing to a large number of collectors and film shooters alike.

My Thoughts

The most commonly asked questions in camera collectors groups usually start with “What is the best SLR camera that…”, and answers to those questions are almost all over the place with a huge number of recommendations. The best answer however, is usually along the lines of “there is no best”. This is true whether you are talking about cameras, computers, televisions, or pretty much anything as everyone has their own priorities, and one person’s “best” camera might check off all the right boxes for them, but not someone else.

So, if there is no best, perhaps we might still get something closely resembling an answer by expanding our question to “What is a really good SLR camera that checks off the most number of boxes for most collectors?” Cameras mentioned in response to that question likely will include well equipped pro and semi-pro models like the Nikon F3 or FM3, Canon F-1 or A1, Olympus OM-4, or the Pentax LX.

While each of those models are certainly worthwhile cameras that should appease anyone wanting the best of the late modern manual focus era, there’s one model that I think it deserving to be mentioned in that group too, the Minolta X-700.

The X-700 was the last semi-professional manual focus SLR Minolta would release before the auto-focus era. When it was released in 1981, it was marketed as a state of the art camera with a long list of advanced features. Although it didn’t go head to head with professional cameras like the Nikon F3 or Canon New F-1, it came very close, with the most obvious feature omission being the lack of interchangeable viewfinders.

The Minolta X-700 fits a tremendous amount of technology in a light weight and compact body. The camera was quite a bit smaller than the F3, and about the same size as an Olympus OM-4. The camera benefitted from composite materials, weighing less than 500 grams without a lens, yet still having a sturdy build quality that instilled confidence in it’s toughness.

When I first picked up the X-700, I marveled at how well it felt in my hands. Neither too big, nor too small, with a finger grip similar to the Nikon F3 that allows for sure handling without worry of the camera slipping from your hands. For anyone who had held one of Minolta’s earlier X-series cameras like the XD-11 or XG-7 which came before it, the camera shares a similar design ethos, plus the electronic touch shutter release, and extremely bright and useful viewfinder.

Up top, the X-700 packs quite a number of controls into a tight space, yet somehow manages not to feel cluttered. On the left is the rewind knob with fold out handle and combined film speed and exposure value adjustment controls. Both the film speed and EV controls are normally locked in position and cannot be changed until releasing the lock. To the right of the control is a release button which you press and hold while turning the EV dial up to 2 stops over and under. To change the film speed, lift up on the perimeter of the ring while rotating it to select ASA film speeds from 25 to 1600.

Above the pentaprism is a hot shoe supporting TTL and non-TTL flash metering. Minolta produced four electronic flashes which supported the X-700’s TTL flash metering. The four models were the 280PX, 132PX, 360PX, and the macro 80PX flash ring. For studio work, the X-700 also supports a PC sync port on the side of the mirror box.

On the right is the combined shutter release, shutter speed, and exposure control dial. The shutter release is similar to other X-series Minoltas that use an electronic capacitance touch feature which detects the presence of your finger, without having to apply any pressure to ready the meter and get it ready for shooting. With the camera powered on, gently resting your finger on the shutter release will awaken the meter and keep it responding for about 15 seconds, before going back into a power save mode. This ensures that the camera is always ready to make an exposure without any delay, and while also saving on battery power. To totally power off the camera, a slider around the perimeter of the shutter speed dial turns the camera on and off. There are two settings for one, one which also includes an audible beep which warns you of over and under exposure.

The shutter speed wheel has manual settings from 1 to 1/1000, plus Bulb. Two additional settings, an orange A and green P select aperture priority and programmed AE modes. In order to use the Programmed AE exposure mode, you must use Minolta MD lenses which have additional contacts which are required to control the diaphragm. With Minolta MC lenses, only the shutter priority AE mode can be used. The shutter speed dial becomes locked in either the A or P modes, preventing accidental changes when in storage. To unlock the dial from either mode, a small button above and to the right of the dial must be pressed while rotating the dial.

The film advance lever has an ergonomic plastic tip for comfort and has an approximate 30 degree stand off which readies it for the next exposure. Unlike Nikon SLRs of the same era who use this stand off position as a power switch, on the X-700, the meter can be readied and the shutter fired with or without the lever in the ready position. Advancing the lever is smooth and quick with an approximate 130 degree motion. A full advance must be done in a single motion as smaller intermittent movements are not allowed, not that you’d need them anyway. Above and to the right of the film advance lever is a small window which is used to see that film is properly advancing through the camera. Under normal operation, a white bar should jiggle as you wind the camera. Finally, to the right of the lever is the automatic resetting exposure counter. The exposure counter is additive, showing how many exposures have been made since the film door was last opened.

The bottom of the camera has a centrally located metal 1/4″ tripod socket, the round opening for the battery compartment, rewind release button and both mechanical and electrical connections for an optional motor drive. The X-700 supported both the faster Minolta Motor Drive 1 with additional hand grip and auxiliary shutter release and the smaller and slightly slower Auto Winder G both of which worked on the X-370 and X-570 cameras.

The sides of the camera each have forward facing metal strap lugs whose orientation allows for better balance, preventing the camera from tilting forward while hanging from your neck with a heavy lens mounted. On the left side of the mirror box is a chrome button for releasing the lens, a threaded cable release socket, and a black plastic depth of field preview button.

Around back there is the rectangular eyepiece for the viewfinder which has grooves on the side supporting a variety of viewfinder accessories. In the center of the door is a film box reminder frame with a DIN to ASA conversion chart for shooters of European film. To the right of the frame is a thumb hump, which like the finger hump on the front of the camera, enhance the ergonomics of your right hand, allowing for a more secure handling of the camera.

The film back opens with a firm upward tug of the rewind knob. The right hinged door reveals a typical early 1980s SLR film compartment. The door is removable via a sliding lever on the hinge for installing one of two optional data backs available for the X-700. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed and multi-slotted plastic take up spool. Loading in a new roll of of film is quick and easy as you only need to attach the leader to one of the four slots gripping a sprocket on a tooth next to each slot and then giving the camera couple advances to wrap the leader around the spool. The film gate is of normal design with unpainted metal rails above and below the gate.

Inside of the door is an extra large black painted film pressure plate covered in divots which help reduce friction as film passes over it. To either side of the pressure plate are metal brackets which help maintain pressure on the film and cassette as they are loaded in the camera. The X-700 uses foam light seals on both the door hinge and inside both channels above and below the film compartment. Although the ones on this example were still in good physical condition and likely were still doing their jobs, as is the case with all foam light seals, they will eventually crumble away and allow light to leak into the film compartment, so replacing them is essential for prolonged operation.

The Minolta X-700 uses Minolta SR/MC/MD bayonet mount lenses, so the exact look of each lens will vary, but in the case of the Rokkor-X PG 50mm f/1.4 lens mounted, this is an MC lens, which means it does not support the X-700’s full Programmed AE mode. If using a Minolta Rokkor lens, the easiest way to tell the difference between an MC and MD lenses is to simply look at the vanity ring on the front of the lens. All first party Minolta lenses will have the letters “MC” or “MD” on the ring, but in addition another way to tell is by looking at the aperture ring. All MD lenses will have the smallest aperture number in green, whereas MC lenses it will be white. In order to use the camera in P mode, you must set the aperture ring to this green setting.

For this lens, positive click stops between f/1.4 and f/16 are closest to the body with a fixed depth of field scale, and then a focus distance scale with marks in both feet (in green) and meters (in white). The focus ring is covered in grippy rubber, and on this example was not peeling, cracked, or turning white like some do. A red letter “R” is on the depth of field scale between the white triangle and white number 8 to indicate the focus mark when using infrared film.

Changing lenses on the X-700 is as easy as all Minolta SLRs, with the lens release button near the 2 o’clock position around the lens mount, on the side of the mirror box. Press and hold the release button while giving the lens a slight counterclockwise twist and it will come off. Putting the lens back in is the opposite of removing it. Line up a red dot on the lens with a red dot on the metal lens mount and twist the lens clockwise until it locks into position.

Above and to the left of the lens mount is a plastic switch which controls both the AE lock and electronic self-timer. With the camera to your eye in either A or P mode, press and hold this button to lock in a meter reading. This is useful if you need to compose your image in strong back or foreground light and then recompose your image to get correct exposure.

To use the self timer, lift up on this button until it clicks into an upper position with a red mark visible. With the self-timer engaged, the next time you press the shutter release, a red LED below the button will begin to blink slowly at first, and then rapidly before firing the shutter after an approximate 10 second delay. If the camera’s power switch is in the On position with the audible beep, the camera will also beep in synchronization with the blinking red LED as the self-timer is counting down. Cancelling the self-timer is done by pressing the raised button back into it’s original position. After using the self-timer, it remains enabled, so you must remember to disable it after each time you use it.

The viewfinder on the Minolta X-700 is a mix of good, and depending on your expectations, slightly disappointing. For the good, it is large and very bright.

The focus screen is one of the brightest I’ve used and is very easy to get accurate focus, even in dim light. Although the entire viewfinder is not interchangeable, the focus screens are. When the camera was released, a total of nine focus screens were available for a variety of uses. The standard screen that most X-700s will have is the type PM screen which has a split image rangefinder surrounded by a microprism collar. Changing the screens is done through the inside of the lens mount using a special tool which Minolta includes with the purchase of additional screens.

Below the screen in the center of the viewfinder is a Judas window which allows you to see the chosen aperture number on the lens mounted to the camera. On the left is a shutter speed scale illuminated by light entering through the viewfinder. Shutter speeds from 1 to 1000 are shown vertically, with a setting at the bottom indicating that an EV plus or minus adjustment has been made. To the right of each speed is a red LED which indicates that speed has been chosen by the meter. If two LEDs are lit, it means a speed in between the two has been chosen. Red triangles above and below the scale will illuminate if a speed faster than 1000 or below 1 has been detected. Depending on the exposure mode chosen, one of three letters, red letters M or A, or a green P will display above the scale to let you know the camera is in manual exposure, shutter priority AE, or programmed AE modes. If the P is blinking, it means that either you have not mounted a Minolta MD lens or that one is mounted but the aperture ring is not set at it’s minimum aperture. The camera will still attempt to choose an appropriate exposure combination, but it will likely be incorrect.

Although there is a lot to like about the X-700’s viewfinder, two shortcomings which disappointed some people upon it’s release are that unlike the Minolta XD-11 which came before it, there is no way to see the chosen shutter speed in manual exposure mode with the camera to your eye. The X-700’s meter will still make recommendations for the given composition, but the scale does not show you what you have. This is a feature that not only the XD-11 had, but cameras like the Nikon FE, Canon A-1, and several others which came before it could do. Another shortcoming is that since the scale shows the slowest speed of 1 second, yet the metering system is capable of speeds as long as 4 seconds, there is no way to know the difference between a 1 second and 4 second exposure. Certainly, neither of these omissions were deal breakers for an otherwise great camera, but at least suggested Minolta’s priorities were beginning to shift away from people wanting full manual control of their exposure.

The Minolta X-700 is a heck of a camera with a great deal of technology and innovation beyond what I’ve typed here. It was a true “prosumer” camera much like mid to upper end digital mirrorless and DSLRs are today. It packed in a tremendous amount of technology into an easy to use, lightweight, and compact body. It supported all of the company’s excellent Minolta lenses, and had a feature set that likely appealed to 99% of photographers out there.

But wait a minute, I’m getting ahead of myself here. What is it like to shoot? Are the feature it does have good enough for the 99%? Keep reading…

My Results

I actually shot the Minolta X-700 twice during my test for this review, but the first images were on a heavily expired roll of Kodak BW400CN that turned out so grainy and dark the images were not usable. I ended up discarding those scans and instead shot a quick roll of Fuji 200 in late fall at the Lake County Indiana fairgrounds. As I had shot well over a dozen Minolta SLRs with excellent Rokkor lenses, I knew the images would look good, and I figured I should pay more attention to the user experience of the Minolta X-700 than the images it would make.

Shooting the Minolta X-700 is less about the results you get and the experience and capabilities of the body. Minolta’s Rokkor lenses are great. Everyone knows this. I’ve repeatedly gotten excellent results with other Minolta cameras using these lenses, over, and over, and over again.

Images are sharp corner to corner and show excellent contrast, accurate colors, and do not exhibit any of the optical anomalies often associated with lesser lenses. For as much respect as I have with A-list camera and lens makers from Japan, Germany, and other countries, I have an unpopular opinion that you really can’t see the difference between 50mm lenses. Even with other focal lengths, you have to get into some pretty specific “pixel peeping” with high resolution digital sensors before you’ll ever see any noticeable differences between a Rokkor, Nikkor, Hexanon, Canon or Takumar lens.

Since we know the images are wonderful, using the X-700 that made them, I have a couple of observations. For starters, the camera has excellent balance and almost perfect ergonomics. While you’ll never hear me complain about larger “full bodied” SLRs from the 50s, 60s, and early 70s like the Minolta SR-7, Nikon F2, or Konica FS, as they fit my hands fine, but the slightly more compact size of later SLRs like the Olympus OM-2, Nikon FM, and Minolta X-700 are just a little “more” fine! The small finger grips on the camera’s right side and the thumb hump on the back are perfectly located to allow for comfortable handling in a variety of situations. While I would still recommend using a strap, gripping the camera is secure enough to allow for short ventures without a strap.

The viewfinder, specifically the viewing screen is excellent. Large and bright, I can easily see focus even in poor lighting. Pointing the camera at my computer monitor and looking through the viewfinder, the image is only barely less bright than looking at the screen without the camera. In real world shooting outdoors, the image doesn’t look any darker.

The fast action of the film advance lever, the easy turns of the large shutter speed dial, and the very short movement of the electronic capacitance shutter release button all work remarkably well. When I first started this site, one of my earliest reviews was for the Minolta XG-7 which has a similar shutter release and I was immediately drawn to it’s feel and use. Despite that camera being as old as I am, it felt “high tech” and modern.

The Minolta X-700 has a long list of features and support for accessories which likely made it appealing to a great number of professional and semi-professional photographers, but isn’t something I had any use for. Still, to support multiple motor drives, multifunction data backs, wireless triggers, and interchangeable focusing screens is very cool.

Without a doubt, the biggest disappointment of the camera is it’s return to a cloth focal plane shutter and top 1/1000 shutter speed. While the earlier Minolta XD11 also had a 1/1000 shutter speed, in an era when manufacturers were going with vertically traveling shutters with speeds of 1/2000 and up, the X-700 almost feels like a step back. The lack of being able to see your selected shutter speed in the viewfinder to match what the meter was reading isn’t as big of a loss as I thought it would be, as I didn’t shoot the camera in manual exposure mode. Since the camera was capable of both aperture priority auto exposure (the best kind) and programmed AE, I did my test in those modes. While I am certain some people would shoot the X-700 in manual exposure mode, with a literal wall full of manual exposure SLRs I could choose from, I wanted to experience the X-700 in the way I believe a majority of it’s original owners used it.

Whatever few omissions Minolta might have made with the X-700 to keep costs from spiraling out of control, it clearly worked, as the camera was very popular and was in production for 18 years. Bloggers like me can lament all we want about features we wish a certain camera had, but the reality is, Minolta made the right decision by omitting them. Clearly, an advanced consumer SLR with a cloth focal plane shutter, top 1/1000 shutter speed, and limited manual exposure modes wasn’t a problem for most people. If you absolutely want a Minolta SLR with a vertically traveling metal blade shutter and faster X-sync speed, get the Minolta XD11. If you want nearly everything the X-700 does, but with a full information viewfinder that allows you to match your exposure in manual exposure mode, get the Minolta X-570, you won’t miss anything the X-700 has that those don’t.

The Minolta X-700 is a terrific camera with almost everything anyone could ever want in an easy and comfortable to use 35mm SLR. It supports some of the best lenses ever made, has a great viewfinder, and a metering system that’s going to get the job done every time. There are many good reasons to buy one, but one that makes me hesitate to fully recommend it, is it’s poor reputation for reliability. The capacitor issue is real. Many owners of these cameras have experienced the problem, which require the capacitors on all but the earliest models to be replaced. It’s certainly doable, and you might even be able to do it yourself, so if you can get them replaced, then great, but for everyone else, the market for modern 35mm SLRs with good viewfinders, auto exposure, and support for excellent lenses is quite large. There are many similar cameras (even some by Minolta themselves) which likely have a better chance at working properly. Buyer beware.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Minolta_X-700

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minolta_X-700

http://www.mir.com.my/rb/photography/hardwares/classics/minoltax700/index.htm

https://high5cameras.com/all-articles/camera-reviews/minolta-x-series-x-700-x-500-x-300-review/

http://rokkorfiles.com/X-700.html

https://casualphotophile.com/2015/08/08/minolta-x-700-camera-review/

https://michael.werneburg.ca/review:-Minolta-X-700-camera

http://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/page_standard.php?id_appareil=11522

Nice article! While I don’t have the X700, I love my X570 and my XD7. I have also the odd, Japan-only X600, which is somewhat an X300/370, but instead of a split screen it uses focus confirmation with LEDs (like later AF cameras), and uses AAA batteries instead of button cells. And I have as well a SRT102 and an XE, but the XD7 and the X570 gets the most use…

Great post, Mike. Minolta made some great cameras. I’d also recommend the XD5 if you wanted the vertically traveling shutter and shutter-priority. It’s definitely missing a few things that the XD/11 has, but nothing that really counts. It’s possibly my favorite SLR.

One correction, though. In the “My Thoughts” section, you say: “In order to use the Programmed AE exposure mode, you must use Minolta MD lenses which have additional contacts which are required to control the diaphragm. With Minolta MC lenses, only the shutter priority AE mode can be used.” Shouldn’t it be, only the aperture priority AE mode can be used?

Thank you for the detailed info on capacitors, Mike. I side with many street and backwoods shooters in preferring the X570 over the X700, because of the viewfinder info readouts on the former.