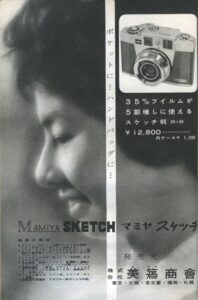

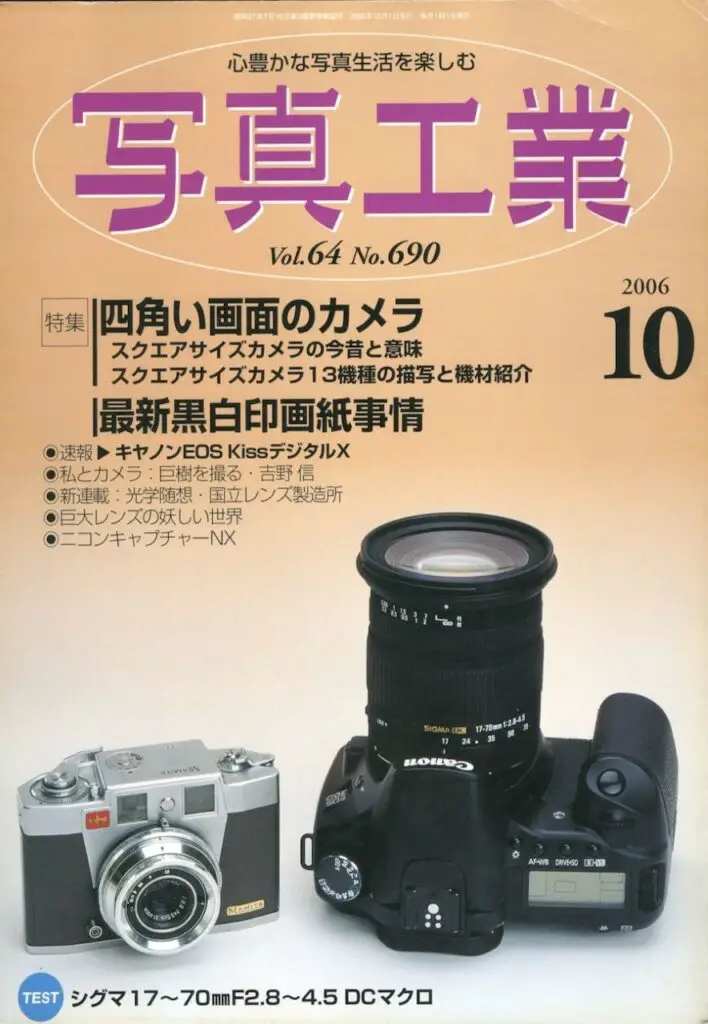

This is a Mamiya Sketch, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by Mamiya Optical Co., Ltd. in Tokyo, Japan in 1959. The Sketch was the first ever Japanese camera to shoot 24mm x 24mm images on regular 35mm film, a format that would never gain popularity among Japanese photographers. The Sketch was developed at the same time as the first Olympus Pen and was likely seen as an alternative to that camera’s half frame 18mm x 24mm images. It is a high quality camera with a good 4-element 3.5cm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor lens and a coupled coincident image rangefinder. Despite Mamiya’s excellent reputation as a camera maker, and the Sketch often being promoted in advertisements by popular Japanese actress Keiko Kishi, the camera was not successful and very few were ever built.

Film Type: 135 (35mm), 24mm x 24mm Square Exposures

Lens: 3.5 cm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor coated 4-elements in 3-groups

Focus: 0.6 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Copal SV Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Cold shoe and M and X Flash Sync

Other Features: Self-Timer

Weight: 436 grams

Manual (in Japanese): https://mikeeckman.com/media/MamiyaSketchManual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Mamiya Sketch is a very interesting and historically significant camera that sold poorly and is difficult to find today. It was the first ever, and one of only a small handful of 35mm cameras that made 24mm x 24mm images. It has an excellent Mamiya-Sekor semi-wide angle lens, a capable Copal leaf shutter, and a combined image coupled rangefinder. The camera is very compact and is much smaller than most other full frame Japanese cameras of the era and is a lot of fun to shoot, assuming you can find one. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 20% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.8 | ||||||

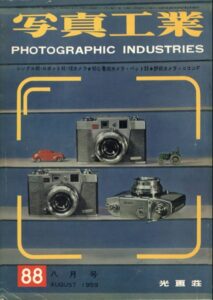

History

Of all the camera makers from the 20th century, if there was one that I’d pick to be the most prolific, I would have to say Mamiya. Sure, brands like Zeiss and Leitz pioneered 35mm cameras and cemented Germany as the benchmark for quality for the better part of a century, and yeah, Nikon and Canon dominated the second half of the century raising the bar for quality, mass production, and innovation to a degree that even the Germans couldn’t match, but then there’s Mamiya who pretty much tried everything. Before I prepare for some WTF comments in this article, let me remind you of a few highlights:

Of all the camera makers from the 20th century, if there was one that I’d pick to be the most prolific, I would have to say Mamiya. Sure, brands like Zeiss and Leitz pioneered 35mm cameras and cemented Germany as the benchmark for quality for the better part of a century, and yeah, Nikon and Canon dominated the second half of the century raising the bar for quality, mass production, and innovation to a degree that even the Germans couldn’t match, but then there’s Mamiya who pretty much tried everything. Before I prepare for some WTF comments in this article, let me remind you of a few highlights:

- Formed in 1940, first product was the Mamiya Six, the first camera to focus with a moving film plane rather than with a lens helix or rotating elements

- First Japanese company to resume making cameras after WWII, January 1946

- First Japanese 35mm camera with interchangeable magazine backs, Mamiya Magazine

- First Twin Lens Reflex with interchangeable lenses, Mamiya C-Series

- First Japanese camera to shoot 24mm x 24mm images, Mamiya Sketch

The Mamiya Auto XTL used it’s own bayonet lens mount that was used on only one other camera. - Mamiya cameras were badged under a huge number of other brands, Nikon, Canon, Ricoh, Sears (Tower), Argus, Polaroid, Revue, Porst, Bell & Howell, Reflexa, Rank, Mansfield, Honeywell, and others

- Produced cameras using a variety of film formats, 16mm, 35mm, 120, Rapid, Polaroid Instant Film

- Produced 35mm and 120 cameras in nearly every aspect ratio, full frame, half frame, square frame, 4.5cm x 6cm, 6cm x 6cm, 6cm x 7cm, and 6cm x 9cm

- Produced cameras with the most number of unique lens mounts, Exakta Bayonet, M42 Universal Screw, M42 SX Screw, Prismat PH Bayonet, Nikon F Bayonet, Argus SLR Bayonet, Mamiya Auto XTL Bayonet, Mamiya CS Bayonet, and Mamiya ZE Bayonet

The above is just a short summary of vast number of projects that Mamiya has been involved in. From the outside, it seemed like Mamiya was a company without a clear direction. Sure, they produced some of the most sought after professional TLR and medium format SLRs of the era, but what was up with all the constantly changing lens mounts, and why where they so willing to lend their designs to other brands? Was it a result of a rotating door of management who kept coming in with different priorities, or was it that they had a hyperactive R&D department who struggled to maintain their focus on a single direction?

Whatever the reason, one thing that’s for certain is when Mamiya did make something, it was usually pretty good. Originally just a camera maker, in 1947, Mamiya started producing their own lenses at a local factory called in nearby Setagaya. In 1950, the factory was incorporated as Setagaya Kōki K.K. producing lenses and shutters exclusively for Mamiya, then in 1963 the company was completely merged into Mamiya resulting in a joint Mamiya-Sekor camera and lens making duo.

If we operate under the assumption that Mamiya had a very active R&D department, in 1958, the company caught onto something that was brewing at a couple other Japanese camera makers. The state of the film industry in postwar Japan was still very difficult. As a 21st century collector, it is easy to glamorize the 1950s as this wonderful “Golden Era” of cameras where some of the best Nikon and Canon rangefinders, Asahi Pentax SLRs, and Minolta TLRs dominated every camera store and were being used by everyone.

The reality is, a huge amount of Japan’s camera production was sold outside of Japan for the purpose of bringing money into the country to help rebuild the economy. Japan didn’t just lose the war, their economy was decimated, their infrastructure was destroyed, their government and military were demoted and replaced with one installed by the American government, and with tensions still very high in the region with China, Korea, and the Soviet Union’s interest in the area, supplies for everyday items were difficult and expensive to acquire.

At the time, photographic film was a luxury that few could afford in large quantities. When someone did buy film, it was often for smaller cameras that used 16mm or other types of subminiature cameras. This helps partially explain the popularity of all those “Hit style” cameras like the Mycro and Gemflex cameras. Although these cameras are seen as toy cameras today, for those without a lot of money, they were the most affordable options.

Things started to improve by the late 1950s, but buying and developing a single roll of 35mm was still something that needed to be done in moderation. In the 1958 ad to the left for Sakura color film, a single 12-exposure roll of 35mm film was ¥400 with development extra. According to a report by the National Tax Agency, the average annual salary in 1958 Japan for private sector wage workers was ¥223,100. Assuming a 40 hour work week, that comes to an hourly wage of roughly ¥107 per hour. This means that in order for an average wage worker to buy a single 12 exposure roll of 35mm film, it would cost him or hear nearly half a day’s salary.

If we extrapolate that out to modern terms, in the United States today, some states have established a minimum wage of $15 hour, and if someone working at that rate had to buy something that cost half a day’s salary, we’re talking about a $60 price tag. Yes, I know I am making some pretty big leaps here as the minimum wage for Americans in 2023 is not the same as a worker in 1958 Japan, but at the very least, it still proves that buying a single roll of film back then was very expensive.

As a result, manufacturers got to work developing cameras that could fit more exposures on a roll of film by shrinking the exposed image size. At Olympus, a young designer named Yoshihisa Maitani got to work on an all new camera called the Olympus 18 and at Konishiroku, a version of the popular Konica III rangefinder was produced that could expose images half the size of a normal 24mm x 36nnm exposure.

These two cameras would be released in 1959 as the Olympus Pen and Konica III M. The Konica III M offered both full frame and half frame capability via a half frame mask and a double wind film advance in which only a single wind was required for half frames.

At the same time, Mamiya got to work on their own half-frame camera. Like the one being designed at Olympus, the new camera was to be compact and would offer additional economy to it’s user by fitting more exposures onto a roll of film than a traditional 35mm camera could.

Somewhere along the way however, plans changed.

One major difference between Mamiya and Olympus is that by the late 1950s, Mamiya had a pretty strong export business to the United States. A large number of Mamiya’s cameras were distributed in the US directly by Mamiya, whereas Olympus was still a relative newcomer. SCOPUS, a division of Berkey Photo began importing cameras like the Olympus 35 around 1956-57 but prior to that, the brand was not well known here. Mamiya, on the other hand, had been a favorite of Post eXchange sales to US service men and women since the late 1940s.

This had the side effect of Mamiya catering to American tastes with many of their cameras, both in design, and functionality. Around the time both Olympus and Mamiya were working on new half frame cameras, word got to Mamiya that the Americans had no interest in a half frame camera. That it would never sell here and if Mamiya ever had a chance for the camera to succeed, it needed to make larger images.

For reasons I could never quite understand, Mamiya decided to change the camera from producing 18mm x 24mm half frame images, to 24mm x 24mm square images. It wasn’t a completely off the wall idea, as there was historical precedence set by the highly successful Berning Robot series and Zeiss-Ikon Tenax I and II which both shot 24mm x 24mm square images. Another possible explanation was that Mamiya was already familiar with square images with their successful 6cm x 6cm medium format TLRs and thought that they could take the square image concept and apply it to smaller 35mm cameras. Whichever of those is true (or perhaps none), the company finished the camera and gave it the name, Mamiya Sketch.

What little information is online about the Mamiya Sketch suggests it was only produced in 1959, but in the short article to the left from the July/August 1959 issue of CamerArt Magazine, it suggests that Mamiya completed a trial in 1958. Whether this “trial” means the camera was available to be purchased in 1958 is unclear, but it almost certainly suggests early copies of the camera were being made then.

When it was officially released in May 1959, the Mamiya Sketch immediately competed with the half frame Olympus Pen and to a lesser degree, the Konica III M as that was a significantly more expensive camera.

The Sketch was advertised for ¥12,800 and a leather case for ¥1,200 more. This price was more than double that of the Pen’s target ¥6,000 price, but Mamiya likely justified that with it’s larger images, coupled rangefinder, and more modern design.

Although there is no evidence the Mamiya Sketch was exported to the United States, we know that the Olympus Pen carried a retail price of $35, and if in Japan the Sketch was slightly more than double the price, we can assume that a starting point for the Sketch had it been sold here would be around $70. Using the US Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Inflation Calculator, the price today of a similarly priced camera after inflation would be comparable to about $725 today.

According to the user manual and some information online, a microscope adapter was available for the sketch which would allow the user to attach the front of the camera to the eyepiece of “any microscope”. Exactly how this worked is unclear as the one image to the right is very low resolution, I have never seen a photo of the adapter itself, and the manual does not describe it any detail.

The Sketch was produced in very small numbers and was discontinued about a year after it was released. Within it’s short life, at least two versions are known to exist with the only difference being the color of the logo on the front of the camera. Most versions are red, but some have been found in black. Apart from the color, it is not known if there were other changes to the camera.

Although a failure with consumers, Mamiya was not wrong to consider a camera that shot smaller than 24mm x 36mm images. After the release of the Olympus Pen, nearly every other Japanese camera maker would produce half frame versions like the Nikon S3M, Canon Dial, Ricoh Auto Half, Fujica Drive and many others. Some half frame SLRs were created as well, such as the Olympus Pen F and Konica Auto-Reflex that could shoot both half and full frame on the same roll of film.

I can’t help but wonder what the original half-frame version of the Sketch might have have looked like had it been completed. The failure of the Sketch wasn’t in the quality or the reputation of the company who made it as Mamiya was a respected maker, and the Sketch would prove to be a well built and capable camera, it was just that if someone was looking to save money on film, they could save even more on one that shot 18mm wide images instead of 24mm.

Strangely, Mamiya would never make a second attempt with the Sketch formula. They wouldn’t even release a proper half frame 35mm camera until the Mamiya Myrapid from 1967 which used a variation of 35mm film called Rapid film which involved a cassette to cassette film transport.

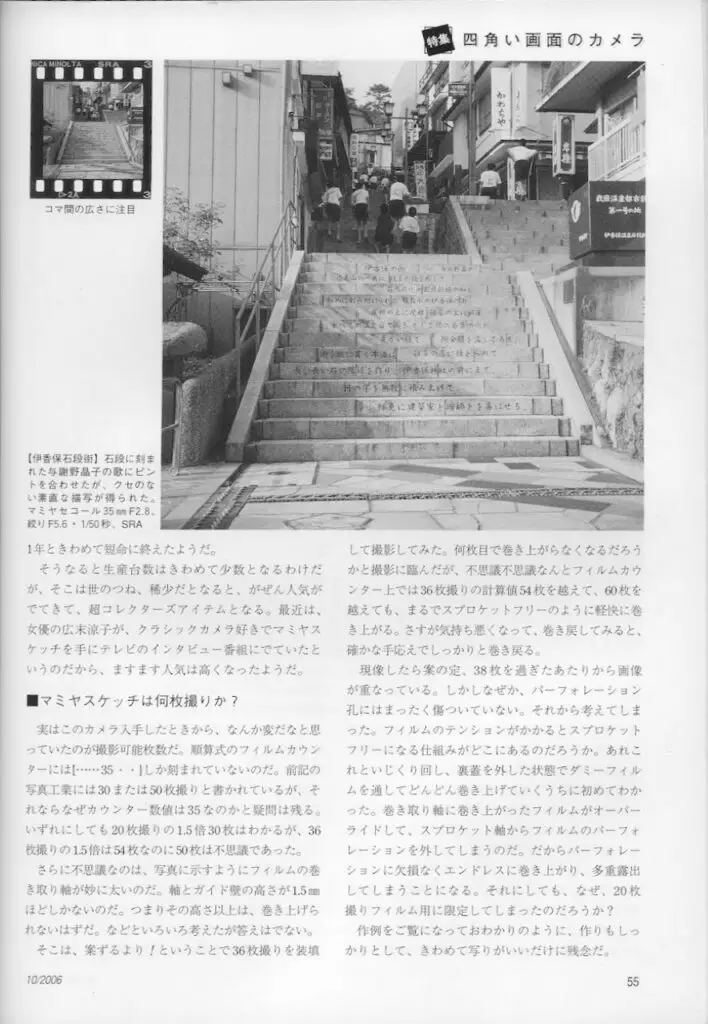

In October 2006, Shashin Kogyo published a retrospective article written by Yasuo Inoue about the Mamiya Sketch. The article doesn’t go into any great history, but rather covers the features of the camera and ponders questions like why the camera was limited to only 20 exposure cassettes. Strangely, it suggests the front lens can be easily removed for attachment to a microscope. I have never found an easy way to remove the lens without using a lens spanner and other tools. Images scanned and courtesy, usedcameracameracamera.com.

Today, obscure and historically significant cameras like the Mamiya Sketch are highly desirable by collectors because of their rarity and that they offered a feature that was not common among other brands. Adding to appeal of this camera is that it was actually a well made camera, with Mamiya’s typical high build quality and excellent Sekor lenses. I found no information about how many of these cameras were produced, but the number must be very small as these rarely show up for sale, and when they do, asking prices are usually quite high. If you are in the market for a camera with an unusual combination of features, that is very compact, capable, and has a great lens, then this is one to keep on your radar, just be sure to save up!

My Thoughts

When I first started collecting cameras and researching them for articles on this site, I remember how often I’d come across something new and think to myself, “Wow, that looks cool, I need one!” This happened a huge number of times to me, but as the years went on, the number of cameras I had never seen before got smaller and smaller and the number of times I was dumbstruck by something new became fewer and farther between.

But even now, after nearly 10 years of collecting and researching, I still do encounter models I had never seen or heard of before. One such incident was in the summer of 2022 when I saw a really tiny camera I didn’t recognize for sale in a shop for a reasonable price. It was clear by the name on the lens and top plate that this was some kind of Mamiya camera, but the exact model didn’t appear anywhere on it. I bought the camera, not even knowing what it was, but it’s small size suggested it was probably some kind of obscure half-frame model.

As it would turn out, I got the obscure part right, but this was not half-frame camera, it turned out to be the Sketch, Japan’s first, and one of a very few models to shoot 24mm x 24mm images on 35mm film. As I would come to find out, the Sketch is very uncommon and highly sought after by collectors. The first time I picked it up, I marveled at how small it was.

The Sketch is smaller than both a Berning Robot Junior and a Canon Dial. The camera in my collection that it most closely resembles in size is the Bolsey B2, but only in width and height as the Bolsey is thicker front to back. On the scale, it still has a substantial weight of 436 grams, which for it’s compact size, gives a feeling of density that a tiny camera might not have.

The camera’s build quality feels very good, as does most late 1950’s Japanese cameras. The satin chrome finish is very smooth and deep, without the shiny feel of a lesser plating. The gray leatherette body covering is still in good condition without any peeling and has just the right texture to look like something more luxurious, while still offering an acceptable amount of grip.

Up top, the Sketch looks like most other late 50s rangefinder cameras, just smaller. Starting from the left is the fold out rewind crank. To save space, the crank is connected to an inner shaft and folds out of the way when not used. It is not part of a larger knob like many other 35mm cameras are. In the center, next to the engraved Mamiya logo, is a film reminder disc with ASA speeds 50 to 400 for black and white film, and 10 to 32 for color film.

On the right side of the camera is a small chrome shutter release button and combined film advance lever and manually resetting exposure counter. The shutter release is not threaded for a cable release, and is rather small, squished up against the side of the stepped plate that houses the rangefinder. The exposure counter is additive, showing the number of exposures taken. Unlike a half frame 35mm camera that goes as high as 72, the highest number is 37 which is about the number of exposures you’d get from a 24 exposure roll of film shooting 24mm wide images. I was unable to find a user manual for the Sketch, but I found information suggesting that the user manual advises against using a 36 exposure roll of film in the camera as the take up spool cannot hold that long of a piece of film. In order to reset the exposure counter, press down on the knurled edges with your finger and turn it in the direction of an arrow on the counter.

Flip the camera over, and on the base is a rewind release dial, a folding lock for the film compartment, and a 1/4″ tripod socket. To rewind film, you need to rotate a dial so that a red dot in the center is lined up with either red dots on either side of the “R”. Both red dots activate rewind mode. With the red dot somewhere in between the two, the film transports normally. The film door release is a little tricky in that you need to fold out a little handle and then give it a twist to release the lock. Finally, the tripod socket is off to the side, but due to the small size of the camera, having it centrally located in the middle likely won’t cause any problems.

Around back, there’s little to see other than the eyepiece opening for the viewfinder, and the back of the film advance lever. The entire rear door is covered in the same gray leatherette as the front.

The sides of the camera are symmetrical with nothing to see, not even strap lugs. This means that if you wanted to carry the camera around your neck, you’d need to either use the original case, or the type that screw into a tripod socket. Thankfully, the camera’s small size and light weight mean that it easily fits into a medium coat pocket or handbag.

The entire back and bottom of the camera slide off to reveal a very small film compartment. With a film gate that’s only 24mm wide, the camera doesn’t need to be as wide, but another space saving trick is that the supply side angles the cassette slightly towards the front helping to minimize the horizontal width of the camera. Film transports from left to right onto a fixed, plastic take up spool. The spool has two slots, but they are intended to be used together. Stick the leader in the larger slot indicated with a white dot and pass it through the other opening to secure it to the spool. For such a small camera, the take up spool is unusually large. Because of it’s increase diameter, this is the reason the Sketch cannot handle a 36 exposure cassette as there wouldn’t be enough room for the entire strip to wind around the spool. This was a curious choice, which I cannot find a logical reason for. Considering nearly every half frame 35mm camera allows for use of 36 exposure cassettes, I can’t quite explain it.

The Copal shutter on the Mamiya Sketch is thin, not sticking out too far behind the front of the camera. As a result the shutter speed and focus rings are rather narrow. In what I assume was an effort to save space, the aperture is controlled via a ring around the front face of the shutter. This likely was a wise decision as putting all three rings on a thin shutter like this would have further squished the controls together. Shutter speeds from 1 to 300 plus Bulb are available and the focus ring is marked from 0.6 meters to infinity with a single click stop at the 5 meter mark, to indicate a distance that maximizes depth of field for fast action group shots. Using the depth of field scale in the Sketch’s user manual, at f/8 and the lens focused to 5 meters, everything from 2.4 meters to Infinity will be in focus.

Considering the small size of the camera, the viewfinder is large enough to see all four edges while wearing prescription glasses. The image is bright and offers good contrast with a bluish green back and yellow frame lines and a square combined image rangefinder patch in the middle. It is hard to see in my viewfinder image to the right, but parallax correction marks are in the upper left corner to indicate the frame at close focus. There is no other information about exposure or other settings in the viewfinder.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the Mamiya Sketch, is that setting aside the historical significance of being the first and only Japanese 24mm x 24mm camera, everything else about it is pretty typical of cameras from it’s era. The rangefinder works the same, the film advance works the same, selecting f/stops and shutter speeds works the same, even loading film is the same (other than not being able to use a 36 exposure cassette).

That the Mamiya Sketch is sorta like other cameras, but smaller, and it shoots an image size not typical of Japanese cameras is it’s greatest strength. It’s basically like a 2/3rds 35mm rangefinder and for a 2/3rds rangefinder, it feels well made, has all the features you’d expect, and has a lens made by a company known for making good images. What’s there not to like? Keep reading…

My Results

I was pretty excited to shoot the Mamiya Sketch. This was a camera that before I bought it, I didn’t even know it existed. I’ve shot other square format 35mm cameras like the Berning Robot Junior and Photavit IV, but those both require special cassettes to load, and of the ones I shot, don’t have a rangefinder. The Sketch arrived in good condition and getting an itch to load in some of my all time favorite film, I quickly cut a strip of Kodak Panatomic-X into a reloadable cassette and took it out. The length of film I cut was approximately the length for 12 exposures of a full frame camera, but in the Sketch, I hoped to get around 20.

Rokkor, Hexanon, Nikkor, Takumar, these are all the names of lenses that before you see any images made from them, you know they’re going to be good. You might as well add “Sekor” to that list as Mamiya’s house brand of Sekor lenses are up there with other A-list Japanese lens companies.

I expected nice and sharp images with good contrast and little to no obvious imperfections when I took my trial roll from the tank, and that’s exactly what I got! Although I’ll admit that my usually reliable guess focusing abilities were not in top form while shooting the Sketch, most of the roll was in focus, with excellent sharpness corner to corner, excellent contrast, and only the slightest bit of vignetting near the corners.

Sadly, the camera started to give me some problems near the end of my first roll, so I didn’t shoot a second, but had I did, it would have likely been in color, and more than likely I would have gotten just as excellent color images with good color rendition and little to know chromatic aberrations, like is common with lesser lenses.

The compact size of the Sketch was a definite plus. This is a camera that easily fits into a small handbag or medium coat pocket. I’ve shot the Sketch’s nearest Japanese competitor the Pen, and the two cameras feel worlds apart. While the Pen is a nice camera capable of excellent images as well, with it’s plastic film advance wheel, scale focus operation, and limited feature set, you are constantly reminded it was an economic camera. The Sketch feels like a luxury item, with the same level of excellent build quality as the full size Mamiyas, just smaller. With it’s combined image coupled rangefinder, and traditional film advance lever, using the camera is just like full size Mamiyas, just smaller. And with it’s excellent Mamiya-Sekor lens, you get the same sharp images as the full size Mamiyas, just smaller.

Be far, the camera’s biggest miss is the the lack of strap lugs. When I received the Sketch, it did come with the original case and strap, but I’ve learned the hard way not to trust original leather straps from half century old cameras cases.

Shooting square format on 35mm film is a fun and unique experience, but I kind of get why it wasn’t more successful as there were several obstacles. For starters, composing a square image is a completely different experience from composing rectangular images. For many, the first time they look through the Sketch’s viewfinder, they might feel as though the sides have been cut off…which in a way, they have.

When shooting square images on medium format, like for example in a TLR, you have to make a decision whether you can fit your exposure “within the box” or whether you want to accept extra visual space above and below your image. Framing a rectangular image on a square TLR works because the increased size of the image still allows for a lot of detail in your image. With 35mm film, the 24mm x 24mm image has only 16% the area compared to a 60mm x 60mm image shot on 120 roll film. This requires you to use as much of the area as possible to retain detail in your image.

Even if you are successful with framing, developing has it’s challenges too. Photofinishers, especially those in the United States, hated developing film with half frame images as special care needed to be made to properly cut them, so asking them to accommodate square images likely would have been met with further resistance.

Assuming you had a knack for composing in a square frame and you developed images yourself and could handle a square frame, what would happen next? I am not aware of any slide mounts that were compatible with a 24mm x 24mm image and making negative prints would likely need to be done on custom paper as well. Perhaps you could crop the images to make them fit on rectangular paper, but doing that would result in a 18mm x 24mm image, which is exactly the same as half-frame.

Considering the Mamiya Sketch was released very nearly around the same time as the highly successful, Olympus Pen, photographers voted with their dollars, and the familiarity of a rectangular image, along with additional economy of twice as many images, allowed 18mm x 24mm “half frame” cameras to win.

Still, I do find it surprising that Mamiya gave up so quickly on it. The idea of a square format 35mm camera may have never caught on, but I can’t shake the feeling that the company didn’t try hard enough. It would have been interesting to see what a second Sketch model, or another square format 35mm camera might have looked like from other companies.

We’ll never know, but at least we do have this one example. By far, the most appealing attribute of the Sketch is it’s “one-off” history and rare combination of features and excellent build quality. Whether you’ve always been curious about what shooting 24mm x 24 images was like, or if you like rare cameras, or just want something different, I suspect the Mamiya Sketch will appeal to a great number of people. Unfortunately, if you’re a bargain hunter like me, that’s going to be a problem as when these cameras do show up for sale, they’re quite expensive. Still, if you happen to get a chance, you’re not likely going to get a second one, so this just might be the camera you open up your wallet for….a little wider!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

https://www.photo.net/forums/topic/329307-mamiya-sketch-how-to-open/

http://web.archive.org/web/20060218162713/http://www.kochi-med.net/moto/camera/sketch/sketch.htm (Archived)

http://fukucame.fan.coocan.jp/mamisketch.htm (in Japanese)

https://ameblo.jp/miyou55mane/entry-12777422668.html (in Japanese)

https://www.usedcameracameracamera.com/camera/mamiya-sketch/ (in Japanese)

https://yomocame.cocolog-nifty.com/blog/2013/03/post-a772.html (in Japanese)

I was drawn to this camera the first time I saw it…

Honestly, I would be concerned if you weren’t drawn to it! It is a special camera! 🙂

Mike, excellent post on a very interesting camera. I little more trivia on the Mamiya Sketch: factory records show that between January 1959 and June 1964, Mamiya produced 7,431 of these cameras. Not a large amount, but about the same quantity as some of the Mamiya Metra and Crown models.

Thank you for another interesting post about a camera I had never heard about!

I wonder if the microscope adapter can be a clue to the reason for the choice of the 24×24 mm format. As a microscope gives a round image, the square format is ideal for micro photography. Perhaps Mamiya tried to appeal to scientistes with the choice of format. They obviously didn’t succeed. Otherwise I totally agree with your thoughts about the 24×24 mm format. And I’m sure most consumers wanting to minimise their film budget would prefer 18×24 mm as cropping 24×24 to rectangular format would be wasteful.

Regarding slide frames, at least the popular (in Europe at least) GePe frames could be adjusted to square format by rotating one half 90 degrees.

When it comes to the lack of strap lugs which is an annoyance shared with a lot of cameras from the period, I think it must be understood that a quality camera was so expensive for most people at the time that most users wouldn’t dream of using it without the protection of the ever ready case.

Keep up the good work!

Thank you for an extensive and very interesting article. I have a Sketch myself and at present I am Hunting for a case for it. In the first picture in this article there is the Sketch with what appears to be a newly manufactured half case. Does anyone know where I can get one of these? Rgds Patrik

There’s another unique camera that shoots 24×24 images on 35mm film (respooled into Rapid-style brass cassettes): The Bolta Photavit. I just received a postwar model 4, with Prontor shutter, Radionar lens, both brass film cassettes, and the original case. This camera’s body is machined out of a block of aluminum – reminiscent of a tiny Clarus 35. The body is a tad smaller than a pack of cigarets. This little gem is next in line for a shutter CLA; I look forward to shooting it.

Excellent review of a camera that has a cult following in Japan and has become very expensive in the past 10 years. Wish I had bought one earlier. Wonder what the story is behind the camera that you found. The kind of camera that an adventurous and camera curious GI or tourist might have picked up in Japan in the late 1950s. I have read that the take up spool has trouble accepting a standard 36 exposure roll. Perhaps that is what gave you problems with your test? The shots you took are very sharp. Excellent find. Easy to see why people in Japan will pay a premium for this camera.

You are correct, a 36 exposure roll will not fit inside the Sketch. The diameter of the spool prohibits a length of film that long from wrapping around it. You could physically fit the cassette into the camera, but around the 40th exposure, it would start to bind up and eventually you wouldn’t be able to advance the film any longer. You’d probably also destroy the film by scratching it badly. If you are lucky enough to find one of these cameras, just stick with 24 exposure rolls of film.