This is a Zenit 16, a 35mm SLR made by Krasnogorski Mekhanicheskii Zavod (KMZ) in the former Soviet Union between the years of 1973 to 1977. It uses the M42 screw mount and has a CdS exposure meter with over and under indicators visible in the viewfinder. The Zenit 16 is unlike most other cameras in the Zenit family of SLRs in that it has a mostly plastic body with styling originally found in the Zenit-15 prototype. It was a simple camera with a short list of features, but offered a mechanically timed vertically traveling cloth focal plane shutter. The Zenit 16 was a short lived camera and did not sell very well, making them hard to find today, especially in working condition, but their distinct and interesting style makes them highly sought out by collectors.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 58mm f/2 Helios-44M coated 6-elements in 4-groups

Lens Mount: M42 Screw Mount

Focus: 0.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Pentaprism with microprism circle focus aide

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/15 – 1/1000 seconds

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Cell w/ viewfinder over/under lamps

Battery: (3x) 1.35v PX625 (Soviet РЦ-53) Mercury Battery

Flash Mount: Hot shoe and M and X Flash Sync, 1/125 X-sync

Other Features: DOF Preview

Weight: 927 grams (w/ lens), 635 grams (body only)

Manual (in Russian): http://www.zenitcamera.com/mans/zenit-16/zenit-16.html

Repair Manual (in Russian): https://mikeeckman.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Zenit16RepairManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Zenit 16 is an unusually attractive member of the Zenit SLR family, and was built with many innovative features in it’s shutter, instant return mirror, and exposure counter, but despite these features, the Zenit 16 works much like any other mechanical SLR. It supports semi automatic M42 lenses and when working, is just as capable as most other SLRs of it’s day. Despite it’s good looks and interesting technology, the camera is hampered by a dark viewfinder and strange location for the shutter release which may be of concern to some shooters. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for one of a kind design and features that went against the grain of what everyone else was doing. | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

Many eons ago, before there age of man existed large beasts that ruled the world. These giants roamed the land, the sea, and the air, and when they wanted to take a photo of something, they used a Zenit camera…

…okay, I’m obviously kidding, Zenit cameras haven’t been around THAT long, but they have been around a long time.

To tell the whole story of the Zenit, you need to start with the Zorki rangefinder, but in order to tell that story, you need to go back to the FED rangefinder produced at the Felix E. Dzerzhinsky Labour Commune, but if you’re going to go back that far, you might as well go back to the original Leica.

But this isn’t a review about the Leica, so to speed things up, we’ll just say the FED rangefinder was first produced around 1934 as a Soviet alternative to the German Leica. FED rangefinders were produced up until about 1941, but the factory’s location in Kharkov, Ukraine was within reach of the advancing German army, so the entire factory was disassembled and shipped elsewhere to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

After the war, with the original FED factory in ruins, the Soviet Union picked the KMZ factory near Moscow, Russia to resume production of the FED rangefinder. Cameras produced by KMZ were given the name Zorki, and at first, Zorki cameras were produced to the same specifications as the original FED cameras and looked nearly identical other than the name. In 1949, the FED factory in Ukraine was restored and new models began rolling out simultaneously with the KMZ Zorki.

Unlike the FED factory however, which was a labor commune operated by large amounts of orphaned children, the KMZ factory was more modern and capable of producing more advanced and higher quality products. In 1950, Single Lens Reflex models were starting to gain popularity in Germany, and not wanting to be left behind, the engineers at KMZ started work on a new Soviet SLR.

Rather than start over with a completely different design, the engineers took a Zorki body, removed the rangefinder and added a reflex mirror box with a pentaprism viewfinder. The camera shared the same bottom loading film design and rounded edges of the Zorki, and by proxy, the original Leica. It even retained the same M39 lens mount, but since the mirror box pushed the flange distance farther away from the film plane, new Zenit SLR M39 lenses needed to be created as M39 lenses would not be able to focus correctly.

Since a large amount of the camera already existed, early prototypes were shown as early as 1950 with a few more released in 1951. The new camera was called the Zenit, which translates in English to Zenith, or peak. Despite the relative simplicity of taking a Zorki and adding a reflex housing, the idea of turning a rangefinder into an SLR was something other manufacturers did too. In fact, the very popular and successful Nikon F SLR is built on the body of a Nikon SP, sharing many of it’s parts.

In addition, the inclusion of a pentaprism viewfinder was very forward thinking for 1950s, especially considering most SLRs of the era still relied in simpler waist level finders. Prior to the Zorki, the only commercially available 35mm SLRs with a pentaprism would have been the Italian Rectaflex or the Zeiss-Ikon Contax SLRs.

The first Zenit SLRs wouldn’t become available until 1952 but even then, they were produced in small numbers. Throughout the 1950s, the Zenit continued to advance, first adding flash synchronization, hinged rear back, and a self timer.

The Zenit 3M would be the last iteration of the Zorki based Zenit and would remain in production until 1970. In 1964, three new Zenit models, called the Zenit 4, 5, and 6 would all be released with an entirely new body, leaf shutter, DKL lens mount, and features like motor drive on the Zenit 5 and with the Zenit 6, the Soviet Union’s first 35mm zoom lens, the Rubin-1. Each of these three Zenit models were not very successful, with less than 40,000 made between the three models combined, and turned out to be a dead end in the Zenit line up.

But in 1965, another new Zenit called the Zenit E was released. Unlike the ambitious Zenits 4, 5, and 6, the Zenit E was a more traditional camera, offering a cloth focal plane shutter, retaining the M39 mount (later the M42) from the original Zenit, but adding an exposure meter and instant return meter. The Zenit E would go on to become one of the longest lived and best selling cameras ever made by any company in the world, staying in production (including variants) until 1991.

One of the reasons for the Zenit E’s success was it’s rugged and simple build quality that made it extremely reliable and cost effective to build. Many cameras were exported outside of the Soviet Union and sold under a variety of names as discount or beginners cameras, and with support for nearly every M42 lens ever made by any company, the possibilities were limitless.

But while the Zenit E dominated the sales charts, KMZ continued to look for new ways to improve upon the Zenit brand, releasing a large number of models, some like the Zenit 11 which changed very little to the ultra-rare Zenit 7 with it’s unique styling and new bayonet lens mount, and the Zenit 18 which was the first Soviet SLR with auto exposure.

In 1971, a new camera called the Zenit 15 was being developed by KMZ designer Anatoly Yakovlevich Padalko using a new body and shutter inspired by the earlier Zenit 7. Unlike the Zenit 7 however, the Zenit 15 would use the simpler M42 screw mount, and would lack any sort of exposure meter.

Note: KMZ actually made two different cameras called the Zenit 15. The one mentioned in this article was the original, but a second Zenit 15 model was released by BeLomo between 1984 and 1985 and was just a name variant of the Zenit TTL with slightly different cosmetics.

Although the Zenit 15 was never put into production, a variant of it called either the Zenit VS Semiautomatic or the Zenit 15 Semiautomatic used the same body as the Zenit 15, but added a coupled TTL exposure meter. Although this camera was also never put into production, it evolved into yet another model called the Zenit 16.

The Zenit 16 would begin production in 1973 and would be the first of a new generation of Zenit SLRs to hit the market. The camera retained the distinct looks of the original Zenit 15 model, but came with a large number of innovations many of which are not obvious from the outside.

The one that is however, is a new vertically traveling cloth focal plane shutter. While vertically traveling shutters were certainly not new, Zeiss Ikon had created a “garage door” style vertical shutter in the original Contax rangefinder from 1932, most vertical travelling focal plane shutters were made of metal. The one in the Zenit 16 is made of cloth, which is very unusual.

Below is a slow motion video I made of the shutter on this Zenit 16 firing at 1/30 of a second.

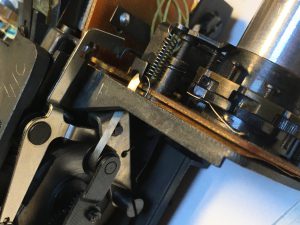

In an article from March 2020 posted on kosmofoto, renowned camera technician Oleg Khalyavin dissects a Zenit 16 and uncovers many of it’s secrets, explaining how the camera works.

This article goes into depth about how different the camera is from other mechanical SLRs and is worth a read. I don’t want to repeat too much of what Oleg covered in that article, so I’m paraphrasing the parts of Oleg’s article that I think are the most fascinating. All images below are the full resolution images given to me by Oleg directly.

- The reflex mirror is of an instant return type, but unlike most SLRs with this feature where the mirror returns to the down position with it’s own spring, on the Zenit 16, the mirror is directly connected to the second shutter curtain. When the shutter fires, the mirror springs up, the first curtain moves, and as the second curtain closes, it brings with it the mirror. The energy from the second curtain is what lowers the mirror again for the next shot.An additional benefit from this is the motion of the mirror acts as a dampener for the second shutter curtain, causing it’s motion to be more stable, and reduce strain on the cloth ribbons that pull on the curtains, potentially prolonging their life.

-

The large metal disc rotates each time the shutter is fired. A complete revolution takes 1/15 seconds. The timing of the shutter speeds is controlled by a large metal flywheel which is connected to both curtains using metal straps. When cocking the shutter, this wheel is rotated and the first curtain is raised. Unlike most focal plane shutters in which pressing the shutter release immediately starts the motion of the first curtain, then after a short delay the second curtain closes, on the Zenit 16, the delay occurs before the first curtain opens. The timing of the first curtain is variable depending on which shutter speed is selected, but the second curtain always closes at the end of the motion of the metal flywheel. When the slowest speed of 1/15 is selected, the curtain begins opening immediately after pressing the shutter release, the flywheel spins, and when it reaches the end, the second curtain closes. This motion takes exactly 1/15 of a second. For the faster speeds, the opening of the first curtain is delayed, causing the time between the first and second curtains to be shortened. At the fastest speed of 1/1000, almost the entire 1/15 second motion of the flywheel passes before the first curtain opens and the second curtain closes. You can notice this almost 1/15 second delay when firing the Zenit 16 at 1/1000, but it’s very minor.

This image shows the metal ribbon used to control shutter speeds, along with the adjustment screws in the upper right corner. Perhaps the coolest thing about this design is that the delay for each of the shutter speeds 1/30 through 1/1000 can be independently adjusted, allowing a technician to calibrate each speed without affecting the other speeds.

- The method for how the Zenit 16 both counts and evenly spaces exposures is unique in that it does not have a separate feeler shaft to count perforations like on most 35mm cameras. Instead, the take up spool has a single roll of sprockets that when advancing the film through the camera, measures the degree of rotation of the spool to know when to stop. Oleg isn’t entirely clear how this works, but it effectively combines the feeler shaft and take up spool into a single unit. He goes on to suggest that a June 1975 newspaper article explains that work was being done to develop a new type of 35mm camera that uses a similar exposure counting system, except with non perforated film, allowing them to increase the size of the exposure. Instead of a normal 24mm x 36mm exposure on most 35mm cameras, this system would have allowed for larger 32mm x 48mm exposures without having to redesign the camera for larger film!

-

An image of the Zenit 16 split apart showing the entire shutter assembly and film compartment. Finally, the last feature I found interesting might not seem that exciting, but is the simple construction of the camera’s outer shell. The entire body of the Zenit 16 is two large pieces of plastic that are separated by a seam running through the middle of the body. To open the camera, simply remove the rewind and advance levers, and four screws, and the entire camera comes apart. This allows for easy adjustment or repairs to the shutter or viewfinder by essentially pulling the entire camera out of it’s shell for service.

The Zenit 16 was clearly a camera that showed an ambitious direction for the Zenit family. Whether or not the Zenit 16 was intended to be a best selling model, or if it’s various advancements were proof of concepts to be used in other cameras is unclear, but with the benefit of hindsight, we now know that the Zenit 16 didn’t have a long life. According to sovietcams.com, a grand total of 11,114 examples were ever made.

In his article on kosmofoto.com, Oleg suggests that the priorities in the Soviet Union at this time were quantity over profit, and a more difficult and more expensive camera to build simply was not going to work. Even for those which were made, owners of existing Zenit SLRs wouldn’t have seen much of a reason to upgrade as despite being less advanced, the Zenit E was already good enough, and much cheaper.

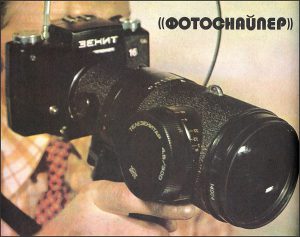

Had the Zenit 16 been more successful, there were plans from the very beginning to advance the line. A special use version called the Zenit 16M was made for use with the FS-4 Photo Sniper. The camera was very similar to the regular Zenit 16, with the biggest changing being the back plate shutter release was relocated to a more traditional location on the top plate.

In addition to the Zenit 16M, three more cameras were planned but never released, the Zenit 17, 18, and 19 with the following features.

- Zenit 17 – Similar to the Zenit 16 but with electrical feedback between the lens and body to transmit position of the chosen aperture. Possibly similar to the Pentacon Praktica VLC series (this is my guess, I am not sure of this though).

-

This drawing of the Zenit 18 prototype shows the Yantar zoom lens it might have come with. Zenit 18 – Same electrical feedback as Zenit 17, but with shutter priority auto exposure. This camera may or may not have come standard with a Yantar-5M-2 zoom lens.

- Zenit 19 – Same electrical feedback and shutter priority auto exposure as Zenit 18, but with a new standard Zenitar M2 50mm f/1.7 lens, titanium metal curtains, and expanded slow speeds down to 1 second.

It would seem that shortly after the release of the Zenit 16, plans for more advanced versions were scrapped and work for what would have become the Zenit 18 and 19 was shifted to a less complicated and more traditionally designed body.

Models with the names Zenit 18 and 19 would eventually be released in 1980 and 1979 respectively, with the Zenit 18 becoming the first M42 mount Zenit with automatic exposure, but neither shared the body and other features of the Zenit 16.

As was the case with many Soviet cameras of it’s day, finding the retail value of the Zenit 16 is very difficult. Most Soviet cameras were not advertised in magazines or catalogs like they were in the west, so even when you do find a price of them, calculating a conversion ratio for they cost with today’s inflation adjusted dollars is impossible.

The article for the Zenit 16 on zenitcamera.com says that the camera had patents in six different countries, but doesn’t say which ones, and I doubt any of them were the United States. I also doubt that any of the 11 thousand or so that were made ever made it here, so finding examples of this camera is very difficult without importing them from former Soviet countries.

Today, the Zenit 16 remains a highly sought after model by users and collectors alike. Where most Zenit cameras were rudimentary SLRs without many features to get excited about, the Zenit 16 has a very attractive body with some cool technology inside of it. It might not be apparent everything that’s going on inside the camera when holding it in your hand, but after learning about it’s inner workings and history, would be an excellent addition to any collection.

My Thoughts

If your only experience with a Zenit SLR is one from the Zenit E series, or even the earlier M39 screw mount models, you might think there’s not much to be excited about. Sure, most Zenits are robust cameras that can take a lick and keep on ticking, and of course they support any number of excellent screw mount lenses made in the Soviet Union, Germany, and elsewhere, but most people wouldn’t get too excited if one fell in their lap.

But for those who are familiar with the less common models in the Zenit lineup, there are some gems. You’ve got the leaf shutter Zenit 4, 5, and 6 models that use a version of the Deckel lens mount, there’s the ultra-rare Zenit 7 with it’s unique styling and new bayonet lens mount, and of course there’s the Zenit 18 that was the first Soviet SLR with auto exposure.

Along these same lines is the Zenit 16. Not nearly as rare as those other models, and it still uses the regular M42 screw mount, but the Zenit 16 is an attractive SLR with a unique body design, vertically traveling focal plane shutter, and a coupled CdS exposure meter.

Note: Many sites online incorrectly state that the Zenit 16 has an electronic, or an electronically timed shutter. This is incorrect as the shutter is entirely mechanical and works at every speed with or without power. In the section above, I explain how the shutter timing is determined by a large flywheel connected to the curtains by metal straps. There is nothing electronic about the shutter in the Zenit 16.

The Zenit 16 isn’t rare, as at any given moment there’s going to be a few for sale on eBay, but finding a Zenit 16 in the United States, in working order, for anything remotely close to a good price is difficult. I was after one of these cameras for quite some time before finally giving up and begging my friend Vladislav Kern to borrow one of his. Vlad wasn’t even sure any of his worked, so he went through his stock pile of 16s and finally came across this one that seemed to be OK.

When I first picked up the Zenit 16, I was struck with how much plastic was used in the camera’s construction, yet it was still pretty heavy. Compared to my Zenit E, with each camera’s period correct Helios-44 lenses attached, the Zenit 16 is almost identical in weight 927 grams (including batteries) compared to 920 grams for the older, non plasticky, Zenit.

Up top, the Zenit 16’s minimalist design is in full effect, and likely would cause the first time user to pause, in order to figure out where all the controls are.

On the left is the combined fold out rewind knob and shutter speed dial. The slowest speed is only 1/15, but surprisingly goes up to 1/1000 which is not expected as so many Soviet cameras top out at 1/500.

Atop the large flat surface of the pentaprism is a flash hot shoe. You can’t see it in the previous image as this Zenit 16 still has the plastic shoe protector that would have come with the camera when it was new. Electronic flash synchronization is surprisingly fast, at 1/125 care of the vertically traveling shutter.

Off to the right is the combined film advance lever and a film type dial. There are 6 options to choose from, color indoor and outdoor positive, color indoor and outdoor negative, and black and white positive and negative. The position of this dial has no effect on the meter as it is only a reminder.

The camera’s bottom is quite busy with the rewind release button, battery compartment opening for the three PX625 batteries needed to power the meter, GOST film speed selection dial, and 1/4″ tripod socket. As is the case of most Soviet cameras, the GOST film speed scale is similar to, but not identical to ASA. To get a rough conversion to ASA, simply add 10% to the GOST number and you should be close enough for most films.

The back of the Zenit 16 is more interesting than most of the cameras as it has two things you wouldn’t normally expect to see there, the cable threaded shutter release, and the automatic resetting exposure counter.

Although both the shutter release and exposure counter function as you’d expect from any 1970s SLR, the locations of these controls is definitely strange. Most notably is the shutter release, which is opposite of front shutter releases like those found on Miranda, Topcon, and even some other Soviet SLRs in which pressure on the shutter release goes towards your face, helping to stabilize it. With the Zenit 16 pressing the shutter release presses the camera away from your face, potentially causing body shake and blurred images.

Another oddity of the back of the camera is the large plastic frame around the rectangular eyepiece which is the door release. A small amount of upward movement of this frame releases the lock on the bottom hinged film door, allowing access to the film compartment. Opening the door is easy, almost too easy as I found that the door opened with hardly any force, which if done with film in the camera would have ruined it. This being the only Zenit 16 I’ve ever handled, I cannot say for certain if they’re all like this, but I would be willing to bet they are. Even if yours isn’t as easy to open as this one was, I still recommend placing a line of tape across the top seam of the door to protect it from accidentally opening while out shooting.

Without a doubt, the bottom hinged film door is the most notable thing about the Zenit 16’s film compartment, but once you get past that, the second thing is the lack of a sprocket shaft. The lack of a sprocket shaft on some cameras means that you’ll get unevenly spaced exposures, but the designers of the Zenit 16 came up with some sort of clever system in which the degree of rotation of the take up spool helps maintain evenly spaced exposures. I don’t fully understand how it works, but it does!

Film travels from left to right onto a fixed take up spool. Unlike most take up spools however, there are no slots on the spool for the leader, instead there is a single row of sprockets near the bottom of the spool. When loading film, you must allow the film leader to catch on the sprockets as you wind the camera enough to wrap itself around the spool until it is securely attached.

Although strange, it actually does work quite well but in order to be sure the film is securely attached, you’re going to want to advance the film at least three or four times before closing the door.

The inside of the film door has a metal clip on the left and a large and smooth film pressure plate in the center.

Up front, the Zenit 16 has the standard M42 lens mount. A chrome button near the 8 o’clock position around the lens is the depth of field preview and meter activation switch. Since the Zenit 16 does not support open aperture metering, you must first stop down the lens to your chosen f/stop before an accurate meter reading can be taken.

Also on the front of the camera are two front mounted strap lugs. This location is a bit strange, but serves a purpose as when attaching a neck strap, the camera will hang straight, without tipping forward due to having a lens attached.

The viewfinder in the Zenit 16 is pretty basic, offering a large microprism circle in the center for help with focus, surrounded by a matte finish ground glass circle. The entire viewfinder has a bluish tint which is unexpected to see in an SLR as most are clear, but even more strange is everything seen through the viewfinder takes on a brownish double image. As this is the only Zenit 16 I’ve handled, I am unsure if this is normal or if that something has gone wrong with the one I have. It was difficult to capture through the viewfinder with my smartphone, but while using the Zenit 16, everything I saw was doubled.

Along the bottom edge of the viewfinder is a raised black area which has two red lamps that light up to indicate over and under exposure. The composite image to the left shows both lamps on at the same time so you can see what they look like, but in reality that can never happen. With both lamps off, your image will be properly exposed. As the Zenit 16 lacks any sort of automatic exposure, you must make a corresponding change to the shutter speed or aperture ring to get the two lamps to turn off.

Setting aside the Zenit 16’s very unique appearance, using the camera is rather uneventful, which isn’t a bad thing. I wasn’t particularly a fan of the rear plate shutter release, but at least it was comfortably located where my right thumb could easily find it. Otherwise, this was an easy camera to pick up and start using. This example came to me with an excellent Helios 44M lens mounted, but had it not, I could have used any number of other M42 Soviet, German, or Japanese lenses I had laying around and it would have worked just as well with them.

It is clear, both from reading the history section and while using the camera, that the designers of this camera aimed for an easy to use, but high quality camera, and for the most part, they seemed to have been successful. Then again, the camera sold poorly and wasn’t in production for very long, so maybe I should hold my final opinion until I load in some film…

My Results

For my first roll of film through the Zenit 16, I decided to keep it regional and went with a roll of expired Svema Foto 65 I had picked up a while ago. The film expired in the 1980s and I was told that the film should shoot fine at ASA 50, so that’s what I aimed for. I did attempt to use the meter in the Zenit 16 by setting it to the dot in between GOST 65 and 32, but I didn’t rely on it.

Having shot a number of Helios 44 equipped SLRs, I felt reasonably certain I knew what to expect from the images shot on the Zenit 16. Where the camera might falter was in my reliance on the meter for about half of the roll or some kind of mechanical failure.

As soon as I pulled the negatives from my Paterson tank, I was delighted to see what looked to be a whole roll of properly exposed and focused images, at least to the naked eye.

My use of expired Soviet film from the 1980s appeared to have been a good choice, as the images show a bit more grain than a film rated at ASA 50 would otherwise suggest, and a subtle lack of contrast that give it a bit more of a vintage look than you’d expect from a 1970s SLR. The only real fault I could find with these images were some light leaks that show up in a couple of images. This could have possibly been the result of the door design, but remember I used tape along the top seam of the door to keep it shut. I did not however tape the bottom hinge or the sides, which is where the leak looks like it’s coming from. To be fair though, I did not make any attempt to replace the light seals, as I generally do on most SLRs from this era. As this camera is a loaner, I did not want to mess with someone else’s camera.

The Helios 44M delivered sharp and evenly exposed images across the frame. Corners were sharp and without any obvious vignetting, even in images that show the sky. Interior images show a bit of softness with the lens wide open such as the one of the coffee shop and the image of the children sitting at a table. Also notice in the image with the children, the light from the rear window seems a bit hazy. A quick look through the lens removed from the camera didn’t show any obvious haze, so perhaps this is normal with this film and in that specific lighting.

I generally liked the images I got from the Zenit 16, but I can’t honestly say I was wowed by any of them either. That’s probably more of an issue with the person behind the camera, rather than the camera itself, but that’s a discussion for a different post!

Using the Zenit 16 isn’t difficult, but I did have two complaints with the camera. The first was that I found the viewfinder to be too dark for a mid 70s SLR. I had the same complaint with another Soviet SLR of the era, the Kiev 15 TTL from 1980. It is clear that either the technology or priority of Soviet SLR designers was not the same as those from other Japanese companies of the same era. The viewfinder was sufficiently bright outside, but I definitely struggled indoors.

Also, I could never get used to the position of the rear shutter release. Although it is located within easy reach of my right thumb, it felt unnatural to use. Every time I would get ready to make an exposure, my right index finger would instinctively rise up, expecting to find a shutter release somewhere up top or on the front. Interestingly, on a version of this camera made for the FS-4 Photo Sniper, the shutter release was relocated at the top, suggesting the designers found a reason for it, but for most of the Zenit 16s you’re likely to ever find, it’s on the back.

As I near the end of my review for the Zenit 16, I feel a sense of confliction. On one hand, learning about the technology inside of the camera and my fondness of it’s design, I feel like I should be kinder to this camera, but it’s rather uneventful feature set, dark viewfinder, and strange location for a shutter release make me less thrilled with it.

Perhaps though, that is the best recommendation I can make about the Zenit 16, it is a camera you need to experience for yourself to come to a conclusion on. Where many Zenits are uneventfully boring, the Zenit 16 stands out and begs you to give it a try. Perhaps after picking one up, you’ll come to the same confliction as I, but at least it made you think and for that I think it’s a winner. Thanks again to Vlad Kern for letting me borrow this camera, but dammit Vlad, I am getting tired of borrowing cameras from you that I later want to go out and buy for myself!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Zenit_16

http://www.sovietcams.com/indexf4bc.html

https://kosmofoto.com/2020/03/the-zenit-16-the-russian-revolution-that-never-quite-happened/

http://www.zenitcamera.com/archive/zenit-16/index.html

http://ussrphoto.com/wiki/default.asp?WikiCatID=69&ParentID=1&ContentID=374