This is a KW Praktiflex, a 35mm SLR camera built by Kamera-Werkstätten AG in Dresden-Niedersedlitz, (East) Germany between the years of 1939 and 1949. The Praktiflex was originally designed by Alois Hoheisel and was the first new camera built by KW after ownership of the company was transferred to Charles Noble. This particular camera is a later “second generation” variant built in 1947, which had received several upgrades by new designer Siegfried Böhm. All early Praktiflexes were simple, yet rugged SLRs with a fixed waist level viewfinder, focal plane shutter, and an interchangeable 40mm lens mount.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 5cm f/3.5 Carl Zeiss Jena Tessar coated 4-elements

Lens Mount: M40 Screw Mount

Focus: 0.7 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Fixed SLR Waist Level Finder

Shutter: Cloth Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/25 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 694 grams (w/ lens), 623 grams (body only)

Manual (similar model): https://www.butkus.org/chinon/praktica/praktiflex_fx/praktiflex_fx.htm

How these ratings work |

The KW Praktiflex is a historically significant camera and one worth owning in any collection. For a camera originally designed prior to WWII, it is still an easy to use camera today. When found in working condition with one of the many excellent lenses made for it, this is a camera that can produce photographs that rival those made decades later. It’s simple use and construction mean that many are still found in working condition today, and are still a lot of fun to use. Highly recommended. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for historical significance, first cameras with quick return mirror and common ergonomics | ||||||

| Final Score | 14.0 | ||||||

KW was founded in Dresden, Germany in 1919 by Paul Guthe and a Swiss businessman named Benno Thorsch as Kamera-Werkstätten Guthe & Thorsch. Guthe had previous experience in camera manufacturing, owning another camera factory in the Dresden area that he founded a few years earlier in 1915.

KW’s first product was a folding camera called the Patent Etui. It had an extremely slim and compact body that was quite a bit smaller than comparable cameras of the time. The word “etui” in German translates to “case” in English. There were versions made for 6.5cm x 9cm sheet film and some that used 9cm x 12cm film. The Patent Etui had an innovative and unique design that was unlike any other camera made at the time, or even in the years that would follow. Innovation would become a hallmark of KW’s legacy, setting a standard for new and unique designs and features in many of their models to come.

The Patent Etui was in production throughout the 1920s at a time when the German economy was very weak due to the outcome of World War I. Many German companies would either collapse or merge with other companies during the 1920s. In 1926, four Dresden area companies would all merge together to form one single company that would be called Zeiss-Ikon. But not KW, they were one of the few Dresden optics companies that saw great success. So much so that in 1928, KW moved from it’s original location in Niedersedlitz to a larger facility in Dresden, right down the street from Zeiss-Ikon’s factory. KW employed at least 150 employees and the company’s output at this time was around 100 cameras a day.

In 1931, KW released another innovative camera with an all new design called the Pilot Reflex. This new camera was a folding Twin Lens Reflex design that took 3cm x 4cm images on “Vest Pocket” 127 roll film. The Pilot Reflex combined the best features of a TLR like the Rolleiflex and a folding camera that when collapsed was much smaller and portable.

Note: A large amount of the information from the next few paragraphs comes from an excellent essay on KW’s history written by T. Rand Collins MD on his blog, “Through a Vintage Lens”. I will do my best to paraphrase the relevant facts here in my own way without plagiarizing the original author’s work, while still giving him full credit for the research.

At the time of KW’s greatest success, Paul Guthe and Benno Thorsch who were both Jewish, started to feel the pressure of anti-Jewish treatment in Germany and in 1938, would flee the country. Guthe was the first to leave, selling his shares in the company to Thorsch. Very little is known about what happened to Paul Guthe after he left Germany, but Benno Thorsch’s story on the other hand, is quite fascinating.

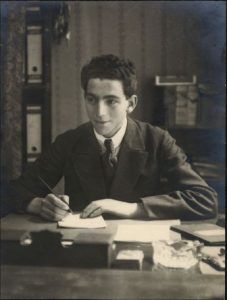

Before leaving Germany, Benno Thorsch befriended a German born American businessman named Charles A. Noble (born Karl Adolf Spanknöbel) who owned a failing photo-finishing company in Detroit where his wife worked. Thorsch would negotiate a mutually agreeable trade of KW for Noble’s company back in the United States. Benno Thorsch quickly left for America to run his new business while Charles Noble’s family moved to Germany to take over KW. Together with his son John, in 1939 Charles would rename the company to Kamera-Werkstätten Charles A. Noble.

Benno Thorsch would revive the Noble’s struggling film finishing business in Detroit, but would ultimately relocate out west and in 1944 would open the Studio City Camera Exchange on Ventura Boulevard in North Hollywood, CA. Benno would run the business with his son Bennie, and eventual grandson Ronald for 62 years until it closed in 2006. Benno Thorsch would live a long life, eventually passing away in a retirement home in 2003 at the age of 105.

The Noble’s story however, went in a different direction. Upon resuming business operations in 1939, Charles Noble felt that 35mm Single Lens Reflex cameras were the way of the future, so he hired German engineer Alois Hoheisel to help design KW’s first 35mm SLR camera, the Praktiflex.

The Praktiflex made it’s debut at the 1939 Leipzig Fair and would generate excitement almost immediately. Featuring a fixed waist level finder, an interchangeable 40mm lens mount, and the world’s first quick return reflex mirror, demand for the new Praktiflex was so great, that the company had to quickly relocate into a former candy factory in Niedersedlitz.

The Praktiflex was very popular, but also very basic, so in 1941 an updated model called the Praktiflex II was shown at that year’s Leipzig Fair. The new camera had a wider selection of shutter speeds from 1 second all the way to 1/1000, a self-timer, and an upgraded flash synchronization system. Due to cost overruns and KW’s commitment to the German war effort, the Praktiflex II was never completed.

Unlike many other manufacturing companies in Germany during World War II, it appears that KW was allowed to continue making cameras throughout the war as there exist cameras made between 1940 and February 1945. In fact, at least one variant of the original Praktiflex was made for the German military. Military issue Praktiflexes were engraved with “M 309” on the bodies and all lenses associated with it. Whether KW also produced other, non-optics products for the German war effort is unknown.

In four separate bombing raids on February 13th, 14th, and 15th, 1945, Allied bombers unleashed an unprecedented attack on Dresden, likely because of it’s manufacturing and transportation capacity. 722 bombers from the British Royal Air Force and 527 from the United States Army Air Forces dropped a combined 3900 tons of bombs and incendiary devices on the city. The “shock and awe” firestorm resulted in the complete destruction of over 6.5 square kilometers of the city’s center and a widely disputed number of deaths.

The KW factory was spared total destruction likely because of it’s location in nearby Niedersedlitz, as opposed to the city center like most other optics companies of the time. Production of the prewar Praktiflex would resume after the Dresden bombings for at least another year.

Dresden is located in what would become Soviet controlled East Germany. Upon occupation of Soviet forces in Dresden, KW would become a state owned entity known as VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz. The abbreviation VEB stands for Volkseigener Betrieb which translates to ‘Publicly Owned Operation’ in English and was the main legal form of industrial enterprise in East Germany from the late 1940s until the early 1960s.

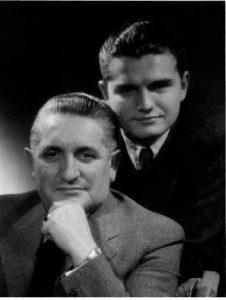

Initially, Charles and John Noble maintained control over their company after the war, but after a trip to re-negotiate a deal with Zeiss to produce lenses for KW, both Charles and John Noble were arrested under unfounded suspicions of espionage and sent to prison camps in the Soviet Gulag system. The conditions in the forced labor camps were abysmal. Starvation and executions were common practice, and both Nobles relied on their religious background to stay alive.

Charles and John were kept together in the same prison camp until 1950 when John Noble, who was 26 at the time, was given a 15 year sentence and sent to a variety of different Soviet prison camps, one of which was the Soviet Special Camp No. 2 which was formerly the Nazi Buchenwald concentration camp. John would eventually wind up in town called Vorkuta in northern Siberia where he mined coal with over 100,000 other prisoners.

In 1952, Charles Noble would be released from prison, never to return to KW or Dresden again. He would at first live with relatives in West Germany, but eventually made his way back to the United States where he worked as an adviser to the photography department of General Motors. John would remain a prisoner until 1955 after successfully getting word back to his family, who then reached out to the United States Government and negotiated his release.

With the Nobles out of the way, KW was under control of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD) who set an annual production goal of 50,000 cameras, a number that was unattainable largely due to the hand crafted precision parts required for their cameras.

In January 1946, SMAD would transfer Siegfried Böhm from the Zeiss-Ikon factory in Dresden to KW in an effort to help improve the speed and efficiency of it’s output so they could meet their lofty goals. Böhm was a German born technical draftsman who in 1939 at the age of 18, went to work as a technician for Zeiss-Ikon AG in Dresden. There, he learned how to design and build 35mm cameras under Zeiss leadership. In 1945, Böhm would return to Zeiss and continued to develop his efficient methods at improving on the pre-war designs that the company had resumed making.

In September 1947, a second generation Praktiflex was released with several of Böhm’s changes which simplified the Praktiflex’s design in an effort to produce the cameras faster and to meet the SMAD’s ambitious goals. The most notable change to the camera was the quick return reflex mirror was replaced with a simpler mirror that remained in the up position after firing the shutter. Additional changes were made to the shutter release which was moved from the top plate to the front of the camera, the rewind and advance knobs decreased in size, and the manner in which the camera back attached was simplified.

Early second generation Praktiflexes retained the M40 screw mount, but later in October 1948, models with a larger M42 screw mount were produced concurrently with M40 models. The larger M42 mount allowed for wider angle and faster lenses which required a larger opening into the camera’s mirror box.

Prewar Praktiflexes were exported out of Germany into the United States, but I was unable to find any information about the second generation models in any of the American publications I had access to while researching this article. In the ad to the left from a 1941 New York Fotoshop catalog, the Praktiflex was listed with prices ranging from $68 to $145 depending on lens. These prices, when adjusted for inflation, compare to $1250 – $2650 today, making it quite an expensive camera.

In October 1949, the entire lineup of Praktiflex cameras would be discontinued and replaced by a similar model called the Praktica which retained the same body, fixed waist level viewfinder, and removable back. The shutter would be upgraded to allow for slower speeds down to 1/2 second, and the front lens plate would be revised.

The Praktica was an immediate success, helping to reestablish KW as a premiere maker of German built 35mm cameras. The Praktica name was used on a huge variety of 35mm SLR cameras over the course of the next several decades.

With the release of the Praktica, there was no need to continue making the Praktiflex, but in 1953 the name was used again as the Praktiflex FX on exported versions of the Praktica FX.

Estimating the total production of Praktiflex cameras (excluding the FX) is difficult as accurate wartime records were not kept. In addition, so many variations of parts were mixed and matched with overlapping features and inconsistent serial numbers, that coming up with an exact number is almost impossible. The best estimate of total combined 1st and 2nd generation Praktiflexes is between 55,000 and 60,000 units.

VEB Kamera-Werkstaetten Niedersedlitz would continue to exist, producing Praktica and their professional level Praktina cameras until 1964, at which time the company was absorbed into VEB Pentacon Dresden. Pentacon would eventually claim every other Dresden area camera manufacturer including Zeiss-Ikon, Ihagee, Altissa, Belca, Welta, Certo, Meyer-Gorlitz, and many others. It would continue on as Dresden’s only camera manufacturer for the next several decades, discontinuing most of the models of the companies it absorbed with the exception of the M42 mount Praktica SLR. The Praktica series remained in production until the late 1990s eventually adopting most modern features like electronic shutters and auto exposure.

Today, the Praktiflex is an uncommon, but highly collectible camera. It was historically significant in that it had the world’s first quick (not instant) return reflex mirror, it was affordable, easy to use, and generally reliable. In addition, there are tons of variants of the camera that allow for multiples to be collected with small variations. Some Praktiflexes left the factory painted black instead of chromed, and even came with red, blue, and brown body coverings. The Praktiflex has appeal for almost anyone who collects cameras.

My Thoughts

When I reviewed the KW Praktina FX in November 2017, I learned a great deal about KW’s history and for a short while I became obsessed with other KW cameras. I searched high and low for Patent-Etuis, Pilot SLRs, and Reflex-Boxes. I learned that when buying each of those cameras, they come in two varieties, broken and expensive. So instead, I turned my attention to a more attainable camera, the Praktiflex. After all, it was essentially the predecessor to the Praktica, so it’s historically significant, right?

My first Praktiflex was an early 1st generation model that was in very rough condition and had a dead shutter. I made a valiant attempt to get it working, but it was too far gone.

Then, a couple of months later, while looking through a lot of old cameras for sale from KEH, I noticed not one, but two Praktiflexes in the lot and I took a chance on it. When the box arrived, there was a later Praktiflex FX with the M42 mount and a second generation Praktiflex with a beautiful Zeiss Tessar 3.5 attached.

I wasn’t as interested in the FX as it’s essentially a Praktica with a waist level finder, and it’s Westanar lens had issues with the diaphragm, so I turned my attention to the second generation Praktiflex and to my delight, it worked!

The Praktiflex feels solid in my hands and is surprisingly heavy, especially considering there’s no pentaprism, which can often add a bit of heft to an SLR. The Zeiss Tessar lens is quite small. A combination of the 40mm lens mount plus that Tessars generally are small anyway results in a weight of only 71 grams for the lens.

Looking down upon the top plate, there’s not much to see. Most of the features of the entire Praktiflex lineup went unchanged from it’s introduction in 1939 until the release of the FX in 1952, which is notable considering the only other German made 35mm SLR was the Exakta and it’s control layout does not resemble a modern day SLR one bit.

The curiously small rewind knob is on the left and was a casualty of cost cutting when the second generation models were released in 1947. There’s quite a bit of blank space around the knob making it look sorely out of place. In the center is the fixed waist level viewfinder. Unlike most cameras like the Exakta, Miranda, or Nikon, the finder is not removable. Pentaprism SLRs didn’t appear until 1948 with the release of the Rectaflex, and it wouldn’t be until the Exakta Varex/VX from 1950 that interchangeable pentaprisms would hit the market.

Like most waist level finders, lifting the hood reveals an inverted view through the lens. Everything you see is backwards, so if you want to compose an image to the left, you actually need to move it to the right. The focusing screen on all Praktiflexes is a condenser type ground glass. No models ever came with a Fresnel type screen or with any focus aides like a microprism collar or split image rangefinder. For precision work, a small magnifying glass tucked under the lid can swing out to magnify the center of the image. For fast action shots, the center part of the front lid can fold which creates a “sports finder” when looked at through a small hole in the back of the hood frame.

To the right of the viewfinder is the shutter speed indicator with speeds 1/25 through 1/500 plus Bulb. It would not be until the release of the FX model that speeds down to 1/2 were supported, but no Praktiflex ever went above 1/500. To the right of the shutter speed selector is a small rewind release button, and then the combined film advance knob and manually resetting exposure counter.

Flip the camera to it’s underside and you see a 3/8″ tripod socket, surrounded by a large swath of body covering, and nothing else. The larger tripod socket means you cannot mount this camera on a modern tripod without an adapter.

Film is loaded by first releasing a latch on the camera’s left side, which allows the entire back of the camera to be removed. Inside is an ordinary looking film compartment. Film transport is from left to right onto a single slotted, non removable take up spool. The spool rotates clockwise when the film is advanced.

The lens mount is a 40mm screw mount which was unique to the Praktiflex. Neither Leica Thread Mount nor later M42 lenses could be used, and I know of no adapters for this camera. If you ever come across a Praktiflex body only, you’ll likely have a hard time finding a correct lens for it.

The shutter release on the second generation Praktiflex is near the 10 o’clock position around the lens mount and has a threaded cable release socket. This was a change from the first generation Praktiflex which had it on the top plate. The later FX model retained the shutter release in this position as would generations of Prakticas made in the decades that would follow.

In later years, Praktica cameras developed a reputation as cheap, soulless cameras that were poorly made and not very much fun to shoot. Although the Praktiflex is the predecessor to the Praktica, it in no way is soulless or boring. Yes, the camera is simple, but complex features don’t necessarily make a camera better.

The controls are exactly where you expect them to be, the viewfinder is large and bright enough to be used in all but the darkest scenes, and the front mounted shutter release allows for a smooth motion when firing the camera without introducing too much shake, which means you can stabilize the camera against your chest and shoot the camera at it’s slowest speed without risking blurred photos.

My Results

Although the Praktiflex seemed to be in good operating condition, the slowest 1/25 speed seemed too slow to the naked eye and I didn’t have faith in the fastest 1/500 speed either, so I decided to play it safe and loaded in some 100 speed film. For that, I had a single expired roll of Kodak 100 color film. Although I had no idea how old the film actually was, the cassette matched that of Kodak Gold 100 from the 1990s. Assuming the shutter on the camera was probably a bit slow, I shot it like a 100 speed film thinking any slowness in the shutter might actually help the expired film.

I was very pleased with my choice of expired Kodak 100 speed film on the bright and sunny day I shot most of the roll. The film took on somewhat of a warmer tone and despite it’s age, grain was minimal. The Tessar lens was predictably sharp across the entire frame, and the post war lens coating did not show any signs of flare and provided a nice amount of contrast.

More notably than the terrific images I got, was the camera itself. To be honest, prior to shooting the Praktiflex, I didn’t really have that high of expectations for it. I’ve shot East German SLRs before, and I’ve shot many with waist level finders, but the experience was more than the sum of it’s parts.

The Zeiss Tessar formula has existed since 1902 and is perhaps the most famous and most copied lens formula ever so no matter what camera you are shooting, when the lens is a Zeiss Tessar, there’s a certain level of quality that you can expect, and most of the time, are rewarded with and my experience with the KW Praktiflex was no different.

For starters, the camera is very basic. The shutter is limited to five speeds from 1/25 to 1/500 and this particular example had issues with the slowest and fastest speeds, so I just left it at 1/100 for the entire roll. I compensated exposure only with the iris. I needed to maximize my chances at getting good images by shooting outdoors in bright lighting, so that allowed me to easily compose my images in the viewfinder. Although I did use the magnifying glass a couple of times, I found that it wasn’t really necessary most of the time.

I recently reviewed the Leica Model A and championed that camera for it’s quick operation due to it’s basic feature set. In some ways, the Praktiflex is like an SLR version of that same camera in the sense that there’s not much to it. This is a simple camera that if you shoot it to it’s strengths, you are rewarded with quick and easy shots where you can spend most of your time on thinking about your composition rather than the technicalities of the camera.

The build quality on these isn’t as good as other top tier German cameras so finding one in good working condition today might be tricky, but it’s worth it. I really enjoyed my time with the Praktiflex and although the other two examples I had didn’t work, that likely won’t prevent me from taking a chance on another if the price is right!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Praktiflex

https://www.dresdner-kameras.de/praktiflex/praktiflex.html

http://www.praktica-collector.de/Praktiflex_SLR.htm

https://kosmofoto.com/2018/09/praktiflex-fx-review/

http://www.earlyphotography.co.uk/site/entry_C565.html

http://forum.mflenses.com/praktiflex-1st-generation-from-1940-t33280.html

Another great review! I used to frequent Studio City Camera on a regular basis. There was a pretty amazing display of rare cameras in the sore windows. Most of them were starting to show the effects of exposure to strong California sunlight. I was out of the country when they closed, and don’t know what happened-some neat stuff even if faded

I have this camera except mine has the Victar f2.9 lens. I have yet to run a roll through it, but I’ve bought a several rolls of Fujicolor c200 so I can test some of the cameras in my collection. This camera is on my short list of shooting with soon.

The Victar was an early equivalent of what we call today a “kit lens” as it was included as the base lens on many cheap cameras. It is not a bad lens by any means, but definitely has some flaws compared to the more well-regarded Tessars and Xenars of the day.

I’m searching lots of information about Praktiflex because I also got captured by KW’s magic since I went back again to film photo with my Praktica. Reading your post, I wonder why you did not use the Victar from your first version to the second, operative version, instead of the tessar, because they are interchangeable.

(On the other side, I’d like to tell you I could get a first generation Praktiflex with a Xenon and getting pictures with it is one of my best experiences)